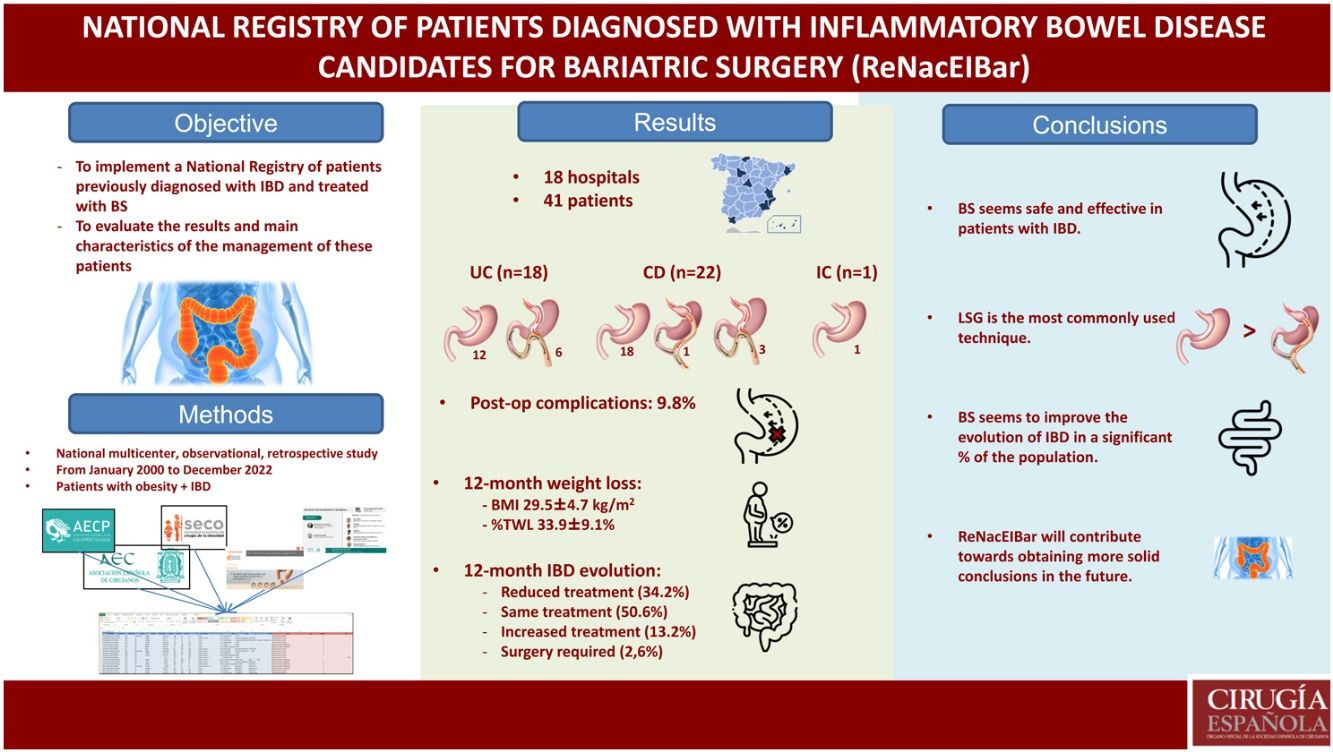

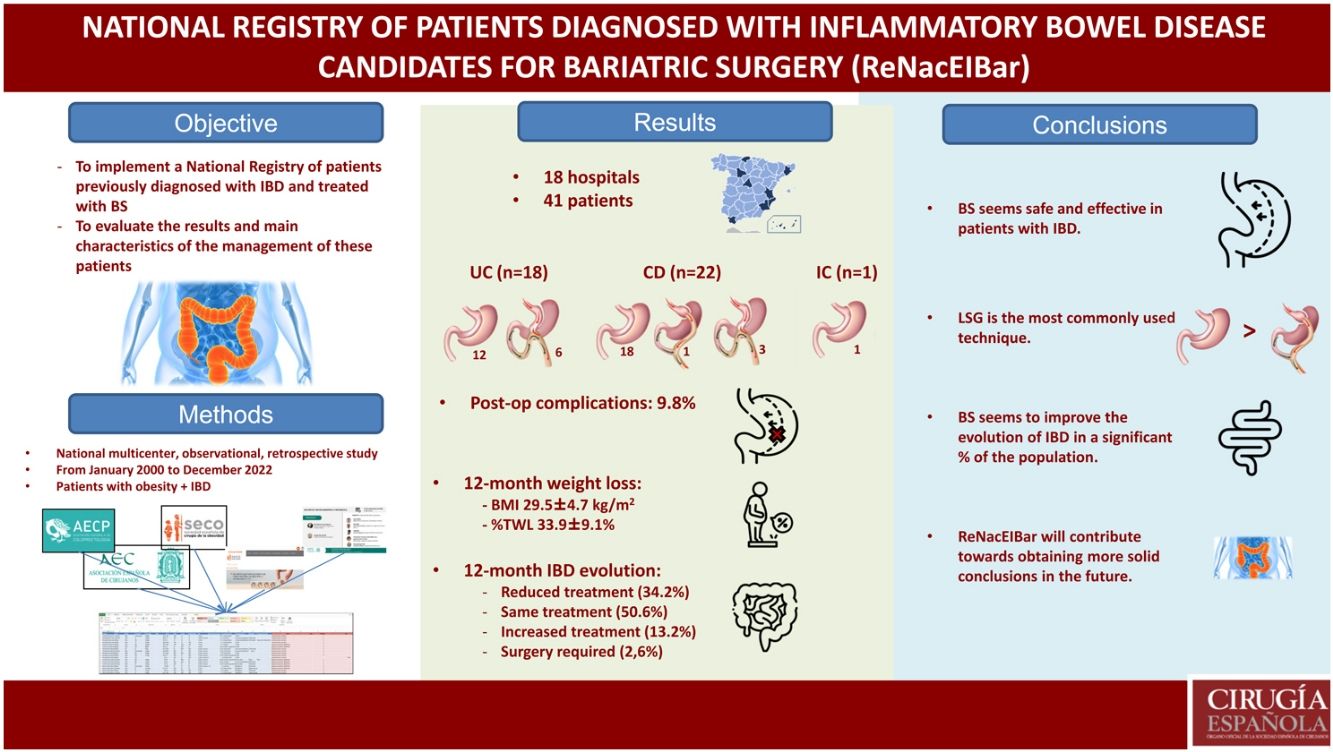

Our aim is to carry out a national registry of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) who underwent bariatric surgery, as well as evaluate the results and management of this type of patients in the usual clinical practice.

