The major goal of surgical treatment in morbid obesity is to decrease morbidity and mortality associated with excess weight. In this sense, the main factors of death are cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome. The objective of this study is to evaluate the effects of gastric bypass on cardiovascular risk estimation in patients after bariatric surgery.

Materials and methodsWe retrospectively evaluated pre- and postoperative cardiovascular risk estimation of 402 morbidly obese patients who underwent laparoscopic gastric bypass.

The major variable studied is the cardiovascular risk estimation that is calculated preoperatively and after 12 months. Cardiovascular risk estimation analysis has been performed with the REGICOR Equation. REGICOR formulation allows calculating a 10-year risk of cardiovascular events adapted to the Spanish population and is expressed in percentages.

ResultsWe reported an overall 4.1±3.0 mean basal REGICOR score. One year after the operation, cardiovascular risk estimation significantly decreased to 2.2±1.6 (P<.001). In patients with metabolic syndrome according to ATP-III criteria, basal REGICOR score was 4.8±3.1 whereas in no metabolic syndrome patients 2.2±1.8. Evaluation 12 months after surgery determined a significant reduction in both groups (metabolic syndrome and non metabolic syndrome) with a mean REGICOR score of 2.3±1.6 and 1.6±1.0 respectively.

ConclusionThe results of our study demonstrate favorable effects of gastric bypass on the cardiovascular risk factors included in the REGICOR equation.

El objetivo final del tratamiento quirúrgico en la obesidad mórbida es el descenso de la morbimortalidad asociada al exceso de peso. En este sentido debemos centrarnos en la enfermedad cardiovascular y el síndrome metabólico, que son las causas principales de mortalidad. El objetivo del estudio es valorar el efecto del bypass gástrico sobre el riesgo cardiovascular estimado en los pacientes sometidos a cirugía bariátrica.

Material y métodosEstudio clínico retrospectivo y observacional desarrollado en 402 pacientes sometidos a bypass gástrico por laparoscopia. La variable principal a estudio es el riesgo cardiovascular estimado, que se mide en el preoperatorio y a los 12 meses. Para el cálculo del riesgo estimado se utiliza la ecuación REGICOR, que se expresa en forma de porcentaje y calcula el riesgo a 10 años de presentar enfermedad cardiovascular.

ResultadosEn situación basal observamos como media un índice REGICOR de 4,1±3,0. A los 12 meses de la intervención la estimación del riesgo cardiovascular disminuyó significativamente a 2,2±1,6 (p<0,001). En los sujetos con el diagnóstico de síndrome metabólico según definición del ATP-III, el REGICOR basal fue de 4,8±3,1, mientras que en aquellos sin síndrome fue de 2,2±1,8. A los 12 meses observamos una reducción significativa en ambos grupos (síndrome metabólico y no síndrome) con un REGICOR medio de 2,3±1,6 y 1,6±1,0 respectivamente.

ConclusiónLos resultados observados en nuestro estudio demuestran los efectos favorables del bypass gástrico sobre los factores de riesgo cardiovascular incluidos en la ecuación REGICOR.

The major goal of surgical treatment in morbid obesity (MO) is to decrease morbimortality associated with excess weight. Since cardiovascular disease is the main cause of death in morbidly obese patients, attention must focus here.1 The presence of metabolic syndrome (MS) has also been noted to increase the risk of diabetes mellitus development, up to twice the risk of cardiovascular disease and one and a half times the risk of mortality due to other causes.2

In 2001 the National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP-III) published its definition of MS.3 Presentation of MS, according to the ATP-III only requires three out of the five following factors: increased waist circumference (WC), hypertryglyceridaemia, decreased HDL (C-HDL) cholesterol level, blood pressure of >130/85mm impaired fasting Hg and glucose levels of >110mg/dl. More recent ARP-III recommendations advise that particular attention should be made to MS as a cardiovascular risk (CVR) marker and that strategies be implemented for weight reduction.4

