Traumatic abdominal wall hernia (TAWH) is a protrusion of contents through a defect in the abdominal wall as a consequence of a blunt injury. The objective of this review was to describe demographic and clinical aspects of this rare pathology, identifying the optimal moment for surgical intervention, evaluating the need to use mesh, and analyzing the effectiveness of surgical treatment. Thus, a systematic review using PubMed, Embase, and Scopus databases was carried out between January 2004 and March 2024. Computed tomography is the gold-standard imaging test for diagnosis. Open surgery is generally the preferred approach, particularly in emergencies. Acute TAWH can be treated by primary suture or mesh repair, depending on local conditions, while late cases usually require mesh.

La hernia traumática de la pared abdominal (HTPA) es una protrusión de contenido a través de un defecto en la pared abdominal como consecuencia de una lesión contusa. El objetivo de esta revisión fue describir aspectos demográficos y clínicos de esta patología poco frecuente, identificando el momento óptimo para la intervención quirúrgica, evaluar la necesidad de utilizar mallas y analizar la efectividad del tratamiento quirúrgico. Para ello se realizó una revisión sistemática de las bases de datos de PubMed, Embase y Scopus de estudios publicados entre enero de 2004 y marzo de 2024. La tomografía computarizada es el estándar para su diagnóstico. La cirugía abierta es el abordaje de elección. La HTPA aguda se puede tratar mediante reparación primaria con sutura o malla, dependiendo de las condiciones locales, mientras que los casos tardíos generalmente requieren colocación de malla.

Traumatic abdominal injuries are a significant public health problem worldwide, causing a considerable number of visits to emergency departments.1

Blunt trauma can cause a tear in the abdominal muscles, leading to traumatic abdominal wall hernia (TAWH). Traumatic hernia is a type of acquired hernia that arises after musculofascial rupture caused by direct, non-penetrating trauma, with no prior evidence of hernia at the affected site.1,2 Occurring in less than 1% of trauma patients,3 these hernias are rare and challenging for surgeons. They can originate in the anterior, lateral or posterior wall of the abdomen, and even in the inguinal region due to their close anatomical relationship.

The presentation of traumatic hernia is usually acute, although in some cases it can manifest late, which emphasizes the importance of high clinical suspicion. Clinical manifestations vary depending on the hernia size and content, whether it is complicated or not, and any associated injuries. These hernias are frequently associated with a high percentage of intra-abdominal injuries requiring urgent laparotomy or laparoscopy, prioritizing the resolution of these injuries over hernia repair.2 However, as high recurrence rates have been reported in cases with immediate traumatic hernia repair,4–6 there is a demonstrated need to promptly assess trauma-related hernias and determine the optimal timing for surgical intervention. Even so, there is currently limited evidence available to guide the timing of surgical intervention or the feasibility of non-surgical treatment.7

The objectives of this review are to describe the demographic and clinical aspects of this rare pathology and to address the essential elements of traumatic hernia treatment, identifying the optimal moment for intervention, evaluating the need for mesh, and analyzing the effectiveness of surgical treatment.

MethodsWe have conducted a systematic review of the literature using the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses) guidelines8 and the Pubmed, Scopus and Embase databases. The search was limited to articles of observational studies published in English and Spanish between January 2004 and March 2024 with the objective of evaluating articles that were relatively similar in terms of techniques and materials. The keywords traumatic hernia were used in combination with the abdominal, lumbar and inguinal locations. Duplicate publications were identified and removed using an automated program (Covidence(R); Melbourne VIC 3000, Australia).9

Subsequently, the articles were evaluated manually and selected, excluding studies related to traumatic hernias in other locations, publications in languages other than Spanish or English, articles whose full text could not be accessed, and individual case reports. Two authors (JDF and JMG) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all the articles from the initial search to identify articles for full-text review, and any discrepancies were arbitrated by all authors. Articles describing abdominal hernias secondary to penetrating injury were excluded.

The data extracted from each selected study included demographic data (age, sex), clinical presentation, hernia characteristics (location, side), preoperative diagnostic tests (ultrasound, computed tomography), associated injuries, surgery type (immediate, acute, delayed or deferred surgery),6 approach (open or laparoscopic), type of repair (use of mesh), as well as postoperative data (mortality, morbidity, recurrence). A repair was considered acute when it was performed less than 2 weeks after the initial trauma. Repair at a later stage was considered deferred.

