The VINCat Program: a 19-year model of success in infection prevention and control of healthcare-associated infections in Catalonia, Spain

More infoThis study presents comprehensive data on antimicrobial susceptibility across healthcare settings and age groups in Catalonia, Spain.

MethodsSusceptibility data were collected from 37 microbiology laboratories between 2020 and 2022 for community-acquired infections (CAIs), and 2021 and 2022 for hospital and long-term care facilities (LTCFs). Susceptibility was calculated based on the proportion of susceptible strains among the total strains.

ResultsPediatrics: Community-acquired infections (CAIs): in urinary tract infections (UTIs), extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production (ESBL-P) Escherichia coli was 3.8%. Streptococcus pneumoniae was highly susceptible to penicillins (97.5%). Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was 6.8%. Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs): ESBL-P in E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae were 6.7% and 9.4%. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacter cloacae complex was less than 1%. Extremely drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa was 1.6%.

AdultsCAIs: In UTIs, E. coli showed high susceptibility to fosfomycin (>95%) and 9% of ESBL-P. In respiratory tract infections, Streptococcus pyogenes exhibited reduced susceptibility to macrolides (67%) and clindamycin (75.1%), while Haemophilus influenzae and S. pneumoniae remained susceptible to penicillins (78% and 96%). HAIs: E. coli showed 12.8% of ESBL-P and K. pneumoniae 20%. Carbapenem resistance was mainly identified in E. cloacae (2.8%) and K. pneumoniae (2.2%). P. aeruginosa showed high susceptibility to meropenem (87%). Methicillin-resistance was detected in 22% of S. aureus.

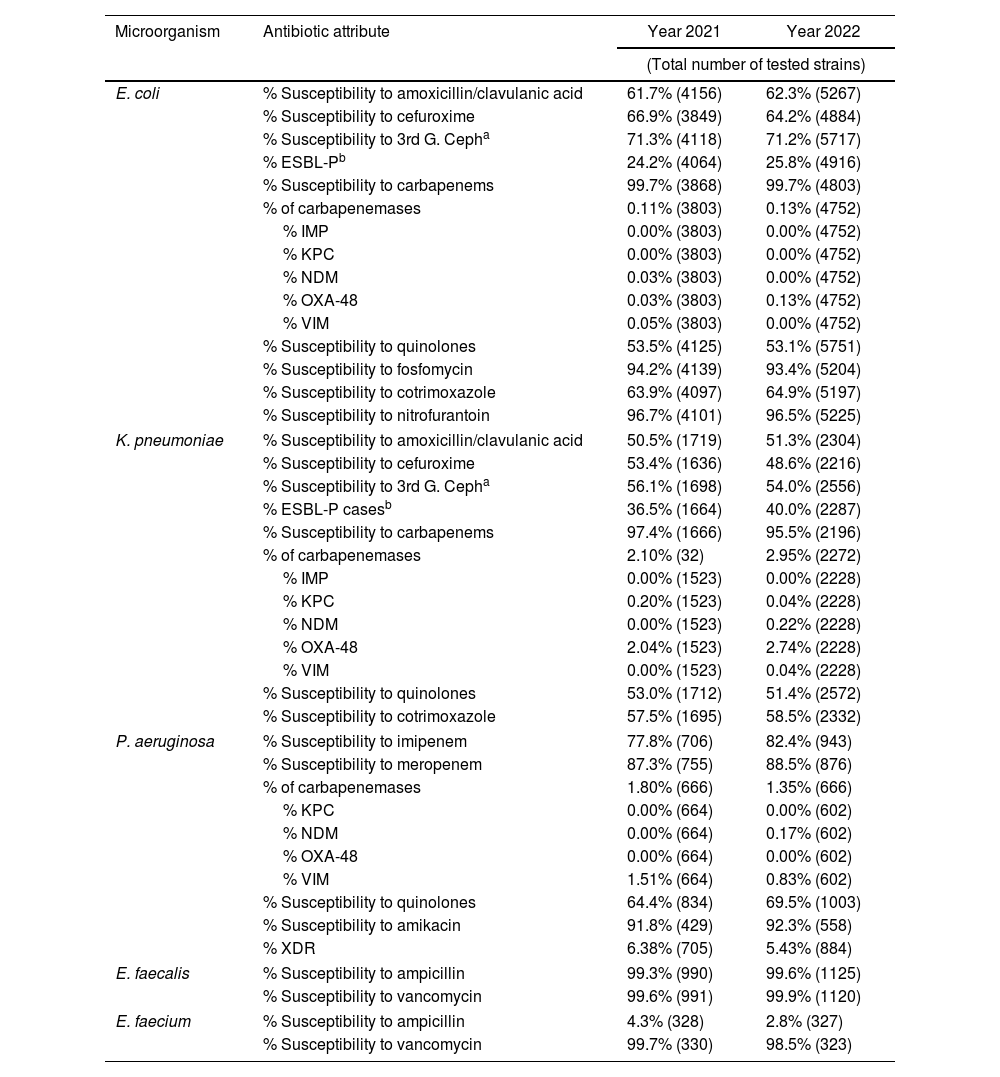

Long-term care facilities (LTCFs): E. coli causing UTI was highly susceptible to carbapenems (99%), nitrofurantoin (96%), and fosfomycin (93%) with 25.8% of ESBL-P. K. pneumoniae showed 40% ESBL-P and 2.9% of carbapenem resistance. P. aeruginosa exhibited decreased susceptibility to quinolones (69.5%) and highly susceptibility to meropenem (88.5%).

ConclusionThe data underscore the necessity of stratified susceptibility reports by setting, type of infection, and age.

Objetivo Presentar los datos de sensibilidad antimicrobiana en los distintos entornos sanitarios y grupos de edad en Cataluña, España.

MétodosSe recopilaron datos de sensibilidad de 37 laboratorios de microbiología entre 2020 y 2022 para infecciones adquiridas en la comunidad, y entre 2021 y 2022 para hospitales y centros sociosanitarios. Sensibilidad: proporción de cepas sensibles del total de cepas estudiadas.

ResultadosAdultos: adquisición comunitaria (AC). Infecciones urinarias (ITU): Escherichia coli, elevada sensibilidad a la fosfomicina (95,8%) y 9% de betalactamasas de espectro extendido (BLEE). Infecciones respiratorias:Streptococcus pyogenes, sensibilidad reducida a macrólidos (67%) y clindamicina (75,1%). Haemophilus influenzae y Streptococcus pneumoniae, sensibilidad mantenida a penicilinas (78 y 96%, respectivamente). Adquisición hospitalaria (AH): E. coli, 12,8% BLEE. Klebsiella pneumoniae, 20% BLEE. Resistencia a carbapenémicos en Enterobacter cloacae (2,8%) y K. pneumoniae (2,2%). Pseudomonas aeruginosa, elevada sensibilidad a meropenem (87%). Staphylococcus aureus resistente a meticilina en un 22%. Pediatría. AC: BLEE en 3,8% E. coli causantes de ITU. S. pneumoniae, elevada sensibilidad a penicilinas (97,5%). La resistencia a meticilina en S. aureus comunitario 6,8%. AH: BLEE en E. coli (6,7%) y K. pneumoniae (9,4%). En E. cloacae, la resistencia a carbapenémicos fue menor del 1%. El porcentaje de aislados de P. aeruginosa extremadamente resistente fue del 1,6%. Centros sociosanitarios. ITU: en E. coli, elevada sensibilidad a carbapenémicos (99%), nitrofurantoína (96%) y fosfomicina (93%); se detectó BLEE en el 25,8%. En K. pneumoniae, se identificó BLEE en el 40% y en un 2,9% de resistencia a carbapenémicos. P. aeruginosa exhibió disminución de la sensibilidad a quinolonas (69,5%) y elevada sensibilidad a meropenem (88,5%).

ConclusiónLos datos resaltan la necesidad de disponer de informes de sensibilidad estratificados según el entorno, el tipo de infección y la edad.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a critical global public health threat.1 Obtaining comprehensive epidemiological data on the antibiotic susceptibility of major pathogens causing infections, reflecting local, regional, national, and international trends, is essential.2 These data are crucial for developing and updating guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis and empirical treatments. Regional data enhance sample size, bolster the robustness of the information provided, and facilitate the detection of resistance trends. Furthermore, they allow for potential correlations with antimicrobial use and identification of high-risk clones.

