Epidemiological evidence suggests adherence to vegetable-rich diets is associated to atheroprotective effects and bioactive components are most likely to play a relevant role. The notion of inter-kingdom regulation has opened a new research paradigm and perhaps microRNAs (miRNAs) from edible vegetables could influence consumer gene expression and lead to biological effects. We aimed to investigate the potential impact of broccoli-derived miRNAs on cellular cholesterol efflux in vitro.

MethodsFour miRNAs (miR159a, miR159b, miR166a and miR403) from Brassica oleracea var. italica (broccoli), a widely consumed cruciferous vegetable, were selected for further investigation, based on their high abundancy in this vegetable and their presence in other plants. Selected miRNAs were synthesized with a 3′-terminal 2′-O-methylation and their cellular toxicity, in vitro gastrointestinal resistance and cellular uptake were evaluated. Potential target genes within the mammalian transcriptome were assessed in silico following pathway analysis. In vitro cholesterol efflux was assessed in human THP-1-derived macrophages.

ResultsmiRNAs survival to in vitro GI digestion was around 1%, although some variation was seen between the four candidates. Cellular uptake by mammalian cells was confirmed, and an increase in cholesterol efflux was observed. Pathway analysis suggested these miRNAs are involved in biological processes related to phosphorylation, phosphatidylinositol and Wnt signaling, and to the insulin/IGF pathway.

ConclusionsHealth-promoting properties attributed to cruciferous vegetables, might be mediated (at least in part) through miRNA-related mechanisms.

La evidencia epidemiológica sugiere que la adherencia a dietas ricas en vegetales está asociada con efectos ateroprotectores y probablemente los componentes bioactivos desempeñen un papel relevante. La noción de regulación entre reinos ha abierto un nuevo paradigma de investigación y tal vez los micro-ARN (miARN) de vegetales comestibles podrían influir en la expresión genética de los consumidores y provocar efectos biológicos. Nuestro objetivo fue investigar el impacto potencial de los miARN derivados del brócoli sobre la exportación de colesterol celular in vitro.

MétodosCuatro miARN (miR159a, miR159b, miR166a y miR403) de Brassica oleracea var. italica (brócoli), un vegetal crucífero muy consumido, fueron seleccionados para su caracterización, en base a su alta abundancia en este vegetal y su presencia en otras plantas. Los miARN seleccionados se sintetizaron con una 2’-O-metilación 3′-terminal y se evaluaron su toxicidad celular, resistencia gastrointestinal in vitro y absorción celular. Los posibles genes diana dentro del transcriptoma de mamíferos se evaluaron in silico después del análisis de rutas. Se evaluó la exportación de colesterol in vitro en macrófagos humanos derivados de THP-1.

ResultadosLa supervivencia de los miARN a la digestión GI in vitro fue de alrededor del 1%, aunque se observó cierta variación entre los 4 candidatos. Se confirmó la absorción celular por células de mamíferos y se observó un aumento en la exportación de colesterol. El análisis de las vías de señalización sugirió que estos miARN están involucrados en procesos biológicos relacionados con la fosforilación, el fosfatidilinositol y la señalización Wnt, y con la vía insulina/IGF.

ConclusionesLas propiedades beneficiosas sobre la salud atribuidas a las crucíferas podrían estar mediadas (al menos en parte) a través de mecanismos relacionados con los miARN de la dieta.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain the main cause of mortality worldwide. Diet plays a bidirectional role in the development and progression of CVDs. Adherence to a Western-style diet based on the intake of high amounts of kcal, lipids and simple sugars, accompanied by low intake of fiber and bioactive compounds, contributes to the deregulation of lipid metabolism.1 However, epidemiological evidence suggests that adherence to diets rich in vegetables, especially from the brassica family, shows an atheroprotective effect, reducing the risk of suffering from associated cardiovascular pathologies.2 The arteriosclerotic process begins after the pathological alteration of lipid metabolism, which is why bioactive components (such as polyphenols like catechins, resveratrol, and curcumin) with activity on lipid metabolism have been sought.3,4

miRNAs, whose biological function is conserved among mammals and plants, are posttranscriptional regulators of gene expression and play a pivotal role in many diseases, including atherosclerotic CVD. miRNAs post-transcriptionally control different aspects of cellular cholesterol homeostasis, including cholesterol efflux. Cholesterol efflux as the first and probably most important step in reverse cholesterol transport is an important biological process relevant to HDL function.5,6

