Dementia is an increasingly prevalent disease in our environment, with significant health and social repercussions. Despite the available scientific evidence, there is still controversy regarding the use of enteral tube nutrition in people with advanced dementia. This document aims to reflect on the key aspects of advanced dementia, tube nutritional therapy and related ethical considerations, as well as to respond to several frequent questions that arise in our daily clinical practice.

La demencia es una enfermedad cada vez más prevalente en nuestro entorno, con importantes repercusiones sanitarias y sociales. Pese a la evidencia científica disponible, aún existe controversia sobre el empleo de la nutrición enteral por sonda en las personas con demencia avanzada. En el presente documento se pretende reflexionar sobre los aspectos clave de la demencia avanzada, el tratamiento nutricional por sonda y las consideraciones éticas relacionadas, así como dar respuesta a una serie de cuestiones frecuentes que se nos plantean en nuestra práctica clínica diaria.

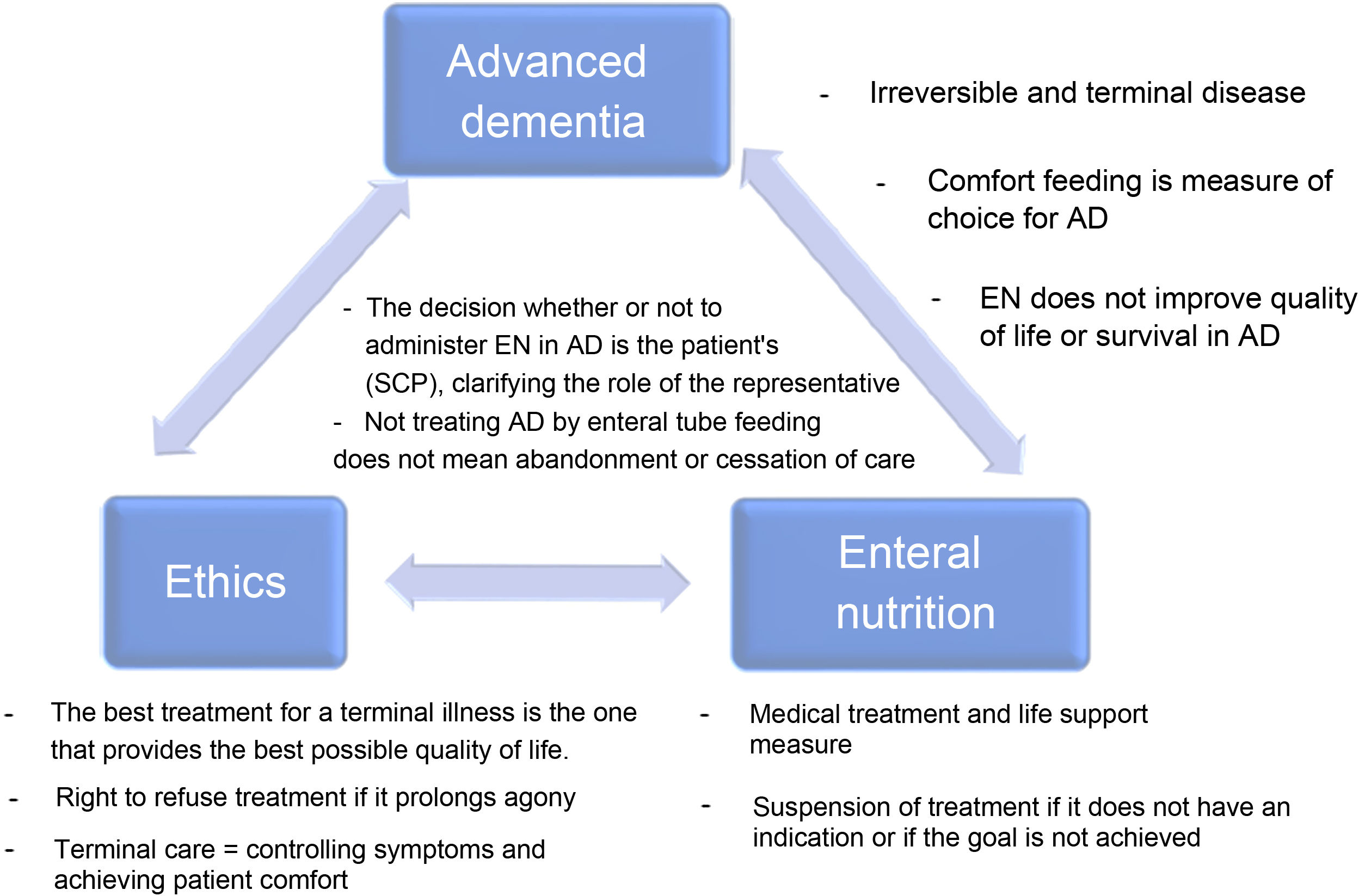

Dementia is an increasing prevalent disease in Spanish society, with significant health and social repercussions. Despite current scientific evidence, the use of enteral tube feeding in patients with advanced dementia (AD) remains subject to much debate. The aim of this document is to consider the key aspects of AD, the use of nutritional therapy by tube in advanced dementia patients and the associated ethical considerations (the main or strong ideas are detailed in Fig. 1), as well as to answer a series of frequently-asked questions that arise in our daily clinical practice.

DementiaDementia, or major neurocognitive disorder, is an incurable and progressive disease that causes severe impairment of cognitive, verbal and functional capabilities and affects daily life.1

The clinical course of dementia is not the same for all patients. Median survival after the onset of symptoms ranges from three to 12 years, and between three and 6.6 years following diagnosis, with the majority of this time spent in the more advanced stages of the disease.2 AD corresponds to stage 7 of the Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) and is characterised by the end stage of the disease with severe cognitive decline, major memory deficits such as the ability to recognise family members, minimal verbal abilities, inability to walk independently, dependency for all activities of daily living and urinary and faecal incontinence.3 The estimated survival in late-stage AD is less than six months for most patients.1 As such, AD is an irreversible and terminal disease.

