Artificial intelligence (AI) will power many of the tools in the armamentarium of digital surgeons. AI methods and surgical proof-of-concept flourish, but we have yet to witness clinical translation and value. Here we exemplify the potential of AI in the care pathway of colorectal cancer patients and discuss clinical, technical, and governance considerations of major importance for the safe translation of surgical AI for the benefit of our patients and practices.

La inteligencia artificial (IA) impulsará muchas de las herramientas del arsenal de los cirujanos digitales. Los métodos de IA y las pruebas de concepto quirúrgicas están floreciendo, pero aún tenemos que presenciar la traslación y el valor clínicos. Aquí ejemplificamos el potencial de la IA en la vía de atención de los pacientes con cáncer colorrectal y analizamos consideraciones clínicas, técnicas y de gobernanza de gran importancia para la traslación segura de la IA en cirugía en beneficio de nuestros pacientes y prácticas.

The ability to timely model the vast amount of digital data produced during surgical care well sets artificial intelligence (AI) to improve surgical care. Sharing this vision, in the last years several surgeons and computer scientists have joined forces in academic and industrial surgical data science groups to demonstrate the potential of data and analytics AI to positively impact the whole surgical care pathway – from screening to home-monitoring.1–3

Probably one of the most advanced use cases is colorectal cancer (CRC) (Fig. 1). Level one evidence on the value of systems that detect (computer-assisted detection, CADe) and characterize (CADx) colorectal polyps during screening colonoscopy is mounting, not only with respect to the increase in key performance indicators such as adenoma detection rate4 but also through modelling studies showing the potential of these systems to decrease costs and prevent CRC induced deaths.5 AI is also being investigated to predict the depth of invasion prior to endoscopic resection6 and the risk of lymph node metastasis after endoscopic resection of early CRC,7 so as to better identify patients that would benefit from local, endoscopic, resection and surveillance versus patients requiring surgery. In the case of endoscopic resection, AI could help safely performing endoscopic submucosal dissection, as recently shown by a proof-of-concept system automatically segmenting colonic layers and vessels to guide endoscopists.8 When surgery is needed, AI could help us stratify patients to tailor the surgical approach. For instance, models analyzing patient and disease data to predict the status of inferior mesenteric artery lymph nodes in left-sided CRC9 could inform on whether to perform a high ligation with oncological benefits or to preserve the left colic artery to reduce the risk of anastomotic leakages. Intraoperatively, AI systems approaching commercialization promise to guide surgeons toward the right plane of dissection,10,11 potentially helping preserve nerves for better functional outcomes or preventing feared ureteral injuries. Collaterally, AI systems already in clinical use might help anesthetists predict and prevent intraoperative hypotensive events.12 Postoperatively, advanced patient monitoring could provide early warnings of patients deterioration needing urgent care or fast-tracking home discharge, were patient recovery could be monitored by wearables.13,14

AI for CRC care pathway. The AI-assisted screening colonoscopy image is adapted from Hassan et al.36 The AI-assisted endoscopic resection image indicating layers and vessels is adapted from Ebigbo et al.8 The AI-based intraoperative support image suggesting dissection planes is adapted from a live demo of Eureka (Anaut, Japan) performed by Salvador Morales Conde at the XLII Curso de Actualizacion en Cirugia, February 7-9, 2024, in Seville, Spain. DSI: depth of submucosal invasion; LN: lymph node; IMAN: inferior mesenteric artery nodes.

However, it is still the early days of AI in surgery and several technical, clinical and governance considerations still need to be addressed before data and analytics show their full value to patients, surgeons, and healthcare systems.15

Here we briefly analyze open challenges and discuss possible solutions.

