Gastrointestinal motility disorders are highly prevalent. There have been advances in the understanding of these disorders but despite this, some aspects of its pathophysiology remain unknown. Several procedures are available and have proven to be useful for the diagnosis of gastrointestinal dysmotility, including manometry, pH-metry and non-invasive testing such as scintigraphy and regional and whole-gut transit studies. Although most of the times, gastrointestinal motility disorders are diagnosed with above mentioned procedures, occasionally, they are challenging and require of invasive assisted-procedures that are usually helpful in the diagnosis of these particular difficult scenarios. In these complicated situations endoscopy-assisted motility procedures may become relevant for their correct assessment and diagnosis. Endoscopy departments need to be aware of these procedures and collaborate with gastrointestinal motility physicians on this challenging endeavor. This paper will review the role of the endoscopy in the evaluation of gastrointestinal motility disorders.

Los trastornos de la motilidad gastrointestinal son muy frecuentes. Ha habido avances en la comprensión de estos trastornos, pero a pesar de ello, algunos aspectos de su fisiopatología siguen siendo desconocidos. Varios procedimientos están disponibles y han demostrado ser útiles para el diagnóstico de los trastornos de la motilidad gastrointestinal, incluyendo manometría, pHmetría y pruebas no invasivas, tales como gammagrafía y estudio regional y general de tránsito intestinal. Aunque la mayoría de las veces, los trastornos de la motilidad gastrointestinal son diagnosticados con los procedimientos mencionados anteriormente, en ocasiones, su diagnóstico es evasivo y difícil, requiriendo de procedimientos invasivos y asistidos que suelen ser útiles para su diagnóstico, particularmente en estas situaciones. En escenarios complicados, los estudios de motilidad asistidos por endoscopia, adquieren relevancia para una correcta evaluación y diagnóstico. Los departamentos de endoscopia deben conocer estos procedimientos y colaborar con los médicos especialistas en la motilidad gastrointestinal en esta tarea desafiante. En este artículo se revisará el papel de la endoscopia en la evaluación de los trastornos de la motilidad gastrointestinal.

Introduction

Diagnosis of gastrointestinal motility disorders (GIMD) is most of the times straight forward with current available technology. However there are complex motility disorders that may represent a challenge in their diagnostic approach. These difficulties are in part due to a lower prevalence of complicated GIMD but also as a result of their diffuse distribution along the gastrointestinal tract and this scenario requires of more complex diagnostic tools. Procedures performed in the gastrointestinal motility laboratory are addressed to assess physiology of the gastrointestinal tract with both, stationary and ambulatory techniques that require invasive and assisted procedures in order to provide comprehensive information that might impact in the management and prognosis of a particular situation. Endoscopic procedures are highly important in the diagnosis and treatment of GIMD.1 Occasionally, there are some difficulties to place catheters or probes by conventional techniques as a result of poor patient tolerance, anatomic variability or technical issues. These problems, although not common, require a dedicated endoscopy unit with well-trained personal capable to solve above mentioned problems in order to complete the motility procedure. Also, there are diagnostic tests that require hybrid procedures in the assessment of GIMD. These kinds of procedures require high level of skills and expertise as well as a specialized gastrointestinal motility laboratory and endoscopy unit. Hence, communication between neurogastroenterologists and endoscopists is necessary to perform these meaningful procedures by applying a correct endoscopic technique to get good quality data for interpretation.

Currently, these procedures are performed in selected cases and only in few tertiary care centers. Nevertheless, it is necessary to know both, clinical indications and proper technique for implementation of these procedures. This paper aims to describe indications, techniques and outcomes of endoscopy-assisted procedures in the evaluation of GIMD and to provide a better understanding about these useful techniques that are not widely known.

Esophageal manometry

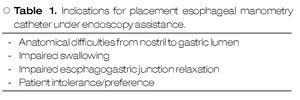

Esophageal manometry (EM) is a useful procedure in the evaluation of the upper esophageal sphincter (EUS), esophageal body and lower esophageal sphincter (LES). This procedure was introduced back in 1950's for the assessment of intraluminal esophageal pressures.2 Since then, EM has experienced changes, partly due to differences in technique but also because of technological advances that have impacted in the investigation of esophageal physiology.2-4 Despite above mentioned advances, there are certain circumstances that may represent technical difficulties in esophageal manometry catheter placement. It is in those cases when endoscopy may assist for the correct catheter placement (Figure 1). Indications for endoscopy-assisted placement of EM catheter are summarized in Table 1.

