We present the case of a 30-year-old patient, originally from Gambia and resident in Spain for two years, with no relevant medical history or known allergies. The patient came to Accident and Emergency at Palamós Hospital (regional hospital) with a month-long history of headache, photophobia, febricula and general malaise, accompanied in the previous week by hyporexia, generalised asthenia and night sweats. Initial testing, including complete blood count, urinary sediment and acute phase reactants, was normal.

Brain computerised tomography (CT) showed dilation of the supratentorial ventricular system with signs of activity and ependymal effusion. Lumbar puncture revealed cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) glucose levels of 30 mg/dl, proteins 349 mg/dl, leucocytes 350/mm3, polymorphonuclear 72% and ADA 14 U/l, suggesting probable bacterial meningitis complicated by hydrocephalus. The patient was admitted to the Intermediate Care Unit (IMCU), and empirical treatment was started with ampicillin, aciclovir, rifampicin and dexamethasone.

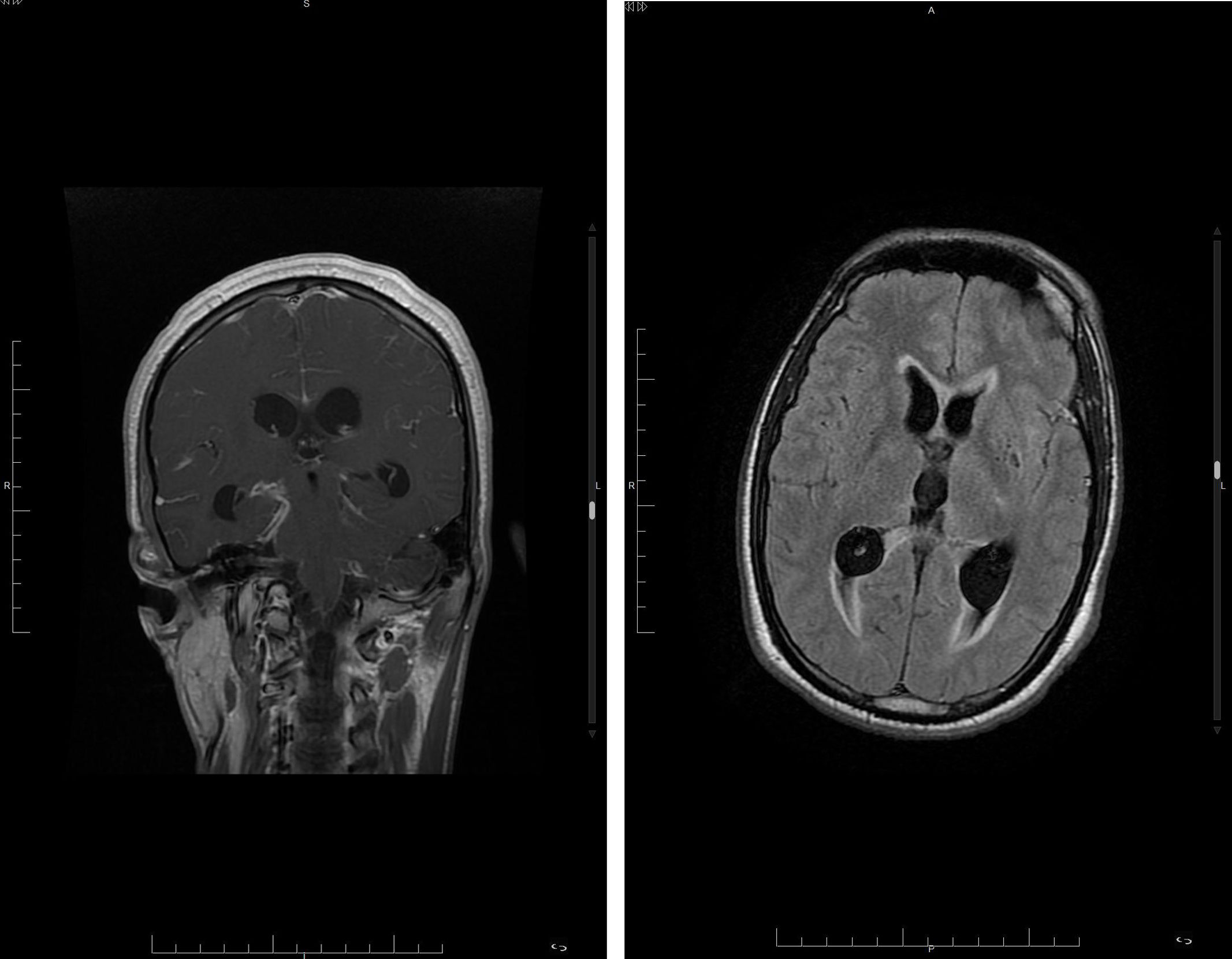

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 1) showed findings consistent with acute meningitis with leptomeningeal uptake, ventriculitis and signs of ischaemic complication in the left internal capsule. CSF polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (GeneXpert MTB/RIF Ultra®) was positive for rifampicin-sensitive Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC), and tuberculous meningitis was diagnosed. Tuberculosis treatment was adjusted with rifampicin, isoniazid, streptomycin, linezolid and dexamethasone.

Magnetic resonance images. Left: Coronal T1 sequence showing meningeal enhancement, predominantly in the basal cisterns. Right: Axial T2 FLAIR sequence; note the increase in ventricular size with fluid-fluid level in both occipital horns and areas of hyperintensity in the periventricular white matter.

After 72 hours in the IMCU, the patient’s state of consciousness deteriorated (Glasgow Coma Scale 8) and he became haemodynamically unstable, requiring intubation and transfer to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) in a more specialised hospital (Hospital J. Trueta, in Girona), where treatment was adjusted to rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethionamide and dexamethasone.

In the ICU, the patient developed several complications, including left mydriasis and bradycardia secondary to hydrocephalus, receiving treatment with mannitol and external ventricular drainage (EVD), ventriculitis treated with ganciclovir, tracheobronchitis associated with intubation (due to multi-drug-sensitive Escherichia coli) and EVD infection treated with vancomycin and meropenem, eventually becoming haemodynamically stable but neurologically in a coma. Subsequently, the patient developed pneumonia secondary to bronchial aspiration, and treatment was changed to rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and levofloxacin, with little response. The patient eventually died four weeks after his initial admission due to respiratory complications and hydrocephalus.