MethodsNational multicentric observational retrospective study, including patients, previously diagnosed with IBD who underwent bariatric surgery from January 2000 to December 2022.

ResultsForty-one patients have been included: 43,9% previously diagnosed with ulcerative colitis, 57,3% Crohn's disease, and an indeterminate colitis (2,4%). The preoperative BMI was 45.8 ± 6,1 kg/m2. Among the bariatric surgeries, 31 (75,6%) sleeve gastrectomy, 1 (2,4%) gastric bypass and 9 (22%) one anastomosis gastric have been carried out. During the postoperative period, 9.8% complications have been recorded. BMI was 29,5 ± 4,7 kg/m2 and percent total weight lost was 33,9 ± 9,1% at 12 months.

ConclusionsBariatric surgery in patients with inflammatory bowel disease can be considered safe and effective.

El objetivo principal es realizar un Registro Nacional de pacientes diagnosticados de enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) que son sometidos a cirugía bariátrica, así como evaluar los resultados y aspectos fundamentales del manejo de este tipo de pacientes en la práctica clínica habitual.

MetodologíaEstudio retrospectivo observacional multicéntrico nacional, en el que se incluyen pacientes diagnosticados previamente de EII, que hayan sido intervenidos de cirugía bariátrica desde enero de 2000 hasta diciembre de 2022.

ResultadosSe han incluido un total de 41 pacientes: 43,9% diagnosticados previamente de colitis ulcerosa, 53,7% de enfermedad de Crohn, y una colitis indeterminada (2,4%). El IMC preoperatorio ha sido de 45,8 ± 6,1 kg/m2. Se han realizado 31 (75,6%) gastrectomías verticales, 1 (2,4%) Bypass gástrico y 9 (22%) Bypass gástrico de una anastomosis. Se han registrado un 9,8% de complicaciones. A los 12 meses, el IMC medio fue de 29,5 ± 4,7 kg/m2, presentando un %PTP de 33,9 ± 9,1%.

ConclusionesLa cirugía bariátrica en pacientes previamente diagnosticados de EII se puede considerar eficaz en cuanto a pérdida de peso, y segura en relación con un porcentaje bajo de complicaciones.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) presents with a characteristic state of chronic inflammation of the digestive tract. Although the exact etiology is unknown, it is likely the result of a combination of genetic, immunological and environmental factors. Its incidence has been on the rise in recent decades, especially in developed and developing countries.1,2 In patients with established IBD, several factors can significantly affect the natural course of the disease,3 and obesity has been shown to be a determining factor in its evolution. This influence of obesity has stirred interest in the medical community, as we have witnessed in several studies published in recent years, but the varying methodologies and small sample sizes are limitations.4 Even so, these studies do coincide in demonstrating how obesity in patients with IBD could lead to different scenarios: greater need for hospital admission, greater perianal involvement, impaired response to medical treatment, earlier need for surgery, more postoperative complications, and lower quality of life.5,6 In turn, obesity presents a pattern of systemic chronic proinflammatory, and there may be common links between the two diseases.

Despite the fact that obesity has traditionally been considered an unusual condition in IBD, the parallel increase in prevalence in both entities, which is more pronounced in Crohn’s disease (CD) than in ulcerative colitis (UC), leads us to consider common pathophysiological mechanisms.7,8 Consequently, obesity has become one more piece of the intricate puzzle that is the pathophysiology and management of IBD. These mechanisms include the role of adipose tissue, which is a metabolically and hormonally active organ with an overproduction of numerous cytokines that mediate a proinflammatory effect, exacerbating the activity in autoimmune diseases, including IBD. The increased expression of adiponectin in mesenteric tissue (creeping fat) has been found in patients with active CD and has even been directly associated with the formation of strictures in these patients. In the same manner, “dysbiosis” or altered intestinal signaling and consequent changes in the hormonal response, together with the use of corticosteroid-type medication, will contribute to weight gain.9

The treatment of obesity could play an important role in the management of these patients, in which bariatric surgery could be likewise essential.10–12 When faced with obese patients with IBD, surgical teams have been reluctant to perform any surgery not directly related to their underlying disease, such as bariatric procedures, expecting a high risk of short- and long-term complications.13 Contradictorily, the latest reviews conclude that bariatric surgery appears to be feasible and safe in carefully selected IBD patients when performed in the context of a multidisciplinary team. However, most are retrospective series, with a small sample size and limited information on postoperative complications in the intermediate and long term.14–18 In patients with IBD, the effect of weight loss on the evolution of the disease is also an interesting factor that could lead us to consider these procedures as one more option in the therapeutic arsenal of these patients.19

Currently there is a lack of consensus and standardization on many features of the management of these patients with associated obesity, due to both the limitations of the evidence and the lack of knowledge of current clinical practice.

The main objective of this study is to implement a National Registry of patients previously diagnosed with IBD who are treated with bariatric surgery, as well as to evaluate the fundamental characteristics and results of the management of patients with morbid obesity and inflammatory bowel disease in clinical practice.

MethodsThe protocol for this study has been prepared in accordance with the guidelines established by the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) statement for observational studies.

This is a national multicenter observational retrospective study, in which no invasive interventions were performed beyond standard clinical practice.

Patient selectionPatients were included from various Spanish hospitals who agreed to collaborate with the registry, after prior approval by the corresponding local Ethics Committee.

The case series consisted of patients diagnosed with IBD at the participating hospitals who met the following inclusion criteria: patients over 18 years of age, with a documented clinical history of IBD, who had undergone a bariatric surgical procedure during the study period (January 2000–December 2022). Being an observational study, the sample size was determined by the number of surgical patients during the study period and the total number of participating centers.

