Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a common problem among older female. The usual treatment for POP is surgery but there are high recurrence rates, with a 29% reoperation rate. This study aims to identify risk factors for both primary prolapse and recurrence after surgical treatment.

MethodsRetrospectively assessment of clinical records of patients who underwent surgery for POP in a 10-year period. Statistical analysis was performed using the version 26.0 of Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS®) software.

Results746 women entered our study. The population was predominantly post-menopausal, multiparous, and obese/overweight. The most affected compartment was the anterior. Almost 90% of the patient presented with major prolapse. Being overweight or obese, having apical compartment POP, major POP or all compartment POP were risk factors for recurrence with statistical significance. The recurrence rate was nearly one-third but the reoperation incidence was low, reaching less than 6%.

ConclusionsPOP surgery has a high satisfaction rate. The only modifiable risk factor for recurrence is being overweight/obese and a nutritional plan should be considered before surgery so we can achieve the best possible results.

El prolapso de órganos pélvicos (POP) es un problema común entre las mujeres. El tratamiento habitual del POP es la cirugía, pero existen altas tasas de recurrencia, con una tasa de reintervención del 29%. Este estudio tiene como objetivo identificar los factores de riesgo tanto para el prolapso primario como para la recurrencia después del tratamiento.

MétodosEvaluación retrospectiva de historias clínicas de pacientes intervenidos por POP en un período de 10 años. El análisis estadístico se realizó utilizando la versión 26.0 del software Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS®).

ResultadosIngresaron a nuestro estudio 746 mujeres. La población era predominantemente posmenopáusica, multípara y obesa/con sobrepeso. El compartimento más afectado fue el anterior. Casi el 90% de los pacientes presentó prolapso mayor. Tener sobrepeso u obesidad, tener POP de compartimento apical, POP mayor o POP de todos los compartimentos fueron factores de riesgo de recurrencia con significación estadística. La tasa de recurrencia fue de casi un tercio, pero la incidencia de reintervención fue baja, alcanzando menos del 6%.

ConclusionesLa cirugía POP tiene un alto índice de satisfacción. El único factor de riesgo modificable de recurrencia es el sobrepeso/obesidad y se debe considerar un plan nutricional antes de la cirugía para que podamos lograr los mejores resultados posibles.

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a progressive descent of one or more pelvic organs through the urogenital diaphragm due to a lack of support of the anterior vaginal wall, posterior vaginal wall, vaginal cuff or uterus.1,2 The defects can affect more than one compartment at the same time.3 It is a common condition affecting women worldwide with important impact in the quality of life.4 The prevalence of POP throughout the general population can reach 50% based on anatomic criteria, however, based solely on patients’ symptoms, it affects only 2.9–8%.1,5 Women with POP usually complaint of urinary symptoms as urinary retention, increased risk for urinary tract infection and urinary incontinence/urgency, bowel symptoms as obstructive defecation or fecal incontinence and symptoms of vaginal bulge, pressure, pain and dyspareunia.4,6 Additionally, if the prolapsed organ progress beyond the hymenial ring, as a result of erosions from the vaginal wall or cervix, patients may report vaginal bleeding.2

The etiology of pelvic floor disorders is usually multifactorial but commonly known risk factors are pregnancy, multiparity, vaginal delivery, older maternity age, obesity, heavy work, constipation, race, smoking and aging.7,8 The treatment of POP is commonly surgical and it is estimated that the lifetime risk of undergoing such procedure is between 12 and 20% for menopausal women.3,9 As POP is a non-life treating condition, asymptomatic women have no indication for surgery as the procedure is of uncertain benefit and adds peri and postoperative risks.1 Since pelvic floor repairing surgery aims to restore anatomical support of pelvic organ structures, one of its major challenges is the high recurrence rate that can reach 6–20% at 10-years with some studies suggesting a second surgery approximately one third of the time.1,4,10 However, not all surgical techniques reported the same recurrence rate. A surgical technique is classified as ‘native tissue repair’ when only pelvic organ support tissue is used. As native tissue repairs showed discouraging rates of failure, repairs using other material (prosthesis or graft) to reinforced the defective tissue, known as synthetic mesh became popular.1,3 However, the rise in mesh placement was accompanied by increased reports of mesh related complications such as mesh exposure. Following this evidence, the European Urology Association and the European Urogynaecological Association issued a consensus that only complex cases with previous failure procedures should use transvaginal mesh.11

Although recurrence risk factors have been analyzed in previous works, they are not as well documented as those for development of POP. They suggest advanced preoperative stage as a risk factor for POP relapse as well as family history and obesity.9

This study aims to identify risk factors for both primary prolapse and recurrence after surgical treatment.