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were expressed as frequencies or percentages. Subgroup comparisons were planned (adult and pediatric population, acute versus delayed repair, open or laparoscopic approach, mesh repair and primary repair). This paper was limited to a descriptive statistical study of the available evidence.

ResultsSystematic reviewA total of 1285 articles were identified in the search of the literature (678 in PubMed, 486 in Scopus, and 121 in Embase). After discarding 391 duplicate references, we analyzed the titles and abstracts of 894 publications, excluding 685 references that were not relevant to the study topic. Among the resulting 209 publications, 192 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). After discarding the studies that met the exclusion criteria, 17 articles were included in this systematic review (Table 1).

Demographics by author, sex and age.

| Author and age | Study design | Number of patients | Males | Females | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Netto et al. (2006)18 | Retrospective cohort | 34 | 19 | 15 | 39 (±12) |

| Bender et al. (2008)4 | Prospective cohort | 25 | 10 | 15 | 36.4 (13–66) |

| Gupta et al. (2011)33 | Cases series | 11 | 8 | 3 | 42.4 (ND) |

| Gutteridge et al. (2014)34 | Cases series | 5 | 3 | 2 | 30 (20–59) |

| Honaker et al. (2014)2 | Retrospective cohort | 38 | 23 | 15 | 35.8 (±20.1) |

| Talutis et al. (2015)32 | Retrospective cohort | 5 | 3 | 2 | 7 (4–11) |

| Coleman et al. (2016)6 | Retrospective cohort | 80 | 50 | 30 | 38.6 (9–81) |

| Pardhan et al. (2016)25 | Retrospective cohort | 44 | 30 | 14 | 36 (RIC 24–54) |

| Chan et al. (2017)28 | Cases series | 4 | 1 | 3 | 42 (20–52) |

| Park et al. (2018)15 | Retrospective cohort | 9 | 5 | 4 | 55 (23–71) |

| Alhadeedi et al. (2021)16 | Prospective cohort | 12 | 4 | 8 | 35.9 (16–65) |

| Hafezi et al. (2021)19 | Retrospective cohort | 11 | 8 | 3 | 10.0 (±2.1) |

| Harrell et al. (2021)7 | Retrospective cohort | 281 | 160 | 121 | 38.65 (±18.06) |

| Wong et al. (2022)22 | Retrospective cohort | 47 | 21 | 26 | 46 (31.6–60.5) |

| Abo-Alhassan et al. (2022)10 | Retrospective cohort | 6 | 4 | 2 | 28 (11–70) |

| VanNess et al. (2023)20 | Retrospective cohort | 19 | 11 | 8 | 10.6 (3–17) |

| Santos et al. (2023)26 | Retrospective cohort | 64 | 42 | 22 | 35 (7–29) |

| 695 | 402 (57.8%) | 293 (42.2%) | 33.3 (±13) |

NA: not available; SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range.

Most of the studies analyzed focused on adult populations (n = 14; 82.4%), while 3 (17.6%) described pediatric populations. In total, 695 patients were identified with abdominal hernia secondary to blunt trauma, with an incidence of 0.4%. Among these patients, 660 were adults (95%), and 35 were pediatric patients (5%), with an incidence in both groups of 0.46% and 0.12%, respectively. Demographic data showed a mean age of 33.3 years (SD ± 13). The distribution by sex revealed a majority of male patients: 402 men (57.8%), and 293 women (42.2%) (Table 1).

Mechanism of injuryIn the analysis of the mechanism of injury, a predominance of automobile accidents was observed (n = 459; 66%), followed by motorcycle accidents (n = 64; 9.2%). Regarding falls and pedestrians being struck by vehicles, traumatic hernias were observed in 41 (5.9%) and 36 (5.2%) patients, respectively; 24 patients (3.5%) were diagnosed with a secondary handlebar injury, while 29 (4.2%) patients presented other mechanisms. In 42 patients (6%), the mechanism of injury was not recorded (Fig. 2).

External and associated injuriesThe most common external injury was the seat-belt sign, which was present in 60 patients (8.6%). Thirteen patients (1.9%) had an abdominal mass, 12 (1.7%) of which were reducible and one (0.1%) irreducible. Four (0.6%) patients had evisceration of intra-abdominal contents.