In Catalonia, Spain, with a population of over 8million in 2024, the Catalan Public Health Agency (ASPCAT) collects antibiotic susceptibility data through the Catalan Microbiological Notification System (SNMC). Additionally, the VINCat Program, which is responsible for infection prevention and control of healthcare-associated infections in Catalonia, has been surveying hospital antibiotic consumption since 2007.3,4 In 2012, VINCat launched the Antimicrobial Stewardship Program (ASP) in hospitals, later expanding it to include long-term care facilities (LTCFs) and primary care settings.

Since 2019, leading microbiologists from VINCat have standardized criteria and procedures to develop comprehensive antibiotic resistance maps across different levels of care throughout the region. In 2020, the VINCat Program introduced antibiotic susceptibility indicators specifically for primary care, which were subsequently expanded to acute care hospitals and LTCFs. These indicators, which target key microorganisms (ESKAPE), are stratified by adult and pediatric populations.5,6 However, despite AMR surveillance programs providing national and international data, information on pediatric populations remains scarce.7,8 This gap is particularly concerning given that infectious diseases are a leading cause of pediatric medical consultations, with antimicrobials being the most prescribed agents.9 Relying on adult resistance, data to guide pediatric treatments can lead to increased use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, further driving resistance and the incidence of Clostridioides difficile infections.10 The growing resistance, coupled with the limited treatment options for multidrug-resistant (MDR) pediatric infections, underscores the urgent need for pediatric-specific antibiotic susceptibility data.11

LTCFs are playing an increasingly crucial role in Catalonia's healthcare system, which is driven by an aging population and the growing demand for continuous care following acute care stays. These centers are characterized by a high prevalence of residents with functional dependence, cognitive impairment, and multiple comorbidities. It is estimated that up to 70% of residents in these facilities will receive antibiotic treatment annually, primarily for urinary and respiratory infections.12 However, a significant proportion of these treatments are deemed inappropriate, highlighting the critical need for multidisciplinary ASP teams to optimize antimicrobials.13

The aim of our study is to present susceptibility data on key microorganisms responsible for infections in both children and adults across the entire healthcare system, including acute care hospitals, LTCFs, and primary care centers involved in the VINCat program.

MethodsThirty-seven microbiology laboratories collected antibiotic susceptibility data between 2020 and 2022 from the community setting and between 2021 and 2022 from the hospital and LTCFs settings in Catalonia. The data were stratified by pediatric and adult populations. Pediatric data were obtained from 34 hospitals in 2021 and 44 in 2022. For the adult population, 56 hospitals contributed data in 2021 and 58 in 2022. Information from LTCFs was gathered from 68 facilities in 2021 and 78 in 2022. Antibiotic susceptibility data were also obtained from 370 primary care centers distributed throughout the Catalan Integrated Public Healthcare System between 2020 and 2022 (Supplementary Table 1).

The susceptibility rate was calculated by dividing the number of susceptible and “susceptible, increased exposure” strains by the total number of strains tested, following the guidelines set by the Spanish Antibiogram Committee (COESANT), the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC), and the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST).14,15 The EUCAST breakpoints relevant to the current year were applied in all analyses.15

Study population: For the purposes of this study, isolates collected from five different healthcare settings were analyzed:

- 1.

Pediatrics, community: Data were collected from isolates of patients under 15 years of age treated in primary care centers for UTIs, respiratory tract infections, enteritis, or skin infections.

- 2.

Pediatrics, hospital: Isolates were collected from patients under 18 years of age hospitalized in any area of acute care hospitals.

- 3.

Adults, community: Data were collected from isolates of patients aged 15 years and older who were treated in primary care centers for urinary tract infections (UTIs), respiratory tract infections, or sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

- 4.

Adults, hospital: Isolates were gathered from patients aged 18 years and older hospitalized in any area of acute care hospitals.

- 5.

LTCFs: Isolates were selected from residents who developed UTIs while residing in LTCFs.

Inclusion criteria for isolates: Antibiotic susceptibility results were included if they were obtained from interpreted antibiograms of strains isolated from diagnostic-purpose culture samples. Strains from surveillance samples, active carrier searches, or environmental studies were excluded. Only the first isolate from each patient per year was considered, in line with COESANT recommendations.14 Extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Pseudomonas aeruginosa was defined according to the criteria of Magiorakos et al.16 For each isolate, the following data were recorded: sample source, reporting laboratory, patient age, sex, date of sample collection, sample type, genus and species, antibiotic susceptibility, and proposed resistance mechanisms.

Data analysis: Susceptibility percentages for hospitalized patients were grouped by microorganisms, focusing on those of most significant clinical relevance due to the frequency of infections they cause and their role in the dissemination of resistance. Susceptibility percentages from community and LTCF settings were classified according to clinical syndromes to guide the empirical treatment of the most common infections.

Comparisons of susceptibility percentages between adult and pediatric populations in community and hospital settings were made using appropriate Chi-square tests or Fisher's exact tests. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated to assess the strength of associations. A significance level of 0.05 was applied for all two-tailed statistical tests. Statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.2.2, developed by The R Foundation in Vienna, Austria.

