Approximately 200 million people have been diagnosed with thyroid disease worldwide. Associations between thyroid disorders and nutritional factors have been established in former studies.

MethodsThe Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus databases and Google Scholar were searched without date restriction until June 2023 by using relevant keywords. All original articles written in English that studied the effects of vitamin D supplementation on TSH and thyroid hormones were eligible for the present review.

ResultsThe present review included a total of 16 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 1127 participants (intervention group, 630; control group, 497). Based on the findings made, vitamin D supplementation had no significant effects on serum TSH levels in 9 cases (56.2%) reported in the trials. However, TSH levels were elevated in 4 studies (26.6%) and low in 3 (18.7%) cases after vitamin D administration. Four cases reported in 6 RCTs and 4 cases reported in 5 trials indicated no significant effects on thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) levels after vitamin D supplementation, respectively. Moreover, 8 cases of 11 included RCTs reported that vitamin D intake had no significant effects on fT4, and 5 cases of 7 RCTs demonstrated no significant effects on fT3 levels after vitamin D supplementation.

ConclusionMost findings suggest that vitamin D supplementation had no significant effects on thyroid hormones and more than half indicated no significant effect on TSH levels. Nevertheless, high-quality research is further required to prove these achievements and evaluate vitamin D effects on other markers of thyroid function.

Alrededor de 200 millones de personas han sido diagnosticadas con enfermedades tiroideas en todo el mundo. Estudios previos han establecido asociaciones entre los trastornos tiroideos y factores nutricionales. Esta revisión sistemática tiene como objetivo resumir los hallazgos sobre el efecto de la suplementación con vitamina D en la hormona estimulante de la tiroides (TSH) y otras hormonas tiroideas.

MétodosSe realizaron búsquedas en las bases de datos Web of Science, PubMed y Scopus y en Google Scholar sin restricción de fecha hasta junio de 2023 mediante palabras clave relevantes. Todos los artículos originales en inglés que evaluaron los efectos de la suplementación con vitamina D sobre la TSH y las hormonas tiroideas fueron elegibles para la presente revisión.

ResultadosEn esta revisión se incluyeron en total 16 ensayos controlados aleatorizados (ECA) con 1127 participantes (grupo de intervención: 630, grupo de control: 497). Según los hallazgos, la suplementación con vitamina D no tuvo efectos significativos sobre los niveles séricos de TSH en 9 casos (56,2%) de los ensayos. Sin embargo, los niveles de TSH aumentaron en 4 estudios (26,6%) y disminuyeron en 3 (18,7%) casos después de la administración de vitamina D. Cuatro casos de 6 ECA y 4 casos de 5 ensayos no indicaron efectos significativos sobre los niveles de tiroxina (T4) y triyodotironina (T3) después de la suplementación con vitamina D, respectivamente. Además, 8 casos de 11 ECA incluidos informaron que la ingesta de vitamina D no tuvo efectos significativos sobre la fT4, y 5 casos de 7 ECA no demostraron efectos significativos sobre los niveles de fT3 después de la suplementación con vitamina D.

ConclusiónLa mayoría de los hallazgos sugieren que la suplementación con vitamina D no tuvo efectos significativos sobre las hormonas tiroideas y más de la mitad no indicó ningún efecto significativo sobre los niveles de TSH. Sin embargo, se necesita más investigación de alta calidad para demostrar estos logros y también evaluar los efectos de la vitamina D sobre otros marcadores de la función tiroidea.

