The WHO proposed to achieve hepatitis B virus (HBV) elimination by 2030, but this goal is very difficult to attain. People living with HIV (PLWH) may represent a subset where microelimination can be reached sooner. This study aimed to assess the incidence of HBV infections and changes in the prevalence of active HBV infection among PLWH in Spain.

MethodsA prospective cohort study, including all PLWH attending a university hospital in Southern Spain from January 2011 to December 2022, was conducted. Serum HBV markers (HBsAg, anti-HBs, anti-HBc) were tested at baseline and at least yearly afterwards. Incident cases were identified by anti-HBc seroconversion.

ResultsNine hundred and eighty PLWH were included. At the beginning of the study, 26 (2.7% [95% CI: 1.7–3.8%]) tested positive for HBsAg, 428 (43.7% [95% CI: 42.8–49.4%]) for anti-HBc and 386 (39.4% [95% CI: 39.8–46.3%]) for anti-HBs. After a median (Q1–Q3) follow-up of 115 (35–143) months, two new infections were documented, yielding an incidence rate of 2.24 (95% CI: 0.27–8.1)/100,000 person-years. The prevalence of active HBV infection declined from 3.4% [95% CI: 2.0–5.0%] in 2011 to 2% [95% CI: 1.0–3.0%] in 2022 (p for linear trend=0.027). At the end of the study, 167 (24%) PLWH still were susceptible to HBV.

ConclusionsThe incidence of HBV infection among PLWH in Spain is close to the WHO target. The prevalence of active HBV infection has decreased substantially during the last 12 years. These data suggest that micro-elimination of HBV/HIV infection is on the track in Spain.

La OMS propuso la eliminación del virus de la hepatitis B (VHB) en 2030. Las personas que viven con VIH (PVVIH) pueden representar un subgrupo en el que la microeliminación podría alcanzarse antes. Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar la incidencia de infecciones por VHB y los cambios de prevalencia de la infección activa por VHB entre las PVVIH en España.

MétodosEstudio de cohorte prospectivo, incluyendo a todas las PVVIH atendidas en un hospital universitario en el sur de España desde enero de 2011 hasta diciembre de 2022. Se analizaron los marcadores séricos de VHB (HBsAg, anti-HBs, anti-HBc) al inicio y al menos anualmente.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 980 PVVIH. A la entrada en el estudio, 26 (2,7% [IC95%: 1,7-3,8%]) dieron positivo para HBsAg, 428 (43,7% [IC95%: 42,8-49,4%]) para anti-HBc y 386 (39,4% [IC95%: 39,8-46,3%]) para anti-HBs. Tras un seguimiento mediano (Q1-Q3) de 115 (35-143) meses, documentamos dos nuevas infecciones (tasa de incidencia de 2,24 [IC95%: 0,27-8,1]/100.000 personas-año). La prevalencia de la infección activa por VHB disminuyó del 3,4% [IC95%: 2,0-5,0%] en 2011 al 2% [IC95%: 1,0-3,0%] en 2022 (p para tendencia lineal=0,027). Al finalizar el estudio, 167 (24%) PVVIH seguían siendo susceptibles al VHB.

ConclusionesLa incidencia de infección por VHB entre las PVVIH en España se aproxima al objetivo de la OMS. La prevalencia de la infección activa por VHB ha disminuido sustancialmente en los últimos 12años. Estos datos sugieren que la microeliminación de la coinfección VHB/VIH está próxima en España.

