To analyze the current state of knowledge regarding men's mourning experiences following the death of a loved one.

MethodAn integrative review was conducted using quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies published in English or Spanish between 2017 and 2022 that investigated men’s mourning experiences. Studies focused on grief in participants with different sexes or gender identities, maladaptive grief, persistent complex bereavement disorder, prolonged grief disorder, bereavement over pets, or losses other than a human death were excluded. Additionally, reviews, books, theses, editorials, and opinion pieces were not included. The search was conducted in CINAHL, PubMed, and Scopus in 2023. JBI tools were used for quality appraisal, and the analysis employed the constant comparative method.

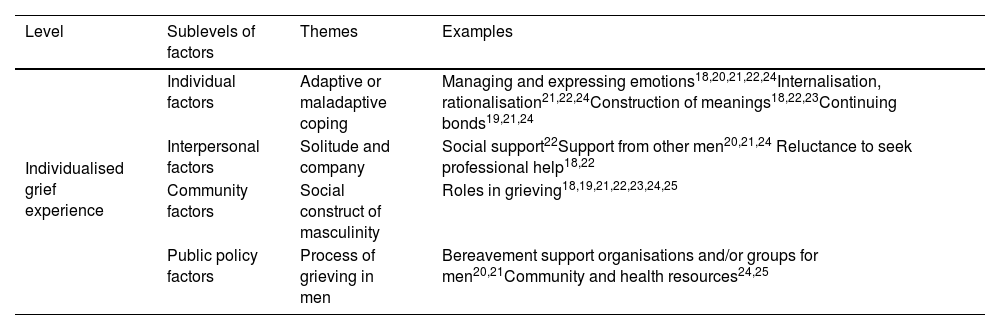

ResultsOur analysis of eight English-language documents with evidence levels IV-VI, informed by the Socioecological Model of Men’s Grief, revealed that factors at individual, interpersonal, community, and public policy sublevels interact significantly to shape men's grief experiences. Themes emerged along a continuum of intuitive and instrumental coping responses, including adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies, loneliness and social support needs, the influence of societal constructions of masculinity and the grieving process in men.

ConclusionsMen’s mourning experiences are complex and multifaceted, influenced by diverse expressions of masculinity and the interaction of various contextual factors. The Mental Health Nursing Process should prioritize understanding and addressing the unique experiences of bereaved men.

Analizar el estado actual del conocimiento sobre las experiencias de duelo en hombres por la muerte de un ser querido.

MétodoRevisión integrativa. Se incluyeron estudios cuantitativos, cualitativos y mixtos sobre las experiencias de duelo en hombres, en texto completo en inglés o español, del año 2017 al 2022. Se excluyeron revisiones, libros, tesis, editoriales y opiniones; investigaciones sobre el duelo que reclutaron participantes con: diferente sexo o identidad de género; duelo inadaptado, trastorno de duelo complejo persistente, trastorno de duelo prolongado; duelo por una mascota o pérdidas distintas a la muerte de una persona. La búsqueda se ejecutó en CINAHL, PudMed y Scopus durante el 2023. La evaluación se realizó con las herramientas de JBI. El análisis se elaboró con el método de comparación constante.

ResultadosLa muestra fue de 8 documentos escritos en inglés con niveles de evidencia entre IV y VI. Considerando el Modelo Socio-ecológico del Duelo en Hombres, las experiencias de duelo en hombres se conformaron por interacciones complejas entre subniveles de factores individuales, interpersonales, comunitarios y de políticas públicas, de los que se derivaron temas como afrontamiento adaptativo o desadaptativo, soledad y compañía, constructo social de la masculinidad y proceso de duelo en hombres, presentes en un continuum de respuestas de afrontamiento intuitivas e instrumentales.

ConclusionesLas experiencias de duelo en hombres son amplias, influenciadas por la multiplicidad de masculinidades y la interacción de distintos factores del contexto. El Proceso de Enfermería de Salud Mental debería centrarse en las vivencias del doliente.

Research on bereavement has focused on the study of women’s experiences and care, and there has been limited research on bereavement in men.

What does it contributeMen’s experiences of bereavement are diverse, and they should not be stigmatised according to traditional masculinity. The trajectories of grief encompass issues such as adaptive or maladaptive coping, solitude-company, construct of masculinity, and the grieving process in men.

Grief is a sensitive human response to a real, anticipated, or perceived significant loss that threatens the world of individual and/or group meanings. It has been argued that the central focus of grieving is the reconstruction of meanings through self-narratives in order to find sense, value, or personal development faced with the challenge of death. Narratives dynamically facilitate the understanding of the individual’s personal story where the self, the world, and others converge.1

Bereavement has natural and constructed components that make it an indiscriminate and specific life trajectory for each griever. It is a complex, self-limiting process that is woven into a continuum of interdependent coping strategies that attempt to adapt to the new reality of the death of a loved one, even though these strategies may be maladaptive. It includes physical, mental, socio-cultural, and spiritual manifestations that impact the lives of the bereaved.2