○ Figure 1. First, after a complete inspection, a guide wire is advanced into the stomach A), and then the endoscope is withdrawn leaving the guide wire in place B). The manometry catheter is passed over the guide wire C) and finally guide wire is removed after the catheter is completely inserted D).

Although there are different EM catheters, endoscopy-assisted EM is performed with a water-perfused catheter that holds an internal channel through which a guide wire is introduced for correct catheter placement.

Procedure

It is always recommended to perform a regular upper endoscopic evaluation before catheter placement. Sometimes, this evaluation will discover previously important and unnoticed information as a result of well know inter-observer variability,5,6 but also findings secondary to the underlying motility disorder or to other unsuspected esophageal pathology as in pseudoachalasia.7,8 Additional endoscopic information may be necessary for a better correlation with manometric and clinical data. Examples of these can be found in the esophagus (ie, Zenker diverticulum, esophagogastric junction tumors), stomach (ie, bezoars) and duodenum (ie, diverticulum).

Patients with suspected esophageal dysmotility are required to fast at least eight to 12 hrs before the endoscopy procedure. Reason to do so is because these patients may have fluid and food retention into the esophagus as a result of achalasia or into the stomach in severe gastroparesis. It is recommended to place the patient in the left lateral position, with 45 degrees inclination to avoid aspiration.

Sedation during this procedure is not recommended unless this is absolutely necessary. Reason to avoid sedation during endoscopy-assisted EM is related to the risk of aspiration that may be high in this patient population. Also, sedation may change pressure profiles in UES, LES and esophageal body. This is especially true with the use of benzodiazepines and opioids.9-11 If sedation is required, then the manometric procedure needs to be deferred at least two to three hours after the endoscopy evaluation has finished. An additional reason to perform consciousness manometric evaluation is because it requires patient cooperation to perform several maneuvers as swallowing in a coordinated manner.

After finishing full endoscopic evaluation, endoscope is held distally in gastric antrum and a guide wire is passed through the working channel and advanced (Figure 1). After the guide is fully visible, then the endoscope can be pulled out carefully in a coordinated manner while the guide wire is continuously advanced. Air suction is important while the endoscope is removed to promote wall collapse by decreasing gastric lumen size that will minimize the need of excessive guide wire insertion and also to decrease patient discomfort. Once endoscope is at mouth, an assistant holds the guide wire while the endoscope is fully withdrawn.

Esophageal catheter is placed either in the endoscopy suite or in the motility laboratory, depending on equipment availability because the manometry catheter needs to be calibrated and connected to the pneumohydraulic pump before patient's intubation in order to obtain accurate data. Then, the EM catheter is passed through the guide wire using a specially designed port. In this case, the catheter is obviously inserted thru the oral cavity instead the nostril. The catheter is advanced up to 65 cms from the tip to make sure that all sensors are into the stomach. After this, patient is asked to lie on his back, horizontally and manometric recordings can begin.

Clinical impact

Information coming from manometry is both, significant and clinically relevant. As a result of this intervention, decisions are made for patient management. Endoscopy-assisted EM is usually performed in highly selective population as in achalasia in which correct diagnosis will lead to a specific treatment.12 Less clear are the impact of these results for unspecific motility disorders; however the intrinsic value of manometry is to rule out motility disorders with well-established treatment.

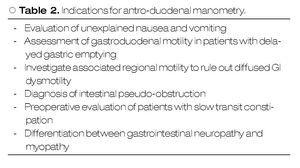

Antroduodenal manometry

Gastric and duodenal motility are governed by a complex neural signaling to achieve coordinated smooth muscle contraction. Antroduodenal manometry is of particular interest in the diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal motility disorders as gastroparesis, antroduodenal hypomotility and intestinal pseudo-obstruction.13,14 Antroduodenal manometry provides the pathophysiological basis on patient's symptoms that ultimately will lead to a better diagnosis and treatment. Antroduodenal manometry is indicated for the evaluation of patient with unexplained upper abdominal symptoms. Indications for antroduodenal manometry are listed in Table 2.