The thyroid gland is the first endocrine gland that produces and secretes the triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) hormones, which have prominent effects on human growth, development, and metabolism, including maintaining thermogenic and metabolic homeostasis, reducing body weight, and impacting muscle function.1,2 Growing evidence highlights the critical role played by thyroid hormones in the normal growth and function of the human body.3,4 Thyroid disease is an overall term that includes various conditions that affect the thyroid function, size, or structure, mainly including hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, autoimmune thyroid disease, thyroid nodules, and thyroid cancer.5 The associations between thyroid disorders and health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, oral disease, depression, and cancer, have already been established in former studies.4,6–9 It is estimated that approximately 200 million people are diagnosed with thyroid disease worldwide.10

Nutritional factors such as iodine, selenium, and iron are components that impact the thyroid function.11,12 Vitamin D is another nutrient that may affect thyroid function.11,12 Vitamin D (1,25OH2D3) – a crucial nutrient for maintaining health – belongs to the steroid nuclear hormone superfamily.13 Vitamin D targets several organs and has multiple purposes. The biological impacts of vitamin D can be categorized into two groups: group #1 involves calcium and phosphorus metabolism, which is regarded as its regular activity; group #2 refers to the non-classical or alternative pathway, which primarily influences immune function, inflammation, anti-oxidation, anti-fibrosis, and various other processes.14–16 Furthermore, it exhibits inhibitory effects on numerous types of cancer.17,18

Low serum vitamin D levels are reported in patients with hypothyroidism, autoimmune thyroid diseases, and Hashimoto's thyroiditis vs healthy subjects partially due to intestinal malabsorption and vitamin D inactivation. Furthermore, patients ≥40 years old with Graves’ disease had significantly lower serum levels of vitamin D.19,20 The impaired immune-endocrine interactions caused by environmental factors can damage the balance between the Th1 (T helper type 1) and Th2 (T helper type 2) immune responses in genetically predisposed individuals. Hashimoto's thyroiditis is characterized by an autoimmune reaction mediated by Th1 cells, which causes thyrocyte degeneration and hypothyroidism. Conversely, Graves’ disease is characterized by a hyperreactive Th2-mediated humoral response vs the thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor, which leads to the formation of stimulatory antibodies and hyperthyroidism.

Therefore, recent trials have investigated the effects of vitamin D supplementation on thyroid functions in several conditions reporting contradictory evidence.21–24 Considering this, this systematic review aimed to comprehensively summarize the findings made on the effect of vitamin D supplementation on TSH and thyroid hormones (T3 and T4) in different health conditions.

