Listeria monocytogenes is the causative agent of listeriosis, a food-borne disease that mainly affects pregnant women, the elderly, and immunocompromised patients. The primary treatment of choice of listeriosis is the combination of ampicillin or penicillin G, with an aminoglycoside, classically gentamicin. The second-choice therapy for patients allergic to β-lactams is the combination of trimethoprim with a sulfonamide (such as co-trimoxazole). The aim of this study was to analyze the antimicrobial susceptibility profile of strains isolated from human infections and food during the last two decades in Argentina.

MethodsThe minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 8 antimicrobial agents was determined for a set of 250 strains of L. monocytogenes isolated in Argentina during the period 1992–2012. Food-borne and human isolates were included in this study. The antibiotics tested were ampicillin, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, erythromycin, gentamicin, penicillin G, tetracycline and rifampicin. Breakpoints for penicillin G, ampicillin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were those given in the CLSI for L. monocytogenes. CLSI criteria for staphylococci were applied to the other antimicrobial agents tested. Strains were serotyped by PCR, and confirmed by an agglutination method.

ResultsStrains recovered from human listeriosis patients showed a prevalence of serotype 4b (71%), with the remaining 29% corresponding to serotype 1/2b. Serotypes among food isolates were distributed as 62% serotype 1/2b and 38% serotype 4b. All antimicrobial agents showed good activity.

ConclusionThe strains of L. monocytogenes isolated in Argentina over a period of 20 years remain susceptible to antimicrobial agents, and that susceptibility pattern has not changed during this period.

Listeria monocytogenes es el agente etiológico de la listeriosis, una enfermedad transmitida por los alimentos que afecta principalmente a las mujeres embarazadas, los ancianos y pacientes inmunocomprometidos. El tratamiento antibiótico de elección es la combinación de ampicilina o penicilina G con un aminoglucósido; generalmente gentamicina. La segunda opción de terapia para los pacientes alérgicos a los beta-lactámicos es la asociación de trimetoprima con una sulfonamida (cotrimoxazol). El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar el perfil de susceptibilidad antimicrobiana de las cepas aisladas de infección invasiva humana y de alimentos durante las dos últimas décadas en la Argentina. Métodos: Se determinó la concentración inhibitoria mínima (CIM) de 8 agentes antimicrobianos en 250 cepas de L .monocytogenes aisladas durante el período 1992-2012. Se incluyeron aislamientos de origen humano y de alimentos. Los antibióticos ensayados fueron: ampicilina, cloranfenicol, cotrimoxazol, eritromicina, gentamicina, penicilina G, tetraciclina y rifampicina. El criterio de interpretación utilizado fue el indicado por el CLSI. Los aislamientos fueron serotipificados por PCR y por el método de aglutinación.

ResultadosLos aislamientos humanos se distribuyeron con una prevalencia del serotipo 4b (71%); el 29% restante correspondió al serotipo 1/2b. Los aislamientos de alimentos correspondieron: 62% serotipo al serotipo 1/2b y 38% al serotipo 4b. Todos los agentes antimicrobianos mostraron buena actividad.

ConclusiónLas cepas de L. monocytogenes aisladas en Argentina durante un período de 20 años siguen siendo susceptibles a los agentes antimicrobianos y dicho patrón de susceptibilidad no ha cambiado durante este período.

Listeria monocytogenes is a ubiquitous bacterium widely distributed in the environment. It causes a severe, life-threatening infection called listeriosis that affects mainly immunodepressed patients, pregnant women, newborns and the elderly. The central nervous system is the most frequent site involved. Clinical presentation of listeriosis ranges from mild influenza-like illness to meningitis, septicaemia or meningoencephalitis.1 Most forms of listeriosis in humans result from food-borne transmission1 and numerous outbreaks occurring worldwide in the last decade could be linked to contaminated food. Listeriosis represents a public health problem since it is fatal in up to 30% or leads to neurologic sequelae among survivors.2,3

L. monocytogenes is susceptible to a wide range of classes of antibiotics active against Gram positive bacteria.3,4 The pattern of antibiotic susceptibility and resistance of Listeria spp. has been stable for many years.5,6 However, some studies have reported an increased rate of resistance to one or several clinically relevant antibiotics in food and environmental isolates7–10 and less frequently in clinical strains.6,11,12

This retrospective study was performed in order to evaluate the antibiotic susceptibility of human disease-related L. monocytogenes strains and food strains isolated since 1990 in Argentina, in order to assess the emergence of resistance, and to establish the first database with patterns of susceptibility and resistance to antimicrobial agents currently used in human therapy of strains of L. monocytogenes isolated in the country.

