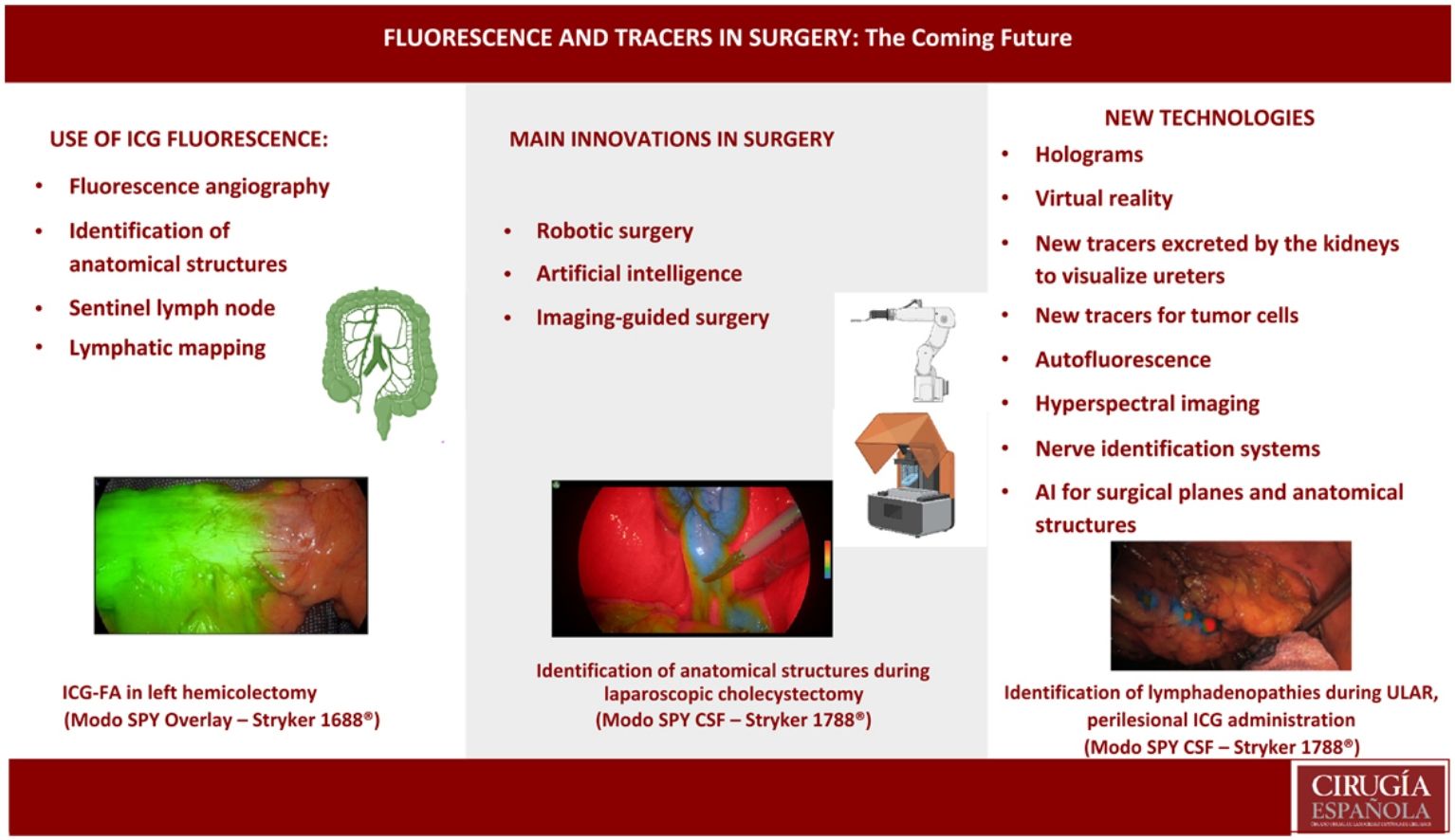

The revolution that we are seeing in the world of surgery will determine the way we understand surgical approaches in coming years. Since the implementation of minimally invasive surgery, innovations have constantly been developed to allow the laparoscopic approach to go further and be applied to more and more procedures. In recent years, we have been in the middle of another revolutionary era, with robotic surgery, the application of artificial intelligence and image-guided surgery. The latter includes 3D reconstructions for surgical planning, virtual reality, holograms or tracer-guided surgery, where ICG-guided fluorescence has provided a different perspective on surgery.

ICG has been used to identify anatomical structures, assess tissue perfusion, and identify tumors or tumor lymphatic drainage. But the most important thing is that this technology has come hand in hand with the potential to develop other types of tracers that will facilitate the identification of tumor cells and ureters, as well as different light beams to identify anatomical structures. These will lead to other types of systems to assess tissue perfusion without the use of tracers, such as hyperspectral imaging. Combined with the upcoming introduction of ICG quantification, these developments represent a real revolution in the surgical world. With the imminent implementation of these technological advances, a review of their clinical application in general surgery is timely, and this review serves that aim.

Las revoluciones de las que estamos siendo testigos en el mundo de la cirugía, van a determinar la forma de entender el abordaje quirúrgico en los próximos años. Desde la implantación de la cirugía mínimamente invasiva constantemente se han desarrollado innovaciones que facilitan que el abordaje laparoscópico llegue más lejos y se aplique cada vez a más procedimientos. En los últimos años estamos inmersos en otra época de revoluciones tales como la cirugía robótica, la aplicación de inteligencia artificial y la cirugía guiada por imagen. Esta última incluye las reconstrucciones 3D para la planificación quirúrgica, la realidad virtual, los hologramas o la cirugía guiada por trazadores, donde la florescencia guiada por ICG ha supuesto una forma distinta de enfocar la cirugía.

