Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) managed in both hospital and out-ofhospital settings usually have a high/very high cardiovascular risk, with a high burden of cardiovascular disease. All this justifies that the reduction of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol is the main therapeutic goal in T2DM. However, residual cardiovascular risk is very prevalent in T2DM, and is usually associated with atherogenic dyslipidemia and hyperlipoproteinemia(a); therefore, it is also necessary to reverse these lipoprotein abnormalities to achieve effective cardiovascular prevention. Given the considerable armamentarium of lipid-lowering drugs currently available, the Cardiovascular Disease Working Group of the Spanish Diabetes Society has considered it appropriate to carry out a narrative review and update of the effectiveness of these lipid-lowering drugs in the population with T2DM taking into account their effect on the lipoprotein profile and their potential impact on glycemic control.

Los pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (DM2) atendidos tanto en el ámbito hospitalario como extrahospitalario suelen presentar un alto/muy alto riesgo cardiovascular, con una elevada carga de enfermedad cardiovascular. Todo ello justifica que la reducción del colesterol de las lipoproteínas de baja densidad sea el principal objetivo terapéutico en la DM2. Sin embargo, el riesgo cardiovascular residual es muy prevalente en los sujetos con DM2, y suele asociarse a la dislipemia aterogénica y a la hiperlipoproteinemia(a); por tanto, es necesario revertir también estas anomalías lipoproteicas para conseguir una prevención cardiovascular eficaz.

Dado el considerable armamentario de fármacos hipolipemiantes disponibles en la actualidad, el Grupo de Trabajo de Enfermedad Cardiovascular de la Sociedad Española de Diabetes ha considerado oportuno realizar una revisión narrativa y actualización de la eficacia de dichos fármacos en la población con DM2, teniendo en cuenta su efecto en el perfil lipoproteico y su potencial impacto en el control glucémico.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), with its various clinical signs (coronary, cerebrovascular, and peripheral arterial disease), is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1 Additionally, according to data from both hospital and primary care settings, the Spanish population with T2DM is primarily at very high/high cardiovascular risk.2,3 To reduce this risk, the 2019 European clinical practice guidelines on cardiovascular prevention4 recommend that reducing low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol should be the primary therapeutic goal in the management of T2DM. However, it also highlights that cholesterol not carried by high-density lipoproteins (HDL) and apolipoprotein (apo) B levels are secondary targets of special interest in individuals with T2DM or atherogenic dyslipidemia. If a lipid profile below the recommended targets could be achieved and maintained solely through a healthy lifestyle, the benefit would be immense. In this regard, we refer the reader to national evidence from the Mediterranean Diet Prevention studies (PREDIMED) and the Coronary Diet Intervention with Olive Oil and Cardiovascular Prevention (CORDIOPREV) for primary and secondary prevention of CVD, respectively. However, the current rates of childhood diabesity and metabolic syndrome generate inevitable skepticism about the capacity to correct and/or improve lifestyles in industrialized societies.