Clinical considerationsWe are only just starting to study surgical quality, its impact on patients’ outcomes, and how to improve it, especially for what regards the intraoperative phase of surgical care. Arguably, the need to collect and consistently analyze (i.e., annotate) surgical data such as procedural videos and relative outcomes to develop AI models is in itself showing to be the first collateral value induced by the vast interest in surgical AI. For example, while we were collecting and analyzing data to develop an AI for the automatic assessment of the critical view of safety (CVS) in cholecystectomy, we found out that this universally recommended safety step was correctly implemented in as low as 16% of the cases. Such insights led to proposing 5-second rule,16 a brief time-out to verify the CVS with assistants. In a before vs after we found out that such a simple quality improvement intervention triplicates the rate of clinical implementation of the CVS,16 suggesting a strategy to fill the guidelines to surgical practice implementation gap. However, most intraoperative events and dynamics still need to be well studied. AI can certainly help by providing quantitative analysis of data at scale, but the surgical community needs to play a central role in defining problems and solutions first. Formalizing key performance measures and indicators, a strategy used in closely related disciplines such as gastrointestinal endoscopy, and defining standard operating procedures, protocols to effectively deal with intraoperative events, could help quantitatively assess and consistently improve our practice. Only then we can develop AI to help solve real surgical problems.

AI is not a pill, and we cannot study its effect on surgical care using the same study designs optimized and popularized by pharmacological research. Most AI-based systems don’t act directly on patients, but rather act on how care is delivered. For this reason, if we were to test the effect of an AI-based quality improvement initiative on patient outcomes, performing a classical trial in which the same surgeon receives (intervention group) or doesn’t receive (control group) AI-assistance based on the randomization status of the patient would be at high risk of bias. In this specific case, a surgeon that receives AI-support for one patient and no support for the next one will likely still do better with the second patient. The effect of the intervention could spill onto the control leading to a so-called contamination bias, a typical risk of service-delivery studies. More in general, if the intervention acts on the delivery of care rather than the patient, then we should control for baseline surgeon’s characteristic and, if necessary, randomize at this stage. For the above reasons cluster randomized trials with baseline periods, a type of pragmatic study design allowing to randomize groups (i.e., clusters) of patients (e.g., all patients treated by the same surgeon, in the same department, at the same hospital, etc.) and including both a before-after and a parallel control, represent a valid study design option for AI-based interventions.17,18 Alternatively, well though-out registries recording, for instance, also if the AI-based system was utilized or if automated recommendations were followed or not, could provide evidence on the real-world and over-time value of such system.

Being an instrument in the hands of caregivers, the value of an AI-based system is intrinsically dependent on the way clinicians interact with it and use it. For instance, endoscopists might be induced into a false sense of comfort when using AI and decrease the quality of their screening colonoscopy, as suggested by pragmatic, real-world trials.19,20 In addition, AI-systems may be used differently from how manufacturers and regulators intended, as recently shown in radiology.21 Purposely defined educational initiatives targeting surgical staff willing to implement these new tools into practice could surely help. In addition, the above suggested registries as well as other monitoring initiatives could help pick up and measure usage drifts requiring continuous education or novel regulatory approvals.

Fig. 2 summarizes clinical considerations.

