We investigate bronchopulmonary colonization patterns in Spanish people with CF (pwCF), gathering clinical, demographic, and microbiological data to supplement nine years of registry information, comparing 2021 findings with a similar multicenter study conducted in 2013.

MethodsSixteen CF units from 14 hospitals across Spain participated, each randomly recruiting around 20 patients. Patients provided sputum samples for culture. The clinical, demographical, microbiological, and treatment data from the previous year were recorded.

ResultsOverall, 326 patients (48.5% females) were recruited: 185 adult and 141 pediatrics, with a median age [q3–q1] of 30 [38–24] and 12 [16–6] years, respectively. p.Phe508del mutation was present in 30.6% and 46.4% of patients with homozygosis or heterozygosis, respectively. Median FEV1 (%) was significantly lower in adults (62%, range 75–43%) compared with pediatrics (90%, range 104–81%) (p<0.001). Pancreatic insufficiency was observed in 77.3%, carbohydrate metabolism alteration in 27.3%, and CF-related diabetes in 19.6% of patients. Lower prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization were noted compared to 2013, along with a significantly lower correlation in lung function among pwCF colonized by P. aeruginosa (p<0.001). Half of pwCF (51%) exhibited a single pathogen in culture, two in 30%, and three or more in 2.4%. Co-colonization of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus (36.1%) was the most prevalent combination. High resistance rates were observed in P. aeruginosa and methicillin resistant S. aureus isolates.

ConclusionsWe provide a valuable and representative current insight into the observed evolution in the clinical, demographic, and microbiological aspects in recent years among pwCF in Spain.

Estudio de los patrones de colonización broncopulmonar en personas con fibrosis quística (pcFQ), recopilando datos clínicos, demográficos y microbiológicos para comparar los hallazgos del 2021 con un estudio multicéntrico similar realizado en 2013.

MétodosParticiparon 16 unidades de FQ de 14 hospitales españoles, reclutando aleatoriamente alrededor de 20 pacientes cada una. Los pacientes proporcionaron muestras de esputo, así como datos clínicos, demográficos, microbiológicos y de tratamiento del año anterior.

ResultadosSe reclutaron 326 pacientes (48,5% mujeres): 185 adultos y 141 pediátricos, con edad media (q3-q1) de 30 (38-24) y 12 (16-6) años, respectivamente. La mutación p.Phe508del estaba en 30,6% y 46,4% de los pacientes en homocigosis o heterocigosis, respectivamente. El FEV1 (%) medio fue menor en adultos (62% [75%-43%]) comparado con los pediátricos (90% [104%-81%]) (p<0,001). El 77,3% de los pcFQ presentaba insuficiencia pancreática, 27,3% alteración del metabolismo de los carbohidratos y el 19,6% diabetes asociada a la FQ. Hubo menor prevalencia de colonización por Staphylococcus aureus y Pseudomonas aeruginosa en comparación con 2013, y una correlación significativamente menor en la FEV1 entre los pcFQ colonizados por P. aeruginosa (p<0,001). El 51% de los pcFQ presentaron un patógeno en cultivo, dos el 30% y tres o más el 2,4%. La co-colonización de P. aeruginosa y S. aureus (36,1%) fue la más prevalente. Detectamos altas tasas de resistencia en P. aeruginosa y S. aureus resistente a meticilina.

ConclusionesProporcionamos una visión actual representativa de la evolución observada en los aspectos clínicos, demográficos y microbiológicos en los últimos años entre los pcFQ en España.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is one of the most common serious genetic diseases in the Caucasian population, the incidence of the disease being around one in every 5000–7000 births.1

Patient registries are essential in the study and management of CF as they enable disease monitoring, healthcare management, clinical research, and health policy planning.2 The first European CF registry was established in 2004 with the participation of only 6 European Union countries, while Spain did not participate in the registries until 2008.2 It was in 2017 (with 2016-year data) when the first CF registry was conducted in our country. The Spanish registry has been increasing the prevalence data of different CF microorganisms, but their susceptibility profiles to antimicrobials are not recorded. Furthermore, they do not relate the lung capacity of people with CF (pwCF) with the microorganisms that are detected by culture in their respiratory samples.3

