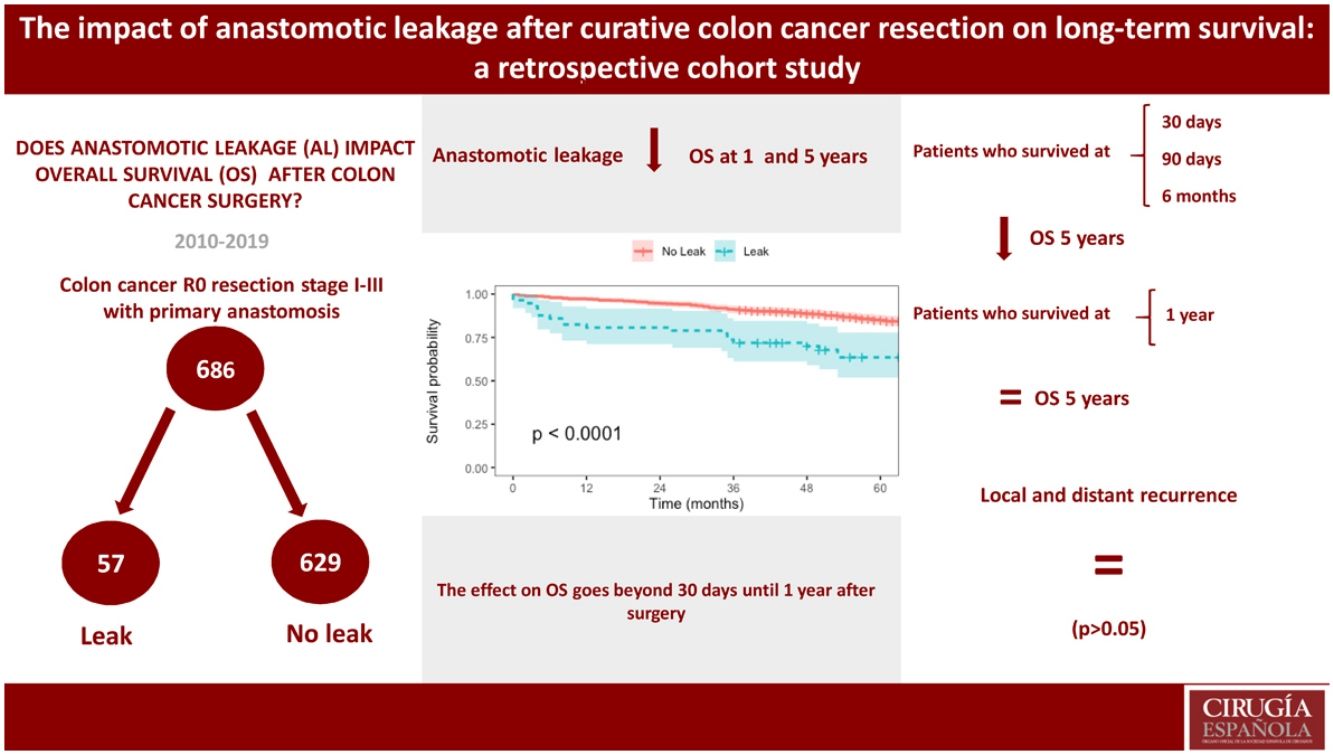

Anastomotic leakage (AL) is one of the most feared postoperative complications in colon cancer surgery due to an association with increased morbidity and mortality, although its impact on long-term survival is not consensual. The aim of this study was to investigate the influence of AL on long-term survival of patients undergoing curative colon cancer resection.

MethodsA single-centre retrospective cohort study was designed. Clinical records of all consecutive patients undergoing surgery at our institution between 01/01/2010 and 12/31/2019 were reviewed. Survival analysis was performed by Kaplan–Meier method to estimate overall and conditional survival and Cox regression to search for risk factors impacting survival.

ResultsA total of 2351 patients submitted to colorectal surgery were screened for eligibility, of which 686 with colon cancer were included. AL occurred in 57 patients (8,3%) and was associated with higher postoperative morbidity and mortality, length of stay and early readmissions (P < 0,05). Overall survival was inferior in the leakage group (Hazard Ratio 2,08 [1,02–4,24]). Conditional overall survival at 30, 90 days and 6 months was also inferior in the leakage group (P < 0,05), but not at 1 year. Risk factors independently associated with reduced overall survival included AL occurrence, higher ASA classification and delayed/missed adjuvant chemotherapy. AL did not impact local and distant recurrence (P > 0,05).

