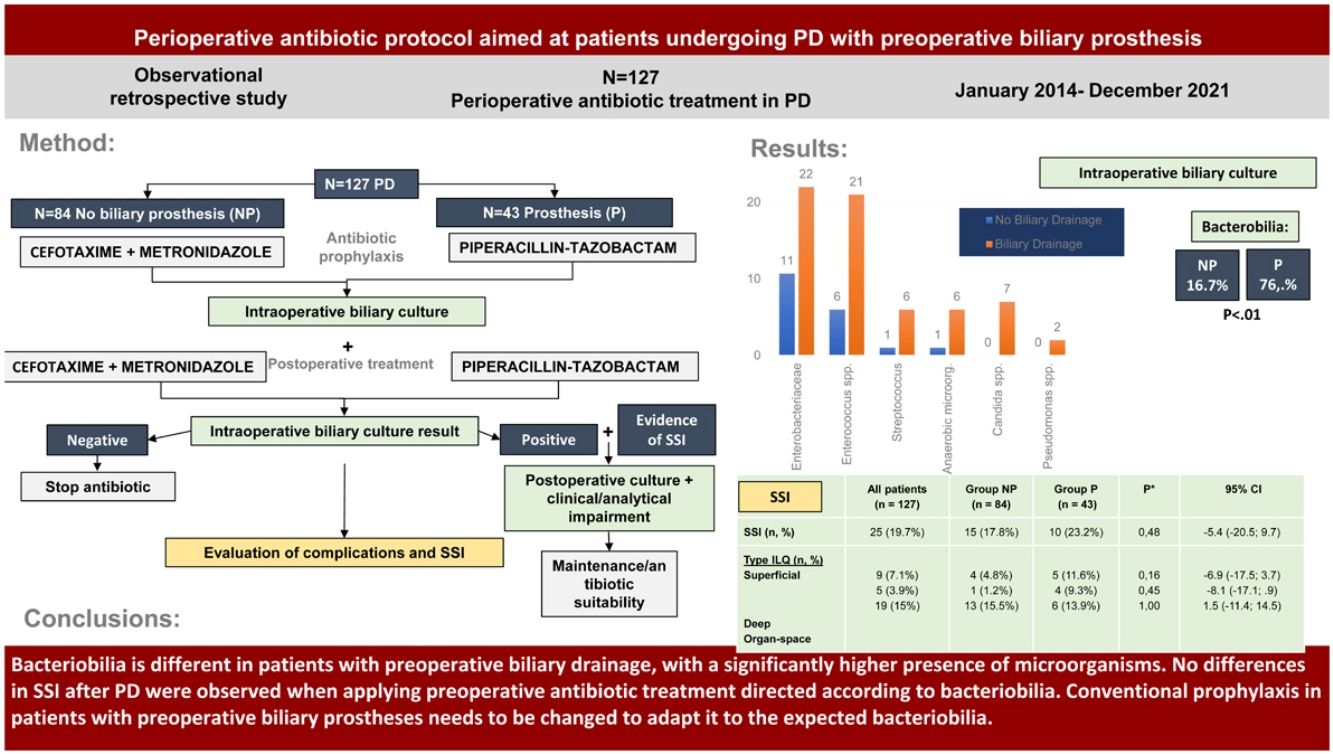

To evaluate the bacterobilia in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) based on whether they carry a preoperative biliary drainage or not and to analyse if a targeted perioperative antibiotic treatment based on the expected microbiology leads in no differences in Surgical Site Infections (SSI) between the groups.

MethodsRetrospective observational single-center study of patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy with preoperative biliary stent (group P, Prosthesis) and without stent (group NP, No Prosthesis). Postoperative complications including SSI and its subtypes were analyzed after applying a targeted perioperative antibiotic treatment protocol with cefotaxime and metronidazole (group NP) and piperacillin-tazobactam (group P).

ResultsBetween January 2014 and December 2021, 127 patients were treated (84 in group NP and 43 in group P). Intraoperative cultures were positive in 16.7% (group NP) vs 76.7% (group P, p < 0.01). Microorganisms isolated in group NP included Enterobacterales (10.7%) and Enterococcus spp. (7.1%) with no Candida detected. In group P: Enterobacterales (51.2%), Enterococcus spp. (48.8%), and Candida (16.3%) were higher (p < 0.01%). No differences in morbidity and mortality were observed between the groups. SSI rate was 17.8% in group NP and 23.2% in group P (ns).

ConclusionBacterobilia differs in patients with biliary drainage, showing a higher presence of Enterobacterales, Enterococcus spp., and Candida. There were no differences in SSI incidence after applying perioperative antibiotic treatment tailored to the expected microorganisms in each group. This raises the need to reconsider conventional surgical prophylaxis in patients with biliary stent.

