The incidence of oncology patients is increasing due to the ageing of the population and advances in research leading to early diagnoses. This has resulted in an increase in the care required for patients at all stages of their illness. To describe the current situation of the overload of informal caregivers of cancer patients with tumour asthenia belonging to the Medical Oncology Service of the University Health Care Complex of Salamanca and the Palliative Care Unit of the Hospital de los Montalvos, we employed the following.

MethodsThis is a cross-sectional descriptive observational study conducted at the Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca and the Palliative Care Unit of the Hospital de los Montalvos from February to May 2023. The study involved 75 informal caregivers of oncology patients with tumour asthenia. Data was collected through interviews, which included sociodemographic information and measurement scales. The study employed the Barthel Scale, PERFORM questionnaire, and Reduced Zarit Caregiver Overload Scale to assess the informal caregivers' ability to care for cancer patients with tumour asthenia.

ResultsOf the caregivers, 58.7% were female, and the mean age was 60.0 years (±14.10). Over half (50.7%) of the caregivers experienced high levels of overload, making it impossible to care for the patient. Among patients with tumour asthenia, 37.3% were totally dependent, and 8.0% were moderately dependent. Of these caregivers, 58.7% had no prior caregiving experience, 80.7% had no training, and 77.3% never received help in caring for the patient.

ConclusionsIn the Medical Oncology service of the Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca (CAUSA) and the Palliative Care Unit of the Hospital de los Montalvos, over one third of caregivers of oncology patients with tumour asthenia experienced caregiver overload. Variables such as the patient's age, the caregiver's age, the number of care hours, and the willingness to seek help can influence the perception of overload. This can worsen the effective care of the patient. It is important to consider these factors when providing care.

En la actualidad, los cuidados de pacientes oncológicos, en cualquiera de las fases de su enfermedad, se encuentran en aumento debido a la incidencia de la propia enfermedad causada por el creciente aumento del envejecimiento de la población y por el aumento de nuevos diagnósticos oncológicos tempranos debido a los avances en investigación. Es por ello, por lo que queremos describir la situación actual de la sobrecarga de los cuidadores informales de pacientes oncológicos con astenia tumoral pertenecientes al servicio de Oncología Médica del Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca y la Unidad de Cuidados Paliativos del Hospital de los Montalvos.

MétodoEstudio observacional de tipo descriptivo transversal realizado en el Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca y la Unidad de Cuidados Paliativos del Hospital de los Montalvos desde el mes de febrero hasta el mes de mayo de 2023, con un total de 75 cuidadores informales de pacientes oncológicos con astenia tumoral. La recopilación de los datos se realizó mediante una entrevista; dónde se recogieron datos sociodemográficos y las siguientes escalas de medida: Escala Barthel, cuestionario PERFORM y Escala de Sobrecarga del cuidador de Zarit reducida.

ResultadosEl 58,7% de los cuidadores fueron mujeres siendo la media de edad de todos los cuidadores informales de 60.0 años (±14.10). Un 50,7% de los cuidadores informales experimentaron altos niveles de sobrecarga imposibilitando el cuidado del paciente oncológico con astenia tumoral causando claudicación familiar. El 37,3% de los pacientes con astenia tumoral presentaron dependencia total, el 8,0% dependencia moderada. El 58,7% de los cuidadores no tenían experiencia en el cuidado, el 80,7% no tenían formación y el 77,3% nunca recibieron ayuda en el cuidado del paciente.

ConclusionesLa sobrecarga del cuidador en pacientes oncológicos con astenia tumoral estuvo presente en más de un tercio de los cuidadores de pacientes del servicio de Oncología Médica del Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca (CAUSA) y la Unidad de Cuidados Paliativos del Hospital de los Montalvos. Existen variables que influyen en la percepción de dicha sobrecarga como son la edad del paciente, la edad del cuidador principal, el número de horas de cuidado o la predisposición a pedir ayuda agravándose más si cabe dicha sobrecarga y por ende el cuidado efectivo del paciente enfermo.