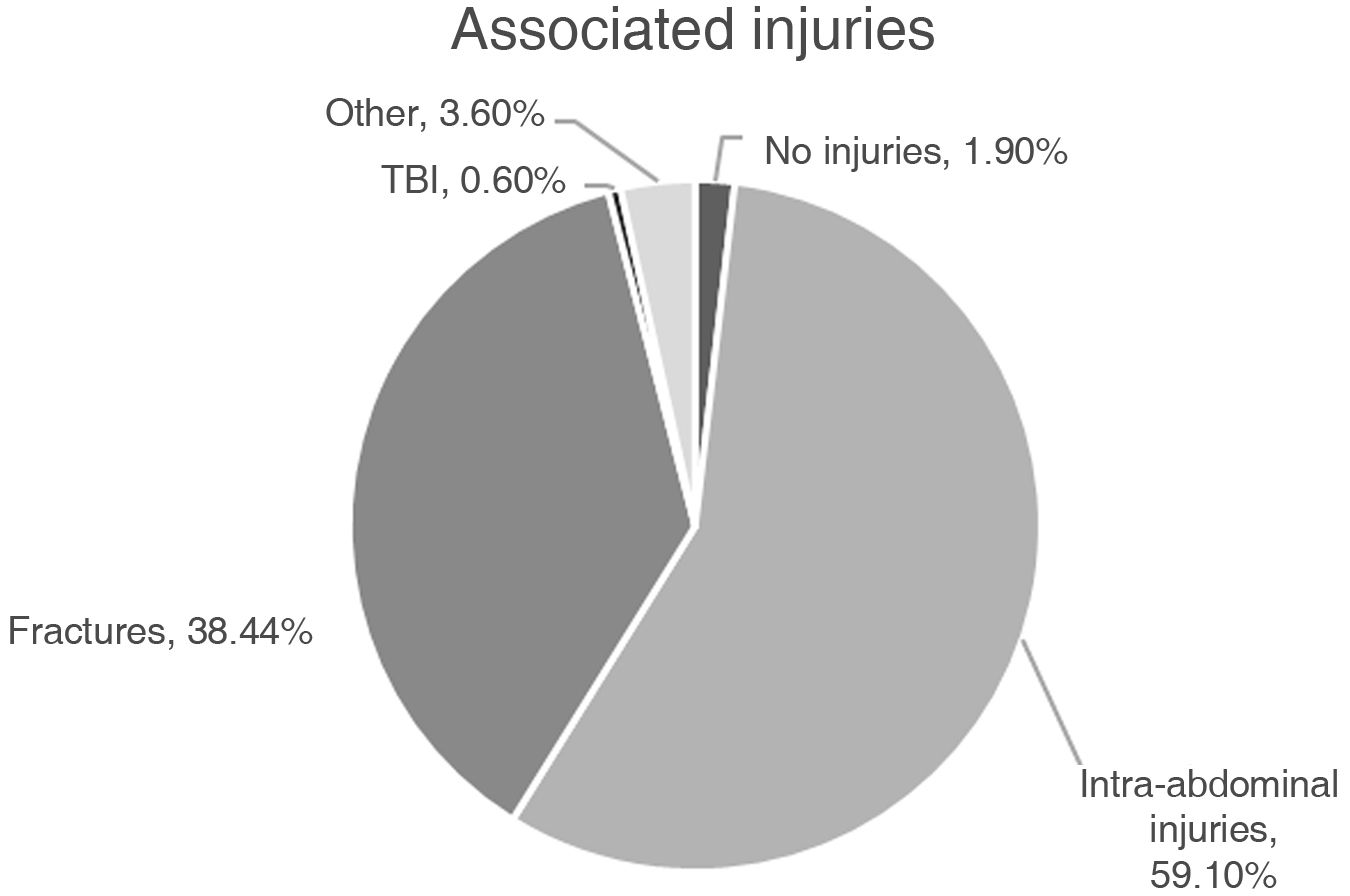

As in any mechanism of blunt trauma, these patients present more than one type of associated injury. In this study, 411 (59.1%) patients presented intra-abdominal injuries, the most frequent being solid organs (spleen and liver), mesentery, small intestine and colon, followed by 267 (38.4%) patients with bone fractures. Among the 267 (14.7%) patients who presented a fracture, there was a predominance of vertebral fractures (n = 113; 16.3%), followed by pelvic (n = 96; 13.8%), long bone (n = 48; 6.9%) and ribcage (n = 10; 1.4%) fractures. Thirteen (1.9%) patients did not present injuries (Fig. 3, Table 2).