We designed a multicentre study with a subset of pwCF representing different Autonomous Communities (AC) with specialized CF Units in Spain. Our first objective was to determine the prevalence of major CF pathogens as well as their antimicrobial susceptibility profiles. Second objectives included the acquisition of clinical and demographical data from pwCF and to decipher the correlation between patients’ lung function and clinical status with culture results from their respiratory samples. The third objective was to compare the results obtained from a prior similar multicentre study performed in 2013 with those obtained in this one, in order to know the evolution of the disease in our country.4

Material and methodsStudy designSixteen CF Units from 14 Spanish hospitals participated in this multicenter prospective study nine of them being adult units (>18 years) and seven being pediatric units (≤18 years). From February 2021 to December 2021, these units collected sputum samples and demographic data from 20 patients consecutively attended in their routine follow-up visits. Two centers sent a larger number of samples (n=22 and n=24), and we decided to include them in the study. Sputum samples were immediately frozen at −80°C and sent to the reference hospital (Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal) for microbiological processing. The ethics committees of each participant hospital approved the study (Ref. number 328/2020), and informed consent was provided to all patients and/or their parents or tutors.

Data collectionPatient demographic data, including age, gender, and CFTR mutation, were recorded. Lung function data focused on the best percentage predicted FEV1 (ppFEV1) from the prior year. FEV1 values were categorized as normal (>90%), mild (70–89%), moderate (40–69%), and severe (<40%) lung disease. Additional collected data included exacerbations, hospitalization days, antibiotic use (oral, inhaled, and intravenous), and CFTR modulator therapy over the past year.

Clinicians reported colonization/infection data of pathogens from the year before inclusion to determine the annual prevalence (AP) of CF pathogens. Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization status was classified using the modified Leeds criteria into chronic (>50% positive cultures), intermittent (≤50% positive cultures), and no colonization (negative cultures) based on at least four positive cultures from the last 12 month.5

Microbiological cultureThe sputa accumulated in the reference center were seeded to determine the point prevalence (PP) of CF pathogens and to study their susceptibility profile and epidemiology. Samples were kept frozen at −80°C until processing. To work on them, they were thawed overnight at 4°C, homogenized mechanically and cultured quantitatively following the recommendations of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology.6 Samples were seeded in general, selective and/or differential media (Fig. S1).

Identification of isolatesFor bacteria and yeasts, MALDI-TOF MS was used for species identification, and Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) was employed to determine the species within the Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC) isolates.7 Filamentous fungi were identified microscopically using lactophenol blue staining.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testingAgar disk-diffusion were used for S. aureus and P. aeruginosa isolates following the European Committee of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) criteria.8 The proportion of multidrug-resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR) and pandrug-resistant (PDR) P. aeruginosa strains was evaluated following the Magiorakos criteria.9 Susceptibility testing of BCC, Achromobacter xylosoxidans and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia isolates was studied by agar disk-diffusion following Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) criteria.10 For antibiotics lacking specific breakpoints for BCC, A. xylosoxidans and S. maltophilia, breakpoints designed for P. aeruginosa were applied.

Statistical analysisData from colonized versus non-colonized patients were compared using Mann–Whitney U-test. For qualitative variables, the Chi-squared or Fisher's exact test was used when applicable. The null hypothesis was rejected if our statistical analysis showed cut-off value below the significance level (0.05).

ResultsDemographical dataA total of 326 patients were included in the study being 48.5% females. The clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The most frequent mutation was F508del, present in 249 (76.4%) patients; 99 (30.6%) in homozygosis and 150 (46.4%) in heterozygosis. After F508del, the most frequent mutations were G542X and N1303K present in 5.7% and 3.2% of the chromosomes respectively (Table S1).