The care of cancer patients is increasing, it is important to understand the needs and factors involved in this care.

What it contributesKnowledge on the current situation of caregiver overload, which will allow an integral perspective, led by nurses, of the intervention needs to improve the level of overload of informal caregivers and achieve the best care for this type of complex patient.

Care for cancer patients at any stage of their disease is currently increasingly required due to the incidence of the disease itself, ageing of the population, and the number of new early oncological diagnoses due to advances in research.1–3

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is a syndrome that encompasses the physical and mental fatigue experienced by an oncology patient at all stages of their disease, resulting in, among other things, weakness, malaise, or need for rest.4

The care of the cancer patient with cancer-related fatigue concerns many multidisciplinary teams, involving the need to support the patient on a day-to-day basis as they progress through their disease.5 It is essential for the whole community that their activities of daily living (ADLs) are attended to, which includes the need to have a person close by, an informal caregiver, to attend to the patient's needs and provide the necessary help with any tasks that the patient cannot do independently.6 Informal care is a form of unpaid care provided to people or patients with some form of physical or mental dependence by family members or other persons, without any bond of union or obligation, helping with various personal, work, or domestic needs, managing finances, organising external services, and even supporting and accompanying them to consultations.7

Informal care can be provided by those around the patient: relatives, neighbours, friends; formal care that involves payment, such as professional care or even volunteering, is excluded. Effective care means knowing the different specific needs of the patient and how to meet them. This kind of knowledge and attitude on the part of the caregiver can lead to significant overload due to a lack of experience, which affects the caregiver biologically, psychologically, and socially.6

Main caregiver overload may be influenced by different factors such as the age of the patient, the stage of the disease, the age of the informal caregiver and their gender, the culture of care, the socioeconomic level of the family unit or the relationship with the cared-for person, among others.8–13

On this basis, we hypothesise that cancer-related fatigue may produce physical and psychosocial needs in many patients during the process of their illness, which may lead to overload of the informal caregiver.

The main aim of the present study, therefore, was to describe the current situation of overload in informal caregivers of cancer patients with cancer-related fatigue using the Zarit Reduced Caregiver Overload scale at the time of hospital admission.

MethodDesign: Observational cross-sectional descriptive study, following the STROBE guidelines (Supplementary material).

Population and study setting: Participants were recruited between February and May 2023 in the Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca (CAUSA) and the Palliative Care Unit of the Hospital de los Montalvos, Salamanca.

Sample selection criteriaInclusion criteria: caregiver over 18 years of age, not contracted for caregiving or with specific health training, being an informal caregiver of a cancer patient admitted to the CAUSA or the palliative care unit of the Montalvos hospital, agreeing to participate in the study and signing the informed consent form.

Exclusion criteria: caregiver under 18 years of age, not being able to understand the questions in the questionnaire, not being fluent in Spanish.

Withdrawal criteria: failure to complete all the assessment tests.

Sample size: Convenience sampling was used for the selection of participants, i.e., the sample size was determined by the interviews conducted between February and May 2023 with caregivers of patients admitted to the Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca and the Palliative Care Unit of the Hospital de los Montalvos. All patients and caregivers who wished to participate in the study and who met the selection criteria were selected. The sample chosen was agreed from the scientific literature of similar studies by Alzehr et al.20 with a sample of 62 family caregivers and by Tripodoro et al.21 with a sample of 95 caregivers of cancer patients.