MethodsBacterial strainsThe strains were collected at the Special Bacteriology Division, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Buenos Aires, since 1992. A test set of 250 strains was selected from a collection of more than 500 isolates from food and human listeriosis cases isolated from several provinces of Argentina.

Of these, 157 strains were recovered from human invasive listeriosis. Ninety-three strains from various types of food were randomly selected (45% raw meat, 18% ready-to-eat food, 30% sausages, 4% soft cheese, 3% vegetables).

Identification and serotypingPhenotypic identification was carried out as described previously.3 Strains were assigned to major serovars by multiplex-PCR13 and serotype was confirmed by the traditional agglutination method using a commercial kit and following manufacturer's recommendations (Denka Seinken).

Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) determinationAll antimicrobial agents were obtained from their respective manufacturers as known potency powders. The antibiotics used were (concentration range in μg/ml): penicillin G (0.03–32μg/ml), ampicillin (0.03–32μg/ml), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (0.03/32–0.06/608μg/ml), gentamicin (0.03–32μg/ml), erythromycin (0.03–32μg/ml), tetracycline (0.06–64μg/ml), chloramphenicol (1–1024μg/ml) and rifampin (0.015–16μg/ml). MIC was determined by broth microdilution method according to the recommendations of the CLSI14,15 using cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton broth (CAMHB, Difco Laboratories) supplemented with 5% lysed horse blood. In the total required incubation time of 48h (35°C), antibiotic-containing microtiter plates were read at 24h and 48h. The lowest concentration of drug that inhibited the bacterial growth after incubation for 24hours was considered the MIC. No changes were noted at 48h reading. Quality control was ensured by testing Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 49619 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213.

Evaluation of susceptibilityBreakpoints for aminopenicillins, penicillin G and co-trimoxazole are given in the CLSI.14 To establish sensitivity to the rest of the antimicrobial drugs, we applied the breakpoint defined by CLSI for staphylococci as described in previous reports.15,16

ResultsSerotyping of strains recovered from human listeriosis patients (n=157) showed a prevalence of serotype 4b (71%); the remaining 29% corresponded to serotype 1/2b.

Serotypes among food isolates (n=93) were distributed as 62% serotype 1/2b and 38% serotype 4b.