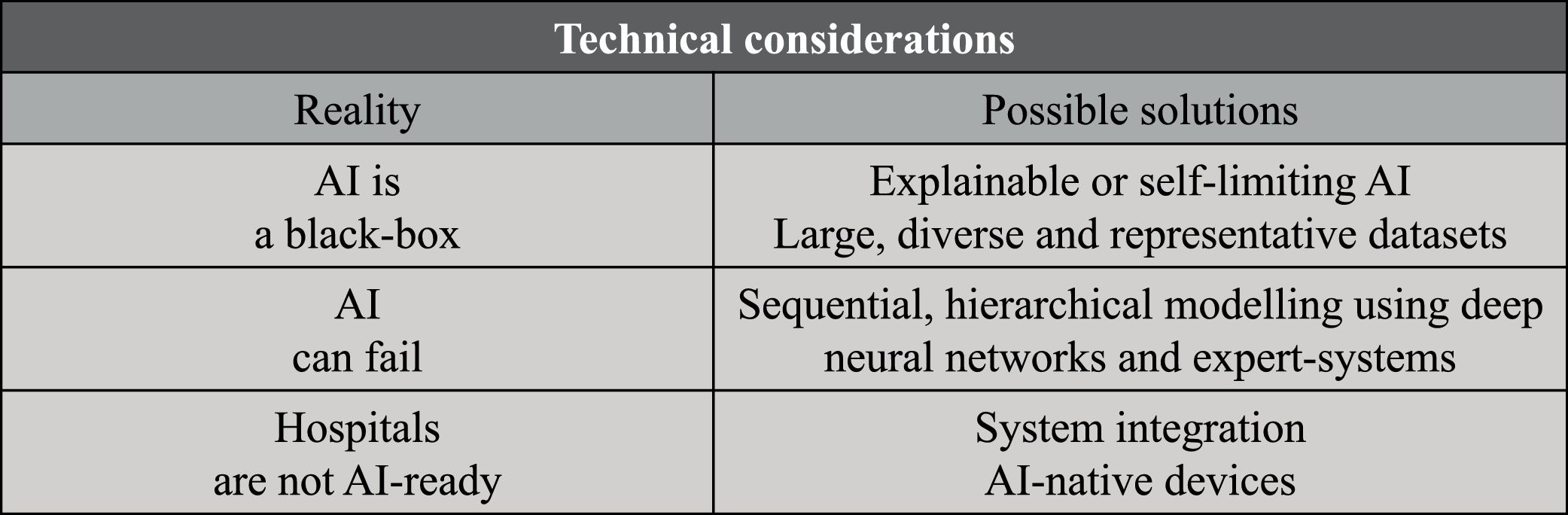

Technical considerationsAI models, especially the most sophisticated ones, are often referred to as black box. Given the high number of parameters and the intricate interplay of those, the inner working of models such as deep neural networks is hard to decode. While being a very interesting research problem, at first explainability doesn’t seem an application problem – at the end of the day, doctors and regulators often don’t know the exact mechanisms of drugs we use in every day clinical practice. However, the explainability problem is of major importance for the safe application of AI systems in clinical and surgical practices because it limits our ability to define the system’s indications and contraindications to use. As a matter of fact, it is currently hard to estimate if an AI system will work for a specific patient population or in a specific setting if the dataset used for training and testing the AI-model doesn’t represent it. The current solution is to restrict indications only to the development population. However, this is very hard to control and limits the potential of AI to prevent major but rare and underrepresented conditions. On the one hand, the computer science community is actively searching for solutions to the explainability problem22 and adding guardrails such as systems capable of flagging when they are not likely to deliver an accurate prediction.23 On the other hand, the clinical community is trying to address this problem collecting and openly sharing large, diverse, and representative datasets on which AI systems can be trained and test. For instance, with the Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) we are organizing the Critical View of Safety Challenge, an initiative collecting more than 1000 surgical videos from all over the globe and gathering clinically meaningful annotations so as to release a large and representative dataset to benchmark AI solutions for safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy (https://www.cvschallenge.org/).

AI predictions will never be 100% accurate. No matter how well we train a model, this could always fail, especially when analyzing cases not well represented in the development dataset, as discussed above. In surgery as well as in other high-stake applications of AI, inaccuracies can have high human and financial cost and risk to slow the uptake of such a powerful technology. Here, emulating how we humans tackle complex tasks could help developing a robust AI system. When facing nontrivial problems, we usually break them down into a sequence of smaller problems, cross solutions, and reason through them to solve the bigger picture. Similarly, we can design AI systems that solve problems through sequential, hierarchical modelling. Is saying, such systems would be composed by a set of AI models, each solving narrower tasks, crossing information with one another, to solve down-stream tasks. For example, if we want to build an AI to recognize surgical actions, we might want models to detect surgical tools24 and segment anatomy25 first. Surgical tool and anatomy information would then be used to model surgical actions, such as “hook dissecting the cystic duct”.26,27 In addition to simplifying the modelling, such a modular approach could allow to repurpose AI models for different surgical use cases, for instance utilizing the above surgical tool detector to infer metrics of surgical skills.28 Finally, sequential modelling could also entail using deep neural networks together with more controllable rule-based expert systems. A combination of deep and rule-based modelling was used in EndoDigest, a computer vision platform to selectively video document critical events of surgical procedures that showed good performance even when some of its AI predictions were wrong29 and when tested on very diverse data coming from 4 centers.30 Altogether, we believe that a sequential, hierarchical modelling strategy using both powerful deep neural networks and controllable expert systems might render AI system more performant, robust, scalable, and explainable.31