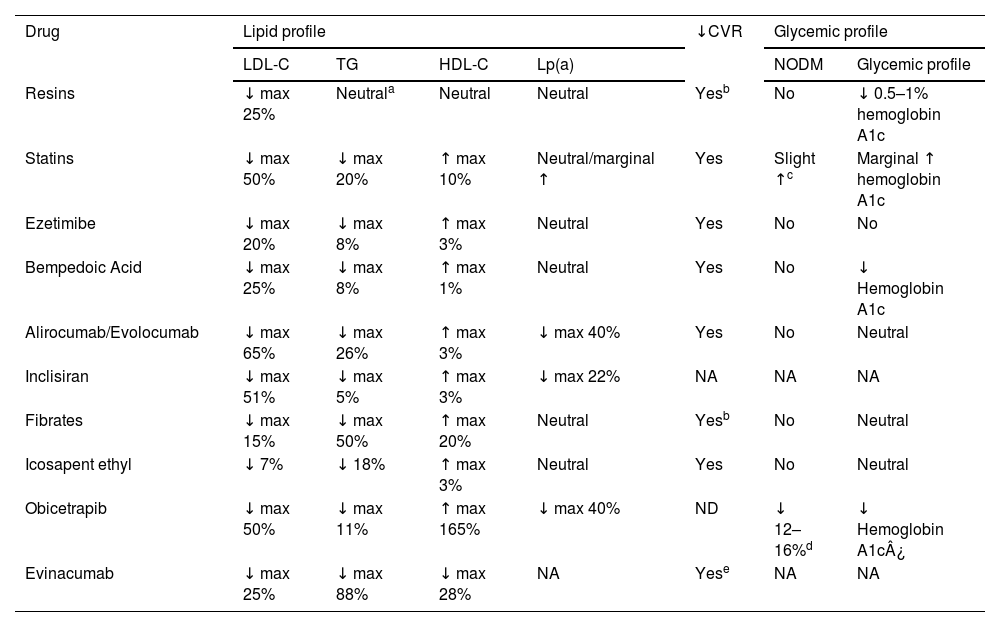

Over the past decade, new lipid-lowering drugs have emerged that could help reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events in people with T2DM. We should mention that the higher cardiovascular risk of individuals with T2DM makes them a population group particularly benefited by lipid-lowering treatments. The Cardiovascular Disease Working Group of the Spanish Diabetes Society deemed it appropriate to update the efficacy profile of these treatments and, in terms of safety, specifically address their potential impact not only on lipid metabolism but also on carbohydrate metabolism. Table 1 outlines the effects of the main lipid-lowering drugs on the lipid profile, cardiovascular risk, and glycemia.

Effect of the main lipid-lowering drugs on the lipid, glycemic profile, and cardiovascular risk.

| Drug | Lipid profile | ↓CVR | Glycemic profile | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDL-C | TG | HDL-C | Lp(a) | NODM | Glycemic profile | ||

| Resins | ↓ max 25% | Neutrala | Neutral | Neutral | Yesb | No | ↓ 0.5–1% hemoglobin A1c |

| Statins | ↓ max 50% | ↓ max 20% | ↑ max 10% | Neutral/marginal ↑ | Yes | Slight ↑c | Marginal ↑ hemoglobin A1c |

| Ezetimibe | ↓ max 20% | ↓ max 8% | ↑ max 3% | Neutral | Yes | No | No |

| Bempedoic Acid | ↓ max 25% | ↓ max 8% | ↑ max 1% | Neutral | Yes | No | ↓ Hemoglobin A1c |

| Alirocumab/Evolocumab | ↓ max 65% | ↓ max 26% | ↑ max 3% | ↓ max 40% | Yes | No | Neutral |

| Inclisiran | ↓ max 51% | ↓ max 5% | ↑ max 3% | ↓ max 22% | NA | NA | NA |

| Fibrates | ↓ max 15% | ↓ max 50% | ↑ max 20% | Neutral | Yesb | No | Neutral |

| Icosapent ethyl | ↓ 7% | ↓ 18% | ↑ max 3% | Neutral | Yes | No | Neutral |

| Obicetrapib | ↓ max 50% | ↓ max 11% | ↑ max 165% | ↓ max 40% | ND | ↓ 12–16%d | ↓ Hemoglobin A1c¿ |

| Evinacumab | ↓ max 25% | ↓ max 88% | ↓ max 28% | NA | Yese | NA | NA |

LDL-C: Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; TG: Triglycerides; HDL-C: High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; Lp(a): Lipoprotein(a); CVR: Cardiovascular Risk; NODM: New-Onset Diabetes Mellitus; NA: Not Available; A1c: Glycated Hemoglobin.

Ion exchange resins are hypocholesterolemic drugs with more than 60 years of experience. Currently, resincolestyramine, colestipol, and colesevelam are available. They act in the small intestine by binding to bile acids, causing their fecal elimination and, consequently, interrupting the enterohepatic cycle (Fig. 1). The bile acids that are excessively eliminated are replaced by the liver through the oxidation of a greater amount of cholesterol via a chain of reactions controlled by the enzyme cholesterol-7-alpha-hydroxylase. The decrease in the hepatic cholesterol pool causes, on the one hand, an increase in the activity of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase and, on the other hand, an increase in hepatic cholesterol uptake due to the increase in LDL receptor synthesis. However, the increased hepatic cholesterol synthesis may promote an increase in the secretion of very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), consequently aggravating any preexisting hypertriglyceridemia.5

Resins are drugs that are not absorbed and, therefore, have no systemic effects. For this reason, they are considered the safest hypolipidemic drugs for use in pregnant women. Their main drawback is that they must be administered separately from other drugs as they can interfere with their absorption. Although their side effects are not severe, they are usually bothersome enough for patients to the extent that compliance rates are often low. The main side effects are gastrointestinal, including gastric intolerance and changes in intestinal rhythm.