El ICG se ha utilizado para identificar estructuras anatómicas, para valorar perfusión de tejidos, para identificar tumores o el drenaje linfático de los mismos. Pero lo más importante, es que esta tecnología ha venido de la mano de un potencial desarrollo de otro tipo de trazadores, que facilitarán la identificación de células tumorales, uréteres, de diferentes haces de luz para identificar estructuras anatómicas, derivando a otro tipo de sistemas para valorar la oxigenación de los tejidos sin uso de trazadores, como las imágenes hiperesprectales. Todo esto aunado a la llegada de la cuantificación del ICG representa una revolución real en el mundo quirúrgico. Con la inminente implementación de este desarrollo tecnológico, es oportuna una revisión de su aplicación clínica en cirugía general y esta revisión tiene ese objetivo.

We are currently witnessing a very special time in the world of surgery — a revolution that will determine the way we understand surgical approaches in coming years. If the term revolution is defined as a decisive change in the way we conceive something, then there have been 3 major revolutions in surgery since its beginnings: anesthesia, which allows us to carry out the procedures we do today; transplantation, that magical action of transferring an organ to another person to allow them to live; and the advent of minimally invasive surgery. Since the implementation of the latter, innovations have been constantly emerging that have made it easier for the laparoscopic approach to go further and be applied to increasingly more procedures.

In recent years, we have again been immersed in another era of revolution, which has been fundamentally led by 3 great concepts: robotics, which have made it easier to reach any place of the human body, even at impossible angles, yet in an ergonomic manner, which opens the future to automation of different surgical phases; artificial intelligence and big data, whose application aids in decision making and facilitates learning; and lastly, imaging-guided surgery, whose aim is to see beyond and see the invisible in order to obtain better results.

Imaging guidance entails different concepts, including 3D reconstruction for surgical planning, virtual reality, holograms, or tracer-guided surgery, where indocyanine green-guided florescence has provided a different way of understanding surgery, with the growing number of applications, results offered, and opportunities it provides in different fields.

Indocyanine green (ICG) has been used to identify different anatomical structures, assess tissue perfusion, identify lymphatic drainage of different tumors, and even to identify tumors themselves. But most importantly, this technology has come hand in hand with the potential development of other tracers, which will facilitate the identification of tumor cells and ureters, using different beams of light to identify anatomical structures, while also leading to other types of systems to assess tissue oxygenation without the use of tracers, such as hyperspectral images. Without a doubt, the scope of possibilities that accompany the expansion of the concept, and the imminent improvements in its use (such as quantification), will represent a turning point in our current notion of the operating room and surgical procedures, which is a real revolution in the world of surgery.

FluorescenceIndocyanine green (ICG) is a fluorescent staining agent that, under near-infrared (NIR) vision, is commonly used as a contrast medium for medical diagnosis.1 It was developed during World War II for color-imaging purposes for use in photography. In 1956, its clinical use in humans was approved for the first time, and in 1957 its use in human medicine was tested.2 In 1959, it became the first NIR dye approved by the FDA (US Food and Drug Administration) for clinical applications, such as angiography, lymphatic and biliary imaging, and for image-guided oncological surgery.2

ICG is a water-soluble anionic tricarbocyanine dye containing a seven-carbon p-conjugated chain. Its chemical structure consists of polycyclic elements connected by a long carbon chain. While the polycyclic elements are responsible for the lipophilic properties of ICG, the sulfate groups confer hydrophilicity.3 After intravenous administration, ICG rapidly binds to plasma proteins and is eliminated unchanged by the bile, with no enterohepatic recirculation, with a plasma half-life of 3−5 min and hepatic metabolism.4 When injected directly into tissue, ICG binds to proteins and reaches the nearest lymph node within a few minutes, subsequently binding to regional lymph nodes 1−2 h after injection.5

In recent years, the use of ICG fluorescence has spread in surgical settings, especially minimally invasive approaches in general surgery, thanks to the technology used in laparoscopic and robotic approaches.

Current uses of icg fluorescenceTissue perfusion using indocyanine green fluorescence angiography (ICG-FA)The assessment of tissue vascularization to determine viability, especially prior to performing anastomosis, has been demonstrated in different areas of general surgery, such as colorectal, esophageal, gastric, bariatric, hernia and abdominal wall reconstruction surgery.6

The most obvious advantage of the ICG-FA technique is the real-time visualization of blood perfusion to tissues and blood flow related to arterial vascularization. However, it does not evaluate the speed of venous return or tissue washout. Once the vessels and tissues are dyed, the marked enhancement lasts about 5 min until the liver secretes the ICG intact into the bile.4

Colorectal surgeryAs previously demonstrated by different studies, adequate blood supply is one of the most important factors to prevent anastomotic leakage (AL).5–11 Along these lines, a series of articles have been published in which it is evident that ICG-FA is a very useful tool to help reduce the leak rate in colorectal surgery.5–11

A prospective study evaluated the usefulness of ICG-FA during robot-assisted sphincter-preserving surgery in patients with rectal cancer. The study included 436 patients distributed into 2 groups.9 A group of 123 patients was administered intravenously 10 mg before and after the anastomosis, and in the other group of 313 patients, 63 did not undergo ICG-FA. The results showed that the dehiscence rate was significantly lower in the ICG group compared to the non-ICG group (0.8% vs. 5.4%, respectively9). Another study analyzed the use of ICG-FA according to type of colorectal surgery (site of the division line either colon or rectum) and concluded that the use of ICG entails significantly greater changes in the initially proposed division line in the left hemicolectomy followed by anterior resection.14 Therefore, although ICG-FA is very useful, it may have even greater value in this type of intervention, probably due to the variable vascular anatomy and the dependence of vascularization on the preservation and state of the vascular arcades.

