Aspergillosis is a disease caused by the widely distributed fungus Aspergillus spp. Conidia are airborne and in the host can cause mild local infections, such as rhinosinusitis, to invasive fungal infection (IFI).1 The invasive form is rare, but has a mortality rate of over 50%.1 It mainly affects immunosuppressed patients (prolonged neutropenia, haematopoietic cell or solid organ transplant recipients, AIDS) or those on treatment with corticosteroids.2,3

We present the case of a 73-year-old male with a history of liver cirrhosis due to haemochromatosis, who developed invasive aspergillosis with pulmonary and cerebral involvement after treatment with high doses of corticosteroids.

One month earlier, during a hospital admission for hydropic decompensation and pneumonia, the patient developed renal failure, interpreted as a possible flare-up of IgA nephropathy or post-infectious glomerulonephritis. Due to thrombocytopenia secondary to his liver disease, we decided not to perform a renal biopsy and treat him with prednisone at doses mg/kg/day a week (80mg/day), with a progressive reduction of 10mg every three weeks. This time he was admitted again due to oedema-ascites decompensation. After evacuation paracentesis, treatment with piperacillin-tazobactam was started for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Five days later, he developed respiratory failure and radiological images compatible with pneumonia. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Aspergillus fumigatus were isolated in his sputum, so oral isavuconazole was added to the treatment. Four days later, the patient was found to have a left pleural effusion compatible with empyema, requiring drainage.

The patient suddenly developed left hemiparesis. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a nodular lesion in the right thalamus with ring enhancement. Given the high suspicion of cerebral aspergillosis, we replaced isavuconazole with voriconazole due to its greater diffusion to the central nervous system (CNS).4