Bile acid sequestrants have been shown to reduce fasting glucose levels and hemoglobin A1c levels. In this regard, colesevelam can decrease hemoglobin A1c levels by approximately 0.5%–1.0% in patients already on other hypoglycemic drugs such as metformin, sulfonylureas, and insulin.6 Based on these studies, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology7 published an algorithm for blood glucose control in the treatment of T2DM, in which colesevelam is included as another therapeutic option. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved its indication in 2009 for improving glucose control in T2DM patients. Although several hypotheses have been proposed, the mechanism by which resins improve glucose metabolism remains unclear. Currently, the side effects of resins, polypharmacy in DM2 patients, and the frequent hypertriglyceridemia characteristic of atherogenic dyslipidemia, along with the availability of new pharmacological options, limit their use.

StatinsStatins are the first-line therapy for reducing plasma LDL cholesterol concentrations. According to the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists meta-analysis,8 in people with diabetes, a 1 mmol/L (∼40 mg/dL) reduction in LDL cholesterol with statins led to a 21% reduction in major cardiovascular events. It is well known that statins are associated with a risk of new-onset diabetes; however, this diabetogenic effect should not diminish their undeniable cardiovascular benefits. It has been estimated that 1 additional case of diabetes occurs per 1000 person-years of statin exposure, while 5 cardiovascular deaths are prevented.9 Of note, the diabetogenic effect of statins is more pronounced in individuals with risk factors for diabetes, primarily components of metabolic syndrome. While several theories have been proposed, the mechanisms responsible for statin-induced diabetes remain unknown.10 Initially believed to be a class effect, it has been demonstrated that not all statins equally affect glucose metabolism. For instance, a prospective study of 1269 patients with glucose intolerance found an 18% reduction in the cumulative incidence of diabetes with pitavastatin vs the control group undergoing lifestyle changes alone (odds ratio [OR], 0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.68–0.99; p = 0.041).11 Additionally, the meta-analysis by Vallejo-Vaz et al.12 concluded that pitavastatin is not associated with new-onset diabetes; thus, its use has been recommended in individuals at high risk of diabetes, prediabetes, or T2DM.13

EzetimibeEzetimibe, an inhibitor of intestinal cholesterol absorption (Fig. 1), is often used in combination with statins to achieve greater LDL cholesterol reductions without increasing adverse effects. It carries no diabetogenic risk.14 Moreover, in the Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial (IMPROVE-IT), ezetimibe combined with simvastatin was more effective in cardiovascular prevention in the subgroup of patients with T2DM, for the same LDL cholesterol reduction.15

Although statins are necessary to reduce cardiovascular risk in T2DM patients, there is increasing emphasis on considering combination therapy of moderate-/high-intensity statins at submaximal doses with ezetimibe rather than high-dose statin monotherapy. In patients with CVD, combined therapy with moderate-intensity statins and ezetimibe was shown to be non-inferior to high-intensity statin monotherapy for a 3-year composite cardiovascular endpoint of cardiovascular death, major cardiovascular events, or non-fatal stroke, with a higher achievement rate of LDL cholesterol targets and fewer instances of statin dose reduction or discontinuation.16 This benefit was observed even in the diabetic population.17 In conclusion, combined therapy is recommended to effectively reduce LDL cholesterol while mitigating the potential risk of suboptimal metabolic control associated with high-dose statin therapy.

