The frequency of use of systemic antifungal agents has increased significantly in most tertiary centers. However, antifungal stewardship has received very little attention. The objective of this article was to assess the knowledge of prescribing physicians in our institution as a first step in the development of an antifungal stewardship program. Attending physicians from the departments that prescribe most antifungals were invited to complete a questionnaire based on current guidelines on diagnosis and therapy of invasive candidiasis and invasive aspergillosis (IA).

The survey was completed by 60.8% (200/329) of the physicians who were invited to participate. The physicians belonged to the following departments: medical (60%), pediatric (19%), intensive care (15.5%), and surgical (5.5%). The mean (±SD) score of correct responses was 5.16±1.73. In the case of candidiasis, only 55% of the physicians clearly distinguished between colonization and infection, and 17.5% knew the local rate of fluconazole resistance. Thirty-three percent knew the accepted indications for antifungal prophylaxis, and 23% the indications for empirical therapy. However, most physicians knew which antifungals to choose when starting empirical therapy (73.5%). As for aspergillosis, most physicians (67%) could differentiate between colonization and infection, and 34.5% knew the diagnostic value of galactomannan. The radiological features of IA were well recognized by 64%, but only 31.5% were aware of the first line of treatment for IA, and 36% of the recommended duration of therapy. The usefulness of antifungal levels was known by 67%. This simple, easily completed questionnaire enabled us to identify which areas of our training strategy could be improved.

El uso de antifúngicos sistémicos se ha incrementado significativamente en los grandes hospitales. Sin embargo, la experiencia en el desarrollo de programas de optimización del uso de antifúngicos es muy limitada, pues la mayoría de los esfuerzos se han centrado en el control de los antibacterianos. El objetivo de nuestro estudio fue evaluar el conocimiento de los médicos prescriptores en el diagnóstico y tratamiento de las micosis invasivas en nuestra institución como parte de un programa de optimización del uso de antifúngicos. Se invitó a los médicos prescriptores de los distintos departamentos a completar un cuestionario de 20 preguntas cuya puntuación global fue de 0-10 puntos. Las preguntas se elaboraron de acuerdo a las recomendaciones de las guías de práctica clínica actuales para el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la candidiasis invasiva y la aspergilosis invasiva.

La tasa de respuesta fue de un 60,8% (200/329), de los cuales el 60% correspondió a departamentos médicos, 19% pediátricos, 15,5% unidades de críticos y 5,5% quirúrgicos. La puntuación media obtenida (± DS) fue 5,16 ± 1,73. Respecto a los conocimientos evaluados sobre candidiasis invasiva, un 45% de los médicos no fue capaz de distinguir entre colonización e infección, y solo el 17,5% conocía la tasa de resistencia local a fluconazol. Las indicaciones para profilaxis antifúngica y tratamiento empírico solo fueron correctamente identificadas por el 33% y el 23% de los médicos. Sin embargo, la mayoría identificaron correctamente el tratamiento empírico de elección (73,5%). Respecto a la aspergilosis invasiva, el 67% de los médicos diferenció correctamente colonización de infección y el 34,5% identificó la utilidad clínica de la detección del antígeno galactomanano. El diagnóstico radiológico de la aspergilosis invasiva fue correctamente evaluado por el 64% de los médicos, pero solo el 31,5% y el 36% identificaron correctamente el tratamiento de elección y su duración. La utilidad clínica de la monitorización de antifúngicos solo fue identificada correctamente por el 67% de los médicos. Un cuestionario como el propuesto en este trabajo permite identificar, de una forma ágil, las áreas de conocimientos que deben ser objetivo prioritario de una estrategia educativa dirigida a mejorar el uso de antifúngicos.

Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) are a major problem in tertiary care hospitals. They affect several types of patient and are cared for by several types of physician. The difficulties in confirming a diagnosis, the excellent tolerance of new drugs, and the impact of early therapy have led to extended use of empirical antifungal agents.

Previous studies, however, have shown that up to 67–74% of antifungal drugs are used inappropriately in tertiary care hospitals.1–3 A recent multicenter study performed in French intensive care units (ICU) revealed that 7% of all patients admitted on a single day were receiving antifungals, and 65% patients included had no proven IFI.4

International societies have recommended implementation of institutional antifungal stewardship programs.5 When antifungal costs surpassed €3 million and while our incidence of proven fungal infection remained stable, we decided to initiate an antifungal stewardship program that included training initiatives. We performed a knowledge survey in order to identify areas requiring specific attention.