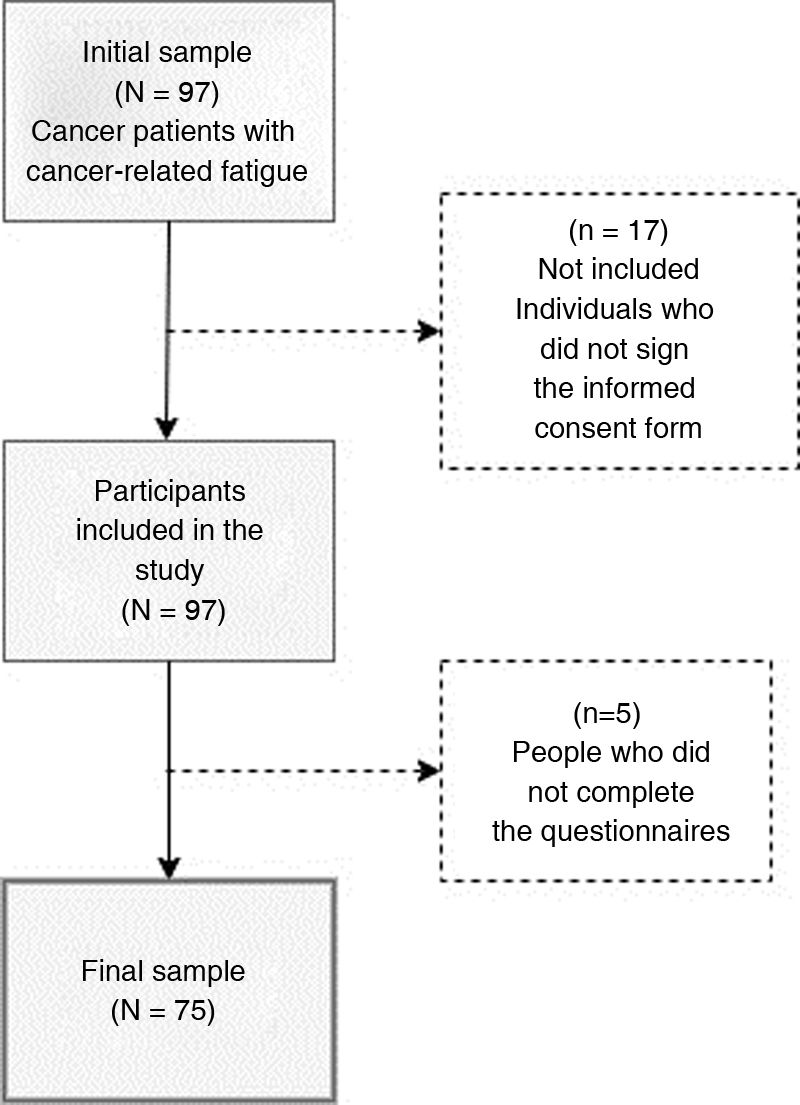

Recruitment: All patients and relatives admitted to the two services in the estimated period and who met the selection criteria were considered for recruitment; those who did not meet these criteria were excluded. A sample of 75 participants was obtained. Details of the sampling procedure are given in Fig. 1.

The variables to be studied: We must make a distinction in the study of variables, as the same variables were used for patient and caregiver.

The variables considered for the cancer patient with care-related fatigue were level of dependence, level of care-related fatigue, age, gender, type of anatomopathological diagnosis of cancer, and months since the anatomopathological diagnosis of cancer.

The variables considered for the informal caregiver of the cancer patient with cancer-related fatigue were: age, gender, relationship with the patient, previous experience in caregiving, area of residence, number of cohabitants, number of hours dedicated to caregiving, time spent as a caregiver, training in caregiving, and information about their own health as a caregiver.

A self-administered scale was used to obtain the data, completed with the healthcare staff, along with a clinical interview. The following measurement instruments were used:

- -

The Barthel Index:

The Barthel Index is a generic measurement that assesses level of independence with respect to the performance of activities of daily living (ADLs). In terms of its psychometric properties, we can add that it has good inter-observer reliability (Kappa indices between 0.47 and 1.00), good intra-observer reliability (Kappa indices between 0.84 and .97), and adequate levels of internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha of .86–.92). It can be interpreted as follows: 20–35 points: severe dependence; ≥60 points: slight dependence; 40–55 points: moderate dependence; 100 points: total independence.14

- -

PERFORM questionnaire:

The PERFORM questionnaire is an instrument developed and fully validated in Spain to assess cancer-related fatigue. In terms of its psychometric properties, we can add that it has an internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha (CA)). Overall CA = .94. CA of the dimensions: between 0.80 and .90. Test-retest reliability (Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC)). Overall ICC = .83. ICC of the dimensions: between 0.76 and .84. In terms of its interpretation, it states that the higher the score, the lower the cancer-related fatigue, however, the items represent three distinct dimensions. The dimensions measured by the questionnaire are “activities of daily living”, “beliefs and attitudes”, and “physical limitations”.15

- -

Reduced Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview:

This is a reduced version of the Zarit Interview produced by Gort A. et al. in 2005. In terms of its properties, it has a sensitivity between 36.84 and 81.58%, a specificity between 95.99 and 100%, a positive predictive value between 71.05 and 100%, and negative predictive values between 91.64 and 97.42%. In terms of interpretation, this scale is made up of 7 items scored on a Likert-type scale from 0 to 5. Scores above 17 can be obtained, indicating family claudication.16

In addition, we used a socio-demographic information questionnaire designed specifically for the study, providing information about the lifestyle of the patient and caregiver, as well as the style of care, which in one way or another influences the perception of overload.

Data collection: The study was conducted face-to-face by the investigator through an interview with each of the participating informal caregivers.

At the outset of the study, participants were given an information sheet explaining the nature of the present study, that there would be no negative consequences for not participating, and that the data would be handled appropriately. In addition, all participants were given the informed consent form to complete and sign if they wished to participate in the study.

Statistical analysis: At a descriptive level, the quantitative variables resulting from each of the questionnaires were analysed using the mean, standard deviation, maximum, minimum, frequency, and percentages.

The study variables were analysed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to determine whether they followed a normal distribution in each case. This allowed us to decide on the most appropriate statistical approach: parametric (for normal variables) or non-parametric (for non-normal or ordinal variables). As the variables did not follow a normal distribution, the non-parametric route was followed. The following statistics were defined:

- -

Spearman's correlation: used to determine whether there is a linear relationship between two ordinal variables and to study that this relationship is not due to chance; that is, that it is statistically significant.

- -

Mann-Whitney U-test: used to compare whether the mean scores of an independent variable (qualitative or quantitative) and a dependent variable (qualitative or quantitative) assume that differences in the mean score of the dependent variable are caused by the independent variable.

- -

χ2 test: used to examine differences between categorical variables in the same population, and thus to interpret the relationship between these two categorical variables. Values of p < .05 are considered significant.

We used SPSS Statistics version 26.0.0.2 for the entire analysis.

Ethical considerations: The study was conducted with the approval of the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Salamanca Health Area (reference code PI 2023 02 1213), whose favourable opinion is attached as Annex I. Furthermore, the study was conducted with the prior informed consent of the study subjects and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The participants were informed of the objectives of the investigation and of the risks and benefits of the research to be undertaken, (informed consent). Furthermore, the confidentiality of the subjects included was guaranteed at all times in accordance with the provisions of Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December, on Personal Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights and Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on Data Protection (GDPR). In accordance with Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on Data Protection (GDPR) and under the conditions set out in Law 14/2007 on biomedical research.

ResultsThe study had a sample of 80 patients with caregiver fatigue and their main caregivers, of which 5 were excluded during the process for failing to complete all the assessment tests, leaving a final sample for analysis n = 75.