Various studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of surgery on diseases associated with MO.5 Laparoscopic gastric bypass (LGB) is the most commonly performed procedure since it produces weight loss maintained over time, improves patients’ quality of life and increases life expectancy.6 Improvement in life expectancy is mainly due to resolving or improving MS components (hyperglycaemia, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and abdominal obesity or impaired WC) which are the bases of cardiovascular disease development. An individual's CVR may be quantified from equations which combine different parameters related to cardiovascular disease and risk estimation. The “Registre Gironí del Cor” (REGICOR)7 equation is noted for its formula which enables a ten-year risk calculation of any coronary event, adapted to risk factor prevalence characteristics and the incidence of coronary events in the Spanish population.

Our working hypothesis is that LGB is a highly effective, safe treatment for MS control. It is also associated with improved estimated CVR in the morbidly obese. The aim of our study was to evaluate the effect of LGB on estimated CVR using the REGICOR equation in patients undergoing surgery for obesity.

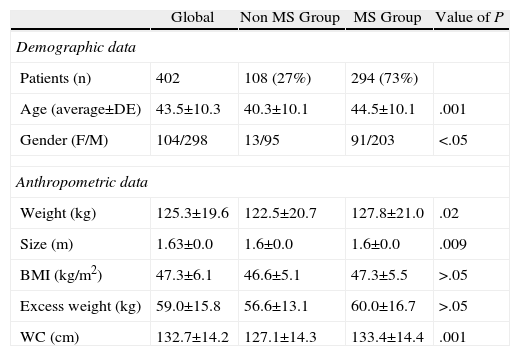

Materials and MethodsWe carried out a retrospective, single centre study which analysed a consecutive series of 402 LGB patients from January 2007 until December 2008. Demographic characteristics of the series are described in Table 1. All patients met the criteria established by the 1991 National Institutes of Health consensus conference on the surgical treatment of obesity and had signed informed consent forms.8

Characteristics of the series.

| Global | Non MS Group | MS Group | Value of P | |

| Demographic data | ||||

| Patients (n) | 402 | 108 (27%) | 294 (73%) | |

| Age (average±DE) | 43.5±10.3 | 40.3±10.1 | 44.5±10.1 | .001 |

| Gender (F/M) | 104/298 | 13/95 | 91/203 | <.05 |

| Anthropometric data | ||||

| Weight (kg) | 125.3±19.6 | 122.5±20.7 | 127.8±21.0 | .02 |

| Size (m) | 1.63±0.0 | 1.6±0.0 | 1.6±0.0 | .009 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 47.3±6.1 | 46.6±5.1 | 47.3±5.5 | >.05 |

| Excess weight (kg) | 59.0±15.8 | 56.6±13.1 | 60.0±16.7 | >.05 |

| WC (cm) | 132.7±14.2 | 127.1±14.3 | 133.4±14.4 | .001 |

WC: waist circumference; BMI: body mass index; F: female; M: male.

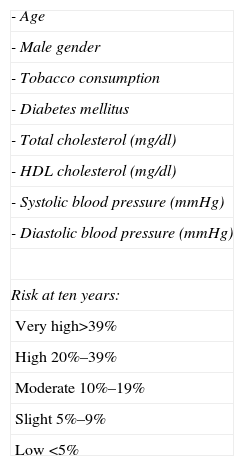

Patients were carefully assessed by a multidisciplinary team from our hospital's Functional Obesity Unit prior to surgery. Data were collected prospectively for retrospective analysis of MS prevalence and CVR alteration during follow-up, from periodic check-ups at four, eight and twelve months after surgery. The presence of MS was determined in each patient according to ATP-III criteria and the MS score or component number present (0–5). We used the REGICOR equation to calculate the estimated CVR, which included age, sex, tobacco use and presence of diabetes mellitus. It also counted total cholesterol levels, C-HDL, systolic and diastolic blood pressure (Table 2). The REGICOR result is expressed as a percentage and it indicates the risk of developing a coronary event in the next ten years.7