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) plays a fundamental role in intracellular cholesterol homeostasis by promoting the degradation of LDL receptors in the lysosomes of hepatocytes. PCSK9 inhibition results in an increased number of LDL receptors on hepatocyte membranes, consequently enhancing the catabolism of LDL particles (Fig. 1). PCSK9 is also expressed in other tissues, including endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells, suggesting that its inhibition could have local effects as well.18 Over the past 20 years, drugs have been developed to reduce peripheral PCSK9 concentration or its binding to the LDL receptor through different mechanisms or technologies: monoclonal antibodies, small interfering ribonucleic acid (siRNA), adnectins, and even vaccines or occasional changes in the PCSK9 gene sequence.

The two monoclonal antibodies available for PCSK9, alirocumab and evolocumab, reduce LDL cholesterol levels by 50–65% and lipoprotein(a) (Lp[a]) by 20–30%.19,20 Mendelian randomization studies have revealed that genetic variants with effects similar to PCSK9 inhibitors are associated with a higher risk of diabetes or hyperglycemia.21 However, these findings have not been corroborated by clinical studies,22,23 likely because the binding of monoclonal antibodies to PCSK9 occurs extracellularly.

Inclisiran, approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2020 and the FDA in 2021, is a double-stranded siRNA targeting PCSK9, administered every 6 months (after an initial dose and a follow-up dose at 3 months). It reduces LDL cholesterol by 50% and Lp(a) by up to 25%.24 This cholesterol-lowering effect is independent of glycemic status,25 and it is maintained over time.26 Currently, 3 clinical trials are evaluating the potential cardiovascular benefits of inclisiran.

Overall, these drugs targeting PCSK9 (monoclonal antibodies and siRNA) are highly effective in reducing LDL cholesterol and cardiovascular risk, with an excellent safety profile, especially in individuals with T2DM. However, studies with longer exposure to inclisiran are needed to document the absence of an increased risk of new-onset diabetes.

Bempedoic acidIn 2020, the FDA and EMA approved a new oral lipid-lowering agent, bempedoic acid, which inhibits adenosine triphosphate-citrate lyase (ACL), an enzyme involved in cholesterol synthesis located 2 metabolic steps upstream of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase (Fig. 1). It is a prodrug activated intracellularly by its conversion to bempedoic acid-CoA through very-long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase-1 (ACSVL1), which is expressed primarily in hepatocytes and, to a lesser extent, in renal cells, but is absent in adipose and muscle tissues. Bempedoic acid reduced LDL cholesterol concentrations by 17.4%–28.5%.27 Additionally, it significantly lowered hemoglobin A1c by 0.12% and 0.06% in individuals with T2DM and prediabetes, respectively. The annual rate of new-onset diabetes in normoglycemic or prediabetic individuals did not increase in the bempedoic acid group compared to the placebo group (0.3% vs. 0.8% and 4.7% vs. 5.9%, respectively).28 The drug efficacy profile in reducing LDL cholesterol was independent of glycemic status. Moreover, the Mendelian randomization study by Ference et al.29 found no association between mutations in the gene encoding ACL and T2DM. In the Cholesterol Lowering via Bempedoic Acid, an ACL-Inhibiting Regimen (CLEAR) Outcomes study,30 involving statin-intolerant patients, treatment with bempedoic acid for 40.6 months showed a significant 13% reduction in cardiovascular event risk. Among the study participants, 45% had T2DM, and no metabolic deterioration or new-onset diabetes was observed in the active treatment group.31 A pooled analysis of 4 phase 3 studies suggested that bempedoic acid is a suitable therapy for patients with metabolic syndrome requiring additional LDL cholesterol reduction.32 Bempedoic acid is considered a safe drug, although it is associated with an increased risk of gout, particularly in those with a history of the condition, as well as a slight, transient rise in serum creatinine and uric acid levels.

In conclusion, bempedoic acid effectively reduces LDL cholesterol and cardiovascular risk with good tolerability and a neutral-to-positive effect on glycemic parameters. Despite this, T2DM without CVD is not a criterion for reimbursement of bempedoic acid under the Spanish health care system, according to the therapeutic positioning report (TPR) of the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Health Products (AEMPS).