Evaluar la bacteriobilia de pacientes intervenidos de duodenopancreatectomia cefálica (DPC) con y sin prótesis biliar preoperatoria y, analizar si un tratamiento antibiótico perioperatorio dirigido en función de la microbiología esperada permite no mostrar diferencias en la Infección de Localización Quirúrgica (ILQ) entre grupos.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo observacional unicéntrico de pacientes intervenidos de DPC con prótesis biliar preoperatoria (grupo P) y sin prótesis (grupo NP). Se analizaron las complicaciones postoperatorias incluyendo la ILQ y sus subtipos tras aplicar un protocolo de tratamiento antibiótico perioperatorio dirigido con cefotaxima y metronidazol (grupo NP) y piperacilina-tazobactam (grupo P).

ResultadosEntre enero de 2014 y diciembre de 2021, se trataron 127 pacientes (84 en el grupo NP y 43 en el grupo P). El cultivo intraoperatorio fue positivo en un 16,7% (grupo NP) vs un 76,7% (grupo P, p < 0,01). Los microorganismos aislados en el grupo NP fueronEnterobacterales (10,7%) y Enterococcus spp. (7,1%) sin encontrar Candida. En el grupo P: Enterococcus spp. (48,8%), Enterobacterales (51,2%) y Candida (16,3%) fueron más altos (p < 0,01%). No se detectaron diferencias en la morbilidad y mortalidad entre los grupos. La ILQ fue del 17,8% en el grupo NP y del 23,2% en el grupo P (ns).

ConclusiónLa bacterobilia es diferente en aquellos pacientes con drenaje biliar con una mayor presencia deEnterobacterales, Enterococcus spp. y Candida. No hubo diferencias en la incidencia de ILQ después de aplicar el tratamiento antibiótico perioperatorio dirigido a los microorganismos esperados en cada grupo. Se plantea la necesidad de cambiar la profilaxis quirúrgica convencional en los pacientes portadores de prótesis biliar.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is still associated with high morbidity.1,2 It is often necessary to drain the bile duct before surgery3 and manipulation of the bile duct is associated with increased bacteriobilia.4,5 This may influence surgical site infection (SSI)6 and consequently morbidity and mortality.7,8

Antibiotic prophylaxis is key to SSI control. Some authors suggest extending antibiotic coverage in PD9 or the duration of treatment.10

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the bacteriobilia of patients undergoing PD with and without preoperative biliary stents and to analyse whether a perioperative antibiotic treatment directed according to the expected microbiology led to no evidence of differences in SSI between groups.

MethodsA retrospective observational study was conducted in patients who underwent PD for malignant causes (pancreatic head neoplasms, distal cholangiocarcinomas or periampullary tumour) or benign causes (chronic pancreatitis). They were divided into two groups: those who required preoperative biliary prosthesis by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (group P, Prosthesis) and those who did not (group NP, No Prosthesis).

The indications for ERCP were: 1-Neoplasia with obstructive jaundice (total bilirubin > 15 mg/dL) with or without associated cholangitis; 2-Resectable borderline pancreatic head neoplasms eligible for neoadjuvant treatment with some degree of cholestasis and 3-Chronic pancreatitis with bile duct stenosis. These indications are based on the European Endoscopy Guidelines.11

The sample calculation (45 patients per group) was based on the study by Donald et al.,9 to detect differences of 10% in the NP group and 35% in the P group (alpha risk of .05 and lower beta .2), including twice as many patients in the NP group (90), due to having a lower risk of bacterobilia. Demographic, surgical and postoperative complication variables including SSI were collected.

Perioperative antibiotic treatmentThe antibiotic was administered during anaesthetic induction, with re-dosing 3 h after the start of surgery and maintained for 5 days every 8 h until intraoperative cultures were obtained.

The NP group received cefotaxime 2 g IV and metronidazole 500 mg IV (according to the recommendations of our centre based on regional12 and national13 guidelines) and the P group received piperacillin-tazobactam 4.5 g IV (based on the study by Donald et al.9).

In cases of penicillin allergy, they received gentamicin 240 mg IV and metronidazole 500 mg IV (NP group) and tigecycline 100 mg IV (P group).

After sectioning the common hepatic duct, 5 cm3 of bile were obtained for aerobic and anaerobic microbiological culture.

Treatment was interrupted on the fifth day when the cultures were negative and in cases of positive cultures without signs of infection or acute phase reactants (CRP < 100 mg/L, lactate <1.7 mmol/L, procalcitonin <2 μg/L). In case of infection, with positive postoperative cultures of the surgical wound or of an intra-abdominal collection, the treatment was adjusted according to the antibiogram until clinical (absence of fever) and analytical (decrease in leukocytosis and acute phase reactants) improvement.

Postoperative complications and SSIMedical and surgical complications were recorded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification14 and the Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI).15

SSI was classified as superficial, deep and organ-space.16 Pancreatic fistula,17 biliary fistula,18 delayed gastric emptying,19 and post-pancreatectomy haemorrhage20 were defined according to the different definitions of the International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Postoperative mortality was recorded at 30 and 90 days. Postoperative cultures of SSI were compared with Intraoperative bile cultures.

Signed consent was obtained from the patients and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our centre (0/21-043).

Statistical analysisQuantitative variables are expressed as median and interquartile range values, and categorical variables are expressed as absolute numbers and percentages. Quantitative variables were analysed using the Student t-test or Mann-Whitney U test if they did not follow normality after applying the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and for categorical variables, the Pearson Chi2 test or Fisher's exact test. For the multivariate study for the SSI variable, the logistic regression model was used for categorical variables. Statistical significance was established for a value of p < .05 together with the 95% confidence interval, when indicated. The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 25 programme.