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a major public health concern, causing 820,000 deaths worldwide due to cirrhosis and hepatocarcinoma.1 The estimated global prevalence of chronic HBV infection is 3.61%.2 In 2016, the WHO proposed to achieve elimination of viral hepatitis by 2030.3 Elimination indicators for HBV infection include reaching a yearly incidence of new cases of 11 per 100,000 by 2025 and, finally, a goal of 2 per 100,000 by 2030.4 HBV elimination would require diagnosis of most active infections, treatment of diagnosed cases and, mainly, widespread vaccination of susceptible people. However, unfortunately, large-scale vaccination programs are not currently being implemented worldwide.4 Barriers to universal vaccination include vaccine availability, costs, lack of awareness of the benefits of the vaccine and vaccine hesitancy.5,6 The WHO target will likely be therefore difficult to attain. Presently, data on the progress of HBV elimination are limited, primarily relying on modeling studies.7

The worldwide prevalence of HBV infection among people living with HIV (PLWH) is estimated to be 7.6%.8 However, several features of PLWH suggest that HBV micro-elimination could be easier to obtain in such a population9: (i) PLWH undergo closer clinical monitoring than the general population, so that a higher proportion of PLWH has a diagnosis of HBV serostatus; (ii) there are recommendations from many health services for vaccination of PLWH against HBV10; (iii) certain antiretroviral drugs, such as tenofovir (TFV),11 emtricitabine (FTC)12 and lamivudine (3TC),13 possess anti-HBV activity and may confer protection against incident HBV infections in PLWH.14 For the above-stated reasons, PLWH may represent a unique opportunity for exploring HBV microelimination evolution. However, again, data on how the incidence of HBV infection among PLWH is evolving along the world are very scarce.

Our aim was to assess the incidence of new cases of HBV infection among PLWH in Spain, as well as to appraise changes in the serial prevalence of active infection in this population.

MethodsPatients and designAll PLWH attending the Infectious Diseases Unit of a tertiary-care university hospital in Southern Spain from January 2011 to December 2022 were included in this prospective cohort study. PLWH are seen at least every six months. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) was given according to the recommendations from the GeSIDA Spanish Group.15 According to these recommendations, all HIV/HBV-coinfected patients should be treated with ART combinations including TFV plus FTC or 3TC. In addition, all PLWH are recommended to undergo HBV screening. Serum HBV markers (HBsAg, anti-HBs, anti-HBc) were tested at baseline and at least yearly afterwards. HBV vaccination was offered to susceptible patients according to the criteria of the attending physician until 2019. Since January 2020, HBV vaccination was routinely recommended to all susceptible patients at each visit. For HBV vaccination, patients were referred to specific vaccine delivery units. Data were collected from May to October 2023.

Definition criteriaActive HBV infection was diagnosed when serum HBsAg turned out to be positive. A new HBV infection was diagnosed when anti-HBc seroconversion was documented. PLWH who tested positive for anti-HBc were classified as exposed, while those who were negative for both anti-HBs and anti-HBc were categorized as susceptible. Subjects bearing anti-HBs without anti-HBc were considered to show a prior vaccination profile.

Determination of HBV infection serum markersHBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc were tested by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay Elecsys®, using commercially available equipments (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany).

Data analysisThe primary variable of the study was the development of a new HBV infection. The secondary variable was active HBV infection. The incidence of new HBV infections was calculated as the number of patients showing anti-HBc seroconversion divided by the number of patient-years at risk, i.e. the time in follow-up of those who were seronegative for anti-HBc. Likewise, the serial prevalence of active HBV at each year of the study was estimated.

Categorical variables are expressed as numbers (percentage) and continuous variables as median (quartile 1–quartile 3 [Q1–Q3]). 95% confidence intervals (CI) are provided for the main rates. Frequencies were compared by the Chi-square test for linear trend and continuous variables by the Friedman test. Factors associated with HBV exposure in the univariate analysis with a p-value ≤0.1, along with age and sex, were entered into a binary logistic regression model. These analyses were carried out using the IBM SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL, USA) and the Stata 16.1 Statistics/Data Analysis (StataCorp College Station, TX, USA) packages.