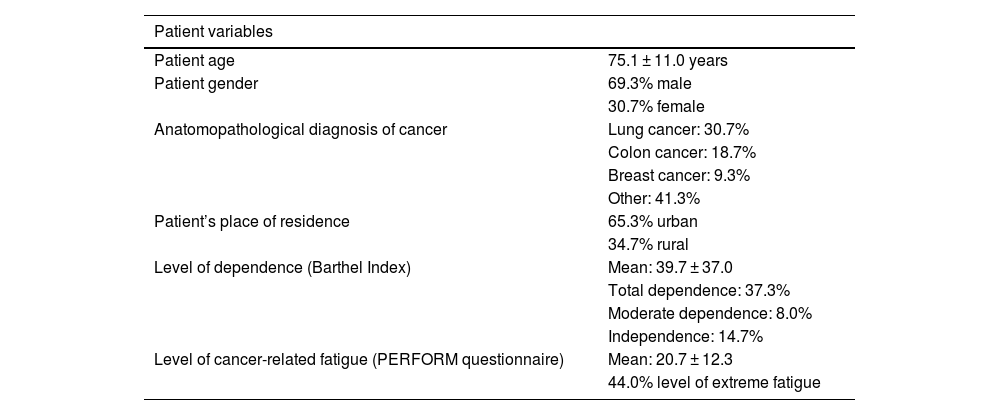

The mean age of the cancer patient was 75.1 years (± 11.1). There was no balance in the gender distribution of the patient, 69.3% men, and 30.7% women. There was also no equal distribution in location, 65.3% were in an urban setting, and 34.7% in a rural area. Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the patients evaluated.

Sociodemographic characteristics of patients with cancer-related fatigue.

| Patient variables | |

|---|---|

| Patient age | 75.1 ± 11.0 years |

| Patient gender | 69.3% male |

| 30.7% female | |

| Anatomopathological diagnosis of cancer | Lung cancer: 30.7% |

| Colon cancer: 18.7% | |

| Breast cancer: 9.3% | |

| Other: 41.3% | |

| Patient’s place of residence | 65.3% urban |

| 34.7% rural | |

| Level of dependence (Barthel Index) | Mean: 39.7 ± 37.0 |

| Total dependence: 37.3% | |

| Moderate dependence: 8.0% | |

| Independence: 14.7% | |

| Level of cancer-related fatigue (PERFORM questionnaire) | Mean: 20.7 ± 12.3 |

| 44.0% level of extreme fatigue | |

The most prevalent form of cancer was lung cancer (30.7%). The time since diagnosis in months had the following distribution: 30.7% were diagnosed less than half a year ago, 28% less than one year ago, while 12.7% were diagnosed more than 6 years ago. In terms of the number of lines of treatment used, the distribution was as follows: 21.3% of patients were not able to be given any line of treatment, while 29.3% received two or more lines.