Materials and methodsRetrospectively assessment of the clinical records of patients who underwent surgery for POP in our department in a 10-year period (February 2010–January 2020). Data collection was performed in ongoing, retrospective fashion.

In order to obtain the greatest statistical significance, all the interventional patients were included and therefore, the sample size was not calculated.

The baseline evaluation included past medical history and physical examination. The degree of POP was quantified using the POP-Q system, which is the grading system most diffusely used due to its proven interobserver and intraobserver reliability.3 We considered major prolapse if the patient had at least on compartment with a degree ≥3. Symptomatic POP was defined as any complaint relating to bothersome vaginal bulge or other prolapse related symptoms.

The type of surgery that the patients were submitted to depended on several factors. There was an individualized approach to each patient according to the preferences and technical experience of the surgical team. The mesh kits used were Prolift® (Johnson and Johnson's, Ethicon, Sommerville, NJ, USA), Perigee® (AMS, Inc., Minnetonka, MN, USA) and IVS® (IVS Tunneler, Tyco Healthcare Group, Norwalk, Conn, USA), all of which are made of polypropylene. The mesh used in every case was determined by commercial availability at the time of surgery.

Statistical analysis was performed using the version 26.0 of Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS®) software. Statistical significance was defined as a P value less than 0.05. The demographic and clinical characteristics of participants were reported as mean and standard deviation, or number count and frequency as appropriate. The sample was analyzed descriptively as a whole and then compared as patients who relapse and patients who did not relapse. All data sets were tested for Gaussian distribution with the Shapiro–Wilk test and curve symmetry. A parametric approach was chosen because the normality principles were not fulfilled. The t-student test was computed to compare continuous variables between the two independent groups. Categorical and nominal variables were compared using the chi-squared test, or Fisher exact test whenever appropriate.

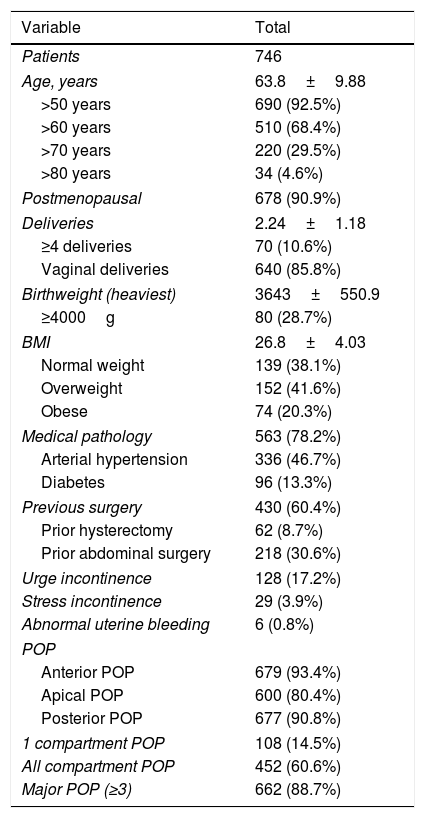

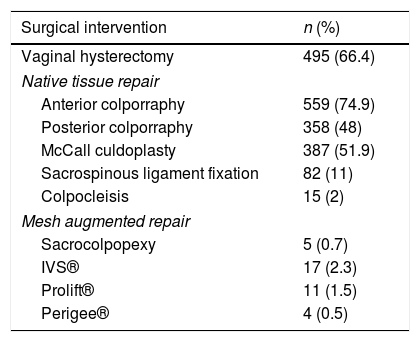

ResultsA total of 746 women underwent surgical procedure for POP, in our department, in the 10-year period. Their demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and the surgical interventions in Table 2.