VariablesThe variables have been agreed upon by an expert team of bariatric surgeons and coloproctologists in order to provide an overview of the usual management of these patients. Preoperative parameters included age, sex, weight, body mass index (BMI), and obesity-related comorbidities (hypertension [HTN], type 2 diabetes [DM], dyslipidemia, and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome [OSAS]) at the time of surgery. The IBD-specific characteristics included the location according to the Montreal classification,20 the duration of the disease, previous intestinal surgeries, and the type of medication required (classified into 4 large groups: salicylates, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and biological). The feasibility and safety of the procedure was evaluated based on postoperative complications. These were divided into those related to IBD or the bariatric procedure, either intraoperatively or postoperatively. Postoperative complications were broken down into short-term complications (<30 days) and long-term complications (>30 days), including the need for readmission or reoperation.

Postoperative changes in IBD were evaluated according to the treatment required in the last available patient record: no treatment, stable, increase/reduction of previous treatment, and further surgeries associated with IBD.

Data for weight, BMI, percentage of total weight lost (%TWL) and percentage of excess BMI lost (%EBMIL) within 12 months were obtained from the postoperative follow-up.

Data collectionWe designed a data registration form (ReNacEIBar) to register all the study variables, which was sent to the head researcher at each medical center once their interest in participating had been confirmed.

For further diffusion of the study, we contacted the Spanish Association of Surgeons (Asociación Española de Cirujanos, AEC), the Spanish Society of Bariatric Surgery (Sociedad Española de Cirugía Bariátrica, SECO), as well as the Spanish Association of Coloproctology (Asociación Española de Coloproctología, AECP). After their review and approval of the project, it was sent to all members in order to obtain the widest and most representative sample possible nationwide. In addition, the project was part of the co-working program on the official SECO page so that any interested party could be included. In September 2021, the project was presented during an AEC webinar (sharing ideas and projects) to encourage the participation of more hospitals.

To conduct the study, information was collected from electronic hospital records and routine examinations performed during admission as well as visits to the Colorectal and Bariatric Surgery Unit. All information collected by the local research teams was registered in the database specially designed for the study, while maintaining patient anonymity.

StatisticsFor the descriptive study, the quantitative variables have been expressed with their means and standard deviation (SD). The qualitative variables were expressed according to number (n) and fraction of the total (%). The comparison of continuous variables was performed using Student’s t tests for independent data and the Mann–Whitney U test for variables that do not follow normal distribution. For categorical variables, the Chi-square tests or Fisher's exact test were used. The statistical analysis was obtained with SPSS® version 22 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL), and a P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