ResultsBaseline and clinical patient characteristicsBetween January 2014 and December 2021, 135 patients underwent PD. After losing 8 due to incomplete samples, 127 patients with intraoperative bile culture (IBC) remained, including 84 (66.1%) in the NP group and 43 (33.8%) in the P group.

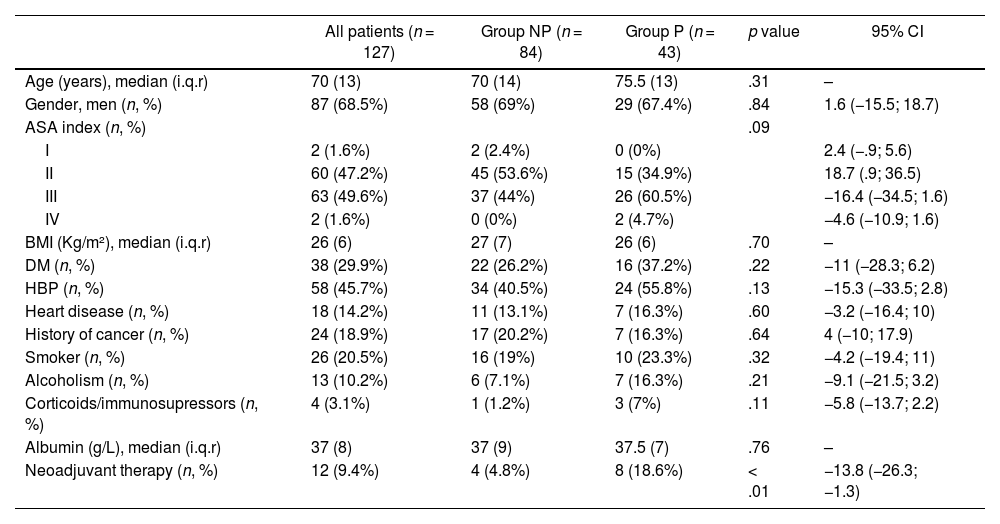

Demographic data and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. The groups were homogeneous in all variables except neoadjuvant treatment (p < .01) given the greater need for preoperative drainage in these patients to perform the treatment.

Demographic and clinical data of the series

| All patients (n = 127) | Group NP (n = 84) | Group P (n = 43) | p value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (i.q.r) | 70 (13) | 70 (14) | 75.5 (13) | .31 | – |

| Gender, men (n, %) | 87 (68.5%) | 58 (69%) | 29 (67.4%) | .84 | 1.6 (−15.5; 18.7) |

| ASA index (n, %) | .09 | ||||

| I | 2 (1.6%) | 2 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) | 2.4 (−.9; 5.6) | |

| II | 60 (47.2%) | 45 (53.6%) | 15 (34.9%) | 18.7 (.9; 36.5) | |

| III | 63 (49.6%) | 37 (44%) | 26 (60.5%) | −16.4 (−34.5; 1.6) | |

| IV | 2 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4.7%) | −4.6 (−10.9; 1.6) | |

| BMI (Kg/m²), median (i.q.r) | 26 (6) | 27 (7) | 26 (6) | .70 | – |

| DM (n, %) | 38 (29.9%) | 22 (26.2%) | 16 (37.2%) | .22 | −11 (−28.3; 6.2) |

| HBP (n, %) | 58 (45.7%) | 34 (40.5%) | 24 (55.8%) | .13 | −15.3 (−33.5; 2.8) |

| Heart disease (n, %) | 18 (14.2%) | 11 (13.1%) | 7 (16.3%) | .60 | −3.2 (−16.4; 10) |

| History of cancer (n, %) | 24 (18.9%) | 17 (20.2%) | 7 (16.3%) | .64 | 4 (−10; 17.9) |

| Smoker (n, %) | 26 (20.5%) | 16 (19%) | 10 (23.3%) | .32 | −4.2 (−19.4; 11) |

| Alcoholism (n, %) | 13 (10.2%) | 6 (7.1%) | 7 (16.3%) | .21 | −9.1 (−21.5; 3.2) |

| Corticoids/immunosupressors (n, %) | 4 (3.1%) | 1 (1.2%) | 3 (7%) | .11 | −5.8 (−13.7; 2.2) |

| Albumin (g/L), median (i.q.r) | 37 (8) | 37 (9) | 37.5 (7) | .76 | – |

| Neoadjuvant therapy (n, %) | 12 (9.4%) | 4 (4.8%) | 8 (18.6%) | < .01 | −13.8 (−26.3; −1.3) |

NP: No prosthesis; P: Prosthesis; p value: comparison between group NP and P; i.q.r: interquartile range; ASA: American Society of Anaesthesiologists; BMI: body mass index; DM: Diabetes Mellitus; HBP: High blood pressure. Chi square test for qualitative variables, Student's T for quantitative variables and Mann Whitney U for quantitative variables that do not follow normality.