Material and methodsSetting and participantsOur institution is a 1550-bed tertiary care hospital attending a population of 715,000 inhabitants. It is a referral center for solid organ transplantation, heart surgery, stem cell transplantation, and HIV-AIDS care.

Ours was a prospective study in which we invited 329 physicians to complete a questionnaire. Hospital areas were ordered according to spending on antifungals by the Pharmacy Department. The participating hospital departments were those that accounted for 85% of antifungal prescription. The participating physicians from these departments were given 15minutes to complete a brief questionnaire, which was then collected by one of the authors. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee.

QuestionnaireThe questionnaire was anonymous and included 20 multiple-choice questions on the diagnosis and management of IFIs (see Appendix B available online). We specifically included questions to identify inadequate indication of antifungals, such as the clinical interpretation of positive cultures or current recommendations for preemptive therapy. Each correct answer was scored as 0.5 points and each incorrect answer as 0 points (maximum score, 10 points).

The correct answer was selected by the steering committee of the Collaboration in Mycology Study Group of our institution (COMIC) according to current international guidelines.6,7

Statistical analysisOur endpoint was the median knowledge score obtained by physicians prescribing antifungals in our institution. We also decided to compare the performance of different groups of physicians (residents vs. staff physicians) and hospital departments (intensive care, pediatrics, medical, and surgical). Hematology and oncology were considered as medical departments.

Qualitative variables are reported with their frequency distribution. Quantitative variables are reported as the mean and SD and range (minimum-maximum). We used the t test or ANOVA to compare how scores differed according to the participants’ characteristics. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to detect differences in knowledge between different departments and types of physician after adjusting for sex and postgraduate education. Statistical significance was set at p≤0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® 16.0 and EPIDAT®.

ResultsThe questionnaire was completed by 200 of the 329 physicians invited to participate (60.8%; 115 staff [57.5%] and 85 residents [42.5%]). The percentage of responders was higher than 50% for all the departments involved, except for general surgery (40.8%), oncology (20.0%), and pneumology (12.5%). The distribution by departments was as follows: medical (including oncology and hematology) (60%), pediatrics (19%), intensive care unit (15.5%), and surgery (5.5%). The mean age of the responding physicians was 35.0±9.7 years, and 57% were women. Median duration of postgraduate training was 6 years (3.0–18.0).

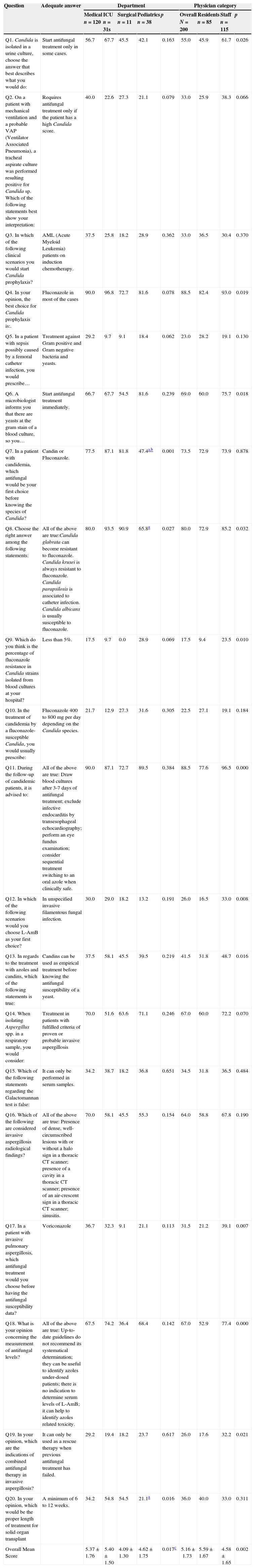

The overall mean score was 5.16±1.73 (ICUs, 5.40±1.50; medical wards, 5.37±1.76; pediatrics, 4.62±1.75; and surgery 4.09±1.30). The results of the survey by hospital department are shown in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were found between the different departments in the simple linear regression analysis; however, differences were found between the medical departments and the remaining departments after adjusting for sex, postgraduate training, and physician category (p=0.017) (Table 1).