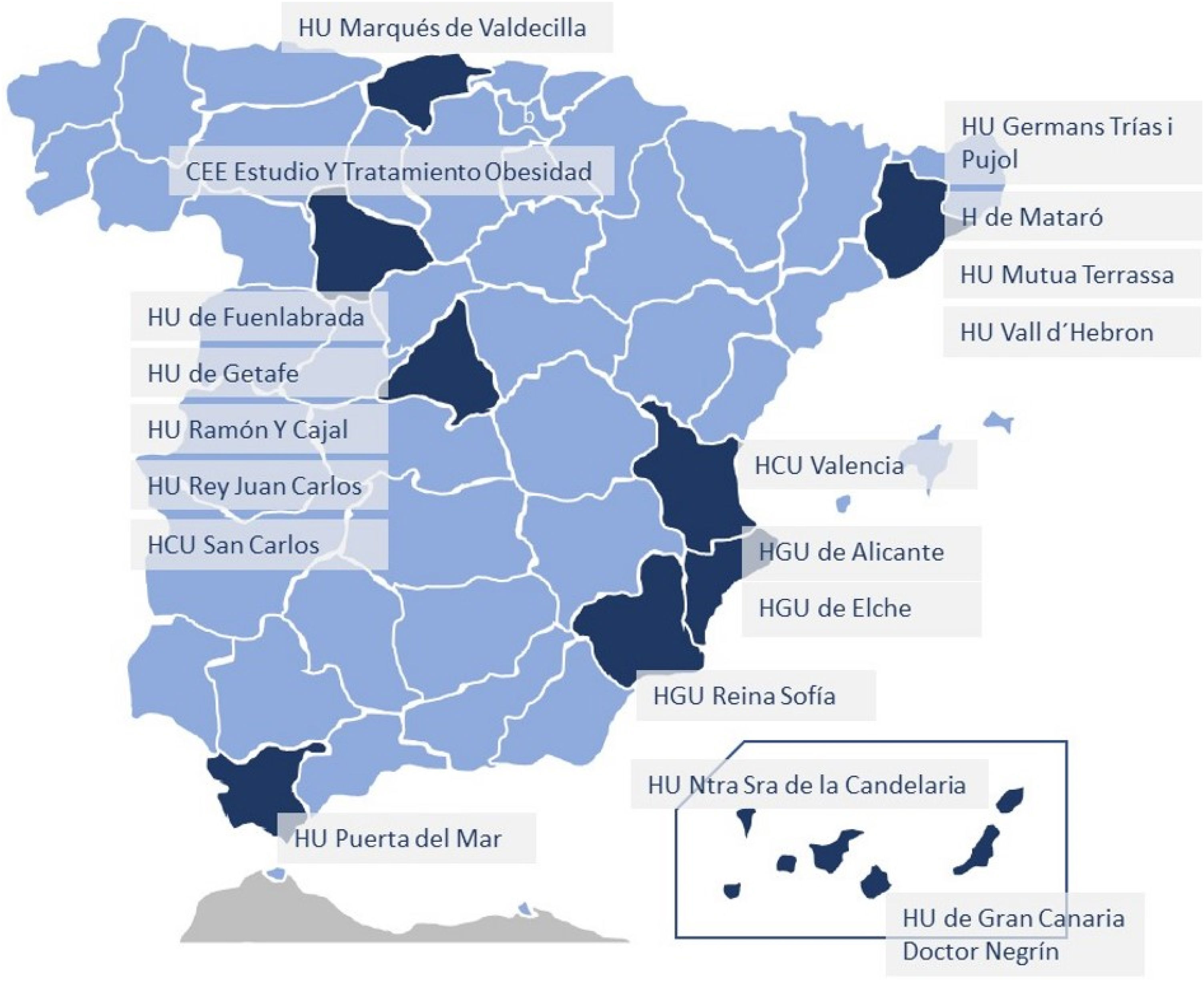

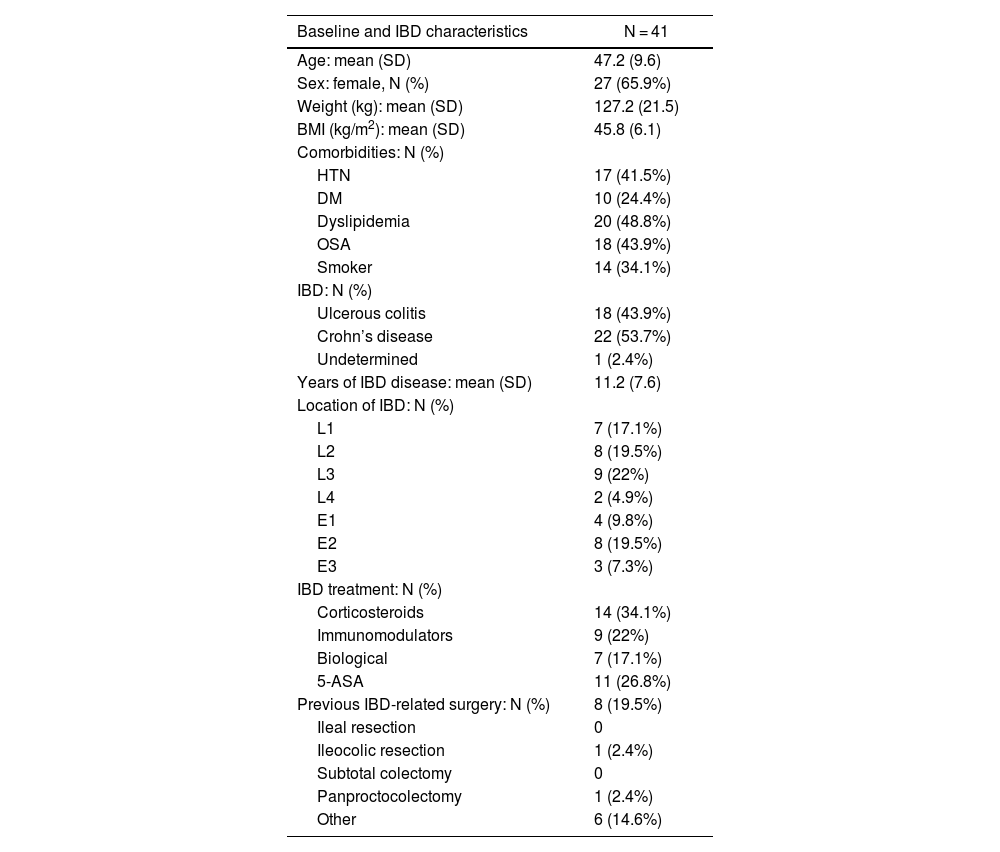

ResultsA total of 18 hospitals from all over Spain have participated in the registry (Fig. 1), including a total of 41 patients: 18 (43.9%) previously diagnosed with UC, 22 (53.7%) with CD, and one indeterminate colitis (2.4%). Mean age was 47.2 ± 9.6 years, and 65.9% of the sample were women. The mean preoperative BMI was 45.8 ± 6.1 kg/m2, and the comorbidities presented are shown in Table 1 (dyslipidemia and OSAS were the most frequent). In our study population, 34.1% were smokers. Among the patients included, the mean time to diagnosis of IBD was 11.2 ± 7.6 years. Regarding the location of the disease, the most frequent within CD was L3 (ileocolic), while in UC it was E2 (left colitis). Preoperatively, 9 patients (22%) were being treated with immunomodulators, 7 (17.1%) with biologic treatments, and 11 (26.8%) with 5-ASA, while 34.1% had been treated with corticosteroids. Among the surgeries performed previously secondary to IBD, 2 patients with CD had required ileocolic resection and panproctocolectomy, respectively.

Baseline characteristics of patients with IBD treated with bariatric surgery.

| Baseline and IBD characteristics | N = 41 |

|---|---|

| Age: mean (SD) | 47.2 (9.6) |

| Sex: female, N (%) | 27 (65.9%) |

| Weight (kg): mean (SD) | 127.2 (21.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2): mean (SD) | 45.8 (6.1) |

| Comorbidities: N (%) | |

| HTN | 17 (41.5%) |

| DM | 10 (24.4%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 20 (48.8%) |

| OSA | 18 (43.9%) |

| Smoker | 14 (34.1%) |

| IBD: N (%) | |

| Ulcerous colitis | 18 (43.9%) |

| Crohn’s disease | 22 (53.7%) |

| Undetermined | 1 (2.4%) |

| Years of IBD disease: mean (SD) | 11.2 (7.6) |

| Location of IBD: N (%) | |

| L1 | 7 (17.1%) |

| L2 | 8 (19.5%) |

| L3 | 9 (22%) |

| L4 | 2 (4.9%) |

| E1 | 4 (9.8%) |

| E2 | 8 (19.5%) |

| E3 | 3 (7.3%) |

| IBD treatment: N (%) | |

| Corticosteroids | 14 (34.1%) |

| Immunomodulators | 9 (22%) |

| Biological | 7 (17.1%) |

| 5-ASA | 11 (26.8%) |

| Previous IBD-related surgery: N (%) | 8 (19.5%) |

| Ileal resection | 0 |

| Ileocolic resection | 1 (2.4%) |

| Subtotal colectomy | 0 |

| Panproctocolectomy | 1 (2.4%) |

| Other | 6 (14.6%) |

BMI = body mass index; HTN = hypertension; DM = diabetes mellitus; IBD = inflammatory bowel disease; Location: L1 (ileal); L2 (colon); L3 (ileocolic); L4 (ileal + gastrointestinal); E1 (proctitis); E2 (left colitis); E3 (extensive). Results are expressed as means (+/- standard deviation) or absolute value (percentage).