Patients demographics and characteristics.

| Variable | Total |

|---|---|

| Patients | 746 |

| Age, years | 63.8±9.88 |

| >50 years | 690 (92.5%) |

| >60 years | 510 (68.4%) |

| >70 years | 220 (29.5%) |

| >80 years | 34 (4.6%) |

| Postmenopausal | 678 (90.9%) |

| Deliveries | 2.24±1.18 |

| ≥4 deliveries | 70 (10.6%) |

| Vaginal deliveries | 640 (85.8%) |

| Birthweight (heaviest) | 3643±550.9 |

| ≥4000g | 80 (28.7%) |

| BMI | 26.8±4.03 |

| Normal weight | 139 (38.1%) |

| Overweight | 152 (41.6%) |

| Obese | 74 (20.3%) |

| Medical pathology | 563 (78.2%) |

| Arterial hypertension | 336 (46.7%) |

| Diabetes | 96 (13.3%) |

| Previous surgery | 430 (60.4%) |

| Prior hysterectomy | 62 (8.7%) |

| Prior abdominal surgery | 218 (30.6%) |

| Urge incontinence | 128 (17.2%) |

| Stress incontinence | 29 (3.9%) |

| Abnormal uterine bleeding | 6 (0.8%) |

| POP | |

| Anterior POP | 679 (93.4%) |

| Apical POP | 600 (80.4%) |

| Posterior POP | 677 (90.8%) |

| 1 compartment POP | 108 (14.5%) |

| All compartment POP | 452 (60.6%) |

| Major POP (≥3) | 662 (88.7%) |

Continuous variables are expressed with mean±SD and qualitative variables with n (%).

Surgical interventions.

| Surgical intervention | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Vaginal hysterectomy | 495 (66.4) |

| Native tissue repair | |

| Anterior colporraphy | 559 (74.9) |

| Posterior colporraphy | 358 (48) |

| McCall culdoplasty | 387 (51.9) |

| Sacrospinous ligament fixation | 82 (11) |

| Colpocleisis | 15 (2) |

| Mesh augmented repair | |

| Sacrocolpopexy | 5 (0.7) |

| IVS® | 17 (2.3) |

| Prolift® | 11 (1.5) |

| Perigee® | 4 (0.5) |

A small percentage of patients (6.2%, 46) did not attend the postoperative visit and do not have follow-up data. Mean follow-up was 12.9 months (±12.7); with the majority of women (446; 63.7%) having follow-up of ≥6 months. Only 47 women presented postoperative complications (6.3%). The most frequent were urinary tract infection (17), post-op fever of unknown cause (11), hemorrhage (3) and vaginal cuff hematoma (3). There was one case of post-operative death, of unrelated causes. Less than a third (30.3%, 212) of the patients who underwent surgery had anatomical recurrence of the POP. Only 9.5% of the mesh augmentation group relapsed vs 28.8% of the native tissue repair arm. The majority of them were asymptomatic and did not required any further intervention or treatment. Only 70 recurrences (33%), 10% of all the women who had had at least one follow-up appointment, were major prolapses. Twenty patients were treated for minor symptomatology with topic estrogen, 3 did physiotherapy and 5 were eligible for pessary placement. More than half (62.9%, 44) of the recurrence major prolapses required further surgical intervention. Twenty-eight women (63.6%) underwent native tissue repair surgery, of which 12 were submitted to anterior colporraphy, 9 to posterior colporraphy, 9 underwent an obliterative procedure – colpocleisis, 6 Sacrospinous ligament fixation and 3 vaginal hysterectomy. The other 16 underwent mesh augmented repair, of which 7 sacrocolpopexy, 7 Prolift® and 2 Perigee®. Three patients (9.4%) presented complications related to the mesh, namely, vaginal exposure; in 1 case the patient was asymptomatic and treated with topic estrogen. In the other two cases, the exposure was associated with vaginal discharge and required partial mesh removal in the operation room. The satisfaction rating was high, with an overall reintervention rate of 5.9%.

