The specialty of Microbiology and Parasitology is a four-year multidisciplinary training with a central role in the diagnosis and epidemiological surveillance of infectious diseases.

The aim of this study is to analyze the degree of implementation of the official program and the degree of satisfaction of residents with their training.

MethodsWe conducted an online survey distributed in eight sections to which active residents of the Specialty of Clinical Microbiology and Parasitology had access.

ResultsA total of 69 responses were received, with a predominance of residents from the regions of Madrid (43.5%) and of FIR admission route (55%).

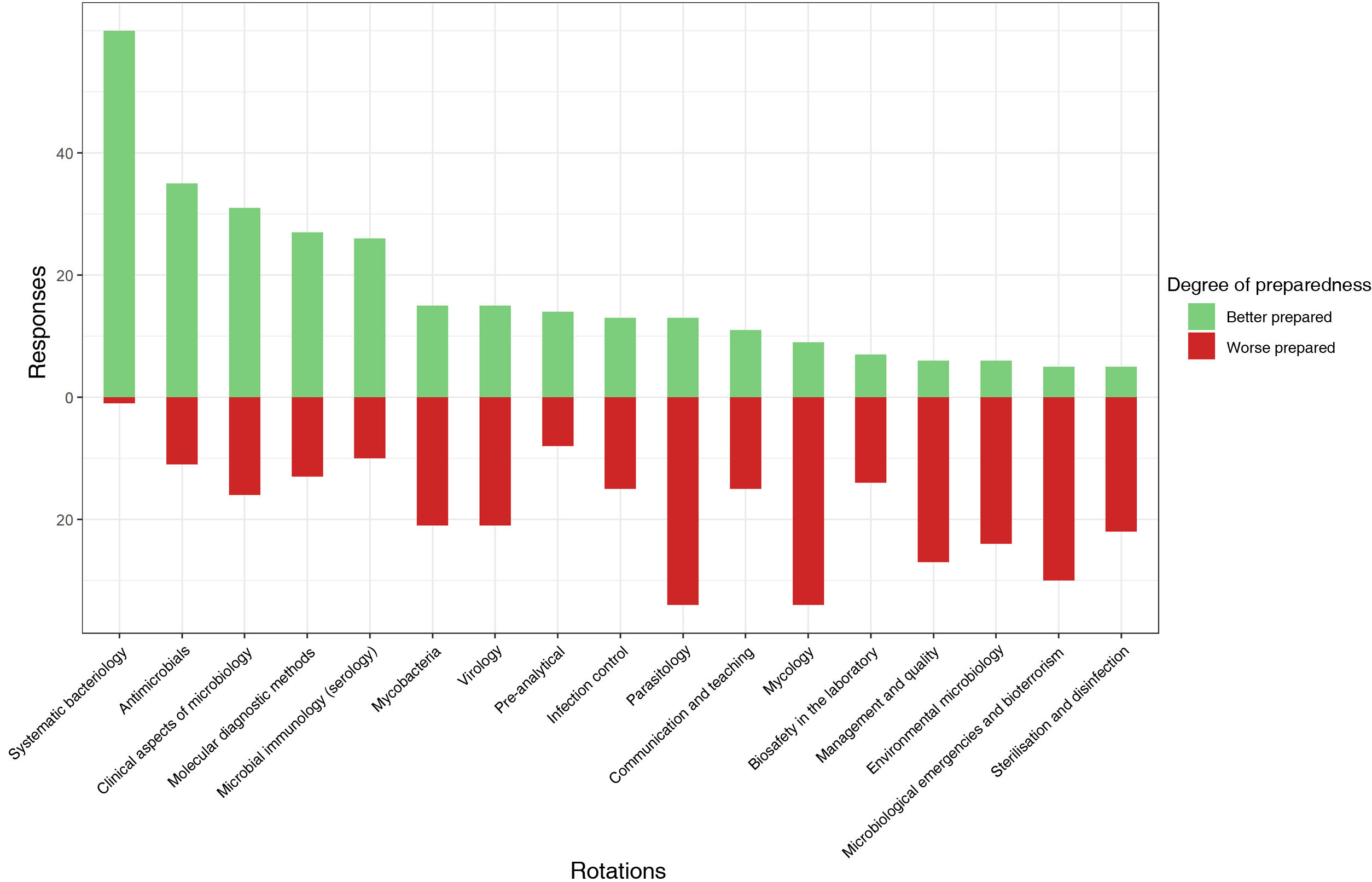

The areas in which the residents feel best prepared correspond to systematic bacteriology, antimicrobials and clinical aspects of microbiology. The areas with the worst preparation, on the other hand, are mycology, parasitology and microbiological emergencies.

There are significant differences between the clinical rotation time for residents with MIR access pathway with respect to residents with other degrees.

Respondents perceive a high degree of responsibility and a medium agreement with the quality of teaching. Attendance at clinical sessions and external rotations is frequent.

Research activity is perceived as complicated, both at the level of doctoral studies and with respect to entering research lines and the publication of scientific results.

ConclusionSome points of improvement of the training itinerary have been identified that need to be reinforced. Likewise, it would be interesting to seek a better balance between care, teaching and research activities.

La especialidad de Microbiología y Parasitología es una especialidad multidisciplinar de cuatro años con un papel central en el diagnóstico y la vigilancia epidemiológica de las enfermedades infecciosas.

Con este trabajo se pretende analizar el grado de aplicación del programa formativo oficial y el grado de satisfacción de los residentes con su formación.

MétodosSe realizó una encuesta online distribuida en ocho secciones a la que tuvieron acceso los residentes en activo de la Especialidad de Microbiología y Parasitología Clínicas.

ResultadosSe recibieron 69 respuestas, con predominio de residentes de la Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid (43,5%) y de vía de origen FIR (55%).