Risk Factors Included in REGICOR and Risk Classification.

| - Age |

| - Male gender |

| - Tobacco consumption |

| - Diabetes mellitus |

| - Total cholesterol (mg/dl) |

| - HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) |

| - Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

| - Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

| Risk at ten years: |

| Very high>39% |

| High 20%–39% |

| Moderate 10%–19% |

| Slight 5%–9% |

| Low <5% |

The statistical programme SPSS for Windows 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago) was used for analysis. Baseline patient variables were subject to descriptive analysis. We used frequencies and percentages to describe the categorical variables and means with standard or median deviations to describe the continuous variables. We used Fisher's exact test for comparison of categorical variables and the Students t-test for continuous variables. The statistical significance level for all analysis was fixed at 5%, value α=0.05. Calculation of sample size was obtained for α=0.05 assuming a 5 to 2.5% reduction in CVR in 400 patients.

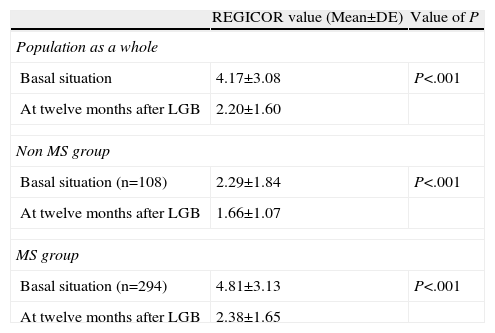

ResultsWe studied the estimated CVR of our population in order to determine the effect of LGB on CVR. Prior to surgical intervention the mean REGICOR score observed for the whole series was 4.17±3.08. Presurgical risk in patients was therefore low according to the REGICOR (<5%) stratification. The simple presence of MS does therefore not translate as high CVR. We can also state that twelve months after surgery the estimated CVR significantly lowered to 2.20±1.6 P<.001 (Table 3).

REGICOR Evolution After LGB.

| REGICOR value (Mean±DE) | Value of P | |

| Population as a whole | ||

| Basal situation | 4.17±3.08 | P<.001 |

| At twelve months after LGB | 2.20±1.60 | |

| Non MS group | ||

| Basal situation (n=108) | 2.29±1.84 | P<.001 |

| At twelve months after LGB | 1.66±1.07 | |

| MS group | ||

| Basal situation (n=294) | 4.81±3.13 | P<.001 |

| At twelve months after LGB | 2.38±1.65 | |

LGB: laparoscopic gastric bypass; MS: metabolic syndrome.

REGICOR improvement occurred in both patients who had and did not have MS prior to LGB. In patients without MS prior to LGB (n=108) REGICOR was 2.29±1.84, whilst in those patients with MS (n=294) it was 4.81±3.13, P<.001. Twelve months after surgery the REGICOR equation showed a significant decrease in both groups (P<.001). For patients without MS the REGICOR mean was 1.66±1.07 and for those with MS it was 2.38±1.65 (Table 3).

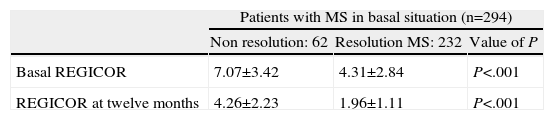

We also separately analysed the estimated CVR evolution in patients who presented MS before surgery. Results were expressed (mean±standard deviation) according to subsequent resolution or non-resolution of MS (Table 4). Data show a significant reduction in estimated CVR, both for patients whose MS was resolved after twelve months and for those for whom it was not. Despite the improvement, surgery in MS patients did not have the same REGICOR score as the group who did not present with MS before surgery; 1.96±1.11 vs 1.66±1.07 (P<.05). A patient, whose MS was not resolved after surgery, had the highest REGICOR score prior to surgery too. Estimated CVR did improve after LGB, but remained high after twelve months, with the REGICOR score at 4.26±2.23 (Table 4).