Based on these results, we can conclude that ICG-FA is an effective method to help reduce anastomotic leaks after colorectal surgery5–14 (Fig. 1).

Esophageal surgeryThe use of the stomach for reconstruction after esophagectomy is a widely practiced technique. Anastomotic leak rates, which range between 6.2% and 27%, are one of the main problems that correlate with the postoperative morbidity, mortality and prognosis of these patients.15–18

One area that has deficient vascularization during these anastomoses is located in the upper part of the plasty. In order to ensure adequate vascularization to the anastomosis of the gastric pull-up to the esophagus, the use of ICG-FA has been suggested, administering ICG intravenously at 3 different moments: before performing the gastric plasty, after performing it, and before placing it in the thorax. Lastly, there are groups that use ICG-FA once the esophageal repair has been placed in the thorax and prior to the anastomosis.18–20

ICG fluorescence is a promising method for reducing the risk of AL after esophagectomy. Ladak et al. published a meta-analysis describing a reduction in AL of 69% when some type of intervention or change to the initially planned surgery was performed and ICG was used.20

Gastric surgeryIn the case of a gastrectomy, vascularization is an important factor in the development of AL.21,22 In a prospective study that included 20 patients undergoing surgery for early-stage gastric cancer with either robotic (14 patients) or laparoscopic (6 patients) gastrectomy and preservation of the pylorus,21 ICG was administered at the beginning of surgery to identify the vascular anatomy before performing the planned procedure. The conclusion of this study was that real-time vascularization assessment with ICG fluorescence during minimally invasive gastrectomy was found to be feasible with minimal added complexity.21 Preliminary results indicate that intraoperative vascular imaging using ICG-FA is useful even to identify the anatomy and origin of small vessels.20,21

Bariatric surgeryIn bariatric surgery, when performing sleeve gastrectomy, one of the most feared complications is a gastric leak along the line of division, which seems to be closely related to ischemic problems in the stomach. Similar to other techniques, the risk of inadequate vascular supply to an anastomosis could lead to AL.22–24 A recently published systematic review attempted to assess the importance of the use of ICG-FA compared to AL tests and traditional tissue perfusion assessment, concluding that the percentage of patients in whom a change in approach occurred intraoperatively due to ICG was 3.8%, which reduced the risk of postoperative complications. ICG fluorescent imaging in bariatric surgery is a promising tool.24

Abdominal wall reconstructionFluorescence with ICG also seems to be useful in reducing complication rates in cases of hernia and abdominal wall reconstruction.25–29 Several studies have reported the usefulness of ICG-FA to assess the vascularization and bilateral blood supply to skin flaps and subcutaneous tissue in order to assess whether it helped make decisions during the intervention, concluding that ICG was helpful for both decision making as well as to reduce wound-related complications by avoiding hypoperfused tissues or necrosis.25–29

ICG dosage for ICG-FAVariability is observed among the authors regarding the ICG dose and type of administration. Morales-Conde et al. published a guide, in which their conclusions and recommendations are to use a standard dose for ICG-FA of 15 mg, with an increased intravenous dose of 25 mg for bariatric surgery.29

Use of ICG for the identification of anatomical structuresBile ductFluorescence with ICG allows virtual cholangiography to be performed in real time during dissection in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, thereby identifying anatomical variations and avoiding situations of potential risk of bile duct injury.

When ICG concentrates at the liver and is excreted through the bile, it makes it possible to outline the anatomy of the biliary tree and the junction between the cystic and the common hepatic ducts.31

One of the associated problems is that the high fluorescence of the liver can prevent or hinder the identification of the biliary tree and, especially if the injection has been very recent, prevents correct visualization of the bile duct.30 To avoid these issues, some authors have proposed earlier preoperative injection or direct gallbladder injection,31–33 although it is a somewhat cumbersome technique and not always possible. For the reasons previously mentioned and for perfect definition of the bile duct with less hepatic contrast, ICG should be administered 3−8 h before surgery,29–34 although new vision systems enable injection even during anesthesia induction (Fig. 2).

ParathyroidIatrogenic injuries to the parathyroid glands are the most common complication after total thyroidectomy. Fluorescence with ICG can be useful for the identification of the parathyroid glands during thyroid surgery, as well as to ensure vascularization after thyroidectomy.35–38 Recently, a very interesting alternative has been developed, which consists of auto-fluorescence (AF) of the parathyroid glands without the need to administer ICG. Reports show AF to be 96 %–98 % effective in identifying the parathyroid glands.39,40 If ICG is used, most authors recommend a dose of 5 mg intravenously, usually after mobilizing the thyroid. However, when AF is combined with the administration of ICG, the results to date have proven to be quite reliable due to the sensitivity achieved, which ranges from 84 % to 100 %.39,40

Identification of uretersIatrogenic injury to the ureters during colorectal or pelvic surgery is a complication that is associated with increased hospital stay, costs associated with the process, and short- and long-term morbidity and mortality.41 The incidence of ureteral injury during pelvic surgery is around 2% (range 1 %–10 %), and 80% of cases are detected after the procedure.41–43 Identification and visualization of the ureter is recommended during pelvic surgery in order to avoid such injury. However, adhesions, obesity or an incorrect dissection plane can contribute to incorrect or non-identification of ureters.44,45 For this reason, catheterization of the ureters is used in selected procedures where a high risk of ureteral injury is anticipated. However, the usefulness that the placement of a ureteral stent can have in open surgery (where its path can be identified by palpation) is not equally applicable for the identification of the ureter during a minimally invasive procedure, given the absence of adequate tactile sensation with laparoscopic and robotic instruments.46,47 For this reason, illuminated ureteral catheters have been introduced, which, although they help to visually locate the path of the ureter, have the same adverse effects as common catheters. The results published about the placement of ureteral catheters do not show a reduction in iatrogenic ureteral injuries during the intervention, in addition to prolonging the surgical time due to the difficulty entailed in certain cases.42,43 Furthermore, it should be noted that the placement of a ureteral stent is not a harmless action, since complications may arise, such as urinary tract infection due to manipulation, hematuria, kidney injuries, temporary ureteral obstruction and, occasionally, urethral injuries. Most of these complications are temporary and reversible, but they increase the morbidity and healthcare costs of the process.45,47