Question and answers, percentage of adequate answers regarding department and physician category.

| Question | Adequate answer | Department | Physician category | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical n=120 | ICU n=31s | Surgical n=11 | Pediatrics n=38 | p | Overall N=200 | Residents n=85 | Staff n=115 | p | ||

| Q1. Candida is isolated in a urine culture, choose the answer that best describes what you would do: | Start antifungal treatment only in some cases. | 56.7 | 67.7 | 45.5 | 42.1 | 0.163 | 55.0 | 45.9 | 61.7 | 0.026 |

| Q2. On a patient with mechanical ventilation and a probable VAP (Ventilator Associated Pneumonia), a tracheal aspirate culture was performed resulting positive for Candida sp. Which of the following statements best show your interpretation: | Requires antifungal treatment only if the patient has a high Candida score. | 40.0 | 22.6 | 27.3 | 21.1 | 0.079 | 33.0 | 25.9 | 38.3 | 0.066 |

| Q3. In which of the following clinical scenarios you would start Candida prophylaxis? | AML (Acute Myeloid Leukemia) patients on induction chemotherapy. | 37.5 | 25.8 | 18.2 | 28.9 | 0.362 | 33.0 | 36.5 | 30.4 | 0.370 |

| Q4. In your opinion, the best choice for Candida prophylaxis is:. | Fluconazole in most of the cases | 90.0 | 96.8 | 72.7 | 81.6 | 0.078 | 88.5 | 82.4 | 93.0 | 0.019 |

| Q5. In a patient with sepsis possibly caused by a femoral catheter infection, you would prescribe… | Treatment against Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria and yeasts. | 29.2 | 9.7 | 9.1 | 18.4 | 0.062 | 23.0 | 28.2 | 19.1 | 0.130 |

| Q6. A microbiologist informs you that there are yeasts at the gram stain of a blood culture, so you… | Start antifungal treatment immediately. | 66.7 | 67.7 | 54.5 | 81.6 | 0.239 | 69.0 | 60.0 | 75.7 | 0.018 |

| Q7. In a patient with candidemia, which antifungal would be your first choice before knowing the species of Candida? | Candin or Fluconazole. | 77.5 | 87.1 | 81.8 | 47.4a,b | 0.001 | 73.5 | 72.9 | 73.9 | 0.878 |

| Q8. Choose the right answer among the following statements: | All of the above are true:Candida glabrata can become resistant to fluconazole. Candida krusei is always resistant to fluconazole. Candida parapsilosis is associated to catheter infection. Candida albicans is usually susceptible to fluconazole. | 80.0 | 93.5 | 90.9 | 65.8a | 0.027 | 80.0 | 72.9 | 85.2 | 0.032 |

| Q9. Which do you think is the percentage of fluconazole resistance in Candida strains isolated from blood cultures at your hospital? | Less than 5%. | 17.5 | 9.7 | 0.0 | 28.9 | 0.069 | 17.5 | 9.4 | 23.5 | 0.010 |

| Q10. In the treatment of candidemia by a fluconazole-susceptible Candida, you would usually prescribe: | Fluconazole 400 to 800mg per day depending on the Candida species. | 21.7 | 12.9 | 27.3 | 31.6 | 0.305 | 22.5 | 27.1 | 19.1 | 0.184 |

| Q11. During the follow-up of candidemic patients, it is advised to: | All of the above are true: Draw blood cultures after 3-7 days of antifungal treatment; exclude infective endocarditis by transesophageal echocardiography; perform an eye fundus examination; consider sequential treatment switching to an oral azole when clinically safe. | 90.0 | 87.1 | 72.7 | 89.5 | 0.384 | 88.5 | 77.6 | 96.5 | 0.000 |

| Q12. In which of the following scenarios would you choose L-AmB as your first choice? | In unspecified invasive filamentous fungal infection. | 30.0 | 29.0 | 18.2 | 13.2 | 0.191 | 26.0 | 16.5 | 33.0 | 0.008 |

| Q13. In regards to the treatment with azoles and candins, which of the following statements is true: | Candins can be used as empirical treatment before knowing the antifungal susceptibility of a yeast. | 37.5 | 58.1 | 45.5 | 39.5 | 0.219 | 41.5 | 31.8 | 48.7 | 0.016 |

| Q14. When isolating Aspergillus spp. in a respiratory sample, you would consider: | Treatment in patients with fulfilled criteria of proven or probable invasive aspergillosis | 70.0 | 51.6 | 63.6 | 71.1 | 0.246 | 67.0 | 60.0 | 72.2 | 0.070 |

| Q15. Which of the following statements regarding the Galactomannan test is false: | It can only be performed in serum samples. | 34.2 | 38.7 | 18.2 | 36.8 | 0.651 | 34.5 | 31.8 | 36.5 | 0.484 |