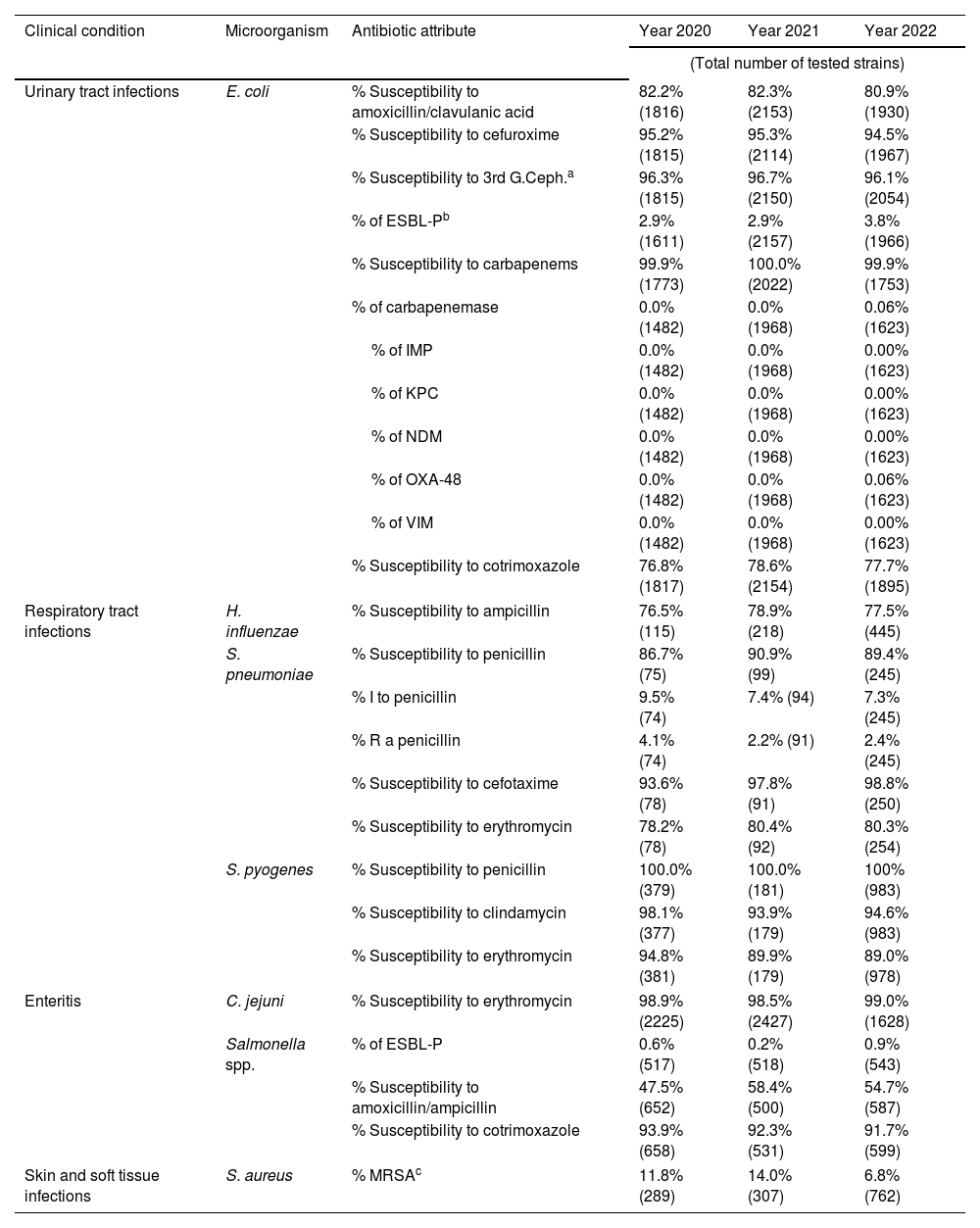

ResultsAntimicrobial susceptibility in pediatric community-acquired infectionsTable 1 presents data on antibiotic susceptibility in pediatric community-acquired infections. The susceptibility of Escherichia coli, the primary cause of community-acquired UTIs in children, remained stable throughout the study period. However, a slight increase in ESBL-producing isolates was noted, rising to 3.8% in 2022. This increase led to a minor decrease in E. coli susceptibility to amoxicillin–clavulanic acid and cefuroxime. Notably, in 2022, the first carbapenemase-producing E. coli isolate from the community was detected. In community-acquired enteritis, Campylobacter jejuni maintained high susceptibility to erythromycin throughout the study. The prevalence of ESBL-producing Salmonella spp. was low (0.9%) in 2022, while susceptibility to cotrimoxazole remained high. Additionally, there was a decrease in community-acquired MRSA in children, dropping to 6.8% in 2022. Similarly, the proportion of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae causing respiratory infections in the community declined to 2.5% in 2022.

Antimicrobial susceptibility in community-acquired infections. Pediatrics.

| Clinical condition | Microorganism | Antibiotic attribute | Year 2020 | Year 2021 | Year 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Total number of tested strains) | |||||

| Urinary tract infections | E. coli | % Susceptibility to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 82.2% (1816) | 82.3% (2153) | 80.9% (1930) |

| % Susceptibility to cefuroxime | 95.2% (1815) | 95.3% (2114) | 94.5% (1967) | ||

| % Susceptibility to 3rd G.Ceph.a | 96.3% (1815) | 96.7% (2150) | 96.1% (2054) | ||

| % of ESBL-Pb | 2.9% (1611) | 2.9% (2157) | 3.8% (1966) | ||

| % Susceptibility to carbapenems | 99.9% (1773) | 100.0% (2022) | 99.9% (1753) | ||

| % of carbapenemase | 0.0% (1482) | 0.0% (1968) | 0.06% (1623) | ||

| % of IMP | 0.0% (1482) | 0.0% (1968) | 0.00% (1623) | ||

| % of KPC | 0.0% (1482) | 0.0% (1968) | 0.00% (1623) | ||

| % of NDM | 0.0% (1482) | 0.0% (1968) | 0.00% (1623) | ||

| % of OXA-48 | 0.0% (1482) | 0.0% (1968) | 0.06% (1623) | ||

| % of VIM | 0.0% (1482) | 0.0% (1968) | 0.00% (1623) | ||

| % Susceptibility to cotrimoxazole | 76.8% (1817) | 78.6% (2154) | 77.7% (1895) | ||

| Respiratory tract infections | H. influenzae | % Susceptibility to ampicillin | 76.5% (115) | 78.9% (218) | 77.5% (445) |

| S. pneumoniae | % Susceptibility to penicillin | 86.7% (75) | 90.9% (99) | 89.4% (245) | |

| % I to penicillin | 9.5% (74) | 7.4% (94) | 7.3% (245) | ||

| % R a penicillin | 4.1% (74) | 2.2% (91) | 2.4% (245) | ||

| % Susceptibility to cefotaxime | 93.6% (78) | 97.8% (91) | 98.8% (250) | ||

| % Susceptibility to erythromycin | 78.2% (78) | 80.4% (92) | 80.3% (254) | ||

| S. pyogenes | % Susceptibility to penicillin | 100.0% (379) | 100.0% (181) | 100% (983) | |

| % Susceptibility to clindamycin | 98.1% (377) | 93.9% (179) | 94.6% (983) | ||

| % Susceptibility to erythromycin | 94.8% (381) | 89.9% (179) | 89.0% (978) | ||

| Enteritis | C. jejuni | % Susceptibility to erythromycin | 98.9% (2225) | 98.5% (2427) | 99.0% (1628) |

| Salmonella spp. | % of ESBL-P | 0.6% (517) | 0.2% (518) | 0.9% (543) | |

| % Susceptibility to amoxicillin/ampicillin | 47.5% (652) | 58.4% (500) | 54.7% (587) | ||

| % Susceptibility to cotrimoxazole | 93.9% (658) | 92.3% (531) | 91.7% (599) | ||

| Skin and soft tissue infections | S. aureus | % MRSAc | 11.8% (289) | 14.0% (307) | 6.8% (762) |

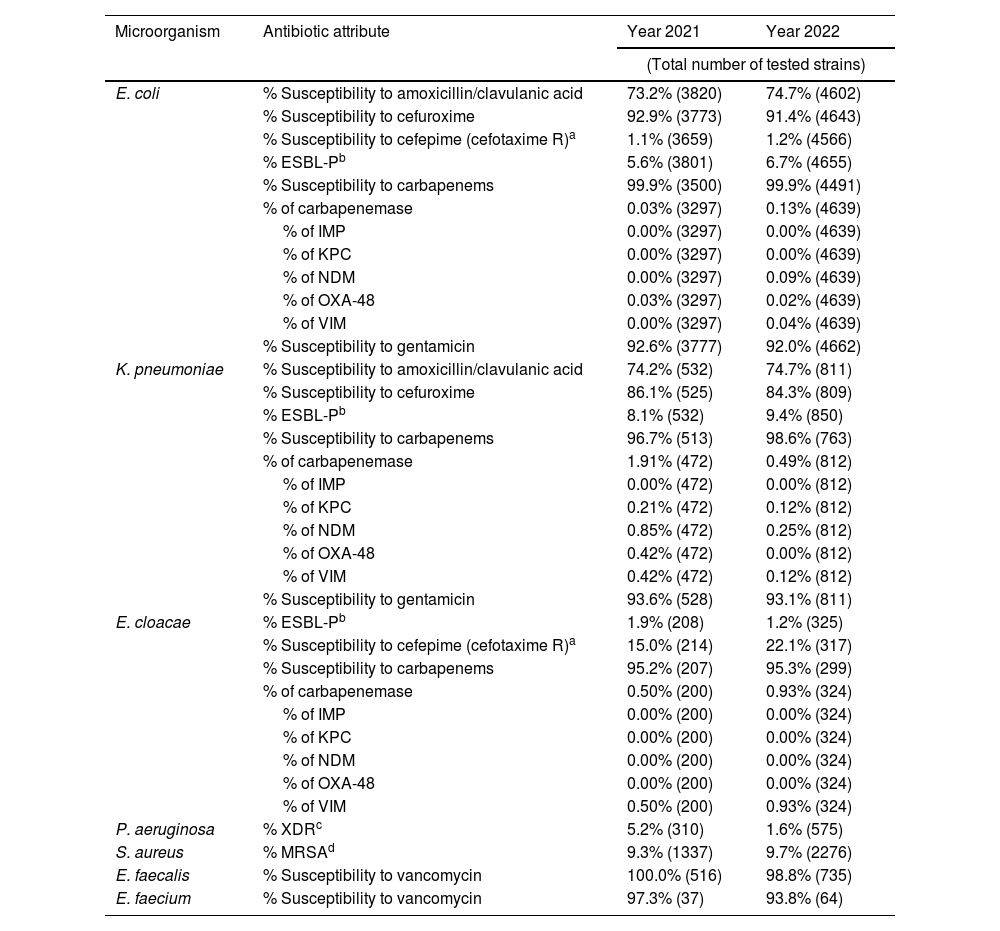

Table 2 outlines the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns in the pediatric hospital setting. The prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli isolates increased slightly to 6.7% in 2022, while susceptibility to cephalosporins and aminoglycosides remained high. Similarly, the prevalence of ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae rose to 9.4% in 2022, although the proportion of carbapenemase-producing strains decreased during the same period. The prevalence of AmpC hyperproducing Enterobacter cloacae complex also increased, reaching 22.6% in 2022, while the proportion of carbapenemase-producing E. cloacae complex strains remained low. Notably, the incidence of XDR P. aeruginosa isolates decreased to 1.6% in 2022.