In this context, one possible application of ICG is the identification of ureters using this fluorophore. To do so, a cystoscopy is performed prior to surgery to identify the desired urinary meatus, which is catheterized for retrograde injection of diluted ICG. The binding of this substance to the proteins of the ureteral epithelium allows the path of the ureter to be subsequently identified using a fluorescence imaging system. The dilution used varies according to the different authors.43,45,47,48 Several studies demonstrate that the instillation of ureteral ICG is safe and provides a very high localization rate during pelvic interventions.42,43,45–48 In the series of 16 cases by White et al., the ureteral localization success rate was 94% (15/1647; Rodríguez-Zentner et al. achieved identification of the ureter in the 30 laparoscopic cases performed, with no ureteral injuries;43 meanwhile, Soriano showed an identification rate of the right ureter in 97% and the left in 100% of the 83 robotic procedures registered.48

There are different methods described for the injection of the fluorescent substance, from simple injection once the ureter has been catheterized 1 cm, or up to 20 cm, or groups who leave the catheter in place. The mean instillation time by cystoscopy is short: 11.5 min (range 4–21) for White47 and 22.4 min for Rodríguez-Zentner.43 The series by Soriano et al., which compares the simple instillation of ICG with the placement of a stent, shows a shorter time in patients in whom a stent is not inserted of 4 min (range 3−8) vs. 13.5 min, (range 10–21.5 min); P < .001.48 Simple instillation of ICG into the ureter without complete catheterization is sufficient for its identification and avoids some of the complications that this procedure entails, as Soriano demonstrates, with a lower rate of acute kidney injury and hematuria.48

Looking to the future, if a molecule with physical characteristics similar to ICG could be used to be detected in real-time imaging and whose elimination was via the kidney, this innovation would be more easily usable since it would be a faster procedure and would avoid manipulation of the urinary tract. In this context, new intravenous fluorescent dyes with renal clearance, such as fluorescein sodium49 and IRDye® 800-BK,50 have been used in experimental models to test the penetration of fluorescence into the ureters, with promising results for surgical practice. In addition, the liposomal formulation of ICG enables its excretion in urine in animal models and may represent a development in this sense, with the currently most popular fluorophore.51

Therefore, immunofluorescence used for intraoperative ureteral identification is safe and effective, showing good results with fewer side effects than standard catheterization. The new technologies under development with intravenous fluorescents would provide similar results, avoiding urological manipulation for their use.

Identification of tumorsLiver tumorsHepatic elimination of ICG provides identification of liver lesions by fluorescence.52 Healthy liver tissue eliminates ICG within 2 h, while tumor tissue may retain it due to the compression that occurs in the bile ducts.53,54 Furthermore, hepatocytes located in the transition zone between the tumor and healthy tissue are not capable of excreting the dye to the bile ducts, which is why the fluorescence in liver metastases is observed as a ring around the lesion, while the fluorescence area of a hepatocellular carcinoma is identified within the lesion.55 ICG can help better delimit resection margins, since studies in which ICG has been used to plan liver resection have reported that resection margins were clearly visualized in 89%–100% of surgeries.54,55

There are 2 routes of administration described, intravenous and intraportal, and the former is more frequently used.

Pancreatic tumorsThe application of fluorescence with ICG has been used to identify pancreatic tumors and, although it is not currently used routinely, its use in the not-too-distant future seems promising. Specifically, it has been used to verify the complete removal of the mesopancreas in laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomies, and, as total removal of the retroperitoneal margin is an important prognostic factor in this type of tumors, its value could be quite significant.56 The pancreatic tissue of the uncinate process is difficult to differentiate from the surrounding fatty tissue, which encompasses the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and its nerve plexus.57–59 Using intraoperative injection of intravenous ICG, the initial fluorescence of the SMA disappears while it gradually accumulates in the pancreas, resulting in a clear contrast effect between the uncinate process and the SMA, thereby outlining said retroperitoneal margin.58,59

Adrenal tumorsThe identification of the adrenal glands (AG), as well as the identification of their anatomical outline, can be made difficult by the surrounding retroperitoneal fat.60–64 Based on the difference in perfusion between the AG and the surrounding tissues, these glands, and the different types of tumors located in them, can be identified.60–64 Adrenocortical tumors are easily recognized by their greater fluorescence; medulla tumors (pheochromocytomas), however, are hypofluorescent.

Peritoneal metastasesPreoperative detection of peritoneal metastases is often difficult with the imaging techniques available to us.64–66 Adequate diagnosis and staging are important to select the best therapeutic option.65,66 The clinical application of fluorescence with ICG in peritoneal carcinomatosis should be reserved for patients with a carcinomatosis index of less than 8, since the value of fluorescence is limited in patients with a preoperative diagnosis of extensive peritoneal metastatic dissemination.66 The use of ICG could have a promising future with an important role in this type of interventions, as it could assist in intraoperative decision making.