Men have been characterised within hegemonic or traditional masculinity, which refers to a gender standard that defines expected behaviour in a cultural context in terms of self-perception, relationships with other people, and the way they value life, expressing dominant, aggressive, violent, heterosexual behaviours, as well as other related characteristics such as masculinity and the anti-femininity mandate.3,4

Therefore, as a result of this social categorisation, they have adopted gender roles of being less expressive and more solitary in their experiences of bereavement (i.e., thoughts, feelings, doubts, interactions, expectations, and/or preferences). Furthermore, they have difficulties in seeking or accepting help, assuming that they are seen to be less affected than other people. In addition, the existing literature has focused on the study and care of bereavement in women, which raises questions as to its sensitivity to male forms of grief demonstration.5 Nevertheless, evidence shows that some men challenge and reject the conventional norms associated with hegemonic masculinity. These individuals have undergone a transformation, exhibiting traits perceived as feminine in their personal, professional, familial, and social roles. They demonstrate a proclivity for gender equality and espouse more progressive and feminist forms of masculinity.6 Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that there are a range of coping styles among bereaved men, from intuitive (emotion-focused) to instrumental (activity-focused), and vice versa.7 This would suggest that the experience of bereavement in men is not a fixed process.

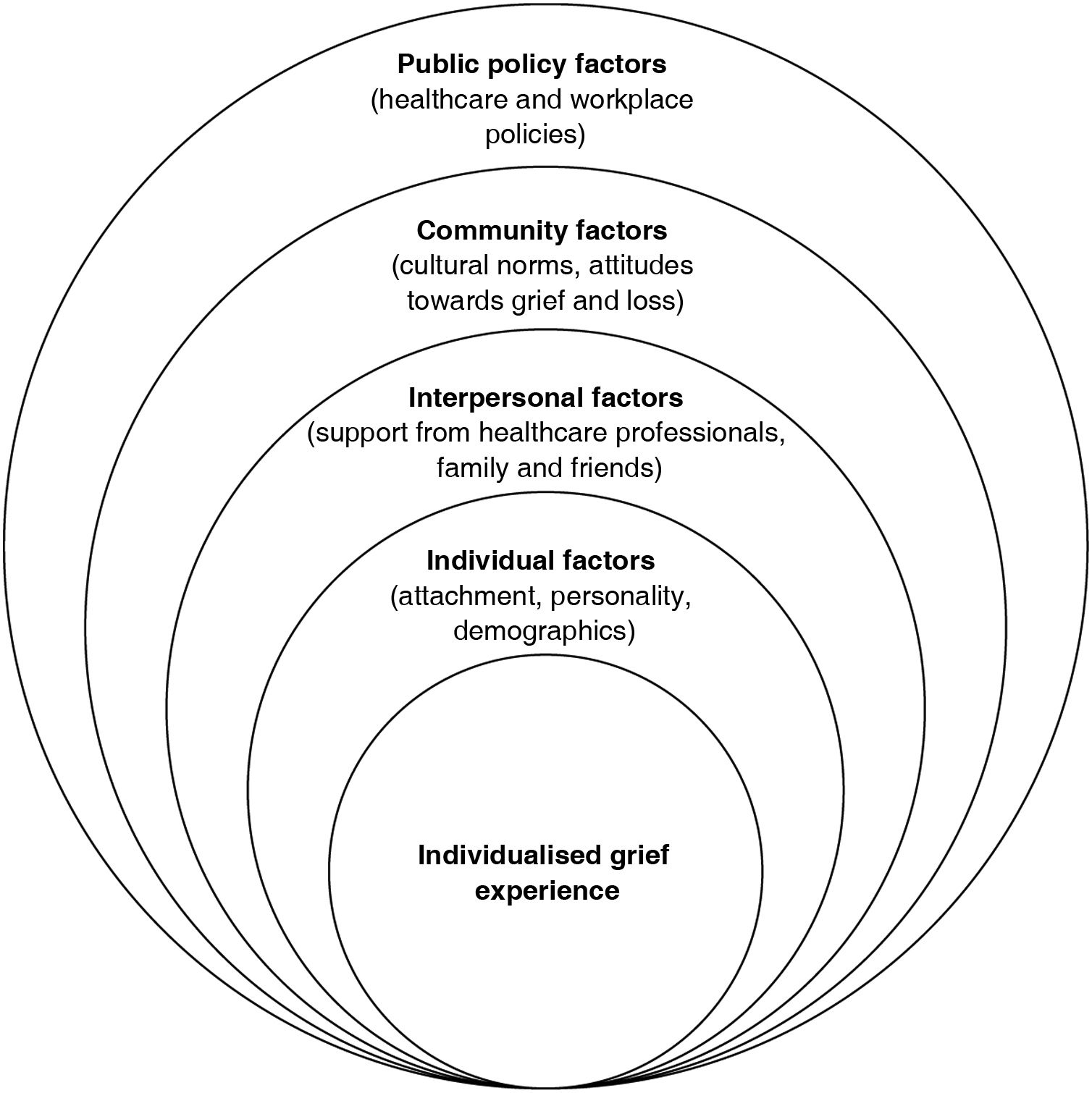

In light of the above considerations, it is imperative to study this issue in greater depth. To this end, the socio-ecological model of men’s grief has been proposed as a conceptual framework that aims to gain an understanding of this phenomenon in the context that it is not an isolated experience. This process is understood as a dynamic and intricate network of interactions that includes individual, interpersonal, community, and public policy levels7 (see Fig. 1).