Procedure

Patients should fast at least 8 hours before the procedure to prevent aspiration. This is also necessary for a better assessment of antroduodenal resting motor activity which is crucial for the differentiation of normal and pathological motility patterns either for tonic or phasic gastroduodenal activity. Patients should avoid taking medications that potentially affect gastrointestinal motility such as prokinetics, narcotics and some antidepressants (anticholinergic effect) at least 48 hours before the procedure.

Antroduodenal manometry catheters might be water-perfused or solid-state. Each of them require of special recorders for data acquisition that determine study characteristics as well as its duration. Water-perfused catheters are connected to a stationary pneumohydraulic compressor which pumps water at low rate but constant flow throughout a variable number of capillaries distributed along the catheter. Because of this, water-perfused catheters restrict data acquisition to the motility laboratory and for a limited period of time. Solid-state catheters have multiple recording sensors located at different distances between each other (Figure 2). The advantage of these catheters is that they allow longer recording periods in an ambulatory setting.

○ Figure 2. Solid-state antroduodenal catheter.

The test consist in at least three to six hours resting recordings (fasting) in order to detect motor migrating complexes that are generally present every 90 min. Fasting period is followed by a meal and/or a provocative test (erythromycin, octreotide) that may provide information regarding frequency, intensity and coordination of motor complex.

Endoscopy-assisted antroduodenal manometry reduces prolonged radiation exposure and decreases the time for catheter placing.

Water-perfused catheters are placed with endoscopy assistance. After conventional endoscopic assessment, the endoscope is placed as distally as possible in the duodenum. A guide wire is advanced through the working channel as distal as possible while the endoscope is withdrawn carefully. Guide wire position can be monitored by fluoroscopy before the endoscope has been completely withdrawn. This is followed by introduction of water-perfused catheter throughout the guide wire and advanced until a suitable position. Position is then confirmed by fluoroscopy before removing the guide wire. A final x-ray is recommended after the guide wire has been removed.

Solid-state catheters are only placed in the endoscopy suite. Before being placed, a silk thread is tied close to the tip of the catheter. After this, catheter is advanced through nostril into the stomach. Subsequently, endoscope is carefully advanced into the stomach. The tip of the catheter is localized by the endoscope and the silk thread is grasped by a polipectomy snare or with biopsy forceps and then introduced into the working channel, about 2-3 cm. It is recommended to use only mild distention in order to obtain a better field of vision. The endoscope and the catheter are pushed in as distally as possible and once in the duodenum, the catheter is advanced distally using the polipectomy snare and by pushing the silk thread. At this stage, position is assessed by fluoroscopy and once position is confirmed, the silk thread is released, the polypectomy snare is pulled back to the working channel and the endoscope is carefully removed while insufflated air is removed. Air suction will promote gastric and intestinal wall collapse reducing the chance of catheter migration. Finally, an x-ray is performed to assess the catheter's optimal placement.

In water-perfused catheters, the patient is positioned close to the pneumohydraulic pump in which the catheter is connected in order to proceed with study recording. Solid-state catheters are connected to a recording device that is used by the patients during the study, to obtain 24-hour recordings in the outpatient setting.

Clinical Impact

Results of antroduodenal manometry may change diagnosis of patients referred for the assessment of unexplained/refractory nausea, vomiting and/or abdominal pain in up to 15% to 20%.15,16

Antroduodenal manometry can be helpful in the assessment of partial small bowel obstruction. In one study, patients referred with suspected partial obstruction, 25% were normal and therefore surgical intervention was not necessary. An obstructive pattern was diagnosed in 22% which eventually required surgical treatment and in the remaining 50% of patients the diagnosis was intestinal pseudo-obstruction and as a result of this test, optimal medical treatment was provided in this patients.17 In patients diagnosed with intestinal pseudo-obstruction, a provocative test (tegaserod, erythromycin, octreotide) may be useful in order to assess response to treatment.18-20 Finally, antro-duodenal manometry is useful in the evaluation of hypersensitivity and impaired gastric relaxation in patients with functional dyspepsia, leading to the prescription of tricyclic antidepressants and specific serotonin agonists (type 1 receptor) respectively.21