| Q16. Which of the following are considered invasive aspergillosis radiological findings? | All of the above are true: Presence of dense, well-circumscribed lesions with or without a halo sign in a thoracic CT scanner; presence of a cavity in a thoracic CT scanner; presence of an air-crescent sign in a thoracic CT scanner; sinusitis. | 70.0 | 58.1 | 45.5 | 55.3 | 0.154 | 64.0 | 58.8 | 67.8 | 0.190 |

| Q17. In a patient with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, which antifungal treatment would you choose before having the antifungal susceptibility data? | Voriconazole | 36.7 | 32.3 | 9.1 | 21.1 | 0.113 | 31.5 | 21.2 | 39.1 | 0.007 |

| Q18. What is your opinion concerning the measurement of antifungal levels? | All of the above are true: Up-to-date guidelines do not recommend its systematical determination; they can be useful to identify azoles under-dosed patients; there is no indication to determine serum levels of L-AmB; it can help to identify azoles related toxicity. | 67.5 | 74.2 | 36.4 | 68.4 | 0.142 | 67.0 | 52.9 | 77.4 | 0.000 |

| Q19. In your opinion, which are the indications of combined antifungal therapy in invasive aspergillosis? | It can only be used as a rescue therapy when previous antifungal treatment has failed. | 29.2 | 19.4 | 18.2 | 23.7 | 0.617 | 26.0 | 17.6 | 32.2 | 0.021 |

| Q20. In your opinion, which would be the proper length of treatment for solid organ transplant | A minimum of 6 to 12 weeks. | 34.2 | 54.8 | 54.5 | 21.1a | 0.016 | 36.0 | 40.0 | 33.0 | 0.311 |

| Overall Mean Score | 5.37±1.76 | 5.40±1.50 | 4.09±1.30 | 4.62±1.75 | 0.017c | 5.16±1.73 | 5.59±1.67 | 4.58±1.65 | 0.002 | |

When the percentage of correct answers for each question was compared by department, statistical differences were found in 3 questions (Table 1). Unlike physicians from medical departments, the ICU, and surgical departments, more than half of the pediatricians responded incorrectly that L-AmB was the treatment of choice for candidemia before the species of Candida is identified, instead of fluconazole or a candin. Pediatricians were also more commonly unaware of the particularities of non-albicans Candida species and the correct length of therapy for invasive aspergillosis (IA). Statistical differences were only detected between the pediatrics department and the medical departments.

Comparison of the mean scores between the different categories of physicians revealed that staff (5.59±1.67) had better results than residents (4.58±1.65) (p<0.001). The multiple linear regression analysis showed statistical differences between both categories (p=0.002). The staff performed better (higher percentage of correct answers) than the residents in 11 out of 20 questions (Table 1).

Finally, most participants (84%) reported that they would be willing to take an online course to update their knowledge of antifungal therapy. Only 12% were not interested, and 4% of the physicians did not answer this question.

CandidiasisA relatively low percentage of physicians clearly distinguished infection from urinary tract colonization (55%) and respiratory tract colonization (33% [patients with suspected VAP]). The accepted indications for antifungal prophylaxis were known by 33%. However, most physicians (88.5%) knew that the recommended antifungal agent for prophylaxis was fluconazole in most cases.

Regarding empirical therapy, only 23% of physicians were aware of the recommendation to initiate antifungal therapy in a patient with sepsis and a femoral catheter as the suspected portal of entry. However, when considering starting empirical therapy, 73.5% of physicians chose the correct/recommended antifungal. As for targeted therapy, 69% started treatment immediately once they were aware a yeast had been recovered from blood culture.

Most prescribing physicians (80.0%) were able to identify the specific characteristics of non-albicans Candida species, including their potential for azole resistance. In addition, 88.5% recognized the need to consider infectious endocarditis and endophthalmitis in a patient with candidemia and the importance of obtaining blood cultures during follow-up in order to rule out persistent candidemia and treatment failure.

Only 22.5% of the physicians knew the correct dosage of fluconazole (800mg as a loading dose followed by 400mg/d); only 17.5% knew the local rate of fluconazole resistance (it was generally overestimated).

Finally, with regard to the different indications for liposomal amphotericin B (L-AmB), azoles, or candins, our questionnaire revealed that only 26.0% of physicians knew when to prescribe L-AmB as the first choice in unspecified IFIs. Clinicians tended to consider L-AmB the treatment of choice for IA (30.0%) and for infections caused by fluconazole-resistant Candida species (26.5%). Forty-one percent answered correctly that candins could be used as empirical treatment of candidemia before antifungal susceptibility is known, and 27% preferred voriconazole to candins when treating infections due to fluconazole-resistant Candida.