A very common set of complications associated with AD arises from feeding difficulties, which are part of the natural progression of the disease. These include oral dysphagia (such as keeping the bolus in the mouth without swallowing), pharyngeal dysphagia (causing aspiration), swallowing apraxia, the inability to feed oneself and refusal to eat.1 The possibility of one of these complications being caused by an acute problem (infection, medications, etc.), which could be potentially reversible, should always be evaluated. If this is not the case, there are two main options: to maintain assisted oral feeding (comfort feeding) or to place an enteral feeding tube.4

Enteral nutritionMedical nutrition therapy includes routes for oral, enteral and parenteral artificial feeding. Rather than just the basic provision of food and liquids, artificial hydration and nutrition are medical treatment and life support measures. Initiating treatment with artificial nutrition or hydration alone requires an indication for that medical treatment, a definition of the therapeutic goal to be achieved and the will or informed consent of the patient or their legal representatives. In all cases, however, the treating physician has to take responsibility5 for the final decision that has been taken jointly. Like any medical treatment, artificial hydration and nutrition are not exempt from the risk of complications and are an invasive procedures.6

EN is a medical treatment7 that is usually administered by tube. This can be placed through the nose, such as a nasogastric (NG) or nasojejunal tube, or through a stoma (gastrostomy or jejunostomy), and the EN formula infused into the stomach or jejunum. EN has many advantages as a medical treatment but is not free of complications. In Spain, treatment with home EN is regulated by a legal framework, Spanish Royal Decree 1030/2006 of 15 September,8 which establishes the Spanish National Health System’s portfolio of common services and its updating procedure, as well as Annex VII of the above Royal Decree, which stipulates the portfolio of common provision services with dietary products. The prerequisites to access home EN are detailed in point 5 of Annex VII and require compliance with all the following points:

- a)

The patient’s nutritional needs cannot be met by regular food intake.

- b)

The administration of these products must lead to improved patient quality of life or potential recovery from a life-threatening condition.

- c)

The indication must be based on medical rather than social criteria.

- d)

The benefits must outweigh the risks.

- e)

The treatment must be periodically reviewed.