Individual factors encompass aspects of personality, attachment, and socio-demographic characteristics. Interpersonal factors include perceived support from family, friends, and health professionals. Community factors pertain to cultural norms and attitudes towards grief and loss. Public policy factors emphasise health and workplace policies. Furthermore, the focus is on men who have experienced a significant loss and their attitudes towards it.7 The model would facilitate our comprehension of the non-linear nature of men’s narratives, which are shaped by the various factors that constitute their biography.

Although knowledge on the subject is limited, some previous secondary research has analysed men’s bereavement experiences, demonstrating that bereaved men are affected by loss in several areas of their lives to the same extent as other people, and need equality in grief support and recognition of their grief.8 It has also been suggested that their experience of grief is disenfranchised by behavioural norms that pigeonhole them into stereotypes of strength, and that they intellectualise or rationalise their grief,9 leading to its repression as the expression of grief is internalised as a reflection of the stoicism of traditional masculinity.10 It would be helpful to examine this issue in depth in order to promote greater sensitivity to it.

It is therefore in in the interest of mental health nurses to approach this distressing issue in order to gain a better understanding of it and to strengthen their evidence-based strategies through the mental health nursing process (MHNP). In this framework, their expertise in life-and-death scenarios enables them to maintain a close relationship in accompanying the bereaved.1 In particular, they implement a therapeutic process based on the interpersonal helping relationship, which is used to approach bereaved men. In this intervention, the griever discovers the meanings of the loss through nurse-person interaction, which provides comfort.11

In light of the above considerations, this integrative review (IR) aims to contribute to the discourse on bereavement in men, irrespective of the circumstances surrounding the death, including kinship, time elapsed, cause of death, and other factors. Through a synthesis of existing knowledge, the review seeks to enhance understanding and promote health and gender equity in this phenomenon, ensuring that all individuals have access to equitable services for bereavement management, while acknowledging the specific needs of different population groups. Consequently, mental health nurses and related professionals will be able to enhance their care practices for the betterment of men's health and their needs. Therefore, the objective is to analyze the current state of knowledge regarding men's mourning experiences following the death of a loved one.

MethodIn order to enhance the quality and transparency of this secondary research, we adhered to the guidelines set out in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement 2020 (PRISMA Statement 2020), which provide extensions for the reporting of reviews.12

An IR was conducted with the objective of synthesising recent scientific literature on men’s experiences of grief. The aim was to develop a comprehensive understanding and provide an overview of the phenomenon.13 To achieve this, a five-stage process was undertaken, comprising the following steps: 1. problem identification, 2. literature search, 3. data evaluation, 4. data analysis, and 5. presentation.14

The PICo strategy (Population = Men, Interest = Bereavement experiences, Context = Death of a loved one) was employed for the purpose of identifying problems, as it proved an efficacious approach to research, enabling the formulation of a question based on the proposed objective.13 The research question was formulated as follows: What are men’s mourning experiences following the death of a loved one? A researcher conducted a preliminary search in the PubMed database to check the main keywords used in the study of the problem theme.

The following inclusion criteria were defined for the literature search: full-text quantitative, qualitative, or mixed studies on bereavement experiences following the death of a loved one (apart from the situations that mediated it); specific participant population of people who identified as men; English or Spanish language; time span from 2017 to 2022 (this period was set to identify the most recent research). The exclusion criteria were set as follows: reviews, books, theses, dissertations, editorials, or opinions; bereavement research that recruited participants with different sex or gender identities; maladaptive grieving, persistent complex bereavement disorder, prolonged grief disorder; grief over a pet, or losses other than the death of a person.

In accordance with the research question and eligibility criteria, two researchers conducted an independent and simultaneous search strategy in literature databases CINAHL, PubMed, and Scopus during March and April 2023. Keywords (controlled vocabulary) from Descriptors in Health Sciences (DeCS) and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used. In English ‘men’, ‘grief’, ‘bereavement’, while in Spanish ‘hombres’, ‘pesar’, ‘aflicción’ were used.

The determined descriptors were linked using Boolean operators, 'AND' and 'OR', in order to create combinations such as: 1. ‘Men’ AND ‘Grief’ OR ‘Bereavement’, 2. “Hombres” AND “Pesar” OR “Aflicción”. Articles were considered where the relevant descriptors were present in the title, abstract, or keywords. The Mendeley reference manager was used to improve the organisation, selection, and elimination of duplicates.15 In addition, another researcher manually searched the references of the included studies for relevant research, however, no publications were added using this strategy. Any discrepancies were resolved by the researchers in group discussions.

Three researchers independently assessed the data. One researcher assessed eligibility and excluded papers that did not meet the defined characteristics, while two researchers read the studies and assessed their quality and relevance to the study phenomenon. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

For each study, the critical appraisal tools proposed by JBI16 were used, which include a checklist with answers of yes, no, unclear, not applicable. A hierarchy was used to determine the level of evidence, from level I systematic reviews or meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials to level VII expert opinion.17 All selected articles were assessed with caution.