Antibiotic susceptibility in hospital-acquired infections. Pediatrics.

| Microorganism | Antibiotic attribute | Year 2021 | Year 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Total number of tested strains) | |||

| E. coli | % Susceptibility to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 73.2% (3820) | 74.7% (4602) |

| % Susceptibility to cefuroxime | 92.9% (3773) | 91.4% (4643) | |

| % Susceptibility to cefepime (cefotaxime R)a | 1.1% (3659) | 1.2% (4566) | |

| % ESBL-Pb | 5.6% (3801) | 6.7% (4655) | |

| % Susceptibility to carbapenems | 99.9% (3500) | 99.9% (4491) | |

| % of carbapenemase | 0.03% (3297) | 0.13% (4639) | |

| % of IMP | 0.00% (3297) | 0.00% (4639) | |

| % of KPC | 0.00% (3297) | 0.00% (4639) | |

| % of NDM | 0.00% (3297) | 0.09% (4639) | |

| % of OXA-48 | 0.03% (3297) | 0.02% (4639) | |

| % of VIM | 0.00% (3297) | 0.04% (4639) | |

| % Susceptibility to gentamicin | 92.6% (3777) | 92.0% (4662) | |

| K. pneumoniae | % Susceptibility to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 74.2% (532) | 74.7% (811) |

| % Susceptibility to cefuroxime | 86.1% (525) | 84.3% (809) | |

| % ESBL-Pb | 8.1% (532) | 9.4% (850) | |

| % Susceptibility to carbapenems | 96.7% (513) | 98.6% (763) | |

| % of carbapenemase | 1.91% (472) | 0.49% (812) | |

| % of IMP | 0.00% (472) | 0.00% (812) | |

| % of KPC | 0.21% (472) | 0.12% (812) | |

| % of NDM | 0.85% (472) | 0.25% (812) | |

| % of OXA-48 | 0.42% (472) | 0.00% (812) | |

| % of VIM | 0.42% (472) | 0.12% (812) | |

| % Susceptibility to gentamicin | 93.6% (528) | 93.1% (811) | |

| E. cloacae | % ESBL-Pb | 1.9% (208) | 1.2% (325) |

| % Susceptibility to cefepime (cefotaxime R)a | 15.0% (214) | 22.1% (317) | |

| % Susceptibility to carbapenems | 95.2% (207) | 95.3% (299) | |

| % of carbapenemase | 0.50% (200) | 0.93% (324) | |

| % of IMP | 0.00% (200) | 0.00% (324) | |

| % of KPC | 0.00% (200) | 0.00% (324) | |

| % of NDM | 0.00% (200) | 0.00% (324) | |

| % of OXA-48 | 0.00% (200) | 0.00% (324) | |

| % of VIM | 0.50% (200) | 0.93% (324) | |

| P. aeruginosa | % XDRc | 5.2% (310) | 1.6% (575) |

| S. aureus | % MRSAd | 9.3% (1337) | 9.7% (2276) |

| E. faecalis | % Susceptibility to vancomycin | 100.0% (516) | 98.8% (735) |

| E. faecium | % Susceptibility to vancomycin | 97.3% (37) | 93.8% (64) |

Across both hospital and community settings, the antibiotic susceptibility of pediatric isolates was generally higher compared to those of adults. These differences were statistically significant for all antibiotics and resistance mechanisms studied, except for E. coli susceptibility to carbapenems and cotrimoxazole in the community, as well as the rates of carbapenemase-producing E. coli strains in both community and hospital settings (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

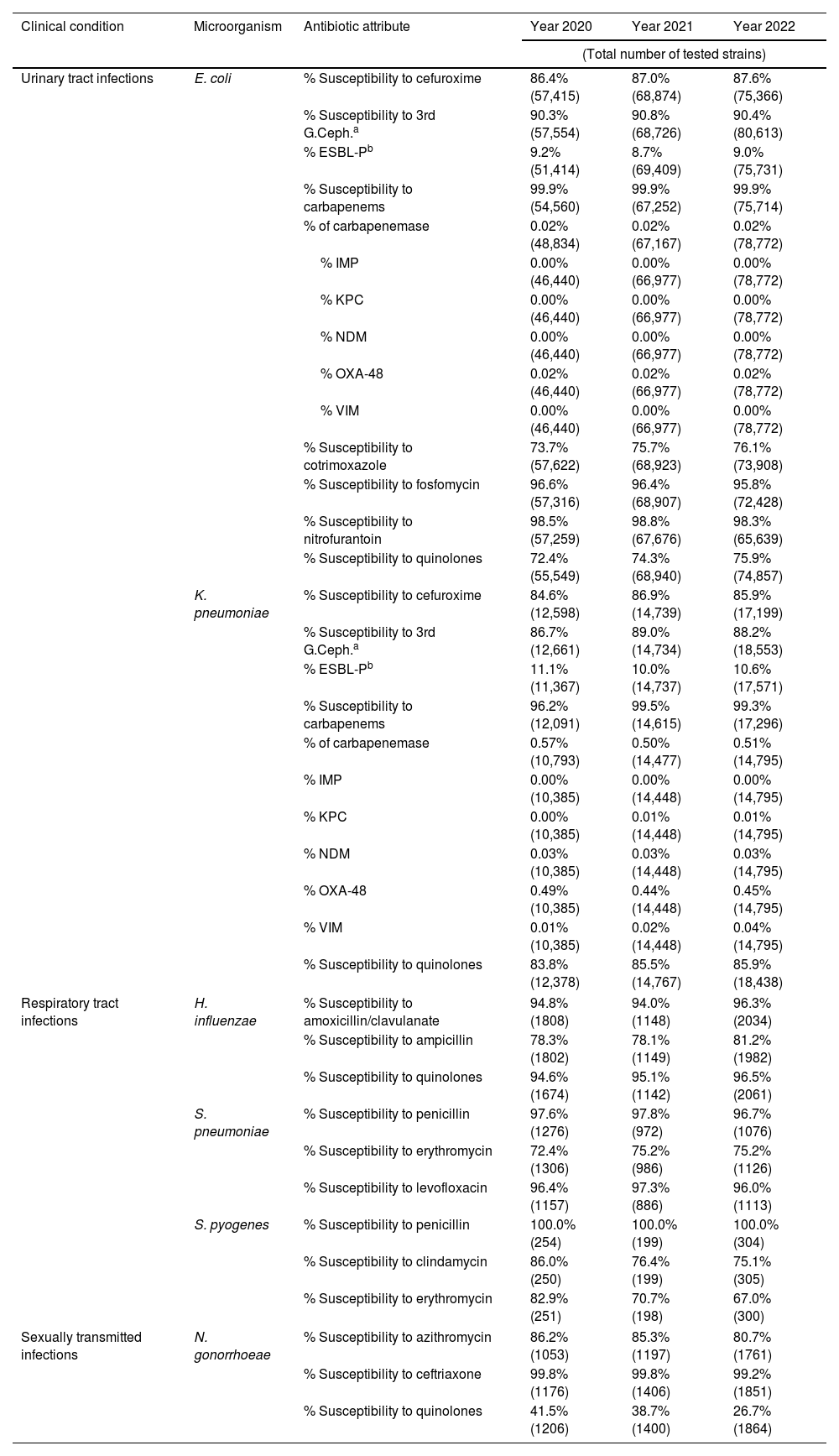

Antimicrobial susceptibility in adult community-acquired infectionsTable 3 outlines the antibiotic susceptibility data for community-acquired infections in adults. For UTIs, E. coli maintained a high susceptibility to fosfomycin throughout the three-year study period. The prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing E. coli remained stable at over 9%, while carbapenemase-producing strains accounted for only 0.02% of isolates. K. pneumoniae, the second most common cause of community-acquired UTIs, showed a slight decrease in the proportion of ESBL-producing strains in 2022, compared to 2020 (10.6% vs. 11.1%). Carbapenemase-producing strains were detected in 0.5% of the isolates, with OXA-48 being the most frequently identified type. For respiratory tract infections, a significant decline in the susceptibility of Streptococcus pyogenes to both macrolides and clindamycin was observed. In contrast, S. pneumoniae consistently maintained high susceptibility to penicillin throughout the study, as did Haemophilus influenzae to ampicillin and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid. Regarding STIs, Neisseria gonorrhoeae showed a notable decrease in susceptibility to quinolones and macrolides. However, susceptibility to third-generation cephalosporins remained consistently high.