Invasive aspergillosisSixty-seven percent of physicians correctly differentiated colonization from infection. More than half (64%) recognized the radiological features of IA, but only 34.5% were acquainted with the galactomannan test as a diagnostic tool and its value for follow-up.

Only 31.5% of the physicians were aware that voriconazole was the first-line IA treatment according to the latest guidelines. Some physicians believed that the combinations of L-AmB and voriconazole (17%) or voriconazole and caspofungin (16.5%) were acceptable as first-line therapy for treating IA. In addition, some physicians did not seem to know the correct dose of L-AmB and still considered that 10 mg/kg (instead of 3 mg/kg) was the adequate dose, ignoring the current guidelines.7

When asked specifically about the indications for combination treatment of IA, 51.5% considered this approach necessary when treating neutropenic or transplant recipients, and 26% only for rescue therapy. More than half of the physicians (67%) were aware of the clinical benefits of measuring voriconazole and posaconazole plasma levels during treatment. Finally, the recommended duration of therapy for IA according to current guidelines was only known by 36% of the physicians: 38% wrongly considered that 4 to 6 weeks was enough to treat most IA episodes.

DiscussionOurs is the first study to evaluate knowledge of current recommendations on diagnosis and treatment of IFI in a tertiary hospital with a very high consumption of systemic antifungal drugs. We demonstrated that even frequent prescribers have a significant need for continuing medical education in this area. The most common mistakes led to overconsumption of antifungal drugs, since many physicians prescribe combinations and high doses of L-AmB, as well as inappropriate treatment for fungal colonization. The physicians questioned welcomed the possibility of a custom training program.

The results from the questionnaire we present reveal gaps in both diagnosis and management of IFI in our institution. The most critical aspects for intervention are discussed below.

First, physicians sometimes find it difficult to distinguish between colonization and infection when Candida species is isolated in urine or in a tracheal aspirate. Consequently, the potential for overprescription of antifungal therapy is considerable.

Second, poor knowledge of the indications for antifungal prophylaxis and empirical treatment means that almost 50% of physicians would initiate Candida prophylaxis in an ICU patient colonized by Candida species, an ICU patient with a urinary catheter, an ICU patient with a central venous catheter, and a patient who has recently undergone surgery, without taking into consideration other risk factors. Although at least 8 clinical trials involving several types of ICU and surgery patients have demonstrated that prophylaxis with fluconazole can reduce the frequency of invasive candidiasis by around 50% and improve mortality,8–12 this strategy remains inefficient unless it targets high-risk patients13 and could lead to an increase in the frequency of subsequent azole-resistance and non-albicans candidemia.14–16 According to the latest guidelines,6 antifungal prophylaxis is only warranted in ICU patients who are at the highest risk of invasive candidiasis (>10%).17

Third, almost 80% of physicians failed to identify the indication for antifungal therapy in a patients with sepsis possibly caused by a femoral catheter infection, as recommended in the latest guidelines for the management of catheter-related infections.18 Furthermore, 30% would have delayed antifungal treatment after being informed of positive blood cultures, even though the critical window of opportunity for initiation of therapy is 12–24h after the first positive blood culture.19,20

Fourth, since most physicians were not aware of the relatively low incidence of azole resistance in Candida in our institution, they tended to prescribe more broad-spectrum antifungals. Although non-albicans strains are clearly more frequent, the rate of fluconazole resistance in most European centers is still less than 5%.21–23 It is also noteworthy that 26.5% of physicians would choose L-AmB and 27.5% voriconazole instead of a candin to treat fluconazole-resistant Candida infections. In our opinion, L-AmB should be restricted to cases of intolerance to other antifungal agents owing to its potential for toxicity and higher cost, and voriconazole should be limited to oral step-down therapy for selected cases of candidiasis due to voriconazole-susceptible C. krusei or C. glabrata.6

Finally, physicians often did not know the appropriate fluconazole dosage for treatment of Candida infections. Failure to achieve pharmacodynamic targets for fluconazole has been associated with worse outcomes.24–27 Dosing should aim to achieve target AUC/MIC ratios of at least 25 (based on Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute MIC methodology)28 or 100 (based on European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing MIC methodology) to maximize the probability of clinical success; these targets usually require 6mg/kg/d (following a 12mg/kg loading dose) for susceptible isolates or 12mg/kg/d for C. glabrata or other isolates with MICs of 16–32mg/L, as recommended in the latest guidelines.6

