To understand the prevalence of subclinical atherosclerosis (SCA) in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) patients; to explore the correlation between PsA combined with SCA and traditional cardiovascular risk factors and disease activity; to compare the role of Framingham Risk Score (FRS) and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) scores.

MethodsWe included 50 PsA patients who met the CASPAR classification criteria, 50 diabetes patients and 50 healthy people. Clinical data were collected from all patients, minimal disease activity (MDA), disease activity index for psoriatic arthritis (DAPSA), ASCVD, FRS were assessed in patients with PsA, and carotid artery intima–media thickness was measured.

ResultsThe prevalence of SCA in PsA patients was significantly higher than that in healthy controls (44% vs 24%, P<0.05). Smoking, drinking, ASCVD, FRS were the risk factors of PsA with SCA (P<0.05). Psoriasis (PsO) duration, PtGA, VAS and DAPSA were the risk factors for PsA with SCA (P<0.05). FRS and ASCVD scores underestimated SCA risk in PsA patients.

ConclusionCompared with healthy controls, patients with PsA have higher prevalence of SCA. High DAPSA is a risk factor for PsA with SCA. Carotid ultrasound can monitor SCA in patients with PsA, improve stratification of cardiovascular risk.

Conocer la prevalencia de la aterosclerosis subclínica (SCA) en pacientes con artritis psoriásica (PsA); explorar la correlación entre la PsA combinada con la SCA y los factores de riesgo cardiovascular tradicionales y la actividad de la enfermedad; comparar el papel de las puntuaciones de Framingham Risk Score (FRS) y Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD).

MétodosSe incluyeron 50 pacientes con PsA que cumplían los criterios de clasificación CASPAR, 50 pacientes con diabetes y 50 personas sanas. Se recopilaron los datos clínicos de todos los pacientes, se evaluaron la actividad mínima de la enfermedad (MDA), el índice de actividad de la enfermedad para la artritis psoriásica (DAPSA), la ASCVD y la FRS en los pacientes con PsA, y se midió el grosor íntima-media de la arteria carótida.

ResultadosLa prevalencia de la SCA en los pacientes con PsA fue significativamente mayor que en los controles sanos (44 vs. 24%; p<0,05). El tabaquismo, el consumo de alcohol, la ASCVD y la FRS fueron los factores de riesgo de la PsA con SCA (p<0,05). La duración de la psoriasis (PsO), PtGA, VAS y DAPSA fueron los factores de riesgo de la PsA con SCA (p<0,05). Las puntuaciones de FRS y ASCVD subestimaron el riesgo de la SCA en pacientes con PsA.

ConclusionesEn comparación con los controles sanos, los pacientes con PsA tienen mayor prevalencia de SCA. La DAPSA elevada es un factor de riesgo de PsA con SCA. La ecografía carotídea puede monitorizar la parada cardiaca súbita en los pacientes con PsA y mejorar la estratificación del riesgo cardiovascular.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory joint disease associated with psoriatic skin lesions that affects up to 30% of patients with psoriasis (PsO).1 The clinical manifestations of PsA patients vary greatly, and there are many manifestations. Studies have found that the incidence and mortality of cardiovascular diseases in PsA patients are higher than those in general, which is the main cause of death in PsA patients.2 Subclinical atherosclerosis (SCA) is a good substitute for cardiovascular disease and an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.3 Early identification of PsA patients with SCA lesions and early treatment can reduce the risk of death. The combination of SCA in PsA patients may be related to traditional cardiovascular risk factors, or it may be related to the inflammation of PsA disease itself. It was reported that PsA patients with more traditional cardiovascular risk factors showed higher disease activity compared to those with no traditional cardiovascular risk factors.4 Other studies have found that PsA's chronic inflammation increases cardiovascular disease risk independently and/or in concert with traditional cardiovascular risk factors.3

A study found that the increase in carotid intima–media thickness (cIMT) by 0.1mm was associated with the HR of related cardiovascular disease being 1.65.5 EULAR recommends cardiovascular risk scores using the Framingham Risk Score (FRS) and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) to calculate the 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with PsA, but this risk score tends to underestimate the risk of cardiovascular disease in people with PsA.6 Whether cardiovascular risk score can increase PsA and SCA risk needs further study. We aimed to understand the prevalence of SCA in patients with PsA, explore the correlation between PsA with SCA and traditional cardiovascular risk factors and disease activity, and compare the role of cardiovascular risk score FRS, ASCVD, and ultrasound assessment of carotid atherosclerosis in cardiovascular risk stratification in patients with PsA.

MethodsStudy populationFifty patients with CASPAR PsA who were hospitalized in the Rheumatology and Immunology Department of Shanxi Bethune Hospital from March 2021 to February 2022 were included, and 50 patients with diabetes and 50 healthy physical examination subjects who were treated during the same period were included as controls. Patients with malignant tumor, serious chronic disease, chronic infection history, recent infection, pregnancy, and PsA with psychiatric symptoms were excluded. Diabetic patients with target organ damage, abnormal liver and kidney function, a history of coronary artery disease (angina pectoris, stable coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, ischemic heart surgery), a history of cerebrovascular disease (stroke, transient ischemic attack), chronic lung disease (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and a history of psychiatric disorders were excluded. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanxi Bethune Hospital and all signed written informed consent (approval number: YXLL-2022-031).