Antimicrobial susceptibility in community-acquired infections. Adults.

| Clinical condition | Microorganism | Antibiotic attribute | Year 2020 | Year 2021 | Year 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Total number of tested strains) | |||||

| Urinary tract infections | E. coli | % Susceptibility to cefuroxime | 86.4% (57,415) | 87.0% (68,874) | 87.6% (75,366) |

| % Susceptibility to 3rd G.Ceph.a | 90.3% (57,554) | 90.8% (68,726) | 90.4% (80,613) | ||

| % ESBL-Pb | 9.2% (51,414) | 8.7% (69,409) | 9.0% (75,731) | ||

| % Susceptibility to carbapenems | 99.9% (54,560) | 99.9% (67,252) | 99.9% (75,714) | ||

| % of carbapenemase | 0.02% (48,834) | 0.02% (67,167) | 0.02% (78,772) | ||

| % IMP | 0.00% (46,440) | 0.00% (66,977) | 0.00% (78,772) | ||

| % KPC | 0.00% (46,440) | 0.00% (66,977) | 0.00% (78,772) | ||

| % NDM | 0.00% (46,440) | 0.00% (66,977) | 0.00% (78,772) | ||

| % OXA-48 | 0.02% (46,440) | 0.02% (66,977) | 0.02% (78,772) | ||

| % VIM | 0.00% (46,440) | 0.00% (66,977) | 0.00% (78,772) | ||

| % Susceptibility to cotrimoxazole | 73.7% (57,622) | 75.7% (68,923) | 76.1% (73,908) | ||

| % Susceptibility to fosfomycin | 96.6% (57,316) | 96.4% (68,907) | 95.8% (72,428) | ||

| % Susceptibility to nitrofurantoin | 98.5% (57,259) | 98.8% (67,676) | 98.3% (65,639) | ||

| % Susceptibility to quinolones | 72.4% (55,549) | 74.3% (68,940) | 75.9% (74,857) | ||

| K. pneumoniae | % Susceptibility to cefuroxime | 84.6% (12,598) | 86.9% (14,739) | 85.9% (17,199) | |

| % Susceptibility to 3rd G.Ceph.a | 86.7% (12,661) | 89.0% (14,734) | 88.2% (18,553) | ||

| % ESBL-Pb | 11.1% (11,367) | 10.0% (14,737) | 10.6% (17,571) | ||

| % Susceptibility to carbapenems | 96.2% (12,091) | 99.5% (14,615) | 99.3% (17,296) | ||

| % of carbapenemase | 0.57% (10,793) | 0.50% (14,477) | 0.51% (14,795) | ||

| % IMP | 0.00% (10,385) | 0.00% (14,448) | 0.00% (14,795) | ||

| % KPC | 0.00% (10,385) | 0.01% (14,448) | 0.01% (14,795) | ||

| % NDM | 0.03% (10,385) | 0.03% (14,448) | 0.03% (14,795) | ||

| % OXA-48 | 0.49% (10,385) | 0.44% (14,448) | 0.45% (14,795) | ||

| % VIM | 0.01% (10,385) | 0.02% (14,448) | 0.04% (14,795) | ||

| % Susceptibility to quinolones | 83.8% (12,378) | 85.5% (14,767) | 85.9% (18,438) | ||

| Respiratory tract infections | H. influenzae | % Susceptibility to amoxicillin/clavulanate | 94.8% (1808) | 94.0% (1148) | 96.3% (2034) |

| % Susceptibility to ampicillin | 78.3% (1802) | 78.1% (1149) | 81.2% (1982) | ||

| % Susceptibility to quinolones | 94.6% (1674) | 95.1% (1142) | 96.5% (2061) | ||

| S. pneumoniae | % Susceptibility to penicillin | 97.6% (1276) | 97.8% (972) | 96.7% (1076) | |

| % Susceptibility to erythromycin | 72.4% (1306) | 75.2% (986) | 75.2% (1126) | ||

| % Susceptibility to levofloxacin | 96.4% (1157) | 97.3% (886) | 96.0% (1113) | ||

| S. pyogenes | % Susceptibility to penicillin | 100.0% (254) | 100.0% (199) | 100.0% (304) | |

| % Susceptibility to clindamycin | 86.0% (250) | 76.4% (199) | 75.1% (305) | ||

| % Susceptibility to erythromycin | 82.9% (251) | 70.7% (198) | 67.0% (300) | ||

| Sexually transmitted infections | N. gonorrhoeae | % Susceptibility to azithromycin | 86.2% (1053) | 85.3% (1197) | 80.7% (1761) |

| % Susceptibility to ceftriaxone | 99.8% (1176) | 99.8% (1406) | 99.2% (1851) | ||

| % Susceptibility to quinolones | 41.5% (1206) | 38.7% (1400) | 26.7% (1864) | ||

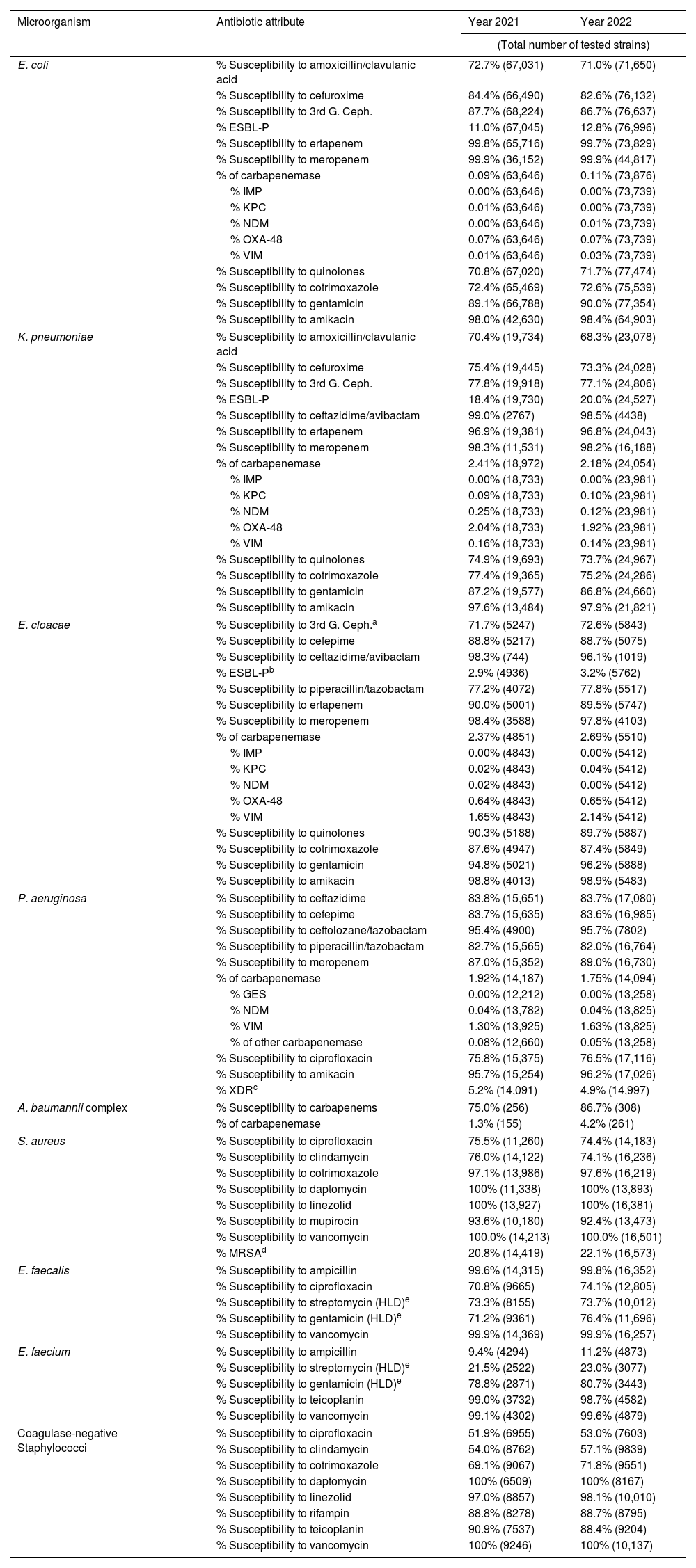

Table 4 provides antibiotic susceptibility data for hospital-acquired infections during the study period. There was a slight increase in ESBL-producing strains of E. coli and K. pneumoniae (12.8% and 20.0%, respectively), while the rates remained low in E. cloacae complex. Carbapenemase production was predominantly detected in E. cloacae complex (2.8%, mainly VIM-type) and K. pneumoniae (2.2%, primarily OXA-48 type). The susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to meropenem remained high. Over 5% of the strains were classified as XDR, with less than 2% identified as carbapenemase producers, predominantly VIM-type. Among Gram-positive bacteria, the methicillin resistance in S. aureus (MRSA) was above 22%, with high susceptibility to daptomycin and linezolid. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci were nearly undetected, with prevalence remaining below 1%.

