This quasi-experimental, pre-/post-test study aimed to examine the effect of a community-based spiritual life review program on the resilience of elders residing in a disaster-prone area.

MethodFifty-two participants who met the inclusion criteria were recruited from three villages in the Kutaraja sub-district in Banda Aceh, Indonesia. The participants were randomly assigned to an experimental group and a control group. The participants’ names were listed and then randomly selected by a random number generator. The experimental group underwent a community-based spiritual life review program, which included a review of their spiritual lives, the appreciation of feelings, affirmation by the religious leader, a reevaluation of their lives, and a reconstruction of their lives to recognize their memories and present feelings.

ResultsThe elderly resilience scores were evaluated four weeks after the program was implemented. The control group received the same program after the study was finished. The participants in the experimental group significantly improved their resilience levels after completing the program (p < .05). There was a slight increase in the resilience scores from the pre-test to the post-test in the experimental group compared with the control group (p < .05).

ConclusionsFuture studies should add implementation sessions and avoid photos that would induce participants’ traumatic memories or experiences during the spiritual life review.

Disasters are categorized as the most significant catastrophe in the world1. Disasters often occur suddenly, caused by natural phenomena such as tsunamis, earthquakes, storms, flooding, and volcanic eruptions. Disasters are occurring at an unprecedented rate worldwide2 Indonesia is a country with a high risk of disaster. It is located in the Pacific “Ring of Fire”, which experiences frequent earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. The Ring of Fire is associated with a series of oceanic trenches and volcanic mountain ranges or plate movements3.

Elderly people are more vulnerable to the psychosocial effects of a disaster4. Istiany reported that hundreds of elders suffered from mental disorders after the earthquake and tsunami in Aceh, Indonesia5. Many aspects of elder’s life are vulnerable including the biological, psychological, economic, and social aspects6. The biological factor is the degeneration of cells during the aging process7. From psychological factors include frustration, loneliness, and depression6. Then the economic changes include the lack of financial support after a disaster8. Finally, social aspect related to the sociological change of elders. The elderly who lose their family members and live alone need specific care from others during a disaster. The elders who are living alone appear to have a worse health status and health risk behaviors than those living with others9.

Maneerat10 identified five major components of elderly resilience: positive physical function, positive emotional function, effective coping strategies, spiritual support, and social support. She revealed that social support and spiritual support have impact on the elders’ resilience. Olphen et al.11conducted a household survey with 679 elderly respondents in the United States. They found that social support and spiritual support through religious involvement had a positive influence on health in general. Thus, the resilient elderly tend to have better health. A study by the Australian Association of Gerontology12 indicated that the elderly with lower resilience have less vitality, limited role performance, and worse self-perceived health than those with higher resilience.

Elders who face adversity should have high resilience to maintain their health12. Health care provider need to develop a program combining spiritual support and social support to enhance elders’ resilience. Several researchers have indicated that a life review program enables elders to enhance their spiritual well-being13–15 and is beneficial and cost effective16. The life review allows participants to review, appreciate, reevaluate, and recognize their own lives. Ando et al.14 created some questions to review the participants’ past experience and used pictures as a medium to express their stories. Through the past life story telling about the impressive memory, significant contribution in life and important role in life enable participants gain social support. Appreciating and religious affirmation on one’s past life may also contribute to spiritual support among participants.

Nurses in the community can help older adults develop new programs to meet their psychosocial and developmental needs through the spiritual life review program17. By doing so, the older persons can review and evaluate their life experiences by exploring the meaning of memorable events in their lives and obtaining social support from their peer group in the neighborhood.

The spiritual life review program is appropriate for Indonesian elders. The cultural and social activities in the community involve religious belief. The people attend religious affirmations by religious leaders, pray together in the mosque, and conduct community meetings in the mosque. However, limited collaboration exists between nurses and the community resources such as religious leaders in terms of health promotion activities. The community-based spiritual life review program aims to promote resilience among elders who live in disaster-prone areas. The community is expected to show high acceptance of this developing program if it is introduced from collaboration nurses and religious leaders.

In this study, the researchers added to the existing studies13,15,18 by examining the effectiveness of a community-based spiritual life review program in promoting the resilience of Indonesian elders living in a disaster-prone area. The results will be used for further community-based programs to promote resilience among the elderly population.