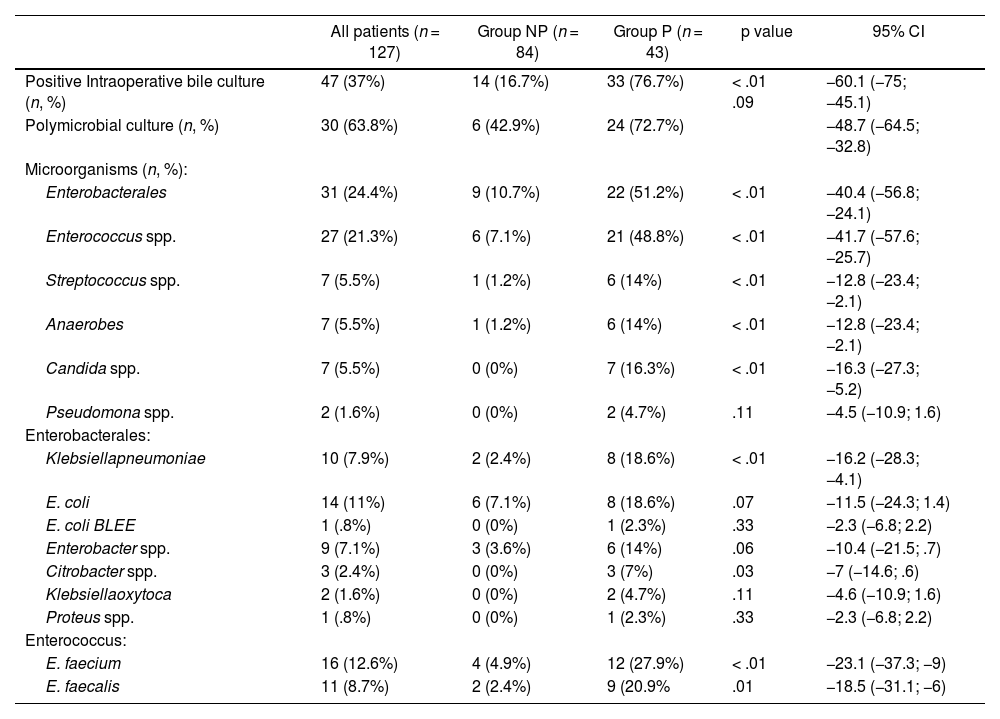

The NP group had positive IBC in 16.7% of patients and the P group in 76.7% (p < .01) with the majority of them being polymicrobial (72.7%) (Table 2).

Intraoperative microbiological results

| All patients (n = 127) | Group NP (n = 84) | Group P (n = 43) | p value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Intraoperative bile culture (n, %) | 47 (37%) | 14 (16.7%) | 33 (76.7%) | < .01 .09 | −60.1 (−75; −45.1) |

| Polymicrobial culture (n, %) | 30 (63.8%) | 6 (42.9%) | 24 (72.7%) | −48.7 (−64.5; −32.8) | |

| Microorganisms (n, %): | |||||

| Enterobacterales | 31 (24.4%) | 9 (10.7%) | 22 (51.2%) | < .01 | −40.4 (−56.8; −24.1) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 27 (21.3%) | 6 (7.1%) | 21 (48.8%) | < .01 | −41.7 (−57.6; −25.7) |

| Streptococcus spp. | 7 (5.5%) | 1 (1.2%) | 6 (14%) | < .01 | −12.8 (−23.4; −2.1) |

| Anaerobes | 7 (5.5%) | 1 (1.2%) | 6 (14%) | < .01 | −12.8 (−23.4; −2.1) |

| Candida spp. | 7 (5.5%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (16.3%) | < .01 | −16.3 (−27.3; −5.2) |

| Pseudomona spp. | 2 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4.7%) | .11 | −4.5 (−10.9; 1.6) |

| Enterobacterales: | |||||

| Klebsiellapneumoniae | 10 (7.9%) | 2 (2.4%) | 8 (18.6%) | < .01 | −16.2 (−28.3; −4.1) |

| E. coli | 14 (11%) | 6 (7.1%) | 8 (18.6%) | .07 | −11.5 (−24.3; 1.4) |

| E. coli BLEE | 1 (.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.3%) | .33 | −2.3 (−6.8; 2.2) |

| Enterobacter spp. | 9 (7.1%) | 3 (3.6%) | 6 (14%) | .06 | −10.4 (−21.5; .7) |

| Citrobacter spp. | 3 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (7%) | .03 | −7 (−14.6; .6) |

| Klebsiellaoxytoca | 2 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4.7%) | .11 | −4.6 (−10.9; 1.6) |

| Proteus spp. | 1 (.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.3%) | .33 | −2.3 (−6.8; 2.2) |

| Enterococcus: | |||||

| E. faecium | 16 (12.6%) | 4 (4.9%) | 12 (27.9%) | < .01 | −23.1 (−37.3; −9) |

| E. faecalis | 11 (8.7%) | 2 (2.4%) | 9 (20.9% | .01 | −18.5 (−31.1; −6) |

NP: No prosthesis; P: Prosthesis; p value: comparison between group NP and P; CI: Confidence interval; spp.: species. Chi square test for qualitative variables, Student's T for quantitative and Mann Whitney U for quantitative variables that do not follow normality.

