A structured surveillance study was conducted on children with diarrhea who were hospitalized in Madrid (Spain) during 2010–2011, in order to describe temporal, geographic, and age-related trends in rotavirus (RV) strains after the introduction of the RV vaccines in our country.

Study design and resultsA total of 370 children were enrolled, with RV being detected in 117 (31.6%) cases. Coinfections were detected mainly with rotavirus, astrovirus and norovirus. The most prevalent rotavirus G type was G1 (60.7%) followed by G2 (16.09%), G9 (5.9%), and G12 (5.1%). The G12 genotype appeared for the first time in 2008 in Spain, and it has increased to 5.1% of the cases in this report. Some uncommon P genotypes, such as P[14] and P[6], both with a low percentage, were found. The samples with G1 G2, G9 and G12 genotypes appeared in all ages, but were significantly higher in children under 2 years old.

ConclusionA long-term structured surveillance is required in the Spanish post vaccine era, in order to determine the prevalence and variability of RV genotypes. This will especially be needed to distinguish between changes occurring as a result of natural fluctuation in genotype or those (changes) that could be mediated by population immunity to the vaccines. In addition, it will be necessary to study the impact of the current vaccines on the circulating rotavirus strains and on the overall reduction in the prevalence of rotavirus disease among children in Spain.

durante el período 2010-2011 se llevó a cabo un estudio de vigilancia entre los niños con diarrea que fueron hospitalizados en Madrid (España), con el fin de describir los genotipos circulantes de rotavirus (RV) después de la introducción de las vacunas en nuestro país.

Método y resultadosUn total de 370 niños fueron incluidos en el estudio. RV se detectó en 117 (31.6%) casos. Las coinfecciones detectadas fueron rotavirus, astrovirus y norovirus. El genotipo más prevalente fue G1 (60.7%) seguido de G2 (16.09%), G9 (5.9%) y G12 (5.1%). G12 apareció por primera vez en 2008 en España y ha aumentado hasta el 5.1% de los casos en este estudio. Algunos genotipos P infrecuentes como P[14] y P[6], fueron identificados, ambos con un porcentaje bajo. G1,G2, G9 y G12 se aislaron en todas las edades, pero son significativamente más frecuentes en los niños menores de 2 años de edad.

ConclusiónCon el fin de conocer la prevalencia y variabilidad de los genotipos de RV, la vigilancia a largo plazo será necesaria en la era postvacunal. Esta será especialmente necesaria para distinguir entre cambios que se producen como resultado de la fluctuación natural del genotipo o los cambios que podrían estar mediados por inmunidad de la población a las vacunas. Además, será necesario estudiar el impacto de las vacunas actuales sobre las cepas de rotavirus circulantes y en la reducción global de la prevalencia de la enfermedad por rotavirus en nuestro país.

Rotavirus has been considered a universal infection of early childhood and each year causes approximately 2 million hospitalizations with dehydration worldwide.1,2 Global data show that diarrhea attributable to Rotavirus (RV) infection resulted in 453,000 deaths yearly in children younger than 5 years.3–5

Group A rotavirus is subdivided into distinct G and P genotypes with a great diversity of RV strains cocirculating in human population throughout the world. Globally the most common genotypes of RV group A which cause acute gastroenteritis (AGE) in infants and young children were G1P[8], G2P[4], G3P[8] and G4P[8], and G9P[8]. However, the prevalence of RV genotypes might vary considerably according to location and time.6,7

Diarrhea remains as an important cause of morbidity among infants and young children in Spain. Our previous reports throughout Spain over several years showed a genotype shift over time.7,8 G1P[8] and G4P[8] were the predominant cocirculating strains from 1996 to 2004.8,9 A major shift during 2005/2006 period took place and the predominant detected strains were G9P[8] and G3P[8].7 However, during the 2006/2008 period a decrease of incidence of genotype G9P[8] and an increase of G1P[8] were noted.10 Other Spanish studies indicated similar shifts in the prevalence of RV genotypes including the G12.11,12