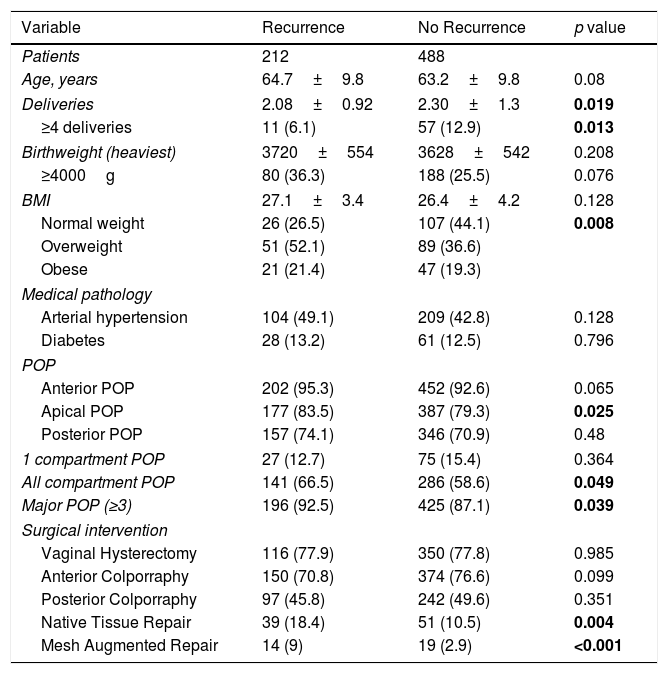

Data regarding comparison by groups between patients who relapse after surgery and patients who did not are shown in Table 3. There was no statistical difference regarding patient age, birthweight of the heaviest newborn or number of newborns weighing ≥4000g. Also, we found no significance in differences towards previous medical conditions, having anterior or posterior prolapse, or having prolapse exclusively of 1 compartment.

Sample characterization and comparison (recurrence vs no recurrence patients).

| Variable | Recurrence | No Recurrence | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 212 | 488 | |

| Age, years | 64.7±9.8 | 63.2±9.8 | 0.08 |

| Deliveries | 2.08±0.92 | 2.30±1.3 | 0.019 |

| ≥4 deliveries | 11 (6.1) | 57 (12.9) | 0.013 |

| Birthweight (heaviest) | 3720±554 | 3628±542 | 0.208 |

| ≥4000g | 80 (36.3) | 188 (25.5) | 0.076 |

| BMI | 27.1±3.4 | 26.4±4.2 | 0.128 |

| Normal weight | 26 (26.5) | 107 (44.1) | 0.008 |

| Overweight | 51 (52.1) | 89 (36.6) | |

| Obese | 21 (21.4) | 47 (19.3) | |

| Medical pathology | |||

| Arterial hypertension | 104 (49.1) | 209 (42.8) | 0.128 |

| Diabetes | 28 (13.2) | 61 (12.5) | 0.796 |

| POP | |||

| Anterior POP | 202 (95.3) | 452 (92.6) | 0.065 |

| Apical POP | 177 (83.5) | 387 (79.3) | 0.025 |

| Posterior POP | 157 (74.1) | 346 (70.9) | 0.48 |

| 1 compartment POP | 27 (12.7) | 75 (15.4) | 0.364 |

| All compartment POP | 141 (66.5) | 286 (58.6) | 0.049 |

| Major POP (≥3) | 196 (92.5) | 425 (87.1) | 0.039 |

| Surgical intervention | |||

| Vaginal Hysterectomy | 116 (77.9) | 350 (77.8) | 0.985 |

| Anterior Colporraphy | 150 (70.8) | 374 (76.6) | 0.099 |

| Posterior Colporraphy | 97 (45.8) | 242 (49.6) | 0.351 |

| Native Tissue Repair | 39 (18.4) | 51 (10.5) | 0.004 |

| Mesh Augmented Repair | 14 (9) | 19 (2.9) | <0.001 |

Continuous variables are expressed with mean±SD and qualitative variables with n (%).

Although there were no statistically significant differences in relation to the average BMI, dividing the patients by the respective groups, namely normal weight, overweight and obesity, we observed that the patients who relapse have more rates of overweight and obesity, with significance. Also, we found that the recurrence group had lower mean deliveries and a lower rate of multiparous women (≥4 deliveries) and that difference was statistically significant. There were significant differences between patients in the recurrence and no recurrence groups considering major prolapses, with superior percentage of women in the recurrence group and also regarding 3 compartment prolapse, with similar results.

The recurrence group also had a higher percentage of women with apical prolapse and higher number of procedures, both with native tissue or with mesh prothesis, and all the above had statistical significance.