The goals of enteral nutrition therapy through a tube in a person with AD should be: to reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia, to improve nutritional status, functional status and quality of life, to reduce the risk of developing pressure ulcers and to increase survival. According to scientific evidence, EN does not achieve these goals in people with AD.9 In fact, some of these, such as the prevention of pressure ulcers, even seem to worsen with gastrostomy placement,10 not to mention the limitations it imposes on social interactions due to not being able to partake in the social act of eating, the loss of pleasure of tasting food and the risk of the feeding tube falling out, with its possible associated damage or the need for mechanical restraint.6 Given that enteral tube feeding improves neither the quality of life nor the survival of people with AD, oral comfort feeding is recommended to avoid these complications and achieve similar outcomes in terms of mortality, aspiration pneumonia, functional status and comfort as with EN.11

Ethical considerationsDeciding whether or not to initiate enteral tube feeding in patients with AD gives rise to a contentious situation, which can be understood with the following reflections.

Temporality and symbolismA difficulty inherent to these situations pertains to the stage of the patient’s disease when the decision is made. The individual variability of this phase of the process is problematic. It may be that the timing of when to introduce EN can only be perfected when the patient is facing their final days or is in the stage of preagony.

The natural clinical course of dementia presents a time frame in which to assess with perspective, from diagnosis, the complex decisions that the individual, or their representatives, must take in the later stages of the disease. This is the natural arena of shared care planning (SCP),12 Shared care planning is defined as the “communicative-deliberative, relational and structured process focussed on the individual and their context-network of support/carers (persons involved), which promotes conversations (communication spaces) that facilitate reflection and understanding of living with and experiencing the disease, the care and attention required throughout its entire clinical course, to make joint decisions at all times in accordance with the patient’s preferences, goals and expectations, from the present to coping with any future challenges, such as the patient losing their ability to decide for themselves”.13

Family doctors and/or the professional treating the early stages of dementia and who accompany the patient on their life journey can help in SCP, thereby minimising uncertainty in the advanced stages of the disease.14 To achieve this, the SCP process must be documented step by step in the medical record (MR).

It must be specified if the planned measures are understood as part of a treatment or as part of care. The scientific evidence clearly points towards the physiological and therapeutic futility of treatment. However, difficulty arises when care consideration is paramount to the decision-makers. Feeding is a symbol of care in the collective subconscious, and not feeding someone could be interpreted to be an attack by omission against the most vulnerable. Scientific societies debate the definitions of therapeutic terminology in clinical nutrition7,15 reinforcing the idea that EN is just another specialised medical treatment and, therefore, not initiating or withdrawing enteral tube feeding is considered ethically correct or equivalent decision.

Autonomy and refusal of treatmentThe right to autonomy is recognised by Law 41/2002,16 enabling subjects to take responsibility for their own decisions and take control of their lives. A patient is entitled to refuse a treatment if it means prolonging agony or a life of pain with no possibility of recovery. Refusing a specific treatment should not affect other therapies or basic care that the patient needs. The decision made by a person with AD regarding whether or not to administer EN should form part of a reflective and dynamic SCP process.

This SCP process includes providing sufficient and appropriate information about the scope of the disease, its clinical course, possible complications and treatments indicated in the various phases, and active listening to understand patients’ beliefs and values better. Making shared decisions as the disease progresses aims to facilitate the patient’s deliberation, laying the foundations for advanced care planning as far as possible so that the approach to disease progression is clinically and ethically correct. The main components and decisions of SCP are detailed in a document of advance directives (ADs) or prior instructions (PIs), including defining the role of the representative and their level of authority. ADs and PIs should not transform the process of reflection and deliberation into the automatic application of an almost always complex decision, and purely automated decisions should be avoided when applying this document.17,18

If there is no properly documented SCP process in the MR and there are no ADs or PIs, decisions should be made by representation, with this role undertaken by a close relative or friend, following two different schema: (1) if the patient expressed their wishes before becoming incompetent (“prior competence decision schema”); and (2) what the representative deems to be in the patient’s best interest or what the patient may prefer given the current situation (“best interest schema”).

Article 10 (on the right to refuse treatments) of Law 5/2015, of 26 June, on the rights and guarantees of the dignity of terminally ill people, applies the same legal regime to surgical, hydration and feeding procedures, as well as to artificial resuscitation or the withdrawal of life support measures, when they are extraordinary or disproportionate to prospects for improvement and cause disproportionate pain and/or suffering.19 In the specific case of AD, this refusal of treatment may have been collected at an earlier stage, in the mentioned SCP processes or in their documentation in the MD or the PI/advance directive documentation.