Data collection and evaluationBlood pressure, smoking history, age, height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) of PsA patients, diabetic patients, and healthy people were collected. Uric acid, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), fasting blood glucose, total cholesterol (TC), high density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL), low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL) and triglyceride (TG) were measured. All PsA patients were evaluated using three clinical measures of disease activity: psoriasis area and severity index (PASI),7 disease activity index for psoriatic arthritis (DAPSA),8 minimal disease activity (MDA),9 cardiovascular risk FRS score,10 and ASCVD score.11 Ultrasound doctors routinely use 5–10MHz linear array probes, and use gray scale imaging to observe bilateral common carotid artery, bulbar carotid artery, and intima, media, and outer wall of proximal carotid artery in transverse section and then longitudinal section. Patients with cIMT ≥1.0mm and/or localized cIMT ≥1.5mm are diagnosed as SCA.12

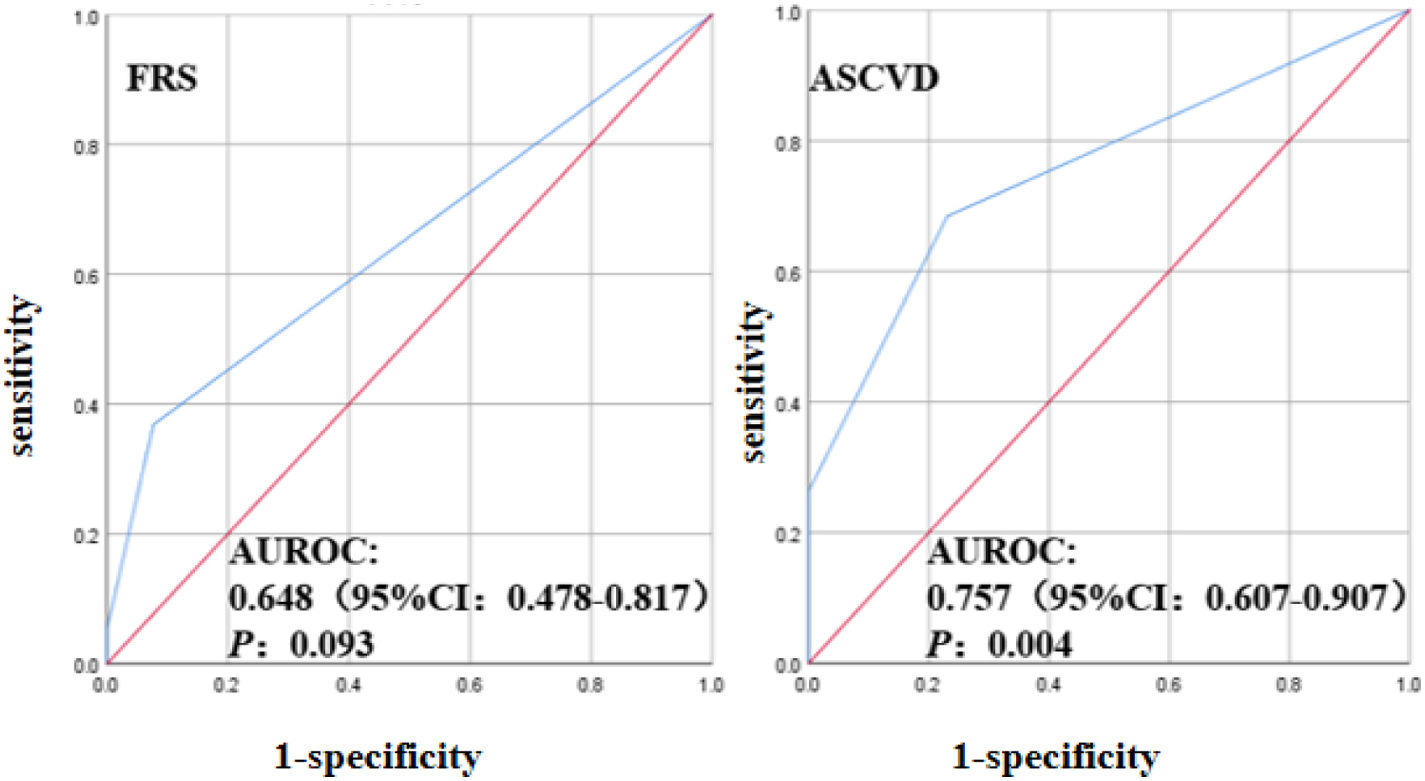

Statistical analysisAll data were analyzed using SPSS26.0 statistical software. For continuous variables, Shapiro–Wilk was first used to test their normality. For continuous variables with normal distribution, mean plus or minus standard deviation (x¯±s) was used for statistical description. Comparison between the two groups was performed by t test. The non-normal distribution was represented by M (P25, P75), and the comparison between the two groups was performed by non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney U test). Categorical variables were statistically described by frequency and percentage (%), and the (2 test was used for statistical analysis. Correlation factors were analyzed by binary logistic regression analysis, P<0.05 was statistically significant. ROC curve was used to evaluate the diagnostic value of ASCVD and FRS cardiovascular risk scores in PsA patients with SCA risk.