EthicsThe study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme. All PLWH gave their written informed consent before enrollment. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

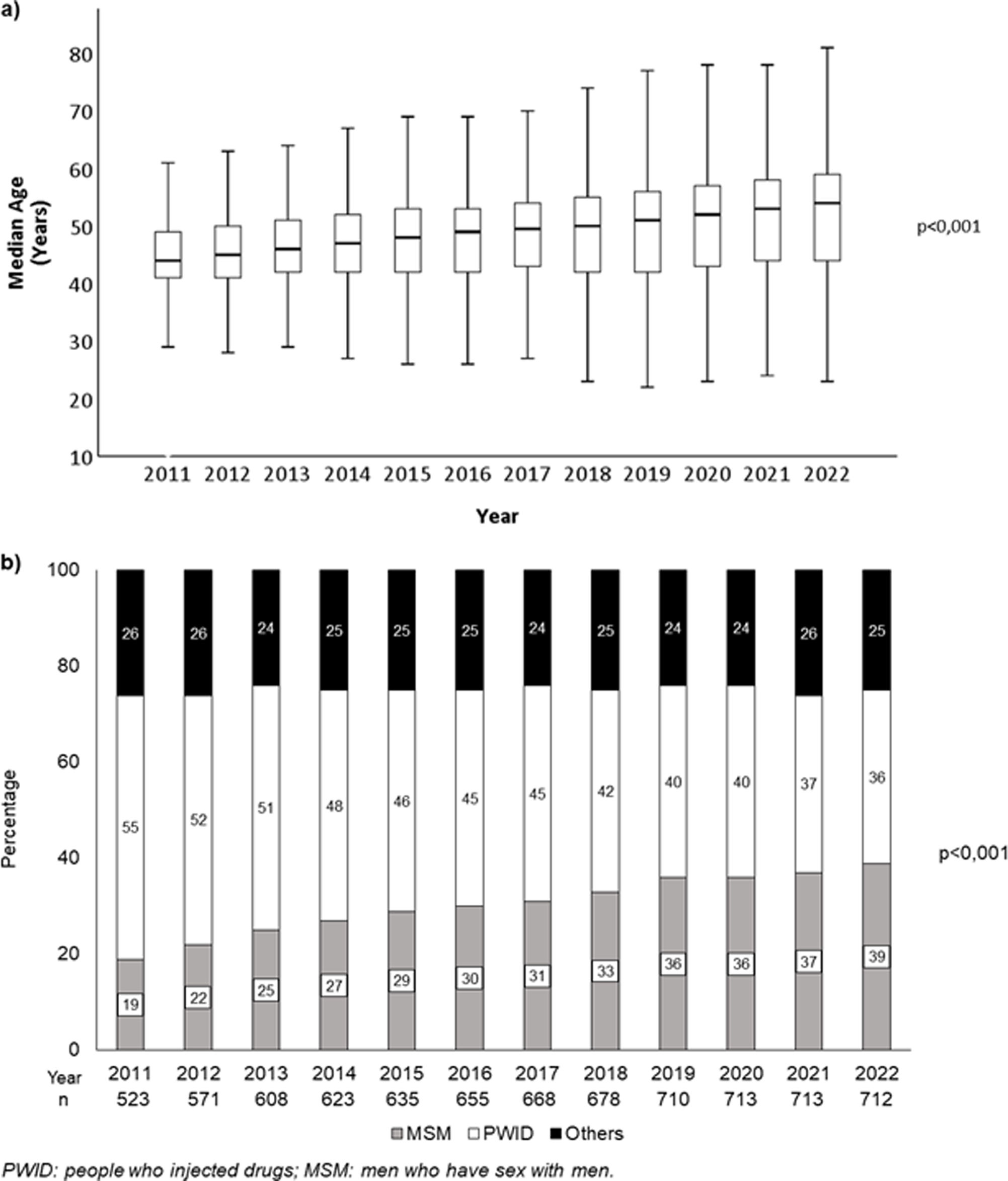

ResultsCharacteristics of the populationNine hundred and eighty PLWH were included in the study. Among patients included in 2011, 483 (92.4%) were receiving ART, as were 524 (91.8%) participants in 2012 and 574 (94.4%) of those analyzed in 2013. From 2014 onwards, according to the Spanish national guidelines,16 all patients were prescribed ART. The characteristics of the population are described in Table 1. The age and the route of HIV infection of the patients analyzed each year during the study are depicted in Fig. 1. The median follow-up was 115 (35–143) months. Fifty-nine (6%) PLWH died and 189 (19.3%) were lost to follow-up during the study period.

