HIV infection has become a chronic disease with a good long-term prognosis, necessitating a change in the care model. For this study, we applied a proposal for an Optimal Care Model (OCM) for people with HIV (PHIV), which includes tools for assessing patient complexity and their classification into profiles to optimize care provision.

MethodsObservational, cross-sectional, and retrospective study. Adult PHIV treated at the Tropical Medicine consultations at Ramón y Cajal Hospital from January 1 to June 30, 2023, were included. The complexity calculation and the stratification into profiles for each patient were done according to the OCM.

ResultsNinety-four participants were included, 76.6% cisgender men, with a median age of 41 years (range 23−76). Latin America and Africa were the main regions of origin (72.4%). 98% had an undetectable HIV viral load. The degree of complexity was 78.7% low, 11.7% medium, 1% high, and 8.5% extreme. The predominant profile was blue (64.9%), followed by lilac (11.7%), purple (6.3%), and green (4.3%). 7.4% were unclassifiable, of whom 57.2% had high/extreme complexity. Among the unclassifiable, mental health problems were the most common.

ConclusionsThe OCM tools for People Living with HIV (PLWH) allow for the classification and stratification of most patients in a consultation with a non-standard population. Patients who did not fit into the pre-established profiles presented high complexity. Creating a profile focused on mental health or mixed profiles could facilitate the classification of more patients.

La infección por VIH se ha convertido en una enfermedad crónica con buen pronóstico a largo plazo, lo que obliga a un cambio en el modelo asistencial. Hemos aplicado una propuesta de Modelo Óptimo de Atención (MOA) a personas con VIH (PVIH) que incluye herramientas de evaluación de la complejidad de los pacientes y su clasificación en perfiles, para optimizar la oferta de cuidados.

MétodosEstudio observacional, transversal y retrospectivo. Se incluyeron PVIH adultas atendidos en las consultas de Medicina Tropical del Hospital Ramón y Cajal, desde el 1/enero al 30/junio del año 2023. Se procedió al cálculo de la complejidad y la estratificación en perfiles según el MOA.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 94 participantes, 76,6% hombres cisgénero, con una mediana de edad de 41 años (rango 23−76). América Latina y África fueron las principales regiones de origen (72,4%). El 98% tenían carga viral del VIH indetectable. El grado de complejidad fue: 78,7% baja, 11,7% media, 1% alta y 8,5% extrema. El perfil predominante fue el azul (64,9%), seguido del lila (11,7%), morado (6,3%) y el verde (4,3%). Un 7,4% no fueron clasificables de los que el 57,2% tuvieron complejidad alta/extrema. Entre los no-clasificables los problemas de salud mental fueron los más comunes.

ConclusionesLas herramientas del MOA a PVIH permiten clasificar y estratificar a la mayoría de los pacientes de una consulta con población no estándar. Aquellos que no encajaron en los perfiles preestablecidos generalmente presentaron un alto grado de complejidad. La creación de un perfil enfocado en la salud mental o de perfiles mixtos podría facilitar la clasificación de más pacientes.

The prognosis of HIV infection has changed dramatically since the first cases of the pandemic were reported in 1981.1–4 From being a rapidly fatal disease where care focused on the control of opportunistic infections and tumours, it has evolved into a chronic disease with a good prognosis in an increasingly older population, where the challenge is to manage follow-up and chronicity.5,6 However, care that focuses exclusively on antiretroviral therapy (ART), laboratory parameters and complementary tests can leave people living with HIV (PLHIV) feeling that the physical and psychosocial aspects of their health that matter to them are not relevant to their clinicians.7 Such care should be understood as another aspect of a set of measures that take into account the need for integrated, person-centred health care, promoting the importance of health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and providing a range of care according to individual needs,8 with the aim of ensuring that patients receive the “highest possible level of physical and mental health”9 while making efficient use of available resources.