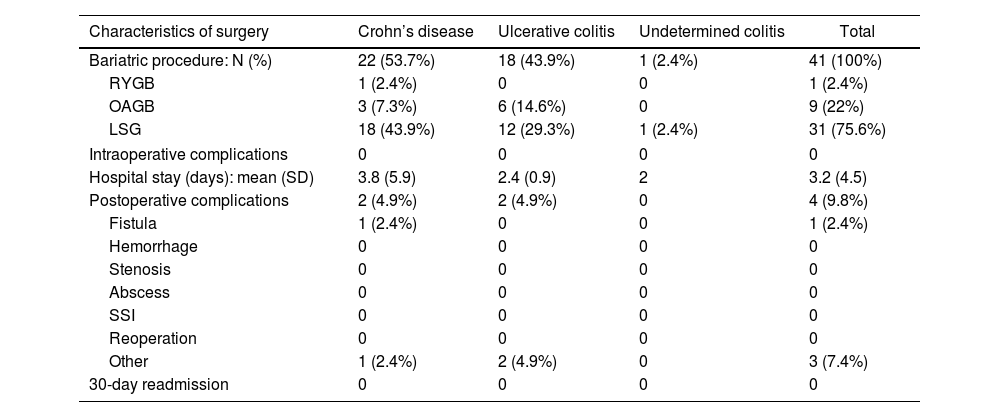

The bariatric procedures performed included: 31 (75.6%) laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomies (LSG), one (2.4%) Roux-en-Y gastrojejunal bypass (RYGB), and 9 (22%) one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) (Table 2). In patients diagnosed with CD, 81.8% of the interventions performed were LSG, while in those diagnosed with UC, 66.6% underwent surgery using this restrictive technique.

Characteristics of surgery according to type of IBD (CD vs UC).

| Characteristics of surgery | Crohn’s disease | Ulcerative colitis | Undetermined colitis | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bariatric procedure: N (%) | 22 (53.7%) | 18 (43.9%) | 1 (2.4%) | 41 (100%) |

| RYGB | 1 (2.4%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.4%) |

| OAGB | 3 (7.3%) | 6 (14.6%) | 0 | 9 (22%) |

| LSG | 18 (43.9%) | 12 (29.3%) | 1 (2.4%) | 31 (75.6%) |

| Intraoperative complications | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hospital stay (days): mean (SD) | 3.8 (5.9) | 2.4 (0.9) | 2 | 3.2 (4.5) |

| Postoperative complications | 2 (4.9%) | 2 (4.9%) | 0 | 4 (9.8%) |

| Fistula | 1 (2.4%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.4%) |

| Hemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stenosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Abscess | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SSI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Reoperation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 1 (2.4%) | 2 (4.9%) | 0 | 3 (7.4%) |

| 30-day readmission | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

RYGB = Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; OAGB = one-anastomosis gastric bypass; LSG = laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy; SSI = surgical site infection. The results are expressed as means (+/− standard deviation) or absolute value (percentage).

During the surgical procedures, no intraoperative complications were recorded. The mean hospital stay of the operated patients was 3.2 ± 4.5 days (longer in patients with CD than in patients with UC, although not statistically significant). During the postoperative period, overall complications were recorded in 9.8%. Among them, it is worth noting one proximal third fistula after LSG (early complication), which was resolved by conservative treatment. Another patient underwent initial LSG, which was later converted to RYGB 8 years after the intervention due to significant uncontrolled reflux associated with pulmonary microabscesses. Minor complications included a urinary tract infection and opening of a trocar wound. There were no postoperative readmissions. One patient diagnosed with extensive UC (with very poor control due to not keeping coloproctology appointments), who was treated with LSG, presented massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding a few months later (unrelated to bariatric surgery), which ended in death.

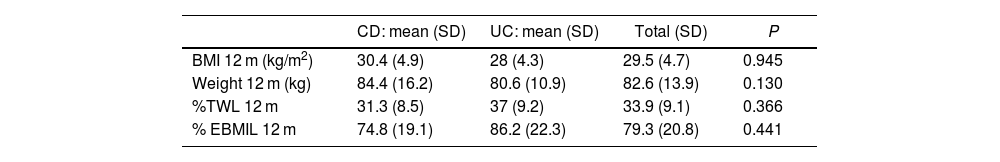

Regarding weight loss 12 months after surgery, mean BMI was 29.5 ± 4.7 kg/m2, presenting a %TWL of 33.9% ± 9.1% (31.3% ± 8.5% in CD vs 37% ± 9.2% in UC; P = .366) (Table 3). The weight loss results were higher in patients treated with mixed techniques than those treated with LSG, although these differences were not statistically significant (%TWL: 41.7% ± 6.4% vs 31.4% ± 8.5%; P = .603).

Weight evolution after bariatric surgery and its comparison between CD and UC.

| CD: mean (SD) | UC: mean (SD) | Total (SD) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI 12 m (kg/m2) | 30.4 (4.9) | 28 (4.3) | 29.5 (4.7) | 0.945 |

| Weight 12 m (kg) | 84.4 (16.2) | 80.6 (10.9) | 82.6 (13.9) | 0.130 |

| %TWL 12 m | 31.3 (8.5) | 37 (9.2) | 33.9 (9.1) | 0.366 |

| % EBMIL 12 m | 74.8 (19.1) | 86.2 (22.3) | 79.3 (20.8) | 0.441 |

BMI = body mass index; %TWL= % total weight lost; %EBMIL = excess BMI lost. The results are expressed as means (+/− standard deviation).