Plant miRNAs play a fundamental role in essential plant biological processes such as growth, development, stress response and metabolism.7,8 Although the biogenesis of plant and animal miRNAs has certain similarities, plant miRNAs present methylation in the 2′-OH position of the ribose located in the 3′ terminal region, which render them greater resistance to enzymatic degradation.9

Increasing evidence suggests that miRNAs from other kingdoms (e.g. plants) show a certain degree of similarity to mammals. Some authors suggest that plant miRNAs could also resist the harsh conditions of the digestion process and be absorbed, thus facilitating their possible role as a gene regulator. This phenomenon is known as cross-kingdom regulation. The first evidence of transfer of miRNAs from plants to mammals, accompanied by a regulatory effect on gene expression, was described by Zhang et al.10 In this study, authors found that MIR168a – a highly expressed miRNA in rice – resists the harsh conditions of the gastrointestinal tract, reaching circulation and even distant organs such as the liver. There, it regulates the expression of the low-density lipoprotein receptor adapter protein 1 (LDLRAP1), inhibits its hepatic expression and, consequently, reduces plasma LDL clearance.10 Also, plant miRNAs seem to have beneficial effects in other diseases, such as cancer.11 After these pioneering studies, several other studies on the arena of regulation between kingdoms have been reported, either supporting or unsupporting the cross-kingdom possibility.12 Different biological effects associated to plant miRNAs have been described in mammalian models, including a role in inflammatory processes,13 metabolism,14 cancer,15 and viral infection,16 among others. However, a potential role in cholesterol efflux has not been previously reported.

Confirming a role of diet-ingested miRNAs on host‘s gene expression regulation could revolutionize the current paradigm of nutrition. In this sense, a new way to explore dietary and therapeutic alternatives that might contribute to reducing the incidence of chronic diseases could begin with the identification of miRNAs derived from plant-derived foods, such as broccoli. Given the above, the objective of this work was to explore whether certain miRNAs from broccoli could act as potential regulators of cellular cholesterol efflux.

Materials and methodsMaterialsPlant miRNAs were synthesized in a single-stranded form with methylation at the 3′-OH end (characteristic of plant miRNAs9) (Dharmacon®, Horizon Discovery, Waterbeach, UK).

Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) was purchased from local supermarkets (Madrid, Spain) and refrigerated until use. Next, broccoli inflorescences were selected and ground (TissueRuptor II; Qiagen, Denmark) in the presence of QIAzol (Qiagen) to avoid RNA degradation during the grinding process.

RNA isolationTotal RNA from broccoli tissue was isolated using Qiagen's miRNeasy® Mini Kits, following the manufacturer's instructions. Purified RNA was eluted in 100μL of RNase-free water.

Small RNA sequencing and data analysisRNA quality and integrity was evaluated using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies). Library preparation and sequencing was carried out at the “Fundación Parque Científico de Madrid” (Madrid, Spain), using the NEBNext® Multiplex Small RNA Library Prep Set (Illumina®) and following the manufacturer's recommendations.

After sample preparation, sequencing was performed using the NextSeq 500 High Output v2.5 kit (Illumina) in 1×75 single read sequencing on a NextSeq 500 Sequencer (Illumina). FASTQC tool was used for assessing reads quality control. Bowtie2 was used for sequence alignment, using the sequences from the miRBase V21 library as references.17 RNAs counts were used to determine the families of miRNAs present in broccoli.