According to the report on the HIV continuum of care in Spain,10 it is estimated that in 2021 there were between 136,436 and 162,307 PLHIV. In the same year, 2768 new infections were diagnosed,11 which, although a decrease compared to previous years, adds to the total number of infected people. This figure will continue to grow if the 95-95-95 targets proposed by UNAIDS for 2030 are not met.10 Therefore, the challenge of providing health care to an increasing number of people with a chronic disease will have to be met. According to data from the AIDS Research Network Cohort (CoRIS), for PLHIV who started ART in recent years (2014–2019) with high CD4 counts and no prior AIDS diagnosis, estimated survival is close to that of the general population, especially among men who have sex with men.12 In addition, the causes of mortality in this population have also changed from being directly related to HIV and opportunistic diseases to being mainly non-AIDS-defining neoplasms or related to patient comorbidities.13,14

This change in the care needs of the PLHIV population led to the creation of a multidisciplinary group promoted by GeSIDA [AIDS Study Group] and SEISIDA [Spanish Interdisciplinary AIDS Association] articulated in the “National Policy” project with the aim of reflecting on the ideal model of care for PLHIV. The starting point was the chronic care model, developed by Edward Wagner et al. as the main international reference model in chronic disease care.5 This framework of care promotes the adoption of evidence-based clinical recommendations, the improvement of teamwork, the inclusion of all parties involved in patient care and empowering patients to become involved in their own care. This model has been shown to have significant positive effects on chronic disease care by facilitating discharge home, as well as reducing re-admissions and healthcare costs.5 This model has been little applied in HIV,15,16 in contrast to other chronic diseases such as heart failure, diabetes mellitus, asthma and depression.17,18

In 2017, work began on developing a proposed model of care for PLHIV that would meet the new challenges arising from chronicity, improved HIV prognosis and the changing profiles of affected people. The first step was an analysis of the challenges and the overall HIV landscape in Spain19–21 as a basis for the ideal model of care for PLHIV.5 Once the model had been defined, unmet needs and areas for improvement in the healthcare and community setting were prioritised in order to propose specific improvements in the structure and processes of the continuum of care. To this end, support tools were developed to assess the degree of implementation of the model's components in healthcare centres, the complexity of the patients and a stratification system to adjust the provision of care to the care needs of the different patient profiles.22

Our objective was to apply the stratification tools by complexity and patient profile of the optimal model of care for HIV-infected patients to assess the characteristics and needs of PLHIV attending a clinic with a high proportion of migrants living in administrative insecurity. It was also assessed whether these tools were useful to adequately classify the majority of patients, as well as their potential limitations.

Material and methodsModel characteristics and applied stratification toolsThe optimal model of care for HIV-infected patients is the result of the work of a multidisciplinary group promoted by GeSIDA and SEISIDA and developed by hospital and primary care physicians, nurses, pharmacists, psychologists, social workers, health managers, community and patient organisations, with the support of the pharmaceutical industry (ViiV-Healthcare) and coordinated by a consulting expert company in the field (SI-HEALTH). All documents and tools developed in this project, which started in 2017, can be accessed and downloaded from the GeSIDA website in the patient stratification section (https://gesida-seimc.org/estratificacion-herramientas). For this study, classification by complexity and stratification by patient profile have been used.

Stratification by level of complexity classifies PLHIV into four different levels according to their score (Fig. 1)22:

- •

Extreme complexity: ≥23

- •

High complexity: >15 and <23

- •

Average complexity: >5 and ≤15

- •

Low complexity: ≤5

The variables assessed to establish degree of complexity are: pregnancy, social support, use of traditional illicit drugs, risky sexual behaviour, HIV complexity, comorbidities, psychological and cognitive status, and functional status.

Stratification by patient profile facilitates classification into seven different profiles (blue, yellow, purple, green, fuchsia, lilac and orange) according to previously defined clinical, social, demographic and behavioural variables (Fig. 2).22 Where the patient does not fit any of these profiles, he/she is labelled as “unclassifiable”.