Las áreas en las que nos residentes se sienten mejor preparados corresponden a bacteriología sistemática, antimicrobianos y aspectos clínicos de la microbiología. Las áreas de peor preparación, por el contrario, son micología, parasitología y emergencias microbiológicas.

Existen diferencias significativas entre el tiempo de rotación clínica para los residentes con vía de acceso MIR respecto a los residentes de otras titulaciones.

Los encuestados perciben un grado de responsabilidad alto y un acuerdo medio con la calidad de la docencia. La asistencia a sesiones clínicas y la realización de rotaciones externas es frecuente.

La actividad investigadora se percibe como complicada, tanto a nivel de realización del doctorado como respecto a introducirse en líneas de investigación y la publicación de resultados científicos.

ConclusiónSe han identificado algunos puntos de mejora del itinerario formativo que es necesario reforzar. Igualmente, sería interesante buscar un mejor equilibrio entre la actividad asistencial, docente e investigadora.

The speciality of Microbiology and Parasitology is an integral part of healthcare. Despite being a central pillar for clinical decision-making in relation to infectious disease, its importance has increased significantly in the wake of recent health crises.1–4 It is a discipline essential for the proper diagnosis and treatment of patients and which increasingly relies on multidisciplinary teams, meaning new skills and knowledge are required.5

The official programme for the speciality of Microbiology and Parasitology was put together by the corresponding National Commission and published in the Spanish Official State Gazette with ORDER SCO/3256/2006 of 2 October 2006.6 It consists of four years of training and different access degrees are considered: Medicine; Pharmacy; Biology; and Chemistry and Biochemistry; with the Medicine and Pharmacy access routes being the most common. The programme has several sections, which detail the specific contents and training objectives, as well as the recommended rotations and their minimum duration.

The aim of this survey was to analyse the degree of implementation of the official programme at different Spanish National Health System hospitals. As a secondary objective, we sought to assess the satisfaction of residents with teaching, training and research at their hospitals in order to identify possible areas for improvement.

