People with HIV (PWH) often exhibit vitamin D deficiency, with ambiguous treatment guidelines. This study evaluates the effectiveness of three vitamin D3 calcifediol supplementation regimens over 48 weeks, aiming to identify patients whose serum levels do not increase above 20ng/mL.

MethodsIn this prospective observational study, 112 HIV-positive outpatients with 25OHD levels below 20ng/mL were assigned to one of three supplementation groups. Group 1 received 16,000IU weekly for 12 weeks, then biweekly; Group 2 received 180,000IU every 12 weeks; Group 3 received 180,000IU every 4 weeks for the first 12 weeks, then every 12 weeks. The groups were compared using ANOVA and Chi-squared tests.

ResultsThe average participant age was 51.59 years, with 71.4% being male, all on antiretroviral therapy for an average of 9.5 years. By week 48, Group 1 showed the lowest percentage of patients with levels below 20ng/mL (10.2%), significantly outperforming Group 2 (44%) and Group 3 (31.6%). Vitamin D levels significantly increased in Groups 1 and 3, with no significant change in calcium, phosphorus and bone density between groups. The CD4:CD8 ratio increased significantly in all groups. No side effects were observed.

ConclusionsThe regimen of 16,000IU calcifediol weekly for 12 weeks followed by biweekly dosing is both safe and effective for PWH, significantly increasing vitamin D levels and improving the CD4:CD8 ratio without adverse effects.

Las personas que viven con el VIH (PVIH) a menudo presentan deficiencia de vitamina D, y no existe uniformidad en las guías de tratamiento. Este estudio evalúa la efectividad de 3 regímenes de suplementación con calcifediol vitamina D3 durante 48 semanas, con el objetivo de identificar a los pacientes cuyos niveles séricos no superan los 20ng/ml.

MétodosEstudio observacional prospectivo en el que se incluyeron 112 PVIH con niveles de 25OH vitamina D por debajo de 20ng/ml. Fueron asignados a uno de 3 grupos de suplementación con calcifediol. El Grupo 1 recibió 16.000UI semanales durante 12 semanas, posteriormente cada 2 semanas; el Grupo 2 recibió 180.000UI cada 12 semanas; el Grupo 3 recibió 180.000UI cada 4 semanas durante las primeras 12 semanas y posteriormente, la misma dosis cada 12 semanas. Se compararon los grupos utilizando ANOVA y pruebas de Chi-cuadrado.

ResultadosLa edad promedio de los participantes fue de 51,59 años, con un 71,4% de varones, todos en terapia antirretroviral durante un promedio de 9,5 años. En la semana 48, el Grupo 1 mostró el menor porcentaje de pacientes con niveles por debajo de 20ng/ml (10,2%), superando significativamente al Grupo 2 (44%) y al Grupo 3 (31,6%). Los niveles de vitamina D aumentaron significativamente en los Grupos 1 y 3, sin cambios significativos en calcio, fósforo y densidad mineral ósea entre los grupos. El cociente CD4:CD8 aumentó significativamente en todos los grupos. No se observaron efectos secundarios.

ConclusionesEl régimen de 16.000UI de calcifediol semanal durante 12 semanas, seguido de una dosis quincenal, es seguro y eficaz para las PVIH, aumentando significativamente los niveles de vitamina D y mejorando el cociente CD4:CD8 sin efectos adversos.

People with HIV (PWH) often have low levels of vitamin D.1–3 Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with less sunlight exposure, low weight, dietary changes, dark skin, malabsorption, obesity, chronic kidney failure, and in PWH it has been associated with the degree of disease progression, treatment with efavirenz, use of certain protease inhibitors, or treatment with zidovudine.4–7 The main function of vitamin D is the maintenance of bone integrity. Low levels have been associated with osteopenia and osteoporosis due to increased bone turnover, secondary hyperparathyroidism, and reduced bone mineralization. This leads to an increased risk of hip and spine fractures, loss of muscle performance, and increased risk of falls.8 Vitamin D deficiency has also been associated with insulin resistance and diabetes, dyslipidemia, neurocognitive alterations, cancer, worsening kidney function, autoimmune diseases, cardiovascular disease and, overall, an increase in mortality and morbidity, especially in PWH.9,10