The most frequent microorganisms in the IBC of the NP group were Enterobacterales and Enterococcus spp. In the P group there was a significant increase in these families of bacteria (p < .01), as well as a presence of Candida spp. in 16.3% of patients (p < .01) (Table 2).

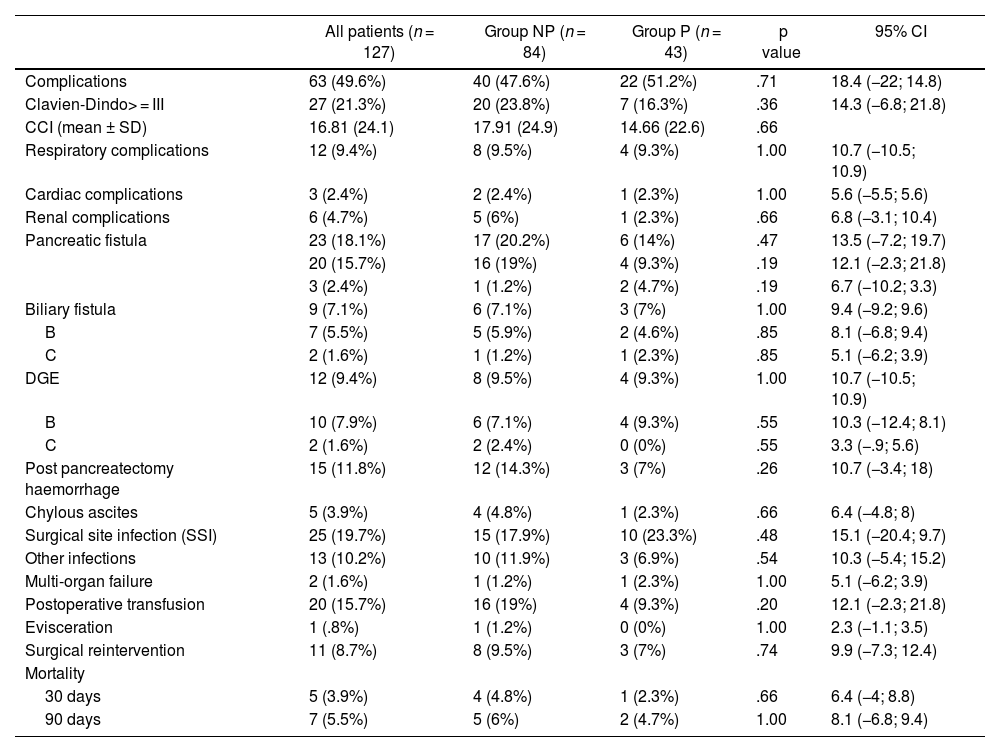

No significant differences were detected between Groups regarding medical complications, complications specific to pancreatic surgery or mortality at 30 or 90 days (Table 3).

Postoperative complications

| All patients (n = 127) | Group NP (n = 84) | Group P (n = 43) | p value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | 63 (49.6%) | 40 (47.6%) | 22 (51.2%) | .71 | 18.4 (−22; 14.8) |

| Clavien-Dindo> = III | 27 (21.3%) | 20 (23.8%) | 7 (16.3%) | .36 | 14.3 (−6.8; 21.8) |

| CCI (mean ± SD) | 16.81 (24.1) | 17.91 (24.9) | 14.66 (22.6) | .66 | |

| Respiratory complications | 12 (9.4%) | 8 (9.5%) | 4 (9.3%) | 1.00 | 10.7 (−10.5; 10.9) |

| Cardiac complications | 3 (2.4%) | 2 (2.4%) | 1 (2.3%) | 1.00 | 5.6 (−5.5; 5.6) |

| Renal complications | 6 (4.7%) | 5 (6%) | 1 (2.3%) | .66 | 6.8 (−3.1; 10.4) |

| Pancreatic fistula | 23 (18.1%) | 17 (20.2%) | 6 (14%) | .47 | 13.5 (−7.2; 19.7) |

| 20 (15.7%) | 16 (19%) | 4 (9.3%) | .19 | 12.1 (−2.3; 21.8) | |

| 3 (2.4%) | 1 (1.2%) | 2 (4.7%) | .19 | 6.7 (−10.2; 3.3) | |

| Biliary fistula | 9 (7.1%) | 6 (7.1%) | 3 (7%) | 1.00 | 9.4 (−9.2; 9.6) |

| B | 7 (5.5%) | 5 (5.9%) | 2 (4.6%) | .85 | 8.1 (−6.8; 9.4) |

| C | 2 (1.6%) | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (2.3%) | .85 | 5.1 (−6.2; 3.9) |

| DGE | 12 (9.4%) | 8 (9.5%) | 4 (9.3%) | 1.00 | 10.7 (−10.5; 10.9) |

| B | 10 (7.9%) | 6 (7.1%) | 4 (9.3%) | .55 | 10.3 (−12.4; 8.1) |

| C | 2 (1.6%) | 2 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) | .55 | 3.3 (−.9; 5.6) |