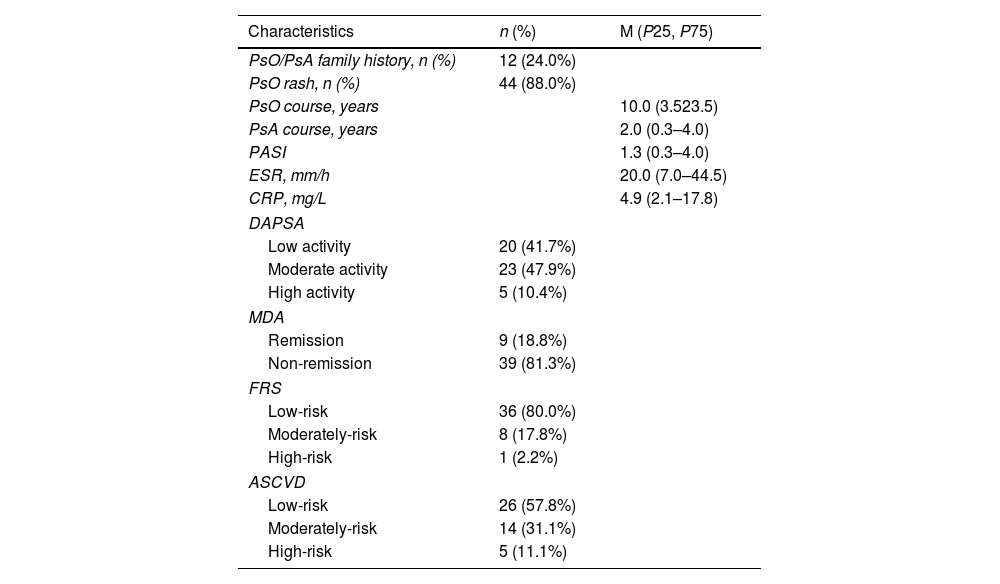

ResultsBaseline characteristicsA total of 50 PsA patients were included, of which 48 met the DAPSA assessment criteria, with 41.7% low activity, 47.9% moderate activity, and 10.4% high activity. Forty-eight cases met the MDA assessment conditions, with remission of 18.8% and non-remission of 81.3%. There were 45/45 patients with PsA who met the FRS/ASCVD calculation conditions, including low-risk 80.0%/57.8%, medium-risk 17.8%/31.10%, and high-risk 2.2%/11.1% (Table 1).

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of PsA patients (n=50).

| Characteristics | n (%) | M (P25, P75) |

|---|---|---|

| PsO/PsA family history, n (%) | 12 (24.0%) | |

| PsO rash, n (%) | 44 (88.0%) | |

| PsO course, years | 10.0 (3.523.5) | |

| PsA course, years | 2.0 (0.3–4.0) | |

| PASI | 1.3 (0.3–4.0) | |

| ESR, mm/h | 20.0 (7.0–44.5) | |

| CRP, mg/L | 4.9 (2.1–17.8) | |

| DAPSA | ||

| Low activity | 20 (41.7%) | |

| Moderate activity | 23 (47.9%) | |

| High activity | 5 (10.4%) | |

| MDA | ||

| Remission | 9 (18.8%) | |

| Non-remission | 39 (81.3%) | |

| FRS | ||

| Low-risk | 36 (80.0%) | |

| Moderately-risk | 8 (17.8%) | |

| High-risk | 1 (2.2%) | |

| ASCVD | ||

| Low-risk | 26 (57.8%) | |

| Moderately-risk | 14 (31.1%) | |

| High-risk | 5 (11.1%) | |

PsA: psoriatic arthritis; PsO: psoriasis; PASI: psoriasis area and severity index; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: C-reactive protein; DAPSA: disease activity index for psoriatic arthritis, low activity (4<DAPSA≤14), moderate activity (14<DAPSA≤28), high activity (DAPSA>28); MDA: minimal disease activity, remission ≥5, non-remission <5; FRS: Framingham Risk Score, FRS >20% high-risk, 10%–20% moderate risk, and <10% low-risk; ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, ASCVD <5% low-risk, 5%–10% medium-risk, ≥10% high-risk.