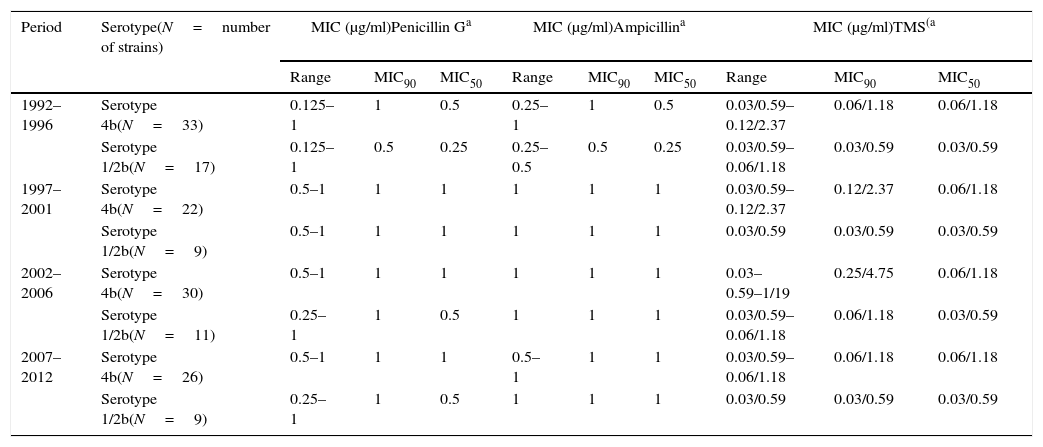

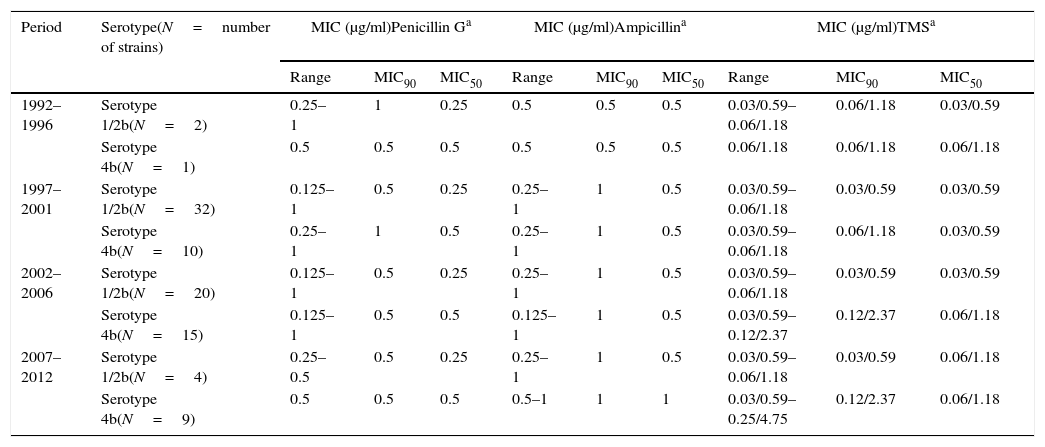

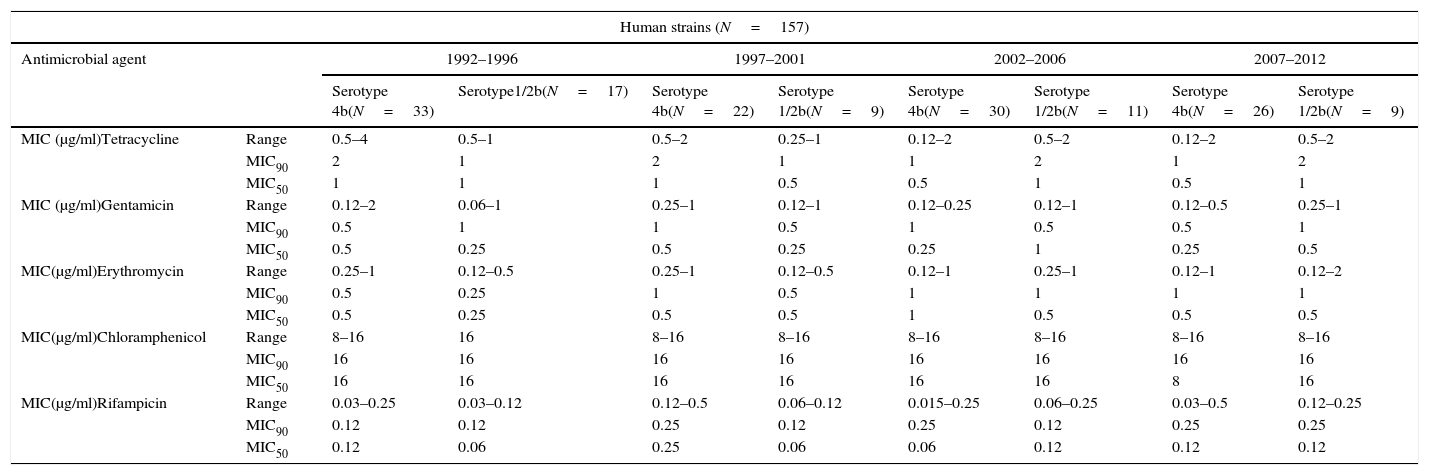

The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC), MIC50 (where 50% of bacteria were inhibited) and MIC90 were calculated to describe the in vitro antimicrobial activity against L. monocytogenes isolates. All strains analyzed were susceptible to ampicillin, penicillin, trimetoprim-sulfamethoxazole, gentamicin, tetracycline and rifampicin. Intermediate resistance profile was observed for chloramphenicol in 73% of human isolates and in 95% of food-borne strains and for erythromycin in 30% of human strains and 45% of food isolates. No remarkable differences were detected in the MIC values among serovars. Results are presented in Tables 1a, 1b and 2.