RV vaccines (RotaTeq®, Sanofi-Pasteur. MSD and Rotarix®, GlaxoSmithKline) were licensed in Spain in early 2007.13,14 However, to date, Rotavirus vaccination is not reimbursed by the Spanish National Health System.15 In addition, the Spanish Medicines and Health Products Agency (AEMPS) did not authorize the release of new batches of Rotarix® and RotaTeq® vaccines onto the Spanish market between March 29 and June 10, 2010. This was due to the finding of fragments of circovirus DNA. Nevertheless, on November 4, 2010 the only RV vaccine permitted by AEMPS was RotaTeq® that currently is the only RV vaccine allowed in Spain.16,17

ObjectivesWe report here the results of the prevalence, as well as genetic characterization of RV from the period 2010 to 2011. We describe here the temporal, geographic, and age-related trends in RV strains in Spanish children hospitalized in Madrid, after the introduction of the RV vaccines in our country.

Study designSince 1996 a surveillance collaborating study has been established by the Viral Gastroenteritis Unit, Centro Nacional Microbiología (ISCIII, Madrid, Spain) and Severo Ochoa University Hospital (Madrid, Spain).6–9 The Severo Ochoa Hospital is the reference sanitary hospital of South West Health Area II of Madrid serving a population <5 years of 10,253 inhabitants.18

Stool samples were collected from children with AGE hospitalized in the Severo Ochoa University Hospital. The study was conducted all the year round from January 1st 2010 to December 31st 2011, and included children <5 years of age with AGE Epidemiological and patient data (age, sex, date of sample collection) were collected using ad hoc questionnaires and entered into a database for linkage to the RV genotyping data. Patient's privacy and confidentiality issues were managed in full agreement with national legislation.

AGE was defined as >3 looser-than normal stools within a 24-h period or an episode of forceful vomiting and any loose stool. Children presenting with chronic diarrhea, immune deficiency, inflammatory disease of the digestive tract, or nosocomial infections were excluded.

Stool specimens were collected and transported immediately to hospital laboratory, and stored at 4°C until processing. All fecal samples were screened for enteropathogenic bacterial agents by conventional culture methods as previously described.7 Each week specimens were sent to the reference laboratory (ISCIII, Madrid, Spain). A 10% suspension in 0.1mol/L phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2) was prepared and tested by reverse transcription (RT-PCR) for rotavirus, astrovirus, norovirus, and enteric adenoviruses.7

Viral RNA was extracted from 140 μL of the 10% fecal suspension by using a commercial kit (QIAamp viral RNA minikit; QIAGEN GmbH, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was eluted in 60μL of RNA-free distilled water and stored at –80°C. Rotavirus G and P were typed by using RT-PCR methods as previously reported.6–8 Rotavirus amplicons were genetically characterized by nucleotide sequencing of both strands of the amplified PCR products when necessary as previously described.7

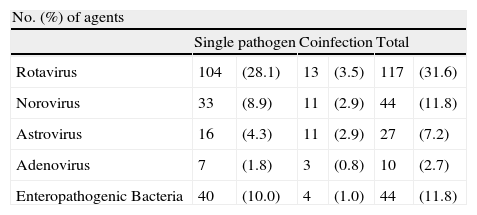

ResultsFrom 1st January 2010 to 31 December 2011, a total of 370 children were enrolled [<1 year old (97children), 1–2 years old (209 children) and 3–4 years old (64 children]. Enteropathogenic bacterial strains were detected in 44 (11.8%) cases. Norovirus were also found in 44 (11.8%) cases followed by astrovirus 27 (7.2%) and adenovirus 10 (2.7%) cases (Table 1).

Incidence of etiological agents detected in children <5 years old hospitalised with acute gastroenteritis during 201–2011 in Madrid, Spain.

| No. (%) of agents | ||||||

| Single pathogen | Coinfection | Total | ||||

| Rotavirus | 104 | (28.1) | 13 | (3.5) | 117 | (31.6) |

| Norovirus | 33 | (8.9) | 11 | (2.9) | 44 | (11.8) |

| Astrovirus | 16 | (4.3) | 11 | (2.9) | 27 | (7.2) |

| Adenovirus | 7 | (1.8) | 3 | (0.8) | 10 | (2.7) |

| Enteropathogenic Bacteria | 40 | (10.0) | 4 | (1.0) | 44 | (11.8) |

A total of 117 (31.6%) rotavirus strains were detected. Rotavirus was found alone in 104 (28.1%) samples but was found in another 13 (3.5%) samples as a coinfection (Table 1). The most common association was rotavirus and astrovirus in 9 out of the 13 confections.