MethodThis quasi-experimental study used a two-group pre-test and post-test design to examine the effect of a community-based spiritual life review program on promoting resilience among Indonesian elders residing in a disaster-prone area of Banda Aceh, Indonesia. The experimental group underwent the community-based spiritual life review program. The control group received similar program after the study had finished.

The target setting of this study was the Kutaraja sub-district of Banda Aceh. This sub-district was purposively selected because it was seriously affected by the 2004 tsunami. Earthquakes still occur throughout the year in this region. The Kutaraja sub-district contains six villages: Keudah, Peulanggahan, Merduati, Lampaseh Kota, Gampong Pande, and Gampong Jawa. All of these villages are categorized as sub-urban because they are located near the city of Banda Aceh.

The sample was determined using power analysis based on the effect size of a previous study (Ando et al., 2008) regarding the life review program, which included reevaluating and appreciating previous life experience as well as group’s album. The group’s album is consists of the photos that the participants chose in term to express their feeling in the program. The program was conducted in two sessions within a four-week intervention. According to Cohen19, the necessary sample size for a significance level of α=.05, power=.80, and effect size (d)=1.00 was a minimum of 17 subjects per group. However, in the present study, the sample size was increased by 50% to 26 subjects per group or a total of 52 subjects. The researchers increased the sample size because of the different setting and refer to one study from the pilot study. A pilot study was conducted to evaluate the feasibility of the protocol20. The protocol consists of guidelines of the program which is develop and modified by researchers. In the pilot study, 12 elders met the inclusion criteria and joined the community-based spiritual life review program. Generally, the program was applicable to the present study.

The present study used the Elder Resilience Scale Questionnaire (ERSQ), which consists of 24 items originally developed by Maneerat10. The questionnaire has five dimensions: being able to join with people (6 items), being confident in life (5 items), having social support (4 items), living with spiritual security (4 items), and being able to de-stress and manage problems (5 items). Each item was measured using a 4-point Likert scale (1=disagree, 2=partially agree, 3=quite agree, 4=completely agree). Higher total and subscale scores indicate higher spiritual resilience. Statistically, this tool has been proven a reliable and valid measure of resilience10.

Content validity was applied to test the instrument validity. The intervention program/protocol and ERSQ were validated by three experts: one expert in psychiatric nursing from the Faculty of Nursing at the Prince of Songkla University, one expert in community nursing from the Faculty of Nursing at the Prince of Songkla University, and one foreign expert from the College of Islamic Studies at the Prince of Songkla University, Pattani campus. All experts agreed on the validity of the instruments after proposing corrections to the wording of some items, adding a game, and adding an evaluation at the end of the session in the community-based spiritual life review program.