MIC values from clinical strains for antimicrobial agents with CLSI defined breakpoints.

| Period | Serotype(N=number of strains) | MIC (μg/ml)Penicillin Ga | MIC (μg/ml)Ampicillina | MIC (μg/ml)TMS(a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | MIC90 | MIC50 | Range | MIC90 | MIC50 | Range | MIC90 | MIC50 | ||

| 1992–1996 | Serotype 4b(N=33) | 0.125–1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25–1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.03/0.59–0.12/2.37 | 0.06/1.18 | 0.06/1.18 |

| Serotype 1/2b(N=17) | 0.125–1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25–0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.03/0.59–0.06/1.18 | 0.03/0.59 | 0.03/0.59 | |

| 1997–2001 | Serotype 4b(N=22) | 0.5–1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.03/0.59–0.12/2.37 | 0.12/2.37 | 0.06/1.18 |

| Serotype 1/2b(N=9) | 0.5–1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.03/0.59 | 0.03/0.59 | 0.03/0.59 | |

| 2002–2006 | Serotype 4b(N=30) | 0.5–1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.03–0.59–1/19 | 0.25/4.75 | 0.06/1.18 |

| Serotype 1/2b(N=11) | 0.25–1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.03/0.59–0.06/1.18 | 0.06/1.18 | 0.03/0.59 | |

| 2007–2012 | Serotype 4b(N=26) | 0.5–1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5–1 | 1 | 1 | 0.03/0.59–0.06/1.18 | 0.06/1.18 | 0.06/1.18 |

| Serotype 1/2b(N=9) | 0.25–1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.03/0.59 | 0.03/0.59 | 0.03/0.59 | |

MIC values from foorborne strains for antimicrobial agents with CLSI defined breakpoints.

| Period | Serotype(N=number of strains) | MIC (μg/ml)Penicillin Ga | MIC (μg/ml)Ampicillina | MIC (μg/ml)TMSa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | MIC90 | MIC50 | Range | MIC90 | MIC50 | Range | MIC90 | MIC50 | ||

| 1992–1996 | Serotype 1/2b(N=2) | 0.25–1 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.03/0.59–0.06/1.18 | 0.06/1.18 | 0.03/0.59 |

| Serotype 4b(N=1) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.06/1.18 | 0.06/1.18 | 0.06/1.18 | |

| 1997–2001 | Serotype 1/2b(N=32) | 0.125–1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25–1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.03/0.59–0.06/1.18 | 0.03/0.59 | 0.03/0.59 |

| Serotype 4b(N=10) | 0.25–1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25–1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.03/0.59–0.06/1.18 | 0.06/1.18 | 0.03/0.59 | |

| 2002–2006 | Serotype 1/2b(N=20) | 0.125–1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25–1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.03/0.59–0.06/1.18 | 0.03/0.59 | 0.03/0.59 |

| Serotype 4b(N=15) | 0.125–1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.125–1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.03/0.59–0.12/2.37 | 0.12/2.37 | 0.06/1.18 | |

| 2007–2012 | Serotype 1/2b(N=4) | 0.25–0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25–1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.03/0.59–0.06/1.18 | 0.03/0.59 | 0.06/1.18 |

| Serotype 4b(N=9) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5–1 | 1 | 1 | 0.03/0.59–0.25/4.75 | 0.12/2.37 | 0.06/1.18 | |

MIC values from clinical strains for antimicrobial agents with no defined CLSI breakpoints.