Gastrointestinal digestionIn vitro digestion was carried out following the conditions of a previously standardized method (Minekus et al.29) and applied to miRNA samples (Del Pozo-Acebo et al.25). The oral phase was composed of a salivary electrolyte solution (18.8mM K+; 13.6mM Na+; 19.5mM Cl−; 3.7mM H2PO4−; 13.7mM HCO3−; 0.15mM Mg2+; 0.12mM NH4+; 1.5mM Ca2+) and human saliva α-amylase Type IX-A (75U/mL) (EC 3.2.1.1, Sigma-Aldrich), at a pH of 7.0. The gastric phase was formed by a gastric electrolyte solution (7.8mM K+; 72.2mM Na+; 70.2mM Cl−; 0.9mM H2PO4−; 25.5mM HCO3−; 0. 1mM Mg2+; 1mM NH4+; 0.15mM Ca2+) and porcine pepsin (2000U/mL) (EC 3.4.23.1, Sigma-Aldrich), at a pH of 2.5–3.0. The intestinal phase was formed by the gastric phase plus an intestinal electrolyte solution (7.6mM K+; 123.4mM Na+; 55.5mM Cl−; 0.8mM H2PO4−; 85mM HCO3−; 0.33mM Mg2+; 0.6mM Ca2+), 24mg/mL of porcine bile extract (EC 232-369-0, Sigma-Aldrich) and pancreatin (800U/mL) (EC 232-468-9), at a pH of 7.0.

Initially, miRNA samples were mixed with an equal volume of oral phase and placed at 37°C with slow stirring for 2min. Subsequently, the gastric phase was added to the solution (1:1) and digested at 37°C with slow stirring for 1h. The resulting solution was finally mixed with the intestinal phase solution (1:1) and kept at 37°C with slow stirring for 2h. Samples were collected at different timepoints throughout the complete digestion period.

Human THP-1 cultureHuman THP-1 monocytes (ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Gaithersburg, USA) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Madrid, Spain) and supplemented with 10% FBS, 100U/mL penicillin, 100mg/mL streptomycin, 2mM l-glutamine, at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2. Cells were seeded at a density of 5×105cells/mL in 24-well plates. THP-1 monocytes were differentiated into macrophages (THP-1/M cells) in the presence of 100ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma, Madrid, Spain), for 72h.

MiRNA transfectionAfter differentiation, cells were washed with PBS and transfected with exogenous miRNAs or controls, for 48h. To achieve this, a mixture of single-stranded miRNAs – ath-miR159a, ath-miR159b-3p, athmiR166b-3p, and ath-miR403-3p – with methylation at the 3′-OH end (Dharmacon®) was synthesized. Each miRNA was set at 5nM and a mimic control miRNA without any target in the human genome (Dharmacon®) was used as a negative control. miRNAs were diluted in 1× siRNA buffer (Thermo Fisher) and incubated with Lipofectamine RNAi max (Invitrogen, Thermo Scientific), for 30min, at room temperature. After 30min, culture medium was replaced with 150μL of the miRNAs mixture and 150μL of Opti-MEM™ serum-reduced medium (Thermo Fisher). After 8h of incubation, 300μL of 2× RPMI 1640 culture medium was added. Forty-eight hours later, the medium rich in exogenous miRNAs was removed and RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% lipoprotein-deficient serum (LPDS) and containing 75μg/mL of acetylated LDL (acLDL) was added, for 10h.

Cytotoxic MTT assayCytotoxic assays were carried out to evaluate the toxicity of the major broccoli miRNAs, using MTT (Sigma, Madrid, Spain) – a method based on the metabolic reduction of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazol bromide (MTT) by the mitochondrial enzyme succinate-dehydrogenase in a blue colored compound (formazan). The number of live cells is proportional to the amount of formazan produced, which allows the mitochondrial functionality of the treated cells to be determined. After exposing cells to the miRNA mixture, cells were washed with PBS, and the MTT solution was added (0.5mg/mL), for 2h. Supernatants were discarded, ethanol/DMSO (1:1, v/v) was added and absorbance was measured at 547nm.

miRNA analysis by real-time RT-qPCRTreated cells were harvested in QIAzol Lysis Reagent (Qiagen) and total RNA was isolated following the previously described method. Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was performed with 300ng of total RNA, using the mir-X miRNA First-Strand Synthesis kit, following the manufacturer's instructions. miRNA expression was determined by qRT-PCR in 384-well plates on a 7900HT Fast Real-time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems), using FastStart Essential DNA Green Master mix (Roche, Switzerland) and specific miRNA oligonucleotides (Isogen LifeSciences, Utrecht, The Netherland). miRNA expression was normalized with RNU6 as reference. Relative quantification was calculated using the 2ΔΔCt method.18