ConclusionAL has a negative impact on survival. Its effect is more pronounced on short-term mortality. AL does not appear to be associated with disease progression.

La fuga anastomótica (FA) es una complicación postoperatoria temida en la cirugía del cáncer de colon por asociación con mayor morbimortalidad, aunque su impacto en la supervivencia a largo plazo no es consensuado. Nuestro objetivo fue investigar el efecto de la FA en la supervivencia a largo plazo de pacientes sometidos a resección curativa del cáncer de colon.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio de cohorte retrospectivo unicéntrico de pacientes consecutivos intervenidos quirúrgicamente entre 01/01/2010 y el 31/12/2019. El análisis de supervivencia se realizó por el método de Kaplan-Meier para evaluar la supervivencia global (SG) y condicional y una regresión de Cox para evaluar los factores de riesgo con efecto en la supervivencia.

ResultadosDe 2351 pacientes sometidos a cirugía colorrectal, se incluyeron 686 con cáncer de colon. FA afectó 57 pacientes (8,3%) y se asoció con mayor morbimortalidad postoperatoria, duración de estancia hospitalaria y reingresos (P < 0,05). La SG fue inferior en el grupo de fuga (Hazard Ratio 2,08 [1,02–4,24]). La SG condicional a los 30, 90 días y 6 meses fue inferior en el grupo de fugas (P < 0,05), pero no a 1 año. Los factores de riesgo que se asociaron con SG reducida incluyeron la FA, clasificación ASA más alta y quimioterapia adyuvante retrasada/perdida. FA no afectó la recurrencia local y distante (P > 0.05).

ConclusionesFA tiene un impacto negativo en la supervivencia, con efecto más pronunciado sobre la mortalidad a corto plazo, pero no es asociado con la progresión de la enfermedad oncológica.

It remains unclear if anastomotic leakage after colon cancer surgery has a negative impact on long-term survival. Overall survival is reduced after this event, but patients surviving one year after surgery have the same long-term prognosis than patients without AL.

IntroductionColorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in Europe, with an increasing incidence over the last decades.1,2 The treatment of colon cancer is multimodal and includes both systemic and surgical/endoscopic therapies, with surgery playing a key role to achieve cure. One of surgery’s most frequent complications is anastomotic leakage (AL), which can be defined as a communication between the intra and extra-luminal compartments due to a loss of integrity in the anastomotic tissue wall after its surgical construction, as proposed by the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer (ISREC).3

The incidence of AL varies with the type of colonic resection and anastomosis performed, but also with the definition used.3,4 It has been reported as ranging from 1,5%–12,6%.5–12

AL is one dreadful complication of colorectal surgery, leading to an increase in postoperative morbidity,9,13 length of stay,9,14,15 postoperative mortality 6,8,13 and to the delay/missing of adjuvant therapies.9,16 Despite its clear influence on short-term outcomes, there is no consensus that it represents an independent prognostic factor on long-term cancer survival.5–12

In rectal cancer surgery, AL is associated with an increase in local recurrence, but its impact on long-term survival is not yet clear.14,16 In the case of colon cancer, it appears that AL worsens long-term survival, but further studies are needed to confirm it.5–12

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of AL on long-term survival of colon cancer patients, report its short-term outcomes and to identify independent factors associated with this event.

MethodsStudy design and patient selectionA single-centre retrospective cohort study was designed. All consecutive patients operated between January 1st, 2010, and December 31st, 2019, were assessed for eligibility.

Inclusion criteria were patients over 18 years old with a first-time diagnosis of colon cancer, undergoing planned R0 colonic resection without rectal involvement, and having a primary anastomosis without a protective stoma.

Patients with Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) Stage IV at the time of surgery, other concurrent malignant neoplasm and with a personal history of malignancy (except for cured non-melanoma skin neoplasms and well-differentiated thyroid neoplasms) were excluded.

The study is reported according to the STROBE guidelines.17

Data collection, variables, and definitionsAll sociodemographic and clinical previously collected data were validated by at least two members of the research team working together in the process of reviewing each patient’s record. Clinical data included pre-, intra-, and postoperative variables.