Characteristics of the population (n=980).

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Male sex, n (%) | 784 (80.0) |

| Baseline age, years* | 44 (38–50) |

| Country of birth Spain, n (%) | 919 (94.2) |

| Route of HIV infection, n (%) | |

| - PWID | 433 (44.2) |

| - MSM | 313 (31.9) |

| - Others | 234 (23.9) |

| HBV markers at joining the study, n (%) | |

| - Positive HBsAg | 26 (2.7) |

| - Positive anti-HBs | 386 (39.4) |

| - Positive anti-HBc | 428 (43.7) |

| - Positive anti-HBc/negative anti-HBs | 187 (19.1) |

| - Positive anti-HBs/negative anti-HBc | 186 (19.0) |

| - Negative anti-HBs/negative anti-HBc | 300 (30.6) |

| Exposure to ART during the follow-up, n (%) | |

| - TFV | 750 (77.0) |

| - 3TC/FTC | 910 (93.0) |

PWID: people who injected drugs; MSM: men who have sex with men; ART: antiretroviral treatment; TFV: tenofovir; 3TC: lamivudine; FTC: emtricitabine.

When patients joined the study, 26 (2.7% [95% CI: 1.7–3.8%]) patients tested positive for HBsAg, 428 (43.7% [95% CI: 42.8–49.4%]) for anti-HBc and 386 (39.4% [95% CI: 39.8–46.3%]) for anti-HBs. The presence of anti-HBc, i.e., that of previous HBV exposure, was associated with older age and with having acquired HIV through intravenous drug use (Table 2).

Basal factors associated with HBV exposure (n=980).

| Characteristic | Anti-HBc positive, n (%) | OR univariate(95% CI) | punivariate | Adjusted OR(95% CI) | pmultivariate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | 1.8 (1.3–2.6) | <0.001 | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | 0.168 | |

| - Male | 364 (49.1) | ||||

| - Female | 64 (34.6) | ||||

| Age, n (%) | 4.3 (3.2–5.7) | <0.001 | 3.1 (2.2–4.5) | <0.001 | |

| - <44 years | 117 (27.5) | ||||

| - ≥44 years | 311 (62.1) | ||||

| Country of birth, n (%) | 1 (0.6–1.7) | 0.994 | |||

| - Spain | 402 (46.2) | ||||

| - Elsewhere | 24 (46.2) | ||||

| Route of infection, n (%) | |||||

| - PWID | 295 (73.6) | Reference | Reference | ||

| - MSM | 86 (28.1) | 0.1 (0.1–0.2) | <0.001 | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | <0.001 |

| - Others | 47 (21.5) | 0.1 (0.1–0.1) | 0.1 (0.1–0.2) | ||

PWID: people who injected drugs; MSM: men who have sex with men.

Anti-HBc seroconversion was documented in two PLWH during the follow-up. This figure yields an incidence rate of HBV infections of 2.24 (95% CI: 0.27–8.1)/100,000 person-years. Both were men. One of them was a man who has sex with men (MSM) and the other was an injecting drug user. The first seroconversion case occurred in 2011 and the second one in 2014. None of these patients had previously been vaccinated. One of them was on darunavir/ritonavir plus etravirine therapy. The other was on TFV plus FTC plus nevirapine, but his adherence was not optimal, because he missed doses with some frequency.

Changes in HBV markers by yearsThe prevalence of active HBV infection fell from 3.4% (95% CI: 2.0–5.0%] in 2011 to 2% (95% CI: 1.0–3.0%] in 2022 (p for linear trend=0.027) (Fig. 2). Figures observed each year during the study period are shown in Fig. 2.

Two hundred and fifty-two (52%) individuals showed prior HBV exposure in 2011, versus 298 (43.1%) in 2022. The corresponding figures for subjects with prior vaccination profile and susceptible individuals were, respectively, 75 (15%) and 158 (33%) in 2011 and 227 (33%) and 167 (24%) (p<0.001) (Fig. 3). Of 205 PLHIV susceptible at the time of data closure, 119 (58.0%) received at least one vaccine dose, but we do not have data on how many received the full vaccination regimen.