The data were analysed using the constant comparison method,14 which involves reduction, visualisation, and comparison of data, drawing conclusions and verification. Reduction involved one researcher dividing the articles into subgroups according to the methodology used. The data were extracted by two independent researchers using the data extraction tool proposed by JBI16 to summarise and organise the data, resulting in a matrix containing author, title, journal, year, volume, number, pages, study design, country, context, time period of data collection, participant characteristics, measurement methods, and main findings.

Visualisation was therefore provided as a starting point for data interpretation. An iterative process guided the comparison of data to identify themes that were grouped together. These stages were developed taking into account the socio-ecological model of men’s grief.7 The elaboration of conclusions was then revised to include as much data as possible, which were checked with primary sources for accuracy and confirmation. The three researchers debated and resolved disagreements to reach a final decision, thus answering the research question through a synthesis of conclusions.

Finally, conclusions and implications for practice and research were presented. The IR was guided by good practice guidelines for secondary research. At all times, the authorship and ideas of the included publications from indexed scientific journals were respected.

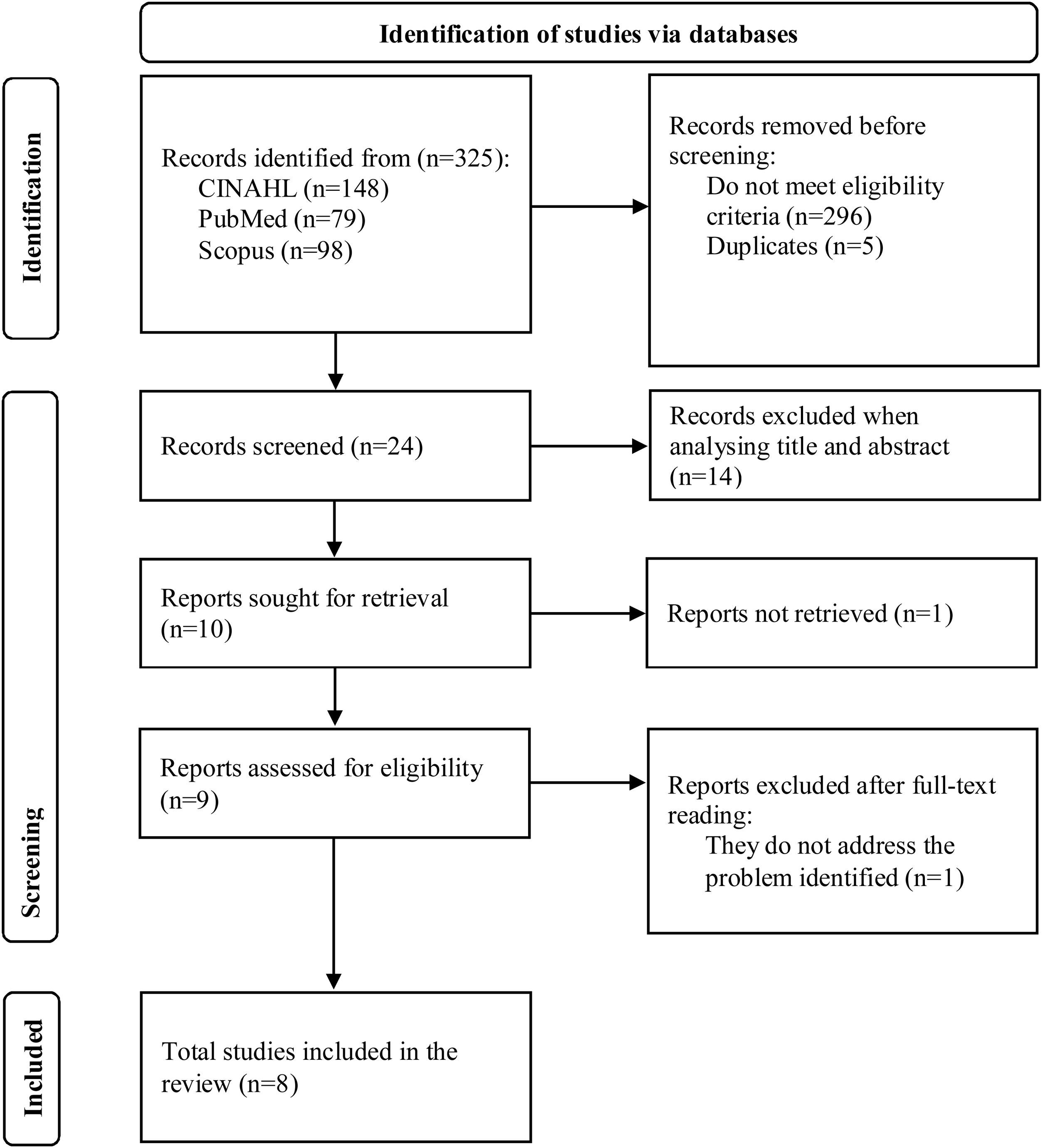

ResultsThe literature search yielded 325 papers. The results were filtered according to the eligibility criteria, duplicates were removed and the title and abstract of each citation were analysed. Twenty-four articles were retained and screened to determine if they addressed the problem identified. Consequently, the final sample consisted of 8 included publications (n = 8; see Fig. 2).

