A public funded immunization program targeting influenza, COVID-19 and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), was introduced in Spain for the 2023/2024 season. Effective immunization strategies depend on product coverage and effectiveness.

ObjectivesEstimate of the impact of three severe acute respiratory infections (SARI) immunization strategies, during the 2023/2024 respiratory illness season in a Spanish health department.

MethodsWe conducted an ecological study to compare cumulative hospitalization rates of SARI between the 2022/2023 and 2023/2024 seasons. Subsequently, a cross-sectional study was conducted to describe immunization coverage. Three observational test-negative case–control studies were carried out to evaluate the vaccine effectiveness (VE) against influenza and COVID-19 and the effectiveness of immunization with nirsevimab.

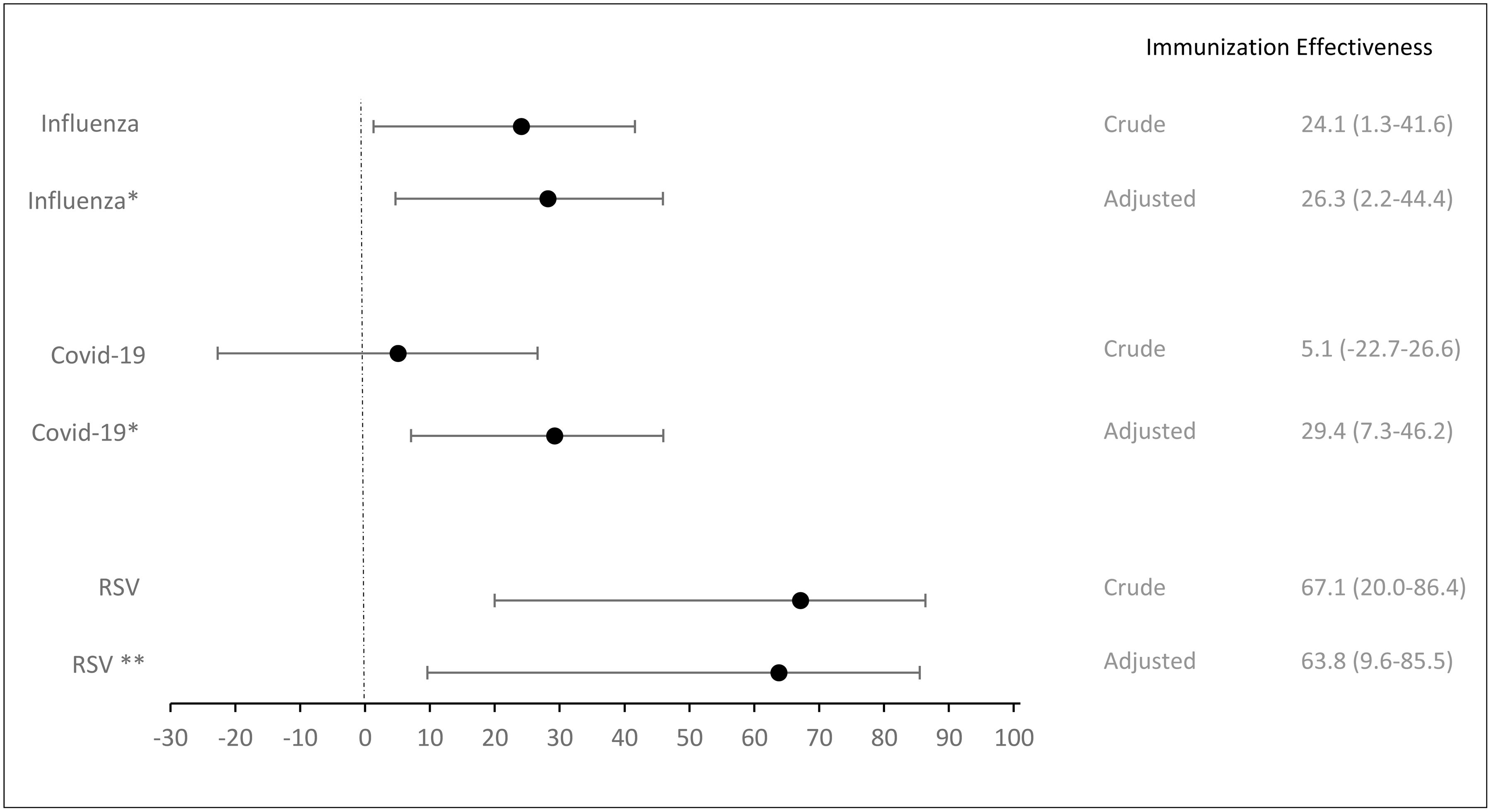

ResultsDuring the 2023/2024 season 2952 patients were hospitalized due to SARI, representing hospitalization rates of 322.6/100,000 inhabitants (RR=0.78), indicating a 21.8% (CI: 14.8–28.1) overall effectiveness of the immunization strategies (EIS) against SARI. The global EIS for influenza was 26.7% (CI: 15.2–36.7), with 5.9% (CI: −10.1–19.5) for influenza A and 94.0% (CI: 86.4–97.4) for influenza B. For COVID-19, the EIS was 19.3% (CI: 7.2–29.3). The EIS for RSV was 52.5% (CI: 35.4–65.0) in children <1 year-old. For the 2023/2024 season, influenza vaccination in those aged >64 decreased 7.9%, while COVID-19 vaccination fell by 40.6% in individuals >60 years. Nirsevimab reached high coverage of 94.78%. The aVE was 28.2% (CI: 4.7–45.9) for influenza and 29.2% (CI: 7.1–46.0) for COVID-19. The overall adjusted effectiveness of nirsevimab was 63.8% (CI: 9.6–85.5).

ConclusionThe observed EIS was likely due to RSV immunization in infants’ high coverage with good effectiveness and low influenza B circulation.

En España se ha introducido un programa de inmunización financiado públicamente en la temporada 2023/2024, dirigido a la prevención de la gripe, de la COVID-19 y del virus sincitial respiratorio (VRS). La efectividad de estas estrategias de inmunización depende tanto de la cobertura alcanzada como de los productos.

ObjetivosEstimar el impacto de tres estrategias de inmunización frente a infecciones respiratorias agudas graves (IRAG) durante la temporada de enfermedades respiratorias 2023/2024 en un departamento de salud español.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio ecológico comparando las tasas de hospitalización por IRAG entre las temporadas 2022/2023 y 2023/2024. Posteriormente se realizó un estudio transversal para describir la cobertura de inmunización. Se llevaron a cabo tres estudios observacionales del tipo casos y controles con prueba negativa para evaluar la efectividad de la vacuna (EV) contra la gripe y la COVID-19 y la efectividad de la inmunización con nirsevimab.

ResultadosDurante la temporada 2023/2024 un total de 2.952 pacientes fueron hospitalizados debido a IRAG, lo que representa una tasa de hospitalización de 322,6/100.000 habitantes (RR=0,78), indicando una efectividad global de las estrategias de inmunización (EEI) frente a IRAG del 21,8% (IC: 14,8-28,1). La EEI global para la gripe fue del 26,7% (IC: 15,2-36,7), con un 5,9% (IC: −10,1 a 19,5) para la gripeA y un 94,0% (IC: 86,4-97,4) para la gripeB. Para la COVID-19, la EEI fue del 19,3% (IC: 7,2-29,3). La EEI para el VRS fue del 52,5% (IC: 35,4-65,0) en niños <1año de edad. Para la temporada 2023/2024, la vacunación antigripal en personas >64años disminuyó un 7,9%, mientras que la vacunación con COVID-19 se redujo un 40,6% en individuos >60años. Nirsevimab alcanzó una cobertura alta, del 94,78%. La efectividad ajustada de la vacuna fue del 28,2% (IC: 4,7-45,9) para la gripe y del 29,2% (IC: 7,1-46,0) para la COVID-19. La efectividad global ajustada de nirsevimab fue del 63,8% (IC: 9,6-85,5).

ConclusionesLa EEI observada probablemente se debió a la inmunización frente al VRS en lactantes, caracterizada por una alta cobertura, buena efectividad y baja circulación de la gripeB.

Acute respiratory illnesses are the most prevalent cause of morbidity worldwide.1 Although most ill individuals do not need medical care, annual epidemics contribute to 3–5 million cases of severe illness and result in 290,000 to 650,000 related deaths. Lower respiratory infections, alongside Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) are the deadliest communicable diseases.2 The World Health Organization defines severe acute respiratory infections (SARI) as “Patients with acute respiratory infection who have history of fever, cough and onset within the last 10 days (symptoms within 10 days) and require hospitalization.”3

Seasonal influenza alone accounts for approximately one billion cases annually globally,4 with many severe cases potentially preventable through vaccination. However, the effectiveness of vaccines varies due to circulating strains and the degree of similarity with available vaccines, and intrinsic patient factors.5,6

COVID-19, since 2020, has caused over 700 million cases and 7 million deaths globally, including over 13 million cases and 121,000 deaths in Spain.7 Although not strictly seasonal, the evolution of the variants and the pattern of circulation in waves remains concerning, particularly in periods of high demand of healthcare services, such as during respiratory illness seasons.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading cause of acute lower respiratory infections, accounting for 33 million cases worldwide in 2019. Leading to 3.6 million hospitalizations and over 100,000 attributable deaths occurring in children under five.8 During the 2022–2023 season in Spain, an estimated 32,787 RSV hospitalizations occurred, 37.9% (12,422) in children under 1.9 The BARI study estimated a cost of 3.8 million euros during the season 2017/2018 in two Spanish regions, primarily due to RSV hospitalizations in healthy children under one year old.10

Influenza, COVID-19 and RSV are not the only causes of SARI, but they share a significant impact on public health and are preventable through existing effective public health immunization strategies.11,12 In September 2023, governing bodies released immunization recommendations for the upcoming season.12 A public funded immunization program targeting all three viruses, was introduced in Spain. Including an updated SARS-CoV2 Monovalent vaccine for the Omicron XBB.1.5 lineage, four tetravalent influenza vaccines and RSV immunization for infants with nirsevimab, a long action monoclonal antibody.9 The RSV campaign, started in October for children born from April 1, 2023 to March 31, 2024 during their first RSV season.9 Meanwhile, COVID-19 and influenza vaccinations focused primarily on older adults, people with chronic conditions, healthcare professionals and other at-risk groups. Additionally, as new occurrence influenza vaccines were available for healthy children from 6 to 59 months.

Consistently evaluating public health strategies is pivotal for understanding their impact and guiding future interventions. Effective immunization depends on circulating strains and patient factors, while effective campaigns rely on coverage and product effectiveness. We aim to provide an integrated estimate of the impact of three SARI immunization strategies, at the end of the 2023/2024 respiratory illness season in one health department in Spain by: estimating the effectiveness of the SARI immunization strategies; describing immunization coverages and estimating the effectiveness of three immunization products used during the season (influenza vaccine, COVID-19 vaccine and nirsevimab).

MethodsThis retrospective study evaluated the effectiveness of immunization programs against severe acute respiratory infections (SARI) in patients admitted to Dr. Balmis General University Hospital. A tertiary hospital in a Spanish health department (HD), which served a population of 293,859 people, from week 40 of 2023 to week 20 of 2024. The study was approved by the Drug Research Ethics Committee of the Health Department of the General University Hospital of Alicante with code I2024-106 and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were respected. It is divided into three endpoints, each with its own study design, inclusion/exclusion criteria, variable selection and statistical analysis. Data regarding vaccination and immunization status was obtained from the Nominal Vaccination Registry of the Valencian Health Department (RNV). The rest of the clinical-epidemiological variables collected were obtained from the computerized clinical history.

For the first endpoint, an ecological study was conducted to compare the cumulative hospitalization rates of SARI between the 2022/2023 and 2023/2024 seasons. Were included patients admitted to the hospital that presented clinical symptoms compatible with SARI and underwent in-hospital diagnostic testing for infection either by rapid antigen test (SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza A+B Antigen Combo Rapid Test, Hangzhou Alltest Biotech CO. LTD) or real-time reverse transcription-polymerase (RT-PCR) for SARS-CoV-2, influenza A and B; and RT-PCR for RSV in nasopharyngeal or anterior nasal swab. The reference population used is the population assigned to the HD in November 2023 for the 2023–2024 season and in November 2022 for the 2022–2023 season. The frequency measure used is the rate per 100,000 population (T*105) of the overall SARI and the specific T*105 for: COVID-19, RSV, influenza A and influenza B. To calculate the magnitude of the association between the seasons and the incidence rate per 100,000 population, the relative risk (RR) was calculated with its 95% confidence intervals (CI), using the rate for the 2022–2023 season as a reference category. The effectiveness of the prevention programs in the 2023–2024 season was then calculated using the formula Effectiveness=(1−RR)×100.

Subsequently for the second endpoint, a cross-sectional study was conducted to describe vaccination coverage (VC) against influenza and COVID-19. VC was analyzed by percentage and a percentage variation between the seasons was calculated. Were included as vaccinated cases all people vaccinated in the present campaign, and in the case of COVID-19, with the available updated XBB vaccine.

Finally, for the third endpoint, three observational test-negative case–control studies were carried out to evaluate the vaccine effectiveness (VE) against influenza and against COVID-19 and the effectiveness of immunization with nirsevimab. The inclusion criteria were the same as for the first endpoint. For patients with multiple hospitalizations, only the first was considered. Patients younger than 6 months were excluded from the first two analyses and older than one for the nirsevimab analysis, as they were not eligible to receive immunization based on the recommendations. For COVID-19 and influenza analyses, inclusion was regardless of vaccination recommendations. From this total, a different selection algorithm was followed depending on the evaluation performed (Fig. 1). For the influenza and COVID-19 studies was collected the immunization status, sex, age, comorbidities and the Charlson Comorbidity Index was calculated, while for the RSV study also the week of admission, birth weight and presence of risk factors (prematurity, congenital heart disease, congenital lung disease, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, Down Syndrome, oncohaematological disease and immunodeficiency). For the effectiveness analyses, influenza cases were positive only for influenza, COVID-19 cases were those positive only for COVID-19. RSV cases were only positive for RSV. In all analyses, all patients who were negative in the diagnostic test for the three respiratory viruses were considered controls. Any patient who received the influenza or COVID-19 vaccine at least 14 days before presenting compatible symptoms was considered vaccinated. Patients who had received a dose of nirsevimab at least 7 days before the onset of symptoms were considered immunized. Patient recruitment was carried out within the Acute Respiratory Infections Surveillance System (SiVIRA). The same systematic approach was used for statistical analysis. First, a descriptive study of all patients included according to immunization status was performed and differences between them were compared using the Chi-square test. Then, to study the association between infection and the different possible associated factors in each of the substudies, the crude odds ratio (cOR) and the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) were calculated by logistic regression. Finally, the crude (cVE) and adjusted vaccine effectiveness (aVE) or immunization effectiveness for preventing infection and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated with the following formula: VE=(1−odds ratio)×100.

Case–control selection plot for analysis of influenza vaccine and COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness and nirsevimab effectiveness against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). I+: RT-PCR positive for influenza; I−: RT-PCR negative for influenza; C+: RT-PCR positive for COVID-19; C−: RT-PCR negative for COVID-19; R+: RT-PCR positive for RSV; R−: RT-PCR negative for RSV. *Only patients eligible to receive immunisation with nirsevimab. SARI: severe acute respiratory infection.

In all hypothesis contrasts, the level of statistical significance used was p<0.05. The analysis was performed using the IBM® SPSS® Statistics v.25.0 statistical software.

ResultsEffectiveness of the severe acute respiratory infections (SARI) immunization strategiesDuring the 2023/2024 season 2952 patients were hospitalized due to SARI. The cumulative hospitalization rates for SARI were 322.6 per 100,000 inhabitants in the 2023/2024 season and 412.3 per 100,000 inhabitants in the 2022/2023 season. Representing a relative risk (RR) of 0.78 for SARI hospitalization in the current season, indicating a 21.8% (CI: 14.8–28.1) overall effectiveness of the immunization strategies (EIS) against SARI in our HD. The global EIS for influenza was 26.7% (CI: 15.2–36.7), with 5.9% (CI: −10.1–19.5) for influenza A and 94.0% (CI: 86.4–97.4) for influenza B. For COVID-19, the EIS was 19.3% (CI: 7.2–29.3). The global EIS for RSV was 18.7% (CI: 3.4–31.5), but rose to 52.5% (CI: 35.4–65.0) in children under one year old (Table 1).

Hospitalization rate per 100,000 inhabitants for severe acute respiratory infection and immunization strategies effectiveness.

| Season 2023–2024 (W40–20)Hospitalization rate*105 (n) | Season 2022–2023 (W40–20)Hospitalization rate*105 (n) | RR (95% CI) | Effectiveness (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference population | 293,859 | 289,340 | ||

| ≤1 year old | 4,196 | 4,192 | ||

| >1 year old | 289,663 | 285,148 | ||

| Total | 322.6 (948) | 412.3 (1193) | 0.78 (0.72–0.85) | 21.8 (14.8–28.1) |

| Influenza | 105.8 (311) | 144.5 (418) | 0.73 (0.63–0.85) | 26.7 (15.2–36.7) |

| Influenza A | 103.8 (305) | 110.3 (319) | 0.94 (0.81–1.10) | 5.9 (−10.1–19.5) |

| Influenza B | 2.0 (6) | 34.2 (99) | 0.06 (0.03–0.14) | 94.0 (86.4–97.4) |

| COVID-19 | 136.1 (400) | 168.7 (488) | 0.81 (0.71–0.92) | 19.3 (7.9–29.3) |

| RSV | 80.7 (237) | 99.2 (287) | 0.81 (0.69–0.97) | 18.7 (3.4–31.5) |

| ≤1 year old | 1406.1 (59) | 2958.0 (124) | 0.48 (0.35–0.65) | 52.5 (35.4–65.0) |

| >1 year old | 61.5 (178) | 56.8 (162) | 1.08 (0.87–1.34) | – |

2023/2024 (W40–20): week 40 of 2023 to week 20 of 2024; 2022/2023 (W40–20): week 40 of 2022 to week 20 of 2023; RSV: respiratory syncytial virus; RR: relative risk; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

Boldface indicates statistical significance (confidence interval excludes 1).

For the population aged 64 and older, the influenza VC decreased 7.9% from the 2022/2023 season, to 2023/2024 season. Among healthcare personnel the VC also declined. Regarding COVID-19 vaccination, the 2023/2024 season also saw a 40.6% VC decrease in the population aged 60 and older and 34.4% among healthcare personnel. Nirsevimab reached a high coverage of 94.78% (Appendix Table 1).

Immunization effectivenessAmong the 2447 patients with SARI included in the influenza evaluation 1065 were vaccinated. 53.6% were male, 62.6% were aged over 65 years and 77% had at least one comorbidity. Influenza vaccination was associated with a 26% reduced likelihood of developing the disease (aOR:0.74; CI: 0.56–0.99) (Table 2). The overall aVE for influenza was 26.3% (CI: 2.2; 44.4) (Fig. 2). We estimated a 38.8% aVe (CI: 15.0–55.8) for individuals aged 65 and older. Additionally, in individuals with comorbidities, the aVE was a 38.5% (CI: 15.4–55.2).

Factors associated with the development of influenza (n=2447). Adjusted effectiveness of immunization against influenza.

| Influenza (n=266)n (%) | No influenza (n=2181)n (%) | Crude OR(95% CI) | Adjusted OR*(95% CI) | Adjusted OR**(95% CI) | Adjusted effectiveness***(95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccination | ||||||

| Yes | 100 (37.6) | 965 (44.2) | 0.76 (0.58–0.99) | 0.73 (0.55–0.97) | 0.74 (0.56–0.99) | 26.3 (2.2–44.4) |

| No | 166 (62.4) | 1216 (55.8) | 1 | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 133 (50.0) | 1179 (54.1) | 0.85 (0.66–1.10) | – | – | |

| Female | 133 (50.0) | 1002 (45.9) | 1 | |||

| Age | ||||||

| <65 years old | 101 (38.0) | 815 (37.4) | 1.03 (0.79–1.33) | 0.87 (0.65–1.16) | 0.83 (0.54–1.3) | |

| ≥65 years old | 165 (62.0) | 1366 (62.6) | 1 | |||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 16 (6.0) | 146 (6.7) | 0.89 (0.52–1.52) | – | – | |

| Asthma | 9 (3.4) | 32 (1.5) | 2.35 (1.11–4.98) | 2.48 (1.16–5.31) | – | |

| COPD | 5 (1.9) | 104 (4.8) | 0.38 (0.16–0.95) | 0.42 (0.17–1.05) | – | |

| Diabetes | 11 (4.1) | 137 (6.3) | 0.64 (0.34–1.21) | – | – | |

| Obesity | 7 (2.6) | 45 (2.1) | 1.28 (0.57–2.87) | – | – | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5 (1.9) | 100 (4.6) | 0.40 (0.16–0.99) | 0.41 (0.16–1.02) | – | |

| Hypertension | 23 (8.6) | 209 (9.6) | 0.89 (0.57–1.40) | – | – | |

| Liver disease | 0 (0.0) | 22 (1.0) | – | – | – | |

| Cancer | 10 (3.8) | 121 (5.5) | 0.67 (0.34–1.28) | 0.67 (0.35–1.30) | – | |

| Haematopathies | 2 (0.8) | 8 (0.4) | 2.06 (0.44–9.74) | – | – | |

| Down Syndrome | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | – | – | – | |

| HIV | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.3) | – | – | – | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ||||||

| ≥3 | 151 (56.8) | 1281 (58.7) | 0.92 (0.71–1.19) | 0.88 (0.59–1.33) | ||

| <3 | 115 (43.2) | 900 (41.3) | ||||

Out of the 2450 patients with SARI included for the COVID-19 evaluation, 1057 were vaccinated, 54.1% were male, and 64.4% were aged over 65 years. Among the vaccinated individuals, 84.4% were over 65 years old, compared to 49.2% of the unvaccinated group (Appendix Table 3). COVID-19 vaccination was independently associated with a 27% reduction in the likelihood of developing COVID-19 (aOR:0.73; CI: 0.55–0.96) (Table 3). The overall aVE of the COVID-19 vaccine was 29.4% (CI: 7.3–46.2) (Table 3). Similar to the influenza vaccine, the COVID-19 vaccine did not show effectiveness in people under 65 years (aVE: −09; CI: −99.6–49.0). However, it was more effective in those aged 65 and older, with an aVE of 33.1% (CI: 10.5–50.0).

Factors associated with the development of COVID-19 (n=2450).

| COVID-19 (n=269)n (%) | No COVID-19 (n=2181)n (%) | Crude OR(95% CI) | Adjusted OR*(95% CI) | Adjusted OR**(95% CI) | Adjusted effectiveness ***(95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccination | ||||||

| Yes | 113 (42.0) | 944 (43.3) | 0.95 (0.73–1.23) | 0.73 (0.55–0.96) | 0.71 (0.54–0.93) | 29.4 (7.3–46.2) |

| No | 156 (58.0) | 1237 (56.7) | 1 | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 146 (54.3) | 1179 (54.1) | 1.01 (0.78–1.30) | – | – | |

| Female | 123 (45.7) | 1002 (45.9) | 1 | |||

| Age | ||||||

| <65 years old | 57 (21.2) | 815 (37.4) | 0.45 (0.33–0.61) | 0.41 (0.29–0.57) | 0.52 (0.33–0.83) | |

| ≥65 years old | 212 (78.8) | 1366 (62.6) | 1 | |||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 22 (8.2) | 146 (6.7) | 1.24 (0.78–1.98) | 0.74 (0.44–1.25) | – | |

| Asthma | 3 (1.1) | 32 (1.5) | 0.76 (0.23–2.49) | – | – | |

| COPD | 15 (5.6) | 104 (4.8) | 1.18 (0.68–2.06) | 0.95 (0.53–1.70) | – | |

| Diabetes | 30 (11.2) | 137 (6.3) | 1.87 (1.23–2.84) | 1.41 (0.87–2.28) | – | |

| Obesity | 8 (3.0) | 45 (2.1) | 1.46 (0.68–3.12) | 1.41 (0.62–3.22) | – | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 26 (9.7) | 100 (406) | 2.23 (1.42–3.50) | 1.79 (1.09–2.93) | – | |

| Hypertension | 39 (14.5) | 209 (9.6) | 1.60 (1.11–2.31) | 1.15 (0.74–1.78) | – | |

| Liver disease | 0 (0.0) | 22 (1.0) | – | – | – | |

| Cancer | 26 (9.7) | 121 (5.5) | 1.82 (1.17–2.84) | 1.33 (0.79–2.26) | – | |

| Haematopathies | 7 (2.6) | 8 (0.4) | 7.26 (2.61–20.2) | 6.75 (2.11–21.6) | – | |

| Down Syndrome | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | – | – | – | |

| HIV | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.3) | – | – | – | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ||||||

| ≥3 | 200 (74.3) | 1281 (58.7) | 2.04 (1.53–2.71) | 1.34 (0.90–2.17) | ||

| <3 | 69 (25.7) | 900 (41.3) | ||||

Among the 134 infants eligible for immunization included in the study, 101 received the immunization against RSV. Of these infants, 53% were male, and 59.7% were under 2 months of age at the time of admission (Appendix Table 4). Of infants with SARI, 80.2% of RSV-negative cases received nirsevimab, compared to 57.1% of RSV-positive cases (Table 4).

Factors associated with RSV infection (n=134).

| RSV positive (n=28)n (%) | RSV negative (n=106)n (%) | Crude OR(95% CI) | Adjusted OR*(95% CI) | Adjusted effectiveness**(95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nirsevimab | |||||

| Yes | 16 (57.1) | 85 (80.2) | 0.33 (0.14–0.80) | 0.36 (0.15–0.90) | 63.8 (9.6–85.5) |

| No | 12 (42.9) | 21 (19.8) | 1 | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 16 (57.1) | 55 (51.9) | 1.24 (0.53–2.86) | – | |

| Female | 12 (42.9) | 51 (48.1) | 1 | ||

| Age (months) | |||||

| 0–2 months | 16 (57.1) | 64 (60.4) | 0.88 (0.38–2.03) | – | |

| >2 months | 12 (42.9) | 42 (39.6) | 1 | ||

| Week of admission | |||||

| W40–W4 | 23 (82.1) | 57 (53.8) | 3.95 (1.40–11.2) | 3.67 (1.28–10.5) | |

| W5–W20 | 5 (17.9) | 49 (46.2) | 1 | ||

| Birth weight | |||||

| ≤2500g | 5 (17.9) | 30 (28.3) | 0.55 (0.19–1.58) | – | |

| >2500g | 23 (82.1) | 76 (71.7) | 1 | ||

| Presence of risk factors | |||||

| No risk factors | 19 (67.9) | 74 (69.8) | 0.91 (0.37–2.23) | – | |

| At least 1 risk factor | 9 (32.1) | 32 (30.2) | 1 | ||

Infants immunized with nirsevimab were significantly 64% less likely to develop a lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI) due to RSV (ORa: 0.36; CI: 0.15–0.90). The overall adjusted effectiveness of nirsevimab was 63.8% (CI: 9.6–85.5) (Table 4).

DiscussionThis study evaluated the impact of immunization strategies on reducing hospitalizations due to SARI, overall effectiveness in reducing hospitalizations was modest and likely could be explained by the suboptimal VC and moderate VE (influenza and COVID-19), alongside low influenza B circulation and high nirsevimab coverage and effectiveness. We assessed two key aspects for determining the effectiveness of immunization strategies: vaccination coverage (VC) and vaccine effectiveness (VE). The basic reproductive number (R0), refers to the average number of secondary infections from one primary case in a susceptible population. High-efficacy vaccines (80–85%) are impacted by VC, particularly for pathogens with short-lived or variable immunity.13 Therefore, a combination of effective immunization and high coverage is essential to reduce virus transmission and, consequently, morbidity and mortality. While there is no universal consensus on the exact percentage of population immunity needed to reduce virus transmission, achieving high immunization coverage is known to disrupt viral transmission cycles.13 In our campaign, the target VC for COVID-19 and influenza was 75% for individuals over 60 and healthcare workers, 60% for those at risk of SARI, and 98% coverage for monoclonal antibodies against RSV in children under 1 year.9 The strategies achieved a 21.8% effectiveness in reducing hospitalization rates compared to the 2022/2023 season.

During the 2023/2024 season, the influenza vaccination program was expanded. For the first time, all children under 5 were eligible for vaccination and a tetravalent intranasal vaccine was introduced. The eligibility age for vaccination was also lowered from 65 to 60 years, and smokers of any age were included. Despite these efforts, VC did not improve, in fact, the VC for individuals over 64 years, in our HD was below the national average of 65.97%,14 well below the recommended coverage of 75%. Notwithstanding the number of vaccinated individuals at higher risk of a severe infection (chronic patients) increased 21.6%. Healthcare personnel, a priority group due to their close contact with at-risk populations, also experienced one of the lowest VC recorded in our HD. The overall VE of vaccines administered during this season was low to moderate (aVE of 28.2%). Earlier estimates had indicated a higher VE of 63% against influenza A (H1N1)pdmo9.15 VE published estimates are limited and variable, ranging from 41.4% to 61%.16,17 The effectiveness observed was also lower than the 40.6% observed in our HD during the previous season.18 This season low VE and VC likely impacted the overall effectiveness of the vaccination program. The global EIS for influenza was 26.7%, and when broken down by strain, the EIS was much lower for influenza A compared to influenza B. The high effectiveness against influenza B can likely be attributed its limited circulation. Most influenza cases this season were caused by H1 (pdm09), followed by H3. Influenza A has low R0 values, hence transmission rates would be managed with a vaccine of moderate effectiveness combined with moderate VC.13

Given the overlapping target populations, the COVID-19 and influenza vaccination campaigns were conducted jointly. By the end of 2021, more than 89% of the Spanish population was fully vaccinated against COVID-19.19 However, VC sharply declined afterward. We observed a 40.6% reduction in vaccination, among individuals over 60, this trend is seen in other countries. Across the EU/EEA, the median VC in individuals over 60 was 12.0%, with significant variability between countries.20 The XBB.1.5 lineage, dominant in Spain in September 2023, was later replaced by the BA.2.86 strain, which accounted for 60.47% of cases of SARI.21 Given the emergence of new variants and the waning immunity, maintaining high VC among at-risk groups should remain a priority. In this study, 64.4% of hospitalized patients were over 65 years old, and 75.1% had comorbidities, making them eligible for vaccination. The updated monovalent COVID-19 vaccine provided protection against hospitalization (aVE: 29.2%), which slightly increased among those aged 65 and older. These figures were lower than those observed in earlier stages of the vaccination campaign. A community-based study estimated a 54% VE against symptomatic infection at a median of 52 days post-vaccination, with pronounced VE decline over time. The vaccine was effective against both JN.1 and XBB-related lineages.22 An aVE estimate up to December showed a 62% effectiveness against COVID-19 hospitalizations.23 Another mid-season study reported a VE of 47% for the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron XBB.1.5 variant.17

Omicron variants challenge immunization efforts due to high transmissibility, short incubation, immune escape, and waning immunity. A study estimated that to create herd immunity against emerging variants, the effectiveness of adapted vaccines against omicron BA1 and BA4-5 in preventing infection must be exceed 80% and the VC must be higher than 70%.24

Among the immunization strategies employed during the 2023/2024 season, those targeting RSV had the most notable impact. Previously, the only immunization option available in Spain was palivizumab, a MA licensed for children at high risk of hospitalization due to LRTI. Although an RSV vaccine for pregnant women was approved in July 2023, it was still unavailable during this season.25 Two hundred seventy-seven thousand doses of nirsevimab were administered during the season in Spain, achieving a mean coverage of 92% in children born during the season and 88% in those born before the campaign's start. The strategy involved administering the immunization in maternity wards for infants born after the campaign's start on October 1, with a target coverage similar to the coverage achieved during the hepatitis B systematic vaccination in maternity wards until 2017.9 In our HD nirsevimab was widely accepted, with a 94% coverage. When comparing the last two seasons, we estimated an overall modest effectiveness of 18.7% for the RSV immunization strategy, with notably higher effectiveness in children under one year of age. This result was expected, since there were no specific strategies in place for other age groups, except for the small group of children under two years old with severe risk factors for RSV LTRI. The 64% reduction in odds of RSV infection with nirsevimab was consistent with earlier studies, while to our knowledge; few studies have described the outcomes of an entire season post-nirsevimab approval, as few countries have included it in their immunization schedules. Clinical trials demonstrated a 70.1% reduction in the incidence of medically attended RSV LRTI and a 62.1% efficacy against hospitalization.26 A study in Navarra estimated that nirsevimab prevented 60.2 hospitalizations per 1000 infants by December, the immunization strategy preventing 47.6% of RSV hospitalizations.27 Similarly, an interim analysis in Galicia reported an effectiveness of 82% preventing RSV related LRTI hospitalizations.28 Early estimates in first three months of the season describe a nirsevimab RSV effectiveness of 70.2%.29 and a reduction in hospitalization for infants between 74% and 75%,30 by the end of the season in our study we found a more modest effectiveness of 63.8%.

Key limitations include ecological studies inherent limitations, as population-level associations may not be generalizable to individuals and overlook effective non-pharmaceutical preventive measures. However, they provide valuable simple insight into the overall impact of immunization strategies. Our estimates are limited to one HD and may not represent other populations. The evaluation period (weeks 40–20) aligns with peak respiratory infection season, but COVID-19 cases continued to rise beyond this period, potentially leading to an overestimation of COVID-19 VE. We were unable to genotype COVID-19 variants among patients, relying instead on population-level data. In the 2022/2023 season, higher RSV circulation likely increased natural immunity in both vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals, yet we still observed differences, suggesting an additional impact from nirsevimab, highlighting the need for continued evaluation in future seasons with different RSV circulation patterns. RSV immunization coverage data in our HD was only available up to January 2024, but we expect minimal variation beyond that. Additionally, the small number of RSV cases, limited our ability to perform more stratified analyses, especially on high-risk children.

ConclusionThe modest EIS was mainly due to RSV immunization in infants and low influenza B circulation. Continuous evaluation of respiratory illnesses seasons is essential, especially for understanding the impact on at-risk populations. The success of future campaigns will depend on both the effectiveness of vaccines and immunizations and the coverage achieved within target groups. Ongoing efforts to improve vaccine acceptability – especially for COVID-19 and influenza – and expanding RSV immunization to broader groups, will be crucial for enhancing the effectiveness of future strategies.

FundingThis research was supported by Alicante Institute for Health and Biomedical Research (ISABIAL). The funder had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the manuscript (project number: 2024-0288).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare not to have any conflicts of interest that may be considered to influence directly or indirectly the content of the manuscript.