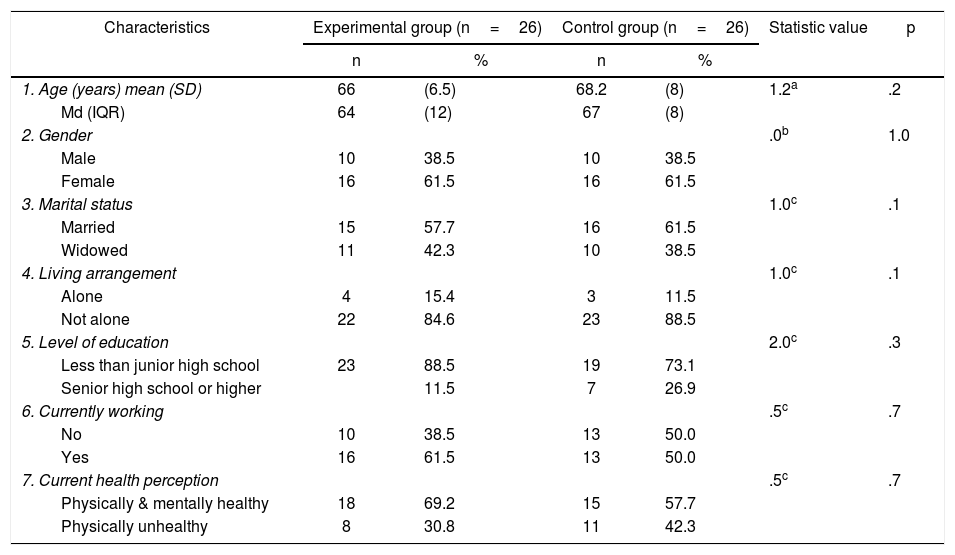

The demographic data were described using frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations (Table 1). The chi-square test and Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare the demographic data of the experimental and control groups. In cases where more than 20% of the expected frequencies in a 2 × 2 contingency table were too small, Fisher’s exact test was used instead of the chi-square test. All data were measured and treated as a continuous variable for normality and homogeneity of variance when needed. The normality was determined by dividing the skewness and kurtosis by their respective standard errors, and results less than 3 were considered an acceptable level of normality. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was also used to assess normality. The homogeneity of variance was determined using Levene’s test.

Demographic characteristics of the experimental and control groups (N=52).

| Characteristics | Experimental group (n=26) | Control group (n=26) | Statistic value | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| 1. Age (years) mean (SD) | 66 | (6.5) | 68.2 | (8) | 1.2a | .2 |

| Md (IQR) | 64 | (12) | 67 | (8) | ||

| 2. Gender | .0b | 1.0 | ||||

| Male | 10 | 38.5 | 10 | 38.5 | ||

| Female | 16 | 61.5 | 16 | 61.5 | ||

| 3. Marital status | 1.0c | .1 | ||||

| Married | 15 | 57.7 | 16 | 61.5 | ||

| Widowed | 11 | 42.3 | 10 | 38.5 | ||

| 4. Living arrangement | 1.0c | .1 | ||||

| Alone | 4 | 15.4 | 3 | 11.5 | ||

| Not alone | 22 | 84.6 | 23 | 88.5 | ||

| 5. Level of education | 2.0c | .3 | ||||

| Less than junior high school | 23 | 88.5 | 19 | 73.1 | ||

| Senior high school or higher | 11.5 | 7 | 26.9 | |||

| 6. Currently working | .5c | .7 | ||||

| No | 10 | 38.5 | 13 | 50.0 | ||

| Yes | 16 | 61.5 | 13 | 50.0 | ||

| 7. Current health perception | .5c | .7 | ||||

| Physically & mentally healthy | 18 | 69.2 | 15 | 57.7 | ||

| Physically unhealthy | 8 | 30.8 | 11 | 42.3 | ||

Fifty-two elders were included in the study. The average age of the participants was 66 years (SD=6.5) in the experimental group and 68 years (SD=8) in the control group. In both the experimental group and the control group, more than half of the participants were female (61.5%). More than half of the participants were married (57.7% in the ex-perimental group and 61.5% in the control group). The ma-jority of participants lived with their family (84.6% in the experimental group and 88.5% in the control group). Most of the participants had a low level of education (88.5% in the experimental group and 73.1% in the control group). More than half (61.5%) of the participants in the experimental group had a job, compared with 50.0% in the control group. The majority (69.2%) of participants in the experimental group perceived themselves as physically and mentally healthy, as compared to 57.7% in the control group. The demographic characteristics did not differ significantly between the experimental group and the control group.

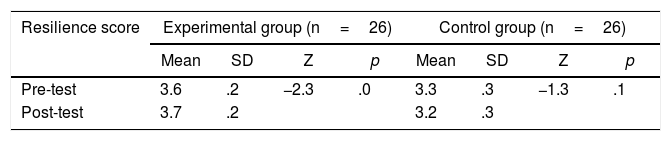

The effect of the community-based spiritual life review program within groupsTable 2 shows that the participants in the experimental group had significantly higher resilience scores after participating in the community-based spiritual life review program (Z=–2.4; p < .05). Because the variable did not meet the assumption of parametric statistics, the Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare the pre-test and post-test resilience scores within groups. The mean pre-test resilience score of the experimental group was 3.6 (SD=0.2), and the mean post-test resilience score was 3.7 (SD=0.3). In the control group, the mean pre-test and post-test resilience scores were 3.3 (SD=0.3) and 3.2 (SD=0.3), respectively. The data revealed no significant difference in resilience scores after implementing the program in the control group (Z=–1.3; p=.1).