Currently, a daily intake of 600–800IU/d is recommended for people over 50 years of age. According to the European HIV guidelines,11 deficiency is defined if vitamin D concentrations were below 10ng/mL, and insufficiency, if they were less than 20ng/mL. These same guidelines recommend determining vitamin D levels in people at risk of having low levels, especially if they have a higher risk of fracture. However, they do not indicate which regimen is best in patients with insufficiency, nor how long to maintain them. Nevertheless, now there are no clear guidelines on which vitamin D regimen and formulation should be used in these patients. In this sense, the main objective of our study was to compare the effectiveness of the three treatment regimens in terms of evaluating the proportion of PWH who do not achieve levels higher than 20ng/mL (considered as sufficiency). Differences in changes in levels of vitamin D, calcium, phosphorus, PTH, CD4:CD8 ratio, and bone mineral density were also evaluated.

Materials and methodsPatients and study designA prospective observational study was conducted at the Infectious Diseases Unit at Reina Sofia Hospital (Murcia, Spain), by analyzing 204 HIV-infected outpatients who were on stable ART whose vitamin D levels had been measured (fasting status). Patients were followed up in our department and visited between December 2017 and December 2020. The study was approved by the hospital ethical committee and all subjects provided written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were renal insufficiency (defined as glomerular rate filtration<60mL/min, estimated using Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation), hyperparathyroidism, hypercalcemia or hyperphosphatemia, hepatic insufficiency (defined as Child Pugh stage C), patients under chemotherapy, and those already receiving vitamin D, bisphosphonates, and calcium supplements (along with the other classical exclusion criteria).

The patients came to consultation on fasting status and underwent analysis and a guided interview using questionnaires.

Quantification of laboratory valuesTo determine 25 hydroxy vitamin D (25OHD) concentrations and PTH levels, automated immunoassays were used with ADVIA Centaur Vitamin D Total Inmunoassay (Siemens). Secondary laboratory variables included serum levels of calcium (8.5–10.5mg/dL), phosphate (2.5–4.8mg/dL), alkaline phosphatase (40–129IU/L), CD4 and CD8 lymphocytes counts, and HIV viral load (COBAS, AmpliPrep/TaqMan HIV-1 test, Roche Diagnostics).

Group 1 was supplemented with 16,000IU or 0.266mg of vitamin D3 calcifediol weekly for 12 weeks. Subsequently, they continued taking the same dose every 15 days until completing 48 weeks. Group 2 was supplemented with calcifediol 180,000UI or 3mg every 12 weeks; and Group 3 with calcifediol 180,000UI or 3mg every 4 weeks for 12 weeks. Subsequently, they continued with calcifediol 3mg every 12 weeks until completing 48 weeks.

During follow-up, all patients were reevaluated 3 times. Vitamin D toxicity was defined as concentrations above 150ng/mL.12

The change in plasma levels of 25OHD at 12, 24 and 48 weeks of treatment and the proportion of patients who did not exceed levels of 20ng/mL were analyzed.

The change in vitamin D levels from baseline at the three study points was assessed, and whether there were differences between the three treatment groups was determined.

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate whether there were statistically significant differences in the proportion of patients who did not reach the limit of 20ng/mL at 48 weeks. In addition, we evaluated whether there were differences in the change in 25OHD levels throughout the follow-up in each of the groups and between each of them.

On the other hand, we evaluated whether there were differences in the change in the analytical levels of PTH, Calcium, phosphorus and CD4:CD8 ratio in the same weeks of treatment. The change in BMD levels in spine and hip was also determined.

The safety and tolerance profile of the treatment used was analyzed.

Physical activity was evaluated through the iPAQ (International physical activity questionnaire) (https://sites.google.com/view/ipaq/score).

Statistical analysisThe baseline characteristics of our population are presented through a descriptive analysis of the different variables. Quantitative variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) unless indicated. Categorical variables are represented as frequency (n) and percentage (%).

To check whether there were significant changes in the determinations of some variables after the initiation of treatment with calcifediol, we used the T test for related samples if there were at least 2 determinations over time (BMD before and after the intervention) and the one-way ANOVA for repeated measures in the case of more than 2 determinations.