Problems differentiating colonization from infection were also evident for invasive aspergillosis. In a previous study, only 22.3% of Aspergillus isolates in our institution corresponded to cases of probable/proven invasive aspergillosis. We proposed a prediction score that took into account the procedure used to obtain the sample, the presence of leukemia or neutropenia, and the use of corticosteroids to help clinicians in the interpretation of Aspergillus cultures.29 The use of this score could help physicians in cases where colonization has to be excluded.

Furthermore, a high percentage of the prescribing physicians still considered L-AmB as first-line therapy, whereas the largest prospective, randomized trial for the treatment of invasive aspergillosis demonstrated that voriconazole was superior to amphotericin B deoxycholate and is also considered the first-choice antifungal in international guidelines.7,30–33 The role of combination therapy as primary or salvage therapy is uncertain and warrants evaluation in a prospective, controlled clinical trial. However, many physicians consider combination therapy to be standard of care. Guidelines clearly recommend it as an approach in patients who do not respond to voriconazole or L-AmB.7

Most physicians did not know that current guidelines recommend that treatment of invasive aspergillosis be continued for a minimum of 6–12 weeks and that voriconazole plasma levels be monitored during treatment to avoid toxicity and therapeutic failure.34

Finally, we found differences in knowledge between experienced physicians and residents. As expected, hematologists and infectious diseases specialists were more knowledgeable about prescription of antifungal therapy in our institution, since they treat the largest number of patients with IFIs.

Our study is subject to 2 main limitations. First, we only assessed the knowledge of those physicians who most frequently prescribe antifungal agents: the results could have been worse if all the physicians in the institution had participated. Second, the questionnaire addressed only invasive Candida and Aspergillus infections, and knowledge of other non-invasive fungal infections and of fungal infections caused by other agents was not assessed.

Our questionnaire can be used to assess basic knowledge of antifungal therapy among antifungal prescribers in a single institution. Baseline assessment of knowledge should be part of antifungal stewardship bundles and enables us to evaluate the impact of training initiatives. The results obtained would highlight which areas, professionals, and units are amenable to intervention. However, training without an active intervention is only marginally effective in changing antimicrobial prescribing practices. Other strategies that can be implemented include the following: (i) prospective audit of antifungal use involving direct interaction with and feedback to the prescriber, with emphasis on improving the use of broad-spectrum and costly antifungals; (ii) definition and tracking of process and outcome measures in order to determine the impact of interventions, for example, a point score that evaluates the appropriateness of each antifungal prescription, the percentage of recommendations accepted, mortality attributable to IFI, incidence of adverse drug events [grade III–IV], antifungal consumption [defined daily dose], and the incidence of azole-resistant Candida infections); (iii) implementation of computerized physician order entry with clinical decision support that improves decisions on antifungal therapy through the incorporation of local guidelines and data on patient-specific microbiology cultures, liver and kidney function, drug–drug interactions, allergies, and cost. In our opinion, infectious diseases specialists and clinical pharmacists should work together to control hospital infection. The pharmacy and therapeutics committee must also play a key role, with the support of the hospital administration and medical staff management.

ConclusionsA simple test enabled us to assess the knowledge of prescribing physicians about important aspects of the diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment of IFIs. Our results revealed serious gaps that require a custom training program that could act as the first step in the implementation of an antifungal stewardship program.

FundingThis study was partially financed by PROMULGA Project (Proyecto Multidisciplinar para Optimizar la Gestión del Uso de Antifúngicos). Instituto de Salud Carlos III. PI1002868.

Rafael Bañares, Emilio Bouza, Amaya Bustinza, Betsabé Cáliz, Pilar Escribano, Ana Fernández-Cruz, Lorenzo Fernández-Quero, Isabel Frias, Jorge Gayoso, Jesús Guinea, Javier Hortal, Maricruz Menárguez, Maria del Carmen Martínez, Iván Márquez, Patricia Muñoz, Belén Padilla, Belén Pinilla, Teresa Peláez, José Peral, Carmen Guadalupe Rodríguez, Diego Rincón, Maria Magdalena Salcedo, Mar Sánchez-Somolinos, Maria Sanjurjo, David Serrano, Maricela Valerio, Eduardo Verde and Elena Zamora.