| Post pancreatectomy haemorrhage | 15 (11.8%) | 12 (14.3%) | 3 (7%) | .26 | 10.7 (−3.4; 18) |

| Chylous ascites | 5 (3.9%) | 4 (4.8%) | 1 (2.3%) | .66 | 6.4 (−4.8; 8) |

| Surgical site infection (SSI) | 25 (19.7%) | 15 (17.9%) | 10 (23.3%) | .48 | 15.1 (−20.4; 9.7) |

| Other infections | 13 (10.2%) | 10 (11.9%) | 3 (6.9%) | .54 | 10.3 (−5.4; 15.2) |

| Multi-organ failure | 2 (1.6%) | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (2.3%) | 1.00 | 5.1 (−6.2; 3.9) |

| Postoperative transfusion | 20 (15.7%) | 16 (19%) | 4 (9.3%) | .20 | 12.1 (−2.3; 21.8) |

| Evisceration | 1 (.8%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 | 2.3 (−1.1; 3.5) |

| Surgical reintervention | 11 (8.7%) | 8 (9.5%) | 3 (7%) | .74 | 9.9 (−7.3; 12.4) |

| Mortality | |||||

| 30 days | 5 (3.9%) | 4 (4.8%) | 1 (2.3%) | .66 | 6.4 (−4; 8.8) |

| 90 days | 7 (5.5%) | 5 (6%) | 2 (4.7%) | 1.00 | 8.1 (−6.8; 9.4) |

NP: No prosthesis; P: Prosthesis; p value: comparison between group NP and P; CI: Confidence interval; spp.: species. Chi square test for qualitative variables, Student's T for quantitative and Mann Whitney U for quantitative variables that do not follow normality.

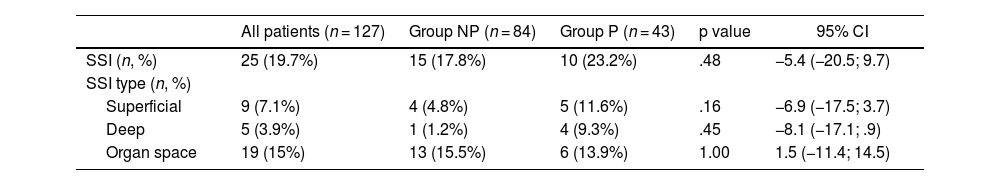

No differences were detected between Groups in the overall SSI rate (19.7%) or in its subtypes (Table 4).

Surgical Site Infection (SSI) in NP and P Groups

| All patients (n = 127) | Group NP (n = 84) | Group P (n = 43) | p value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSI (n, %) | 25 (19.7%) | 15 (17.8%) | 10 (23.2%) | .48 | −5.4 (−20.5; 9.7) |

| SSI type (n, %) | |||||

| Superficial | 9 (7.1%) | 4 (4.8%) | 5 (11.6%) | .16 | −6.9 (−17.5; 3.7) |

| Deep | 5 (3.9%) | 1 (1.2%) | 4 (9.3%) | .45 | −8.1 (−17.1; .9) |

| Organ space | 19 (15%) | 13 (15.5%) | 6 (13.9%) | 1.00 | 1.5 (−11.4; 14.5) |

NP: No prosthesis; P: Prosthesis; p value: comparison between group NP and P; CI: Confidence interval; spp.: species. Chi square test for qualitative variables, Student's T for quantitative and Mann Whitney U for quantitative variables that do not follow normality.

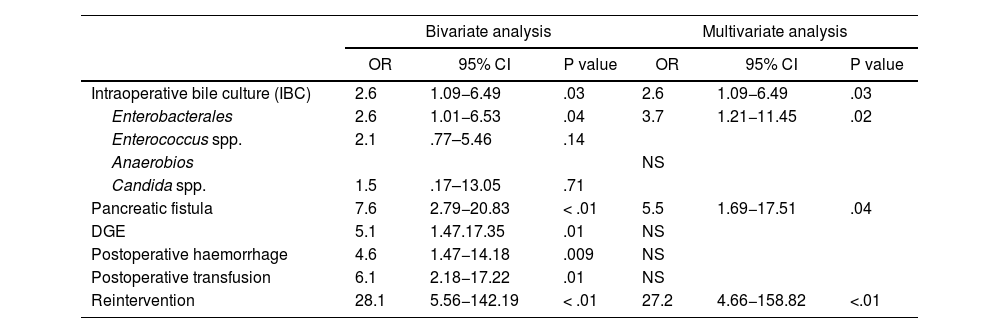

There were no significant differences in SSI regarding demographic, clinical, neoadjuvant treatment, or surgical variables. Bivariate analysis of SSI revealed significant differences in IBC for enterobacterales, presence of pancreatic fistula, delayed gastric emptying, postoperative haemorrhage, postoperative transfusion, and surgical reintervention (Table 5).