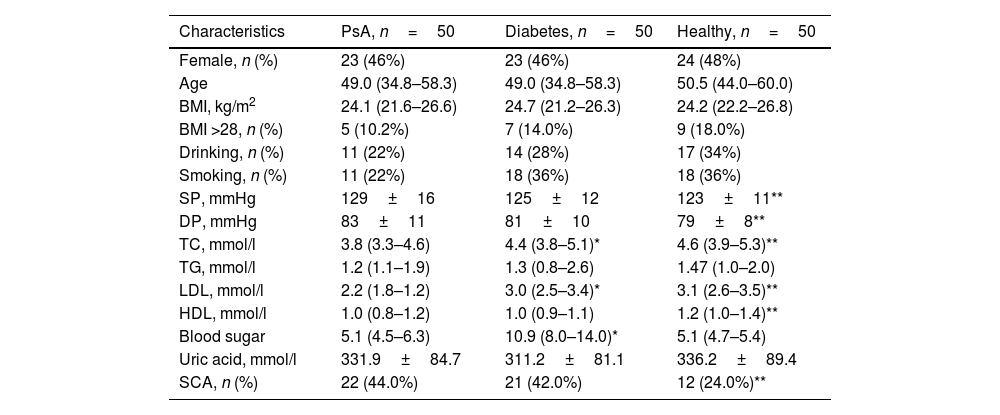

Compared with healthy controls, systolic blood pressure (123±11 vs 129±16, P=0.021) and diastolic blood pressure (79±8 vs 83±11, P=0.021) were significantly higher in PsA patients. Total cholesterol (P=0.000), low-density lipoprotein (P=0.000), high density lipoprotein (P=0.006) were significantly reduced. Compared with diabetic patients, PsA patients had significantly lower total cholesterol (P=0.008), low-density lipoprotein (P=0.000), and blood glucose levels (P=0.000). The incidence of SCA in PsA patients was significantly higher than that in healthy controls (P<0.05), and the difference was statistically significant. The prevalence of SCA in PsA patients was similar to that in diabetes group (P>0.05), with no statistical significance (Table 2).

Comparison of clinical characteristics of PsA, diabetic patients and healthy group.

| Characteristics | PsA, n=50 | Diabetes, n=50 | Healthy, n=50 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 23 (46%) | 23 (46%) | 24 (48%) |

| Age | 49.0 (34.8–58.3) | 49.0 (34.8–58.3) | 50.5 (44.0–60.0) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.1 (21.6–26.6) | 24.7 (21.2–26.3) | 24.2 (22.2–26.8) |

| BMI >28, n (%) | 5 (10.2%) | 7 (14.0%) | 9 (18.0%) |

| Drinking, n (%) | 11 (22%) | 14 (28%) | 17 (34%) |

| Smoking, n (%) | 11 (22%) | 18 (36%) | 18 (36%) |

| SP, mmHg | 129±16 | 125±12 | 123±11** |

| DP, mmHg | 83±11 | 81±10 | 79±8** |

| TC, mmol/l | 3.8 (3.3–4.6) | 4.4 (3.8–5.1)* | 4.6 (3.9–5.3)** |

| TG, mmol/l | 1.2 (1.1–1.9) | 1.3 (0.8–2.6) | 1.47 (1.0–2.0) |

| LDL, mmol/l | 2.2 (1.8–1.2) | 3.0 (2.5–3.4)* | 3.1 (2.6–3.5)** |

| HDL, mmol/l | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4)** |

| Blood sugar | 5.1 (4.5–6.3) | 10.9 (8.0–14.0)* | 5.1 (4.7–5.4) |

| Uric acid, mmol/l | 331.9±84.7 | 311.2±81.1 | 336.2±89.4 |

| SCA, n (%) | 22 (44.0%) | 21 (42.0%) | 12 (24.0%)** |

PsA: psoriatic arthritis; BMI: body mass index; SP: systolic pressure; DP: diastolic pressure; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglyceride; LDL: low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; HDL: high density lipoprotein-cholesterol; SCA: subclinical atherosclerosis.

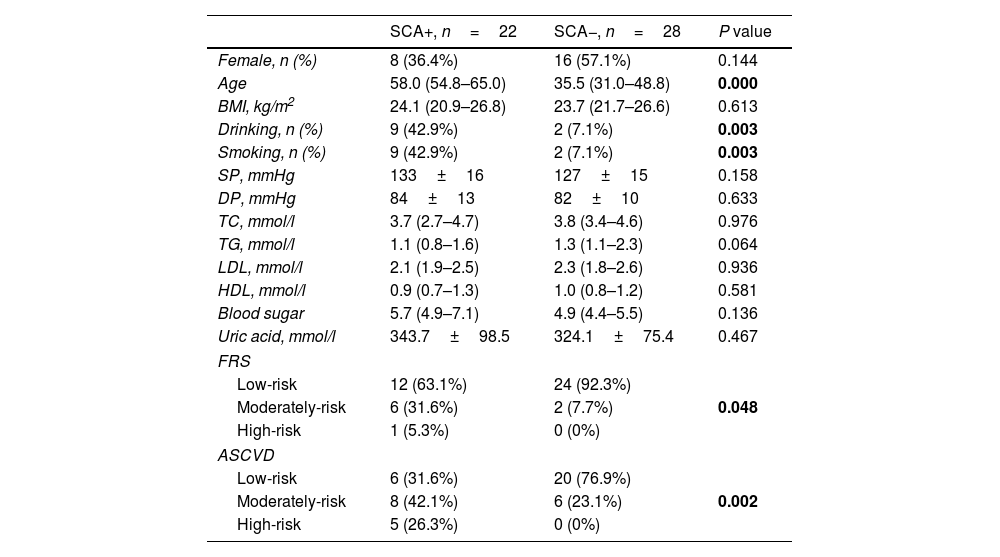

Compared with PsA patients without SCA, PsA patients with SCA had a higher risk of age [35.5 (31.0, 48.8) vs 58.0 (54.8, 65.0), P=0.000], smoking (7.1% vs 42.9%, P=0.003), alcohol consumption (7.1% vs 42.9%, P=0.003) were significantly increased, and the difference was statistically significant. In addition, in PsA patients with SCA, FRS (P=0.002) and ASCVD (P=0.048) were significantly increased, and the differences were statistically significant (Table 3).