Use of ICG for sentinel lymph node identification and lymphatic mappingColorectal surgery - lymphatic mappingThe use of ICG in intraoperative lymph node detection in colorectal cancer can be used both to detect the sentinel node and to perform lymphatic mapping during lymphadenectomy.67–74 Several studies have concluded that fluorescence with ICG provides valuable information to detect tumor-draining lymph nodes in colorectal surgery. This characteristic is especially important if these nodes are not present in the usual dissection area, and this information would therefore change the surgical strategy.68,69 Moreover, intraoperative lymphatic mapping can also help define lymphatic dissemination pathways in patients who need to undergo a second intervention and who have previously had lymphatic tissue resected.68

It has also been observed that ICG could be less reliable in patients with rectal cancer undergoing surgery after neoadjuvant therapy.68 However, its use could be of value in mapping the lateral pelvic wall in low and middle rectal cancer, guiding extended lymphadenectomy in patients in whom it is indicated. It could also help reduce the morbidity of lateral pelvic dissection.70

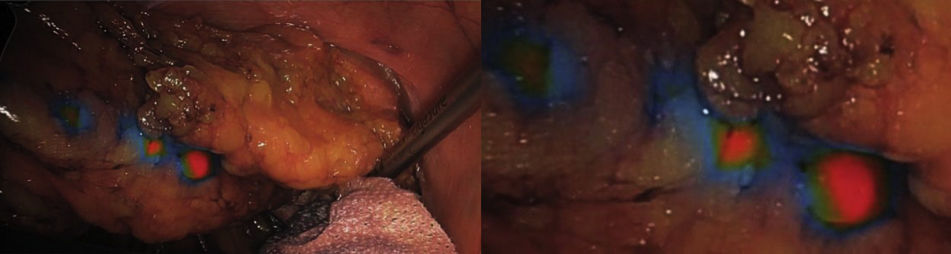

Peritumoral injection of ICG can be performed in various ways. Several groups have described administering it by colonoscopy prior to the start of the intervention, the most common technique being injection into the 4 cardinal points around the tumor.67–72 It has also been administered in the same way in neoplasms of the mid-lower rectum by rectoscopy prior to surgery to identify lateral pelvic lymphadenopathies, which can be performed more comfortably with rectoscopy at the beginning of the intervention.70–72 In a different approach, ICG can be administered with a peritumoral subserous injection at the beginning of the laparoscopic intervention, with adequate identification of lymphatic drainage to the sentinel lymph node and also providing visualization of the lymphatic mapping corresponding to the tumor drainage area.73,74 It seems that there are no differences in the type of administration.67–74 Regarding the dose, expert groups recommend a standard dose of 2 wheals at a concentration of 3 cm3 with 15 mg of ICG. In the colon, it would be administered in the submucosa at the beginning of the intervention; for the medium-high rectum, it would be administered in the submucosa 12–24 h earlier. In the case of the lower rectum, administration would be at the beginning of surgery with an anoscope29 (Fig. 3).

Esophageal surgery - lymphatic mappingEsophageal cancer spreads in a multidirectional manner through the submucosal lymphatics to the regional lymph node stations. Lymphatic metastases are one of the most important prognostic factors, which is why extensive lymphadenectomy is necessary to improve the prognosis.75–78 Fluorescence with ICG in lymphadenectomy of esophageal cancer is described in several clinical studies. The administration of ICG is carried out in the esophageal submucosa in the 4 quadrants of the tumor, either endoscopically or transmurally, and lymphadenopathies become visible 15−30 min after the injection.75–78 It has been hypothesized that albumin could be preferable to distilled water to dilute the ICG, since it increases the retention time of the dye in the draining lymph nodes, the time necessary for esophagectomy and lymphadenectomy, thus preventing lymphadenopathies from not being identified in their entirety.76 Hachey et al. indicated the superiority of this albumin dilution procedure in the case of esophageal cancer due to the poor retention of ICG in the lymph nodes with distilled water.76 Yuasa et al. demonstrated the detection with this system of 95% of the affected lymph nodes, which is very useful to avoid extensive lymphadenectomies that entail high morbidity.77 Regarding the dose, 1.25 mg/mL is administered in the submucosa in the 4 quadrants, and 0.5cm3 peritumoral by endoscopy 12−24 h before the procedure.29

Stomach surgery - sentinel lymph node and lymphatic mappingStudies published about the identification of sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) by fluorescence with ICG in these tumors have reported identification rates between 90% and 100%, although this rate drops to 0 in the case of T4 tumors.79 Bok et al. demonstrated the usefulness of ICG to detect SLN laparoscopically in T1N0M0 tumors, where standard treatment had been endoscopic submucosal resection. This has led to new and broad opportunities for the clinical use of fluorescence in the identification of the sentinel lymph node in early stages, ensuring that no patient with positive lymphadenopathies goes unidentified.79 This study describes the change in approach based on the results of intraoperative SLN study, converting from submucosal resection to gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy, which occurred in one of the 13 patients included in the study, in whom tumor cells were detected in one of the resected SLN.79

With regards to lymphatic mapping, most studies only talk about fluorescence-guided lymphatic mapping with ICG in a descriptive manner, since in reality the initially planned surgical strategy is not modified.81–90 In terms of the route of administration and when to perform it, several ways have been described. Some groups administer it by endoscopy in 4 cardinal peritumoral points at a submucosal level one day before the procedure, while other groups choose to do it by endoscopy, also with submucosal injection at the beginning of the intervention.81–90 Laparoscopic administration has also been described in the peritumoral subserosa at the beginning of the intervention.81–88