We used the mixed ANOVA for repeated measures to evaluate the impact of the different treatments on the change in levels of 25OHD, PTH, Calcium, Phosphorus and CD4:CD8 ratio. The non-existence of significant outliers and the assumptions of normality of variables, homogeneity of variances, homogeneity of covariances, and sphericity (Mauchly test) were checked. If these tests were significant, the Bonferroni correction was used for the analysis of multiple comparisons.

We consider statistical significance for p values less than 0.05.

Statistical calculations were performed using the statistical package IBM SPSS Statistics® version 24.0 for Windows® and the free software version 3.31 ‘R’ (The R Project for Statistical Computing).

ResultsScreening was performed on 204 patients, of whom 124 had levels lower than 20ng/mL, and 112 patients who met inclusion and non-exclusion criteria were included (8 were excluded due to lack of collaboration and 8 due to osteopenia/osteoporosis).

The baseline characteristics of patients are represented in Table 1. In summary, 112 patients were included, with a mean age of 51.6±10.5 years and 71.4% men. All received ART with a mean duration of 9.5±7.6 years. All patients received a regimen with NRTI in combination with NNRTI (44.6%), PI (25%), INSTI (39.3%). Regarding 25OHD levels, the average was 13.89±4.18ng/mL and PTH levels were 56.8±39.5pg/mL.

Distribution of baseline characteristics between the three treatment groups.

| Group 1(n=61) | Group 2(n=28) | Group 3(n=23) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)—M (SD) | 52.10 (10.69) | 52.79 (10.88) | 48.78 (9.66) | 0.348 |

| Sex man, n (%) | 41 (67.2) | 21 (75.0) | 18 (78.3) | 0.540 |

| Medical history—n (%) | ||||

| Mellitus diabetes | 2 (3.3) | 4 (14.3) | 1 (4.3) | 0.126 |

| Arterial hypertension | 12 (19.7) | 3 (10.7) | 1 (4.3) | 0.166 |

| Dyslipidemia | 17 (29.8) | 11 (39.3) | 7 (33.3) | 0.683 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1 (1.6) | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.220 |

| Cerebral vascular disease | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.656 |

| HCV coinfection—n (%) | 13 (21.3) | 8 (28.6) | 4 (17.4) | 0.610 |

| Toxic habits—n (%) | ||||

| Active smoking | 31 (50.8) | 15 (53.6) | 12 (52.2) | 0.970 |

| Alcohol consumption | 14 (23.0) | 2 (7.1) | 7 (30.4) | 0.096 |

| Consumption of drugs | 6 (10.3) | 3 (10.7) | 3 (13.0) | 0.939 |

| Physical activity level—n (%) | 0.530 | |||

| Low | 43 (70) | 18 (64) | 18 (78) | |

| Moderate activity | 9 (14.8) | 7 (25.0) | 2 (8.7) | |

| High activity | 9 (14.8) | 3 (10.7) | 3 (13.0) | |

| Origin Spain, n (%) | 46 (76.7) | 23 (82.1) | 16 (69.6) | 0.350 |

| HIV-related parameters—M (SD) | ||||

| CD4 nadir (cells/μL) | 328.26 (223.53) | 309.55 (252.98) | 378.94 (257.79) | 0.650 |

| CD4 (cells/μL) | 751.23 (351.18) | 800.48 (276.00) | 851.00 (604.43) | 0.600 |

| CD4:CD8 ratio | 0.87 (0.47) | 0.83 (0.40) | 0.82 (0.46) | 0.905 |

| Types of ART—n (%) | ||||

| NNRTIs | 26 (42.6) | 15 (53.6) | 9 (39.1) | 0.526 |

| PI | 15 (24.6) | 8 (28.6) | 5 (21.7) | 0.849 |

| INIST | 26 (42.6) | 8 (28.6) | 10 (43.5) | 0.406 |

| Anthropometric variables—M (SD) | ||||

| Waist (cm) | 90.57 (11.37) | 94.44 (12.44) | 88.57 (12.63) | 0.196 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.02 (4.48) | 26.86 (5.04) | 27.10 (4.95) | 0.869 |

| Blood pressure—M (SD) | ||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 128.57 (22.18) | 127.96 (16.99) | 118.27 (13.94) | 0.099 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 80.98 (11.53) | 82.04 (8.18) | 79.14 (11.06) | 0.633 |