DiscussionPelvic organ prolapse is a common condition in the female population, but it does not constitute a “life-threatening” pathology and, as such, its treatment should aim to restore the normal functioning of the structures in order to decrease the symptoms and improve the quality of life. There are several surgical techniques for the treatment of POP, including vaginal or abdominal approaches, with or without the use of prosthetic material. The choice for a particular technique or mesh must be individualized and always considering the risks and benefits inherent to each.

In our sample of 746 women, we reported age and postmenopausal status as two non-modifiable risk factors, affecting 92.5% and 90.9% of patients, respectively, factors previously studied and reported in the literature.6,12 According to Peker,13 vaginal delivery presented itself as an independent risk factor for prolapse with 85% of women reporting having had at least 1 vaginal delivery, although parity, unlike other authors,1,12 did not had an increased expression as a predictive factor, taking into account that the average parity was 2.24 births and only 10.6% of the sample was presented as a big multiparous, which we considered as having 4 or more births. Macrosomia, more than the multiparity itself, seemed to have its role as a POP predictor, as 28.7% of the patients had newborns weighing more than 4000g. Also widely described as a risk factor,8 61.9% of the sample population was obese or overweight, despite the average BMI being borderline between the range of values considered normal weight and overweight, 26.8kg/m2. Although most pathologies associated with POP are connective tissue diseases or gastrointestinal disorders that lead to constipation,1,14 in our sample the most frequently reported pathologies were arterial hypertension, affecting almost half of the patients evaluated, followed by diabetes mellitus with an incidence of 13.3%. As a pelvic floor disorder, POPs were accompanied by complaints of urinary incontinence in 21.1% of cases, values similar to those documented by Hage-Fransen.7

We report a high rate of major prolapse and prolapses in all compartments, respectively 88.7% and 60.6%, meeting what was previously reported by Paz-Levy10 or Mironska4 and, as Kalkan1 describes in his work, the anterior compartment was the most affected, affecting 93.4% of all operated patients.

The type of surgery that the patients were submitted to depended on several factors. There was an individualized approach to each patient according to the preferences and technical experience of the surgical team. The surgical objective was always to improve the quality of life, with lowest possible recurrence rate.

It is well known that the high recurrence rate is one of the biggest problems associated with POP correction surgery.1,9,15 Our sample presented values similar to those already reported by Patel,5 approximately 30%, although higher than the 13.7% reported in some recent works.10 This significant difference between works is often related to the definition of recurrence, some authors define it by anatomical criteria while others use the patient's symptomatology. Most recent, some authors proposed to use “composite” variables to define POP surgical success, which include anatomical criteria as well as patient's symptomatology and the need for reinterventions.16

There are, in fact, longitudinal cohort studies with longer series, including both native tissue repair and the use of meshes17,18 or only native tissue repair19 who have also indicated high rates of anatomic recurrence, ranging from 45% to 55%. In our study, only anatomical criteria were used, if criteria related to the patient's symptoms had been used, the percentage would probably be lower, which can be indirectly observed by the lower percentage of patients who, despite clinical recurrence, had to undergo a second intervention, in this case only 5.9% of the initial population, or about 7.5% with grade 3–4 recurrences, similar to the 6.8% reported by Diez-Itza.9

Usually, the reasons for using mesh are the high anatomic cure rated and superior objective efficacy. These cure rates can reach 90%,3 similar to our 9.5% of relapse incidence on the women that underwent mesh augmented repair. The main reason for not using a mesh is mesh related complications. We had a mesh related complication rate of 9.4%, namely mesh extrusion. It is a lower value compared with similar studies5 that report rates of 19% but similar to Feiner20 (4.6–10.7%). However, 66.6% of the patient with this type of complications required surgical intervention to repair the damage which is higher than the 58% reported by Patel5 but we have to consider that overall, there were just 3 cases.

There is a significant variation between native tissue and mesh repair when it comes to effectiveness, likewise the definition of recurrence, as mentioned before. This is why recent studies present relapse rates for native tissue repair that range between 22 and 51%.3,16 Our study shows recurrence rates for native tissue repair of 28.8%, in the lower range limit.