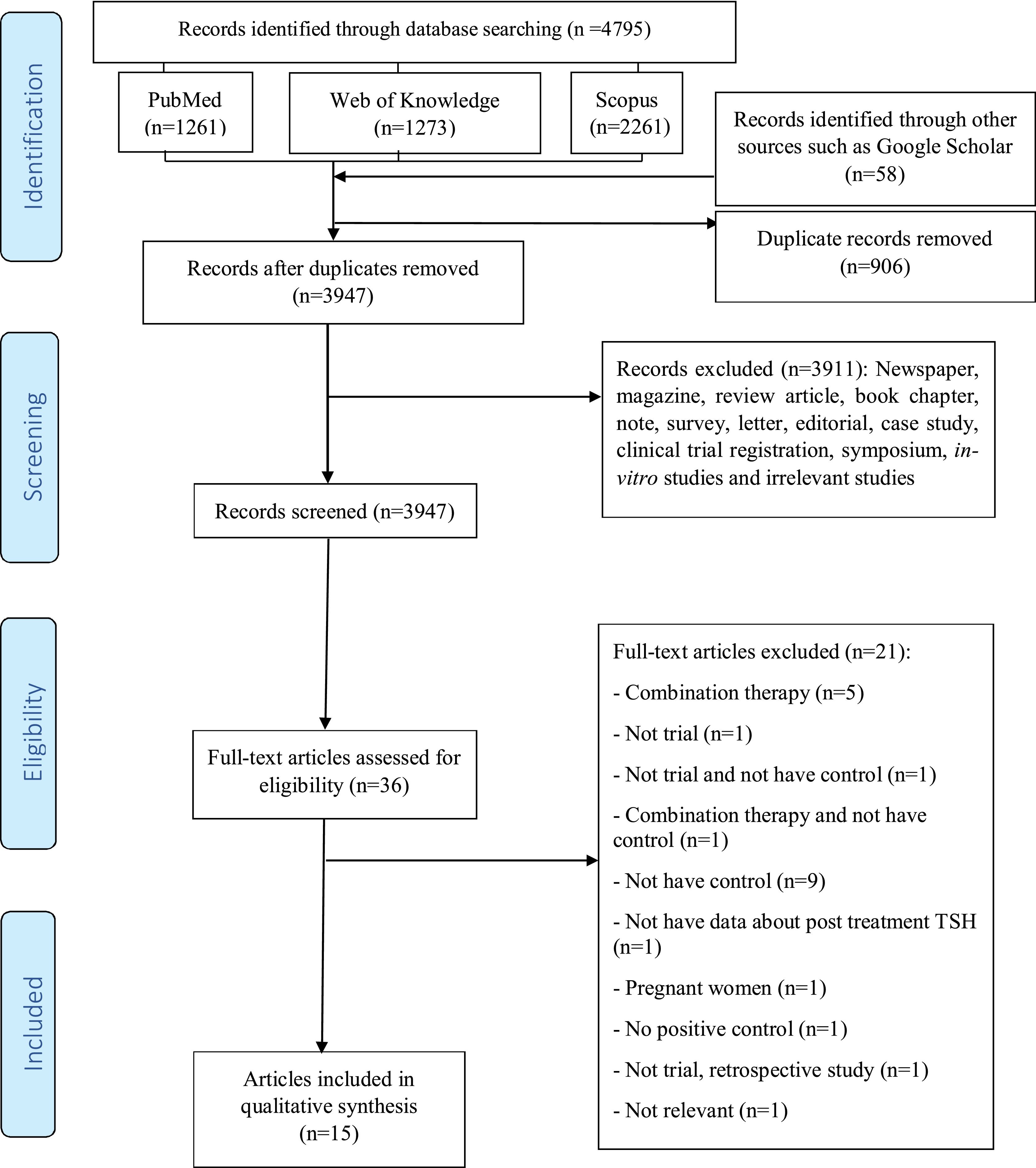

MethodsResearch strategyThe current systematic review followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) standards25 (Supplementary Table 1). PubMed, Scopus, Web of Knowledge, and Google Scholar were systematically and comprehensively searched until June 2023, using related keywords (PubMed search strategy is shown in Supplementary Table 2). Eventually, forward and backward citation tracking was performed on all the included research to make sure all qualifying papers would be included. Moreover, a manual search was conducted on Google.

Eligibility criteriaThe research questions and inclusion/exclusion criteria were structured according to PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparators, and Outcome) criteria (Table 1). All English-written original human studies assessing the impact of vitamin D supplementation on TSH and thyroid hormones were included in this review. Literature reviews, newspaper articles, magazine articles, conference abstracts, book chapters, notes, brief surveys, correspondence, editorials, case report studies, clinical trial registration were excluded. Studies on the effects of combining vitamin D and other drugs and nutraceuticals were also deemed ineligible.

PICOS criteria for inclusion of studies.

| Parameter | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Participants | All type of patients |

| Intervention/correlate | Vitamin D supplementation |

| Comparison | Placebo |

| Outcomes | Vitamin D effects on TSH, T4, and T3 |

| Study design | Randomized controlled trialsPublished in English up to June 2023 |

Following a database search, EndNote X8 was utilized to eliminate duplicate references. Subsequently, two independent reviewers assessed the titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles to identify eligible studies following the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Once unrelated studies were excluded, the eligibility of the remaining studies was determined by examining their complete texts. Inconsistencies between the two examiners were resolved through deliberation or by the opposing reviewer.