Study populationAn observational, cross-sectional, retrospective study was conducted that included adult patients with chronic HIV infection who were being followed up by the National Referral Centre for Tropical Diseases of the Ramón y Cajal University Hospital Department of Infectious Diseases during the period from 1 January to 30 June 2023. Patients with no follow-up during the study period or with no lab test HIV follow-up (CD4+ T-lymphocyte count and HIV viral load) were excluded. Basic demographic data (age, sex and country of origin) were collected and classified according to complexity profile and patient type.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of the sample was conducted. Qualitative variables are described in terms of frequencies and percentages, and quantitative variables in terms of median and interquartile range. Standard statistical tests were used for comparison. Analysis was performed with the STATA statistical package version 18 (StataCorp. 2023. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.) applying a significance level <0.05.

Ethical aspectsAs the objective of this study was to improve quality of care, and in accordance with Spanish Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December, on the Protection of personal data and guarantee of digital rights, the Independent Ethics Committee (IEC) of our centre did not consider it necessary for the study to be assessed by an independent ethics committee when it was informed of the type of study to be conducted.

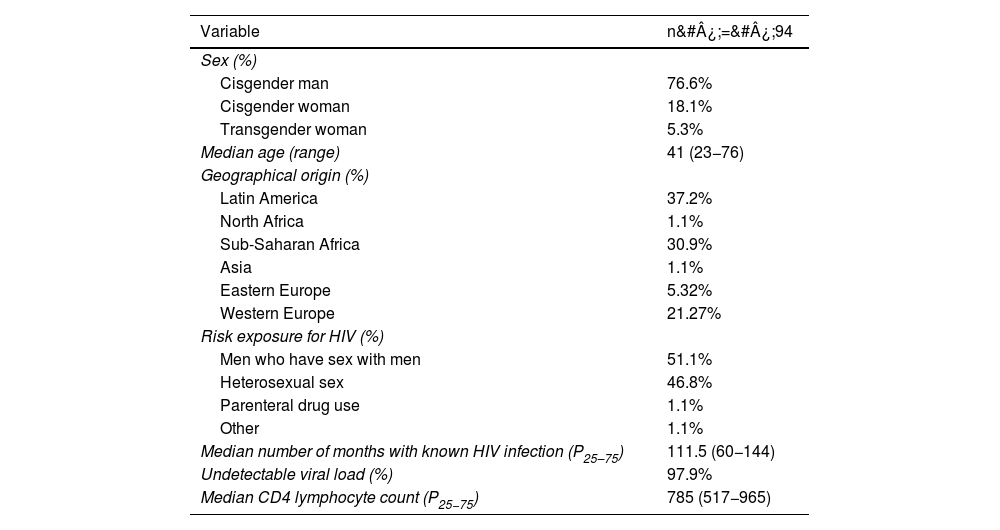

ResultsDemographic data and immunological and virological statusDuring the study period, data from 94 adult participants who met the inclusion criteria were analysed, 72 of whom were cisgender men (76.6%), 17 cisgender women (18.1%) and five transgender women (5.3%), with a median age of 41 years (minimum value of 23 and maximum of 76 years).

Some 37.2% were from Latin America, 30.9% from Sub-Saharan Africa, 26.6% from Europe, 4.3% from North Africa and 1.1% from Asia (Table 1). The most common countries of origin were Bolivia (3.19%), Cameroon (6.38%), Colombia (4.26%), Côte d'Ivoire (2.13%), Dominican Republic (2.13%), Equatorial Guinea (6.38%), Guinea Bissau (4.26%), Jamaica (2.13%), Morocco (3.19%), Nigeria (2.13%), Peru (2.13%), Russia (2.13%), Sierra Leone (3.19%), Spain (20.21%), Ukraine (2.13%) and Venezuela (18.09%).