At this same time, at the regional hospital, Lowenstein’s culture was found to be positive and the strain was sent to the reference centre (Vall d’Hebron Hospital) where Mycobacterium africanum (M. africanum) lineage 6 was identified, with the result being received a few days after the patient’s death.

The detection of M. africanum in cases of tuberculous meningitis in Spain introduces a new and worrying aspect to the epidemiology of this disease. Tuberculous meningitis represents a medical challenge due to its serious and potentially lethal nature1,2 and is a rare manifestation of extrapulmonary tuberculosis.

Its prevalence in Spain is low, only making up 1% of all tuberculosis cases, but it has an alarming mortality rate of 40–50%, highlighting the urgency of early diagnosis and treatment. Limitations to the management of tuberculous meningitis3,4 include its nonspecific clinical presentation, which delays diagnosis, and suboptimal antimicrobial regimens. In addition, although progress has been made with molecular tools, the sensitivity of the available diagnostic techniques is insufficient.

M. africanum is a member of the MTBC. It was first described in 1968. Its distribution is variable across Africa; it has demonstrated an ability to adapt and evolve in different ecological environments.5,6 It is exclusively pathogenic for humans. The various lineages and sublineages of M. africanum (L5, L6 and L9) are located in specific areas of Africa. L6 strains are prevalent in countries such as Guinea Bissau, Sierra Leone and Gambia.

Considering that M. africanum is predominant in Africa and that the patient had resided in Spain for the previous two years, it is likely that he had become infected in his country of origin, but that he had remained asymptomatic. Being an immunocompetent patient with no previous history of tuberculosis or signs of pulmonary involvement at the time of his illness, it is of note that meningitis was the first sign of tuberculosis reactivation.

The finding of M. africanum is an indicator of transmissibility and latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI). In our clinical case, the application of recommendations7 for the screening of LTBI, developed by healthcare professionals and epidemiologists, which include strategies for systematic detection and treatment in risk groups, could have facilitated early detection and appropriate treatment, possibly avoiding the fatal outcome. Preventing active TB through LTBI treatment is a critical component of the WHO’s strategy to eliminate TB.

Creating strategies is crucial to reduce transmission and establish epidemiological links that prevent the spread of the disease.