Among the participants in 2011, 36 (38%) MSM had been previously exposed to HBV, 30 (31%) showed a serological profile of prior vaccination and 29 (31%) were susceptible to HBV infection. In 2022, these figures were 73 (27%), 136 (50%) and 62 (23%), respectively (p<0.001) (Fig. 4a). Among people who injected drugs (PWID) analyzed in 2011, 193 (73%) had been formerly exposed to HBV, 13 (5%) showed a vaccination profile and 59 (22%) were susceptible. In 2022, the number of exposed PWID was 189 (74%), that of with vaccination profile had increased to 27 (11%) and 38 (15%) remained susceptible to HBV infection (p=0.029) (Fig. 4b).

DiscussionThis study shows that the current incidence of HBV infection among PLWH in Spain is low, falling below the WHO-proposed milestone for 2025 and nearing the target for 2030. Accordingly, the prevalence of active HBV infection has notably decreased during the last 12 years, and no new HBV infection case was observed during the final eight years of the study. These data point out that microelimination of HBV infection in PLWH is progressing effectively in our country.

The low incidence of new cases and the declining prevalence of active HBV infection observed in PLWH herein can be attributed to, at least, three facts: (i) the widespread use of ART active against HBV in this population. Previous studies have demonstrated that this therapy protects against the occurrence of denovo HBV infection17; (ii) an increasing proportion of patients are protected by the HBV vaccine. This fact has been associated with a decline in both the incidence and prevalence of HBV coinfection among PLWH in other countries18; (iii) a decreasing proportion of PWID, who are at a higher risk of exposure to HBV than other PLWH, observed throughout the study period.

These results align with findings from other PLWH populations in Spain. For instance, a serial prevalence study conducted in another cohort of PLWH in Spain reported a decrease in the proportion of HIV/HBV-coinfected patients from 4.9% in 2002 to 3.2% in 2018.19 Likewise, another Spanish study reported that the incidence of acute hepatitis B was low and had progressively declined from 2000 to 2018.20 Similar results to those observed in this study have also been found in Germany.18

Despite a proactive referral campaign for HBV vaccination in all eligible patients, particularly during the later years of the study, a quarter of the PLWH in this cohort remained susceptible to this infection at the end of the follow-up period. This fact is a consequence of, at least, two reasons: (i) PLWH exhibit a poorer response to the hepatitis B vaccine compared to the general population,21 particularly those with less than 350 CD4/mm3.22 Schedules specifically recommended for PLWH,23 such as double-dose or four-dose vaccination schemes, yield a better response than standard schedules,24 but still worse than that observed in the general population. With regards to this issue, Heplisav-B® vaccine, a recombinant vaccine, has been shown to confer protection to non-immunized PLWH25 and PLWH who did not respond to standard vaccination regimens.26 Further and wider studies with this vaccine are required, but if these results are confirmed, this vaccine could significantly reduce the rate of PLWH without immunization. Furthermore, PLWH experience a more rapid waning immunity than those without HIV21; (ii) programs based on referral to vaccine delivery units other than those providing care to PLWH, as the one used in this cohort, yield suboptimal results.27 Despite the low incidence of HBV infection and the declining prevalence of active infection observed in our area, achieving the final goal of microelimination will likely require a much lower proportion of susceptible individuals. To this end, new vaccination strategies and programs aimed at achieving better linkage to vaccination schedules must be developed while also advancing the research of novel vaccines with improved efficacy.

