To evaluate the effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) on the risk of major adverse limb events (MALE).

MethodsWe conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials assessing the effects of GLP-1RAs therapy on peripheral arterial disease (PAD)-related outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). This meta-analysis was performed according to PRISMA guidelines. The random-effects model was performed.

ResultsA total of 6 randomized clinical trials were considered eligible for this systematic review. On the other hand, 4 clinical trials were included for the meta-analysis. A total of 15,427 subjects were allocated to the GLP-1RAs group, and 15,476 to the placebo group. Overall, this meta-analysis showed that the use of GLP-1RAs is associated with a lower risk of PAD-related events (OR, 0.78; 95%CI, 0.62–0.98, I2=39%) vs the placebo group. The analytical evaluation did not suggest publication bias, and the sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the result was robust.

ConclusionThis meta-analysis demonstrated that the use of GLP-1RAs is associated with fewer PAD-related clinical events. Of note, despite the clinical significance of PAD, most analyzed studies did not specifically report on these events. Future studies should include PAD as a key endpoint. PROSPERO Registration: CRD42024565567.

Evaluar el efecto de los agonistas del receptor del péptido similar al glucagon tipo 1 (AR-GLP-1) sobre el riesgo de eventos adversos mayores en las extremidades.

MétodosRealizamos una revisión sistemática y un metaanálisis de ensayos clínicos aleatorizados que evaluaron los efectos de la terapia con AR-GLP-1 en los eventos clínicos relacionados con la enfermedad arterial periférica (EAP) en los pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (DM2). Este metaanálisis se llevó a cabo de acuerdo con las directrices PRISMA. En el análisis estadístico se utilizó un modelo de efectos aleatorios.

ResultadosSe consideraron elegibles para esta revisión sistemática 6 ensayos clínicos aleatorizados. Por otro lado, se incluyeron 4 ensayos clínicos para el metaanálisis. Un total de 15.427 sujetos fueron asignados al grupo bajo tratamiento con AR-GLP-1 y 15.476 individuos, al grupo placebo. Este metaanálisis evidenció que el uso de AR-GLP-1 se asocia con un menor riesgo de eventos adversos mayores en las extremidades (OR: 0,78; IC del 95%: 0,62 a 0,98, I2=39%) en comparación con placebo. La evaluación analítica no sugirió sesgo de publicación y el análisis de sensibilidad demostró que el resultado fue sólido.

ConclusiónEl uso de AR-GLP-1 se asoció con una reducción de los eventos clínicos relacionados con la EAP. Es de destacar que, a pesar de la importancia clínica de la EAP, la mayoría de los estudios analizados no informaron específicamente sobre estos eventos. Los estudios futuros deberían incluir la EAP como criterio de valoración clave. Registro en PRÓSPERO: CRD42024565567.

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is a clinical manifestation of atherosclerotic disease, typically affecting the abdominal aorta, iliac arteries, and lower limbs.1 This condition is associated with a higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and major adverse limb events (MALE), and is a strong predictor of both all-cause and cardiovascular mortalities.2 Additionally, hospitalizations due to PAD have led to a substantial economic burden on health care systems.3

In addition to their glucose-lowering effects, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) are associated with weight loss and have multiple favorable metabolic and anti-inflammatory effects.4 Due to their cardio- and nephro-protective properties, GLP-1RAs are recommended as first-line antidiabetic therapies for patients at high cardiovascular risk.5 Moreover, GLP-1RAs may improve arterial stiffness and provide systemic microcirculatory benefits in the peripheral vascular system. Activation of GLP-1 receptors in peripheral vessels could potentially stimulate arterial wall remodeling, leading to reduced intima-media thickness and enhanced stability of atherosclerotic plaques.6

However, while the association between the use of these drugs and a lower incidence of coronary or cerebrovascular disease is well established,7 their impact on PAD-related events remains poorly understood. One contributing factor is that many studies evaluating treatments for cardiovascular prevention typically focus on common cardiovascular events such as coronary heart disease or stroke, often overlooking the reporting of MALE. This is highlighted by the strong (Class I) recommendations in current clinical practice guidelines,8 which indicate that for patients with PAD and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), GLP-1RAs effectively reduce the risk of MACE. However, these guidelines do not specify the effect on MALE. There is only one Class IIb recommendation suggesting that glycemic control may be beneficial in improving limb outcomes for patients with PAD and T2DM.