Terminal illness. Palliative care and end-of-life careTerminal illness is defined as an advanced, progressive and incurable illness without the apparent or reasonable likelihood of response to a specific treatment, which manifests with numerous concurrent problems or intense, multiple, multifactorial and changing symptoms that have a major emotional impact on the patient, family and medical team, closely related to the explicit or non-explicit threat of death and with a life expectancy of fewer than six months.20

In the clinical course of dementia, it is difficult to identify the specific point at which the patient requires palliative care. It seems clear that GDS stage 7 places the patient in the terminally ill category, allowing us to simultaneously evaluate both active and palliative treatments, as they are not mutually exclusive. These should cover all aspects of the individual, i.e., their physical, psychological, social and spiritual characteristics.

So-called “end-of-life care” is the care given to patients in their last weeks or days. A patient in the last days of their life is characterised by a decline in their physical and mental state, with intense weakness, bedridden, decreased consciousness, frequently associated confusional state and communication difficulties. In addition, these patients often have difficulty ingesting foods and medication, sometimes associated with decreased consciousness. In any case, it is important to consider that a dying person stops eating. At this point, end-of-life care aims to control the symptoms and make patients comfortable so they can pass away peacefully.

According to some authors, extreme caution is required when using “quality of life” criteria to make decisions about a patient with AD because the quality of life of these individuals is highly influenced by their surroundings and the quality of their care. Moreover, it is impossible to measure the patient’s internal experience objectively and respond to an excessively useful and, therefore, ethically insufficient foundation. The patient may have lost the ability to reason and interact with their surroundings. Still, it is impossible to know to what extent they may retain their capacity to experience emotions or have experiential interests. It should also not be forgotten that assessing the quality of life may be subject to age and lifestyle bias and discrimination or reflect socioeconomic deficits.21 It is important to remember that the best treatment for a terminal illness is the one that provides the best possible quality of life.

Frequently asked questionsWhat are the expected benefits of tube feeding for people with AD?The only benefits people with AD receiving enteral tube feeding may receive maintaining their body weight, alleviating dehydration and preventing these complications if administered in the early stages of malnutrition. Moreover, in a select group of patients, the stress caused by coughing and suffocation associated with oral intake could be reduced. At the same time, functional capacity for small activities of daily living may be maintained.22

However, it has not been shown that enteral tube feeding in AD offers any benefit in reducing the risk of aspiration pneumonia, improving nutritional status, functional status or quality of life, reducing the risk of developing pressure ulcers or increasing survival.6 Moreover, the potential risks and complications of tube placement, mechanical complications such as obstruction or migration, as well as aspiration, diarrhoea, fluid overload, loss of the pleasure of eating, use of sedatives, the need for mechanical restraint, nausea and vomiting, reduced social interaction and attention during meals must be taken into consideration.22

How could people with advanced dementia be fed comfortably?Failing to administer tube feeding is interpreted by relatives, or healthcare professionals as equivalent to “not feeding” or “letting them starve”, which raises difficult moral and ethical problems as the progressive weight loss and muscle atrophy invariably associated with organic deterioration in AD is witnessed.6 This could be misinterpreted as “they are not doing all that they can”.

This conflict could be avoided by explaining that the patient is not being abandoned and that their nutritional needs are still being met by assisted oral feeding (comfort feeding).23 This approach aims to ensure the individual is as comfortable as possible through an oral diet plan as an alternative to artificial nutrition, eliminating the concept of “there is nothing to do” in two ways:

- 1)

The patient will continue to be fed individually if possible, always with the aim of not causing further harm.

- 2)

The aims are the patient’s comfort and quality of life, avoiding invasive measures.

When a person with AD has feeding difficulties, a thorough medical assessment should be conducted, including the MR obtained from the relatives or care, home staff, physical examination, swallowing study and polypharmacy review, as well as assessment by the medical professionals responsible for their care.22 Once other potential causes of feeding difficulty have been ruled out, a personalised plan should be established, which will include the following:

- 1)

Adjusting the texture, viscosity, density and temperature of the food.

- 2)

Correcting posture when eating.