In one of the few studies carried out in our setting, Senent et al. describe a series of 142 patients with gastric adenocarcinoma who underwent laparoscopic gastrectomy at a Spanish hospital between January 2017 and December 2022. In total, 42 patients received preoperative injection of indocyanine green to guide lymphadenectomy. Their results were compared with a retrospective cohort of 42 patients,90 demonstrating the advantages of using this technology. The feasibility of lymphatic mapping with indocyanine green was 95.5%. No complications associated with indocyanine green injection were observed. The indocyanine green group had a significantly higher number of lymph nodes recovered than the non-indocyanine green group (32.67 vs. 25.14; P = .013). In 47.6% of patients in the indocyanine green group, lymphadenectomy was extended outside the standard D2 dissection area based on indocyanine green uptake.90

All studies conclude that ICG fluorescence imaging easily allows for high sensitivity and real-time guided imaging for sentinel node identification and lymphatic mapping in gastric cancer.81–90 As for the dose, it is similar to the esophagus: 1.25 mg/mL in the submucosa in the 4 quadrants, 0.5cm3 peri-tumor by endoscopy 12−24 h before surgery.29

Breast surgery - sentinel lymph nodeICG fluorescence has demonstrated high sensitivity for detecting the SLN in breast cancer when ICG is used, which would avoid the use of radioisotopes.91–94 One study has assessed the detection of the SLN by administering 1.6 mL of ICG bound to albumin (ICG:HSA [human serum albumin]). This combination favors ICG to rapidly bind to the lymphatic drainage and SLN when injected intravenously, and premixing ICG:HSA improves kinetics and increases brightness threefold.92

Another study carried out in 202 patients in stage IIA who underwent breast-conserving surgery made a comparison between a group in which the SLN was identified with ICG and another group using a combination of ICG plus indigo carmine dye.94 The combination between the dye and ICG resulted in a significantly higher SLN detection rate (96.4% vs. 83.7%). Therefore, both studies conclude that combined therapy including ICG could be a feasible and safe method for identifying SLN.93–94

Melanoma surgery - lymphatic mappingICG fluorescence may also be useful for lymphatic mapping in patients with melanoma.95 The dose of ICG usually used in melanoma is 2 mL, at a concentration of 0.25 mg/mL. With preoperative administration of 2 mL of ICG (2.5 mg/mL), an 80% lymph node detection rate has been achieved with ICG.95

Advances and needs of the use of fluorescence with ICGThe assessment of ICG-FA with near-infrared (NIR) vision has demonstrated its usefulness in the prevention of anastomotic leaks. However, the surgeon’s subjective visual interpretation of the perfusion signal may limit the validity and standardization of the technique.

ICG quantificationSurgical procedures in which part of the mesentery is resected may benefit from ICG-FA with NIR vision. However, quantification of NIR fluorescence images is essential for standardization of tissue vascularization assessment.96–99

In routine clinical practice, ICG is evaluated using a visual analogue scale, depending on the appearance of the tissue and the intensity of the green projected. This evaluation is very useful, but it is subjective, not allowing for an objective or independent measurement of the degree of vascularization, which could lead to variability in the technique and make it difficult to standardize.

In this context, most studies focus on observing and analyzing different regions of interest (ROI) to assess the intensity of ICG according to its administration time.96–100

Faber et al. published a study in which they recorded videos with standard fluorescence images. Subsequently, fluorescence videos were quantified by drawing contiguous ROI in the intestine. For each ROI, a time-intensity curve was drawn, from which perfusion parameters were analyzed. In addition, the interobserver agreement of the surgeon’s subjective perception of fluorescence was evaluated. The study included 20 patients undergoing colorectal surgery. From the time-intensity curves, 3 different ICG-FA perfusion patterns were identified. Interobserver agreement was poor-moderate.96 This study demonstrated that ICG-FA quantification is a feasible method to differentiate between different perfusion patterns. Furthermore, the poor-moderate agreement of the subjective interobserver reading of ICG-FA clearly shows the need for objective quantification using integrated systems.96

Recently, Nijssen et al. have published a study that sought to measure the agreement in the assessment of ICG-FA between 2 quantification software programs developed independently. This retrospective analysis included standard ICG-FA recordings from patients who had undergone esophagectomy with gastric conduit reconstruction between August 2020 and February 2022. The recordings were analyzed using 2 quantification software packages: AMS and CPH. The study included 70 ICG-FA recordings prior to anastomosis.97 The Bland-Altman analysis indicated a mean relative difference of +58.2% in measurement when comparing AMS software to CPH. Neither measurement had a significant relationship with the AL rate.97 This is the first study that has demonstrated technical differences in computer applications that may lead to discrepancies in ICG-FA quantification in clinical cases. Possible variations between quantification methods performed by different software should be taken into account when interpreting studies reporting quantitative ICG-FA parameters and the parameters obtained, as there may be limited external validity.97

In the systematic review by Pollman et al., a search that included ICG quantification among other criteria identified 61 studies for inclusion. The main categories of ICG quantification were esophageal surgery (24.6%), reconstructive surgery (24.6%) and colorectal surgery (21.3%). The main variable of interest was AL (41%), followed by evaluation of flap perfusion (23%) and the identification of structures and organs (14.8%). The analysis was conducted mainly with “manufacturer” software (44.3%) and “free use” software (15.6%). The most frequently analyzed parameter was ICG-FA intensity over time, followed by intensity alone or the intensity/background ratio for identification of structures and organs. Intraoperative ICG quantification could gain greater importance with the increasing impact of robotic surgery and machine learning algorithms for image and video analysis.100

Therefore, it is essential to develop and improve the area of ICG-FA quantification of the integrated systems that are beginning to be used in the NIR systems included in the optical and video equipment used for minimally invasive surgery. With the intention of standardizing the criteria for measurement, this would facilitate their routine use and make them more reproducible.