Antimicrobial susceptibility in hospital-acquired infections. Adults.

| Microorganism | Antibiotic attribute | Year 2021 | Year 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Total number of tested strains) | |||

| E. coli | % Susceptibility to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 72.7% (67,031) | 71.0% (71,650) |

| % Susceptibility to cefuroxime | 84.4% (66,490) | 82.6% (76,132) | |

| % Susceptibility to 3rd G. Ceph. | 87.7% (68,224) | 86.7% (76,637) | |

| % ESBL-P | 11.0% (67,045) | 12.8% (76,996) | |

| % Susceptibility to ertapenem | 99.8% (65,716) | 99.7% (73,829) | |

| % Susceptibility to meropenem | 99.9% (36,152) | 99.9% (44,817) | |

| % of carbapenemase | 0.09% (63,646) | 0.11% (73,876) | |

| % IMP | 0.00% (63,646) | 0.00% (73,739) | |

| % KPC | 0.01% (63,646) | 0.00% (73,739) | |

| % NDM | 0.00% (63,646) | 0.01% (73,739) | |

| % OXA-48 | 0.07% (63,646) | 0.07% (73,739) | |

| % VIM | 0.01% (63,646) | 0.03% (73,739) | |

| % Susceptibility to quinolones | 70.8% (67,020) | 71.7% (77,474) | |

| % Susceptibility to cotrimoxazole | 72.4% (65,469) | 72.6% (75,539) | |

| % Susceptibility to gentamicin | 89.1% (66,788) | 90.0% (77,354) | |

| % Susceptibility to amikacin | 98.0% (42,630) | 98.4% (64,903) | |

| K. pneumoniae | % Susceptibility to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 70.4% (19,734) | 68.3% (23,078) |

| % Susceptibility to cefuroxime | 75.4% (19,445) | 73.3% (24,028) | |

| % Susceptibility to 3rd G. Ceph. | 77.8% (19,918) | 77.1% (24,806) | |

| % ESBL-P | 18.4% (19,730) | 20.0% (24,527) | |

| % Susceptibility to ceftazidime/avibactam | 99.0% (2767) | 98.5% (4438) | |

| % Susceptibility to ertapenem | 96.9% (19,381) | 96.8% (24,043) | |

| % Susceptibility to meropenem | 98.3% (11,531) | 98.2% (16,188) | |

| % of carbapenemase | 2.41% (18,972) | 2.18% (24,054) | |

| % IMP | 0.00% (18,733) | 0.00% (23,981) | |

| % KPC | 0.09% (18,733) | 0.10% (23,981) | |

| % NDM | 0.25% (18,733) | 0.12% (23,981) | |

| % OXA-48 | 2.04% (18,733) | 1.92% (23,981) | |

| % VIM | 0.16% (18,733) | 0.14% (23,981) | |

| % Susceptibility to quinolones | 74.9% (19,693) | 73.7% (24,967) | |

| % Susceptibility to cotrimoxazole | 77.4% (19,365) | 75.2% (24,286) | |

| % Susceptibility to gentamicin | 87.2% (19,577) | 86.8% (24,660) | |

| % Susceptibility to amikacin | 97.6% (13,484) | 97.9% (21,821) | |

| E. cloacae | % Susceptibility to 3rd G. Ceph.a | 71.7% (5247) | 72.6% (5843) |

| % Susceptibility to cefepime | 88.8% (5217) | 88.7% (5075) | |

| % Susceptibility to ceftazidime/avibactam | 98.3% (744) | 96.1% (1019) | |

| % ESBL-Pb | 2.9% (4936) | 3.2% (5762) | |

| % Susceptibility to piperacillin/tazobactam | 77.2% (4072) | 77.8% (5517) | |

| % Susceptibility to ertapenem | 90.0% (5001) | 89.5% (5747) | |

| % Susceptibility to meropenem | 98.4% (3588) | 97.8% (4103) | |

| % of carbapenemase | 2.37% (4851) | 2.69% (5510) | |

| % IMP | 0.00% (4843) | 0.00% (5412) | |

| % KPC | 0.02% (4843) | 0.04% (5412) | |

| % NDM | 0.02% (4843) | 0.00% (5412) | |

| % OXA-48 | 0.64% (4843) | 0.65% (5412) | |

| % VIM | 1.65% (4843) | 2.14% (5412) | |

| % Susceptibility to quinolones | 90.3% (5188) | 89.7% (5887) | |

| % Susceptibility to cotrimoxazole | 87.6% (4947) | 87.4% (5849) | |

| % Susceptibility to gentamicin | 94.8% (5021) | 96.2% (5888) | |

| % Susceptibility to amikacin | 98.8% (4013) | 98.9% (5483) | |

| P. aeruginosa | % Susceptibility to ceftazidime | 83.8% (15,651) | 83.7% (17,080) |

| % Susceptibility to cefepime | 83.7% (15,635) | 83.6% (16,985) | |

| % Susceptibility to ceftolozane/tazobactam | 95.4% (4900) | 95.7% (7802) | |

| % Susceptibility to piperacillin/tazobactam | 82.7% (15,565) | 82.0% (16,764) | |

| % Susceptibility to meropenem | 87.0% (15,352) | 89.0% (16,730) | |

| % of carbapenemase | 1.92% (14,187) | 1.75% (14,094) | |

| % GES | 0.00% (12,212) | 0.00% (13,258) | |

| % NDM | 0.04% (13,782) | 0.04% (13,825) | |

| % VIM | 1.30% (13,925) | 1.63% (13,825) | |

| % of other carbapenemase | 0.08% (12,660) | 0.05% (13,258) | |

| % Susceptibility to ciprofloxacin | 75.8% (15,375) | 76.5% (17,116) | |

| % Susceptibility to amikacin | 95.7% (15,254) | 96.2% (17,026) | |

| % XDRc | 5.2% (14,091) | 4.9% (14,997) | |

| A. baumannii complex | % Susceptibility to carbapenems | 75.0% (256) | 86.7% (308) |

| % of carbapenemase | 1.3% (155) | 4.2% (261) | |

| S. aureus | % Susceptibility to ciprofloxacin | 75.5% (11,260) | 74.4% (14,183) |

| % Susceptibility to clindamycin | 76.0% (14,122) | 74.1% (16,236) | |

| % Susceptibility to cotrimoxazole | 97.1% (13,986) | 97.6% (16,219) | |

| % Susceptibility to daptomycin | 100% (11,338) | 100% (13,893) | |

| % Susceptibility to linezolid | 100% (13,927) | 100% (16,381) | |

| % Susceptibility to mupirocin | 93.6% (10,180) | 92.4% (13,473) | |

| % Susceptibility to vancomycin | 100.0% (14,213) | 100.0% (16,501) | |

| % MRSAd | 20.8% (14,419) | 22.1% (16,573) | |

| E. faecalis | % Susceptibility to ampicillin | 99.6% (14,315) | 99.8% (16,352) |

| % Susceptibility to ciprofloxacin | 70.8% (9665) | 74.1% (12,805) | |

| % Susceptibility to streptomycin (HLD)e | 73.3% (8155) | 73.7% (10,012) | |

| % Susceptibility to gentamicin (HLD)e | 71.2% (9361) | 76.4% (11,696) | |

| % Susceptibility to vancomycin | 99.9% (14,369) | 99.9% (16,257) | |

| E. faecium | % Susceptibility to ampicillin | 9.4% (4294) | 11.2% (4873) |

| % Susceptibility to streptomycin (HLD)e | 21.5% (2522) | 23.0% (3077) | |

| % Susceptibility to gentamicin (HLD)e | 78.8% (2871) | 80.7% (3443) | |

| % Susceptibility to teicoplanin | 99.0% (3732) | 98.7% (4582) | |

| % Susceptibility to vancomycin | 99.1% (4302) | 99.6% (4879) | |

| Coagulase-negative Staphylococci | % Susceptibility to ciprofloxacin | 51.9% (6955) | 53.0% (7603) |