A previously published narrative review analyzed the available evidence on this topic.9 However, this study included observational studies and did not consider the latest clinical trials published to this date.

Based on the considerations mentioned earlier, the main objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review and an updated meta-analysis on the effect of GLP-1RAs on PAD-related events.

Material and methodsData extraction and quality assessmentThis study was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) on the reporting of systematic reviews.10 This systematic review was recorded in PROSPERO.

We conducted a literature search identifying clinical trials on GLP-1RAs published until May 31st, 2024. Two independent reviewers searched across the electronic PubMed/MEDLINE, Scielo, Embase and Lilacs databases using the either the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms or keywords “efpeglenatide”, “liraglutide”, “dulaglutide”, “albiglutide”, “exenatide”, “lixisenatide”, “semaglutide”, and “GLP-1RAs”, combined with “peripheral arterial disease”, “amputation”, “peripheral revascularization” or “major adverse limb events”, and data were extracted. In addition, the authors also searched for ‘snowball’ to find other articles of interest. To match each individual descriptor and define the search, we used the Boolean operator “AND”. Only studies conducted in humans were included. No language restrictions were used in the search.

The following inclusion criteria were established: (a) Studies comparing the impact of GLP-1RAs on PAD-related events with either a placebo or a control group; (b) Studies with a minimum follow-up≥6 months; (c) Randomized clinical trials.

The primary endpoint of this meta-analysis was the occurrence of MALE. The PAD-related events identified in this review were those established by the original articles.

Potential risks of bias were assessed for all studies using tools specifically developed for this purpose, such as the RoB 2 (revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials).11 This tool assesses bias on 5 different domains: bias from randomization, bias due to deviations from planned intervention, bias due to lack of outcome data, bias of outcome measurement, and selection bias of reported outcome. Each domain was rated as “high risk”, “low risk” or “with some concerns”, further obtaining an overall rating of each study. Two authors determined the risk of bias for each article. Disagreements were resolved with a third reviewer.

Statistical analysisThe summary effect of GLP-1RAs on the endpoint of MALE was estimated. Measures of effect size were expressed as odds ratios (ORs), and the I2 statistic was calculated to quantify between trial heterogeneity and inconsistency. A random-effects model was chosen because the trials differ in the populations included or in the follow-up. To compare the mean effect across subgroups, we used a Z-test. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05 (2-tail analysis). Statistical software R (version 3.5.1) was used for the analysis.12 The sensitivity analysis consists of replicating the results of the meta-analysis, excluding at each step, each of the studies included in the review. If the results obtained are similar, both in the direction/size of the effect and in statistical significance, the analysis indicates that the result is robust.

Analysis of publication biasDue to the limited number of studies, it was deemed inappropriate to construct a funnel plot using the standard error (SE) by log odds ratio (OR) to assess publication bias. Instead, an Egger's regression intercept test was conducted.