Data curationThe design of initial data mining form fully complied with the guidelines set forth in PRISMA and specific study designs. After pilot testing on two articles of each study type, the document underwent further refinement. Subsequently, data were drawn from all included studies by two independent reviewers. Curated data were the lead author's name, year of publication, study location, study population, number of participants in each group of the study, gender of participants, dose of vitamin D supplementation, duration of intervention, type of supplemented control, and findings made of the effects of vitamin D supplementation on TSH and thyroid hormones. The data mining sheet is summarized in Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies that examined the effects of vitamin D supplementation on TSH and thyroid hormones.

| First author | Baseline vitamin D | Year | Country | Subject | Male/female | Age | n/treatment group | n/control group | Treatment | Control | Duration of intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safari et al. | Not reported | 2023 | Iran | Subclinical hypothyroidism | Female | 20–65 | 22 | 22 | 10,000IU vitamin D/weekly | Sun flower | 3 months | ↓TSHfree and total T3free and total T4 |

| Grover et al. | Insufficiency | 2021 | India | Cirrhosis | 127 male/37 female | 18–60 | 57 | 67 | 60,000IU vitamin D (one capsule/week within the first 2 months, followed by 1 capsule/month for 10 months) | Sugar spheres | 12 months | TSHfT4 |

| Ebrahemi Rokni et al. | Deficiency, insufficiency | 2021 | Iran | Overweight males | Male | 45–55 | 13 | 13 | 50,000IU vitamin D/weekly | Paraffin | 8 weeks | ↓TSH |

| Mei et al. | Deficiency | 2021 | China | Hyperthyroidism (Graves’ disease) with hypercalcemia | 15 male/21 female | 18–70 | 18 | 18 | 800–1200IU vitamin D3/daily | Methimazole | 12 months | ↑TSH↓fT3↓fT4 |

| Krysiak et al. | Insufficiency | 2020 | Poland | Prediabetic women with Hashimoto's thyroiditis | Female | 25–50 | 16 | 15 | Metformin+4000IU vitamin D/daily | Metformin | 6 months | ↓TSHfree and total T3free and total T4 |

| Chahardoli et al. | Deficiency, insufficiency | 2019 | Iran | Hashimoto's thyroiditis | Female | 18–48 | 19 | 21 | 50,000IU vitamin D3/weekly | Paraffin | 3 months | TSH↔T3↔T4 |

| Talaei et al. | Deficiency, insufficiency | 2018 | Iran | Hypothyroid | Female | 20–60 | 102 | 99 | 50,000IU vitamin D/weekly | Paraffin | 3 months | ↓TSH↔T3↔T4 |

| Krysiak et al. | Deficiency | 2018 | Poland | Hashimoto's thyroiditis | Female | 25–50 | A:19B: 20 | 18 | A: 2000IU vitamin D/daily+40mg/daily simvastatinB: 2000IU vitamin D/daily | Simvastatin (40mg/daily) | 6 months | TSHfT3fT4 |

| Purnamasari et al. | Deficiency, insufficiency | 2017 | Indonesia | Graves’ disease | Not reported | 36±8.81 | 12 | 13 | Propylthiouracil+60IU alfacalcidol/daily | Propylthiouracil+placebo | 8 weeks | fT4TSH |

| Anaraki et al. | Deficiency | 2017 | Iran | Hashimoto's thyroiditis | 36 female/20 male | 43.81±1.57 | 30 | 26 | 50,000IU vitamin D/weekly | Placebo | 12 weeks | TSH |

| Knutsen et al. | Deficiency | 2017 | Norway | Healthy | 181 female/69 male | 18–50 | A: 84B: 85 | 82 | A: 1000IU vitamin D3/dailyB: 400IU vitamin D3/daily | Placebo | 16 weeks | TSHfT4 |

| Krysiak et al. | Normal | 2017 | Poland | Hashimoto's thyroiditis | Female | 20–50 | 16 | 18 | 2000IU vitamin D/daily | Levothyroxine | 6 months | TSHfT4fT3 |

| Krysiak et al. | Deficiency, insufficiency | 2016 | Poland | Postpartum thyroiditis | Female | 20–40 | A: 11B: 21 | 21 | A: 4000IU vitamin D/dailyB: 2000IU vitamin D/daily | Nothing | 3 months | TSHfT3fT4 |