Material and methodsWe designed an anonymous online survey and distributed it through the Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica [Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology] (SEIMC) Commission of Residents and Young Specialists (CoREIMC). A period of 18 calendar days was allowed for active residents to respond.

The survey was divided into eight sections (Appendix A, Table A.1): one section on details about the respondent; six sections on the speciality following the distribution set out in the official programme (general aspects, laboratory training, clinical training, teaching, external rotations and research); and a final section on the implementation of the official programme at the hospital where the respondent was doing his or her residency.

Results for categorical variables are expressed as absolute and relative frequencies. Results for numerical variables are expressed as median (interquartile range [IQR]) and were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. The results of the scaled variables are expressed as mode.

R software (https://cran.r-project.org/) was used for statistical analysis and data visualisation.

ResultsGeneral aspectsSixty-nine responses were received: 26 (37.7%) were from fourth-year residents, 23 (33.3%) from second-year residents, 15 (21.7%) from third-year residents and 5 (7.1%) from first-year residents.

The entry routes to the specialised medical training were Pharmacy (38; 55%), Medicine (23; 33%), Biology (7; 10.1%) and Chemistry (1; 1.4%) (Fig. 1). Thirty-seven (53.6%) residents found differences in their training schedule according to the entry route to the specialised training, while 49 (42%) did not. Three (4.3%) respondents worked at hospitals that only accepted one single entry route for residency. In terms of geographical distribution, the majority of responses came from residents of the Madrid Region (30; 43.5%), followed by Catalonia and Andalusia. No responses were received from the Autonomous Regions of Asturias, Cantabria, La Rioja or Extremadura (Fig. 1).

Forty (58%) respondents thought that Clinical Microbiology and Parasitology was the most appropriate name for the speciality, followed by Clinical Microbiology (20 responses, 29%). The remaining options were in the minority: Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (2); Microbiology and Parasitology (5); Microbiology (1); and Infectious Diseases (1).

In 53 cases (76.8%) the residents surveyed considered the current four-year duration for the speciality to be adequate, compared to 16 (23.2%) who would extend it. None of the respondents suggested shortening it.

Laboratory trainingSystematic bacteriology was the area in which a majority of respondents reported feeling best prepared (60; 87.0%), followed by antimicrobials (35; 50.7%) and clinical aspects of microbiology (31; 45.0%). In contrast, mycology and parasitology were the areas in which respondents reported being least prepared (34; 49.3% for both), followed by microbiological emergencies and bioterrorism (30; 43.5%). The results are shown in Fig. 2.

Eight respondents left an optional comment (Appendix B, Table B.1).

Clinical trainingThe number of months spent on clinical training, understood as rotations in medical units, resulted in a median of three (IQR: 4). The median number of departments or units rotated through was two (IQR: 3). Six (8.7%) respondents reported not having any scheduled clinical rotations (4 non-medical residents and 2 medical residents) (Fig. 3).

Clinical rotations during residency A) number of months between medical residents and non-medical residents; B) number of different clinical rotations (for example, paediatrics, infectious diseases) broken down for the four possible entry routes. Only one response was received from a Chemistry graduate resident.

In a disaggregated analysis of the data, the majority of residents did their rotations in Infectious Diseases (87%). Other departments or units with frequent clinical rotations were Internal Medicine (29%), HIV (24.6%), Tropical Medicine (23.2%), Accident and Emergency (17.4%), Intensive Care Unit (15.9%) and Paediatrics (8%).

TeachingThe evaluation of the quality of teaching has a mode of 3 on a scale of 5. The degree of responsibility has a mode of 4 out of 5. Sixty respondents (87%) stated that the scheduled times for external rotations were respected. Twenty-six respondents (37.7%) expressed that they frequently had to cover for specialists and that their rotations were affected because of this.