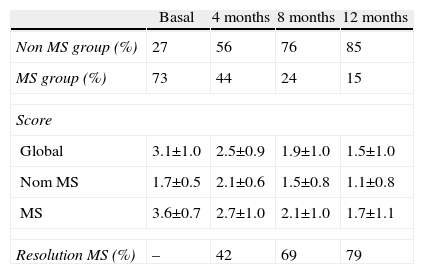

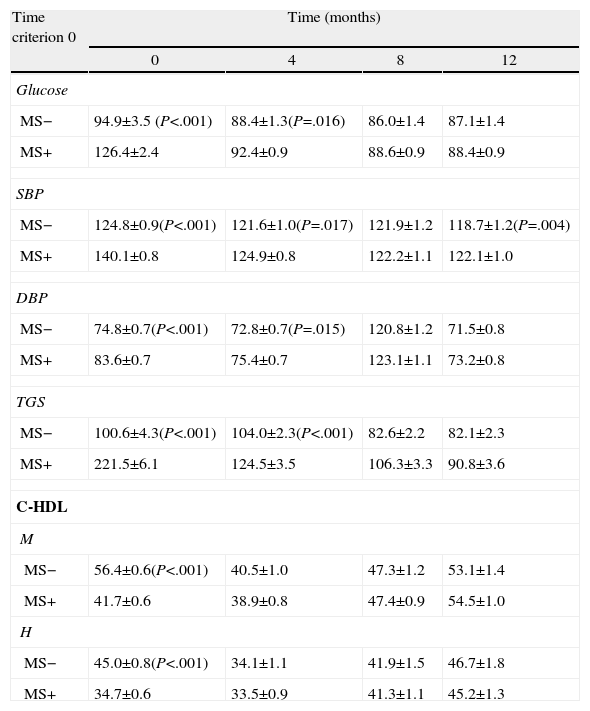

We simultaneously examined the development of MS prevalence after surgery (Table 5). Data obtained during postoperative follow-up showed the marked beneficial effect of LGB on MS and its components. An MS resolution of 79% and its 15% prevalence twelve months after surgery were observed (MS prevalence prior to surgery was 73%). Table 6 shows how each MS component developed after surgery, depending on whether MS had been present or not in the baseline situation.

Evolution of the Prevalence of MS and Its Score After LGB.

| Basal | 4 months | 8 months | 12 months | |

| Non MS group (%) | 27 | 56 | 76 | 85 |

| MS group (%) | 73 | 44 | 24 | 15 |

| Score | ||||

| Global | 3.1±1.0 | 2.5±0.9 | 1.9±1.0 | 1.5±1.0 |

| Nom MS | 1.7±0.5 | 2.1±0.6 | 1.5±0.8 | 1.1±0.8 |

| MS | 3.6±0.7 | 2.7±1.0 | 2.1±1.0 | 1.7±1.1 |

| Resolution MS (%) | – | 42 | 69 | 79 |

Evolution of Main MS Components After LGB.