- 3)

Preserving a calm environment free from external stimuli and taking as much time as necessary.

- 4)

Adjusting dentures.

- 5)

Preventing constipation.

- 6)

Periodically reviewing medication.

- 7)

Counselling and educating relatives/carers.

The doctor should inform the family about the inevitable course of the disease and the pros and cons of EN. Clinicians should refrain from proposing the dichotomy “either we place a feeding tube, or we do nothing,” as the second option would be morally unacceptable to the family.23 The choice should be between enteral tube feeding or continuing with oral feeding and patient care to ensure they are as comfortable as possible, and always keeping in mind the question “what would the patient have wanted for him/herself?” when making decisions on their behalf.22

Comfort feeding is defined as successive oral feeding attempts until they cause discomfort or are refused by the patient.23 When a patient cannot eat, the plan consists of frequent interactions with the patient to ensure oral hygiene, caring oral communication or therapeutic physical contact.

How can the comfort and quality of life of people with AD be improved?Given that the therapeutic goal in AD cannot be to cure the patient, it should instead be focussed on the care, control and relief of symptoms. With regard to feeding difficulties, the approach to be adopted should be to continue with oral feeding or to administer enteral tube feeding, neither of which will alter the course of the disease.24

Enteral tube feeding significantly impacts the patient’s social interactions, given that they will often be left isolated in their room connected to a machine instead of sitting at the dining table. Moreover, the patient’s ability to taste and savour the food is lost, and they may pull out the feeding tube due to discomfort or not recognising it as part of their body, sometimes requiring mechanical restraint.6 As such, enteral tube feeding does not offer greater comfort or improved quality of life than oral feeding in people with AD.

What nutritional therapy would be best for AD?Prerequisites of artificial nutrition and hydration are an indication for medical treatment, the definition of a therapeutic goal to be achieved, the patient’s will, and their informed consent.5 If there is no documented SCP process in the MR or an advance directive or PI document, when making decisions on an AD patient’s behalf, it is very important to have a clear idea of what the patient values most highly or attributes most importance to (for example, the quality or quantity of life in these circumstances), in accordance with what they may have previously expressed (prior competence decision schema). In a study on comprehensive end-of-life dementia care, of those participants who expressed preferences on the use of artificial nutrition, 74% said they did not want it, 15% were open to an EN trial period, 8% expressed no particular preference, and just 3% were in favour of long-term enteral tube feeding.25

Given that the scientific literature does not currently support enteral tube feeding in AD4,5,22,26, assisted oral feeding (comfort feeding) should be the method of choice unless the person cannot swallow due to impaired consciousness.5,22,24

What should be done if the patient refuses to eat?Refusing to eat has been reported in some studies as the second indication for enteral tube feeding.27 Reduced eating reflects the natural progression of the disease, with persistent refusal being a symptom of its terminal nature.11 Relatives and carers should be given information about the different symptoms and phases of AD to enable them to establish a personalised care plan.1,4,26