In PLWH in developed countries, several circumstances may lead to earlier microelimination of HBV infection than in other subsets. Thus, HBV screening is usually recommended28 and conducted in all patients. In addition, active drugs against HBV are very commonly given as a part of many recommended ART combinations.28 Moreover, vaccination of susceptible PLWH is also generally advised.28 However, all these actions could not be sufficient to achieve the WHO microelimination goals. In fact, in a study carried out in Taiwan in PLWH who had undergone neonatal HBV vaccination and were on ART containing drugs with anti-HBV activity, an incidence of new infections much higher than the WHO target was observed.29 This fact could be explained by a significant rate of waning immunity,29 which could have been lower in our patients. Indeed, neonatal HBV vaccination started in Spain at the beginning of the 1990s, and most of our patients were born before. Because of this, they received the vaccine later in their lives, and the likelihood of loss of immune protection could have been lower than in the study mentioned above. In any case, achieving HBV microelimination will require not only the extension of immune protection through vaccination but also the periodic monitoring of serum anti-HBs levels with boosting doses for those who lose this marker. Moreover, in patients without immune protection, ART including drugs active against HBV should be prioritized over nucleoside-free regimens. The currently available HIV drug armamentarium and the drug pipeline include regimens that lack activity against HBV. These include oral drugs or combinations, as dolutegravir/rilpivirine or islatravir, as well as long-acting injectable antiretroviral drugs such, such as cabotegravir/raltegravir or lenacapavir. Investigational therapies, including immunotherapies and broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies, also show no activity against HBV. Therefore, it is essential to personalize antiretroviral treatment taking into account the activity of HBV-targeted therapies. In fact, the report of acute HBV hepatitis cases in PLWH who were switched to non-HBV protective ARV regimens30 supports this statement.

Our study has some limitations, notably being a single-center analysis, which could avoid the generalizability of the results to other areas. However, the management of PLWH does not substantially differ across Spain and Western Europe, generally followings common national and European guidelines.15,28 Accordingly, as stated above, results consistent with those reported here have been found in other studies in our country,20 as happened in other European nations.18 Because of this, data like these are expected to be found in the Western European area. However, the landscape of HIV/HBV is likely to be very different in other areas, particularly in developing countries. Thus, surveys like this are warranted in other areas. A second limitation is the unavailability of an accurate history of HBV vaccination from all included patients. Consequently, we had to define the prior vaccination profile based on the presence of isolated anti-HBs. In any case, to our knowledge, this is the first analysis of the incidence of HIV/HBV coinfection performed in a large cohort with a follow-up exceeding 10 years. This constitutes the main strength of the present study.

In summary, the incidence of HBV infection among PLWH on ART is very low in Spain and the prevalence of active infections is significantly decreasing, which suggest that microelimination can be reached by the WHO-proposed timeline. However, a substantial proportion of patients remain susceptible to HBV infection. Therefore, efforts to expand HBV immunization among PLWH, as well as to keep the immune status in the long term, must be carried out to definitively eliminate HIV/HBV coinfection.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMS and JAP performed the study protocol. MS, JMC, ACG, CMS, MPG, PRM performed data collection. MS wrote the manuscript and produced the tables and figures. CMS conducted a comprehensive review of the English language. LMR, JAP and JM were responsible for revision of the manuscript. JAP supervised the entire process.

FundingThis study has been funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III through the project “PI018/00606” (co-funded by European Regional Development Fund/European Social Fund “A way to make Europe”/“Investing in your future”). CMS is supported by CIBER “Consorcio de Investigación Biomédica en Red” (reference CB21/13/00118), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovavión y Unión Europea – NextgenerationEU. ACG has received a research extension grant from Acciones para el refuerzo con recursos humanos de la actividad investigadora en las Unidades Clínicas del Servicio Andaluz de Salud 2021, acción B (Clínico-Investigadores) (grant number B-0061-2021). She has also received a Juan Rodés grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (grant number JR23/00066). MS has received a Río Hortega grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (grant number CM21/00263). JMC has received a Rio Hortega grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (grant number CM23/00255).

Conflict of interestsNone of the authors have a conflict of interest for this study.

We would like to thank all patients who are always ready to participate in studies so that we can continue to contribute to scientific knowledge. We thank all those who participated in the preparation of this manuscript. Learning from the experience of senior researchers and teamwork are the key to success.