| General analytical variables—M (SD) | ||||

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.36 (0.36) | 9.30 (0.35) | 9.45 (0.45) | 0.437 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 3.14 (0.62) | 3.31 (0.55) | 3.42 (0.66) | 0.288 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.83 (0.21) | 0.82 (0.14) | 0.81 (0.12) | 0.894 |

| GFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 96.25 (16.02) | 98.68 (13.15) | 96.94 (13.12) | 0.801 |

| 25 (OH) D at baseline (ng/mL) | 13.71 (4.36) | 14.63 (3.76) | 13.48 (4.25) | 0.549 |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 62.44 (49.41) | 47.14 (26.73) | 54.15 (18.08) | 0.365 |

| Bone densitometry—M (SD) | ||||

| Hip BMD (g/cm2) | 0.96 (0.38) | 0.90 (0.16) | 0.89 (0.14) | 0.569 |

| Hip T-score | 0.15 (1.52) | -0.15 (1.36) | -0.15 (1.06) | 0.578 |

| BMD L2L4 (g/cm2) | 1.05 (0.18) | 1.02 (0.18) | 1.04 (0.17) | 0.872 |

| T-score L2L4 | -0.13 (1.44) | -0.15 (1.45) | -0.04 (1.45) | 0.967 |

Group 1 represents doses of 0.266mg of calcifediol administered every week for 12 week followed every 2 weeks, whereas Group 2 represents doses of 3mg of calcifediol administered every 12 weeks, and Group 3 doses of 3mg every 4 weeks for 12 weeks followed by 3mg every 12 weeks. HCV: hepatitis C virus; ART: antiretroviral treatment; NRTIs: nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors; NNRTIs: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; PI: protease inhibitors; INSTI: integrase inhibitors; BMI: body mass index; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; GFR: glomerular filtration rate; PTH: parathyroid hormone; BMD: bone mineral density.

Fig. 1 represents the proportion of patients who maintain 25OHD levels below 20ng/mL. Significant differences are seen in all visits. In group 1, 3.4% (week 12), 3.4% (week 24) and 10.2% (week 48) had 25OHD levels below 20ng/mL, compared to group 2 who reached 46.4% (week 12), 24% (week 24) and 44% (week 48), and with group 3 they were 13% (week 12), 19% (week 24) and 31.6% (week 48). At week 48 there was a significant difference between group 1 and group 2 (difference −33.83%, 95% CI −54.76% to −12.9%; p<0001) and between group 1 and group 3 (difference −21.41%, 95% CI −43.69–0.87%; p=0.024). Between group 2 and 3 there were no statistically significant differences at 48 weeks (difference −12.42%, 95% CI −40.98% to 16.14%; p=0.402).

Grouped bar graph showing the proportion of patients with 25OHD levels lower than 20ng/mL distributed by treatment group. The standard dose (group 1) is shown in blue: calcifediol 0.266mg per week for 12 weeks and every 2 weeks thereafter. Group 2, represented in orange, received 3mg of calcifediol every 12 weeks. Group 3, shown in gray, received 3mg of calcifediol every 4 weeks for 12 weeks and then 3mg every 12 weeks.