Cellular cholesterol efflux assayCellular cholesterol efflux assay was performed using microRNA-transfected THP-1-derived macrophages as previously described,19,20 with minor modifications. Briefly, macrophages were labeled with 1.2μCi/mL [1,2-3H(N)]-cholesterol and cholesterol loaded with 50μg/mL acetylated LDL (acLDL) in RPMI medium containing 10% lipoprotein-deficient FBS (density >1.21g/L). After 24h, cells were washed with 0.1% human serum albumin (HSA) in PBS to remove excess 3H-cholesterol and acLDL, and equilibrated in serum-free medium overnight at 37°C. Subsequently, 50μg/mL human HDL (density 1.063–1.21g/L) were added or not to the media and a 4-h incubation was performed. Then, the medium was removed and the 3H-cholesterol present in the medium and in cells was quantified by scintillation counting as disintegrations per minute (dpm). Each condition was run in triplicate. The percentage of efflux to the medium was calculated by the formula: dpm in medium×100/(dpm in medium+dpm in cells). The efflux to HDL-free medium was subtracted from the corresponding values for HDL.

Bioinformatic analysisDe novo prediction of exogenous miRNA targets within the human transcriptome was performed using two approaches. One approach consisted in the use of PITA (probability of interaction by target accessibility) algorithm locally21 as previously described,22 and the second one was performed with the on-line tool psRNATarget.23 Briefly, for PITA analysis, 3′UTR sequences from all human transcripts linked to the RefSeq database were collected and screened for putative interactions with miRNAs from broccoli. To increase the robustness of predictions, targets with an energetic score lower than 10 ΔΔG were retained. The psRNATarget algorithm identifies target transcripts of small RNAs through analyzing complementary matching between sRNA and target using a pre-defined scoring schema and evaluating target site accessibility by calculating unpaired energy (UPE).23 The analysis was performed using the on-line application and utilizing the pre-defined schema V2 for prediction.

Functional enrichment of predicted target genes was performed with GeneCodis424 algorithm using Gene Ontology (GO), Molecular Function (MF), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEEG) pathway and Panther pathways annotation.

Statistical analysisStatistical differences between groups were evaluated using t-tests, comparing the mean of each treatment with that of its control. When appropriate, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, followed by Dunnett's or Bonferroni's post hoc tests. Data are expressed as means±SD, unless indicated otherwise. Statistically significant differences were considered at p≤0.05 (*), p≤0.01 (**), p≤0.001 (***), and p≤0.0001 (****). All analyzes were performed using GraphPad Prism V.9 software.

Results and discussionMajor miRNAs in broccoli. Selection of miRNAs for further analysesIn order to identify major miRNAs present in broccoli inflorescences (edible part) small RNA sequencing was performed as described in “Small RNA sequencing and data analysis” section. A list of the most representative miRNAs of broccoli is shown in Fig. 1.

RNAseq data indicate that miR159 is the most abundant miRNA in broccoli (≈50%), followed by miR166 and miR162. Other major miRNAs include miR319, miR396, miR403 and miR165, among others. This is in line with the findings of other studies on broccoli miRNAs,25,26 although the order of enrichment was not consensual22 and may depend on the variety of broccoli, agroclimatological cultivation conditions or the part(s) of the plant used for analysis. The miR159 family, which is quite conserved in the plant kingdom, is one of the most abundant miRNA families in different edible plants.27 Previous studies in breast cancer models have associated this family with a “cross-kingdom” regulation.15

In order to explore a possible role in reverse cholesterol transport, four major representative broccoli miRNAs were selected (Fig. 1B), some of which had been previously reported to have a possible inter-species regulatory role.15,28 In the case of the miR159 family, two miRNAs – miR159a and miR159b-3p – differing by only one nucleotide in the 3′ region were found to be among the most abundant and were both selected for further analysis.