Therapies targeting diabetic dyslipidemiaBeyond LDL cholesterol, residual cardiovascular risk remains very high in individuals with T2DM and is often associated with the atherogenic dyslipidemia characteristic of this disease. This dyslipidemia is marked by elevated triglyceride concentrations, low HDL cholesterol levels, and normal or slightly elevated LDL cholesterol levels, but with a predominance of small, dense LDL particles. Of note, apo B-containing lipoproteins, such as LDL, VLDL, intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL), and Lp(a), are atherogenic, especially those with a diameter <70 nm, allowing them to easily penetrate the arterial wall, deposit in the extracellular matrix of the subendothelial space, and initiate atherogenesis. Unfortunately, evidence reveals that diabetic dyslipidemia is underdiagnosed, undertreated, and consequently, poorly controlled.33,34

Fibrates and niacinClinical intervention studies with triglyceride-lowering drugs, such as extended-release niacin with laropiprant35,36 and fibrates,37,38 have not demonstrated cardiovascular benefits when added to conventional treatment, including statins. Favorable evidence has only emerged from post-hoc analyses of patients with atherogenic dyslipidemia or its components treated with fibrates.39,40 Recently, in the Pemafibrate to Reduce Cardiovascular Outcomes by Reducing Triglycerides in Patients with Diabetes (PROMINENT) study,41 which included a total of 10,497 individuals with diabetic dyslipidemia and LDL cholesterol levels ≤100 mg/dL, pemafibrate—a selective modulator of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α—had a neutral impact on cardiovascular endpoints. This was likely because, although it reduced triglyceride levels by 25%, it did not decrease circulating atherogenic lipoprotein concentrations.

Thus, while there is consensus on the use of fibrates to prevent acute pancreatitis risk in severe hypertriglyceridemia, their use in cardiovascular prevention for patients with mild-to-moderate hypertriglyceridemia remains controversial.

Omega-3 fatty acidsRegarding omega-3 fatty acids, randomized clinical trials combining eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) at low doses (1 g/day) such as the Outcome Reduction with an Initial Glargine Intervention (ORIGIN),42 A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes (ASCEND),43 and Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL),44 or at 4 g/day in the Long-Term Outcomes Study to Assess Statin Residual Risk with Epanova in High Cardiovascular Risk Patients with Hypertriglyceridemia (STRENGTH),45 as well as a meta-analysis46 involving 77,917 individuals across 10 studies—9 of which used a combination of EPA + DHA—did not demonstrate cardiovascular protective effects in patients concurrently undergoing statin therapy.

In the Japan EPA Lipid Intervention Study (JELIS),47 a total of 8645 hypercholesterolemic Japanese patients were randomly treated with low-intensity statins plus 1.8 g/day of EPA or statins alone. There was a 19% reduction in the risk of major coronary events in the EPA + statin group. Years later, the Reduction of Cardiovascular Events with Icosapent Ethyl–Intervention Trial (REDUCE-IT)48 indicated that a dose of 4 g/day of icosapent ethyl reduced the risk of ischemic events, including cardiovascular death, in patients on statins who had LDL cholesterol levels of 41 up to 100 mg/dL (1.06 up to 2.59 mmol/L) and triglycerides between 135 and 499 mg/dL (1.52–5.63 mmol/L), with established cardiovascular disease or T2DM with, at least, 1 risk factor. The robust findings of REDUCE-IT and its prespecified subanalyses have been reflected in the inclusion of icosapent ethyl in secondary prevention treatment algorithms in various guidelines for managing dyslipidemia.

Mechanistic studies of plaque regression have also confirmed that icosapent ethyl is associated with significant improvements in the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of coronary atheromas49 and coronary physiology.50

Regarding the safety profile of icosapent ethyl, adverse events were equally distributed across both therapeutic arms, regardless of severity. In the REDUCE-IT study, there was an observed increase in treatment-related adverse hemorrhagic episodes (mild and severe) (11.8% vs. 9.9%, p = 0.006). However, the rate of severe hemorrhagic episodes, including hemorrhagic stroke, other severe central nervous system hemorrhages, and GI bleeding did not significantly increase in the icosapent ethyl group. Moreover, in a subgroup of patients with acute coronary syndrome receiving dual antiplatelet therapy, no increase in severe bleeding events was noted. Additionally, while the hospitalization rate for atrial fibrillation or flutter was higher in the icosapent ethyl group (3.1% vs 2.1%, p = 0.004), the risk of stroke was lower (OR, 0.72; 95%CI, 0.55−0.93; p = 0.01). Icosapent ethyl is only contraindicated in patients with hypersensitivity to the active ingredient, soy, or any of its excipients.