Most hospital information technology (IT) infrastructure and medical devices are not AI-ready. AI is computationally intensive and requires specialized hardware (e.g., graphic processing unit, GPU), especially the most powerful deep neural networks powering most of today state-of-the-art image and text applications. Furthermore, AI-powered system needs to interface with diverse hospital IT systems and/or closed, hardly interoperable, medical devices for fishing data and deliver predictions. These challenges are currently being tackled in several ways. One solution would be to add integration and compute to hospital infrastructure, a strategy enabling the full value of an integrated system but requiring major investments and buy-in (e.g., Caresyntax Integrated OR, Karl Storz OR1). On the other end of the spectrum, several players are incorporating AI capabilities in their medical devices or in stand-alone, at times vendor-neutral, units (e.g., Siemens Healthineers YSIO X.pree and Medtronic GI Genius, respectively). This approach is more rapid and could confer a market hedge, but risks hinder the full potential of digital health buy further siloing health information.

Fig. 3 summarizes technical considerations.

Governance considerationsAI models are built using patient data, not only companies’ hardware and know-how. This poses novel questions on how to promote innovations that could benefit patients and healthcare systems while preserving stakeholders’ rights, starting from patients privacy and ownership. Regulations on the management of patients’ data such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) act in the United States of America exist. However, these are not necessarily clear on the requirements for the compliant development, sharing, and use of datasets for AI development, hindering innovation that could benefit society. Researchers and companies are tackling this challenge by developing pipelines and AI methods to de-identify data and/or bypass the need to share data. Endoscopic videos guiding minimally invasive procedures are being de-identified by removing file meta-data (i.e., data included in the video file such as the day and time of the recording) and using AI models capable of detecting non-endoscopic, out-of-body images that could potentially show identifiable information (e.g., patients and staff faces, operating room clock, etc.).32,33 De-centralized approaches such as federated learning and evaluation that share models across centers rather than centralizing data are currently being studied for surgical AI development.34

Most AI-based applications of clinical utility are classified and regulated as software as medical devices (SaMD). This requires defining an intended use (i.e., the clinical scope the application serves) and providing evidence supporting safety and claims based on risk analysis and classification. Regulatory needs shouldn’t be seen as a bottleneck but as a necessary step in the clinical translation of safe and effective solutions. However, intended use doesn’t often match the actual clinical use of the AI-powered SaMD, as recently shown in radiology,21 and regulators as well as manufacturers are often intimated by the uncertainty around AI. This requires collaborations between regulators and stakeholders to guarantee efficient and transparent processes based on a common understanding of the importance of a sound audit for all stakeholder, patients as well as businesses.

Finally, a major bottleneck to the adoption of AI in clinical and surgical practices is the uncertainty around medico-legal liability. Who’s responsible for a suboptimal outcome when an AI-powered application is used? What if a surgeon follows a wrong recommendation or ignores a correct prediction? We need solid answers to these questions if we believe in the potential of AI in healthcare. While certainly law makers will clarify regulations and regulate novel situations introduced by autonomous systems, we believe that a pragmatic approach answers most of the current use cases. Current AI-powered applications in surgery as well as most AI applications in medicine do not act or make decisions autonomously, but rather estimate information with a certain degree of confidence for aiding clinical decision making and actions. This kind of assistance is comparable to that of many other non-AI medical devices routinely used to inform clinical practices. Like for classical medical devices, design choices influence the risk of AI-powered applications. For instance, if we were to use DeepCVS, an AI to assess the achievement of the critical view of safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy,35 deploying it for intraoperative guidance (i.e., DeepCVS informs when it is safe to divide the cystic duct) or an automated warning (i.e., DeepCVS warns surgeons if they attempt to divide the cystic duct when it is not safe) would entail very different risks. In the first design a wrong prediction (e.g., DeepCVS giving the green light to proceed when the critical view of safety is not achieved) could induce a bile duct injury while in the second design a wrong prediction (e.g., DeepCVS warning the surgeon when the critical view of safety is actually achieved) could, at worst, slightly increase procedural times.

Fig. 4 summarizes governance considerations.

Re-imagining surgery togetherWhile surely incomplete, we hope that the above clinical, technical, and governance considerations could help spark discussions in the surgical data science community. Together with the continued identification of new surgical use cases, development of AI methods, and proof-of-concept of surgical AI applications, we believe such multidisciplinary discussions will get as closer to revealing the true value of AI applications in surgery.