In vitro gastrointestinal stability evaluationIf a diet-derived miRNA is not able to survive the host's gastrointestinal digestion, changes that it will potentially be able to exert a biological function are null. For this reason, we began by evaluating the stability of selected miRNAs using an in vitro digestion model according to the recommendations of the international consensus paper for a standardized static in vitro digestion method suitable for food.29 This methodology was previously used to study the stability of diet miRNAs in the context of inter-species regulation.25,30,31 Results showed free miRNAs degradation was moderate in the early digestion phases and increased considerably during the intestinal phase (Fig. 2), which is in consonance with results from other studies.31,32 Although the exact mechanisms of diet-miRNA absorption in mammals are not known, it has been suggested that it could occur via stomach pit cells.33 In this sense, certain human polymorphisms in this gene (SIDT1) are associated to differences in the presence of dietary miRNAs in human circulation.34 As gastric survival does not seem to be drastically compromised perhaps miRNAs could be absorbed in the stomach and eventually lead to systemic biological effects. Although statistical significance is not always seen, it seems that the 3′-terminal 2′-O-methylation, characteristic of plant miRNAs,9 confers a certain resistance to degradation compared to non-methylated miRNAs. It has been proposed that factors influencing diet miRNAs stability include their secondary structure and GC content, among others,35 which could help explain why some miRNAs show slightly different survival levels. Thus, form this point onwards analyses were performed using miRNAs with this chemical modification (Fig. 1B).