Sociodemographic characteristics.

| Variable | n&#¿;=&#¿;94 |

|---|---|

| Sex (%) | |

| Cisgender man | 76.6% |

| Cisgender woman | 18.1% |

| Transgender woman | 5.3% |

| Median age (range) | 41 (23−76) |

| Geographical origin (%) | |

| Latin America | 37.2% |

| North Africa | 1.1% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 30.9% |

| Asia | 1.1% |

| Eastern Europe | 5.32% |

| Western Europe | 21.27% |

| Risk exposure for HIV (%) | |

| Men who have sex with men | 51.1% |

| Heterosexual sex | 46.8% |

| Parenteral drug use | 1.1% |

| Other | 1.1% |

| Median number of months with known HIV infection (P25–75) | 111.5 (60−144) |

| Undetectable viral load (%) | 97.9% |

| Median CD4 lymphocyte count (P25−75) | 785 (517−965) |

A total of 92 participants (97.9%) had an undetectable viral load. The other two had viral loads of 2.9 and 3.8 log. The median CD4 lymphocyte count was 785&#¿;cells/mm3 (p25–75 517−965) with a minimum of 170 cells/mm3 and a maximum of 1623&#¿;cells/mm3. The median number of months with known HIV infection was 111.5 (p25–75 60−144).

A total of 92 participants had sexual exposure to HIV risk; 48 cases (51.1%) were men who have sex with men and 44 cases (46.8%) were heterosexual sex. There was one case of acquisition through intravenous drug use and one case where transmission is believed to have occurred in the country of origin (Algeria) through blood donation or sharing of razor blades.

Stratification by profile and complexityIn total, 74 patients (78.7%) had low complexity, 11 medium (11.7%), one high (1.0%) and eight extreme (8.5%) with a median score of 0, 14, 20 and 28 points, respectively. Of the 74 patients classified as “low complexity”, 40 of them had 0 points, i.e., they had no characteristics specifically indicative of complexity. The main causes contributing to extreme complexity were substance use with physical or psychological dependence, risky sexual behaviour (risky practices or chemsex) and lack of social support.

In the classification by profile, blue was the most common (61 cases; 64.9%), followed by lilac (11 cases; 11.7%), purple (six cases; 6.3%) and green (four cases; 4.26%) (Fig. 3). Seven participants were unclassifiable (7.5%), with a mean complexity of 18 points, three of them belonging to the extreme complexity group and one to the high complexity group. The main contributors to this complexity were chemsex, active substance use and a detectable viral load (in the context of such use) and, to a lesser extent, the absence of social support and mental disorder.

DiscussionThe changing nature of HIV infection and its transformation into a chronic disease requires a new care framework, focused on the needs of PLHIV today. The chronic care model developed for PLHIV and analysed in this study would respond to these challenges. It is a comprehensive, person-centred model that has been developed with all parties involved in the continuum of care, including the patients themselves. The classification of PLHIV according to their complexity facilitates the identification of patients with the greatest needs, matching the level of care and the most specialised resources while improving the efficiency of health and social organisations. In addition, stratification into profiles means that care tailored to the specific needs of each patient can be offered. Through this model, care is personalised and variability is reduced, promoting greater equity in care regardless of the professional or geographical setting in which it is provided.

In our study, the majority of participants were cisgender, migrant, middle-aged men with few years of known HIV infection. This would explain why a very high proportion have a blue-type profile, associated with low complexity, good adherence to follow-up and few comorbidities. The majority of migrants are young people of working age who move in search of work or better living conditions. The gender distribution in this population is balanced, although it has shifted from male predominance (53% in 2009) to female predominance (51% in 2018) in recent years.23 However, HIV infection remains highly male-dominated, so the predominance of males observed in the study is to be expected. In addition, most HIV infections among migrants occur in host countries, where the population of men who have sex with men is much more exposed.24,25 However, it is striking that the green profile does not predominate in this population, characterised fundamentally by problems of social integration and adaptation, which is more to be expected in people who may be living in administrative insecurity. It is likely that incorporation into the health system due to their HIV status and the high proportion of Latin Americans (with more support networks in Spain and fewer linguistic and cultural differences) has favoured this integration. The overall immunological and virological control of the participants was very good.