Associated injuries.

| TOTAL | n (%) = 695 |

|---|---|

| Patients without injuries | 13 (1.9) |

| Intraabdominal | 411 (59.1) |

| Intestinal injuries | 250 (36) |

| Mesentery | 76 (10.9) |

| Small intestine | 38 (5.5) |

| Colon | 37 (5.3) |

| Not described | 99 (14.2) |

| Organ injuries | 102 (14.7) |

| Spleen | 39 (5.6) |

| Liver | 27 (3.9) |

| Genitourinary | 26 (3.7) |

| Vascular | 5 (0.7) |

| Diaphragm | 4 (0.6) |

| Not described | 1 (0.1) |

| Fractures | 267 (38.4) |

| Vertebra | 113 (16.3) |

| Pelvis | 96 (13.8) |

| Long bones | 48 (6.9) |

| Rib | 10 (1.4) |

| Traumatic brain injury | 4 (0.6) |

| Other | 25 (3.6) |

For the diagnosis of traumatic hernia, computed tomography was performed in 543 patients (78.1%), intraoperatively in 42 (6%) patients, and a single pediatric patient was diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging (0.1%). In 109 (15.7%) patients, the diagnostic method was not recorded.

Regarding the location of the 690 traumatic hernias, the most prevalent distribution was in the anterior region of the abdominal wall (n = 281; 40.7%), followed by the lateral region (n = 220; 31.9%) and the lumbar/posterior region (n = 189; 27.4%). No traumatic hernias were recorded in the inguinal region. More details are provided in Table 3.

TreatmentIn 517 (74.4%) patients, the decision was made to operate on the traumatic hernia. In 178 (25.6%) patients, non-surgical management was chosen (Table 4).

Treatment of traumatic hernias.

| Treatment of traumatic hernia | n (%) = 695 |

|---|---|

| Surgical | 517 (74.4) |

| Non-surgical | 178 (25.6) |

| Surgical approach | n (%) = 517 |

| Open | 300 (58) |

| LPC | 21 (4.1) |

| Conversion | 4 (0.8) |

| Robot | 3 (0.6) |

| Not registered | 189 (36.6) |

| Repair time | n (%) = 517 |

| Immediate | 226 (43.7) |

| Acute (< 2 weeks) | 209 (40.4) |

| Deferred/Elective (>2 weeks) | 104 (20.1) |

| Use of mesh | n (%) = 517 |

| No | 289 (55.9) |

| Yes | 148 (28.6) |

| Synthetic non-absorbable | 31 (21) |

| Biologic | 30 (20) |

| Synthetic absorbable | 9 (6) |

| Mixed | 4 (3) |

| Not described | 74 (50) |

| Not registered | 80 (15.5) |

The most common surgical approach was open (n = 300; 58%), followed by laparoscopic (n = 21; 4.1%); 4 (0.8%) were converted to open surgery, and the robot-assisted approach was used in 3 (0.6%) patients.

In 226 (43.7%) patients, surgery was immediately performed in the initial intervention, while 209 (40.4%) patients underwent surgery within 2 weeks of the event. Deferred/elective management was selected in 104 (20.1%) patients.

Mesh placement was not used in 289 patients (55.9%), while mesh was used as reinforcement in 148 (28.6%) patients: 31 (21%) non-absorbable synthetic; 30 (20%) biological; 9 (6%) absorbable synthetic; 4 (3%) mixed; and in 74 (50) patients the mesh used was not specified. In 80 (15.5%) patients, the use of mesh was not recorded (Table 4).

ComplicationsA total of 53 (7.5%) patients presented surgical complications, all belonging to the adult population and secondary to the associated injuries. Most of these complications were surgical site infection (n = 30; 5.68%), followed by intestinal ischemia, intestinal perforation, and sepsis (3 [0.6%] patients each); early incisional hernia, seroma, pancreatic lesions, fistula or anastomotic failure (2 [0.4%] patients); and internal hernia, hematoma, AMI, and thromboembolic disease (one [0.2%] patient).

During follow-up, hernia recurrence was registered in 50 (7.2%) adult patients. A total of 39 (5.5%) deaths were recorded, although none were directly related to the presence of traumatic hernia (Table 5).

