Laryngotracheal or subglottic stenosis (SGS) is a rare condition characterized by a narrowing of the internal diameter of the cricoid and/or upper part of the trachea. The most common cause is inflammation, often due to prolonged intubation or previous tracheostomy, although other causes include Wegener’s granulomatosis, sarcoidosis, infections, esophageal reflux, or external laryngeal trauma. Nevertheless, a significant number of SGS cases remain idiopathic.1

To address airway obstruction pathology, endoscopic treatment options are considered, including balloon dilatation, laser therapy, stent placement, or mechanical dilation with rigid bronchoscopy.2 However, despite short-term success, recurrences are frequent. Surgical intervention remains the treatment of choice for operable patients with tracheal or laryngotracheal stenosis.3 Cricotracheal resection and reconstruction represent highly complex procedures with significant morbidity and mortality rates.3–5

Due to the rarity of this condition, reported cases are scare and from various hospitals.6 Nonetheless, expertise is consolidated at referral centers with established programs and through coordination among various units involved in treatment. Collaboration among thoracic surgery, otolaryngology, pulmonology, and anesthesia departments is essential to optimize pre- and postoperative care. A specialized group is required for detailed case study and decision-making to establish the most suitable therapeutic plan for each patient.4 Furthermore, postoperative nursing care and experience in managing potential complications are essential.

At our medical center, the arrival of a team member with extensive experience in laryngotracheal pathology led to the creation of new units, collaboration with other departments (such as Pulmonology and Otolaryngology), and the initiation of nursing training. Additionally, pre- and post-operative collaboration with physiotherapy and speech therapy units was established.

The objective of this study is to describe our experience with SGS and surgery of the proximal third of the trachea performed at our hospital from June 2017 to December 2023, after having established the specialized programs, units, and collaborations mentioned above. Simple stenoses (defined by a membrane of less than 1 cm in length) and cases with inoperable criteria were excluded.

We reviewed patient medical records, CT images, surgical reports, techniques performed, outcomes, and complications. Follow-up bronchoscopies were performed one, 3, and 6 months after surgery for clinically satisfactory cases, followed by annual spirometry.