| Time criterion 0 | Time (months) | |||

| 0 | 4 | 8 | 12 | |

| Glucose | ||||

| MS− | 94.9±3.5 (P<.001) | 88.4±1.3(P=.016) | 86.0±1.4 | 87.1±1.4 |

| MS+ | 126.4±2.4 | 92.4±0.9 | 88.6±0.9 | 88.4±0.9 |

| SBP | ||||

| MS− | 124.8±0.9(P<.001) | 121.6±1.0(P=.017) | 121.9±1.2 | 118.7±1.2(P=.004) |

| MS+ | 140.1±0.8 | 124.9±0.8 | 122.2±1.1 | 122.1±1.0 |

| DBP | ||||

| MS− | 74.8±0.7(P<.001) | 72.8±0.7(P=.015) | 120.8±1.2 | 71.5±0.8 |

| MS+ | 83.6±0.7 | 75.4±0.7 | 123.1±1.1 | 73.2±0.8 |

| TGS | ||||

| MS− | 100.6±4.3(P<.001) | 104.0±2.3(P<.001) | 82.6±2.2 | 82.1±2.3 |

| MS+ | 221.5±6.1 | 124.5±3.5 | 106.3±3.3 | 90.8±3.6 |

| C-HDL | ||||

| M | ||||

| MS− | 56.4±0.6(P<.001) | 40.5±1.0 | 47.3±1.2 | 53.1±1.4 |

| MS+ | 41.7±0.6 | 38.9±0.8 | 47.4±0.9 | 54.5±1.0 |

| H | ||||

| MS− | 45.0±0.8(P<.001) | 34.1±1.1 | 41.9±1.5 | 46.7±1.8 |

| MS+ | 34.7±0.6 | 33.5±0.9 | 41.3±1.1 | 45.2±1.3 |

C-HDL: cholesterol; HDL H: male; M: female; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure; MS−: absence of metabolic syndrome (MS); MS+: presence of MS; TGS: triglycerides.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the impact of LGB on cardiovascular disease in severely obese patients. We focused on estimated CVR evaluation, since follow-up time and patient characteristics (predominantly female and 4th decade average age) prevented us from addressing this issue based on the appearance of cardiovascular events.

There are several multivariate equations for calculating the probability of a cardiovascular event in a patient. The most well known and most extensively used was developed from follow-up of the Framingham population (MN, USA).9 This equation summarises the majority of main CVR factors and is a practical tool for CVR estimation at ten years in obese patients with or without MS. The Framingham equation, however, has several limitations when applied to our population as it overestimates CVR by more than two and a half. Furthermore, the Framingham assumption of diabetes as equivalent to coronary risk does not appear to apply in our environment. For this reason the Framingham equation is not recommended in Spain and REGICOR is recommended as an alternative.10 The latter is the result of calibration using a contrasted methodology of the original Framingham equation, and has proven that its CVR estimation at ten years is more precise for the Spanish population, compared with other available equations.7

Before surgery the mean CVR in Spain according to the REGICOR estimation was 4.17%±3.0%. This mean score positions the Spanish population as low CVR (CVR at ten years<5%), despite the degree of obesity (factor not included in the calculation). MS patients presented not only a higher CVR (4.17%±3.0%) estimate, but also globally low risk range. Similar results were reported by Ocon et al., who observed an estimated 4.5% CVR in its sample of 46 LGB patients.11

The low CVR observed in our study and in that of Ocon et al. do not correlate with other publications. Mackey et al. determined that the CVR calculated at 10 years in patients who were candidates for bariatric surgery was usually high in 36% of cases.12 The differences between the different series could be due to the type of score used to calculate the estimated CVR, which in the majority of studies used the Framingham algorithm.

The principal therapy in MS patients should be based on weight loss. Phelan et al.13 demonstrated that a moderate weight loss (8.0±8.7kg) could contribute to a drop in MS prevalence. For their part, Camhi et al.14 suggested the combination of diet and exercise as the most effective therapy. Finally, in an observational study Eilat-Adar demonstrated that a six-month dietary treatment with weight loss of at least 4.5kg led to a reduction in relative risk of coronary disease of 0.57 (95% confidence interval: 0.39–0.84) after 4 years of follow-up.15 If this is the potential of moderate weight loss, what would a more effective intervention on weight loss such as LGB achieve? Several authors including Batsis, Vogel, Kligman and Torquati assessed the effect of bariatric surgery on estimated CVR using the Framingham algorithm. CVR estimation prior to surgery in these studies is higher than that of our series. This may be due to the use of the Framingham equation. Batsis et al., in a systematic review with 197 gastric bypass patients observed that surgical treatment reduced CVR by 7.0% in the initial period to 3.5% on completing the study.16 In the Vogel et al. study (n=109) the estimated presurgical CVR was 12% in men and 5% in women, falling to 6% and 3%, respectively, at 17-month follow-up.17 In this study gastric bypass reduced the CVR to lower levels than those estimated for the general population of the same age and sex. Similarly, Kligman et al. showed in a retrospective series of 101 patients in which LGB was associated with a 52% reduction (from 6.7 to 3.2%) in estimated CVR at ten years.18 Finally, in an extensive patient series (n=500), Torquati et al. showed an estimated CVR reduction using the Framingham equation of 5.7%–2.7% at 12 months after LGB.19