Comparison of the pre-test and post-test resilience scores within the experimental and control groups (N=52).

| Resilience score | Experimental group (n=26) | Control group (n=26) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Z | p | Mean | SD | Z | p | |

| Pre-test | 3.6 | .2 | −2.3 | .0 | 3.3 | .3 | −1.3 | .1 |

| Post-test | 3.7 | .2 | 3.2 | .3 | ||||

Z=Wilcoxon signed rank test; df=25.

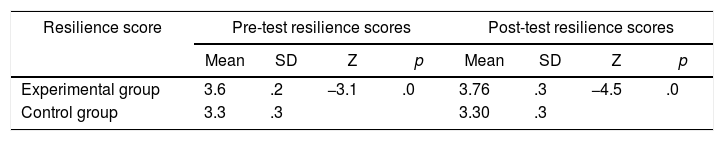

The Mann-Whitney U test was used to examine the differences in the pre-test and post-test resilience scores between the experimental group and the control group. The mean pre-test resilience score was 3.6 (SD=0.2) in the experimental group and 3.3 (SD=0.3) in the control group. Table 3 shows a significant difference in pre-test resilience scores between groups (Z=–3.1; df=50; p=.0). The mean post-test resilience score was 3.7 (SD=0.3) in the experimental group and 3.3 (SD=0.3) in the control group. The post-test resilience scores differed significantly between groups (Z=–4.5; p=.0).

Comparison of pre-test and post-test resilience scores between the experimental group and the control group (N=52).

| Resilience score | Pre-test resilience scores | Post-test resilience scores | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Z | p | Mean | SD | Z | p | |

| Experimental group | 3.6 | .2 | −3.1 | .0 | 3.76 | .3 | −4.5 | .0 |

| Control group | 3.3 | .3 | 3.30 | .3 | ||||

Z=Mann-Whitney U test; df=50.

Since the pre-test scores differed significantly between the experimental and control groups, the mean difference scores (post-test score minus pre-test score) were constructed to counterbalance the effect of the pre-test score. The independent t-test was used to analyze the betweensubject effect of the program.

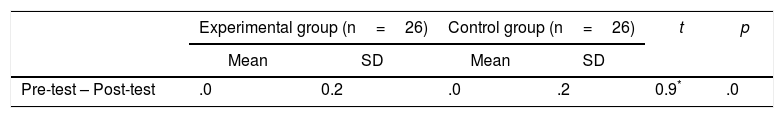

Table 4 shows a significant difference in resilience scores between groups (t=.9; p=.0), although this effect was smaller than before controlling for the pre-test score (p=.0). This study was supported by the finding that Indonesian elders residing in a disaster-prone area who underwent a community-based spiritual life review program had higher resilience than those who did not undergo the program.

Comparison of the in mean difference pre-test and post-test resilience scores of the experimental group and control group (N=52).

| Experimental group (n=26) | Control group (n=26) | t | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Pre-test – Post-test | .0 | 0.2 | .0 | .2 | 0.9* | .0 |

df=50.

The results of this study support both hypotheses, demonstrating that participating in the community-based spiritual life review program resulted in significant improvements to the elderly’s resilience. Their resilience significantly improved from the pre-test to the post-test (Table 2). Comparing the experimental group and the control group, the participants who participated in the program had significantly higher resilience than those who did not participate in the program (Table 2).

The present study evaluated the improvement in resilience scores one week after the program was initiated. Previous studies reported an improvement at two weeks13 and at one week14. According to Ando et al.15 a short-term life review is more feasible than long term program.

The life review program is an intervention that has been empirically proven to be useful to the elderly14,15. To promote resilience, the present study added components to the life review, including spiritual affirmation and social support through neighborhood peer groups. Spiritual support and social support are significant contributors to elders’ resilience10.

There were several factors underpinned the positive outcomes of this study, such as establishing rapport with the elders, reviewing their lives, appreciating their feelings, affirmation by the religious leader, reevaluating their lives by looking at the group’s album, and reconstructing their lives by recognizing their memories and present feelings. The following sections will explain each factor in detail.