Clinical characteristics and demographical data.

| N° of patients | 326 |

| N° females (%) | 158 (48.5) |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean SD | 20 (10.8) |

| Range (q3–q1) | 31–12 |

| ≥18 years no. (%) | 185 (56.7) |

| <18 years no. (%) | 141 (43.2) |

| Mean FEV1% | 73.11 |

| FEV1in ≥18 years %a | 61.75 |

| Normal values n° (%) | 26 (14.1) |

| Mild disease n° (%) | 42 (22.8) |

| Moderate disease n° (%) | 83 (45.0) |

| Severe disease n° (%) | 33 (18.1) |

| FEV1in <18 years %b | 88.83 |

| Normal values n° (%) | 60 (52.6) |

| Mild disease n° (%) | 38 (33.4) |

| Moderate disease n° (%) | 13 (11.4) |

| Severe disease n° (%) | 3 (2.6) |

| Pulmonary exacerbationn° (%)c | 119 (36.5) |

| Median per patient [p75; p25] | 1 [2;1] |

| Hospitalization eventsn° (%)d | 23 (7) |

| Mean number of events per patient | 1.2 |

| Mean hospitalization dayse | 15 |

| Pancreatic insufficiencyn° (%)c | 252 (77.3) |

| Hidrocarbon intolerancen° (%)c | 89 (27.3) |

| Insulin therapyn° (%)d | 64 (19.6) |

Data available:

P. aeruginosa colonization status was defined as chronic, intermittent or absent in 30.1%, 17.4% and 52.4% patients, respectively. The corresponding figures for patients<18 years (n=142) were 43.6%, 33.8% and 22.5%, and for patients ≥18 years (n=185) were 45.1%, 13%, and 41.8% respectively.