Surgical Site Infection (SSI). Bivariate and multivariate analysis

| Bivariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Intraoperative bile culture (IBC) | 2.6 | 1.09−6.49 | .03 | 2.6 | 1.09−6.49 | .03 |

| Enterobacterales | 2.6 | 1.01−6.53 | .04 | 3.7 | 1.21−11.45 | .02 |

| Enterococcus spp. | 2.1 | .77–5.46 | .14 | |||

| Anaerobios | NS | |||||

| Candida spp. | 1.5 | .17–13.05 | .71 | |||

| Pancreatic fistula | 7.6 | 2.79−20.83 | < .01 | 5.5 | 1.69−17.51 | .04 |

| DGE | 5.1 | 1.47.17.35 | .01 | NS | ||

| Postoperative haemorrhage | 4.6 | 1.47−14.18 | .009 | NS | ||

| Postoperative transfusion | 6.1 | 2.18−17.22 | .01 | NS | ||

| Reintervention | 28.1 | 5.56−142.19 | < .01 | 27.2 | 4.66−158.82 | <.01 |

OR: Odds Ratio; CI: confidence interval; spp.: species; DGE: Delayed Gastric Emptying. Logistic regression model.

While multivariate analysis revealed that significant risk factors for developing SSI were positive IBC for Enterobacterales, presence of pancreatic fistula and surgical reintervention (Table 5).

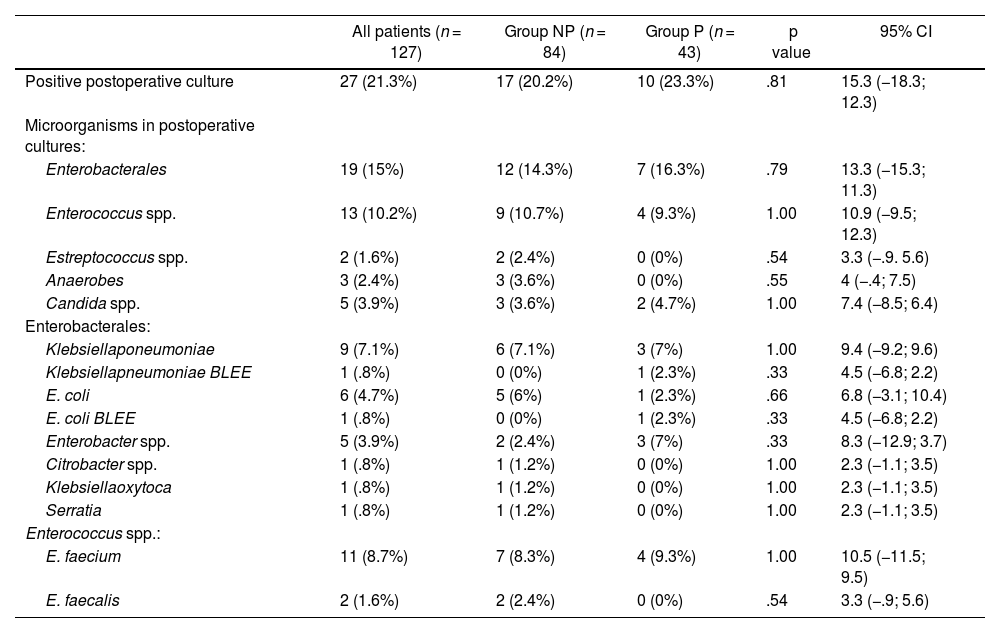

Postoperative SSI cultures (PC) are detailed in Table 6.

Postoperative culture results

| All patients (n = 127) | Group NP (n = 84) | Group P (n = 43) | p value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive postoperative culture | 27 (21.3%) | 17 (20.2%) | 10 (23.3%) | .81 | 15.3 (−18.3; 12.3) |

| Microorganisms in postoperative cultures: | |||||

| Enterobacterales | 19 (15%) | 12 (14.3%) | 7 (16.3%) | .79 | 13.3 (−15.3; 11.3) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 13 (10.2%) | 9 (10.7%) | 4 (9.3%) | 1.00 | 10.9 (−9.5; 12.3) |

| Estreptococcus spp. | 2 (1.6%) | 2 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) | .54 | 3.3 (−.9. 5.6) |

| Anaerobes | 3 (2.4%) | 3 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | .55 | 4 (−.4; 7.5) |

| Candida spp. | 5 (3.9%) | 3 (3.6%) | 2 (4.7%) | 1.00 | 7.4 (−8.5; 6.4) |

| Enterobacterales: | |||||

| Klebsiellaponeumoniae | 9 (7.1%) | 6 (7.1%) | 3 (7%) | 1.00 | 9.4 (−9.2; 9.6) |

| Klebsiellapneumoniae BLEE | 1 (.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.3%) | .33 | 4.5 (−6.8; 2.2) |

| E. coli | 6 (4.7%) | 5 (6%) | 1 (2.3%) | .66 | 6.8 (−3.1; 10.4) |

| E. coli BLEE | 1 (.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.3%) | .33 | 4.5 (−6.8; 2.2) |

| Enterobacter spp. | 5 (3.9%) | 2 (2.4%) | 3 (7%) | .33 | 8.3 (−12.9; 3.7) |

| Citrobacter spp. | 1 (.8%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 | 2.3 (−1.1; 3.5) |

| Klebsiellaoxytoca | 1 (.8%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 | 2.3 (−1.1; 3.5) |

| Serratia | 1 (.8%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 | 2.3 (−1.1; 3.5) |

| Enterococcus spp.: | |||||

| E. faecium | 11 (8.7%) | 7 (8.3%) | 4 (9.3%) | 1.00 | 10.5 (−11.5; 9.5) |

| E. faecalis | 2 (1.6%) | 2 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) | .54 | 3.3 (−.9; 5.6) |

NP: No prosthesis; P: Prosthesis; p value: comparison between group NP and P; CI: Confidence interval; Chi square test for qualitative variables.