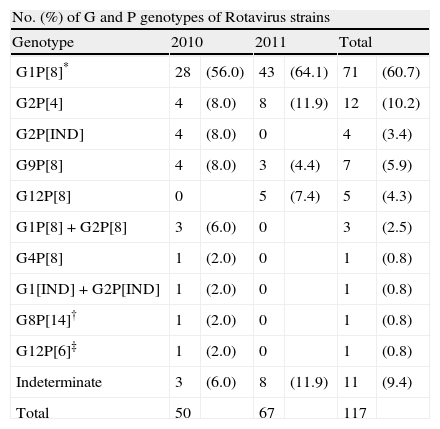

G and P typing RT-PCR for rotavirus were performed on the 117 samples positive. Of them 105 (89.7%) were fully characterized strains. However, G or P genotype could not be identified in 12 samples (10.2%). The most predominant was G1 (60.7%) followed by G2 (16.1%) G9 (5.9%) and G12 (5.1%). G4 was poorly found during this study and G3, previously reported as a common type in Spain,7 was not found (Table 2).

G and P genotypes of Rotavirus strains from Madrid, Spain through 2010–2011.

| No. (%) of G and P genotypes of Rotavirus strains | ||||||

| Genotype | 2010 | 2011 | Total | |||

| G1P[8]* | 28 | (56.0) | 43 | (64.1) | 71 | (60.7) |

| G2P[4] | 4 | (8.0) | 8 | (11.9) | 12 | (10.2) |

| G2P[IND] | 4 | (8.0) | 0 | 4 | (3.4) | |

| G9P[8] | 4 | (8.0) | 3 | (4.4) | 7 | (5.9) |

| G12P[8] | 0 | 5 | (7.4) | 5 | (4.3) | |

| G1P[8]+G2P[8] | 3 | (6.0) | 0 | 3 | (2.5) | |

| G4P[8] | 1 | (2.0) | 0 | 1 | (0.8) | |

| G1[IND]+G2P[IND] | 1 | (2.0) | 0 | 1 | (0.8) | |

| G8P[14]† | 1 | (2.0) | 0 | 1 | (0.8) | |

| G12P[6]‡ | 1 | (2.0) | 0 | 1 | (0.8) | |

| Indeterminate | 3 | (6.0) | 8 | (11.9) | 11 | (9.4) |

| Total | 50 | 67 | 117 | |||

* Eight out of 71 samples correspond to mixed infections.

†,‡ Coinfection with astrovirus.

IND – Indeterminate.

In this period the most prevalent genotype was G1, but it could be noted that the proportion of the G2 was 24% in 2010 and 11.9% in 2011 (p>0.5). G12 genotype that appeared in Spain for first time in 200810 increased from one case in 2010 to 5 (5.1%) cases in 2011 (Table 2).

The most common P type was P[8] (76%) followed by P[4] (10.2%). In this study few uncommon P genotypes as P[14] and P[6] both with a percentage of 0.8% were found.

Common G/P combinations as well as infrequent patterns and mixed-infection were detected (Table 2). G1P[8] (60.7%), G2P[4] (10.2%) and G9P[8] (5.9%) were the most common combinations, but G12P[8] (4.3%), G12P[6] (0.8%) and G8P[14] (0.8%) were detected as unusual combinations (Table 2).