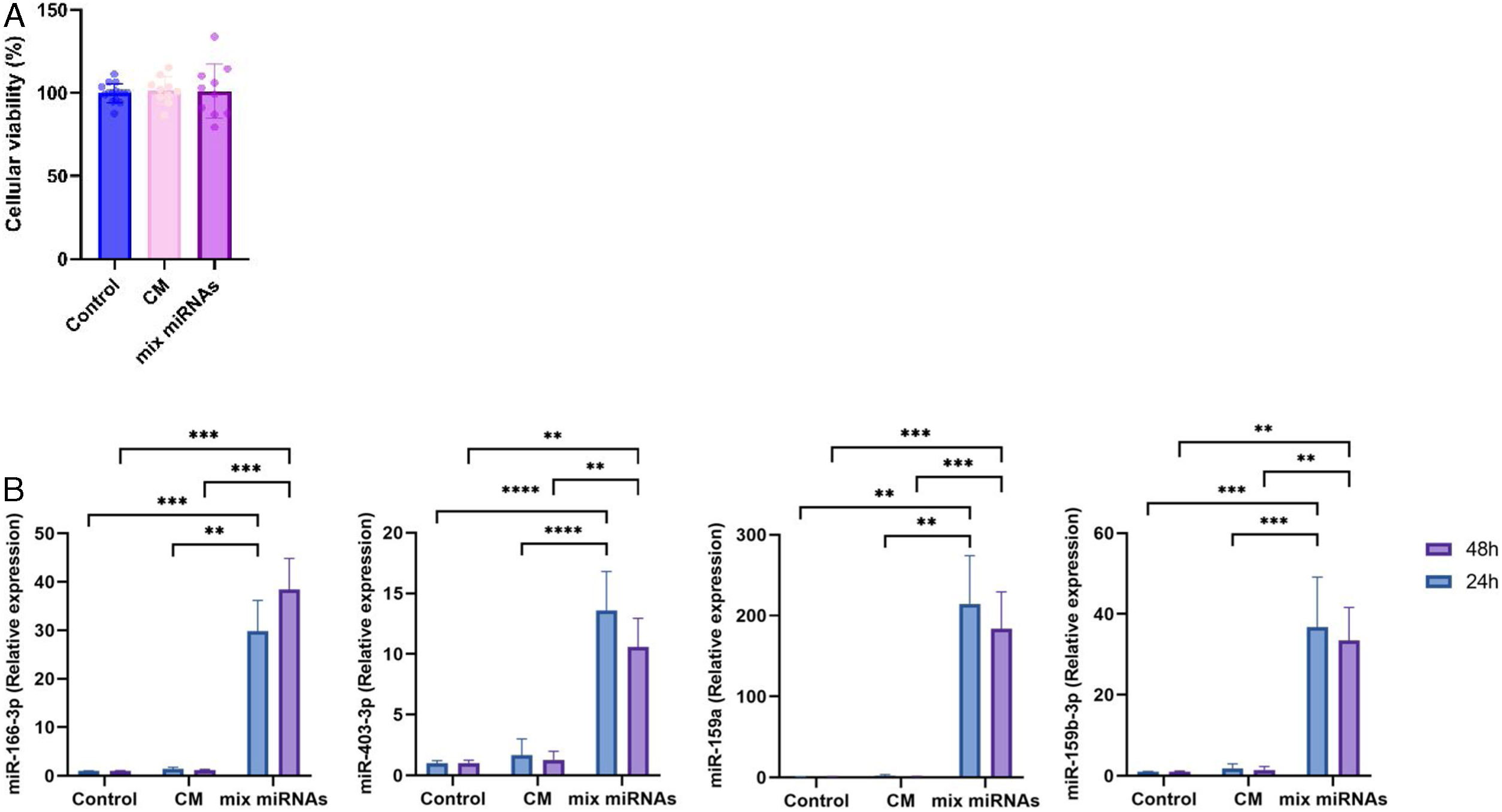

Cellular uptake of broccoli miRNAsTo exert a biological effect, miRNAs must be taken up by the cell and interact with their targets in an adequate concentration to be able to produce relevant effects. For this assay, synthetic miRNAs (mimic or mimetic miRNAs) and their respective controls (mimetic controls, CM) were used. First, a toxicity study was carried out on THP-1 cells differentiated into macrophages. Results showed no changes in cell viability (Fig. 3) in response to treatment with either mimic miRNAs or controls (CM), suggesting that these are not toxic at the tested dose (5nM each).

Cellular viability and uptake of miRNAs. (A) Cellular viability of THP-1 cells exposed to miRNAs or controls (for 24h) assessed by MTT assay. Values are means±SD (n≥3). (B) Cellular uptake of selected broccoli-derived miRNAs. THP-1 cells were exposed with exogenous miRNAs for 24 or 48h. Values are means±SD (n≥3). **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. CM, control mimic.

Next, we evaluated if miRNAs were actually uptaken by cells. To do this, THP-1 cells differentiated into macrophages were exposed to the mix of the four methylated miRNAs or control, for 24 and 48h (Fig. 3B). The levels of intracellular miRNAs increased between 10 and 200 times compared to their basal level, as determined by RT-qPCR. Enrichment levels are similar to previous studies in this model for cholesterol metabolism studies.36

Cholesterol efflux analysis in response to broccoli miRNAsAfter miRNAs were confirmed to be taken up by the in vitro macrophage model used herein, we evaluated whether these miRNAs could influence cellular cholesterol efflux to HDL. Selected broccoli miRNAs were transfected to THP-1 macrophages, which were then exposed to acLDL and radioactive cholesterol. Cholesterol efflux to HDL – a lipoprotein acceptor of cellular cholesterol, which plays a pivotal role in atherosclerotic CVD6 – was then assessed as described above.36 Results showed that the mixture of broccoli miRNAs slightly increased cellular cholesterol efflux to HDL (Fig. 4), suggesting these miRNAs may have a role in cholesterol metabolism or cellular cholesterol handling.

Secretion of endogenous miRNAs, under certain pathological conditions, has been shown to have an effect on cholesterol efflux and atherogenesis.37 Previous studies have evaluated the effects of plant-based diets or food bioactive compounds on the regulation of endogenous miRNAs associated to cholesterol efflux processes.38–40 Although there is scientific interest in developing novel therapies based on plant-derived exogenous miRNAs,11,15 their application to cholesterol efflux processes had not been assessed so far and deserves further investigation.