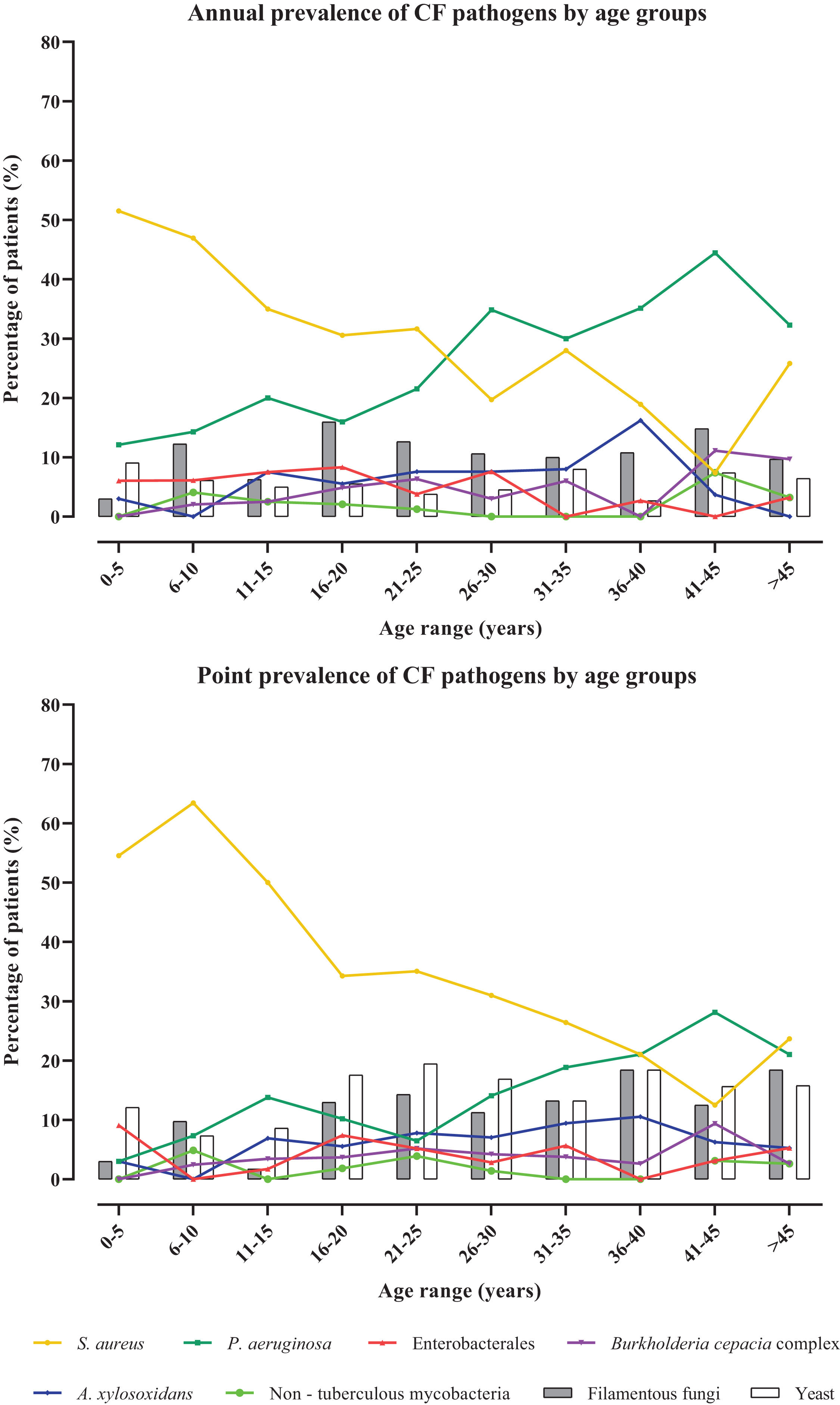

Colonization/infection patternsA total of 258 cultures were positive for any CF bacterial pathogen, 42 samples showed growth of bacteria from the normal oropharyngeal microbiota and in 26 samples no bacterial growth was observed. Considering both the AP and the PP approaches, the most common bacteria detected were S. aureus followed by P. aeruginosa (Table 2). S. aureus highest prevalence was detected in children under 10 years old. In contrast, the age range with the highest prevalence of P. aeruginosa was between 41 and 45 years old (Fig. 1). Notably, the difference in the prevalence of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus in adult and pediatric respiratory samples were statistically significant (p<0.0001 and p<0.0003) (Table S2). A. xylosoxidans and BCC were also more prevalent in samples obtained from adults, being more frequent in the 36–40 age groups and 41–45 respectively. Regarding BCC, the participating hospitals did not perform molecular characterization for species determination. Therefore, in our hospital the MLST determined that the most prevalent species of the BCC were B. cepacia and Burkholderia contaminans (33.3%; n=7) followed by Burkholderia multivorans (23.8%; n=5) and Burkholderia vietnamiensis (9%; n=2). No isolates of Burkholderia cenocepacia were detected.

Prevalence of different CF pathogens in pwCF of the study.

| 2013 | 2021 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP no. (%) | PP no (%) | AP no. (%) | PP no. (%) | |

| Bacteria | 339 (99) | 285 (84) | 304 (93.25) | 258 (79) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 234 (68.6) | 206 (60.4) | 186 (57) | 194 (59.5) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 212 (62.2) | 75 (22) | 140 (42.9) | 73 (22.39) |

| Achromobacter xylosoxidans | 39 (11.4) | 29 (8.5) | 37 (11.35) | 35 (10.74) |

| Burkholderia cepacia complex | 40 (11.8) | 16 (5) | 26 (7.98) | 21 (6.46) |

| Enterobacterales | 33 (9.7) | 9 (2.6) | 33 (10.12) | 24 (7.36) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 14 (4.1) | 0 (0) | 7 (2.1) | 0 (0) |

| Non-tuberculous mycobacteria | 9 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 11 (3.4) | 10 (3.1) |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 49 (13.8) | 26 (7.6) | 27 (8.2) | 18 (5.5) |

| Yeast | 96 (28.2) | 130 (38.1) | 33 (10.12) | 83 (25.46) |

| Candida albicans | 67 (19.6) | 71 (20.8) | 22 (6.7) | 55 (16.87) |

| Candida parapsilosis | 12 (3.5) | 49 (14.4) | 11 (3.3) | 28 (8.58) |

| Filamentous fungi | 101 (29.6) | 12 (3.5) | 68 (20.8) | 64 (19.63) |

| Exophiala spp. | 5 (1.5) | 8 (2.3) | 6 (1.8) | 11 (3.37) |

| Aspergillus spp. | 68 (17) | 4 (1.2) | 50 (15.3) | 23 (7.05) |

| Scedosporium spp. | 24 (7) | 2 (0.6) | 20 (6.1) | 4 (1.2) |

AP: annual prevalence; PP: point prevalence.