Comparison of traditional cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular risk scores of PSA with and without SCA.

| SCA+, n=22 | SCA−, n=28 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 8 (36.4%) | 16 (57.1%) | 0.144 |

| Age | 58.0 (54.8–65.0) | 35.5 (31.0–48.8) | 0.000 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.1 (20.9–26.8) | 23.7 (21.7–26.6) | 0.613 |

| Drinking, n (%) | 9 (42.9%) | 2 (7.1%) | 0.003 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 9 (42.9%) | 2 (7.1%) | 0.003 |

| SP, mmHg | 133±16 | 127±15 | 0.158 |

| DP, mmHg | 84±13 | 82±10 | 0.633 |

| TC, mmol/l | 3.7 (2.7–4.7) | 3.8 (3.4–4.6) | 0.976 |

| TG, mmol/l | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | 1.3 (1.1–2.3) | 0.064 |

| LDL, mmol/l | 2.1 (1.9–2.5) | 2.3 (1.8–2.6) | 0.936 |

| HDL, mmol/l | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.581 |

| Blood sugar | 5.7 (4.9–7.1) | 4.9 (4.4–5.5) | 0.136 |

| Uric acid, mmol/l | 343.7±98.5 | 324.1±75.4 | 0.467 |

| FRS | |||

| Low-risk | 12 (63.1%) | 24 (92.3%) | 0.048 |

| Moderately-risk | 6 (31.6%) | 2 (7.7%) | |

| High-risk | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| ASCVD | |||

| Low-risk | 6 (31.6%) | 20 (76.9%) | 0.002 |

| Moderately-risk | 8 (42.1%) | 6 (23.1%) | |

| High-risk | 5 (26.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

PsA: psoriatic arthritis; BMI: body mass index; SP: systolic pressure; DP: diastolic pressure; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglyceride; LDL: low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; HDL: high density lipoprotein-cholesterol; FRS: Framingham Risk Score, FRS >20% high-risk, 10%–20% moderate risk, <10% low-risk; ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, ASCVD <5% low-risk, 5%–10% medium-risk, ≥10% high-risk.

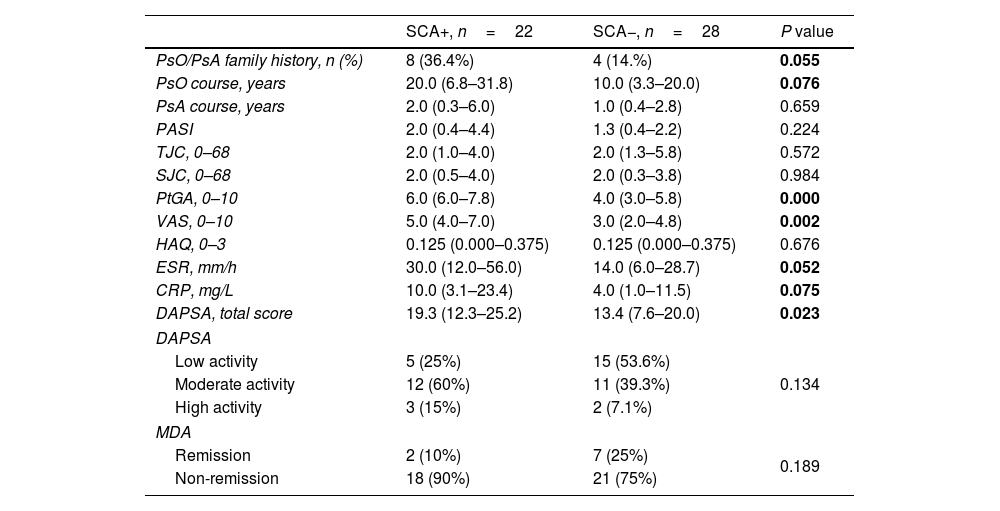

PsO or PsA family history, PsO course, ESR, CRP tended to increase in PsA patients with SCA, but did not reach a statistical difference. Compared with PsA patients without SCA, PsA patients with SCA had higher scores in PtGA [4.0 (3.0, 5.8) vs 6.0 (6.0, 7.8), P=0.000], VAS [3.0 (2.0, 4.8) vs 5.0 (4.0, 7.0), P=0.002], DAPSA [13.4 (7.6, 20.2) vs 19.3 (12.3, 25.2), P=0.023] were significantly increased, and the difference was statistically significant (Table 4).

Comparison of disease characteristics and disease activity of PSA with and without SCA.

| SCA+, n=22 | SCA−, n=28 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PsO/PsA family history, n (%) | 8 (36.4%) | 4 (14.%) | 0.055 |

| PsO course, years | 20.0 (6.8–31.8) | 10.0 (3.3–20.0) | 0.076 |

| PsA course, years | 2.0 (0.3–6.0) | 1.0 (0.4–2.8) | 0.659 |

| PASI | 2.0 (0.4–4.4) | 1.3 (0.4–2.2) | 0.224 |

| TJC, 0–68 | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 2.0 (1.3–5.8) | 0.572 |

| SJC, 0–68 | 2.0 (0.5–4.0) | 2.0 (0.3–3.8) | 0.984 |

| PtGA, 0–10 | 6.0 (6.0–7.8) | 4.0 (3.0–5.8) | 0.000 |

| VAS, 0–10 | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 3.0 (2.0–4.8) | 0.002 |