AL was defined as proposed by ISREC,3 adapted to colon surgery. The integration of its severity and the resources used to treat it were used to classify AL into 3 grades: no active therapeutic intervention (grade A), no surgical re-intervention (grade B), and requiring surgical re-intervention (grade C).

Pathologic tumour invasion (pT) and number of metastatic lymph nodes (pN) were reviewed to assign a pTNM stage according to the 8th edition of the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours.18

The administration of chemotherapy was considered on adequate timing when it started up to 8 weeks after surgery.19

Follow-up was performed according to the institutional protocol (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Outcome measuresLong-term measures were selected to address the primary outcome: overall survival and conditional overall survival. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from surgery to death by any cause. Conditional overall survival (OSC) includes the analysis of OS limited to patients who meet a certain condition. The conditions chosen for this study were to have survived at least 30 days (OSC 30 days), 90 days (OSC 90 days), 6 months (OSC 6 months), and 1 year (OSC 1 year) after surgery. The follow-up period was considered between surgery and death.

Local recurrence (LR) was defined as clinical, radiologic, and/or pathologic evidence of locoregional relapse. Distant recurrence (DR) was defined as clinical, radiologic, and/or pathologic evidence of tumour spread to distant organs. The follow-up period was between surgery and recurrence. The follow-up period was closed on December 31st, 2023.

Secondary outcomes included short-term measures, such as postoperative morbidity,20 re-intervention rate, early mortality (at 30 and 90 days), length of stay (from surgery to hospital discharge), early readmissions (up to 30 days after hospital discharge), and first-year mortality (at 6 months and 1 year). Independent factors associated with anastomotic leakage were also evaluated.

Statistical analysisThe duration of follow-up was estimated using reverse Kaplan–Meier approach.

Comparison between groups with and without anastomotic leakage was done using Fisher’s exact test, whenever applicable, or Chi-squared test for categorical variables, and Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to investigate independent factors associated with AL. In the final multivariable model, all variables with a P-value <0,2 on the univariable model analysis as well as those considered of clinical interest were included. Goodness-of-fit was evaluated using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test and Cox & Snell R2.

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate OS, OSC, LR, and DR, and survival curves were compared by log-rank test (Mantel–Cox). Independent factors associated with OS were evaluated by a Cox proportional hazards model. The explanatory variables were sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI),21 American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System (ASA classification),22 pTNM stage, adjuvant chemotherapy compliance and occurrence of AL. Age was not included due to its strong influence on the CCI. Goodness-of-fit was evaluated using Chi-square test and Log-likelihood.

A two-tailed P valued <0,05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA) version 26.0, and R version 4.2.0.23

EthicsThe local Ethics Committee approved the study and gave an exemption from obtaining Informed Consent. Patients’ personal data were managed as confidential and in compliance with European General Data Protection Regulation.24

ResultsFrom 01/01/2010 to 12/31/2019, 2351 colorectal surgeries were performed, including 1256 colonic resections, of which 999 had a first-time diagnosis of colon cancer. After applying eligibility criteria, 686 patients (68,7%) were selected for analysis (Supplementary Fig. S2).

The median follow-up was 79,0 months (95% CI, 69,0–8,3).

There were no missing data in the reported variables.

Patient characteristicsMedian age was 69 years (IQR, 61–76), 14,0% of patients were ≥80 years old and 47,2% were ≥70 years old. Three hundred and sixty-six patients were male (53,0%).

Data regarding pre-, intra-, and postoperative variables are summarized in Table 1.

Characteristics of patients submitted to curative resection of colon cancer, overall and comparison of patients with (AL) and without (No AL) anastomotic leakage.

| Overall (n = 686) | No AL (n = 629) | AL (n = 57) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| Median [IQR] | 69 [61–76] | 68 [60–76] | 71 [65–79] | 0,015* | |

| <80 years | 86,0% | 546 (86,8%) | 44 (77,2%) | ||

| ≥80 years | 14,0% | 83 (13,2%) | 13 (22,8%) | 0,069 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 320 (47,0%) | 301 (47,8%) | 19 (33,3%) | 0,038* | |

| Male | 366 (53,0%) | 328 (52,1%) | 38 (66,7%) | ||

| Body Mass Index | |||||

| Median [IQR] | 26,6 [23,9–29,7] | 26,6 [23,9–29,7] | 25,8 (23,6–29,4) | 0,379 | |