Clinical criteria for the use of ICGThere are several criteria that should be taken into account when using ICG fluorescence systematically, such as the moment when the arrival of the dye to the tissues provides greater clinical value, what factors could alter or delay the arrival of the ICG, or at what distance from the tissues should the optical system be placed during a surgical intervention.

In an experimental study, M. Diana et al. concluded that, with the FLER system, the most important moment when delimiting a line of ischemia or a possible line of division for anastomosis is the initial arrival of the ICG.101 Serra-Aracil et al. published a prospective observational study in patients undergoing elective laparoscopic colorectal surgery. The optimal time for ICG analysis was verified in a sample of 20 patients, and the optimal distance in 10 patients. ICG was administered intravenously, and colonic vascularization was quantified using SERGREEN. The authors observed that the fluorescence intensity reaches its peak after about 1.5 min. and that the saturation of the ICG is inversely proportional to the distance between the chamber and the tissue. They conclude that the optimal time to determine ICG in the colon is between 1.5 and 3.5 min (both in the right and left colon), and the optimal distance is 5 cm. This information will facilitate establishing comparison parameters in normal and pathological situations.102

It is important to keep in mind that there are several factors, such as inflammatory processes and obesity, that may cause the ICG to not be adequately visualized when trying to identify anatomical structures or for mapping of lymphatic vessels. For example, it may be more difficult to identify the biliary structures in an obese patient with cholecystitis.5,30,103 Caution should also be used when the ICG dose is repeated within a short period of time because the ICG could accumulate, and dissimilar photodynamic behavior has been observed in these situations.100,103

Autofluorescence and future uses of fluorescence without tracersIdentification of structures based on light waves without tracersAutofluorescence is a unique case among the fluorescence techniques. When talking about this phenomenon, reference is made to the intrinsic capacity that some natural compounds in biological tissues have, which consists of the emission of light in the spectrum of wavelengths between 500 and 700 nm under the influence of lights with shorter wavelengths. Numerous studies explain how molecules are found in biological tissues that, when a tissue is healthy, have standard concentration patterns.104 Therefore, knowing what these concentrations are and knowing how these substances respond under the presence of a light that excites them, we can detect changes in their concentration. Below is a list of some examples, according to the tissue in which they are found:

- •

Skin: The decrease in fluorescence in melanomas results from the increase in collagen and tissue hyperpigmentation under 335 nm excitation light. This can be very useful and effective in the early detection of melanocytic alterations.105

- •

Bronchi: Thanks to the combination of autofluorescence emitted in the red and green range of the electromagnetic spectrum, it provides high sensitivity in the detection of intraepithelial neoplastic lesions.106

- •

Digestive tract surgery: Autofluorescence in colon surgery under a combination of images taken with excitation lights of 330, 370 and 430 nm provides sensitive differentiation of adenomatous and hyperplastic polyps from normal colon tissue.107

- •

Similarly, we can find usefulness in neoplastic breast,108 brain,109 and mouth and larynx tissue, where it has been observed that both cavities and the oral mucosa respond to blue light.110

- •

The use of fundus autofluorescence in the diagnosis of retinal detachments and glaucoma has increased considerably in recent years.111

- •

Another of the most innovative uses is the precise localization of nerves during surgery.

Nerve identification is of great importance in both surgery and regional anesthesia. Optical-based techniques can identify the tissue through differences in optical properties, such as spectral wave absorption and dispersion.

In the Langhout et al. study, the authors evaluated the potential of optical spectroscopy (diffuse reflectance spectroscopy) for in vivo clinical nerve identification. Eighteen patients undergoing inguinal lymph node resection or removal of a soft tissue tumor in the groin were included to measure the femoral or sciatic nerve and surrounding tissues. In vivo optical measurements were performed using diffuse reflection spectroscopy (400−1600 nm) on the nerve, adipose tissue near the nerve, muscle, and subcutaneous fat. The water and fat content parameters showed significant differences (P < .005) between the nerve and all surrounding tissues.112

Iatrogenic nerve injuries contribute significantly to postoperative morbidity and occur more frequently than we would like. Currently, there are no clinically adopted means to visualize nerves intraoperatively beyond the surgeon’s visual assessment. Therefore, recent efforts have focused on visualizing the nerves within the surgical field to help prevent nerve damage altogether. Last year, Graham et al. proposed the use of diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) for intraoperative nerve detection and visualization.105 Initially, the optimal wavelengths for nerve discrimination were identified by preparing the rat sciatic nerve in vivo. Subsequently, the image-based DRS was validated for the visualization of nerves through hyperspectral images, then the contrast sources were determined at identified wavelengths, and wavelength selection was verified in human subjects using probe-based diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Finally, ratiometric spectral imaging was validated to improve intraoperative nerve visualization.113

In general, this is a field where expansion is anticipated. An example of this is its application in endocrine surgery for the location of the recurrent laryngeal nerve after thyroidectomy. According to a very recent paper by Dip et al., a prospective study that included 65 patients undergoing thyroidectomy, the application in this procedure is 100% sensitive and specific.114 Thirty randomly selected pairs of white light and fluorescent images were reviewed independently by 2 examiners to compare the RLN detection rate, number of branches, and the length and minimum width of the nerves visualized. The authors concluded that, in 65 patients and 81 nerves, RLN detection was improved markedly and consistently with autofluorescence neuroimaging during thyroidectomy, with a sensitivity and specificity of 100%.114

New tracersNew tracers for the identification of tumor cellsSome studies have shown that ICG-like fluorescent tracers can be labeled with artificially created antibodies of cell-surface tumor markers.115–117 The most advanced fluorescent agents for tumor targeting fall into 2 categories: antibodies or ligands for proteins and receptors on cancer cell surfaces and substrates for cancer-specific metabolic pathways.116 Almost all are labeled with ICG or one of the red cyanine dyes.116 ICG-based compounds are very attractive because they can be detected with many of the fluorescent detection devices currently available in operating rooms.116 With minor modifications, this equipment can also detect cyanines and other dyes with near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF).116