Our series’ results are globally comparable with the ones mentioned above. Twelve months after surgery our patients presented a significant drop in estimated CVT, from 2.2%±1.6%. Our study also revealed additional interesting information. Unlike previous studies, we divided the patients according to MS presence or non-presence before surgery, and also according to its resolution or non-resolution after twelve months postsurgical follow-up. Our data showed that in patients without MS the drop was 28%, whilst those with MS presented a relative reduction in estimated CVR of 51%. Finally, our data showed that patients with MS in whom the syndrome did not resolve in the end were those with a higher estimated CVR before surgery (approximately 7%), and who responded the least well to treatment regarding this risk reduction. Older age (a negative determining feature in MS evolution after LGB) is a determining factor of greater CVR before and after surgery. We do however interpret this as an argument to emphasize the ideal use of surgery in early stages in obese and MS patients (younger patients with fewer metabolic complications). In another long patient series (n=650) with adjustable gastric bands a significant improvement of CVR factors and global risk was observed at fifteen months follow-up, despite low weight loss (mean 22.7±20kg).20

As mentioned at the start of the discussion we aimed to evaluate the impact of LGB on estimated CVR at ten years. Are there other more specific ideas about the effect of surgery on cardiovascular disease in MO patients? We first considered the impact of bariatric surgery on the carotid intima-media complex thickness. The thickness of this part of the arterial wall is a good indicator of cardiovascular disease in early stages and increases in patients with obesity (particularly abdominal) in comparison with the control group. We only found two mentions in the literature which followed this debate. Both studies presented methodological limitations, but in two cases there was a significant reduction in carotid intima-media thickness. In the work by Habib et al.21 LGB was associated with a reduction in carotid intima-media thickness of 0.84–0.50mm after 24 months (P<.001). The Sarmento22 study, however, showed that this change occurred earlier (at six months after surgery) and that it correlated with changes in MS components (specifically triglycerides and systolic blood pressure).

Few studies have examined the relationship between bariatric surgery and the appearance of cardiovascular events. In 2004 Christou et al.23 reported on a two-year observational study comparing a series of 1035 patients who had undergone gastric bypass and 5746 control individuals (with similar gender and age distribution). They showed that weight loss through surgery was capable of significantly reducing the risk of developing cardiovascular events. More recent studies point in the same direction.24 We highlight work by the SOS study group Sjöstrom et al., for its long-term follow-up showing a reduction in mortality from cardiovascular causes and in the incidence of cardiovascular events in patients who had undergone surgery (n=2010) compared with patients who had received conventional treatment (n=2037), P=.002.25

We accept this study has its limitations. The short postoperative follow-up of the sample (twelve months) and comparison between series which used different equations for CVR calculation would be some of them. Bias could also exist when statistically comparing the score of the group with MS and that without MS, since these are not strictly homogenous groups in several variables such as age and gender.

In conclusion, although there are currently no data from prospective random clinical trials, all data suggest a beneficial effect of LGB on the incidence and mortality by cardiovascular disease in MO patients. The data in this article support this hypothesis of the beneficial effect of LGB on the main modifiable CVR factors included in the REGICOR equation.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Corcelles R, Vidal J, Delgado S, Ibarzabal A, Bravo R, Momblan D, et al. Efectos del bypass gástrico sobre el riesgo cardiovascular estimado. Cir Esp. 2014;92:16–22.

Presented at the 20th International Congress of the European Association of Endoscopic Surgery, Brussels, 20–23 June 2012, Belgium.