| <30 kg/m2 | 76,8% | 484 (76,9%) | 45 (78,9%) | ||

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 23,2% | 145 (23,1%) | 12 (21,1%) | 0,869 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |||||

| 0–3 | 458 (66,8%) | 429 (68,2%) | 29 (50,9%) | 0,012* | |

| ≥4 | 228 (33,2%) | 200 (31,8%) | 28 (49,1%) | ||

| ASA classification | |||||

| I–II | 516 (75,2%) | 476 (75,7%) | 40 (70,2%) | 0,341 | |

| III–IV | 170 (24,8%) | 153 (24,3%) | 17 (29,8%) | ||

| Colonic side | |||||

| Right colon | 319 (46,5%) | 296 (47,1%) | 23 (40,4%) | 0,406 | |

| Left colon | 367 (53,5%) | 333 (52,9%) | 34 (59,6%) | ||

| Surgical procedure | |||||

| Right hemicolectomy | 298 (43,4%) | 279 (44,4%) | 19 (33,3%) | 0,015* | |

| Left hemicolectomy | 81 (11,8%) | 74 (11,8%) | 7 (12,3%) | ||

| Resection of sigmoid/rectosigmoid junction | 264 (38,5%) | 242 (38,5%) | 22 (38,6%) | ||

| Total or subtotal colectomy | 43 (6,3%) | 34 (5,4%) | 9 (15,8%) | ||

| Surgical approach | |||||

| Minimally invasive | 198 (28,9%) | 191 (30,4%) | 7 (12,3%) | 0,003* | |

| Open | 488 (71,1%) | 438 (69,6%) | 50 (87,7%) | ||

| pTNM stage | |||||

| I–II | 464 (67,6%) | 426 (67,7%) | 38 (66,6%) | 0,883 | |

| III | 222 (32,4%) | 203 (32,3%) | 19 (33,3%) | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (n = 235) | |||||

| Adequate timing (≤8 weeks) | 153 (65,1%) | 144 (67,0%) | 9 (45,0%) | 0,083 | |

| Delayed or not performed | 82 (34,9%) | 71 (33,0%) | 11 (55,0%) | ||

| Length of stay* | |||||

| Median [IQR] | 5 (4–7) | 4 (4–6) | 14 (6–21) | <0,001* | |

| Early readmissions* | 48 (6,9%) | 31 (4,9%) | 17 (29,8%) | <0,001* | |

| Mortality* | |||||

| 30-day | 6 (0,9%) | 4 (0,6%) | 2 (3,5%) | 0,082 | |

| 90-day | 11 (1,6%) | 7 (1,1%) | 4 (7,0%) | 0,009* | |

| 6-months | 21 (3,0%) | 13 (2,1%) | 8 (14,0%) | <0,001* | |

| 1-year | 28 (4,1%) | 18 (2,9%) | 10 (17,5%) | <0,001* | |

IQR — interquartile range.

Of the 235 patients with a multidisciplinary team’s decision for adjuvant chemotherapy, 153 (65,1%) started it on time, while 82 (34,9%) had its start delayed or missed it. Of the latter 82 patients, 47 (57,3%) did not start chemotherapy on time for logistical reasons, 20 (24,4%) did not perform it due to advanced age or comorbidities, 12 (14,6%) due to postoperative complications, and 3 (3,7%) refused further treatment.

Morbidity and mortalityMedian number of surgical procedures per year was 67 (IQR, 59–76). Ninety patients (13,1%) had a Clavien-Dindo complication ≥3a.24 The rate of unplanned re-interventions was 11.2%, being AL and evisceration its main indications. The incidence of AL was 8,3% (n = 57).

Mortality was 0,9% at 30 days, 1,6% at 90 days, 3,1% at 6 months, and 4,1% at 1 year.

Anastomotic leakage and associated factorsAL was diagnosed most frequently by imaging (70,2%), while 29,8% were only confirmed intra-operatively. According to AL treatment, 8 patients (14,0%) were classified as ISREC’s grade B and 49 (86,0%) as ISREC’s grade C. No grade A was identified.

The distribution of preoperative clinical variables, short-term outcomes, and timely performance of chemotherapy in the two groups is summarized in Table 1. There was a higher proportion of old and male patients, CCI ≥ 4, total or subtotal colectomies, open surgery, and pT3–4 in the group of patients with AL. The AL group had also a longer length of stay, a higher rate of early readmissions and mortality.