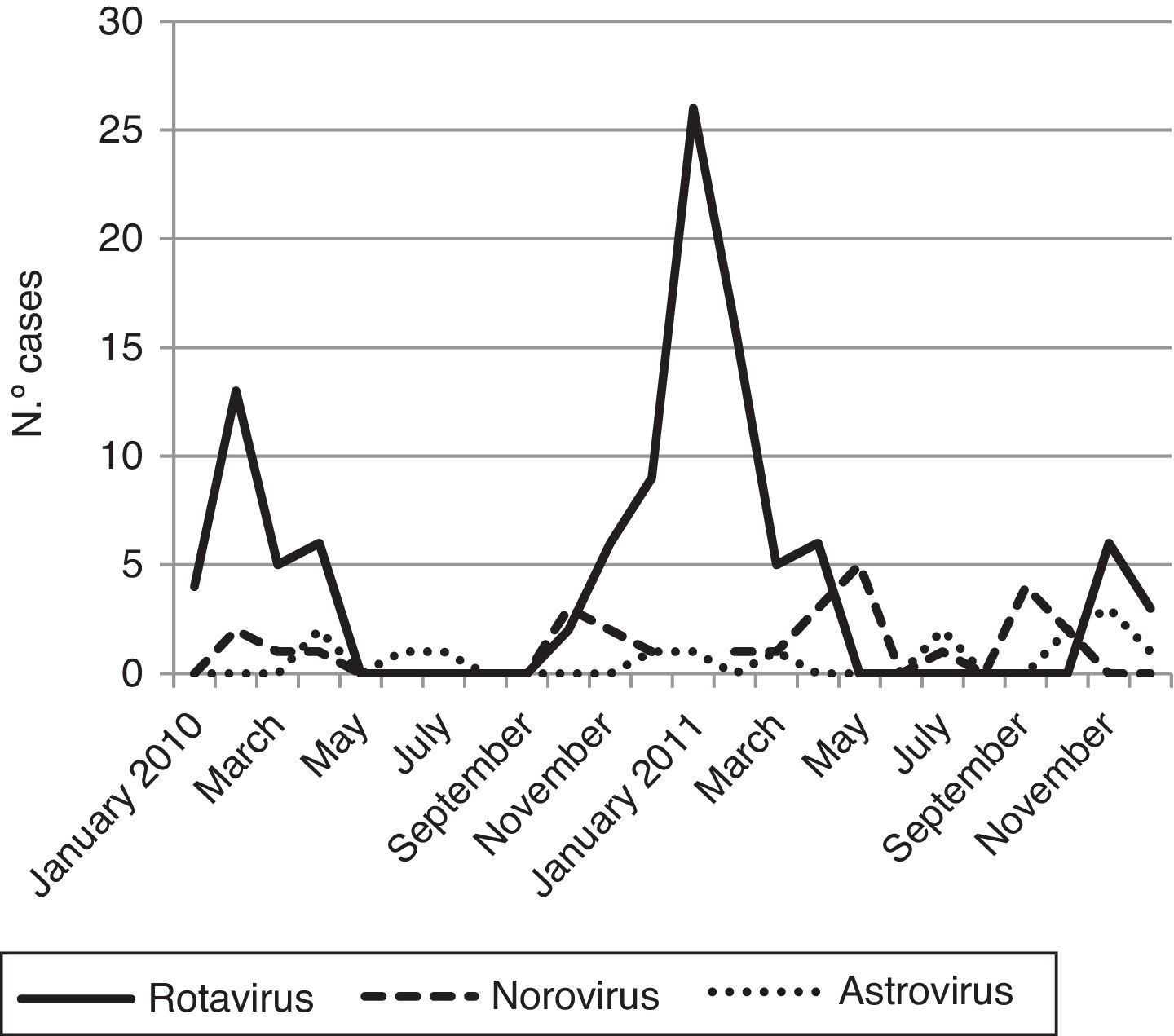

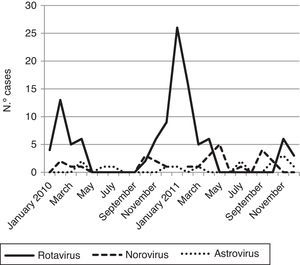

Viral diarrhea occurred year-round but was predominant in winter. The RV infection reached one clear peak in January 2011 and the norovirus infections reached two peaks; the first one was in May 2011 and the second in September 2011 (Fig. 1).

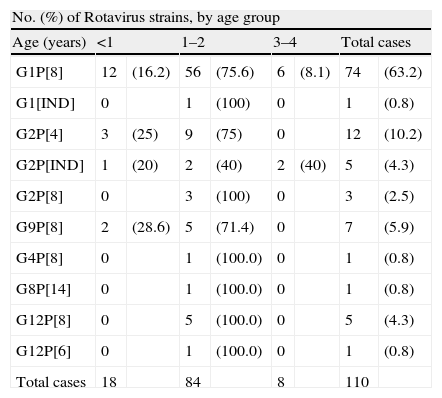

Of the 117 Rotavirus positive 62.6% (82 cases) were male and 37.4% (35 cases) female. The median age of children with RV acute gastroenteritis were 12 months, with a mean age of 16.4 months. The distribution of rotavirus genotypes and age is shown in Table 3.