Thirty-five respondents (50.7%) stated that attendance at clinical sessions was frequent compared to thirteen (18.8%) who considered it infrequent. In a similar question, this time referring to continuing education courses, 28 (40.6%) stated that they frequently attended compared to 23 (33.3%) who stated that they did not.

External rotationsSixty-seven (97.1%) of the residents responded that an external rotation was envisaged. Forty-nine (71%) had decided where to rotate with support from the department in making their choice, while 13 (18.8%) believed that their department did not provide facilities and seven (10.1%) that rotations were already decided in advance.

Forty-four (63.8%) considered that the time available was sufficient to do the desired external rotations.

ResearchTwenty-eight residents (41.2%) responded that starting a PhD during the specialised training was common but not always done, while 13 (19.1%) considered it quite established and 27 (39.7%) considered it very difficult.

Most of the respondents had the opportunity to enter into research lines within their department, but while 14 (20.3%) considered it common for residents to participate and remain in them during their training, 40 (58%) felt that it required a great deal of initiative on the part of the resident to become involved. Fifteen (21.7%) residents had no opportunity to become involved in research, either because there was none or because it was not available to residents.

In relation to that, only 17 (25%) considered it easy to publish. Twenty-five (36.8%) finished the specialised training with some publications, while 26 (38.2%) considered publishing very difficult.

Overall assessmentThe majority of respondents gave their training plan a score of 7 out of 10.

Thirty-three (47.8%) responded to the question on which aspects of the official programme for the speciality they considered the strongest, while 35 (50.7%) responded to the question on which aspects could be improved.

The responses are shown in detail in Appendix B (Tables B.2, B.3 and B.4)

DiscussionThe results of this survey provide us with an in-depth analysis of the current situation in the speciality of Microbiology and Parasitology in Spain.

Based on the four previous entrance exam sessions, we can estimate the number of residents at the time of the survey to be 3077–10 (Appendix C, Table C.1), so we have received the opinions of approximately 20% of the active residents. Although the representation of first year residents is less than 10%, we consider the distribution over the remaining years to be representative enough to draw valid conclusions. The lower number of responses among first-year residents is possibly due to the fact that at the time of the survey they had only been in residency for four months as a result of the delays in the 2019/2020 entrance exam session caused by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

A majority wanted the term “clinical” to be in the name of the speciality, as 87.0% of the answers included this terminology. With regard to the duration of the speciality, a majority (76.8%) perceived that its current duration is adequate compared to 23.2% who considered that it should be extended. The European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS) has tried to unify the disciplines to be covered by the speciality of medical microbiology in a European programme11 and, although they consider a mainly medical entry profile, they recommend a total duration of 60 months, 24 of them in the laboratory. A review carried out by the Trainee Association of ESCMID [European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases] (TAE) found that at a European level the average duration is five years, meaning Spain falls short.12 Similar results were found in a Europe-wide survey.13

Training in bacteriology, antimicrobials and clinical aspects of microbiology stand out as the areas in which respondents say they are best trained. These results are encouraging considering the relevance of bacterial infections and antibiotic resistance in the present and future of the speciality. At the other extreme, parasitology and mycology are the rotations in which respondents feel the worst trained. Currently, the recommended time in the official programme for each of these areas is two months.6 It might be interesting to explore the reasons for this and reconsider the duration, even though it is in line with the UEMS recommendations.11 The deficits that residents report in their training for microbiological emergencies take on a special importance given the circumstances of recent years. We need more training for our future specialists to enable them to deal safely with such situations, which we expect to occur with increasing frequency.14

With regard to clinical training, the results show significant differences in the time spent depending on the respondents' degree of origin (median [IQR]: medical residents 88; non-medical residents 21). The activity of Microbiology and Parasitology specialists is framed within both a laboratory and clinical context. The official programme stresses the importance of individualising each case in order to compensate for possible shortfalls according to the entry route. The UEMS recommends a minimum of 12 months training in clinical medicine.11,12 We have to remember that Spain is unusual within the European Union; it allows multiple entry routes to the specialised training in Microbiology, as well as being one of the few countries that does not recognise the speciality of Infectious Diseases (ID).12,13 This brings with it the difficulty of schools having to adapt to multiple profiles and sheds light on the diversity seen in the survey results. At the end of the specialised training, while the medical residents will be the only ones with competencies in the diagnosis and treatment of patients.15 all the specialists should have a full understanding of how things work in the medical units. This clashes with some respondents who state that they are not allowed to rotate in clinical units because they are not doctors, and it is cause for thought.