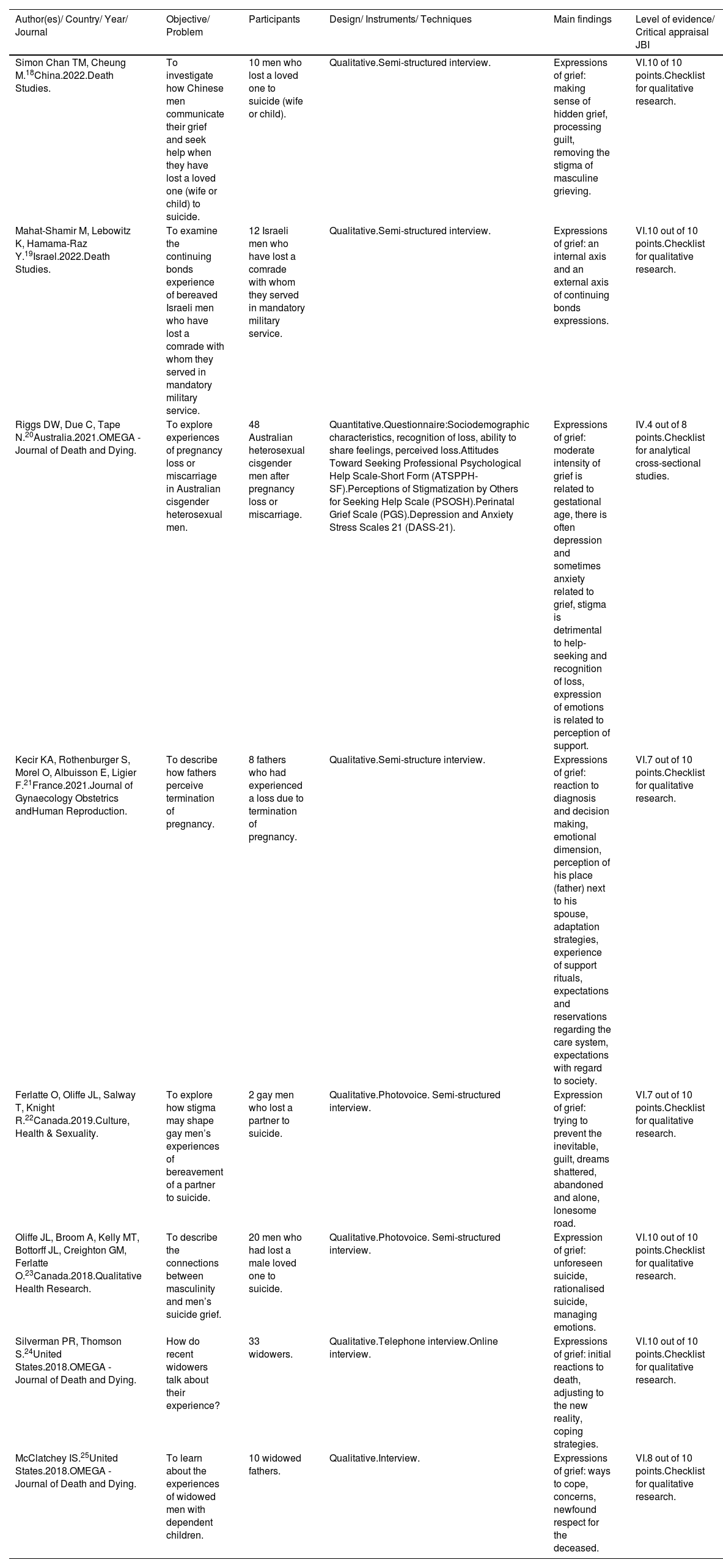

The included publications were retrieved from CINAHL, 37.50% (n = 3), 25.00% from PubMed (n = 2), and 37.50% from Scopus (n = 3). One hundred percent (n = 8) were written in English. Men’s grief was examined in 37.50% due to suicide (n = 3), in 25.00% due to widowerhood (n = 2), in 25.00% due to perinatal death (n = 2), and in 12.50% due to military death (n = 1). Other characteristics of the studies are shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included.

| Author(es)/ Country/ Year/ Journal | Objective/ Problem | Participants | Design/ Instruments/ Techniques | Main findings | Level of evidence/ Critical appraisal JBI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simon Chan TM, Cheung M.18China.2022.Death Studies. | To investigate how Chinese men communicate their grief and seek help when they have lost a loved one (wife or child) to suicide. | 10 men who lost a loved one to suicide (wife or child). | Qualitative.Semi-structured interview. | Expressions of grief: making sense of hidden grief, processing guilt, removing the stigma of masculine grieving. | VI.10 of 10 points.Checklist for qualitative research. |

| Mahat-Shamir M, Lebowitz K, Hamama-Raz Y.19Israel.2022.Death Studies. | To examine the continuing bonds experience of bereaved Israeli men who have lost a comrade with whom they served in mandatory military service. | 12 Israeli men who have lost a comrade with whom they served in mandatory military service. | Qualitative.Semi-structured interview. | Expressions of grief: an internal axis and an external axis of continuing bonds expressions. | VI.10 out of 10 points.Checklist for qualitative research. |