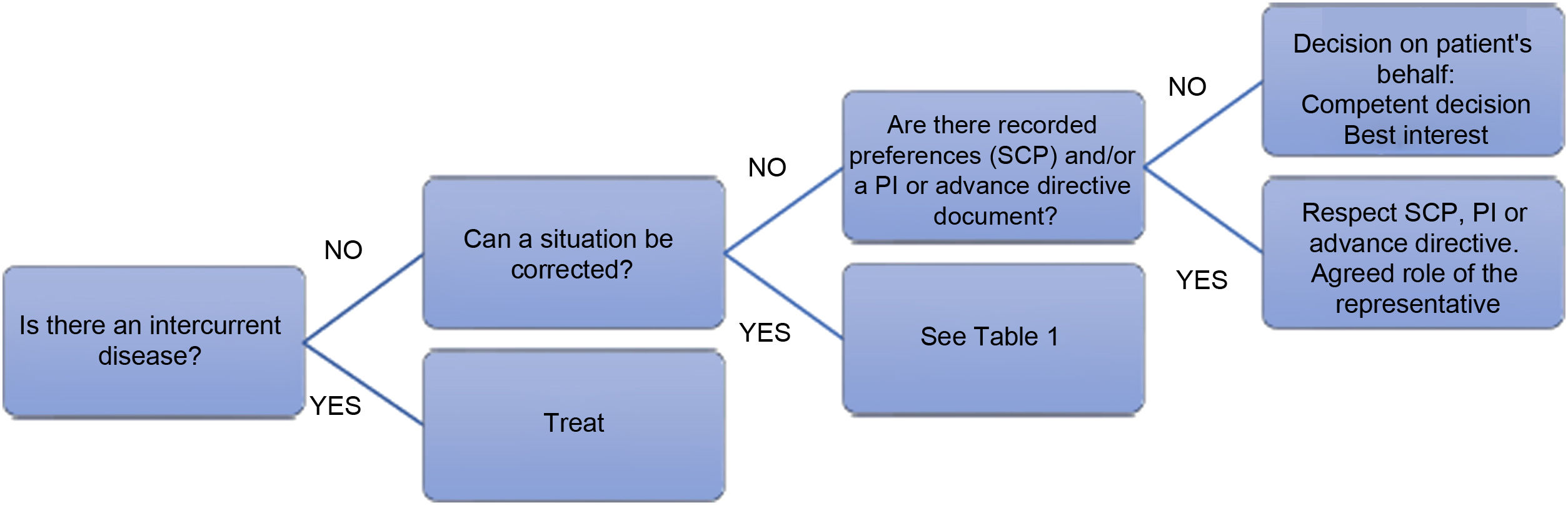

In the event of a refusal to eat, the effect of an intercurrent disease should be ruled out (Fig. 2), and attempts should be made to identify and correct any situation contributing significantly to the patient’s refusal to eat (Table 1).4,11,26,28–30 In practice:

- 1)

When refusal to eat is part of the natural progression of the disease, and this symptom is indicative of its terminal nature,11 EN by feeding tube/ostomy is not recommended4,11,26 and should only be administered in exceptional circumstances.26,31 Patient comfort should be promoted, alleviating dry mouth and maintaining comfort feeding as tolerated.28,29 Ensuring relatives are properly informed could help minimise the stress and anxiety this situation can cause.29

- 2)

When refusal to eat is the result of an intercurrent disease and where there is the prospect of being able to resume oral feeding once the acute condition has been resolved (for example, an infection), temporary EN could be indicated.5,26,32 If it is difficult to assess the risks and benefits in a particular situation, a trial period that includes specific goals may be reasonable.28 The Healthcare Ethics Committee should be consulted whenever clinicians are unsure how to proceed.

Main feeding problems in people with AD and corresponding intervention

| Problem | Intervention |

|---|---|

| Inappropriate environment at meal times | Eat in a calm and pleasant environment without rushing. |

| Do not use oral feeding while the patient is sleepy or upset. | |

| Assisted feeding should be personalised and given in a safe way that preserves the patient’s dignity. | |

| Oral health problems | Maintain good oral hygiene. |

| Adjust dentures as necessary. | |

| Applicable treatment for dental problems. | |

| Restrictive or monotonous diet | Avoid dietary restrictions. |

| Offer varied menus, paying attention to the look of the dish and personalising food to the patient’s needs and tastes. | |

| Enrich their diet with high-protein and high-energy foods. | |

| Dysphagia | Adjust the texture of the food. |

| Use thickeners and/or gelified water. | |

| Avoid foods with two textures or high-risk foods (sticky or fibrous foods, etc.). | |

| Use suitable utensils. | |

| Do not use syringes or straws. | |

| Place the patient in a suitable posture: seated or at 45° for up to half an hour after eating, with their back leaning on the backrest and their head bent slightly forwards. | |

| Follow the speech therapist’s recommendations if applicable. | |

| Sensory stimulation in cases of swallowing apraxia. | |

| Side effects of drugs and/or polypharmacy (excessive sedation, anorexia, xerostomia, nausea) | Adjust medication. |

| Other: odynophagia due to candidiasis, constipation, depression, anxiety, etc. | Specific treatment. |

AD: advanced dementia.

