Lyme disease (LD) is a bacterial infection transmitted by ticks. In Spain, the annual incidence is 0.25 cases per 100,000 population, and is higher in the northern half of the country.

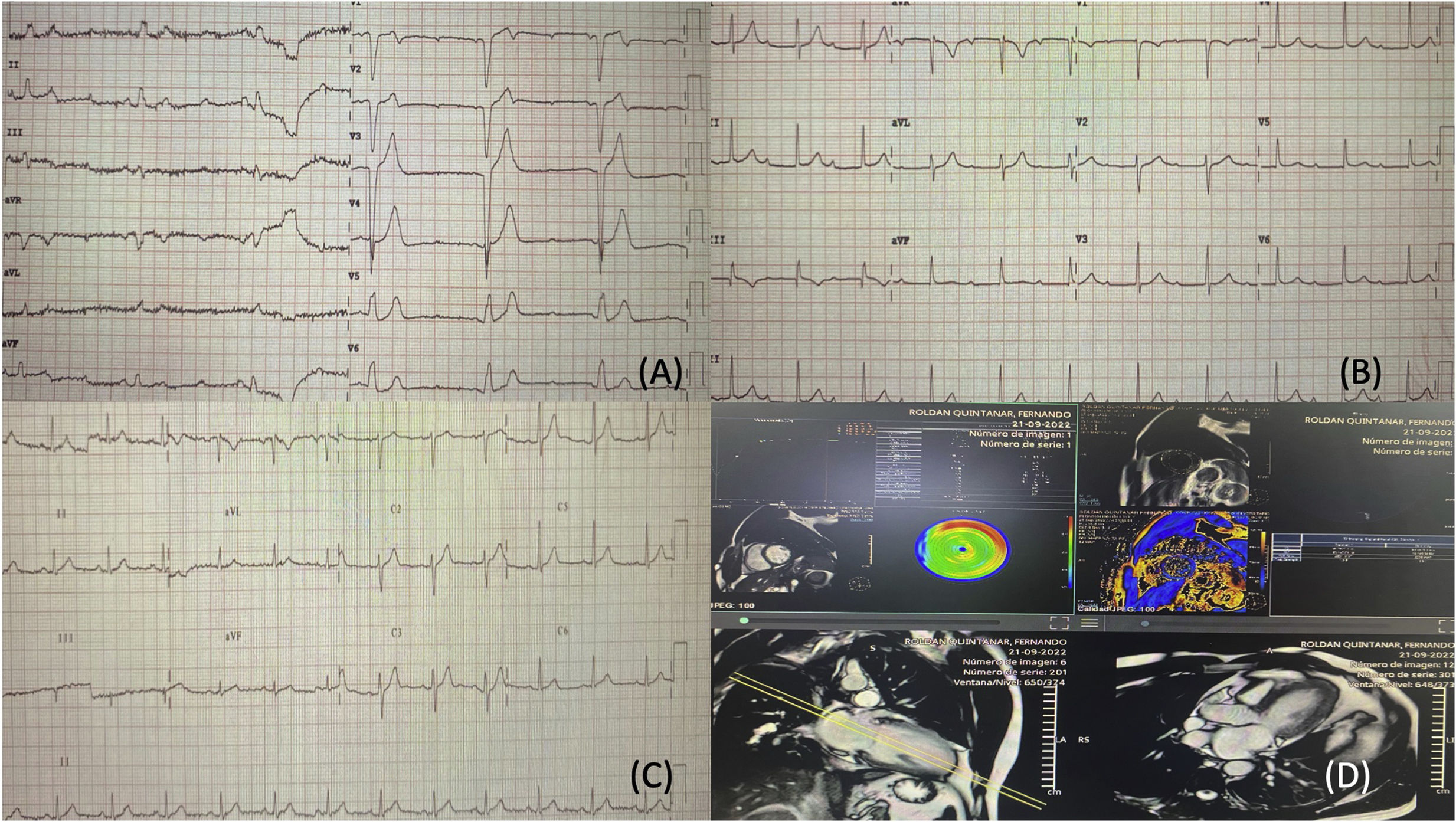

We present the case of a 31-year-old male with no previous relevant medical history. He consulted with asthenia and dyspnoea on effort, with worsening in recent days, cervicalgia and myalgia without associated fever. He reported having been bitten by a tick the month prior to the consultation during a trip to Asturias. The physical examination revealed a temperature of 37 °C, blood pressure of 150/61 mmHg, a heart rate of 54 bpm with a grade 2/6 systolic murmur on the left sternal border. The first electrocardiogram performed (Fig. 1A) showed complete atrioventricular block (AVB) with a wide QRS complex and complete left bundle branch block (LBBB) morphology. Blood tests (normal values in brackets) showed a deterioration in renal function with creatinine 1.34 mg/dl (0.7–1.2 mg/dl), 13,280 leucocytes/μl (4000–10,000/μl) with neutrophilia and C-reactive protein 18.1 mg/dl (<0.3 mg/dl), high sensitivity troponin 260 mg/dl (0–14 mg/dl) and creatinine kinase 345 U/l (38–174 U/l). Echocardiography showed left ventricle function to be normal (58%), without other findings.

A) Initial ECG showing complete AVB with wide QRS and complete LBBB morphology. B) Changes after two weeks of antibiotic therapy, ECG with first-degree AVB and narrow QRS. C) Changes after one month of antibiotic therapy, ECG in sinus rhythm (SR) with narrow QRS. D) Cardiac MRI showing focal enhancement pattern in the inferolateral, superolateral and anteroseptal surfaces.

Given the presence of complete AVB, treatment with isoprenaline was started, he was admitted to the cardiovascular critical care unit and a right jugular introducer was inserted due to the probability of needing a temporary pacemaker. Applying the Suspicious Index in Lyme Carditis (SILC)1 score, Lyme carditis was strongly suspected. Blood cultures, urine cultures, serologies and analyses, including autoimmune tests, were performed to rule out other infectious diseases, as well as systemic diseases, which can cause complete AVB in young patients, and antibiotic therapy was started with intravenous ceftriaxone 2 g every 24 h pending the results of these tests. A pacemaker was not implanted as secondary complete AVB is usually transient,2 resolving