| Riggs DW, Due C, Tape N.20Australia.2021.OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying. | To explore experiences of pregnancy loss or miscarriage in Australian cisgender heterosexual men. | 48 Australian heterosexual cisgender men after pregnancy loss or miscarriage. | Quantitative.Questionnaire:Sociodemographic characteristics, recognition of loss, ability to share feelings, perceived loss.Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale-Short Form (ATSPPH-SF).Perceptions of Stigmatization by Others for Seeking Help Scale (PSOSH).Perinatal Grief Scale (PGS).Depression and Anxiety Stress Scales 21 (DASS-21). | Expressions of grief: moderate intensity of grief is related to gestational age, there is often depression and sometimes anxiety related to grief, stigma is detrimental to help-seeking and recognition of loss, expression of emotions is related to perception of support. | IV.4 out of 8 points.Checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies. |

| Kecir KA, Rothenburger S, Morel O, Albuisson E, Ligier F.21France.2021.Journal of Gynaecology Obstetrics andHuman Reproduction. | To describe how fathers perceive termination of pregnancy. | 8 fathers who had experienced a loss due to termination of pregnancy. | Qualitative.Semi-structure interview. | Expressions of grief: reaction to diagnosis and decision making, emotional dimension, perception of his place (father) next to his spouse, adaptation strategies, experience of support rituals, expectations and reservations regarding the care system, expectations with regard to society. | VI.7 out of 10 points.Checklist for qualitative research. |

| Ferlatte O, Oliffe JL, Salway T, Knight R.22Canada.2019.Culture, Health & Sexuality. | To explore how stigma may shape gay men’s experiences of bereavement of a partner to suicide. | 2 gay men who lost a partner to suicide. | Qualitative.Photovoice. Semi-structured interview. | Expression of grief: trying to prevent the inevitable, guilt, dreams shattered, abandoned and alone, lonesome road. | VI.7 out of 10 points.Checklist for qualitative research. |

| Oliffe JL, Broom A, Kelly MT, Bottorff JL, Creighton GM, Ferlatte O.23Canada.2018.Qualitative Health Research. | To describe the connections between masculinity and men’s suicide grief. | 20 men who had lost a male loved one to suicide. | Qualitative.Photovoice. Semi-structured interview. | Expression of grief: unforeseen suicide, rationalised suicide, managing emotions. | VI.10 out of 10 points.Checklist for qualitative research. |

| Silverman PR, Thomson S.24United States.2018.OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying. | How do recent widowers talk about their experience? | 33 widowers. | Qualitative.Telephone interview.Online interview. | Expressions of grief: initial reactions to death, adjusting to the new reality, coping strategies. | VI.10 out of 10 points.Checklist for qualitative research. |

| McClatchey IS.25United States.2018.OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying. | To learn about the experiences of widowed men with dependent children. | 10 widowed fathers. | Qualitative.Interview. | Expressions of grief: ways to cope, concerns, newfound respect for the deceased. | VI.8 out of 10 points.Checklist for qualitative research. |

