In their article published in the British Medical Journal, Sackett et al.1 formally defined the concept of evidence-based medicine (EBM) as the conscientious and judicious use of current best scientific evidence in the care of individual patients. EBM is a method of working in professional practice that involves integrating clinical experience and the unique values and circumstances of patients with the best available scientific evidence.

Integrating the latter point into professional practice is a major challenge for the physician in general and the surgeon in particular. The rapid advancement of scientific knowledge means that a large number of scientific papers are published each year. For example, in the Surgery category of the Journal Citation Reports there are 213 journals indexed in the year 2022, which contain more than 40,000 citable items. The amount of information available is enormous even if one only wanted to consult clinical trials (the highest level of evidence within empirical studies) in a highly specialised area.

There are other difficulties to add to this extension and rapid updating of the scientific literature. On the one hand, the methodological rigour of the studies conducted is not always optimal, many of them have a high risk of bias in their conclusions. On the other hand, the variability in methodologies, samples, and research contexts leads to contradictory results in the same area of knowledge. Finally, in most cases, the professional lacks the methodological knowledge and sufficient time to review, filter, contrast, and select the most appropriate empirical evidence to meet their knowledge needs.2

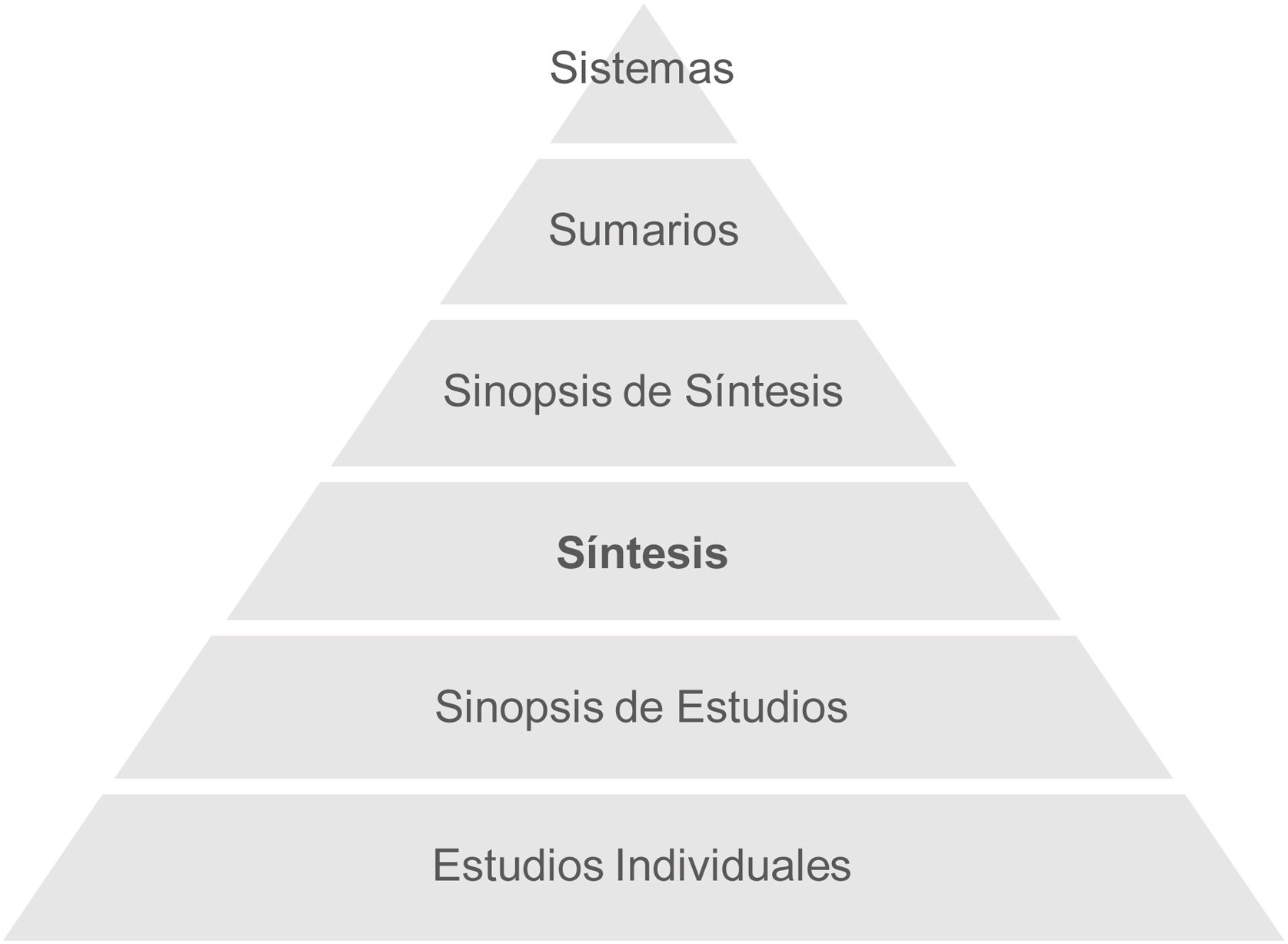

Protocols and clinical practice guidelines are the current solution in medical and surgical practice, which, in an ideal scenario, would be integrated into computerised decision-making systems. However, as we will see below, these are at the apex of a pyramid built on the synthesis and screening of scientific findings obtained in different fields of research. In 2009, DiCenso et al.3 proposed the latest version of the Haynes pyramid model to guide the search and selection of scientific evidence for clinical decision making (Fig. 1).

Haynes 6S pyramid. Studies: empirical studies, provide unfiltered scientific evidence. Synopsis of studies: methodological quality assessments or critical appraisals of individual studies. Synthesis: systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Synopsis of synthesis: methodological quality assessments or critical appraisals of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Summaries: clinical practice guidelines that provide evidence-based recommendations. Systems: computerised systems that integrate the best available evidence for decision making.

Syntheses of the literature, the third block of the pyramid, are best exemplified by systematic reviews and meta-analyses. In both cases, multiple studies on the same research question are searched for and compiled, relevant information about methodology, participants, and results is extracted, the risk of bias of the included studies is assessed, and an objective summary of the evidence is presented, all using systematic and replicable procedures.4 In addition, meta-analysis allows the quantitative integration of the results, providing greater statistical power, and making it possible to analyse the influence of study characteristics on the heterogeneity of the results.5

As we have seen, the systematic review and meta-analysis are the fundamental links in the process of applying scientific evidence to professional practice. They are generally considered to be the highest level of evidence in most classifications for making recommendations in clinical guidelines. Examples are the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) (CEBM)6 or the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN).7

Undoubtedly, in addition to the synthesis of evidence, filtering evidence according to the probability of risk of bias in its conclusions is the key value of the systematic review and meta-analysis. So much so that there is growing interest in the development of increasingly rigorous tools to assess the risk of bias and adapted to different research designs.8

These factors underline the need for the medical professional to understand, use, and master the interpretation of systematic reviews and meta-analysis in their clinical decision making.