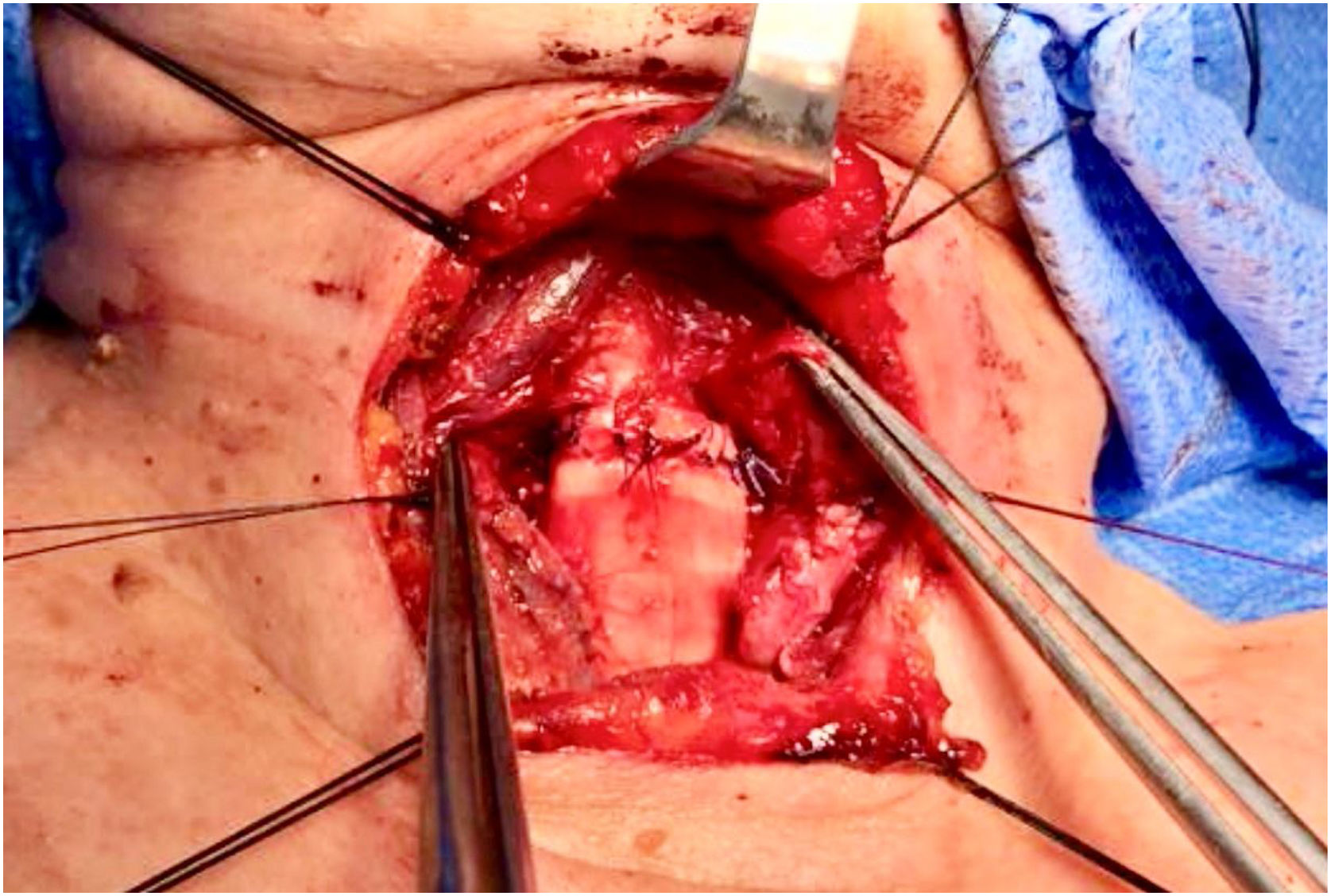

During the study period, 18 patients (7 males and 11 females) with a median age of 59 years (range 34–80 years) underwent surgery. Idiopathic etiology was identified in half of the cases. Surgical techniques included tracheal resection and end-to-end anastomosis (Fig. 1) in 7 cases (38.9%), whereas partial anterior cricoid section with pathological mucosa, flap coverage of the membranous part, and thyroid cartilage-trachea anastomosis were performed in 10 cases (55.6%). Laryngofissure was necessary in one case, with temporary placement of a Montgomery T-tube.