If the decision is made to place an enteral feeding tube, its actual and expected efficacy, goals to be achieved, and possible complications must be reported.31 With regard to complications, it is important not just to consider those inherent to EN (mechanical, infectious, metabolic complications, etc.), but also those that concern this group in particular:

- •

Loss of satisfaction and social interaction when comfort feeding is stopped completely.5 Maintaining oral feeding is recommended as long as it is possible and safe.28

- •

Poor oral hygiene, with increased risk of bacterial colonisation and aspiration pneumonia.29,33

- •

Risk of refeeding syndrome when starting EN.28,29

- •

Use of mechanical restraints or pharmacological treatments that prevent the patient from removing the feeding tube due to nervousness or anxiety.5,11,29,31

Given that suspending or not starting treatment are considered ethically equivalent, it is correct to suspend enteral tube feeding if patient re-assessment reveals that the expected goal has not been achieved, the patient’s general condition has worsened, or complications arise.5,11

What is the prognosis if a feeding tube is not placed?The clinical course of AD was described in the CASCADE study,34 which followed 323 patients with AD for 18 months. During this period, 54.8% of the participants died; median survival was 1.3 years. Feeding difficulties are part of the natural progression of the disease. After adjusting for age, gender and time since disease onset, the six-month mortality rate for patients with feeding problems was 38.6%.

Several attempts have been made to predict six-month survival in patients with AD. Still, none of the alternatives has shown good predictive capacity, meaning establishing a prognosis is problematic.35

What is the prognosis if a feeding tube is placed?In line with current scientific evidence, the leading scientific societies do not support the use of feeding tubes in patients with AD because this practice has not been shown to reduce the number of cases of aspiration pneumonia (it may even lead to an increase), prevent pressure ulcers or promote their healing, or improve nutritional status, survival or quality of life.4,5,11,26

The systematic reviews between 1999 and 2015 found no differences in mortality9,36–38, identifying the male gender and being over 80 as risk factors for mortality. An observational study in more than 3,000 care home residents with severe dementia who had a feeding tube placed reported a one-year mortality rate of 64.1%, with a median survival of 56 days after its placement. At the same time, one in five experienced a tube-related complication requiring hospitalisation.39

Similarly, placement of a gastrostomy tube has also shown no benefits in terms of survival40–43 albumin levels44 or pressure ulcers, regardless of the stage of the disease at which it is placed.10

Who should decide whether or not to place an NG tube? (Should we do what the family, the Ethics Committee or the treating doctor, etc. says?)

The decision to place an enteral feeding tube should be made as part of an SCP process with the patient and their family. The patient should be at the heart of all decisions made, and these decisions should be agreed upon and shared by the medical team and the patient’s relatives as far as possible.24 The medical team should discuss the current scientific evidence regarding tube placement for feeding and hydration with the patient and the family,45 as artificial nutrition and hydration are medical procedures, not simply the supply of food and fluids.5

Given the lack of benefits that EN offers AD patients and its potential adverse effects,27 both in clinical terms and quality of life, clinicians should not recommend the placement of an NG tube in these patients. However, it may sometimes be necessary to administer temporary EN to appease the families of AD patients, given that different religious beliefs or cultural differences could lead to conflicts between families or carers and the medical team, resulting in the temporary placement of an NG tube.5

Suspending artificial nutrition in a patient with AD should not be interpreted as an order not to feed that patient but rather as part of an overall care plan prioritising the patient’s comfort and quality of life. Part of this care entails maintaining oral intake and, when the patient refuses to eat, assuming that the patient is at the end stage of the disease4,5 the aim of care becomes to maintain the patient’s quality of life. This may trigger emotional and ethical conflicts with the relatives and carers, making it essential to explain the situation and the reasons for stopping treatment. It should also be explained what comfort feeding is and that not administering EN does not mean ceasing to care for the patient, seeking a second opinion or consulting the site’s Healthcare Ethics Committee if necessary.4

In accordance with the provisions of the Patient Autonomy Law16 compliance with any SCP documented in the MR must be guaranteed. The legal representative appointed by the patient for the implementation of the SCP must ensure that the patient’s wishes are enforced, even if contrary to the wishes of the representative. If the representative fails to make a timely decision for any reason, it will be the duty of the treating physician to start artificial nutrition by the available scientific evidence,6 which may be subsequently discontinued if the patient’s representative requests based on the patient’s PIs.11

In the event that consent must be granted by the patient’s legal representative without capacity to act, their decision shall be limited by the fundamental principle of “non-maleficence”, such that the decision that is in the best interests of the patient’s health must always by authorised. The role of the system and healthcare professionals will be to ensure that the guardians/representatives do not overstep their boundaries and, under the pretext of promoting the goodwill of their charge, are not acting to their detriment, that is, with maleficent intent.46

Therefore, within the field of EN, both its refusal and demand its administration in response to a decision that, from the objective perspective of the health and care of the represented patient, is maleficent has no value whatsoever. After exhausting a dialogue process with the representatives, the legal mechanisms outlined in Law47 should then be applied.