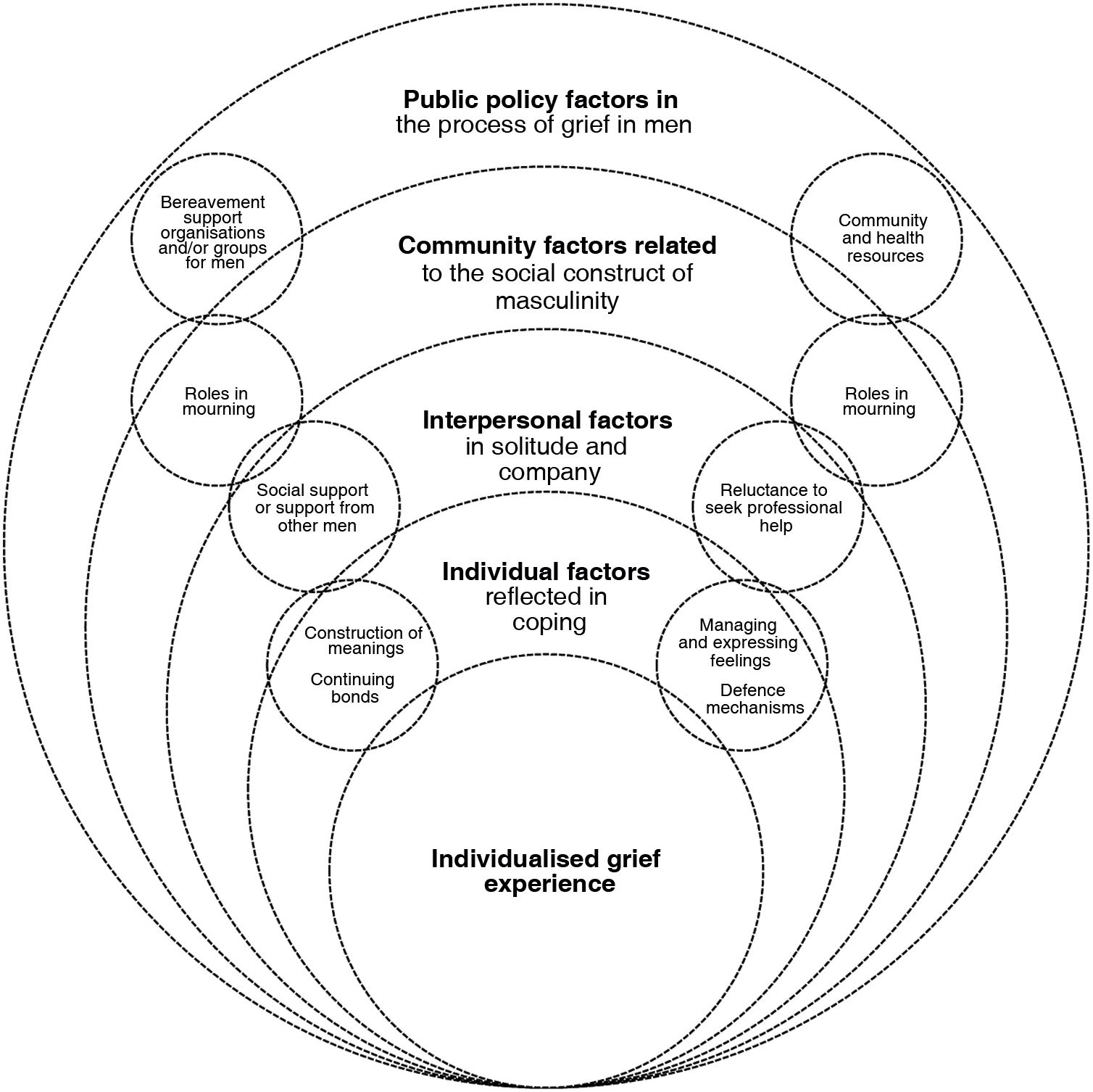

The themes identified were grouped according to the four sub-levels of factors proposed by the socioecological model of men's grief. It is important to note that the sub-levels are not static, but have a bidirectional dynamism, so that the themes are interdependent; there is a constant influence of factors in the process of men’s grief.9 The synthesis of the conclusions is presented in Table 2.

Synthesis of men’s experiences of bereavement after the death of a loved one.

| Level | Sublevels of factors | Themes | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individualised grief experience | Individual factors | Adaptive or maladaptive coping | Managing and expressing emotions18,20,21,22,24Internalisation, rationalisation21,22,24Construction of meanings18,22,23Continuing bonds19,21,24 |

| Interpersonal factors | Solitude and company | Social support22Support from other men20,21,24 Reluctance to seek professional help18,22 | |

| Community factors | Social construct of masculinity | Roles in grieving18,19,21,22,23,24,25 | |

| Public policy factors | Process of grieving in men | Bereavement support organisations and/or groups for men20,21Community and health resources24,25 |

Individual factors were highlighted by coping experiences (adaptive or maladaptive), such as experiencing feelings of guilt, fear, being judged, incomprehension18,21,22,24; expressing or not expressing feelings18,21,22; experiencing depression or anxiety20; spending time on other activities21,22,24; making sense of the loss, learning, and personal development18,22,23; maintaining a connection with the deceased by transforming the relationship through feeling their presence, imitating their characteristics, or participating in memorials.19,21,24

Interpersonal factorsInterpersonal factors describe the ambivalence of solitude and company. On the one hand, coping with the loss alone,22 hesitating to accept any kind of help,18,22 or cutting off relationships with other people.24 On the other hand, increasing perceived support (family, friends), and seeking help from professionals or other men.18,20,21,22,24

Community factorsThe above was mediated by community factors related to the social construct of masculinity, such as being strong, suppressing the experience of pain, or protecting the family.18,19,21,22,23,25 However, they also elicited less stereotypical attitudes such as showing more empathy, ease in expressing thoughts and feelings (verbally or non-verbally), and a commitment to revitalising relationships with others.18,22,24

Public policy factorsFinally, public policy factors highlight men's need for recognition, care, and protection in the face of significant loss20,21; including participation in bereavement support organisations specifically for men, and access to community and health services such as childcare assistance, financial support, therapy, or medication.24,25

A diagram reflecting the synthesis of evidence is shown in Fig. 3.

The above figure shows a mind map illustrating the findings on men’s experiences of grief following the death of a loved one. The central level is the individual experience of grief, indicating that it is a shared process, with sub-levels of individual, interpersonal, community, and public policy factors. For each factor, themes and examples identified in the data analysis are given. The mind map represents an open system symbolising the complexity of interactions in the socio-ecological model of men’s grief.

DiscussionA deeper understanding of the findings presented here would suggest that men’s experiences of grief following the death of a loved one are varied. In some cases, they are influenced by gender norms and expectations associated with hegemonic masculinity, but in other cases they demonstrate changes in traits of traditional masculinity, such as taking on self-care roles in expressing feelings or seeking support, revealing more progressive masculinities.