According to the TPR, icosapent ethyl at a dose of 2 g every 12 h is funded for patients with CVD and LDL cholesterol <100 mg/dL and triglycerides >150 mg/dL. A recent subanalysis of the REDUCE-IT study51 in statin-treated patients with metabolic syndrome showed that icosapent ethyl reduced the risk of cardiovascular events. These findings support the use of icosapent ethyl as a potential therapeutic option in high cardiovascular risk patients with metabolic syndrome.

New therapiesInhibitors of cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP)Cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) is a plasma glycoprotein secreted by the liver that mediates the bidirectional transfer of cholesteryl esters and triglycerides between lipoproteins. This results in a net transfer of cholesteryl esters from HDL to VLDL and LDL, and triglycerides from VLDL to LDL and HDL. Inhibiting CETP reduces these exchanges, leading to enrichment of HDL with cholesteryl esters and a decrease in those of apoB-containing lipoproteins, ie, VLDL and LDL.

Although first-generation CETP inhibitors such as torcetrapib, dalcetrapib, and evacetrapib significantly increased HDL cholesterol levels, they did not demonstrate cardioprotective effects. However, in the Randomized Evaluation of the Effects of Anacetrapib through Lipid Modification (REVEAL) study,52 in CVD patients on statins, a 104% increase in HDL cholesterol was accompanied by a 17% decrease in LDL cholesterol and a 9% reduction in major coronary events at a 4.1-year follow-up. This relative risk reduction was consistent with the size of the reduction in LDL or non-HDL cholesterol. This drug was not submitted for regulatory approval, partly due to its accumulation in adipose tissue from high lipophilicity. Subsequently, a meta-analysis demonstrated that next-generation CETP inhibitors were associated with a reduced risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality.53

CETP inhibition—beyond changing the transfer of cholesteryl esters from HDL to apoB-containing lipoproteins—may also increase transintestinal cholesterol excretion, thereby enhancing fecal sterol excretion and increasing the expression of scavenger receptor class B type 1 and hepatic LDL receptors. Additionally, increased catabolism of LDL and apoB has been demonstrated, providing the main metabolic basis for their reduced plasma concentrations. Therefore, the LDL receptor pathway may also be positively regulated by CETP inhibition.

Obicetrapib is a new-generation CETP inhibitor whose clinical development includes 9 phase 1 studies in healthy volunteers, 6 completed phase 2 studies in patients with dyslipidemia or elevated lipoprotein(a) (Lp[a]), and 3 ongoing phase 3 trials.54 Collectively, these studies have shown that obicetrapib at low daily oral doses reduces LDL cholesterol by 50%, non-HDL cholesterol by 44%, apoB by 30%, and Lp(a) by 40%. It also reduces LDL particles, particularly small and dense ones, and increases pre-β HDL, mature HDL, apoA-1, and apoE. These effects are evident with obicetrapib as monotherapy and in combination with statins and ezetimibe, with excellent tolerance and safety profiles.54

A 12% reduction in the risk of new-onset diabetes55 and a 16% reduction56 in fasting glucose levels in both diabetic and non-diabetic individuals have been documented with CETP inhibitors (prior to obicetrapib) vs placebo. In March 2022, the Cardiovascular Outcome Study to Evaluate the Effect of Obicetrapib in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease (PREVAIL) was launched to evaluate the potential of obicetrapib (10 mg/day) in reducing major cardiovascular events, including cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, and non-elective coronary revascularization.