with antibiotic therapy in most cases.3 Serology confirmed Borrelia burgdorferi infection with positive IgM and IgG, autoimmunity tests were negative and cardiac MRI was consistent with myocarditis; the main suspected diagnosis was therefore confirmed, maintaining the same treatment (Fig. 1D). After six days of treatment, the myocardial damage markers began to decrease, with progressive recovery of atrioventricular conduction and narrowing of the QRS, but the first-degree AVB persisted (Fig. 1B). After completing two weeks of treatment and given the patient’s good progress and the resolution of his complete AVB, he was discharged on oral cefuroxime 750 mg every 12 h for two weeks, to complete the one-month course of treatment. At discharge, the patient had first-degree AVB with a PR interval of 202 ms (Fig. 1C). The patient was assessed one month later in the clinic, and was found to be asymptomatic. Electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with a PR interval of less than 200 ms, with no other changes.

Complete AVB occurs in 80%–90% of cases of Lyme carditis1 and is an early cardiac manifestation. Due to the therapeutic implications of complete AVB, a high degree of suspicion is crucial,4 and different scales can be used for this; the SILC score assigns points to six items: constitutional symptoms (2 points), activities in endemic areas/outdoors (1 point), being male (1 point), tick bite (3 points), age under 50 years (1 point) and erythema migrans (4 points). The patient in this case met the first five criteria, with a total of 8 points, and according to this scale, a high degree of suspicion should be considered from 7 points and above. It is important to order tests to make a differential diagnosis between the different causes of complete AVB in young patients, ruling out other infectious diseases (viral myocarditis, those caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, endocarditis with paravalvular abscess formation,5 Chagas’ disease6 or Q fever), systemic diseases (sarcoidosis,7 rheumatic fever,8 ischaemic heart disease, infiltrative diseases [amyloidosis] and degenerative diseases [Lenegre’s disease] and myotonic dystrophy).9 Initial antibiotic therapy should be intravenous, and ceftriaxone 2 g/12 h for 14 days is recommended; if the response is good, this should be followed by oral treatment with doxycycline 100 mg/12 h, amoxicillin 500 mg/8 h or cefuroxime 500 mg/12 h.1