Complications registered.

| Post-operative complications | n (%) = 517 |

|---|---|

| Recurrence | 50 (9.6) |

| Mortality | 39 (7.5) |

| Complications | 53 (10.2) |

| Surgical site infection | 30 (5.68) |

| Intestinal ischemia | 3 (0.6) |

| Intestinal perforation | 3 (0.6) |

| Sepsis | 3 (0.6) |

| Incisional hernia | 2 (0.4) |

| Seroma | 2 (0.4) |

| Fistula | 2 (0.4) |

| Anastomotic failure | 2 (0.4) |

| Pancreatic injury | 2 (0.4) |

| AMI | 1 (0.2) |

| Hernia interna | 1 (0.2) |

| Hematoma | 1 (0.2) |

| PTE/DVT | 1 (0.2) |

AMI: acute myocardial infarction; PTE/DVT: pulmonary thromboembolism/deep vein thrombosis.

With a reported incidence of less than 1%,3 TAWH are rare lesions, and their treatment is challenging for surgeons. These hernias arise from injury to the musculofascial structures of the abdominal wall with skin integrity, resulting from the transfer of energy from an object or trauma injury over a small area, causing a defect in said structure.10,11 To individualize the management of these patients, we must consider the type of patient affected, mechanism of injury, associated injuries, location and characteristics of the hernia. Other factors are debated in the literature, for instance the need for hernia repair, the most appropriate time for this repair, and whether prosthetic mesh is needed.5,12

Demographic variablesThis review describes an incidence of traumatic hernia of 0.4%, which coincides with the <1% rate reported in the literature. Furthermore, the incidence of patients at risk of future hernia formation is 1.5%.13

Our review of the literature found that traumatic hernia is more common in the adult population than in the pediatric population, with an incidence of 0.46% and 0.12%, respectively. The average age of presentation is in the third decade of life, with a slight predominance of the male sex.

Mechanism of injury, location pattern and associated injuriesBoth high- and low-energy trauma can cause a traumatic hernia. In this study, the high-energy trauma events were traffic accidents, and motor vehicle accidents were the main mechanism of injury. Moreno Egea et al.5 classified traumatic hernias related to traffic accident types: A) non-motorized vehicles; B) low-powered vehicles; and C) high-powered vehicles.

Damage to the abdominal wall occurs through 3 main mechanisms described in the literature11–13:

- 1

Blunt, direct force on the abdominal wall. This force is capable of damaging the musculofascial structures but is not sufficient to break the skin. In handlebar hernias, for example, the force is applied directly to the abdominal wall, and the hernia appears at the trauma injury site.14 We must also consider that blunt force is also transmitted to the intra-abdominal organs, and associated injuries may be found in more than half of patients (59.1%). Among these, the most frequent are usually intestinal or solid-organ injuries.

- 2

Sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure with transmission of energy to pre-existing areas of anatomical weakness. Traumatic hernias tend to appear more frequently in areas of anatomical weakness. The location pattern is usually related to the type of trauma injury. However, the low incidence of reports of traumatic inguinal hernias is striking. The most common location is the anterior abdominal wall and midline (40.7%), mainly in the lower quadrants. The supraumbilical location is rare, possibly due to the reinforcement of the posterior sheath of the anterior rectum at this level.5 Sometimes the location of the hernia defect does not coincide with the initial impact site. This occurs in traumatic lumbar hernias caused by high-energy injuries. The inferior lumbar triangle (Petit triangle) is the site of presentation for 70%, while the remaining 30% are located in the superior lumbar triangle (Grynfeltt-Lesshaft triangle).15,16

- 3

Acceleration/deceleration movements added to the compressive force of an object, such as the seat belt. Deceleration forces are associated with a higher incidence of mesentery injuries, especially in patients with a high body mass index (BMI). It has been reported that obesity could be a crucial risk factor for developing traumatic abdominal wall hernia.17 The seat-belt mark was the most frequent external injury (60 patients). There is a reported association between the presence of the belt mark in patients with the presence of a traumatic hernia.18 This could be more related to the speed of impact since belt marks are frequent in high-speed mechanisms of injury.

The diagnosis is made in the secondary assessment mainly through physical examination, associated imaging tests or as an intraoperative finding. The imaging test used in most patients was computed tomography (CT). Dennis et al.13 created a numerical classification system from I to VI based on the radiological findings and characteristics of the musculofascial injuries of the hernia and its contents for the purpose of grading the severity of traumatic hernias. It is important to keep in mind that a hernia that is small or posterior may be missed on physical examination and may not even be detected on the initial CT scan.19 The presence of a traumatic abdominal wall hernia has been described as indicative of the coexistence of associated injuries. Therefore, it is important to maintain a high index of suspicion to diagnose intestinal, mesenteric, and pancreatic injuries. Any patient with traumatic abdominal wall hernia detected by CT should be carefully evaluated, especially in the context of a motor vehicle collision.20,21

TreatmentTreatment of traumatic hernia should be individualized and based on patient characteristics using targeted algorithms, which could lead to lower morbidity, mortality, costs and hospital stay.22,23 In our study, we reported surgical treatment of traumatic hernia in the majority of patients (74.4%), while conservative management was preferred in 33.2%.