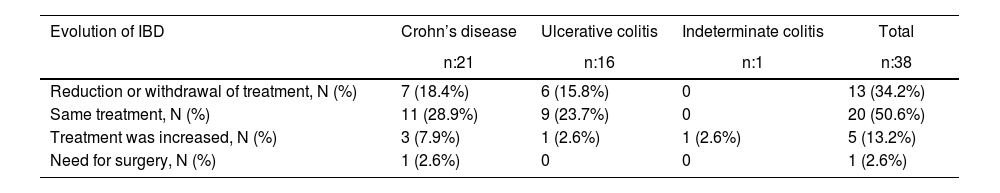

As for the evolution of the disease (IBD) and the need for treatment, practically half of the sample maintained the same treatment, while 13.2% required increased treatment and 34.2% reduced treatment. Only one patient required surgery (perianal abscess drainage) secondary to a CD flare-up (Table 4).

Evolution of IBD after bariatric surgery.

| Evolution of IBD | Crohn’s disease | Ulcerative colitis | Indeterminate colitis | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n:21 | n:16 | n:1 | n:38 | |

| Reduction or withdrawal of treatment, N (%) | 7 (18.4%) | 6 (15.8%) | 0 | 13 (34.2%) |

| Same treatment, N (%) | 11 (28.9%) | 9 (23.7%) | 0 | 20 (50.6%) |

| Treatment was increased, N (%) | 3 (7.9%) | 1 (2.6%) | 1 (2.6%) | 5 (13.2%) |

| Need for surgery, N (%) | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.6%) |

The results are expressed as absolute value (percentage).

In recent years, obesity has been increasing worldwide, while more and more cases of IBD are also being diagnosed and treated. As a result, and contrary to what is conventionally expected, we are more frequently faced with patients diagnosed with IBD who present with severe obesity and may be candidates for bariatric surgery.7,8

In our study, we have analyzed a sample from a national registry of patients with IBD who have undergone bariatric surgery. The results obtained indicate that they are effective procedures with low surgical risk, which may help in the decision-making process when treating this type of patient, who we will undoubtedly see more frequently in our consultations. As far as we know, this is the third largest registry published with a one-year follow-up, evaluating complications as well as the evolution of IBD.15,17