Sphincter of oddi manometry

Sphincter of Oddi is located at second portion of the duodenum. Its main function is to regulate the output of biliopancreatic secretions and prevention of intestinal reflux. This sphincter consists of smooth muscle that is radially arrayed in a complex anatomical conformation.22 This sphincter may exhibit an increase resting tone and spastic contractions that lead to obstruction of biliary and pancreatic flow resulting in abdominal pain. Obstruction is also the cause of elevated liver enzymes and ducts dilation. All features mentioned above are considered diagnostic criteria for Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD).23 Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction is classified in three types23,24

Indication

In presence of classical triad (pain, elevated enzymes, dilation) as is in type I SOD, manometry is not indicated since sphincterotomy is considered the standard treatment.25,26 In type II SOD, a manometric assessment is clearly indicated to guide the need of sphincterotomy.25,27 In type III patients, manometry can be considered to further clarify whether abdominal pain is related to SOD or with a functional disorder.28

Procedure

This procedure is performed as part of ERCP which offers the advantage of a therapeutic intervention in the presence of abnormal results.29 SOM catheters can be water-perfused or solid-state. Water-perfused catheters are 200 cm long and may have a variable number of pressure sensors. Some catheters have a special port to use a guide wire that facilitates cannulation of pancreatic and biliary ducts. These catheters are connected to a water compressor which pumps water throughout capillaries. Pressure changes are then transduced by a polygraph system which in turn is connected to a computer, allowing data recording and its analysis. Data are acquired by the pull-through technique, using multiple pressure sensors located at the catheter and an average pressure is then calculated for each particular point of interest (biliary and/ or pancreatic). Catheter can be selectively positioned in either the biliary or pancreatic duct. Usually is not necessary to perform biliary and pancreatic measurements in the same patient, avoiding the risk of multiple cannulations and excessive manipulation of the sphincter. The decision to selectively cannulate will be determined by clinical findings.

Solid-state catheters are 4F or 5F in diameter and have three sensors located between each other at 90 degrees and at different positions from the tip. These catheters are introduced with the assistance of a guide wire (Figure 3). Data is also acquired with the pull-through technique. The catheter is connected to a receiver which in turn is connected to a computer where data is recorded and analyzed. There are some differences between both catheters regarding data acquisition and safety profile. One study compared solid-state versus water-perfused catheters and showed a low frequency in pancreatitis incidence using solid-state catheters (3.1% vs 13.8%).30 Some reports have showed a diminished risk of pancreatitis by using water-perfused catheters when water is aspirated during the manometric procedure through a specially designed port.31 Regarding accuracy in data acquisition, both water-perfused and solid-state catheters have good correlation in pressure measurements.

○ Figure 3. This picture shows SOD cannulation with a solid-state manometry catheter.

Clinical Impact

A positive test (resting pressure >40mmHg) can lead to therapeutic intervention in 50% to 65% of type II patients and in 12% to 60% of type III. This intervention is beneficial in 85% of type II and in 55-60% of type III patients.25,26,32,33 There may be an association between Idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis and a hypertensive sphincter with reported prevalences around 15% to 72%. Sphincterotomy resulted in prevention of pancreatitis outbreaks in up to 60% to 80% of these patients.34

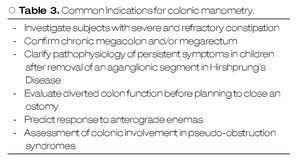

Colonic manometry

Colonic manometry is a procedure that allows qualitative and quantitative measurement of intraluminal pressure of the colon and rectum.35 It provides information about baseline colonic pressure and also about characteristic pressure patterns (high amplitude propagating contractions) either after a physiological (after meals, after waking) or provocative stimuli (bisacodyl, balloon distention) which in turn have clinical relevance in the assessment of colonic motor disorders. Colonic manometry is a standard test for chronic constipation assessment in pediatric patients in the USA. In adults, although it has proven to be useful, this test is performed just in few tertiary care centers.

Indications

Indications for intraluminal colonic motility assessment in adults differ in some aspects to those for children. Recently, the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society published a consensus statement on intraluminal measurement of gastrointestinal and colonic motility.1 Indications for colonic manometry are showed in Table 3.

Procedure

Colonic manometry catheters show differences in length and number of recording sensors. Usually, there are six to eight sensors spaced between them from 5 to 20 cm. High resolution colonic manometry is now available and provides an increased number of recording sites.36

Typically, placement of colonic manometry catheter is performed using a retrograde approach assisted by colonoscopy. A conventional colonic preparation is required for this procedure but is sometimes difficult due to the severe constipation in this patient population. A clear liquid diet is indicated 48 hours before the procedure and polyethylene glycol solution is provided a day before the procedure as is usually provided in each patient for a conventional colonoscopy.