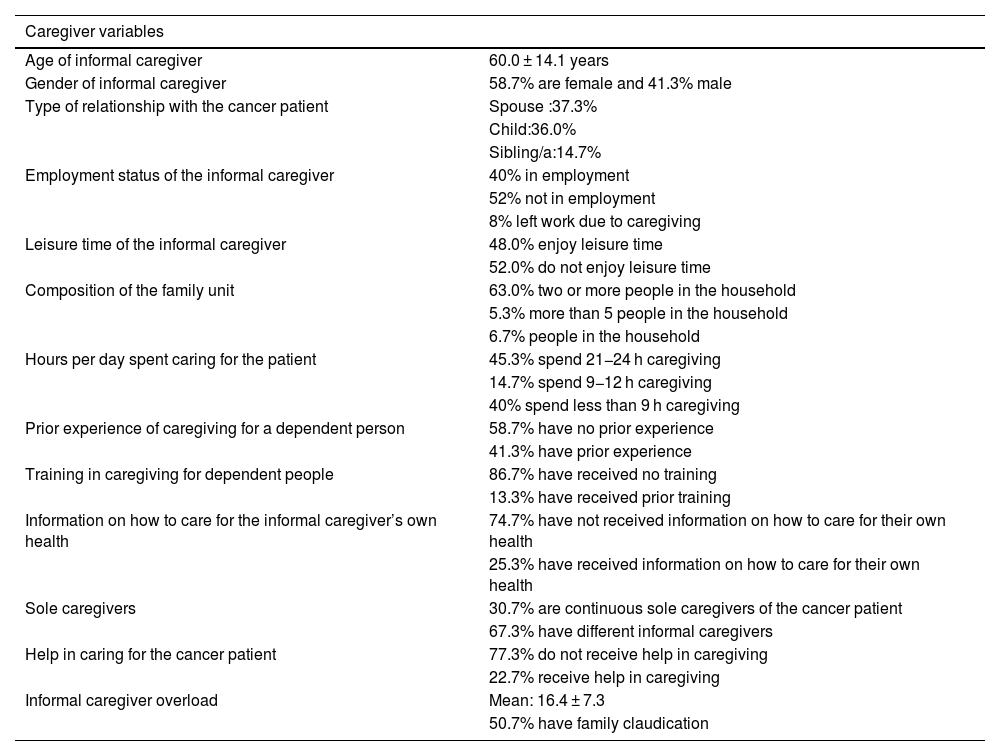

The mean age of the informal caregiver was 60 years (standard deviation ± 14.1). The gender distribution of the caregivers was not equal, with 58.7% were women and 41.3% men. In terms of the type of relationship with the patient, the following distribution was noted: 37.3% spouse, 36.0% child, and 14.7% sibling. Table 2 gives a detailed overview of the socio-demographic characteristics of the informal caregivers.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the informal caregiver of a cancer patient.

| Caregiver variables | |

|---|---|

| Age of informal caregiver | 60.0 ± 14.1 years |

| Gender of informal caregiver | 58.7% are female and 41.3% male |

| Type of relationship with the cancer patient | Spouse :37.3% |

| Child:36.0% | |

| Sibling/a:14.7% | |

| Employment status of the informal caregiver | 40% in employment |

| 52% not in employment | |

| 8% left work due to caregiving | |

| Leisure time of the informal caregiver | 48.0% enjoy leisure time |

| 52.0% do not enjoy leisure time | |

| Composition of the family unit | 63.0% two or more people in the household |

| 5.3% more than 5 people in the household | |

| 6.7% people in the household | |

| Hours per day spent caring for the patient | 45.3% spend 21−24 h caregiving |

| 14.7% spend 9−12 h caregiving | |

| 40% spend less than 9 h caregiving | |

| Prior experience of caregiving for a dependent person | 58.7% have no prior experience |

| 41.3% have prior experience | |

| Training in caregiving for dependent people | 86.7% have received no training |

| 13.3% have received prior training | |

| Information on how to care for the informal caregiver’s own health | 74.7% have not received information on how to care for their own health |

| 25.3% have received information on how to care for their own health | |

| Sole caregivers | 30.7% are continuous sole caregivers of the cancer patient |

| 67.3% have different informal caregivers | |

| Help in caring for the cancer patient | 77.3% do not receive help in caregiving |

| 22.7% receive help in caregiving | |

| Informal caregiver overload | Mean: 16.4 ± 7.3 |

| 50.7% have family claudication | |

The employment situation of the caregivers was as follows: 8% had to stop working to provide care, while 40% worked and provided care at the same time.

Regarding the caregivers' level of education, the following data were obtained: 40.2% had a basic level of education, 32% had university level education, 5.3% stated that they had no education. In addition, a total of 58.7% had no previous experience in caring, 86.7% had received no training in caring, 77.3% received no help in caring, and 76% had been caring for the patient for one year or more.

Of the total number of caregivers, 48.0% reported having leisure activities.

With regard to the variables studied, it was found that, in terms of level of overload, the overall mean score on the Zarit questionnaire was 16.4 ± 7.3. A total of 17.3% report the lowest score on the scale and therefore have the lowest level of overload, while 2.7% report the highest score on the scale and therefore have the highest level of overload. It should be noted that 50.7% were suffering family claudication. With regard to the degree of dependence, the mean total score on the Barthel Index is 39.7 ± 37.0, while in terms of degree of cancer-related fatigue, the mean total score on the PERFORM scale is 20.7 ± 12.3. It should be noted that 44% reported having the highest score on the scale and therefore the highest level of cancer-related fatigue.