| Human strains (N=157) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial agent | 1992–1996 | 1997–2001 | 2002–2006 | 2007–2012 | |||||

| Serotype 4b(N=33) | Serotype1/2b(N=17) | Serotype 4b(N=22) | Serotype 1/2b(N=9) | Serotype 4b(N=30) | Serotype 1/2b(N=11) | Serotype 4b(N=26) | Serotype 1/2b(N=9) | ||

| MIC (μg/ml)Tetracycline | Range | 0.5–4 | 0.5–1 | 0.5–2 | 0.25–1 | 0.12–2 | 0.5–2 | 0.12–2 | 0.5–2 |

| MIC90 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| MIC50 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| MIC (μg/ml)Gentamicin | Range | 0.12–2 | 0.06–1 | 0.25–1 | 0.12–1 | 0.12–0.25 | 0.12–1 | 0.12–0.5 | 0.25–1 |

| MIC90 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| MIC50 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |

| MIC(μg/ml)Erythromycin | Range | 0.25–1 | 0.12–0.5 | 0.25–1 | 0.12–0.5 | 0.12–1 | 0.25–1 | 0.12–1 | 0.12–2 |

| MIC90 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| MIC50 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| MIC(μg/ml)Chloramphenicol | Range | 8–16 | 16 | 8–16 | 8–16 | 8–16 | 8–16 | 8–16 | 8–16 |

| MIC90 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | |

| MIC50 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 16 | |

| MIC(μg/ml)Rifampicin | Range | 0.03–0.25 | 0.03–0.12 | 0.12–0.5 | 0.06–0.12 | 0.015–0.25 | 0.06–0.25 | 0.03–0.5 | 0.12–0.25 |

| MIC90 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| MIC50 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | |

| Food strains (N=93) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial agent | 1992–1996 | 1997–2001 | 2002–2006 | 2007–2012 | |||||

| Serotype 4b(N=1) | Serotype1/2b(N=2) | Serotype 4b(N=10) | Serotype 1/2b(N=32) | Serotype 4b(N=15) | Serotype 1/2b(N=20) | Serotype 4b(N=9) | Serotype 1/2b(N=4) | ||

| MIC (μg/ml)Tetracycline | Range | 1 | 0.5–1 | 0.25–1 | 0.25–1 | 0.25–2 | 0.5–1 | 0.5–1 | 0.5–1 |

| MIC90 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| MIC50 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| MIC (μg/ml)Gentamicin | Range | 0.5 | 0.25–0.5 | 0.25–1 | 0.06–1 | 0.12–1 | 0.25–0.5 | 0.25–1 | 0.12–0.25 |

| MIC90 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | |

| MIC50 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | |

| MIC (μg/ml)Erythromycin | Range | 1 | 0.5–1 | 0.25–1 | 0.12–2 | 0.25–1 | 0.25–1 | 0.5–1 | 0.5–1 |

| MIC90 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| MIC50 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| MIC (μg/ml)Chloramphenicol | Range | 16 | 16 | 8–16 | 1–16 | 8–16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| MIC90 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | |

| MIC50 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | |

| MIC (μg/ml)Rifampicin | Range | 0.12 | 0.12–0.25 | 0.03–0.12 | 0.015–0.25 | 0.03–0.12 | 0.06–0.25 | 0.06–0.12 | 0.06 |

| MIC90 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.06 | |

| MIC50 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

The high susceptibility of human and food isolates to penicillin, ampicillin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was evident in this study. Similar results were also observed in other reports.5–7,12 This study also highlighted the sensitivity to tretracycline, contrasting with the emergence of tetracycline resistance related to gene tetM reported worldwide.11,17 No resistance to the association of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was observed, which is important considering it represents the second-choice therapy in the treatment of listeriosis.4

These results showed that the strains of L. monocytogenes isolated in Argentina over a period of 20 years remain susceptible to antimicrobial agents used in the treatment of listeriosis and that their susceptibility pattern has not changed during this period. The results agree with previous studies held in Europe, US and Latin America.5,9,12,18,19

Recently, the susceptibility to antibiotics of a large collection of clinical strains isolated since 1926 in France was studied. They described the first clinical isolate with high-level resistance to trimethoprim, and they claimed to reinforce the need for clinical microbiological surveillance due to the recent increase in penicillin MICs up to 2μg/ml.11

Therefore, we propose to establish a program of continuous monitoring of antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates of L. monocytogenes isolated from humans, animal, food and environmental sources in our country. Future studies will focus on the surveillance of resistance emergence in a larger collection of food-borne and animal isolates of L. monocytogenes and Listeria spp. in Argentina.

FundingThis work was supported by the regular federal budget of the National Ministry of Health of Argentina.

Conflict of interestsNone.