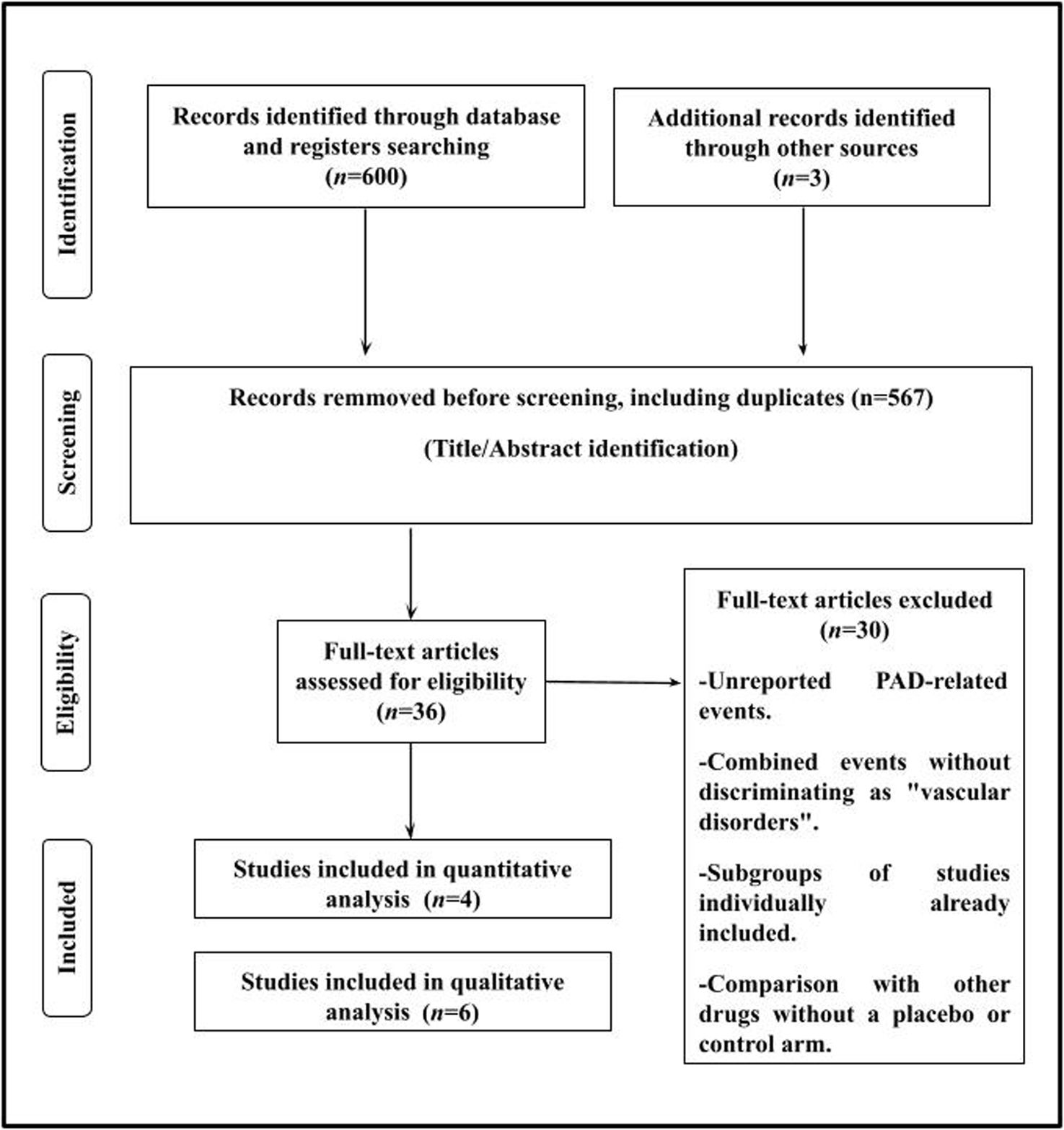

ResultsThe search included a total of 603 potentially relevant articles after examining the titles/summary, excluding 567 studies that were duplicate publications or which did not evaluate the purpose of this study. Subsequently, a thorough examination of the remaining articles led to the removal of 30 studies where the exposure/event of interest was not reported. A flowchart of the trial selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

This study consisted of 2 parts. Part #1 included conducting a qualitative analysis—systematic review—where all PAD-events were analyzed. Part #2 included performing a quantitative analysis—meta-analysis—where only studies reporting well-established PAD-related clinical events, such as amputation, peripheral arterial revascularization, or combined MALE, were included.

A total of 6 randomized clinical trials13–18 were identified and considered eligible for this systematic review. Studies that reported only “vascular disorders” or “vascular adverse events” as combined adverse effects without distinction were not analyzed.19–24 These events included hypo- and hypertension, and thrombotic, ischemic or hemorrhagic vascular episodes in any territory. On the other hand, a total of 4 clinical trials were included for the meta-analysis.13–15,18 A total of 15,427 subjects were allocated to the GLP-1RAs group and 15,476 individuals to the control or placebo groups. The SUSTAIN-916 study was excluded from the quantitative analysis because its definition of “adverse events potentially leading to lower limb amputation” included a broad range of heterogeneous clinical situations, including diabetic neuropathy, hypoesthesia, occlusive peripheral arterial disease, osteonecrosis, paresthesia, and peripheral neuropathy. Additionally, the STARDUST17 study was excluded because it did not report on any traditional clinical events. Instead, the study focused on reporting on peripheral perfusion measured by transcutaneous peripheral oxygen pressure (TcPO2) and results from the 6-min walk test.

The quality of the selected studies is shown in Fig. 2.