In silico target analysis of broccoli miRNAs within the human transcriptomeIn silico analysis of the potential target genes of the selected broccoli miRNAs was assessed using two independent miRNA–gene interaction algorithms. For PITA analysis, the full set of human non-redundant and well-annotated 3′ UTR transcript sequences available in the Refseq database41 were used. Results were summarized to gene–level interactions, since each miRNA can interact with multiple alternatively spliced transcripts from the same gene. In the case of PITA, genes targeted by B. oleracea miRNAs are listed in Supplementary Tables S1–S4. The number of unique targets were 555 for miR159a, 534 for miR159b-3p, 217 for miR166a and 62 for miR403. No common miRNA targets were identified (Fig. 5A). As expected, due to their high similarity, miR159a and miR159b-3p share several targets. In total, 824 unique targets were retrieved and subjected to pathway analysis using GeneCodis4.24 The most represented BPs included cell adhesion and phosphorylation (Fig. 5B), while the most represented MFs included calcium ion binding, protein kinase activity, and ATP binding and transferase activity (Fig. 5C). According to KEGG pathway analysis overrepresented genes were associated to choline metabolism and phosphatidylinositol signaling (Fig. 5D). Cadherin signaling and Wnt signaling pathway, among others were the most represented according to Panther pathway analysis (Fig. 5E).

Pathway analysis of potential target of broccoli miRNAs. The analysis is performed by two miRNA–gene interaction algorithms, PITA and psRNATarget algorithm. (A) Venn diagram of common targets of miRNAs analyzed by PITA algorithm, (B) biological process, (C) molecular function, (D) KEGG pathways, and (E) Panther pathways analysis of unique targets of broccoli miRNAs. (F) Venn diagram of common targets of miRNAs analyzed by psRNATarget algorithm. (G) Biological process, (H) molecular function, (I) KEGG pathways, and (J) Panther pathways analysis of unique targets of broccoli miRNAs.

Gene targeted by each B. oleracea miRNAs for psRNATarget analysis are listed in Supplementary Tables S5–S8. The number of unique targets was 121 for miR159a, 125 for miR159b-3p, 72 for miR166a, and 82 for miR403. No common miRNA targets were identified (Fig. 5F). Again, as expected, miR159a and miR159b-3p shared many common targets (86). In total, 306 unique targets were retrieved for pathway analysis. Phosphorylation was the most represented BP (Fig. 5G), while protein kinase activity, protein binding, ATP binding and transferase activity were the most represented MFs (Fig. 5H). Overrepresented KEGG pathway included phosphatidylinositol signaling, hippo signaling or Rap1 signaling (Fig. 5I). Finally, Huntington's disease and the insulin/IGF pathway were the most overrepresented according to Panther's pathway analysis (Fig. 5J).

In terms of miRNA target prediction, in both mammals and plants, there are several algorithms using diverse features to determine the probability of miRNA–gene interaction. These tools can be classified into different categories: sequence-based tools (TargetScan, miRanda, PITA, or PACCMIT-CDS); energy-based tools (PicTar, RNAhybrid, RNAduplex, or microT-CDS); machine learning-based tools (MBSTAR20, MiRTDL21, TarPmiR22, or miRDB23); statistics-based tools (RNA2224); or database-based tools (StarMirDB25).42 Some of these use different types of evidence for target validation for pathway analysis. However, when performing target prediction from one kingdom miRNA (i.e., plant kingdom) within a target of a different kingdom (i.e., mammalian) there is scares information about prediction algorithm. For this reason, we here used two different algorithms (i.e., PITA and psRNATarget). We found that both algorithms retrieved different amounts of targets, while PITA gave 824 unique targets for the four miRNAs analyzed, psRNATarget retrieved 306 unique targets. The reason for the disparity in the target number is unknown. Moreover, among predicted targets of both algorithms, we only found 44 common targets. These results suggest the need of developing novel algorithms to predict the possible targets among different kingdoms. One would expect more common target genes among different algorithms for the same miRNAs. But, in contrast to what happen in mammalian and plants models per se, there no exist validated targets or different types of evidence of validation when performing prediction of plant miRNAs on the human transcriptome.