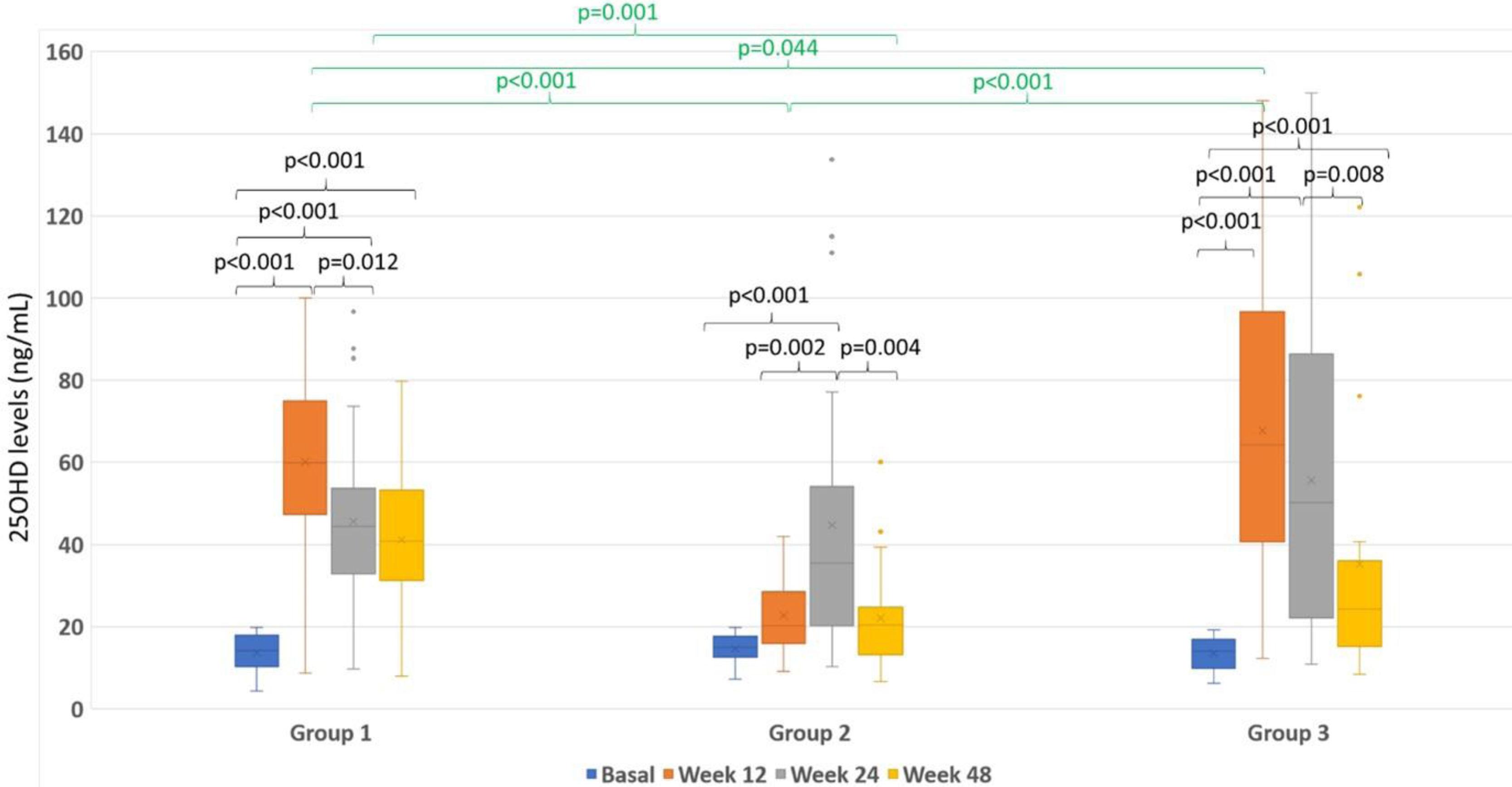

Fig. 2 represents the boxplot of the 3 treatment groups throughout follow-up and for each visit.

Box plots representing the magnitude of 25OHD levels (ng/mL) according to the group. The color of the boxes represents the week of treatment: blue (baseline visit), orange (week 12), gray (week 24) and yellow (week 48). The three treatment groups are represented on the X axis. The statistical significance is represented by groupings at the top.

In group 1 there was a significant increase in vitamin D levels from visit 0 to week 12 [13.7(0.55)ng/mL to 60.11 (2.31)ng/mL; p<0.001)], subsequently decreased in week 24 [45.61 (2.33); p<0.001)] to remain stable until week 48 [41.11 (2.05)ng/mL; p=0.902)]. The increase from visit 0 to week 48 was significant (p<0.001) and there was a significant decrease in levels between weeks 12 and 24 (p<0.001).

In group 2 there was a significant increase from visit 0 to week 24 [14.6(0.71)ng/mL to 44.74 (6.29)ng/mL; p<0.001)]. However, no significant differences were found between visit 0 and week 12 [22.7 (1.71)ng/mL; p=0.555)] nor week 48 [22.1 (2.27)ng/mL; p=0.365)]. There were differences between week 12 and 24 (p=0.002) and there was a significant decrease between week 24 and 48 (p=0.004).