Promising antibodies have been developed against carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) for colorectal, breast, lung, and gastric cancer, prostate-specific antigen for prostate cancer, and antigen 125 for ovarian cancer.115,116 For instance, XenoLight CF750, an anti-CEA antibody conjugated with ICG and NIR probe, was able to detect peritoneal tumor deposits in the 4 gastric cancer cell lines, including micrometastases <2 mm in mouse models.117

Fluorescence is more sensitive than normal light visualization and identification in an intraoperative setting.117 Fluorescence studies report the contrast ratio between tumor signal and normal tissue signal to quantify results.118 Fluorescent labeling of tumors can help visibility of the tumor margin, achieve R0 resection and identify metastatic lesions, with the ultimate goal of achieving a lower recurrence rate.119,120 Furthermore, the possibility of detecting metastatic disease is essential to plan the most appropriate surgical treatment.121 In this line, articles have been published about the use of tracers with ICG or carbon nanoparticles (CN) to detect metastatic invasion of lymph nodes in the case of colorectal or gastric tumors.122–125 It can also be applied for lymphatic mapping in several types of cancer that present aberrant drainage pathways, which could lead to local recurrence when not resected.122–125 Diagnostic laparoscopy is often used to detect metastatic disease, which may initially go undetected and lead to unnecessary resection of the primary tumor, so cancer diagnosis and treatment could be greatly improved if the extent of the disease is adequately detected with the help of this technology.117

The use of these tracers is still not widespread in clinical practice, however, it is necessary to continue this line of research so that future studies are able to improve the R0 resection rate and reduce the rates of recurrence and metastasis.

Alternatives to fluorescence – hyperspectral imagingRecently, hyperspectral imaging (HI) has been developed for its use in surgery as an alternative to fluorescence.126 This optical imaging modality allows information from across the electromagnetic spectrum to be measured.126 For medical applications, the most interesting and investigated spectral range encompasses wavelengths between the visible and near-infrared range (450–1000 nm).126

HI has great potential in both diagnostic and therapeutic areas.126 Therefore, this innovative spectral imaging technology may find potential applications in pathology, histology, and clinical diagnosis.126 Furthermore, it is a promising optical tool for image-guided surgery.127 Recently, different lines of research have used hyperspectral microscopic technology to identify differences in color and texture, classify pathological tissue without labels and implement the diagnosis of carcinoma with “deep learning” techniques.128,129

In fact, it is known that the way a biological structure or tissue interacts with light can reveal the real-time state of anatomical structures, such as disease progression or the effect of a localized systemic therapy.126 HI relies on autofluorescence of tissue chromophores to quantify and perform the relative absorption of endogenous organic compounds, such as oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin and antibodies, over a wide range of wavelengths, providing intraoperative evaluation with a large field of vision.130 When interacting with light, a biological structure undergoes various phenomena, such as absorption and scattering.126 Absorption is due to the natural presence of chromophores in the tissue, such as hemoglobin and water, while dispersion is caused by a non-homogeneous structure.131 Therefore, light reflected and transmitted from the medium carries quantitative diagnostic information about the state and content of the medium.126 HI is a non-invasive and non-contrast tool recently applied in several medical centers and basic research fields,131,132 as well as other new emerging technologies.133,134 Several innovative approaches are being investigated that explore the capability of HI beyond the visible range, such as intraoperative tissue recognition,135 therapeutic guidance, and monitoring126,136,137 (Fig. 4).

Experimental setup of a laser system with a thermal camera that records temperature values throughout the procedure and a hyperspectral camera. Detail of a target area after treatment136 doi:10.3390/s21020643.

Normalized variation of liver image for the 4 peculiar spectral ranges. The images are obtained with respect to the initial condition for 2 tests and for the 6 temperature thresholds.136 doi:10.3390/s21020643.

An important field of application for HI is cancer detection and in situ biopsy,138,139 along with identification of tumor boundaries for surgical guidance.140 Nowadays, microscopic (R1) or macroscopic (R2) tumor involvement in the surgical resection margins represents the main predictor of local recurrence and shortens the survival rate in various cancers.141–143 Furthermore, the current lack of commercial imaging systems that can provide intraoperative quantification of antibodies labeled for shallow cancerous lesions makes hyperspectral imaging one of the most interesting and clinically transferable tools to test.126 Furthermore, HI can be used to obtain quantitative imaging of physiological tissue parameters and visualization of anatomical structures. Other applications in surgery may be to differentiate the colon and its mesenteric tissue from the retroperitoneal tissue, obtain a correct dissection plane, or quantify intestinal ischemia by identifying physiological oxygenation of the tissue, making it an interesting tool to evaluate the perfusion of anastomoses in surgery.134,144

Conflicts of interestsProfessor Salvador Morales-Conde, Dr. Laura Navarro-Morales, Dr. Francisco Moreno-Suero, Dr. Andrea Balla and Dr. Eugenio Licardie have no conflicts of interests or financial ties to declare.

Contributions of the authorsSalvador Morales-Conde: study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, preparation of the manuscript, critical review and approval of the final version of the manuscript

Laura Navarro-Morales: study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, preparation of the manuscript, critical review and approval of the final version of the manuscript

Francisco Moreno-Suero: study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, preparation of the manuscript, critical review and approval of the final version of the manuscript

Andrea Balla: study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, preparation of the manuscript, critical review and approval of the final version of the manuscript

Eugenio Licardie: study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, preparation of the manuscript, critical review and approval of the final version of the manuscript