In conclusion, the SCP process documented in the MR or the advance directive or PI document should always be respected where one exists and where the circumstances described in said document apply. The patient’s legal representative must ensure their compliance. If there is no SCP process or AD or PI document, a consensus should ideally be reached with the patient’s relatives after explaining in detail the expected benefits and known risks to ensure that the decision of whether or not to place an NG tube is agreed upon mutually. If no such agreement can be reached, a second opinion may be sought, or the site’s Healthcare Ethics Committee consulted. As supporting resources, Table 2 presents ten golden rules to consider when addressing the key questions. In contrast, Table 3 offers guidance on addressing the situation and the approach to adopt with the patient and their relatives and representatives.

The ten golden rules.

| Advanced dementia is an irreversible and terminal disease. |

| Enteral tube feeding is a medical treatment and life support measure. |

| The best treatment for a terminal illness is the one that provides the best possible patient quality of life. |

| A patient is entitled to refuse a treatment if it means prolonging agony or a life of pain with no possibility of recovery. |

| Enteral tube feeding does not improve the quality of life or survival of patients with advanced dementia. |

| The aim of end-of-life care is to control symptoms and make the patient comfortable. |

| Assisted oral feeding (comfort feeding) is the method of choice for feeding a person with advanced dementia. |

| The decision whether or not to treat a person with advanced dementia by enteral tube feeding should be made by the patient through a shared care planning process documented in the medical record or in advance directives or prior instructions, including the role of the representative for the decision on the patient’s behalf (prior competence decision schema or best interest schema). |

| The decision not to treat a person with advanced dementia with enteral tube feeding does not mean the cessation of care or abandonment; their death will not be due to the lack of nutrition therapy but rather to the progression of the terminal disease. |

| Enteral tube feeding should be stopped if it does not have an indication or if the goal for which it was started is not achieved. |

Dos and don’ts.

| Do | Don’t | |

|---|---|---|

| Prognosis of AD with and without NG tube | Explain that EN is a medical treatment with indication and goal (to be re-assessed over time) and that it will not improve quality of life or survival | Create false expectations of improved quality of life and survival with enteral tube feeding |

| Role of EN in AD | Explain that EN is a medical treatment, with indication and goal (to be re-assessed over time), and that it will not improve quality of life or survival | Say that EN is the food that is going to be given to your relative to keep them alive |

| Role of comfort feeding in AD | Explain that comfort feeding is the best nutritional therapy in AD because it provides the greatest patient comfort and quality of life | Say that if an NG tube is not placed, we are not doing anything |

| Decision to place an NG tube in AD | Explain that the decision should be made by the patient, in accordance with the SCP established throughout their illness and their PIs/advance directives. If no SCP has been drawn up or if there are no PIs/ADs, through the decision by representation on the patient’s behalf: “What would the patient have wanted for him/herself?” or best interest criterion: “What is in the patient’s best interests right now?” | Say that the relatives have to decide whether to place a NG tube or do nothing |

| Decision to not place NG tube in AD | Explain that not placing an NG tube does not mean the patient will be abandoned or their care stopped and that the ultimate cause of death will be disease progression | Say that, if a NG tube is not placed, the patient will die of hunger |

| Refusal to eat | Rule out intercurrent disease, correct situations that could contribute to the patient’s refusal to eat | Say that the solution is to place a NG tube to feed the patient |

AD: advanced dementia; EN: enteral nutrition; NG tube: nasogastric tube; PIs/ADs: prior instructions/advance directives; SCP: shared care planning.

Protection of people and animals in research. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that patient data are not disclosed in this article.

Protection of patient data. The authors declare that patient data are not disclosed in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.