All patients included in the studies had T2DM. One study included patients with T2DM and chronic kidney disease,18 while another included patients with T2DM and PAD.17 Regarding the GLP-1RAs used, 3 studies administered semaglutide13,16,18; 2, liraglutide15,17; and 1, exenatide.14 The mean follow-up ranged from 24 up to 197.6 weeks. The characteristics of the studies included in this review are shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study (year) | n | PAD endpoint analyzed | GLP-1RA used | Population | Follow-up (weeks) | Main PAD result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUSTAIN-6 (2016)13 | 3297 | Peripheral revascularization. | Semaglutide 0.5/1mg sc weekly | Patients≥50 years of age with T2DM and established CVD or CKD, or ≥60 years of age and cardiovascular risk factors only. Mean age 64.6 years, male 60.7%, median BMI 32.8kg/m2. | 109.2 | Incidence rate per 100 patient/year: GLP-1RA: 0.47Placebo: 0.74p=0.16 |

| EXSCEL (2017)14 | 14,733 | Peripheral revascularization and non-traumatic amputation. | Exenatide 2mg sc weekly | Patients≥18 years of age with T2DM. Mean age 62 years, male 62%. History of PAD 19%. | 166.4 | Combined outcome265 vs 284 eventsp value not reported |

| LEADER (2018)15 | 9340 | Peripheral revascularization and amputation. | Liraglutide 1.8mg sc once-day | Patients≥50 years of age with T2DM and established CVD or CKD, or ≥60 years of age with, at least 1 cardiovascular risk factor. Mean age, 64.3 years; male, 64.3%; median BMI, 32.5kg/m2 | 197.6 | AmputationHR, 0.65 (0.45, 0.95) p=0.03Peripheral revascularizationHR. 0.87 (0.48, 1.58) p=0.64 |

| SUSTAIN-9 (2019)16 | 302 | Adverse events potentially leading to lower limb amputationa. | Semaglutide1mg sc weekly | Patients≥18 years of age with T2DM. Mean age, 57.0 years; male, 58.3%; mean BMI, 31.1kg/m2. | 30 | Event rate per 100 patient year:GLP-1RA; 7.6Placebo: 3.1p value not reported |

| STARDUST (2024)17 | 55 | Increase of at least 10% from baseline in TcPo2.6-minute walking distance. | Liraglutide 1.8mg sc once-day | Individuals 35 years or older with T2DM and a diagnosis of PAD. Mean age, 67.5 years; male, 78%; mean BMI, 31.1kg/m2. | 24 | Increase of at least 10% from baseline in TcPo2:RR, 1.91 (1.26–2.90) p<0.0016-min walking distance (meters)364.0 vs. 340.1p<.001 |

| FLOW (2024)18 | 3533 | Major adverse limb events:-Acute limb ischemia hospitalization-Chronic limb ischemia hospitalization | Semaglutide1mg sc weekly | Patients≥18 years of age with T2DM and established CKD. Mean age, 66.6 years; male 69.7%; median BMI 32kg/m2 | 176.8 | 16 vs 28 events.HR, 0.56 (0.30, 1.02)p value not reported |

BMI: body mass index; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CVD: cardiovascular disease; GLP-1RA: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; PAD: peripheral arterial disease; SC: subcutaneous; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; TcP02: peripheral transcutaneous oxygen pressure.

Overall, this meta-analysis shows that the use of GLP-1RAs is associated with a decreased risk of PAD-related events (OR, 0.78; 95%CI, 0.62–0.98, I2=39%) vs placebo groups (Fig. 3A).

The analytical evaluation does not suggest publication bias (Egger's regression intercept test: p=0.1063).

Sensitivity analysis shows that the primary finding is robust, with the overall results maintaining consistent directionality and magnitude even when each study is individually excluded (Fig. 3B).

DiscussionIn this study, we reviewed evidence from randomized clinical trials on the impact of GLP-1RAs on the risk of PAD-related events. Our meta-analysis suggests that GLP-1RAs confer a beneficial effect in reducing MALE risk.