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) species obtained by the PP approach were Mycobacteroides abscessus (60%; n=6), Mycobacteroides avium (20%; n=2); Mycobacteroides lentiflavum (10%; n=1) and Mycobacteroides illarientze (10%; n=1). In contrast, only 2 species were detected by the AP approach, M. abscessus (63.6%; n=7) and M. avium (36.36%; n=4).

Comparing 2021 data with those obtained in 2013, we observed that, in general, AP and PP values decrease in 2021, highlighting the lower isolation of relevant CF pathogens, such as S. aureus and P. aeruginosa (Table 2).

Regarding fungal colonization, the AP and PP values were similar. However, the PP approach showed a higher prevalence of yeasts. More filamentous fungi were detected in older patients (>35 years) using PP data. The AP remained stable at 10% across all ages, with the Aspergillus fumigatus complex being the most frequent (Table 2). Both AP and PP of filamentous fungi and yeasts decreased in 2021, but the predominant species remained unchanged.

Co-colonizationHalf of the pwCF (n=166; 51%) had a positive culture for a single CF pathogen, 99 pwCF (30%) had the association of two pathogens and 8 (2.4%) pwCF had the association of three pathogens. The association of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus (n=36; 11%) were the most prevalent, followed by the association of S. aureus with A. xylosoxidans (n=25; 7.6%) (Fig. 2). Comparing the associations found in 2013 with those in 2021, we observe that they were quite similar, both in the number of patients with co-colonizations and in the combinations of the different pathogens.

Colonization patterns and pulmonary functionWe have a total of 298 patients (91.4%) of whom FEV1 data were available (Fig. S3). A total of 137 patients had P. aeruginosa colonization with FEV1 values (p.75–p.25) significantly lower than non-colonized patients [61% (79.5–42.5) vs. 85% (104–63.5)] (Fig. 3). When analyzing FEV1 values separately for adults and pediatrics with P. aeruginosa colonization, adults had significantly lower FEV1 values than pediatric patients [55.97% (71–40) vs. 78.20% (93.8–63.7)]. In the case of S. aureus, we obtained FEV1 data from 171 patients but in this case, we did not observe statistically significant differences between colonized and non-colonized [79% (95–56) vs. 67.5% (85–48.25)]. In addition, S. aureus non-colonized patients have a lower FEV1 value, which may be since 49.2% of them had a P. aeruginosa colonization. If we examine the FEV1 values while distinguishing between patients colonized by methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) [75% (86–45)] and those colonized by methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) [81% (97–60)], we observe a trend toward lower FEV1 values than those colonized by MRSA. However, this difference was not statistically significant.

If we carry out the same analysis with the exacerbations, we observe that the FEV1 of the 119 people with some exacerbation is significantly lower (p<0.001) 63.5% (87–44) than of those who have not had exacerbations 79% (94–59). A total of 61 pwCF had P. aeruginosa colonization and at least one exacerbation with an FEV1 of 51% (75–39). The difference in FEV1 of those with colonization but no exacerbation (n=79) is significantly higher 67.5% (81–41) with p<0.02. In the case of the 22 MRSA colonized patients, 13 of them have at least one exacerbation with a significantly lower lung capacity (57% [82–40]) than the 9 patients without exacerbations (79% [97–62]) p<0.001.

Antimicrobial susceptibility patternsA total of 79 P. aeruginosa isolates recovered from 72 patients were tested by disk diffusion method being 56% non-MDR, 11% MDR, 23% XDR and 10% PDR. The most active antibiotic was meropenem (78.5%) followed by ceftazidime (26.6%). Analyzing the activity of different antibiotics in MRSA, the most active ones were linezolid (96%) and co-trimoxazole (100%) (Table S3). In the BCC, fourteen isolates were tested, and we observed the best activity for meropenem (78.6%) and minocycline (71.4%). For A. xylosoxidans and S. maltophilia the most active antibiotics were piperacillin–tazobactam and ciprofloxacin respectively.