| Simsek et al. | Deficiency | 2016 | Turkey | Autoimmune thyroid | 68 female/14 male | Intervention:35.8±12Control:39.7±12.6 | 46 | 36 | 1000IU vitamin D/daily | Nothing | 1 months | TSHfT4 |

| Kawakami-Tani et al. | Not reported | 1997 | Japan | Graves’ disease | 40 female/5 male | 16–67 | 15 | 15 | 60IU vitamin D3/daily+30mg/daily methimazole | 30mg/daily methimazole | 24 weeks | ↑TSH↓fT4↓fT3↓T3↓T4 |

| Barsony et al. | Deficiency | 1986 | Hungary | Hypothyroid patient | 36 female/1 male | 18–86 | A:12B:12 | 13 | A: A single dose of 100,000IU vitamin DB: A single dose of 100,000IU vitamin D+thyronine | Nothing | 6 months | ↓TSH↑T4 |

fT3: free triiodothyronine; fT4: free thyroxine; IU: international units; n: number; TSH: thyroid stimulating hormone; T4: thyroxine; T3: triiodothyronine.

Each qualified paper was evaluated for the potential risk of bias using the Cochrane Handbook,26 a tool to assess the risk of bias in RCTs. Two authors (SS, RM) independently evaluated the risk-of-bias criteria of all included studies. A third reviewer resolved discrepancies between these two. The Cochrane collaboration's tool has six bias domains with three response options of “low,” “unclear,” and “high” risk of bias. After responding to all items, each study included was deemed to have a “low risk of bias” when it had a low risk of bias for all three key domains, “unclear risk of bias” when it had the unclear risk of bias for ≥1 key domain, and “high risk of bias” when it had a high risk of bias for ≥1 key domain. Due to their importance, selection, performance, and detection bias were considered the key domains for judgment of the overall risk of bias.

ResultsStudy selectionFig. 1 illustrates the PRISMA flow diagram. Initially, a total of 4795 articles were retrieved after searching electronic databases, including Scopus (n=2261), Web of Knowledge (n=1273), and PubMed (n=1261). Moreover, a total of 58 articles were retrieved after searching in Google Scholar. After removing duplicates, the remaining 3947 articles were thoroughly screened by title and abstract. Among these, although a total of 37 articles were evaluated, 21 articles were removed because they studied the combination therapy (n=5), were not trials (n=1), were not trials and had no control groups (n=1), studied combination therapy and had no control groups (n=1), had no control groups (n=9), did not have any data on the post-treatment TSH situation of the patients (n=1), studied pregnant women (n=1), had no positive controls (n=1), were not trials and were retrospective studies (n=1), or were deemed irrelevant (n=1). A total of 16 clinical trial studies were finally included in the present systematic review. Table 2 provides an overview of the characteristics of the articles which finally made to our review.

Study characteristicsThe present systematic review included a total of 16 RCTs with 1127 participants, 630 of them in therapy groups. The mean age of participants was between 18 and 86 years old. The studies included were published from 1986 through 2023. The countries of origin of the studies included were Poland (4),27–30 Iran (5),31–35 India (1),36 China (19),37 Indonesia (1),23 Norway (1),38 Turkey (1),39 Japan (1),24 and Hungary (1).40 Seven cases of the studies included involved both genders of patients,24,34,36–40 7 cases studied only females,27–30,32,33,35 1 case only males,31 and 1 study did not mention the gender of participants.23 The individuals who participated in the trials were overweight men,31 had hyperthyroidism (Graves’ disease),23,24,37 were prediabetic women with Hashimoto's thyroiditis,27 had Hashimoto's thyroiditis,28,30,32,34 were patients with hypothyroidism,33,40 autoimmune thyroiditis,39 postpartum thyroiditis,29 cirrhotic patients,36 patients with subclinical hypothyroidism,35 and healthy subjects.38 The serum vitamin D levels of participants at the beginning of the study was insufficient or deficient in 5 trials,23,29,31–33 deficient in 6,28,34,37–40 insufficient in 2,27,36 and normal in 1,30 while 2 trials did not provide any information on the status of vitamin D of participants at the beginning of the study.24,35 The dose of vitamin D supplement was 60–4000IU/day in 9 trials,23,24,27–30,37–39 50,000IU/weekly in 5,31–35 60,000IU/weekly in 1,36 and a single dose of 100,000IU also in 1 trial.40 Control groups received methimazole, metformin, simvastatin, levothyroxine, methimazole, or placebo. In three RCTs, the treatment group received a combination of vitamin D supplement and metformin,27 propylthiouracil,23 and methimazole.24 The duration of vitamin D supplementation went from 1 up to 12 months.