Individuals with T2DM are at a high risk of developing atherosclerosis, with PAD representing the clinical presentation associated with the poorest prognosis vs the involvement of other vascular territories.25 Unlike non-diabetic individuals, those with T2DM show more severe clinical signs, partly due to concurrent neuropathy and a predominantly distal distribution of PAD, thereby increasing the risk of complications.26,27

A recently published meta-analysis by Ashraf et al. evaluated the efficacy profile of GLP-1RAs in reducing the risk of MACE in patients with T2DM and PAD included in the randomized clinical trials analyzed. This study identified a prevalence of PAD from 13% up to 25%, underscoring the heterogeneity in the definition of this disease and even in the related outcomes, such as MALE. Most included studies defined PAD based on prior revascularization, history of amputation, or symptoms consistent with intermittent claudication confirmed by an abnormal ABI (ankle-brachial index).28 However, this definition is overly insufficient, especially when considering criteria such as ABI, toe-brachial index (TBI), or Doppler waveform analysis. As a result, the available high-quality evidence to guide the routine medical practice in this clinical context is notably scarce vs the more substantial evidence base for conditions such as coronary artery disease.8

In line with this paradoxical issue in medicine, real-world data reveal that PAD is frequently underdiagnosed and undertreated. Evidence indicates a significant gap in the recognition of PAD in the routine clinical practice, inevitably leading to suboptimal management. For instance, the PARTNERS study demonstrated that only 49% of physicians managing patients with PAD were aware of the diagnosis.29 Secondly, regarding secondary prevention measures, it has been observed that patients with coronary or cerebrovascular disease achieve better control of their risk factors vs those with PAD. This disparity was evidenced by the REACH registry, which included more than 68,000 individuals.30 Thirdly, patients with PAD are less frequently managed by cardiologists, with their follow-up predominantly overseen by cardiovascular surgeons and interventionalists. This is significant because cardiologists are generally more rigorous in controlling risk factors.31

There is strong evidence supporting the cardiovascular benefits, including the reduction of MACE, associated with antidiabetic drugs such as sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors and GLP-1RAs. This evidence has precipitated a paradigm shift in the management of T2DM away from sole reliance on glycated hemoglobin levels. However, current societal guidelines do not provide individual recommendations specifically aimed at patients with concomitant PAD and T2DM.32 In this regard, there is a paucity of evidence regarding the effects of these drugs in patients with PAD, including their impact on MALE. However, GLP-1RAs exhibit substantial potential in treating PAD among patients with T2DM due to their systemic microcirculatory benefits in the peripheral vascular location. These benefits include attenuated inflammation and oxidative stress, enhanced endothelial function, vasodilation, and anti-atherosclerotic effects.6,33 Additionally, in one of the studies included in this systematic review of 55 patients with T2DM and PAD, the use of liraglutide improved peripheral perfusion, suggesting its potential to mitigate the clinical progression of PAD.17 In addition, the STRIDE trial (NCT04560998) is an ongoing study specifically designed to evaluate the impact of semaglutide on exercise capacity in patients with T2DM and intermittent claudication. This trial compares the effects of semaglutide vs placebo aiming to assess changes in maximum walking distance after 52 weeks of treatment, using a constant-load treadmill test.

Of note, most trials assessing the cardiovascular effects of GLP-1RAs did not prioritize PAD or lower limb vascular complications as primary or secondary endpoints. As far as we know, this meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials represents the first comprehensive synthesis on the impact of GLP-1RAs on PAD-related events risk. Therefore, our study revealed a 22% reduction in MALE risk among patients treated with GLP-1RAs vs those on placebo. While the definition of MALE is heterogeneous—events such as peripheral arterial revascularization and amputation are generally included within this definition; however, clinical situations such as hospitalizations for diabetic foot infection when revascularization is not required, or simply ulcers in patients with PAD managed outpatiently, are not considered in the definition of MALE—our analysis primarily focused on lower limb amputation and adverse events potentially leading to amputation as the main events. This finding is highly relevant because amputations entail negative impacts on the health of our patients, such as disability and loss of autonomy, and on the health care system due to associated high costs.34 Thus, GLP-1RAs could be considered as part of the optimal medical therapy for patients with T2DM and PAD to reduce the risk of PAD-related events.

The sensitivity analysis performed in our study yielded significant findings, wherein the exclusion of the EXSCEL trial14—utilizing exenatide—resulted in an enhanced protective effect of the remaining 3 studies, employing liraglutide15 and semaglutide,13,18 on MALE risk. These results are consistent with the absence of observed differences in MACE risk associated with exenatide in the EXSCEL trial,14 contrasting with the beneficial outcomes seen with liraglutide and semaglutide. This discrepancy highlights the need for studies specifically designed to assess the impact of GLP-1RAs on PAD-related events and determine whether all drugs within this class confer equivalent protection vs MALE risk.