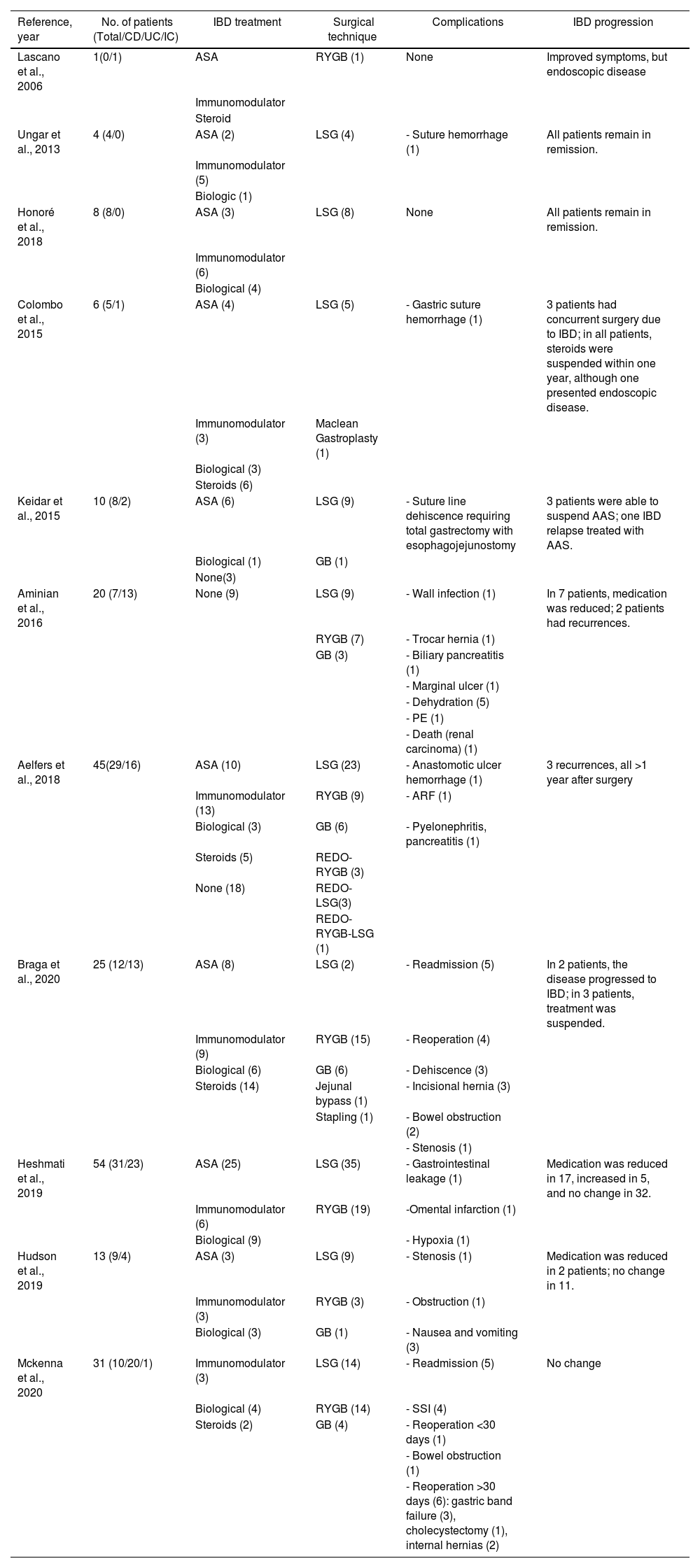

While analyzing the results, we have observed a tendency to perform restrictive techniques in patients diagnosed with CD (81.8%). Meanwhile, mixed or malabsorptive interventions are somewhat more prevalent in patients with UC (33.4%), although without ever exceeding the preference of the restrictive technique. Obviously, the reason is the potential risk in patients diagnosed with CD, as there may be some intestinal involvement that increases complications after RYGB-type techniques (fistulae, stricture, etc). An additional risk is that these patients may require some type of intestinal resection in the long term, which may increase the previously created malabsorption. Therefore, like most studies, a restrictive technique is preferred (this trend has been more evident in patients diagnosed with CD). Thus, Heshmati et al., in their series of 54 patients published in 2019, performed LSG in 35 (64.8%) and RYGB in 19 (35.2%) patients.17 Aminian et al., in their series of 20 patients, performed restrictive techniques in 60% (9 LSG and 3 gastric band) and RYGB in 40%.16 In one of the largest series published to date (45 patients), Aelfers et al. described a percentage of restrictive techniques of 64%.15 In the review of the literature shown in Table 5,14–18,21–26 we have observed how, in 9 out of the 11 studies reviewed, restrictive techniques exceeded mixed or malabsorptive methods. Interestingly, our registry is the first to show the OAGB technique for this type of patient. This is possibly due to the considerable number of hospitals in our country where this intervention is performed. Furthermore, it is not only used in patients diagnosed with UC (14.6%), but also in those with CD (7.3%). This option could be considered as it is a technique with a single anastomosis, which would obviate the need for a second anastomosis (intestinal connection). In any case, and since these are the first cases published, these data should be taken with caution given the need for future studies evaluating their results (specifically for patients with IBD).

Review of the literature of patients with IBD treated with bariatric surgery.

| Reference, year | No. of patients (Total/CD/UC/IC) | IBD treatment | Surgical technique | Complications | IBD progression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lascano et al., 2006 | 1(0/1) | ASA | RYGB (1) | None | Improved symptoms, but endoscopic disease |

| Immunomodulator | |||||

| Steroid | |||||

| Ungar et al., 2013 | 4 (4/0) | ASA (2) | LSG (4) | - Suture hemorrhage (1) | All patients remain in remission. |

| Immunomodulator (5) | |||||

| Biologic (1) | |||||

| Honoré et al., 2018 | 8 (8/0) | ASA (3) | LSG (8) | None | All patients remain in remission. |

| Immunomodulator (6) | |||||

| Biological (4) | |||||

| Colombo et al., 2015 | 6 (5/1) | ASA (4) | LSG (5) | - Gastric suture hemorrhage (1) | 3 patients had concurrent surgery due to IBD; in all patients, steroids were suspended within one year, although one presented endoscopic disease. |

| Immunomodulator (3) | Maclean Gastroplasty (1) | ||||

| Biological (3) | |||||

| Steroids (6) | |||||

| Keidar et al., 2015 | 10 (8/2) | ASA (6) | LSG (9) | - Suture line dehiscence requiring total gastrectomy with esophagojejunostomy | 3 patients were able to suspend AAS; one IBD relapse treated with AAS. |

| Biological (1) | GB (1) | ||||

| None(3) | |||||

| Aminian et al., 2016 | 20 (7/13) | None (9) | LSG (9) | - Wall infection (1) | In 7 patients, medication was reduced; 2 patients had recurrences. |

| RYGB (7) | - Trocar hernia (1) | ||||

| GB (3) | - Biliary pancreatitis (1) | ||||

| - Marginal ulcer (1) | |||||

| - Dehydration (5) | |||||

| - PE (1) | |||||

| - Death (renal carcinoma) (1) | |||||

| Aelfers et al., 2018 | 45(29/16) | ASA (10) | LSG (23) | - Anastomotic ulcer hemorrhage (1) | 3 recurrences, all >1 year after surgery |

| Immunomodulator (13) | RYGB (9) | - ARF (1) | |||

| Biological (3) | GB (6) | - Pyelonephritis, pancreatitis (1) | |||

| Steroids (5) | REDO-RYGB (3) | ||||

| None (18) | REDO-LSG(3) | ||||

| REDO-RYGB-LSG (1) | |||||

| Braga et al., 2020 | 25 (12/13) | ASA (8) | LSG (2) | - Readmission (5) | In 2 patients, the disease progressed to IBD; in 3 patients, treatment was suspended. |

| Immunomodulator (9) | RYGB (15) | - Reoperation (4) | |||

| Biological (6) | GB (6) | - Dehiscence (3) | |||

| Steroids (14) | Jejunal bypass (1) | - Incisional hernia (3) | |||

| Stapling (1) | - Bowel obstruction (2) | ||||

| - Stenosis (1) | |||||

| Heshmati et al., 2019 | 54 (31/23) | ASA (25) | LSG (35) | - Gastrointestinal leakage (1) | Medication was reduced in 17, increased in 5, and no change in 32. |

| Immunomodulator (6) | RYGB (19) | -Omental infarction (1) | |||

| Biological (9) | - Hypoxia (1) | ||||

| Hudson et al., 2019 | 13 (9/4) | ASA (3) | LSG (9) | - Stenosis (1) | Medication was reduced in 2 patients; no change in 11. |

| Immunomodulator (3) | RYGB (3) | - Obstruction (1) | |||

| Biological (3) | GB (1) | - Nausea and vomiting (3) | |||

| Mckenna et al., 2020 | 31 (10/20/1) | Immunomodulator (3) | LSG (14) | - Readmission (5) | No change |

| Biological (4) | RYGB (14) | - SSI (4) | |||

| Steroids (2) | GB (4) | - Reoperation <30 days (1) | |||

| - Bowel obstruction (1) | |||||

| - Reoperation >30 days (6): gastric band failure (3), cholecystectomy (1), internal hernias (2) |

CD = Crohn’s disease; UC = ulcerative colitis; IC = indeterminate colitis; RYGB = Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; OAGB = one-anastomosis gastric bypass; LSG = laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy; GB = adjustable gastric band; ARF: acute renal failure; PE = pulmonary embolism; SSI = surgical site infection.