First, after the introduction stating the purpose of the meeting, the goal of the program, and the rules, the researchers held a storytelling activity to make the participants relaxed and feel free to participate in the program. The storytelling enabled the participants to laugh and enjoy themselves. Considering the group dynamic, the facilitator should establish good rapport to make the group more cohesive21.

Reviewing spiritual lifeThe questions for reviewing the participants’ spiritual lives were based on the previous studies14,15. However, the present study focused only on reviewing difficulties in life, such as the 2004 tsunami. Through this process, the participants were able to express their spiritual experiences during hardships. Some of them chose photos and share their spiritual experience during the tsunami based on those photos. Each of them had their own story to tell. Some stories reflected good memories; for instance, many remembered God’s existence and the solidarity and strengthening of humanity after the tsunami. The participants also expressed sad memories such as how they survived during the tsunami and how they lost their family members and relatives.

Bohjeimer22 reported that females focus more on emotional experience than males do. In the present study, males shared how they adapted to the hardship, whereas females only expressed their feelings. Therefore, the researchers grouped the participants by gender to enable them to share and express their feelings freely. The group session helped the participants relate to each other in different ways with regard to the tsunami experience. Some of them showed how they were able to cope with the situation, while the rest of them learned from the experiences that were shared.

Appreciating feelingsDuring the review of their life experience, the participants were invited to share their feelings freely to receive the group’s support. Some of the participants showed their appreciation and empathy by touching others’ hands, while others listened and explained how they adapted to the sad situation. McKinley18 reported that non-verbal behavior, joking, affirmation, and questioning each other enabled participants to talk to each other more freely. Ando et al.15 revealed that participants were able to recognize the importance of communication in improving hope and feelings about relationships. Having good relationships enables participants to receive social support from their neighborhood peer group. Social support plays an important role in resilience10,11.

Affirmation by a religious leaderThe religious affirmation based on six spiritual dimensions was adapted from Mackinlay18. In the present study, the researchers focused on the Islamic religion, where the religious leader follows the discussion in the beginning as an active listener, as opposed to the old model of spiritual affirmation, in which participants were passive subjects who had to listen to the religious speeches. Using the new model, the religious leader is more understanding of the participants’ thoughts and knows their spiritual needs. Peres et al.23 found that higher levels of religious involvement are associated with greater well-being and mental health. Maneerat10 and Olphen et al.11 reported that religious involvement was a significant contributor to resilience.

Reevaluating lifeThe group album was collated from the photos chosen by the participants in the first session. The participants were able to recall good and sad memories. They planned for a positive future. This was congruent with Bohlmeijer's22 finding that reevaluation process opened up new possibilities and plans to enhance personal value. The new possibilities were created for strengthen awareness. Most participants were confident to live their lives by working and performing religious practices. They believed that the disaster was God’s doing and that God had a reason to bestow something bad or good on the human race. At the end of the session, the participants remembered the story about Ummu Salamah, who was rewarded by God for her patience during difficulties. Ando et al.15 revealed that through the reevaluation process, the participants were able to increase their spiritual well-being.

Besides the effect of the community-based spiritual life review program, this study identified other factors associated with the participants’ resilience. These include the timing of the intervention and the religious and cultural background.

Timing of the interventionThe community-based spiritual life review program was conducted eight years after the 2004 tsunami in Banda Aceh. Although earthquakes still occur frequently, the majority of people continue to live in coastal areas. They believe that their death is in God’s hands. Therefore, the pre-test resilience scores were high in both experimental and control groups.

Religious and cultural backgroundThe majority of people in Banda Aceh have a strong Islamic culture. The local government upholds the Islamic laws in Aceh province. Islamic religion teaches that as Muslims, people have to be patient in vulnerable conditions and never surrender during hardship. In this study, the pre-test score for the sub-scale of spiritual security was high (M=3.9, Md=4.0).

The findings also revealed a slight increase in the mean resilience score from the pre-test (M=3.6) to the post-test (M=3.7) in the experimental group. Two of the sub-scales showed a decreasing resilience score: spiritual security and confidence in life. The specific photos related to the past tsunami, which were provided by the researchers, may have induced the participants’ sad memories. During the session, many participants told their sad stories. The researchers observed two participants who cried while they reviewed their spiritual lives during the tsunami.