In this sense, the socio-ecological model of men’s grief allows an approach to this phenomenon by proposing sub-levels of factors that interact bidirectionally, demonstrating the dynamism that arises in the face of a significant loss and the transcendence of the environment. In the synthesis of conclusions, the analysis reveals themes of adaptive or maladaptive coping in the individual factors, solitude and company in the interpersonal factors, the social construct of masculinity in the community factors, and the process of men’s grief in the public policy factors, which are closely interrelated.

Ultimately, the death of a loved one is a painful event that causes suffering for all people without discrimination and can affect them for the rest of their lives. Each individual’s experience is highlighted as unique, as a significant loss confronts the meanings of one’s own story, embedded in a changing socio-cultural environment, leading to a wide range of coping responses and needs to be met.26

Thus, the individual experience of bereavement of men would be different in style from that of others who do not identify as male and would be purely subjective. Therefore, in the midst of questioning the appropriateness of traditional ideals of masculinity and private or hidden expressions for coping with grief, the idea of male, female, or other forms of grief should be debated in order to reduce social stigma, focus the validation of grief on the individual and increase sensitivity to the real needs that deserve to be addressed,27 without neglecting the impact of environment on such experience.

Thus, the sublevel of individual factors is an intimate space in men’s grief, which would have a more private than public masculine character. Emptiness prevails; therefore, feelings are disclosed in solitude, characterising grievers as stoic. However, this masculinity could be undermined by preventing grievers from conforming to such archetypes by showing a more forgiving attitude towards themselves and their feelings.28

Taking these considerations into account, men's experiences are forced to respond creatively, internally and externally, based on meanings rather than their sex or gender identity.29 The findings reflect how men may adapt their experiences of grief to public spaces, by engaging in activities for personal development, or to private spaces, by maintaining an internal relationship with the deceased loved one in order to seek comfort according to their needs.

In the sub-level of interpersonal factors, the influence of the environment on traditional behaviour highlights men’s suspicion of revealing their private lives to others. Subjection to the disadvantages of grief due to lack of recognition would prevent help-seeking, compounded by difficulties in admitting it due to poor communication with social connections such as family members or health personnel.30

However, grief would allow for a heartfelt connection with other people, from which men are not exempt, with the possibility of being comforted by family, friends, or professionals in the hope that everything will improve.31 The results show the weight of hegemonic masculinity in some who experience the loss alone, although others face the vicissitudes with greater openness to strengthening social support.

With regard to the sub-level of community factors, the construct of masculinity is sometimes contrasted due to the link with the cultural context in which it develops.32 In this context, it has been mentioned that this construct moves from the emotionally stoic to the expressive in the midst of men’s struggle against oppression and desire for more connection with themselves and others. It is therefore understood that there is a multiplicity of masculinities where the regulation of attitudes imposed by hegemonic masculinity is no longer the only social rule, but where strength and emotional intelligence are established as contemporary values for the new masculinities.33

Finally, the sub-level of public policy factors should develop a model that makes men's grief visible in order to give them a voice and prevent them from being vulnerable to maladaptive grieving. Through a combination of actions, grief after loss would be given attention and validated without going unnoticed.34 There is a need for community resources to remove barriers to accessing support for individual, family, and community wellbeing in adjusting to grief.30 This would fill the gaps of recognition, care, and protection in men’s process of grieving.

Consequently, the environment generates a pattern in the reactions of grievers that justifies the heterogeneity of the experiences encountered, which are permeated by individual biography and culture, in which symbolisms of identities associated with prevailing or emerging masculinities emerge, which define men’s responses to loss.

The strengths of this study are that it is one of the first to analyse men's bereavement experiences based on specific research on men's grief, giving it greater specificity. The involvement of specialist mental health and death and bereavement nurses also adds to the rigour of the review.

In terms of limitations, the results do not reflect all the available evidence on this theme due to limitations in the literature search strategy, access to information, and the fact that all documents are in English, excluding others in different languages that may be relevant. In addition, only some types of grief and some masculinities and cultures of the world are represented. It would therefore be inappropriate to generalise the findings of this IR.

In conclusion, men’s experiences of bereavement are diverse, as are masculinities. They manifest themselves in different ways along a continuum of responses that is influenced by a number of sub-levels of factors in which adaptive or maladaptive coping, solitude and company, the social construct of masculinity, and the process of men’s grieving interact. The death of a loved one, therefore, is not an isolated event for grievers, but depends on the elements present in a given context.

As recommendations for practice for mental health nurses and allied professionals, it is important to undertake a professional update to gain new knowledge and new evidence-based skills for individual and/or group bereavement support for men. Specifically, mental health nurses should base their intervention on the MHNP, which should be implemented in a framework of trust that favours the telling of each story, with the aim of understanding men’s experiences of grief. Finally, the development of evidence-based policies, plans, or programmes on bereavement in men and their need for destigmatisation, recognition, and support to promote their wellbeing is paramount.

Recommendations for research focus on unpacking masculinities and grieving styles. New studies should consider groups of grievers facing significant loss with different socio-demographic, cultural, spiritual, and circumstantial circumstances surrounding the death. The evidence generated should provide guidance on the best strategies to improve men’s quality of life.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.