In group 3 there was a significant increase from visit 0 to week 12 [13.48(0.88)ng/mL to 67.71 (7.6)ng/mL; p<0.001)], at week 24 [55.66 (8.11)ng/mL; p<0.001)], and at week 48 [35.24 (6.61)ng/mL; p<0.001)]. Between weeks 12 and 24 there were no differences in levels (p=0.265) and there was a significant decrease between weeks 24 and 48 (p=0.008).

As represented in the figure, when all groups were compared, we observed that there were no significant differences in the baseline visit. 25OHD levels were higher in group 3 compared to those in group 1 (p=0.044) and group 2 (p<0.001) at week 12. In turn, levels in group 1 were higher than those of group 2 (p<0.001). However, at week 24, no significant differences were found among the three groups. At 48 weeks, levels were significantly higher in group 1 compared to group 2 (p=0.001). No differences were found in the rest of comparisons.

Fig. 3 shows the box plots of changes in calcium, phosphorus, PTH, CD4:CD8 ratio and bone mineral density.

Box plots of the changes in levels of calcium, phosphorus, PTH, CD4:CD8 ratio and bone mineral density (BMD). (A) Shows changes in calcium levels; (B) shows changes in Phosphorus levels; (C) shows changes in PTH levels; (D) shows the CD4:CD8 ratio; (E) shows the changes in hip bone mineral density (BMD); (F) shows the changes in spine BMD; baseline is shown in blue color; week 12 is shown in orange color; week 24 is shown in gray color; week 48 is shown in yellow color.

When analyzing the changes in Calcium (Fig. 3A), Phosphorus and PTH levels (Fig. 3B), we observed a significant decrease in PTH levels (Fig. 3C) from the initial visit to week 12 (p=0.039) with no differences observed with respect to the rest of the visits or among the different regimens. No changes in calcium or phosphorus levels were observed among the different regimens or visits (data not shown).

Regarding the CD4:CD8 ratio (Fig. 3D), from baseline visit to week 48 we observed a significant increase in group 1 [0.87±0.06–0.96±0.06; p<0.001)]; in group 2 [0.83±0.076–0.94±0.086; p=0.005] and in group 3 [0.82±0.09–0.91±0.009; p=0.008)]. No differences were found in the increase among the three groups (p>0.05).

Considering the change in bone mineral density (Fig. 3E and F), there were no significant differences in the three groups. With group 1 there was a change between the baseline visit and week 48 from 0.96 (0.04) to 0.91 (0.02)g/cm2, in group 2 from 0.90 (0.03) to 0.83 (0.02)g/cm2, and group 3 from 0.89 (0.005) to 0.91 (0.005)g/cm2; p>0.05.

Concerning the security profile, all regimens were well tolerated, and no patients showed side effects during follow-up. There were 7 patients (28%) in group 3, 3 patients (12%) in group 2, and one patient (1.7%) in group 1 who presented 25OHD levels higher than 100ng/mL, and only one patient (4%) in group 3 had levels higher than 150ng/mL. No other alterations were observed.

DiscussionIn this observational study performed in PWH, we have observed that treatment with different formulations of calcifediol improves 25OHD levels. However, not all regimens have the same effect. With the treatment regimen with lower weekly doses during the first 12 weeks and subsequently every 2 weeks for a year, about 90% of patients reached concentrations higher than 20ng/mL, while with the rest of the high-dose regimens, only 53% of the total patients included and 62% of the patients who finished the study achieved it. Although no differences were found between the two high-dose regimens, regimen 3 achieved similar levels to regimen 1 at the end of follow-up. However, the proportion of patients who presented 25OHD concentrations lower than 20ng/mL were significantly higher in both group 2 and group 3 compared to group 1.

On the other hand, the results of this study demonstrate that vitamin D supplementation is well tolerated and safe with no side effects observed, despite using high doses of calcifediol and exceeding the toxicity threshold of 150ng/mL in only one patient. In the present study, as in others, supplementation did not significantly affect calcium or phosphorus levels. Instead, we detected a significant reduction in PTH levels but only at the beginning of treatment and no differences were observed in the different regimens.

To our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in PWH that attempts to compare low-dose regimens of vitamin D treatment with high-dose regimens.