| % Susceptibility to clindamycin | 54.0% (8762) | 57.1% (9839) | |

| % Susceptibility to cotrimoxazole | 69.1% (9067) | 71.8% (9551) | |

| % Susceptibility to daptomycin | 100% (6509) | 100% (8167) | |

| % Susceptibility to linezolid | 97.0% (8857) | 98.1% (10,010) | |

| % Susceptibility to rifampin | 88.8% (8278) | 88.7% (8795) | |

| % Susceptibility to teicoplanin | 90.9% (7537) | 88.4% (9204) | |

| % Susceptibility to vancomycin | 100% (9246) | 100% (10,137) | |

Table 5 displays the antibiotic susceptibility data for the primary pathogens causing UTIs in LTCFs. E. coli was isolated more than twice as frequently as K. pneumoniae, the second most common species. E. coli demonstrated high susceptibility to carbapenems, nitrofurantoin, and fosfomycin. Susceptibility to third-generation cephalosporins remained stable at 71.3%, while the proportion of ESBL-producing strains increased slightly to 25.8% in 2022. The prevalence of carbapenemase-producing strains was very low, with OXA-48 being the most common type identified. K. pneumoniae showed a slight decrease in susceptibility to carbapenems, dropping to 95.5% in 2022, and to third-generation cephalosporins, which fell to 53.9% over the same period. There was an increase in the production of ESBL, rising to 40.0%, and carbapenemase, increasing to 2.9%, with OXA-48 remaining the predominant type. Both E. coli and K. pneumoniae exhibited low susceptibility to fluoroquinolones and cotrimoxazole. P. aeruginosa, causing UTIs in LTCFs, showed a slight increase in susceptibility to fluoroquinolones, reaching 69.5% in 2022. The highest susceptibility rates were observed with amikacin and meropenem. Carbapenemase-producing strains remained low, with the majority being of the VIM type. The incidence of XDR strains remained below 2%.

Antimicrobial susceptibility among pathogens causing UTI in LTCF.

| Microorganism | Antibiotic attribute | Year 2021 | Year 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Total number of tested strains) | |||

| E. coli | % Susceptibility to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 61.7% (4156) | 62.3% (5267) |

| % Susceptibility to cefuroxime | 66.9% (3849) | 64.2% (4884) | |

| % Susceptibility to 3rd G. Cepha | 71.3% (4118) | 71.2% (5717) | |

| % ESBL-Pb | 24.2% (4064) | 25.8% (4916) | |

| % Susceptibility to carbapenems | 99.7% (3868) | 99.7% (4803) | |

| % of carbapenemases | 0.11% (3803) | 0.13% (4752) | |

| % IMP | 0.00% (3803) | 0.00% (4752) | |

| % KPC | 0.00% (3803) | 0.00% (4752) | |

| % NDM | 0.03% (3803) | 0.00% (4752) | |

| % OXA-48 | 0.03% (3803) | 0.13% (4752) | |

| % VIM | 0.05% (3803) | 0.00% (4752) | |

| % Susceptibility to quinolones | 53.5% (4125) | 53.1% (5751) | |

| % Susceptibility to fosfomycin | 94.2% (4139) | 93.4% (5204) | |

| % Susceptibility to cotrimoxazole | 63.9% (4097) | 64.9% (5197) | |

| % Susceptibility to nitrofurantoin | 96.7% (4101) | 96.5% (5225) | |

| K. pneumoniae | % Susceptibility to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 50.5% (1719) | 51.3% (2304) |

| % Susceptibility to cefuroxime | 53.4% (1636) | 48.6% (2216) | |

| % Susceptibility to 3rd G. Cepha | 56.1% (1698) | 54.0% (2556) | |

| % ESBL-P casesb | 36.5% (1664) | 40.0% (2287) | |

| % Susceptibility to carbapenems | 97.4% (1666) | 95.5% (2196) | |

| % of carbapenemases | 2.10% (32) | 2.95% (2272) | |

| % IMP | 0.00% (1523) | 0.00% (2228) | |

| % KPC | 0.20% (1523) | 0.04% (2228) | |

| % NDM | 0.00% (1523) | 0.22% (2228) | |

| % OXA-48 | 2.04% (1523) | 2.74% (2228) | |

| % VIM | 0.00% (1523) | 0.04% (2228) | |

| % Susceptibility to quinolones | 53.0% (1712) | 51.4% (2572) | |

| % Susceptibility to cotrimoxazole | 57.5% (1695) | 58.5% (2332) | |

| P. aeruginosa | % Susceptibility to imipenem | 77.8% (706) | 82.4% (943) |

| % Susceptibility to meropenem | 87.3% (755) | 88.5% (876) | |

| % of carbapenemases | 1.80% (666) | 1.35% (666) | |

| % KPC | 0.00% (664) | 0.00% (602) | |

| % NDM | 0.00% (664) | 0.17% (602) | |

| % OXA-48 | 0.00% (664) | 0.00% (602) | |

| % VIM | 1.51% (664) | 0.83% (602) | |

| % Susceptibility to quinolones | 64.4% (834) | 69.5% (1003) | |

| % Susceptibility to amikacin | 91.8% (429) | 92.3% (558) | |

| % XDR | 6.38% (705) | 5.43% (884) | |

| E. faecalis | % Susceptibility to ampicillin | 99.3% (990) | 99.6% (1125) |

| % Susceptibility to vancomycin | 99.6% (991) | 99.9% (1120) | |

| E. faecium | % Susceptibility to ampicillin | 4.3% (328) | 2.8% (327) |

| % Susceptibility to vancomycin | 99.7% (330) | 98.5% (323) | |

As expected, E. coli and K. pneumoniae have significantly more conserved antibiotic susceptibility in the community than in healthcare-associated isolates (hospital and LCTFs). If we compare hospital and LCTFs and include P. aeruginosa, the differences in susceptibility are also significant, except for carbapenem's susceptibility and the percentage of carbapenemases, both in Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa (Supplementary Table 4).

DiscussionOur study highlights recent trends and variability in antimicrobial resistance among essential microorganisms responsible for community-acquired and healthcare-associated infections in both children and adults across Catalonia's healthcare system. These findings are crucial, as they provide valuable data for developing and refining ASP initiatives, strengthening their strategic efforts to combat resistance.

The European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (EARSS), now integrated into the EARS-Net, is a key public health initiative coordinated by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).7 EARS-Net collects and analyzes data on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in key invasive (blood and cerebrospinal fluid) bacterial pathogens from clinical samples across European countries. The primary goal is to monitor AMR trends, compare data across countries, and support efforts to control and prevent the spread of resistant infections in Europe. In Spain, surveillance programs such as RENAVE and Catalonia's SNMC are essential for monitoring AMR. In contrast, the VINCat program further enhances antimicrobial stewardship efforts by providing targeted data on antibiotic prescriptions. The comparison between our data and the 2022 EARS-Net report for Spain in the hospital setting reveals several noteworthy findings that align with broader AMR trends across Europe.17

The challenge of addressing AMR in pediatric populations is compounded by the lack of surveillance programs that stratify susceptibility data by age and infection type. This gap makes it challenging to implement targeted prevention and control measures, considering the significant differences in resistance patterns between children and adults. UTIs are the second most common bacterial infection in pediatric care, often necessitating empirical antibiotic use. Studies indicate a troubling trend toward an increasing resistance to first-line antibiotics such as amoxicillin–clavulanic acid and cotrimoxazole for treating E. coli UTIs in children.18 This growing resistance has caused a shift in empirical treatment toward second- or third-generation cephalosporins or aminoglycosides, which have reported susceptibilities between 94–96%. The prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli is another concern, particularly given its increase in both, community and healthcare settings.19 This prevalence varies significantly by region, with studies reporting rates between 31% and 43% in Southeast Asia and Turkey, compared to less than 10% in Europe, the United States, and Australia. In our study, as regards E. coli, there was an increase in the percentage of ESBL E. coli in children in the community (2.9% vs. 3.8%) which was lower than that in the hospital (6.7%) and in adults in the community, hospital and LTCFs (9% vs. 12.8% vs. 25.8% respectively). Likewise, there was a decrease in susceptibility to amoxicillin–clavulanic acid in front E. coli in the pediatric population in the community (80.9%) and hospital (74.7%) as well as in adults in the hospital and LCTFs (71% and 62.3%, respectively). Something similar happens in quinolone susceptibility in adults, with a 76% susceptibility in the community, 71% in the hospital and 62% in LCTFs. The rise in E. cloacae complex strains resistant to third-generation cephalosporins due to AmpC β-lactamase hyperproduction is concerning and should be considered when treating healthcare-associated infections. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa in pediatric populations has increased. They mainly occur in children with risk factors, usually sporadic or in outbreak-associated cases.20 In the ARPEC European Surveillance Study, the prevalence of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae in blood cultures was higher in adults than in pediatrics (13.5% versus 6.5%) and higher than in our data (2.1% versus 0.5%, respectively).9 A Spanish nationwide study reported an XDR P. aeruginosa rate of 17.3%, with significant regional variation, but did not specify pediatric rates.21 In our pediatric series, the prevalence decreased, with isolates primarily from a tertiary care hospital specializing in cystic fibrosis care.