Multiple logistic regression analysis identified depth of invasion pT3–4 (OR 2,18 [1,04–4,57]), performance of total or subtotal colectomy (OR 5,25 [2,05–13,44]) and open approach (OR 2,8 [1,2–6,5]) as independent associated factors to AL (Table 2).

Multiple logistic regression of independent factors associated with the occurrence of anastomotic leakage after surgery.

| OR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <80 years | REF | |

| ≥80 years | 1,28 (0,56–2,93) | 0,562 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | REF | |

| Male | 1,71 (0,94–3,09) | 0,078 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ||

| 0–3 | REF | |

| ≥4 | 1,91 (0,95–3,82) | 0,069 |

| Surgical procedure* | ||

| Right hemicolectomy | REF | |

| Left hemicolectomy | 1,22 (0,48–3,10) | 0,671 |

| Sigmoidectomy/resection of rectosigmoid junction | 1,39 (0,72–2,68) | 0,321 |

| Total or subtotal colectomy* | 5,25 (2,05–13,44)* | 0,001* |

| Surgical approach* | ||

| Minimally invasive | REF | |

| Open* | 2,83 (1,24–6,46)* | 0,013* |

| pT* | ||

| pT1–2 | REF | |

| pT3–4* | 2,18 (1,04–4,57)* | 0,039* |

| pTNM stage | ||

| I–II | REF | |

| III | 0,98 (0,52–1,82) | 0,937 |

Model’s Hosmer–Lemeshow test 0,572, in final step; Cox & Snell R2 0,049.

Variables excluded in the final step model: Body Mass Index (P = 0,863), ASA classification (P = 0,783), and colonic side (P = 0,867).

OR — odds ratio; 95% CI — 95% confidence interval; REF — reference category.

There were no patients lost to follow-up. Overall survival at 1 year was 95,9% (95% CI, 94,3–97,3) and at 5 years, 83,2% (95% CI, 80,3–86,2).