Methodological qualityThe risk of bias assessment of the RCTs included is shown in Supplementary Table 3. Based on the Cochrane collaboration's criteria, 7 RCTs23,32–36,38 had a low risk of bias. However, 6 RCTs24,28,31,37,39,40 had unclear risk of bias and 3 RCTs27,29,30 a high risk of bias. Both the personnel and participants were not blinded in 3 RCTs27,29,30 while in 2,29,30 allocation concealment was not observed during patient allocation. Moreover, other RCTs did not report clear data on allocation concealment,27,28,40 blinding of personnel and participants,24,28,31,37,39,40 random sequence generation,28–30,40 or complete outcome data.23

Effects of vitamin D supplementation on thyroid hormonesAs shown in Table 2, the effect of vitamin D supplementation on TSH was studied in all of the trials included; in 9 RCTs (60%) vitamin D treatment did not influence the serum TSH levels, significantly. However, TSH levels increased in 4 RCTs (26.6%) and decreased in 2 (13.4%) after vitamin D administration. Five RCTs assessed the effects of vitamin D on T4 levels, 3 of which indicated no significant impact, 2 trial confirmed an increase, and the remaining one a decrease of T4 levels. Four RCTs reported data about T3, 3 of which showed that vitamin D supplementation did not have significant effects on T3 levels and 1 confirmed a decrease in T3 concentration. Moreover, 10 RCTs evaluated the effects of vitamin D intake on the fT4 levels, 7 of which reported no significant effects and 2 a decrease in the fT4 concentration. Regarding fT3, 4 out of 6 RCTs showed no significant effects and while the remaining 2 reported lower fT3 levels after vitamin D supplementation.

DiscussionIn the present study, we conducted systematic review on the available RCTs on the effects of vitamin D supplementation on thyroid hormones and TSH under various health conditions. Most trials found no significant effects of vitamin D on these hormones. These findings happen to be consistent with a former meta-analysis by Jiang et al. on the effects of vitamin D on Hashimoto's thyroiditis, who reported no significant changes in TSH, fT3, and fT4 levels vs control after vitamin D treatment.41 Nonetheless, these effects may be influenced by the baseline thyroid function, vitamin D levels, and use of drugs. In this context, it has been reported that hypovitaminosis D and hypocalcemia are associated with the severity of hypothyroidism, which could impact the size of the effects of vitamin D.42 Moreover, thyroid hormone levels may indirectly affect vitamin D status in patients with thyroid disease.43 However, due to the heterogeneity among the studies included, a meta-analysis could not be performed to better elucidate the overall effects.

Some of the trials included in this review reported beneficial effects of vitamin D supplementation on TSH levels under hypothyroid or hyperthyroid conditions.24,27,33,35,37 Similarly, another study found that vitamin D supplementation improved (decreased) TSH levels in patients with euthyroid autoimmune thyroiditis (hypothyroid condition) and severe hypovitaminosis D.44 Vitamin D levels are reported to be inversely correlated with TSH levels and positively correlated with thyroid hormones in patients with hypothyroidism.45 The function of vitamin D on gene expression occurs through binding to the nuclear vitamin D receptor (VDR), which is present in almost all organs of the human body. Vitamin D receptors have been reported to be present in rat thyrotropes in the pituitary gland, which could influence TSH secretion.46 The structural similarities between VDR and TSH receptors suggest that vitamin D regulates pituitary TSH secretion by binding to specific sites on the receptors. Additionally, vitamin D can directly impact thyrocytes by reducing the absorption of iodide stimulated by thyrotropin and inhabiting cell growth.20,47