The size of the beneficial effect observed in our study with GLP-1RAs on MALE is comparable to that reported for drugs widely accepted in the medical community for treating patients with PAD. In this context, a meta-analysis published by Masson et al. revealed that lipid-lowering therapy was associated with a 24% reduction in the risk of MALE in patients with PAD.35

Similar findings to those of our meta-analysis were observed in observational studies. Baviera et al. conducted a cohort study including large and unselected populations with T2DM in Lombardy and Apulia (Italy) to evaluate the safety and efficacy profile of GLP-1RAs and SGLT-2 inhibitors vs other glucose-lowering drugs.36 The authors demonstrated a significant reduction in hospitalizations for PAD and lower limb complications in both cohorts on GLP-1RAs vs other antidiabetic agents.

In a recent meta-analysis of 12 observational studies of patients with T2DM treated with either SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP-1RAs, the GLP-1RA group exhibited a significantly lower relative risk of lower limb amputation vs the SGLT2 inhibitor cohort (3.54 vs 4.72 events per 1000 patient-years).37 Furthermore, in the CANVAS program involving 10,142 patients with T2DM at high cardiovascular risk, canagliflozin was found to be associated with a 1.97-fold increased risk of lower-limb amputations. Independent predictors of amputation identified in the study included prior amputations, male sex, non-Asian ethnicity, history of PAD, history of neuropathy, albuminuria, and elevated HbA1c levels at baseline.38 While this finding was not replicated in other randomized clinical trials on SGLT-2 inhibitors, it is recommended to conduct a thorough screening for risk factors for amputations when initiating SGLT2 inhibitors. In patients with diabetic foot ulcers, it may be beneficial to initiate treatment with a GLP-1RA before considering an SGLT-2 inhibitor, delaying the latter until the wound has epithelialized.

This study emphasizes the importance of systematically including MALE as endpoints when assessing the safety and efficacy profile of drugs with cardiovascular effects. To validate our the findings of our study, it will be essential to gather more comprehensive data in the future, ensuring that the designs of upcoming clinical trials routinely incorporate MALE as endpoints.

This meta-analysis has several limitations. First, this meta-analysis incorporated a limited number of studies, compounded by the fact that these studies were not primarily designed to assess PAD-related events. Second, there was clinical heterogeneity due to the different characteristics of the populations, different GLP-1RAs used, and the different follow-up times. Therefore, despite the low risk of bias in the studies included the heterogeneity of clinical conditions among the different studies—such as impaired kidney function in the FLOW trial18 and the lack of significant cardiovascular protection observed in the EXSCEL trial14—may interfere with the interpretation of results. In addition, heterogeneity on the duration of T2DM, the prior history of atherosclerotic disease, and the specific treatment for PAD in patients with involvement of this vascular territory could significantly impact the assessed risk of MALE. Thirdly, sensitivity analysis indicated some coherence regarding the magnitude and directionality of the main finding, although in certain individual cases, confidence interval exceeded unity. We admit that this could be attributed to chance, given the limited number of studies analyzed and, consequently, the small number of events included. Finally, although the definition of the outcome was similar across the different studies included in the quantitative analysis, it was not exactly the same. Nevertheless, the events assessed were generally significant clinical issues.

ConclusionsThis meta-analysis—which included all current evidence—shows that the use of GLP-1RAs is associated with a decrease in PAD-related clinical events in patients with T2DM. Of note, despite the clinical significance of PAD, most studies analyzed did not specifically report on these events. Future studies evaluating drugs for cardiovascular prevention should include PAD as a key endpoint.

Authors’ contributionsWM and FG were involved in the conception and design of the research. WM, FG and LB participated in data collection. The interpretation of the data and the statistical analysis was conducted by ML. FG, WM while LB drafted the manuscript. All authors conducted a critical review of the final document. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Ethical approvalThis article is based on previously conducted studies and does not include any studies with human participants or animals conducted by any of the authors.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestWM and ML served as speakers from Novo Nordisk. The remaining authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

Availability of data and materialThe data underlying this article are available in the article.