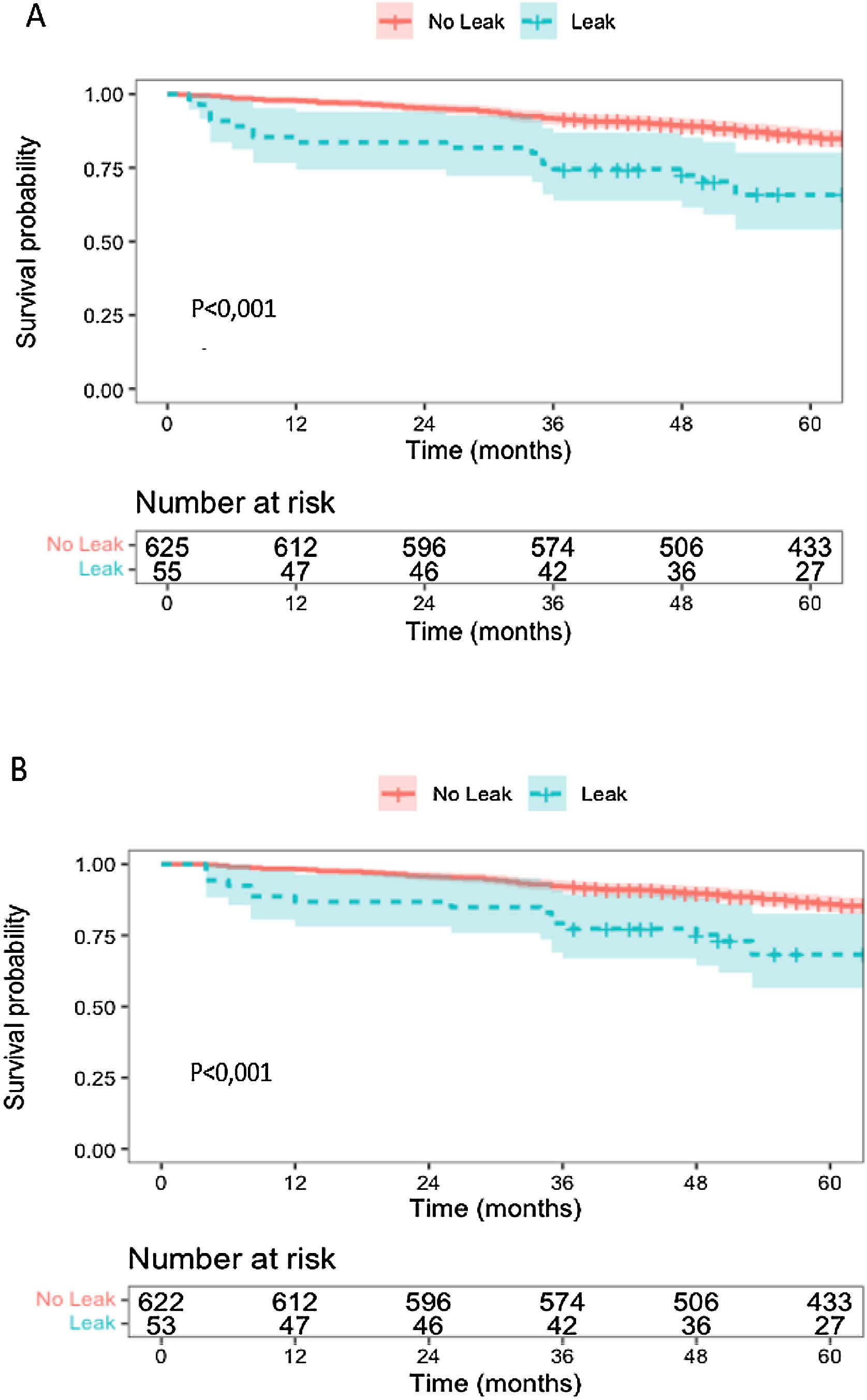

Patients with AL had lower overall survival at 1 year, 80,7% (95% CI, 71,1–91,6) vs 97,1% (95% CI, 95,8–98,5), and at 5 years, 63,5% (95% CI, 51,8–77,8) vs 85,0% (95% CI, 82,2–87,9) (Fig. 1).

In the group of patients with AL, conditional overall survival for those who lived beyond 30 days after surgery (OSC 30 days) was lower at 1 year, 83,6% (95% CI, 74,4–94,0) vs 97,8% (95% CI, 96,6–98,9), and at 5 years, 65,7% (95% CI, 54,0–80,1) vs 85,6% (95% CI, 82,8–88,5) (Fig. 2). Conditional overall survival for those who lived beyond 90 days after surgery (OSC 90 days) was also lower at 1 year, 86,8% (95% CI, 78,1–96,4) vs 98,2% (95% CI, 97,2–99,3), and at 5 years, 68,3% (95% CI, 56,5–82,6) vs 86,0% (95% CI, 83,2–88,8) (Fig. 2). For those who lived beyond 6 months there was also a difference in survival in patients suffering AL (OSC 6 months at 1 year – AL: 93,9% [95% CI, 87,4–100] vs without AL: 99,2% [95% CI, 98,5–99,9] and OSC 6 months at 5 years – AL: 73,9% [95% CI, 62,1–87,9] vs without AL: 86,8% [95% CI, 84,1–89,6]). For those who lived 1 year after surgery (OSC 1 year at 5 years AL: 77,0% [95% CI, 65,3–90,8] vs without AL: 87,5% [95% CI, 84,9–90,3]) there was no difference in survival.

RecurrenceLocal recurrence occurred in 11 patients, 1 in the group with AL and 10 in the group without AL (5-year LR: 2,1% [95% CI, 0–6,2] vs 1,7% [95% CI, 0,5–2,6]). Distant recurrence occurred in 85 patients, 4 in the group with AL and 81 in the group without AL (5-year DR: 9,3% [95% CI, 0,1–18,6] vs 12,8% [95% CI, 10,1–15,4]) (Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4).

Survival and associated factorsCox regression analysis showed that ASA classification III–IV (HR 2,21 [1,26–3,86]), anastomotic leakage (HR 2,08 [1,02–4,24]) and delayed/missed chemotherapy (HR 1,66 [1,02–2,69]) were independently associated with lower overall survival (Table 3).

Cox proportional hazards model of independent factors influencing overall survival.

| HR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | REF | |

| Male | 0,78 (0,48–1,26) | 0,313 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ||

| 0–3 | REF | |

| ≥4 | 1,28 (0,71–2,32) | 0,409 |

| ASA classification* | ||

| Grade I–II | REF | |

| Grade III–IV* | 2,21 (1,26–3,86) * | 0,005* |

| Anastomotic leakage* | ||

| No | REF | |

| Yes* | 2.08 (1.02–4,24) * | 0,043* |

| pTNM stage | ||

| I–II | REF | |

| III | 0,76 (0,30–1,94) | 0,566 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy* | ||

| Adequate timing | REF | |

| Delayed or not performed* | 1,66 (1,02–2,69)* | 0,041* |

Model’s Chi-square test for all variables P < 0,001; Log-Likelihood 685,59.