There were only two participants with detectable HIV viral load: one case due to temporary withdrawal of antiretroviral therapy and subsequent control of viral replication (because she did not believe she was infected with HIV), and a second case associated with poor adherence in the context of active drug use and chemsex with lack of social support. This high response rate, in a population that often faces administrative, cultural and language barriers, is probably due to the model of care that includes the involvement of an NGO integrated into the Department of Infectious Diseases (Salud entre Culturas [Health Across Cultures]; www.saludentreculturas.es). Its functions include the provision of mediators-interpreters for consultations (its own and those of other specialities), accompaniment and counselling in the hospital, management of social support, educational programmes and coordination with cross-cultural psychology consultation services.

The application of the stratification tool has allowed us to classify the majority of patients from a highly vulnerable population in a single consultation. It is simple to use, takes only a few minutes per person and can be automated in electronic health record systems. However, seven (7.4%) of the participants were “unclassifiable”. These patients often presented with mental health problems that were not serious but that required psychological care (an assumption not covered by the tool). The most common was anxiety or depression associated with HIV stigma, hate crimes as a result of sexual orientation or gender identity, and post-traumatic stress disorder. In addition, four unclassified individuals (57.2%) had a high or extreme level of complexity, highlighting the particular importance of this group.

In Spain, results of the implementation of the stratification and complexity model for PLHIV have been reported in other studies, revealing the particular characteristics of the populations treated. One example is the study conducted by Giménez-Arufe and Mena in Galicia (n&#¿;=&#¿;1424),26 with a predominance of people of European origin living with HIV for more than 10 years and a mean age older than in our cohort (43&#¿;±&#¿;11 years). In their study, the blue profile was predominant, although in a lower proportion (35%) than in ours, and the authors observed a notable increase in yellow and green profiles, with 40% of participants classified as highly or extremely complex. For the lilac and purple profiles, the percentages were similar to those in our study. Interestingly, in their sample, 16.7% of the participants were not classifiable by the tool, of which 70.8% showed extreme complexity. In contrast, the study by Von Wichmann et al. (n&#¿;=&#¿;273)27 identified a predominance of the yellow profile (42.7%), a higher mean age (53 years), a polypharmacy incidence of 30%, as well as a history of infection of more than 20 years on average, compared to our study, indicative of an older population with more comorbidities, which probably implies greater complexity and resource consumption.

Another aspect to be taken into account is that the application of this model can be complemented by the quality indicators developed by GeSIDA,28 which constitute the minimum standards of care to be met in HIV care units.

The main limitations of our study are the limited number of participants and its cross-sectional design, which shows a static picture of the patients seen and does not allow for changes during follow-up. Serial cut-offs would be a good strategy to understand the main changes and trends in this population. On the other hand, the typology of the people cared for in the study is very specific and may be difficult to compare with other centres. However, the low number of unclassifiable patients shows the flexibility of the model.

The current tool can be used to stratify the vast majority of patients from very diverse populations. However, the group of unclassifiable persons (9.5%–16.5%), although not very high, is usually associated with a high or very high degree of complexity (57.2%–70.8% of cases), which makes it a group worthy of special attention. The inability to classify patients with high to extreme complexity can negatively affect their well-being by not providing them with the specific care they need. Most of the unclassifiable persons had problems related to mental health. If this situation is repeated in other studies or in the implementation of the tool in healthcare practice, the development and validation of new or mixed profiles may be necessary.

Identifying the degree of complexity and stratification of patients is crucial in order to tailor care to their specific needs, optimise the use of resources and efficiently adapt the demand for care. This would help to avoid overburdening health services, facilitate management and accountability based on the complexity and costs associated with each patient, and incorporate concrete measures tailored to population groups according to their needs. In addition, classifying patients by profile facilitates and promotes targeted intervention, standardisation of care for each group, equity and collaborative management between all parties involved in the continuum of care.

FundingThis study has received no funding from any public or private entity.

Conflicts of interestJAPM, CA and SM were involved in developing the optimal model of care for HIV-infected patients. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.