To date, there are no proven recommendations for the indication, dose, or type of preparation for vitamin D supplementation in PWH. The European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS)11 recommends the administration of vitamin D supplements if levels are less than 10ng/mL, or are below 20ng/mL in case of osteoporosis, osteomalacia, or there is an increase in PTH. The objective is to maintain levels above 20ng/mL, which has been shown to be effective to correct bone metabolism,13 although other studies suggest that this should be above 30ng/mL.14

Currently, there are no studies that evaluate the frequency of determination of vitamin D levels in HIV patients taking ART. To date, studies have been carried out in HIV patients with different doses of D2 or D3 for supplementation and different dosing schedules, both daily and intermittent (monthly and quarterly) with discordant responses,15–18 although the use of vitamin D3 has shown a greater increase in serum 25OHD levels compared to D2 supplementation.19 Etminani-Esfahani et al.20 reported an improvement of +31ng/mL with a single dose of 300,000IU cholecalciferol, while Piso et al., using the same dose, found little improvement (+4ng/mL).18 Longenecker et al. with 4,000IU of cholecalciferol per day described an increase of +5ng/mL after 3 months of supplementation.17 In another study carried out in Spain with monthly supplementation with 16,000IU of calcifediol, they observed an increase of 16.4ng/mL of 25OHD and managed to reduce the proportion of patients with deficiency from 84 to 24% after 9 months. But still, there was a high level of patients with deficiency.21 These results were slightly better in the work of Elisabet Lerma Chippirraz et al.22 where 82.1% of patients with deficiency and 83.9% of patients with insufficiency reached levels>20ng/mL at 2 years of follow-up.

To our knowledge, our study is the longest conducted in which several calcifediol regimens are compared, including high-dose regimens. A dose of 16,000IU of calcidiol weekly is equivalent to 2285IU daily. Subsequently, with biweekly administration, they are equivalent to 1142IU daily. The dose of 180,000IU every 3 months was initially chosen because it would be equivalent to 2000IU daily, that is, like 16,000IU weekly. However, we also wanted to evaluate for once what the administration of higher doses would mean, that is, 180,000IU per month for 3 months, which would correspond to 6000IU per day. In our population, we chose the use of calcidiol because it has been shown to be 4–5 times more potent than D3 in increasing serum 25OHD,8,23 and it is the form of vitamin D with higher affinity for the specific globulins binding vitamin D.

Our surprise was that, despite giving them equivalent daily doses, the increase in 25OHD in group 2 was significantly lower than group 1 at 12 weeks (44.74±6.29 vs 60.11±2.31ng/mL), and only 53.6% of patients reached levels higher than 20ng/mL compared to 96.6% of patients in group 1. On the other hand, with group 3, despite giving them very high doses each month, levels were like those achieved in group 1 (67.71±7.6ng/mL) and 87% had levels higher than 20ng/mL at 12 weeks. Afterward, when the administration is spaced every 12 weeks, although no differences were seen between groups 1 and 2, proportion of patients with levels above 20ng/mL at 48 weeks was significantly higher in group 1 compared to groups 2 and 3, which showed the greater effectiveness of this regimen. On the other hand, although no side effects appeared throughout the study, 28% of patients of group 3 and 12% in group 2 had 25OHD levels above 100ng/mL, compared to only 1.7% of patients in group 1. The explanation for this difference is not clear. It is possible that a single administration of 3mg may not maintain stable levels of vitamin D for a long time. Instead, taking 0.266mg every 15 days could provide a more constant and regular release of vitamin D. Other possibility is that a higher dose of calcifediol could be metabolized and excreted more quickly than smaller doses administered more frequently. The results of studies in HIV patients with high-dose vitamin D have been carried out with cholecalciferol and confirm our results. Meanwhile, Giacomet V et al.,16 with supplementation of cholecalciferol 100,000IU every 3 months, found that 20% remained with deficient levels after 12 months of follow-up. On the other hand, Havens P et al.15 found that the administration of 50,000IU of cholecalciferol monthly was associated with a high proportion of patients with high levels of vitamin D. Eckard AR et al.24 found similar results with high doses (18,000IU, 60,000IU and 120,000IU) of cholecalciferol in HIV patients followed-up for 12 months, but administered monthly. These results strengthen the results of our study in the sense that high-dose regimens only achieve normal levels of vitamin D if they are administered every month. On the other hand, when they are administered every 3 months, a high proportion of patients remains with insufficiency or deficiency levels.

In addition to the improvement in vitamin D levels, we observed a significant reduction in PTH levels in all groups in the first weeks of treatment, and they remained stable throughout the follow-up. This could have a positive impact on bone turn-over25 and is similar to what was found in other studies.21,22 There is controversy regarding the impact that vitamin D supplementation can have on correcting PTH levels. In the study carried out by Lerma-Chippirraz et al.,22 they found that 67.2% of individuals with baseline hyperparathyroidism reached levels of <65pg/mL of PTH. In the study by Bañon S et al.,21 supplementation with 16,000IU of calcidiol achieved a reduction of 4.9pg/mL in PTH levels and the proportion of secondary hyperparathyroidism from 43 to 31% after a median follow-up of 9.3 months.

In our study, we did not find significant changes in BMD in either hip or spine, probably because the doses used were low, duration of treatment was insufficient, and because the number of patients in the study was small. The studies analyzed have observed disparate results and their heterogeneity makes it difficult to evaluate the impact that supplementation may have.26 In general population, a slight improvement in neck BMD26 has been observed, and in HIV patients the results have been similar to ours with little or no impact on BMD, although it has an impact on markers of bone turnover.15,27,28

Another interesting finding of our study was that in all treatment groups a significant increase in the CD4:CD8 ratio was observed without finding differences among the groups. Although a control group without vitamin D supplementation was not included for direct comparison, the beneficial effects of vitamin D on immune function are well-documented. Vitamin D is known to modulate immune responses, particularly in enhancing adaptive immunity and regulating inflammation, which may play a critical role in the management of immune recovery in HIV-infected patients.29,30 The CD4:CD8 ratio is widely regarded as a valuable marker of immune health, particularly in HIV patients. A higher ratio is generally associated with better immune function and lower immune activation, which are essential in reducing the risk of non-AIDS-related complications. Echard et al.24 observed that high doses of vitamin D decreased immune activation and exhaustion. Giacomet et al.16 detected that it reduced the Th17/Tregs ratio, and Dougherty et al.31 observed a minimal increase in CD4 T lymphocytes and a decrease in the activation profile of CD8 T lymphocytes in patients receiving ART. These findings underline vitamin D's potential to favorably influence the CD4:CD8 ratio by reducing immune exhaustion and enhancing immune recovery, thus supporting overall immune resilience in patients undergoing antiretroviral therapy.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, the study did not account for changes in other factors that could affect vitamin deficiency, such as diet and sunlight exposure duration. Nonetheless, consistent guidance was provided to all participants, and those who were not receiving supplements showed minimal change. Secondly, the research was carried out in a mainly urban Caucasian community, situated at a certain latitude with a set sunshine duration, which may not make the findings universally applicable. Nevertheless, the results might be relevant to other areas with comparable conditions. Third, there was a low number of patients, especially in the high-dose groups. However, although the ideal study would be to carry out a clinical trial, the results obtained encourage that the routine use of such high doses is not good practice.

ConclusionsThis is a long-term study in HIV patients showing that supplementation with a weekly dose of 16,000IU calcidiol for 12 week and after every 2 weeks for 48 weeks is safe and effective, significantly improving serum 25OHD levels and decreasing levels of PTH during follow-up. Likewise, high doses of calcifediol of 180,000IU administered monthly reach similar levels. However, high-doses calcifediol administration every 12 weeks failed to achieve optimal vitamin D levels after 48 weeks. Although administration every 4 weeks of high doses could achieve adequate vitamin D, it could exceed the toxicity threshold in the laboratory, which is why we advise against its administration.

Authors’ contributionVC and EB developed the study protocol. VC, CT, AM, CB, SV, EGV, JB, MM and EO have contributed to patient recruitment. AA, RR, MDH and MIM have collaborated in preparing and completing the database. MRV and NS in analytical determinations. EB and VC contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Everyone has contributed to the evaluation and correction of the manuscript.

Patient consent statementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patients. The study design was approved by the Comité de Ética de la Investigación of Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía in accordance with the ethical standards currently applied in the country of origin.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data availability statementData is available if required.

We would like to thank all patients for their participation in this study. Also thank the Reina Sofia hospital, the IMIB and the University of Murcia.