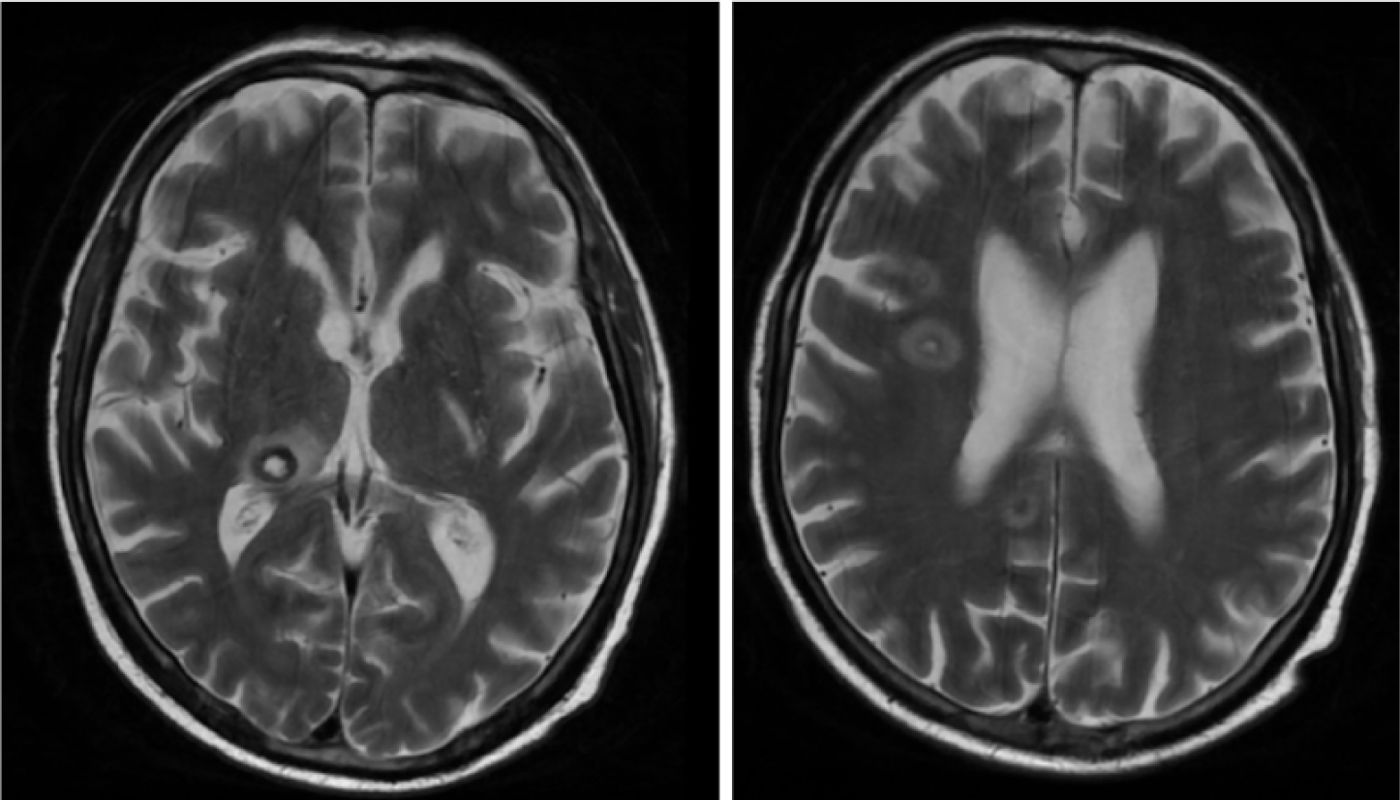

Plasma galactomannan and PCR for Aspergillus spp. in blood and pleural fluid were positive, and A. fumigatus was isolated from pleural fluid culture. In addition, brain MRI (Fig. 1) and chest CT confirmed invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with CNS involvement. We ruled out endophthalmitis, as well as endocarditis (echocardiogram and negative blood cultures). Due to poor clinical progress, and to control the primary focus of the infection without increasing nephrotoxicity, we added inhaled liposomal amphotericin B. Despite the treatment, the patient progressively deteriorated, and eventually died two weeks after being diagnosed.

Aspergillus spp. is a ubiquitous fungus. More than 70% of infections are caused by A. fumigatus due to its greater pathogenicity.5 Pulmonary aspergillosis is the most common, with haematogenous dissemination in 10% of patients. CNS involvement is rare, but has a high mortality rate.1,5

The definitive diagnosis of IFI requires microbiological and/or histopathological verification. IFI will be likely if the individual has a predisposing factor, characteristic clinical/radiological and microbiological evidence (culture, galactomannan and/or positive Aspergillus spp. PCR.3,6 Beta-d-glucan is not included as a criterion due to its low specificity.7

In our case, we considered cirrhosis, renal failure, and treatment with corticosteroids as risk factors; we ruled out haemochromatosis because, although the relationship between iron overload and the risk of fungal infection is known, iron levels were normal.8 The manifestations were cavitary lung lesions and focal brain lesions, which we confirmed with positive culture, PCR and galactomannan in blood and pleural fluid.6

The treatment of choice for IFI is a triazole. Voriconazole has traditionally been used as first-line therapy, although subsequent studies have demonstrated the non-inferiority of isavuconazole, which, unlike voriconazole, does not require level monitoring. Posaconazole, although more often used for prophylaxis, is an alternative option.1,3,9

For patients who have received IFI prophylaxis with azoles or who have a contraindication to them, liposomal amphotericin B is used.1,2 Echinocandins can be used as rescue therapy.2,7

The duration of treatment is 6–12 weeks, personalised according to progress.3,5

The standard treatment for CNS aspergillosis is voriconazole. Surgical resection increases survival but was ruled out in our patient due to his clinical situation and comorbidities.3,7,9 Corticosteroids should be avoided as a treatment for cerebral oedema due to the cellular immunodeficiency they induce.3,10

In conclusion, it is important to remember that treatment with corticosteroids is a major risk factor for the development of invasive aspergillosis, a disease with high morbidity and mortality rates.