Based on the data obtained, bariatric surgery in patients with IBD could be considered safe and effective. The 12-month weight loss results show %TWL and %EBMIL results that would be in line with what is expected after bariatric surgery in an obese population without IBD.27–30 The patients who were treated with OAGB or RYGB presented more weight loss compared to those treated with LSG, although these differences were not statistically significant (%TWL: 41.7% ± 6.4 % vs 31.4% ± 8.5%; P = .603). However, the beneficial effects of bariatric surgery are not explained solely by the restriction and malabsorption induced by the surgery itself. Changes in the microbiome could play a role in this mechanism. This is how Luijten et al. describe it in a recent systematic review, where they observed how the microbiome was affected by surgery and profound changes occurred in the first year of follow-up, which were associated with weight loss.31

As for overall complications (9.8%), these are within the quality standards established in bariatric surgery.27 Only one patient treated with LSG presented postoperative fistula, which did not require surgical intervention. This is a typical complication after this surgical technique,32 so it could hardly be attributed to the presence of IBD. If we compare our results with those published in the literature,19,25,33 we see that they are within the range considered normal (and even lower than in other series). The systematic review and meta-analysis published by Garget et al. shows that the combined rate of early and late adverse events was 15.9% (95%CI, 9.3%–25.9%) and 16.9% (95%CI, 12.1%–23.1%), respectively. Patients undergoing RYGB experienced almost double the overall adverse events compared to LSG, although the differences were not statistically significant.19 The reason for this difference is unknown, although one explanation could be that some UC patients had a previous extensive total colectomy, which could make subsequent bariatric surgical procedures technically challenging.

Regarding the evolution of IBD, our results show that, one year after BS, previous IBD treatment is reduced or withdrawn in a considerable percentage of patients (34%). These results are similar to other studies. Aminian et al.16 found that 9 out of 10 IBD patients who received pharmacotherapy to control their active IBD experienced significant improvement in their IBD-related symptoms during follow-up.

The systematic review and meta-analysis by Garg et al.19 showed that bariatric surgery had no effect on IBD medication in practically half of patients (like our study), while 45% received less and 11% required an increase in medication. CD seemed more sensitive to bariatric intervention, while most patients with UC did not experience changes in their mediation. This could be explained by the fact that many patients underwent total colectomy or had an inactive form of the disease before bariatric surgery.

Braga Neto et al.25 found that, after bariatric surgery, there were fewer IBD complications (specifically less use of rescue corticosteroids and IBD-related surgeries) compared to non-operated control IBD patients. These benefits appear to be due to a decrease in the proinflammatory effect (TNF-α) associated with obesity (specifically reductions in high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, TNF factor, and interleukin-6) and, consequently, less need for rescue therapy with corticosteroids.25,34 According to recent studies, another potential beneficial mechanism in these patients may be mediated by changes in the microbiome and its role in response to anti-integrins and mediating the efficacy of thiopurines.35–38 These results support the theory that bariatric surgery can not only be safe and effective, but that it could positively influence the course of the disease.19

As should be done in all patients undergoing bariatric surgery, strict nutritional control is recommended for patients who have also been previously diagnosed with IBD, both after surgery and in the medium-long term.

The limitations of this study are related to its retrospective nature based on a national registry, entailing a risk of possible losses, together with the fact that it is a small patient sample with a follow-up of only one year. Thus, it is difficult to draw conclusions. In addition, and despite repeated communications from scientific societies, not all hospitals that manage patients with these characteristics have participated in this study. As for the treatment of IBD, no data have been obtained regarding the time of its suspension or introduction, which undoubtedly would have helped obtain new conclusions. Despite these limitations, this is one of the largest cohorts presented in the literature, which may support the results presented by other authors.

Conclusions: First of all, this registry will allow us to determine the interventions conducted to date according to IBD type, as well as complications and evolution of weight. It may also be continually expanded over time to include new collaborating hospitals, which will increase the number of patients as well as the variables to be analyzed. Bariatric surgery in patients previously diagnosed with IBD can be considered effective for weight loss and safe, as it is associated with a low percentage of complications (which initially do not exceed the obese population treated with bariatric surgery not diagnosed with IBD). LSG is the most commonly performed bariatric procedure in patients diagnosed with IBD, showing no differences in terms of the number of complications compared to other mixed techniques (RYGB, OAGB). Bariatric surgery appears to improve the evolution of IBD in a significant percentage of the population. Studies with larger series and longer follow-up periods are needed, which will allow us to reach more consistent results. Undoubtedly, the national registry tool will contribute to achieving these objectives.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Grupo ReNacEIBar: Acosta-Mérida Mª Asunción. Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria; Balibrea del Castillo José M. Hospital Universitario Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona (Barcelona); Carbajo Caballero Miguel Ángel. Centro de excelencia para el estudio de la obesidad y la diabetes (Valladolid); Ferrer-Ayza Manuel. Obesidad Almería (Almería); Gianchandani Moorjani Rajesh Haresh. Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria (Santa Cruz de Tenerife); Gómez Carmona Zahira. Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas (Almería);González Valverde Francisco Miguel. Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía (Murcia); López Useros Antonio. Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla (Santander);Mans Muntwyler Esther. Hospital de Mataró; Martín Antona Esteban. Hospital Clínico Universitario San Carlos (Madrid); Martín García-Almenta Ester. Hospital Clínico Universitario San Carlos (Madrid). Mayo Osorio Mª de los Ángeles. Hospital Regional Universitario Puerta Del Mar (Cádiz);Martí Gelonch Laura. Hospital Universitario Donostia (San Sebastián); Ocaña Jiménez Juan. Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal (Madrid); Ortiz Sebastián Sergio. Hospital General Universitario Dr. Balmis, ISABIAL(Alicante); Pérez Romero Noelia. Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona); Pérez Santiago Leticia. Hospital Clínico Universitario (Valencia);Puértolas Rico Noelia. Hospital Universitario Mutua Terrassa (Barcelona); Recarte Rico María. Hospital Universitario la Paz (Madrid);Reina-Duarte Ángel. Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas (Almería); Rubio-Gil Francisco. Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas (Almería); Sánchez-Guillén Luis. Hospital General Universitario de Elche; Sánchez Pernaute Andrés. Hospital Clínico Universitario San Carlos (Madrid). Talavera Eguizábal Pablo.Hospital Clínico Universitario San Carlos (Madrid); Valero Sabater Mónica. Hospital Royo Villanova (Zaragoza); Vidaña Márquez Elisabet. Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas (Almería); Vives Espelta Margarida.Hospital Universitario Sant Joan de Reus (Tarragona).