Teaching is one of the aspects of the survey to have sparked the most comments. The majority of respondents gave a 3 out of 5 to the teaching at their schools, considering the level of responsibility they have to assume to be high. Almost 40% felt that their rotations were affected by having to cover frequently for specialists, although the length of their external rotations was maintained. Placements at other institutions as well as attendance at sessions and courses are encouraged by all institutions and societies as a way of completing training.12,15 The results are encouraging in this respect, but there are still 20% and 30% of respondents respectively who find it difficult to attend sessions or courses. It is essential to maintain a balance between training and the responsibility that the resident needs to be acquiring in the routine work of the laboratory. To be fully aware of all this, the figure of the tutor is fundamental. Tutors should have a manageable number of trainees under their charge and time to interview them, receive feedback and evaluate their rotations with the different methodologies available to them.16

In terms of research activity, 58% of the respondents stated that, despite the existence of research lines, it requires a great deal of initiative on the part of the resident to be able to participate. Similarly, 38% consider that it is very difficult to publish in scientific journals and only in 20% of the cases is doing a doctorate a common and established activity. This contrasts with the research objectives defined in the official programme,15 which encourage residents' participation in research teams and enrolment in doctoral programmes, as well as stressing the importance of a specific research methodology programme. The UEMS even proposes a final project leading to a publication11 and more advanced specialisations related to clinical microbiology, such as the European Public Health Microbiology Training Programme (EUPHEM), require field research.17

The main limitation is the unequal representation of Spain's different autonomous regions. The over-representation of residents from the Madrid Region particularly stands out (30 responses, 43.5%). In general, tertiary hospitals in cities such as Madrid, Barcelona or Valencia are larger, cover all areas and require fewer external rotations to complete the training. The results of the survey may lose external validity, but it also raises the question of whether extrapolation of the shortcomings identified by these residents to smaller hospitals with more limited resources could show the situation there to be even worse. We have not been able to study relationships between the type of hospital and possible training problems due to potential errors in the responses (we found a very high percentage of primary hospitals, which usually lack a specialised training course in microbiology and parasitology, leading us to suspect a possible confusion between the terms primary and tertiary hospital).

In general, residents rate the implementation of their training plan with a 7 out of 10. Responses regarding the strongest aspects of their training plan were very heterogeneous. In contrast, in the responses regarding which aspects they would improve, although also showing variability and some contradictory answers, more emphasis was placed on teaching, research and clinical training. Rotations, both internal and external, are also a much discussed issue, with reference to their duration and the possibility of introducing more flexibility.

From the results of this survey, we have been able to identify training areas in which teaching needs to be improved, mycology and parasitology in particular. Additionally, emphasis should be placed on the clinical training of non-medical residents and on the development of research activity, always within the capabilities of the centre. Greater teaching involvement from all specialists, encouraged by training and time for them to devote to residents, is essential for effective learning.

We need to make efforts to move towards better coordination of care, teaching and research activities, all of which are essential for the effective training of new specialists in Clinical Microbiology and Parasitology. Future editions of this survey could provide more information on how the training in our speciality is progressing.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.

Authors/contributorsBoth authors have contributed equally to the conduct of this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

To the SEIMC Board of Directors for their support in the creation and maintenance of this committee, to Javier Ávila for his availability and dedication and, especially, to the other members of CoREIMC and to all the residents who answered the survey and made this analysis possible.