Distribution of G and P rotavirus genotypes by age group.

| No. (%) of Rotavirus strains, by age group | ||||||||

| Age (years) | <1 | 1–2 | 3–4 | Total cases | ||||

| G1P[8] | 12 | (16.2) | 56 | (75.6) | 6 | (8.1) | 74 | (63.2) |

| G1[IND] | 0 | 1 | (100) | 0 | 1 | (0.8) | ||

| G2P[4] | 3 | (25) | 9 | (75) | 0 | 12 | (10.2) | |

| G2P[IND] | 1 | (20) | 2 | (40) | 2 | (40) | 5 | (4.3) |

| G2P[8] | 0 | 3 | (100) | 0 | 3 | (2.5) | ||

| G9P[8] | 2 | (28.6) | 5 | (71.4) | 0 | 7 | (5.9) | |

| G4P[8] | 0 | 1 | (100.0) | 0 | 1 | (0.8) | ||

| G8P[14] | 0 | 1 | (100.0) | 0 | 1 | (0.8) | ||

| G12P[8] | 0 | 5 | (100.0) | 0 | 5 | (4.3) | ||

| G12P[6] | 0 | 1 | (100.0) | 0 | 1 | (0.8) | ||

| Total cases | 18 | 84 | 8 | 110 | ||||

Rotavirus genotype G1 was present in the samples from children of all ages, but genotypes G2, G9 and G12 were more frequently found (p>0.5) in children younger than 2 years. Rotavirus infections in children 3 and 4 years old were infrequently found in this series (Table 3).

DiscussionDuring the pre-vaccine era in Spain, different studies have identified G1P[8] as the predominant circulating strains from 1996 to 2004, with a major shift during 2005/06 period when the predominance of G9P[8] and G3P[8] strains were observed.7–10 One of the most consistent findings in this study was the very high prevalence of the globally common genotypes G[1] and P[8] during the entire period of surveillance. Our 63% detection rate is higher than in previous season that was 49.8%.10 Similar prevalence was reported in previous studies in other areas of the world.19–21

Although we found a high overall prevalence of G1P[8], other strains such as G2P[4], G2P[8] and G9P[8] have been detected. Several uncommon G and P genotypes as G12P[6] and G8P[14] with a very low frequency (0.8%) were detected as unusual combinations.

Of note, the recently emerged genotype G12 appeared for the first time in Spain during 200810 and it had a prevalence of 5.1% in 2011. This result is consistent with that found in another recent Spanish study that reported that G12 was the predominant G type during 2011 in the Basque country.22 These results suggest that G12 might be a potential emerging genotype in Spain in the near future.

In contrast, another common strain, genotype G4P[8] was infrequently detected throughout the surveillance period and G3 was not found at all. Overall, these results are similar to those of other surveillance studies conducted worldwide.6,23,24

Some differences were observed in the proportions of certain genotypes among age groups. Genotype G1P[8] was more often found in all age groups. Interestingly, G2P[4] and G12P[8] strains were only observed in children under 2 years old. The highest prevalence and the most uncommon genotypes have been found in children between 1 and 2 years coinciding with other studies.25,26,22 The sample size of the oldest group was probably too small, with only 8 cases, to be representative.

Rotavirus gastroenteritis can now be prevented by vaccination with two vaccines (RotaTeq®, and Rotarix®) licensed in more than 100 countries worldwide.23 However, as it has been mentioned before, only RotaTeq® is available in Spain.17

Of note, G1 had increased its percentage during the period of time when the rotavirus vaccines were not available in Spain.16 More evidence needs to be gathered in order to come to firm conclusions.

In order to know the prevalence and variability of RV genotypes, a long-term structured surveillance will be necessary in the Spanish postvaccine era. In addition, it will be necessary to study the impact of the current vaccines on the circulating rotavirus strains and on the overall reduction in the prevalence of rotavirus disease among children in Spain.

FundingInstitutional.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

We thank Dr. R Glass for his unending support.