| HAQ, 0–3 | 0.125 (0.000–0.375) | 0.125 (0.000–0.375) | 0.676 |

| ESR, mm/h | 30.0 (12.0–56.0) | 14.0 (6.0–28.7) | 0.052 |

| CRP, mg/L | 10.0 (3.1–23.4) | 4.0 (1.0–11.5) | 0.075 |

| DAPSA, total score | 19.3 (12.3–25.2) | 13.4 (7.6–20.0) | 0.023 |

| DAPSA | |||

| Low activity | 5 (25%) | 15 (53.6%) | 0.134 |

| Moderate activity | 12 (60%) | 11 (39.3%) | |

| High activity | 3 (15%) | 2 (7.1%) | |

| MDA | |||

| Remission | 2 (10%) | 7 (25%) | 0.189 |

| Non-remission | 18 (90%) | 21 (75%) | |

PsA: psoriatic arthritis; PsO: psoriasis; PASI: psoriasis area and severity index; TJC: tender joint count; SJC: swollen joint count; PtGA: patient's global assessment; VAS: patient pain assessment; HAQ: Health Assessment Questionnaire; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: C-reactive protein; DAPSA: disease activity index for psoriatic arthritis, low activity (4<DAPSA≤14), moderate activity (14<DAPSA≤28), high activity (DAPSA>28); MDA: minimal disease activity, remission ≥5, non-remission <5.

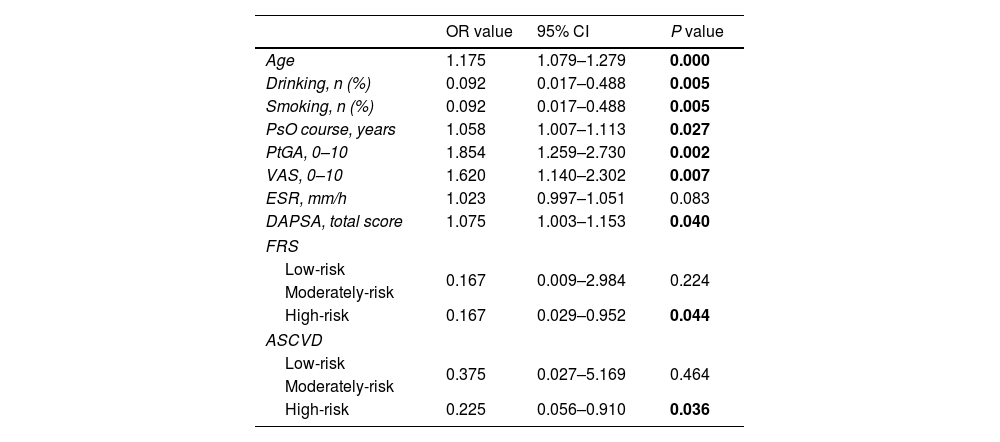

Multivariate logistic regression model analysis was performed on the indicators of statistical difference between PsA patients with SCA and those without SCA (age, smoking, alcohol consumption, PsO duration, PtGA, VAS, ESR, DAPSA, FRS, ASCVD). The results indicated that age (OR=1.175, 95% CI 1.079–1.279, P=0.000), alcohol/smoking (OR=0.092, 95% CI 0.017–0.488, P=0.005), PsO duration (OR=1.058, 95% CI 1.007–1.113, P=0.027), PtGA (OR=1.854, 95% CI 1.259–2.730, P=0.002), VAS (OR=1.620, 95% CI 1.140–2.302, P=0.007), DAPSA (OR=1.075, 95% CI 1.003–1.153, P=0.040), medium-high risk FRS (OR=0.167, 95% CI 0.029–0.952, P=0.044), medium-high risk ASCVD (OR=0.225, 95% CI 0.056–0.910, P=0.036) is a risk factor for SCA in patients with PsA, and these patients are more likely to develop SCA (Table 5).

Risk factors associated with PSA combined with SCA.

| OR value | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.175 | 1.079–1.279 | 0.000 |

| Drinking, n (%) | 0.092 | 0.017–0.488 | 0.005 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 0.092 | 0.017–0.488 | 0.005 |

| PsO course, years | 1.058 | 1.007–1.113 | 0.027 |

| PtGA, 0–10 | 1.854 | 1.259–2.730 | 0.002 |

| VAS, 0–10 | 1.620 | 1.140–2.302 | 0.007 |

| ESR, mm/h | 1.023 | 0.997–1.051 | 0.083 |

| DAPSA, total score | 1.075 | 1.003–1.153 | 0.040 |

| FRS | |||

| Low-risk | 0.167 | 0.009–2.984 | 0.224 |

| Moderately-risk | |||

| High-risk | 0.167 | 0.029–0.952 | 0.044 |

| ASCVD | |||

| Low-risk | 0.375 | 0.027–5.169 | 0.464 |

| Moderately-risk | |||

| High-risk | 0.225 | 0.056–0.910 | 0.036 |

PsA: psoriatic arthritis; PsO: psoriasis; SCA: subclinical atherosclerosis; PtGA: patient's global assessment; VAS: patient pain assessment; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; DAPSA: disease activity index for psoriatic arthritis; FRS: Framingham Risk Score, FRS >20% high-risk, 10%–20% moderate risk, <10% low-risk; ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, ASCVD <5% low-risk, 5%–10% medium-risk, ≥10% high-risk.