HR — Hazard Ratio; 95% CI — 95% confidence interval.

Anastomotic leakage is one of the most feared complications of colon cancer surgery, due to its impact on postoperative morbidity and mortality. This study, which reports the routine practice of colon cancer treatment in an oncological dedicated centre, found a total of 57 anastomotic leakages (8,3%) in a group of 686 patients undergoing curative resection of colon cancer in stages I–III. The occurrence of AL was associated with a reduction in overall survival in patients with colon cancer, with mortality being higher in the first year after surgery.

This cohort is one of the largest single-centre series reported in literature and has a very long follow-up period (median = 79,0 months). Unlike other studies, it was decided to exclude patients with a personal history of malignancy and those with a concurrent malignant neoplasm other than colon cancer, seeking to avoid bias in the assessment of long-term survival. The integrity of the study data was excellent and there were no missing values.

The incidence of AL in this cohort (8.3%) seems to be high when compared to other published series. However, this study included a group of patients with AL (n = 8) whose treatment did not required surgery (ISREC’s grade B), a group that is usually not included in studies that focus on this topic.

In the assessment of independent factors associated with AL, this study identified depth of invasion (pT3–4) as well as subtotal/total colectomy, both factors in agreement with the results of Stephensen et al.15 Regarding surgical approach, open surgery was also associated with an increase in AL, as described in recent reports,13 however we must recognize a selection bias in our series, since the most advanced cases were operated through a laparotomy.

Considering survival analysis, the study identified a negative impact of AL on survival after curative colon cancer resection. This deleterious effect was confirmed by the lower overall survival in AL patients, even when trying to eliminate early mortality with conditional overall survival at 30, 90 days and 6 months, like in other reports.8,9,11 The Cox proportional hazards model confirmed the preponderant role of AL in survival. It is important to recognize that this increase in early mortality goes beyond 6 months and continues until the end of the first year.

The reasons for decreased survival related to AL remain unclear. The leakage event may have an adverse impact on the biological course of oncological disease, either because it leads to delay or missing of adjuvant therapy,9 or because of its reduced effectiveness in patients to whom adjuvant therapy was given on adequate timing.25–28 Disease recurrence could justify a decrease in survival, however, in our series there was no difference between groups either in local or distant recurrence, as reported in previous studies focused on colon cancer.5,7,8 The septic process associated with AL may have an important role in survival beyond the early postoperative period, which could extend to one year after surgery. On one hand, unresolved inflammation can lead to frailty and decompensation of previous comorbidities. On the other side, frail patients are more prone to anastomotic leakage, as corroborated by our data, and may have a lower baseline life expectancy.

The present study has some limitations. Although this is a large single-centre retrospective series, the number of patients is smaller than population-based studies,9,12 reducing robustness of analysis performed and restricting the number of variables that can be included in the developed models. Potential differences in the definition, diagnosis and treatment of AL may represent an additional limitation, as it makes comparison with other studies difficult. The analysis of the administration of adjuvant therapy is complex, and the number of cycles as well as the administered doses were not contemplated in our analysis. Additionally, the number of patients over 80 years old was higher in AL group and it is common practice not to perform adjuvant chemotherapy in these patients. Furthermore, there was a high proportion of patients with delayed adjuvant treatment, which may impact long-term survival in this series. The models developed to investigate independent factors associated with anastomotic leakage as well as those associated with overall survival in our series were not validated in a different setting. It would be interesting to extend a study of this nature to other centres, maintaining the same eligibility criteria and variable definitions to try to increase analyses’ robustness.

In conclusion, the survival analysis performed showed a negative effect of AL on long-term outcomes, either by estimating its impact in overall survival or by identifying it as an independent prognostic factor in patients undergoing curative colon cancer resection. This effect is more pronounced on short-term mortality. The occurrence of AL does not appear to be associated with disease progression.

FundingNo funding requested.

Conflicts of interestThis study did not involve any funding and there are no conflicts of interest to report.

This study used data collected from patients treated our centre. The reporting and interpretation of data are the sole responsibility of the authors.