The proportion of MRSA in the pediatric population has remained stable or is declining in both, community and hospital settings. A Spanish study in eight pediatric emergency departments reported a 16.2% prevalence of community-acquired MRSA and 18.1% for healthcare-associated MRSA.22 These rates are higher than the 6.8% for community-acquired and 10% for hospitals and are more similar to that found in our study in hospital-acquired infections in adults (22%).

S. pyogenes can cause both invasive and non-invasive community infections in children. The treatment of choice is penicillin, which has stable susceptibility, but macrolides are still used empirically for outpatient respiratory infections. The SPIGAS study conducted between 2007 and 2019 on isolates from invasive infections reported 8.9% resistance to erythromycin and 4.3% to clindamycin.23 Our 2022 data show slightly higher resistance to both antibiotics. Globally, S. pneumoniae is the fourth leading cause of death associated with antibiotic resistance. In 2020, infections caused by influenza and respiratory syncytial virus dropped significantly, contributing to a decline in invasive pneumococcal infections, which explains the lower number of isolates in 2020. In our area, resistance to penicillin and macrolides has remained stable over the past three years and at levels lower than in Europe and the US.9,24

Regarding the adult population, the slightly higher resistance rates reported by EARS-Net in E. coli to third-generation cephalosporins (15% vs. 13% in our study) and carbapenems (0.6% vs. 0.1%) are consistent with the overall increase in AMR observed across European healthcare settings.17 These differences could be attributed to various factors such as differences in sample sources, patient populations, or regional variations in antibiotic prescribing practices. EARS-Net typically focuses on invasive isolates, which may represent more severe infections and could contribute to the higher resistance rates reported. For K. pneumoniae, the percentage of ESBL-producing strains (27% in EARS-Net vs. 20% in VINCat) and carbapenemase-producing strains (5% vs. 2%) underscores the ongoing challenges in managing multidrug-resistant organisms. Notably, other multicenter studies as CARB-ES and the RedLabRA reports, have also highlighted the presence of OXA-48 in K. pneumoniae, consistent with our findings.25,26 In P. aeruginosa, an overall decrease in resistance was reported between 2017 and 2022, along with a reduction in XDR strains, particularly in ICUs, while carbapenemase-producing strains have increased.27 The comparison of MRSA rates—26% in EARS-Net versus 22% in VINCat—suggests that MRSA remains a significant concern. Lastly, the lower vancomycin resistance observed in Enterococcus faecium is encouraging and reflects the low prevalence of this pathogen in Catalonian healthcare settings.

In primary care, quinolone-resistant E. coli causing UTIs was 31% in Spain in 2016, compared to 24% in Catalonia in 2022.28 Our lower level of quinolone resistance could suggest an improvement in the management of UTIs in the community, potentially due to more effective antimicrobial stewardship practices or changes in prescribing patterns. Regarding N. gonorrhoeae, the resistance to azithromycin and ciprofloxacin is concerning. A recent study from Spain reported 12.1% resistance to azithromycin and 56.2% to ciprofloxacin in 2019, while VINCat's 2020 data shows similar rates.29

Resistance rates in LTCFs are significantly higher than in community or acute care hospitals. These settings experience elevated antibiotic pressure, combined with clinical and environmental factors that promote the emergence and spread of multidrug-resistant organisms. Our data reflect this trend, showing a higher prevalence of ESBL-producing strains and increased resistance to most antibiotics monitored. It has been reported that elderly residents in LTCFs have a 40% higher risk of developing UTIs caused by resistant Enterobacterales compared to those living in the community.30 Colonization among LTCF residents is associated with a higher number of infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales. Similarly to other reports, our data show higher rates of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales in this population than in the community or acute care hospitals, with OXA-48 being the most frequently isolated.31 These observations underscore the critical need for targeted antimicrobial stewardship and infection control measures in LTCFs to mitigate the impact of resistant pathogens.

Finally, a major strength of our study is the use of centralized and comprehensive data across healthcare settings in Catalonia, which includes stratified information by age and type of healthcare setting, along with the high number of strains available analyzed. Our study has, however, some limitations. The short study period restricts the ability to observe long-term trends in antimicrobial resistance, as well as the detailed demographic and clinical information about the isolates was unavailable.

In conclusion, our data highlight the importance of providing stratified susceptibility reports based on setting, type of infection, and patient age to better support the efforts of ASP teams.

FundingThe VINCat Programme is supported by public funding from the Catalan Health Service, Department of Health, Generalitat de Catalunya.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availabilityRestrictions apply to the availability of these data, which belong to a national database and are not publicly available. Data was obtained from VINCat and are only available with the permission of the VINCat Technical Committee.

By alphabetical order: Alba Bellés Bellés, Albert Bernet Sánchez, Amaya Suárez López, Amparo García, Anna Llimós Fàbregas, Anna Padrós Fluvià, Anna Vilamala Bastarras, Antón Manonelles Fernández, Antonio Casabella Pernas, Araceli González-Cuevas, Ariadna Hernández Paraire, Carla Benjumea Moreno, Carles Alonso Tarrés, Carmen Ardanuy, Carme Gallés, Carme Mora Maruny, Carmen Pérez de Ciriza, Carmina Martí Sala, Clara Marco de Mas, Claudia Miralles Adell, Cristina Pitart Ferré, Damaris Berbel Palau, Duran Bellido, Eduardo Padilla León, Elisabet Folch, Emma Padilla Esteba, Ester Comellas Pujol, Ester del Barrio-Tofiño, Ester Moreno, Esther Clapés Sánchez, Esther Sanfeliu Riera, Eulàlia Jou Ferré, Fe Tubau Quintana, Fina Guimerà Vilamanyà, Francesc Marco, Frederic Ballester Basardie, Frederic Gómez Bertomeu, Gemma Flores Mateo, Gloria Trujillo Isern, Inés Valle T-Figueras, Isabel Puig Pey, Isabel Pujol Bajada, Ivan Prats, Ivett Suárez, Jaume Llaberia, Jessica Gálvez, Joan Galbany Padrós, Joana Padilla Lissens, Jordi Serra Álvarez, José Carlos De la Fuente, Juan Ayala Cervantes, Judith Lucena, Jun Hao Wang Wang, Laia Jou, Lluis Òscar Jorbà, Lourdes Montsant Montané, Maria Belen Viñado Pérez, Manel Panisello Bertomeu, Manuel Monsonís Cabedo, Mar Olga Pérez Moreno, María Alba Rivera Martínez, María Araceli González Cuevas, María Dolores Quesada Fernández, María Navarro Aguirre, Mariona Xercavins, Marisa del Pilar Martínez Maureso, Mayuli Armas Cruz, Mercè García González, Mercè Aguilar, Miguel Ángel Martínez López, Miquel Micó García, Mireia Iglesias, Mónica García, Montserrat Olsina, Natacha Recio Prieto, Núria Prim Bosch, Núria Torrellas Bertrán, Óscar Díaz, Paula Gassiot, Pep Ballester, Pepa Pérez Jové, Pilar Moga Vidal, Raquel Cliville Abad, Rosa Calsapeu, Rosa Laborda Gálvez, Rosa Rubio Casino, Rosalia Karine Santos da Silva, Sandra Esteban Cucó, Silvia Capilla Rubio, Tamara Soler, Teresa Falguera Sureda, Virginia Plasencia Miguel, Yannick Alan Hoyos Mallecot and Yuliya Poliakova.

The followings are the supplementary data to this article: