Proton pump inhibitors (PPI) and histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RA) are frequently used in critically ill patients for prevention gastrointestinal hemorrhage.1 However, they can lead to bacterial overgrowth with an increased risk of Clostridioides difficile associated disease (CDAD). Association between PPI and the risk of C. difficile-associated diarrhea has been supported by several studies.2,3 There are few data about the incidence of CDAD in critically ill children4 and the relationship with gastric acid suppression.

We conducted a retrospective, observational, study including critically ill child with CDAD or C. difficile carriage (CDC) during 6 years. CDAD was defined as the presence of abdominal distension, abdominal pain and/or liquid stools associated with signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome and/or a rise in the acute phase reactants. CDC was defined as the isolation of the bacillus in the absence of signs of infection. Toxigenic C. difficile was isolated by stool culture. Cytotoxicity assay was performed in human fibroblast (MRC-5) cell culture and the isolated strains of C. difficile (CD) were then retested for toxin production. The strains were typed by ribotyping assay.

2526 patients were admitted to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (70% of them were cardiac patients). 1655 took ranitidine, 356 PPI, 178 both drugs and 337 did not receive any treatment.

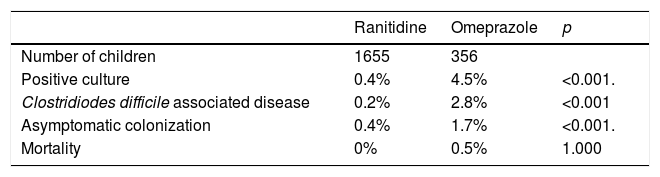

Twenty-two patients (1.1%) had a positive culture for CD. The mean age was 1.5±1.9 years and 54.5% were males. 13 children were diagnosed as CDAD (incidence of infection of 0.6%) and 9 as asymptomatic carriages. All of them were cardiac patients and received broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. The incidence of a positive culture was 4.5% with PPI group and 0.4% with ranitidine (p<0.001). The incidence of both CDAD and asymptomatic colonization was significantly higher in patients taking PPI (2.8% and 1.7% respectively) than with H2RAs (0.2% and 0.4% respectively), p<0.001. (Table 1). Only one child had recurrent CD and was on PPI therapy for a long time. Two patients died, both of which were in the PPI group.

Colonization of the feces occurs in 16–35% of hospitalized patients, increasing proportionally in relation to the length of hospital stay and, in particular, after antibiotic therapy. Patients can be asymptomatic or present with fulminant colitis. The most common presentation is diarrhea, fever, colicky abdominal pain, and leukocytosis in a patient treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Although CDAD is relatively rare in children, mainly before 12–24 months of age, its incidence among hospitalized children is increasing,5,6 especially in those with oncological, postsurgical or critical illness.4

Some studies show an association between CD and PPI,7 but few have analyzed the association between CD and acid suppressant drugs in children8,9 and in critically ill adult patients.10 Our study is the first that analyzed the association between these two factors in critically ill children concluding that PPI may increase the incidence of CD more than H2RAs. It is important, to distinguish between true disease and asymptomatic carriages due to the high prevalence of fecal colonization in children.

Several factors may be involved in this association. PPI induce a more potent gastric acid suppression that may alter the intestinal microbiota and stimulate the growth of CD. It also induces a delay in gastric emptying which can predispose to bacterial overgrowth. Moreover, the presence of bile salts in gastric contents may contribute to spore germination in the stomach. Second, in PPI inhibit neutrophil bactericidal activity, chemotaxis and phagocytosis and may favor CD infection.

Our study is a retrospective study and there are other factors that can predispose to CD infection which have not been analyzed, such as immunological status or the concomitant use of other drugs that are associated with this infection.

In conclusion, the use of PPI in critically ill children may increase not only the asymptomatic carriages but also the risk of CDAD which can worsen the prognosis of these patients. For this reason, the use of gastric acid suppressant therapy, especially PPI, should be bounded to patients with a high risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. On the other hand, although CD carriage rates are high in the pediatric population, critically ill children are exposed to several factors that make it necessary to provide an adequate epidemiological surveillance.

FundingMother-Child Health and Development Network (Red SAMID) of Carlos III Health Institute, RETICS funded by the PN I+D+I 200-2011 (Spain), ISCIII-Sub-Directorate General for Research Assessment and Promotion and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), network ref. RD16/0026/0007.

To the Gregorio Marañón Pharmacy Service for the help for develop this study.