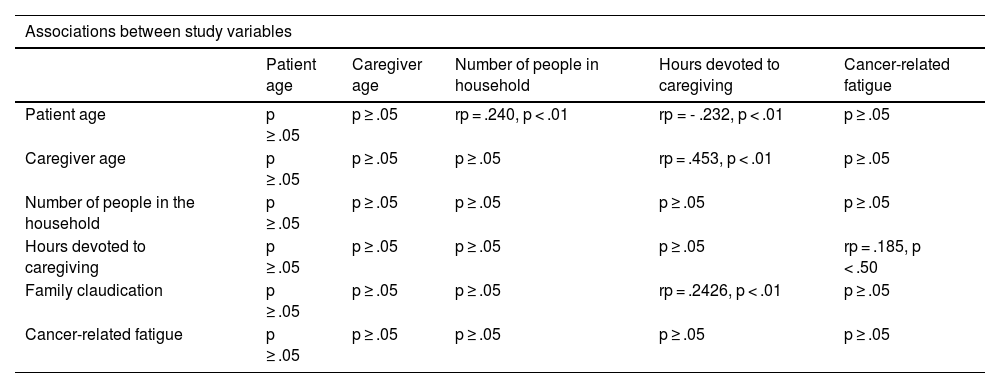

Analysing the association between the different variables under study, the following was observed (Table 3):

- -

A statistically significant, mean, directly proportional linear association (rp = .240, p < .01) between the patient's age and the number of cohabitants

- -

An association (rp = .453, p < .01) between the age of the caregiver and the total number of hours spent caregiving

- -

An association, (rp = .2426, p < .01) between family claudication and the number of hours spent caregiving.

- -

A statistically significant medium-low and inversely proportional linear association (rp = −0.232, p < .01) between patient age and the number of hours spent caring for the patient.

- -

A correlation (rp = .185, p < .50) between family claudication and a higher level of cancer-related fatigue.

Correlations between study variables.

| Associations between study variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient age | Caregiver age | Number of people in household | Hours devoted to caregiving | Cancer-related fatigue | |

| Patient age | p ≥ .05 | p ≥ .05 | rp = .240, p < .01 | rp = - .232, p < .01 | p ≥ .05 |

| Caregiver age | p ≥ .05 | p ≥ .05 | p ≥ .05 | rp = .453, p < .01 | p ≥ .05 |

| Number of people in the household | p ≥ .05 | p ≥ .05 | p ≥ .05 | p ≥ .05 | p ≥ .05 |

| Hours devoted to caregiving | p ≥ .05 | p ≥ .05 | p ≥ .05 | p ≥ .05 | rp = .185, p < .50 |

| Family claudication | p ≥ .05 | p ≥ .05 | p ≥ .05 | rp = .2426, p < .01 | p ≥ .05 |

| Cancer-related fatigue | p ≥ .05 | p ≥ .05 | p ≥ .05 | p ≥ .05 | p ≥ .05 |

And finally, the number of hours spent caring was found to be equal according to the gender of the caregiver (rp = .112, p < .50).

DiscussionThe main aim of the study was to analyse the current situation of overload in informal caregivers of cancer patients with cancer-related fatigue.

As mentioned above, cancer-related fatigue is one of the most common symptoms in cancer patients, characterised by difficulties in performing activities of daily living.

The results of the present study show that the care of cancer patients with cancer-related fatigue is provided by informal female caregivers, the first line of kin being the patient's wife and/or daughter, which may be the result of a cultural bias in which care is always provided to a greater extent by female relatives. These findings are in line with studies such as that of Daza Gallardo et al.17 on informal care for dependent older people, which found that the family plays a fundamental role in helping the dependent person and caring for the patient, with the majority of care provided by the woman, wife, and/or daughter in the family.

At a cultural level, care provision falls to women; this is reflected in our study and coincides with the research study by Prada et al.18 who state in their research study on haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis the predominance of the female gender in caregiving with a mean age of 50 years.

The average age of the informal caregivers in our study was 60 years, which is related to the age attributed in the studies by Franchini et al.19 and Alzehr et al.20, where the average age of the caregiver was 58 years and the caregiver-patient relationship was primarily that of spouse, followed by son or daughter. Similarly, in this study we observe how caregiving continues to be associated with cultural concepts in the first line of kinship.