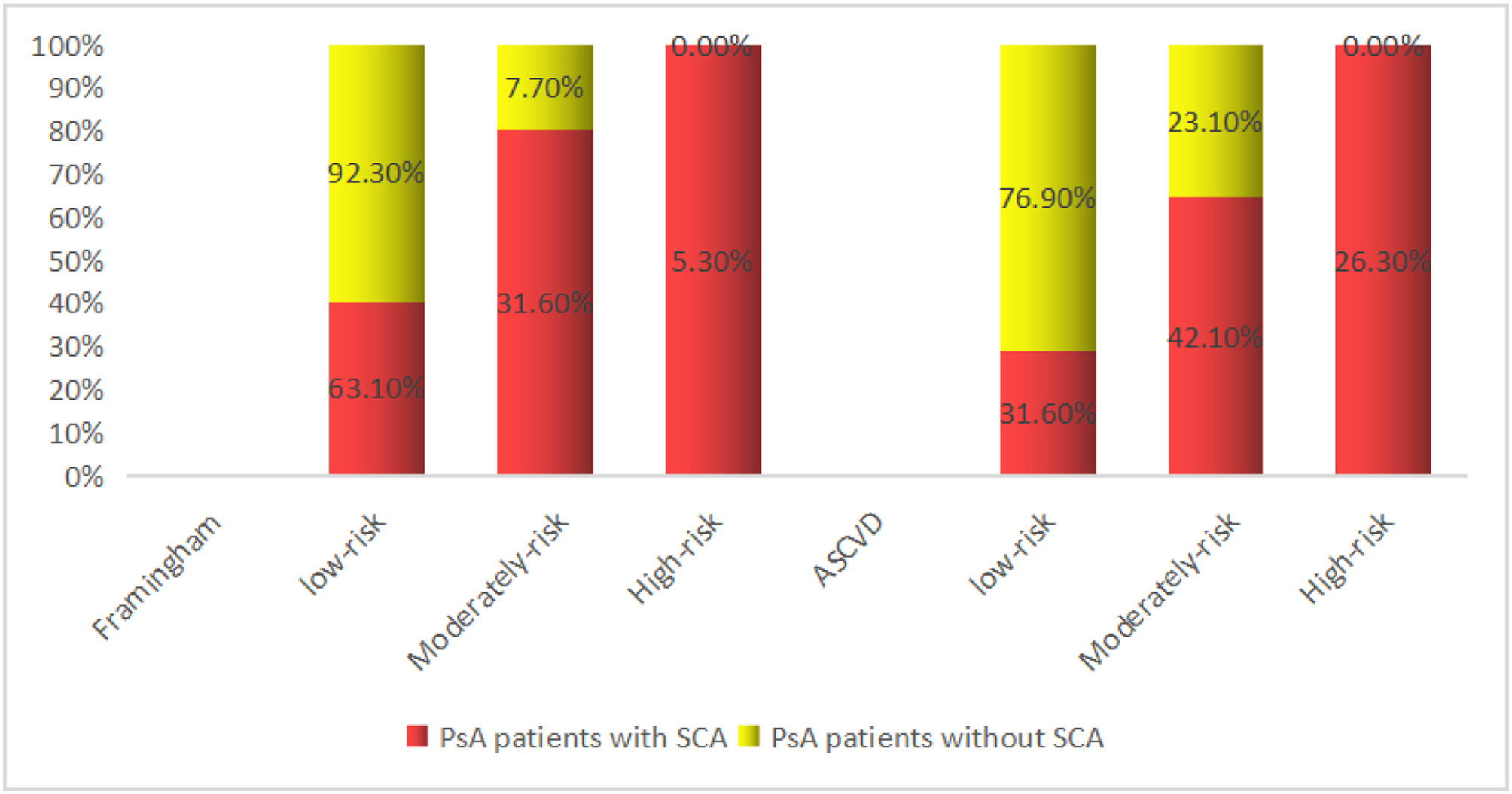

FRS and ASCVD evaluated the risk of SCA in PsA patients with AUROC: 0.648 (95% CI: 0.4788–0.817, P=0.093), AUROC: 0.757 (95% CI: 0.757 (0.607–0.907), P=0.004), indicating that cardiovascular risk scores FRS and ASCVD underestimated the SCA risk of patients with PsA, possibly because FRS and ASCVD did not take into account the effect of PsA inflammatory factors, and therefore underestimated the actual risk (Fig. 1). SCA in patients with PsA is a surrogate marker for cardiovascular disease, implying a high-risk of future cardiovascular events with PsA.3 In the FRS scores of PsA patients, 63.1% in the low-risk group and 31.6% in the medium-risk group were reclassified as the ultrasound-based high-risk group. In the ASCVD scores of patients with PsA, 31.6% of patients in the low-risk group and 42.1% in the medium-risk group were reclassified into the ultrasound-based high-risk group, which may be because disease activity in patients with PsA affected the cardiovascular risk reclassification based on carotid artery ultrasound (Fig. 2).