Despite not being as low values as those presented in the mesh group, we have to be aware that the number of patients undergoing native tissue surgery was significantly higher and the results may be biased by this difference. This way, it is not possible for the authors to compare results of women with native repair and meshes. As already mentioned, overall, there was a good satisfaction rate with a re-surgery rate of less than 6%, regardless of the procedure.

Preoperative POP-Q stage is an established risk factor for anatomic recurrence in POP surgery.21,22 The meta-analysis performed by Friedman et al.21 indicates that POP stage 3–4 increased the risk of recurrence 2.11 fold. Weemhoff18 found a two-fold increase in risk of prolapse recurrence for POP stage 3–4. Our study, with a larger sample than the previous presented, revealed that major prolapse (stage 3–4) are a frequent gradient in POP requiring surgery and its incidence is superior in the recurrence group, with this difference being statistically significant (p=0.039). These results reinforce the importance of preoperative POP-Q stage on the risk of primary prolapse and posterior recurrence and allows clinicians to better program type of surgery as the probable mechanism by which severe prolapse favors recurrence reflects major tissue damage to pelvic floor structures and consequently a greater likelihood of failure after traditional tissue repair. Other factors concerning POP-Q evaluation that had demonstrate significancy as risk factors for recurrence were the 3 compartments prolapse and the apical prolapse (p=0.049 and p=0.025, respectively). These data demonstrate the relevance of apical prolapse in post-correction outcomes. This compartment is sometimes less addressed by the importance already established of the anterior compartment as the most affected and as a prognostic factor, but it should have been taken into account in the initial surgical planning.

Age at diagnosis was not a risk factor for recurrence as it is for prolapse per se, confirming the findings of other authors.19,21,22 Also, vaginal deliveries were a risk factor for POP but not for recurrence as the recurrence group had lower rates of>4 deliveries than the no recurrence group, and this difference was statistically significant (p=0.013). The same literature21,22 also defends that there is no relationship between BMI with POP recurrence but in our study, we had higher rates of women in the overweight and obese group that had recurred (p=0.008).

Our work showed no significance differences in rates of vaginal hysterectomy, anterior colporraphy and posterior colporraphy between women of both groups (recurrence and no recurrence) which defends the theory that basic procedures don’t interfere with the outcomes.

However, comparing women who had recurrence with the ones who did not recurred, we can see that there were higher rates of women who had had more complex surgery, with native tissue repair or mesh augmented repair in the recurrence group (10.5% vs 18.4%, p=0.004 and 2.9% vs 9%, p<0.001). This may say that the initial degree of prolapse and, therefore, the patient's natural and intrinsic tendency to have tissue changes to condition prolapse, is in itself one of the factors with the greatest implications for the recurrence rate. Patients with a worse prognosis at the first approach, initially proposed for surgery with native tissues and mesh, relapsed more.

The main strengths of our study are the large collected sample and the high follow-up rate with a mean follow-up of almost 13 months. Also, is a 10-years retrospective study which gives time to patients to relapse and observe the eventual outcomes on a second surgery. Another main distinguishing characteristic is that only women with primary prolapse surgery were included in the study, avoiding the potential bias of previous prolapse surgery in risk factor analysis.

One of the limitations is that it is a retrospective study and it doesn’t allow us to obtain other results that could enrich the paper as the rate of symptomatic recurrence and to better evaluate the POP related symptoms. Despite these limitations, the study confirms that major defects in pelvic floor support structures before surgery are associated with higher recurrence rates, regardless the type of repair (native tissue vs mesh). Also, higher BMI is a high-risk factor for recurrence and the only identified that is modifiable. The preoperative identification of these risk factors is extremely important for a better therapeutical optimization and increase satisfaction rates.

ConclusionPelvic organ prolapse is a common problem affecting up to 50% of women based on anatomic criteria. There are well known risk factors associated with POP, most of them non modifiable. Overweight and obesity is the only modifiable factor to improved recurrence rates. Major defects in pelvic floor support structures are associated with higher relapse rates but, overall, there is a high satisfaction after first surgery when candidates are well studied and the chosen surgery technique is individualized.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Author's contributionF. Coutinho: Project development, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing.

M. Veiga: Data collection.

R.S. Carvalho: Project development, data collection.

S. Mineiro: Project development.

F. Nunes: Project development.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.