Analyzing the susceptibility of all microorganisms and comparing with those obtained in 2013, we observed a similar susceptibility pattern for all the cases and with a slight decrease in some cases. However, there was an exception with MRSA isolates showing an increase in resistance rates to gentamicin, rising from 16% to 42% (p=0.0047).

Antibiotic and non-antibiotic therapyA total of 279 (85.6%) pwCF have received an antibiotic treatment over the study period. The most common route of antibiotic administration was oral, followed by inhaled (Table S4). Notably, 21% of antibiotics with intravenous formulations were administered via inhalation, with vancomycin being the most frequently used (66.7%). Additionally, 82 patients (37.6%) received more than one inhaled antibiotic, often following a rotating schedule (72%). The most common combination of simultaneous administration of two inhaled antibiotics was colistin+aztreonam (13.3%).

A significant portion of patients received antibiotics through multiple routes of administration. The most common combination was oral+inhaled administration (50.9%), followed by inhaled+intravenous (22.1%), and oral+intravenous (19.9%). Antibiotics were administered by all three routes in 19% of the patients.

Immunomodulatory azithromycin was administered orally to 170 (52.1%) patients in the year prior to recruitment and it was significantly higher among those aged ≥18 years, with chronic P. aeruginosa colonization and with moderate-advanced disease (p<0.001). Other non-antibiotic therapies are shown in Table S5. Dornase-α administration was significantly higher in patients with moderate-severe disease versus patients with mild disease (p=0.0038). Inhaled glucocorticoids (IGC) and bronchodilators (BD) had no significant differences in administration based on age, disease severity, or P. aeruginosa colonization status, unlike 2013.11

Regarding CFTR modulators, they were used by 35.9% of the patients included in the study. The combination tezacaftor+ivacaftor was the most used modulator therapy (66.6%), followed by ivacaftor (14.5%) and lumacaftor+ivacaftor (6%). The newly approved modulator elexacaftor+tezacaftor+ivacaftor was administered to 14.5% of pwCF. These drugs were not used in 2013.

DiscussionNewborn screening programs and patient registry data collection have significantly improved in recent years.3,12,13 In the Spanish 2021 CF registry, 2578 patients were included, 56% of whom being adults (>18), a percentage like that of our study (56.5%). Recent European data, including Spain, show a stable prevalence of CF among children but a notable increase in adults. This trend reflects a consistent incidence rate and substantial improvements in patient survival, leading to a significant adult population rise.

The main CFTR protein variants (F508del, G542X, N1303K, and 2789+5G->A) observed in our study align with those in the European registry as well as the rate of pancreatic insufficiency (77.3%).11 However, we observed less exacerbations and hospitalizations compared to 2013 data, with a 9-day reduction in hospital stays possibly linked to CFTR modulator treatments being initiated.14

A 50% reduction in the PP of P. aeruginosa could be attributable to the intermittent colonization observed in some patients (17.4%), a trend also observed in 2013 and remaining similar (Fig. S2). The prevalence of P. aeruginosa detected in 2021 (42.9%) was lower than that detected in 2013 (62.2%).4 Similarly, the proportion of chronic colonized patients were 16% lower than that detected in 2013 but similar to that reported by the ECFS for Spain (38%) in 2021.12S. aureus prevalence was very similar to that reported by the ECFS registry in 2021 but significant differences exist between European countries that may reflect methodological differences in sample processing.15 As with P. aeruginosa, the AP of S. aureus was 10% lower in 2021 (Table 2). These differences could be explained by the improvement in patient's management or the implementation of newborn screening after 2013.16,17

In our study, the AP of BCC was 7.3%, lower than that in 2013 (11.8%) but still high, indicating a significant deviation from the expected prevalence compared to other European countries.12 It is of note that 45.8% (11/24) of the patients presenting BCC colonization in the year prior to the study came from a single hospital of Spain. Excluding this hospital, the prevalence was 4%, more aligned with European data. B. contaminans and B. cepacia were the most commonly identified BCC species, consistent with recent published data for this microorganism in Spain.18,19 Bacterial pathogens such as S. maltophilia and A. xylosoxidans showed similar values from other CF studies.20