PsA is a chronic inflammatory joint disease associated with PsO lesions and is associated with increased mortality from comorbid cardiovascular disease.13 The presence of carotid atherosclerosis in patients with PsA is associated with an increased risk of future cardiovascular events.14 In the absence of routine risk factors or obvious cardiovascular disease, the impairment of vascular endothelial function in PsA was similar to that in RA patients.15 Abnormal increases in cIMT were observed in PsA patients without cardiovascular events or classical cardiovascular disease risk factors compared to matched controls.16 Our study found that 22% of PsA patients had SCA, significantly higher than the control group. Our study highlights the importance of cardiovascular prevention strategies for PsA with early diagnosis of atherosclerosis.

Traditional cardiovascular risk factors may contribute to the increased risk of SCA in patients with PsA. A 2016 study found that people with PsA had elevated levels of traditional cardiovascular risk factors compared to the general population.17 A prospective cohort study showed that traditional cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic syndrome were more common in patients with PsA than in patients with other inflammatory arthritis.18 These traditional cardiovascular risk factors may contribute to the rapid progression of cIMT or an increased prevalence of atherosclerotic plaques. Shen et al.19 found that PsA patients with SCA were older, had higher systolic blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein, and cholesterol, and had significantly higher clinical cardiovascular risk scores, including FRS and ASCVD. In our study, we found that patients with PsA and SCA were older, smoked and drank more, and had significantly higher ASCVD and FRS scores. Evaluation of traditional, modifiable cardiovascular risk factors should therefore be encouraged in all patients with PsA. In addition to traditional risk factors, inflammation in PsA patients themselves is also involved in the onset of SCA. Studies have shown that increased cardiovascular risk in patients with PsO is associated with systemic inflammation of skin and joint diseases, in addition to a high prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.20 A study of cardiovascular risk in patients with PsA found that the risk may depend on the course of the disease itself and the burden of inflammation, and that FRS and ASCVD scores may underestimate the true cardiovascular risk in these patients.21 Our results support this view. Because we used a cardiovascular risk score to assess SCA risk in patients with PsA, we found that the risk was underestimated, possibly because the cardiovascular risk score did not take into account inflammatory factors in patients with PsA. There is now evidence that disease activity, as determined by the DAPSA score, is responsible for accelerated atherosclerosis in patients with PsA.22 Our study shows that DAPSA and PsO disease duration is a key factor in accelerating the development of atherosclerosis in patients with PsA, underscoring the critical role of disease activity in SCA, which may also be a major factor leading to the reclassification of cardiovascular risk in patients with PsA after carotid artery ultrasound assessment. A cross-sectional study of 140 patients with PsA found that patients with PsA exhibited fewer SCA symptoms than those with DAPSA remission from MDA.23 This fact highlights active management of the disease to reduce the burden of inflammation, which can not only prevent disability, but also prevent the risk of cardiovascular events.

Carotid ultrasound is safe and reproducible and is an assessment tool that can quantify the burden of SCA and determine the risk of cardiovascular disease. The presence of SCA is considered a strong predictor of future cardiovascular events.24 FRS and ASCVD are the most widely used cardiovascular risk scores and are primarily assessed based on traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Ernste et al.,25 and Eder et al.,26 suggested that FRS underestimated the risk of PsA cardiovascular events and SCA. In this study, FRS and ASCVD cardiovascular risk scores were performed on patients with PsA, and it was found that at least one-third of patients in the low-risk and medium-risk groups were diagnosed with SCA, while all patients in the high-risk group were diagnosed with SCA, indicating that the cardiovascular risk score may underestimate the cardiovascular risk of patients with PsA, and cervical angiography can improve risk stratification. Because the cardiovascular risk score does not take into account systemic inflammation in patients with PsA, cardiovascular risk is underdiagnosed and treated, potentially increasing cardiovascular burden. Similar conditions have been observed in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus27 and RA.2,28 Therefore, it is of great importance to find non-invasive ways to identify high-risk cardiovascular risk in patients with PsA. Our study recommends the use of carotid ultrasound to assess cardiovascular risk in patients with PsA, which is inexpensive, reproducible, and precise in diagnosis. Similarly, the control of PsA disease activities should be emphasized. Studies have found that TNF-α inhibitors can delay the progression of SCA and reduce artery stiffness while treating PsA inflammation, and reduce cardiovascular risk.29

The main limitations of this study are the cross-sectional design, so we could not conclude the precise role of SCA in predicting the true risk of cardiovascular events in patients with PsA, in addition to the small sample size, which needs to be enlarged and followed up over time.

In conclusion, this study supports evidence of increased SCA in PsA patients and the importance of screening these patients for cardiovascular disease. The association of traditional risk factors and PsA disease activity with SCA was highlighted. The cardiovascular risk score underestimated SCA risk and demonstrated the effectiveness of carotid ultrasound as a screening method for cardiovascular disease risk in patients with PsA.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ contributionsZhoulan Zheng and Qianru Liu were involved in the study design, literature search, data acquisition, data analysis, statistical analysis, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing; Zhenan Zhang was involved in the study design, literature search, data acquisition; Qianyu Guo and Liyun Zhang were involved in the study design, statistical analysis, manuscript revision; Gailian Zhang was involved in the study design, statistical analysis, manuscript revision, manuscript review and is corresponding author is responsible for the integrity of the work as a whole from inception to published article.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.