One of the major differences in miRNAs interaction between mammalians and plants has to do with the degree of complementary. While plant miRNAs recognize fully or nearly complementary binding sites, which are generally located in ORFs, animal miRNAs recognize partially complementary binding sites, which are generally located in 3′ UTRs.43 This is relevant as available algorithms find also targets with high degrees of complementary. Whether these predicted targets are real validated targets is completely unknown. Indeed, in mammals, extensive miRNA-target complementarity can trigger recognition by the ZSWIM8 ubiquitin ligase, resulting in proteasomal turnover of the miRNA-containing complex and miRNA decay.44 Another relevant difference between species is the 3′-O-methylation of plant miRNAs.9 How this methylation actually affects the interaction between plant miRNAs and animal genes is poorly described. In this context, recent data suggest that mammalian miRNAs (i.e., miR-21-5p) could be also methylated at that specific position in certain pathological conditions such as cancer.45 Indeed, compared to non-methylated miR-21-5p, methylated miR-21-5p was found to be more resistant to digestion by 3′→5′ exoribonucleases and had higher affinity to Argonaute-2, which may contribute to its higher stability and stronger inhibition of specific target genes.45 These data reveal that 3′-terminal 2′Ome of mammalian miRNAs could enhance miRNA's stability and function. However, whether this feature of plant miRNA methylation within a mammalian system influences features such as binding, stability or function deserves further investigation.

LimitationsSome limitations of this study are acknowledged. For example, only four miRNAs found in broccoli were selected. Whether other non-selected miRNAs have higher resistance and/or higher biological activity regarding cholesterol efflux remains unknown. A mixture of 5nM of each miRNA was able to exert an in vitro effect on cholesterol efflux. If stomachal absorption was to be discarded and considering the over 90% degradation seen at the end of the in vitro digestion, we would need to ingest, at least, 500nM of each miRNA in order for, theoretically, enterocytes to be exposed to a sufficient amount of these miRNAs. We do not know if this starting concentration of miRNAs can lead to any effects in vivo and this deserves further research. Moreover, having evaluated all four miRNAs together (as a mixture) we are not able to elucidate if the effect seen in cholesterol efflux depends on all four miRNAs being present. We also acknowledge that the statistical differences in cholesterol efflux is mild. Whether, a higher concentration of miRNAs or the use of individual miRNAs would yield better results is unknown and deserves further investigation. Finally, we did not focus on specific miRNA targets, which would require extensive characterization.

Concluding remarksOverall, the in vitro experimental analyses performed here show that broccoli miRNAs: (1) possess a certain degree of resistance to the harsh conditions of the gastrointestinal tract, (2) can be taken up by human-derived macrophages, and (3) play a role in cellular cholesterol efflux. Bioinformatic analysis of the potential target genes of exogenous miRNAs showed an involvement in processes related to phosphorylation (GO), phosphatidylinositol signaling (KEGG pathway), and Wnt signaling and insulin/IGF pathway (Panther pathway), suggesting that some of the health-promoting properties attributed to cruciferous vegetables, might be mediated, at least in part, through miRNA-related mechanisms. Whether the in vitro effects seen here can be reproduced in vivo deserves further investigation.

FundingThis research was funded by Fundación Española de Arterioesclerosis (Beca de Nutrición “Manuel de Oya” 2021 to MCLH). It was also partly funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (RTI2018-098113-B-I00), by the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR (TED2021-130962B-C21) and by ERDF – A way of making Europe (PID2022-143100OB-I00). MCLH is a recipient of a Juan de la Cierva Grant IJC2020-044353-/MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/EU/PRTR. AS-L is supported by a predoctoral fellowship (No. 2021-01-PhD GRANT) from the International Olive Council. CIBEROBN (CB22/03/00068) is an initiative of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain.

Authors’ contributionsMCLH and AD designed the study. MCLH, JTC and AD wrote the paper. MCLH, JTC, AdS-L, LB, GdlP, JG-Z, MA, and AD performed the experiments and/or data collection. LAC and AD conducted RNAseq and bioinformatic analysis. AD, MCLH, EBR, MR-P, and DG-C obtained funding. All authors have read and approved this manuscript.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest associated with this work.