The results obtained from the Barthel Index show that 45.3% of the patients have a high level of dependence and the results obtained from the PERFORM questionnaire show that up to 44% of the sample present extreme cancer-related fatigue. Furthermore, it can be seen that the higher the patients’ level of cancer-related fatigue, the higher the level of dependence, which is logical if it is understood as an increase in symptoms leading to a deterioration in health-related quality of life parameters.

The patients with cancer-related fatigue in our study have physical limitations and a state of dependence that requires help from the informal caregiver. This statement is consistent with the need to increase care aimed at reducing the dependence of the individual, and how this reduction in dependence would lead to improvements not only in the patient but also in their environment. This is in line with the study by Tripodoro et al.21 on the burden of informal caregivers of cancer patients in palliative care at the University Hospital of Buenos Aires, who found that up to 43% of caregivers had a severe burden, followed by 24% of caregivers with a slight burden. Up to 68% of the patients in this study who were informal caregivers had an ECOG 3–4, and the relationship between dependence and primary caregiver burden is noteworthy.

Analysing the existing literature, we also found similarities with the study by Rodríguez and Rihuete22 on oncology patients in the home setting and in the oncology ward in Salamanca. These authors conducted a study in 2011 of 95 cancer patients and caregivers, in which up to 57% of patients showed some level of dependence and up to 45% of caregivers showed caregiver overload. These investigators concluded that the greater the dependence of the patient, the greater the overload of their informal caregivers, indicating that high levels of dependence in patients at home pose a significant risk of overload in their caregivers.

We also find overload in other diseases in other studies, such as the research study by Arias-Rojas et al.23 or Madrid et al.24, who state that as the dependence of patients with dementia increases, so does the overload of their caregivers. Other conclusive data are found in the study by Fang et al.25 in relation to dependent chronic renal patients at the General Hospital of Tampico, in which 40% of caregivers presented a high level of overload, followed by 26% with a slight level of overload.

Finally, our results show that 50.71% of the participating caregivers were suffering family claudication, 58.7% had no experience in caregiving, 80.7% had no training, and 77.3% had not received any support or help from the family, community, or social environment. This is directly related to studies by Benthien et al.,26 Caruso et al.27, and Duimering et al.28

Caregiving experience, training and, above all, family, community, and social support may mark the overload of the informal caregiver of the patient with cancer-related fatigue. In this regard, we highlight the study by Daza Gallardo et al.17 on lung cancer, which shows how important the support factors of the patient's relatives, or even the age of the informal caregiver, are in family claudication, since this determines the caregiver's level of fatigue.

In terms of the limitations of the present study, we could point out the lack of confidence on the part of the informal caregivers to show the level of subjective fatigue, this fatigue could condition the answers given, as they consider their care a moral obligation, and secondly, the sample size is not very large, which could affect the interpretation of the results of the variables studied in the form of bias. However, we believe that it is indeed representative and important to carry out a first study that provides the necessary evidence both for informal caregivers of patients and for cancer patients with cancer-related fatigue themselves.

In future research, we intend to extend this study to further detail the aetiology, consequences, and coping strategies for informal caregivers of cancer patients at any stage of the disease. This will increase our knowledge of this alarming symptom and allow us to identify the best care strategies to mitigate or compensate for it from a healthcare and nursing perspective.

ConclusionOverload in caregivers of cancer patients with cancer-related fatigue is present in more than one third of caregivers of patients in the Medical Oncology Service of the Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca (CAUSA) and the Palliative Care Unit of the Hospital de los Montalvos. There are variables that influence the perception of this overload, such as the age of the patient, the age of the main caregiver, the number of hours of care, and the willingness to ask for help, further aggravating, if possible, this overload and therefore the effective care of the patient. We believe that greater care intervention in this type of individual would improve not only the clinical outlook of the patients, but also that of those who form part of their care network, and we consider nurses to be the cornerstone of this type of intervention.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availabilityThe raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

We would like to thank all the people who altruistically wanted to take part in the study, without them the study could not have been conducted.