When we analysed the microorganisms that caused SSI in Group P, comparing the intraoperative and postoperative cultures, we noted that many microorganisms present in the intraoperative culture disappeared.

The microorganisms that persisted and caused the infection did so due to intrinsic resistance to Piperacillin-Tazobactam or by developing ESBL resistance: Extended Spectrum Beta-lactamase.

The antibiotic treatment was modified in 17.3% of the patients according to the PC obtained from SSI without detecting differences between Groups: 15 (17.8%) vs. 7 (16.3%).

DiscussionPD remains a complex surgery with high morbidity and up to 30% of complications are infectious.21 The need for preoperative biliary drainage is considered a risk factor for the appearance of SSI.22 Donald et al.9 detected the presence of Enterococcus spp. and Enterobacter in wound infections and reduced SSI by 80% by applying broad-spectrum prophylaxis with piperacillin-tazobactam. Based on this fact, we applied the same treatment in our hospital only to patients with biliary prostheses, considered at risk, since they had twice as many organ-space SSIs compared to non-carriers (28% vs 14%, unpublished data).

Although in our series there is a significant increase in Enterobacterales, Enterococcus spp. and Candida spp. in bile of patients in Group P, this did not entail an increase in the rate of SSI compared to Group NP or in the different types (superficial, deep or organ-space) when applying a perioperative treatment directed to the flora expected in this Group with piperacillin-tazobactam.

Recent studies23,24 demonstrate the reduction of SSI and pancreatic fistula using piperacillin-tazobactam prophylaxis in postoperative PD, although patients with or without biliary prosthesis are mixed in both groups.

It is known that biliary obstruction can lead to bacterial overgrowth.25 Biliary manipulation increases colonisation up to 70%–100%26 and is polymicrobial27 in most cases. According to Mussel's meta-analysis,28 the P group shows more bacteriobilia than the NP group in intraoperative cultures, the majority being polymicrobial (72.7% vs. 42.9%, p = .09).

Since biliary contamination favours SSI after PD, and it is essential to perform intraoperative cultures to identify bacterobilia29 and resistance rate in each health area. In line with other authors,30–32 our study revealed that the most frequent microorganisms were Enterobacterales and Enterococcus spp.

There is a progressive increase in Enterococcus in the flora of patients33 and, although there are authors who argue that they are part of the normal biliary flora, the pathogenicity of E. faecalis34 must be considered.

We detected Candida spp. in 16.3% of cases only in the P group (p < .01), coinciding with what was published by Scheufele,7 although its pathogenicity is not well defined in this context and therefore its management remains controversial. According to the results obtained, a positive intraoperative culture for Candida spp. does not represent an independent risk factor for the development of SSI. Thus, systematic antifungal prophylaxis is not considered necessary.

The use of intraoperative Gram staining35 is a good strategy used by some groups to control SSI after knowing the flora on the same day of the intervention, although we did not use it since it may require a high variability of antibiotic combinations.

Among this study’s limitations we would highlight the fact that it was a retrospective study and after seeing the results obtained, the same scheme could be proposed with a shorter treatment duration. As strengths, we highlight the homogeneity in the surgical treatment and in the analysis of microbiological results, since it was developed in a single centre.

The perioperative treatment scheme with piperacillin-tazobactam only in group P, unlike other studies, can prevent the development of resistance in group NP, although the low presence of resistant bacteria in group P (2.3% of ESBL E.Coli) is notable, probably due to the low preoperative antibiotic pressure.

We therefore conclude that: the bacteriobilia is different in patients with preoperative biliary drainage compared to non-drained patients, finding in group P a significant increase in Enterobacterales, Enterococcus spp. and Candida spp.

No differences were observed in the rate of SSI after PD applying perioperative antibiotic treatment directed to the biliary flora of each group. Intraoperative biliary culture positive for Enterobacterales turned out to be an independent risk factor for developing SSI.

We therefore propose the need to change conventional surgical prophylaxis to perioperative antibiotic treatment based on the expected bacterobilia and the resistance profile of each healthcare area in patients with preoperative biliary prosthesis.

FundingThis study did not receive any specific funding from any public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit entities.

Ethical approvalThis study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of our institution (Date: 24/03/2021, No O/21-043).

Conflict of interestsNone.

We would like to thank Dr. Esther Calbo, head of the Infectious Diseases Service, and also Dr. Eva Cuchí, assistant of the Microbiology Service, for their participation in the study.