The controversies found in the literature refer to the indications for surgery and the ideal timing of traumatic hernia repair.5 The timing of surgical intervention on any TAWH should be decided while considering the mechanism of trauma, wall defect, clinical and radiological findings, associated injuries, and clinical status of the patient.22,24–26

Emergency surgery is recommended when the patient presents symptoms and signs of hemodynamic instability, associated injuries that do not allow delay, or strangulation of the hernia contents.5,22,27 On the other hand, delayed management avoids an extensive incision and allows for direct repair on stable tissues.12,28 The optimal repair time is a topic of debate and there is currently no consensus for its management. Coleman and colleagues6 grouped the timing of traumatic hernia repair into 2 periods: acute repair (during the first 2 weeks) and deferred repair (greater than 2 weeks). In this study, we found that the hernia is repaired immediately in 43.7% of cases. Traumatic hernia repair times could be summarized as follows:

- -

Immediate repair: within 24 h after the trauma injury. The patient either presents signs of obstruction or strangulation of the hernia contents, or there are associated injuries that do not allow for delay. In addition, the patient benefits from immediate hernia repair.

- -

Acute repair: during the first 2 weeks after the trauma, coinciding with the initial hospital admission or after stabilizing and optimizing the patient.

- -

Deferred repair: elective procedure at least 2 weeks after the trauma injury

- -

Late repair: when the repair occurs years after the trauma

Early repair (if the patient’s condition allows) and delayed repair seem to be safe and correct approaches in these patients.24,29

The surgical approach can be open, laparoscopic or robotic. Open surgery is used in most cases, and it is also conducted in the context of an emergency. In our study of the 517 surgical patients, 300 (58%) underwent open surgery. Laparoscopic and robotic approaches are relegated to deferred surgery. During surgical exploration, damage to the musculofascial structures is confirmed, and associated injuries are identified. Nonviable tissue and muscle should be debrided. The type of repair can be a primary repair with reinforcement of the abdominal wall using sutures, placement of an absorbable or non-absorbable mesh, or biological material.5,30–33

In this study, primary closure was the most common (55.9% of cases), and prosthetic repair was performed in only one-third of patients. The presence of intra-abdominal contamination resulting from intestinal injury is usually a determining factor for not using prosthetic mesh, or for deferring surgical repair of the defect. Consequently, if the defect is large and there is no contamination, closure should be performed with mesh. Another factor to consider when selecting the repair type is hemodynamic instability secondary to hemorrhage from injured vessels or solid organs.

There are very few descriptions of postoperative surgical complications after traumatic hernia repair, and none are recorded uniformly. The most frequent complication is recurrence (7.2% of patients), which is apparently related to the primary repair of the defect. Mortality related to this type of procedure is described in 5.5% of the analyzed sample. This mortality rate is influenced by the context of polytrauma patients and resulting comorbidities.19

Limitations of the studyThis study has several limitations: 1) it is a systematic review of mostly retrospective- articles, as traumatic hernia is a rare entity; 2) some articles do not describe all the data in a homogeneous manner, and some studies do not describe the mechanism of injury, presence of external injuries, method of diagnosis, surgical approach, or use of prosthetic mesh; 3) given the scarcity of data available, a descriptive statistical approach was followed; subgroup analyses were not feasible (adult and pediatric population, acute and late repair, open and laparoscopic repair, mesh and suture repair); therefore, inevitably, no solid recommendations can be offered.

ConclusionsTraumatic abdominal hernia is a rare entity. Surgeons treating patients with blunt abdominal trauma should consider the possibility of traumatic hernia of the abdominal wall and associated injuries.

This study highlights the importance of early diagnosis, for which computed tomography is the gold standard, and a therapeutic approach that targets patient needs. Open surgery is generally the preferred approach, particularly in emergency situations. Acute traumatic abdominal hernia can be treated by primary repair with suture or mesh, depending on local conditions, while late cases usually require mesh.

The creation of an international multicenter registry is recommended to refine treatment strategies and improve outcomes in patients with traumatic abdominal wall hernias.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.