There are two different types of catheters: water-perfused and solid-state. Water-perfused catheter is connected to a pneumohydraulic pump and therefore is a stationary procedure. A colonoscopic evaluation is always recommended prior catheter placement. Once in the cecum, a guide wire is inserted through the working channel and advanced while the colonoscope is carefully withdrawn whereas the colon is decompressed by removing air excess. Next, the water-perfused catheter is advanced over the guide wire under fluoroscopic control. Once catheter location is confirmed, the guide wire is removed and the catheter is taped to the gluteus.

Solid-state catheter is connected to a data receiver and therefore suitable for ambulatory studies. A silk thread is tied close to the tip. The thread is grasped by a polypectomy snare or biopsy forceps and subsequently is introduced through the working channel in about 2-3 cm. Thus, the catheter is located alongside the colonoscope and then both are carefully inserted and advanced with minimal air insufflation. Once in the desired position, the silk thread is released from polypectomy snare/forceps. Peristalsis may promote catheter migration, especially during 24 hours monitoring. Catheter can be anchored to the colonic mucosa by conventional endo-clips using the silk thread tied to the tip of the catheter.37 It has been shown that this may prevent catheter displacement (Figure 4). Colonoscope is withdrawn carefully while air is aspirated. Finally, the catheter is taped to the gluteal area and an abdominal x-ray is obtained to confirm catheter position.

○ Figure 4. The picture shows a solid-state colonic manometry during the anchoring process to the colonic wall by using an endo-clip.

There are several techniques for colonic manometry, including anterograde (nasal intubation) which is time consuming and usually not practical.38 Colonic manometry can be performed under radiologic control throughout an appendicostomy or cecostomy39 if necessary.

Clinical impact

Colonic manometry provides meaningful information regarding pathophysiology of colonic dysfunction. Patients with colonic neuropathy tend to have disorganized motility patterns as well as lower number of high-amplitude propagated contractions. These patients may be referred for surgical treatment whereas patients with a myopathic pattern, exhibit organized motility patterns but with low amplitude and may respond to aggressive medical treatment.40 Rao et al, showed successful response one year after colectomy in 70% of patients who exhibited a neuropathic pattern while in patients with myopathy, 50% of patients responded to conservative treatment.41

In children, colonic manometry is helpful in predicting response to anterograde enemas usually after a favorable response with bisacodyl stimulation.42 It has been shown that colonic manometry is useful for the assessment of colonic function before reconnecting a previously diverted colon.43

Additional procedures

Endoscopy may assist other motility procedures, either in the research field or as a treatment of procedure-related complications.

Ileocecal valve has been subject of investigation, in part because of its role as a physical barrier to prevent cecoileal reflux and bacterial overgrowth. Ileocecal valve manometry is performed with a water-perfused catheter that is placed through the colonoscopy working channel. Once the catheter is placed in the terminal ileum, a resting pressure is recorded, followed by cecal distention by insufflating air through the colonoscope. This insufflation triggers a reflex that subsequently is recorded. Clinical significance of ileocecal manometry is unknown.44

Endoscopy may be helpful in the treatment of complications as is the retention of a wireless motility capsule. Although infrequent, a wireless motility capsule can be retained in a patient with severe delay of gastrointestinal transit or as a result of an unsuspected stenosis. Endoscopy may help to avoid a surgery because of the potential risk of perforation or bleeding induced by the retained capsule.45

Conclusion

Endoscopy-assisted motility procedures are commonly indicated in patients with severe gastrointestinal motility disorders usually after that multiple trials of treatments have failed. These patients have a poor quality of life and frequently they undergo to several diagnostic procedures during their symptoms assessment which in turn increase health related expenses. These procedures provide useful diagnostic information to motility disorders that ultimately may lead to an adequate treatment which is crucial for symptomatic relief in this patient population.

Correspondence:

Enrique Coss-Adame, MD.

Section of Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Georgia Health Sciences University.

BBR 2535B, 1120 15th Street Augusta, GA.

Z.P. 30912.

E-mail:ecossadame@georgia-health.edu