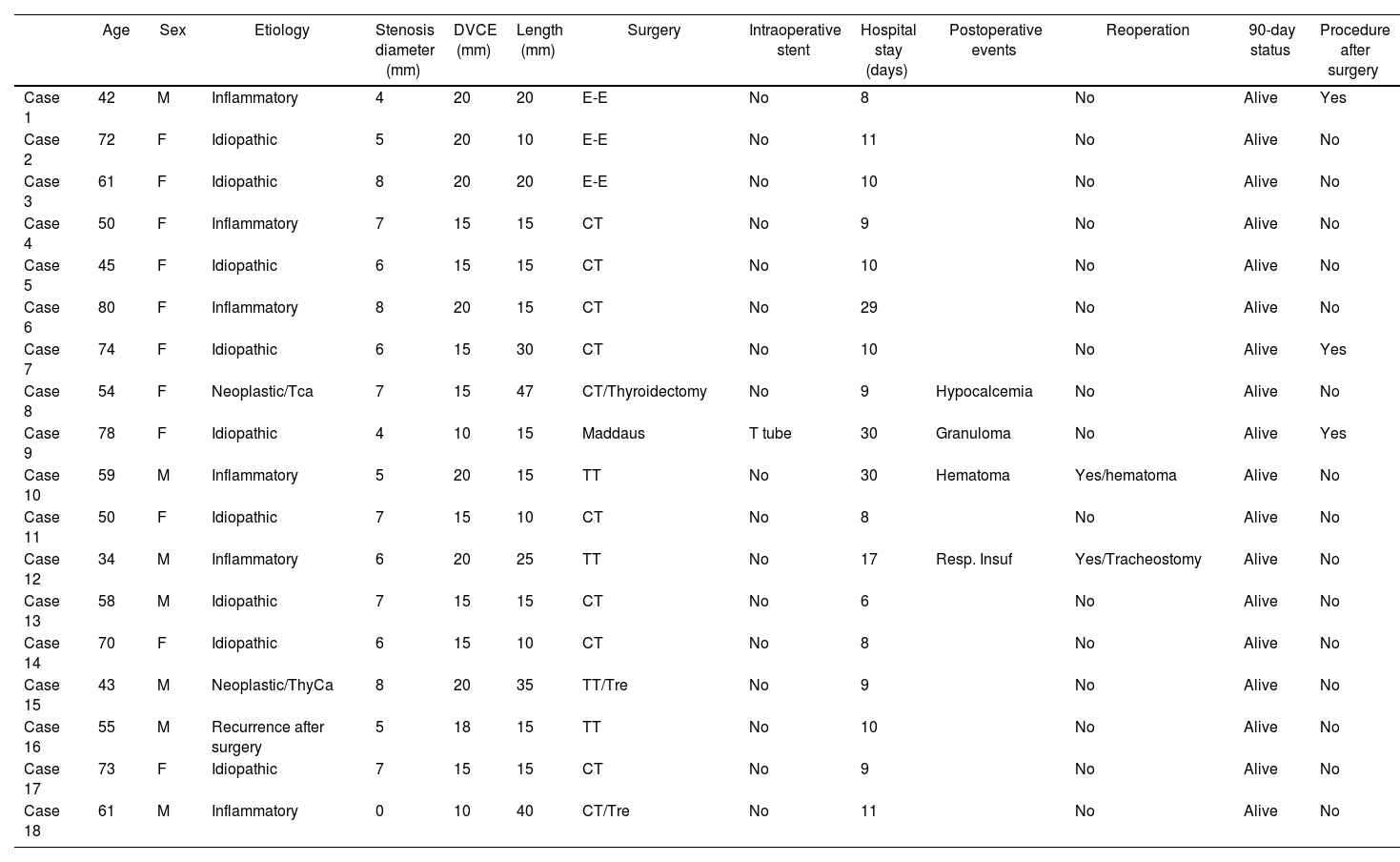

Immediate improvement in dyspnea was observed in all patients. Four cases (22.2%) experienced postoperative complications: granulomas at the suture line, hypocalcemia secondary to total thyroidectomy performed concurrently, hematoma requiring reoperation, and exacerbation with subsequent desaturation requiring temporary orotracheal intubation and distal tracheostomy in a patient with congenital heart disease.3,7,8 Decannulation was successful within a few days. In 3 instances, a diagnostic endoscopic procedure was conducted due to suspected complications, and one case requiring dilation of the suture area. In all patients, follow-up was satisfactory, with no additional complications (Table 1).

Characteristics of the operated patients.

| Age | Sex | Etiology | Stenosis diameter (mm) | DVCE (mm) | Length (mm) | Surgery | Intraoperative stent | Hospital stay (days) | Postoperative events | Reoperation | 90-day status | Procedure after surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 42 | M | Inflammatory | 4 | 20 | 20 | E-E | No | 8 | No | Alive | Yes | |

| Case 2 | 72 | F | Idiopathic | 5 | 20 | 10 | E-E | No | 11 | No | Alive | No | |

| Case 3 | 61 | F | Idiopathic | 8 | 20 | 20 | E-E | No | 10 | No | Alive | No | |

| Case 4 | 50 | F | Inflammatory | 7 | 15 | 15 | CT | No | 9 | No | Alive | No | |

| Case 5 | 45 | F | Idiopathic | 6 | 15 | 15 | CT | No | 10 | No | Alive | No | |

| Case 6 | 80 | F | Inflammatory | 8 | 20 | 15 | CT | No | 29 | No | Alive | No | |

| Case 7 | 74 | F | Idiopathic | 6 | 15 | 30 | CT | No | 10 | No | Alive | Yes | |

| Case 8 | 54 | F | Neoplastic/Tca | 7 | 15 | 47 | CT/Thyroidectomy | No | 9 | Hypocalcemia | No | Alive | No |

| Case 9 | 78 | F | Idiopathic | 4 | 10 | 15 | Maddaus | T tube | 30 | Granuloma | No | Alive | Yes |

| Case 10 | 59 | M | Inflammatory | 5 | 20 | 15 | TT | No | 30 | Hematoma | Yes/hematoma | Alive | No |

| Case 11 | 50 | F | Idiopathic | 7 | 15 | 10 | CT | No | 8 | No | Alive | No | |

| Case 12 | 34 | M | Inflammatory | 6 | 20 | 25 | TT | No | 17 | Resp. Insuf | Yes/Tracheostomy | Alive | No |

| Case 13 | 58 | M | Idiopathic | 7 | 15 | 15 | CT | No | 6 | No | Alive | No | |

| Case 14 | 70 | F | Idiopathic | 6 | 15 | 10 | CT | No | 8 | No | Alive | No | |

| Case 15 | 43 | M | Neoplastic/ThyCa | 8 | 20 | 35 | TT/Tre | No | 9 | No | Alive | No | |

| Case 16 | 55 | M | Recurrence after surgery | 5 | 18 | 15 | TT | No | 10 | No | Alive | No | |

| Case 17 | 73 | F | Idiopathic | 7 | 15 | 15 | CT | No | 9 | No | Alive | No | |

| Case 18 | 61 | M | Inflammatory | 0 | 10 | 40 | CT/Tre | No | 11 | No | Alive | No |

F: Female; M: Male; TCa: Tracheal carcinoma; ThyCa: Thyroid carcinoma; E-E: end-to-end resection; CT: Cricotracheal resection: TRe: Tracheal release; Resp Insuf: Respiratory insufficiency.

Our series results align with literature reports regarding complications. Overall morbidity and mortality rates after tracheal resection have been reported to range from 17% to 45% and from 0% to 2.4%, respectively.9 The most important risk factors9 include diabetes, resection length, reoperation, laryngotracheal surgery, and previous tracheostomy.5,10

Given the surgical complexity of cricotracheal resections, high postoperative complication rates and limited incidence, centralized treatment would benefit both patients and surgeons. Collaboration on a national scale and centralization of cases are imperative. Klug et al. reported significant variations in laryngotracheal surgery and postoperative care among 15 medical centers in 5 Nordic countries, highlighting the need for standardized protocols.6

In conclusion, surgical intervention is the treatment of choice for SGS. We present our initial experience with a specialized tracheal surgery program. Through dedicated programs, multidisciplinary work and specialization, satisfactory results were achieved, with immediate improvement in patient symptoms and an acceptable morbidity rate.

FundingThis study received no funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.