ApoC-III targeted therapyApoC-III plays a crucial role in the metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRLs) through both lipoprotein lipase (LPL)-dependent and independent mechanisms. Its plasma concentration is directly and linearly associated with triglyceridemia and increases in conditions of insulin resistance. Moreover, at pancreatic level, apoC-III has been shown to interfere with the functionality and survival of beta cells. Hyperglycemia in individuals with T1DM or T2DM is also associated with higher apoC-III57 concentrations, and this increase appears to contribute to atherogenic dyslipidemia.58

Volanesorsen, an antisense oligonucleotide targeting apoC-III, has been effective in reducing triglyceridemia in individuals with monogenic and polygenic chylomicronemia,59 including 40% of participants with T2DM,60 as well as in those with familial partial lipodystrophy, hypertriglyceridemia, and diabetes.61 Due to side effects, particularly thrombocytopenia, volanesorsen has not been approved by the FDA but has been approved by the EMA and is available for use in Spain for patients with familial chylomicronemia. ApoC-III is subject to post-translational changes, some of which, such as the proteoform with 2 sialic acid molecules, are associated with lower triglyceride concentrations.62 It is not yet clear to what extent these changes can modulate pharmacological interventions targeting apoC-III.

Two drugs are currently in the pipeline. Olezarsen is an antisense oligonucleotide conjugated with N-acetylgalactosamine, enhancing hepatic selectivity and potentially being more effective and safer than volanesorsen. In a phase II study with 114 patients with moderate hypertriglyceridemia, subcutaneous administration achieved reductions in triglycerides of up to 60% and apoB of up to 16%, with no changes in renal or hepatic function or platelet count. These results are better than those obtained with fibrates and could translate into a long-term reduction in vascular events.

Secondly, Plozasiran RNAi could achieve similar efficacy.

Directed therapy against angiopoietin-like protein 3Angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3), synthesized exclusively in the liver, can increase VLDL secretion and inhibit the activity of 2 extracellular lipases: LPL, consequently reducing the catabolism of TRLs, and endothelial lipase, which leads to a decrease in hepatic LDL uptake. In 2021, the EMA and FDA approved the first human monoclonal anti-ANGPTL3 antibody, evinacumab, for use in homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HoFH). Long-term and real-world use of evinacumab, as an adjuvant to lipid-lowering strategies—including LDL apheresis—resulted in sustained LDL cholesterol reduction and improved survival cardiovascular event-free in patients with HoFH.63 The mechanism of action of evinacumab is not dependent on the LDL receptor pathway, which is absent or inefficient in HoFH, but instead promotes TRL catabolism and remnant particle clearance, preventing their transformation into LDL through an endothelial lipase-dependent mechanism.

Due to evinacumab high efficacy profile in reducing triglycerides, 2 Phase II studies were conducted in participants with mild-to-moderate hypertriglyceridemia and LDL cholesterol ≥ 100 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L), randomized to evinacumab at different doses or placebo. Results were very promising for lipid profile improvements, with good tolerance and no severe adverse effects.64

In conclusion, evinacumab is highly effective in cardiovascular prevention for HoFH patients due to LDL cholesterol reduction. Additionally, its capacity to lower triglycerides should make it very useful in reducing the risk of acute pancreatitis. However, results from future clinical research are awaited. In this regard, zodarsiran, an siRNA targeting ANGPTL3 mRNA, demonstrated a 20% reduction in LDL cholesterol, 63% in triglycerides, and 22% in apoB at a 200 mg dose.

Lipoprotein(a)-lowering drugsLp(a) is a lipoprotein particle similar to LDL, bound via a disulfide bridge to apo(a), which carries cholesterol and oxidized phospholipids, exhibiting proinflammatory and prothrombotic properties. Evidence has confirmed that hyperlipoproteinemia(a) causes CVD, aortic valve stenosis, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality,65 adding additional risk for individuals with T2DM. Since Lp(a) levels are genetically determined and minimally influenced by environmental factors, measuring Lp(a) at least once in individuals with T2DM is recommended to individualize cardiovascular risk estimation. Three gene-silencing therapies targeting hepatic apo(a) production are under development. The most advanced is pelacarsen (antisense oligonucleotide), followed by olpasiran (siRNA) and zerlarsiran (siRNA). However, there is uncertainty about the potential risk of these new drugs increasing diabetes risk. While Mendelian randomization studies yielded conflicting results,66 studies in different populations have indicated an inverse relationship between Lp(a) levels and T2DM risk. Of note, this relationship is not linear across the entire range of Lp(a) concentrations, becoming evident primarily at very low Lp(a) levels and disappearing at medium or high concentrations.67–69 Clarifying this relationship is critical, as if confirmed, achieving very low Lp(a) concentrations could raise concerns about increasing T2DM risk. Epidemiological data suggest that reducing Lp(a) concentrations to extremely low levels would be necessary to increase diabetes risk, a scenario unlikely in clinical practice.66 On the other hand, excess Lp(a) undoubtedly predisposes diabetic individuals to micro- and macrovascular complications. Clinical trials with PCSK9 inhibitors suggest that in individuals with T2DM or prediabetes, the potential diabetogenic risk of lowering Lp(a) would be far outweighed by the cardiovascular benefit associated with a marked reduction in atherogenic cholesterol.70