VDR gene polymorphism – which alters vitamin D functions – is associated with a higher risk of Hashimoto's thyroiditis and Graves’ disease.48,49 Furthermore, of note that vitamin D substantially increases serum calcium and phosphorus concentrations, while hypercalcemia suppresses TSH and thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) production.19 Lamberg-Allardt et al. indicated that vitamin D suppresses TSH-stimulated iodide absorption in a dose-dependent manner, indicating that 1,25(OH)2D3 influenced the physiological function of thyroid follicular cells in rats.21

Vitamin D could also exert its beneficial effects on autoimmune thyroid diseases via its anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects and by reducing autoantibody titers.30,37,44,50 Low levels of serum 1,25(OH)2D3 are correlated with increased synthesis of anti-thyroid peroxidase (TPOAb) and anti-thyroglobulin (TgAb).51 Vitamin D modulates the differentiation and activation of CD4+ T lymphocytes, thereby inhibiting autoimmune responses. Furthermore, vitamin D exerts immunosuppressive effects on dendritic cells,52 downregulates antigen-presenting cells, and decreases cytokine production.44 1,25(OH)2D inhibits the antigens surface expression in immune system cells while suppressing the differentiation, maturation, activation, and survival of these cells, causing decreased antigen presentation and T cell activation. Moreover, 1,25(OH)2D also modulates DC-derived cytokine expression by inhibiting the production of interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23 and enhancing the release of IL-10. Thereby, 1,25(OH)2D indirectly shifts the T cell polarization from Th1 and Th17 phenotypes towards the Th2 phenotype.53,54 In addition, 1,25(OH)2D inhibits the proliferation and differentiation of B cells into plasma cells, memory B cell generation, immunoglobulin secretion (IgG and IgM) and induces B cell apoptosis.54–56 The 1,25(OH)2D ability to suppress the adaptive immune system leads to the promotion of immune tolerance and is beneficial for many autoimmune diseases.56,57

Due to the immunosuppressant effect, some studies suggest vitamin D supplementation in patients with elevated antibody titers even with normal vitamin D levels. Vitamin D supplementation has also shown a favorable effect on thyroid volume and the degree of exophthalmos in patients with Graves’ disease.58 However, more research is needed in this area.

The present study encountered several limitations. Firstly, the heterogeneity among the studies included precluded the possibility of conducting a meta-analysis and presenting definitive outcomes. Secondly, most studies included exhibited either a high or uncertain risk of bias. Thirdly, variations in geographic region, dosage, type, and duration of vitamin D supplementation, baseline severity of vitamin D deficiency, clinical severity of each disease, and overall health conditions across studies hindered the ability to reach conclusive inferences. To address these limitations, well-designed randomized controlled trials are warranted to elucidate the precise effects of vitamin D supplementation in various patient cohorts with thyroid diseases.

In conclusion, the RCTs included in the present systematic review revealed mixed results regarding vitamin D effects on TSH and thyroid hormones while most of them suggested that vitamin D supplementation had no significant effects on thyroid hormones. Moreover, more than half reported no significant effect on TSH levels. Therefore, high-quality research is further required to clarify the effects of vitamin D supplementation on TSH and thyroid hormones and evaluate the effects of vitamin D on other markers of the thyroid function.

Ethical approvalThe protocol of the current study was approved by the Ethic Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran (ethical code: IR.TBZMED.VCR.REC.1402.273).

FundingThe research protocol was approved and supported by the Research Vice-Chancellor and Nutrition Research Center of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran (grant number: 73212).

Conflicts of interestNone declared.