Our findings confirm a varied distribution of M. avium and M. abscessus infections among patients, with M. avium predominantly affecting adults (mean age 29.7 years) and M. abscessus showing a trend toward younger patients (mean age 20.3 years).21

The detection rates of filamentous fungi in both AP and PP were similar, consistent with previous findings.20 Yeast prevalence in PP doubled AP, likely due to under-reporting in centers not recognizing them as CF pathogens. Significantly lower PP rates for A. fumigatus and S. apiospermum may stem from the study's sputum-freezing protocol affecting culture viability. However, E. dermatiditis detection was higher in PP probably due to extended incubation periods.22

As expected, the most prevalent co-colonization was P. aeruginosa with S. aureus.23 Studies have been identified both in the same lobe of CF lungs, suggesting that both pathogens are present in the same niche and may indeed interact in vivo.23,24

This study confirms the known negative correlation between lung function and colonization by pathogens like P. aeruginosa and/or MRSA (Fig. 3).25 Among pwCF, those colonized by P. aeruginosa or both P. aeruginosa and S. aureus had significantly lower lung function compared to non-colonized individuals (p<0.001 and p=0.004, respectively). Interestingly, pwCF colonized by both major pathogens, had higher FEV1 compared to those colonized solely by P. aeruginosa (p=0.0047), possibly influenced by age differences between the cohorts [19 (30–15) vs. 31 (41–25) years] (Fig. 3). The lack of significant differences in MRSA colonization may stem from its smaller sample size (n=22) compared to MSSA isolates (n=172), and many S. aureus colonized patients presents P. aeruginosa.

Comparing 2021 and 2013 data, we did not detected variation in P. aeruginosa isolates exhibiting a MDR phenotype, but there was an increase in the percentage of XDR and PDR phenotypes. The 99% of the patients who had chronic colonization by P. aeruginosa received oral (71.1%), inhaled (98%) or intravenous (35.7%) antibiotics.26S. aureus isolates showed high macrolide resistance rates (39.4%), consistent with prior Spanish studies.4 MRSA displayed rising gentamicin resistance linked to the aac(6′)-aph(2″) gene within a mobile genetic element (non-published data), potentially transferred to S. aureus.27 Notably, 60% of patients with gentamicin-resistant MRSA had used aminoglycosides via inhalation or intravenously. The resistance rates of A. xylosoxidans and S. maltophilia were higher than previously reported.28

Regarding modulator therapies, we observed a low use of triple therapy compared to dual or monotherapy with modulators. This was expected, as the administration of triple CFTR modulator therapy (Kaftrio®) to adult CF patients did not start until the end of 2021, and in younger populations until 2022.29 Yet, we observed an important use of Kaftrio® (14.5%), probably administered on compassionate use. Moreover, in 60% of these patients, the ppFEV1 was below 50%, with an overall mean of 64.13% (90–39).

Our study presents limitations. The number of recruited patients was lower than that obtained in 2013 mainly due to COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, restrictive measures that were introduced during the pandemic may have caused a potential bias, positively decreasing the number of bacterial transmissions.30 Nevertheless, the data obtained are fully representative and in line with Spanish Registry data, so they probably address in a truthful way the evolution of CF disease in our country.

In conclusion, this multicenter study focused on investigating the current state of CF microbiology and its relationship with the FEV1 in pwCF. Additionally, a decrease in the prevalence of the main microorganisms over the last years were observed.

Funding of the researchThis study was supported by Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Infecciosas (CIBERINFEC) (CB21/13/00084 and CB21/13/00099) co-financed by the European Development Regional Fund ‘A way to achieve Europe’ (ERDF) and PI19/01043 project, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain. AM-A is supported by a pre-doctoral contract associated to PI19/01043 project.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare not to have any conflicts of interest that may be considered to influence directly or indirectly the content of the manuscript.

Artificial intelligence involvementNo material has been produced with the help of artificial intelligence.

Members of the Spanish Cystic Fibrosis Study Group GEIFQ (Grupo Español para el Estudio de la Colonización/Infección Broncopulmonar en Fibrosis Quística).