Ongoing clinical studies with pelacarsen and olpasiran will provide relevant insights into the association between very low Lp(a) levels and T2D risk, as well as the drug impact on CVD and the risk-benefit relationship in treated individuals.

ConclusionsDespite advances made in recent decades, effective prevention remains a challenge in cardiovascular medicine. Regarding lipid disorders in T2DM, LDL cholesterol reduction is the primary endpoint, with combined therapy of statins and ezetimibe and/or PCSK9 modulators as the cornerstone. Beyond controlling LDL cholesterol levels, reversing the lipoprotein abnormalities responsible for residual cardiovascular risk is necessary: atherogenic dyslipidemia and hyperlipoproteinemia(a). Of the clinical trials aimed at reducing cardiovascular risk in individuals with or without T2DM and elevated triglyceride levels, only high-dose icosapent ethyl has shown cardiovascular benefits. New drugs in the pipeline to lower LDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, or Lp(a) promise to reduce cardiovascular risk, particularly in T2DM patients, or the risk of acute pancreatitis for triglyceride-lowering therapies. When evaluating these new drugs, their impact on carbohydrate metabolism and the risk of new-onset diabetes or glycemic control must also be considered.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAll authors contributed significantly to the work presented in this article, meet ICMJE (Committee of Medical Journal Editors) authorship criteria, and approved the publication of the article.

FundingNone declared.

Manuel Aguilar Diosdado (Hospital Puerta del Mar, Cádiz); Francisco J. Arrieta (Hospital U. Ramón y Cajal, Madrid); Antonio Becerra Fernández, Manuel Antonio Botana López (Hospital U. Lucus Augusti, Lugo); María del Mar Campos Pastor (Hospital U. Clínico San Cecilio, Granada); Santiago Durán García (Sevilla); José Antonio Fornos Pérez (Farmacia, Cangas de Morrazo); José Antonio Gimeno Orna (Hospital Clínico U. Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza); Olga González Albarrán (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Maran˜ón, Madrid); Montse Guardiola Guionnet (Universitat Rovira i Vigili, Reus); Gonzalo Fernando Maldonado Castro (Hospital U. de Álava, Vitoria); Carmela Teresa Manrique Mutiozábal (Hospital de Urduliz, Urduliz); Ana Belén Man˜as Martínez (Hospital Clínico U. Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza); José Ignacio Martínez Montoro (Hospital U. Virgen de la Victoria, Málaga); Inés Mera Gallego (Farmacia Eduardo Satue de Velasco, Maella); Laura Montá- nez Fernández (Hospital U. Ramón y Cajal, Madrid); Jorge Navarro Pérez (Hospital Clínico U. de Valencia, Valencia); Juan Carlos Obaya Rebollar (C.S. Chopera, Alcobendas); Emilio Carlos Ortega Martínez de Victoria (Hospital Clínico y Provincial de Barcelona, Barcelona); Ángel Michael Ortiz Zún˜iga (Hospital U. Valle de Hebrón, Barcelona); José Luis Pardo Franco (C.S. Orihuela I, Orihuela); Juan Pedro-Botet Montoya (Hospital del Mar, Barcelona); José Carlos Pérez Sánchez (C.S. Rincón de la victoria, Rincón de la Victoria); Antonio Pérez Pérez (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona); Carlos Puig Jové (Hospital U. Mutua de Tarrasa, Tarrasa); Josep Ribalta Vives (Universitat Rovira i Vigili, Reus); Víctor Sánchez Margalet (Hospital U. Virgen Maca- rena, Sevilla); Francisco Javier Tébar Massó (Murcia); Juan Manuel Zubiría Gortázar (Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra, Pamplona).