La reparación endovascular torácica (TEVAR) se ha constituido como una alternativa válida para la reparación de los aneurismas torácicos, al ser menos agresiva. Una reciente revisión sistemática y metaanálisis de estudios comparativos confirma que TEVAR, cuando se compara con la cirugía abierta, puede reducir la muerte precoz, la paraplejía, insuficiencia renal, transfusiones, reoperación por hemorragia, complicaciones cardíacas, neumonía y estancia hospitalaria. Esta revisión se referirá a algunas de las complicaciones del procedimiento. Éstas incluyen: mortalidad, accidente cerebrovascular, isquemia medular, disección retrógrada, disfunción del dispositivo, complicaciones del acceso, endofuga y migración.

Thoracic endovascular repair (TEVAR) has emerged as a valid alternative for thoracic aortic aneurysm repair as it is less invasive. Recent systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies found that TEVAR, compared to open surgery, may reduce early death, paraplegia, renal insufficiency, transfusions, reoperation for bleeding, cardiac complications, pneumonia, and length of stay. This review will address some of the reported complications after this procedure. These include: mortality, stroke, spinal cord ischemia, retrograde dissection, device malfunction, access complications, endoleak, and migration.

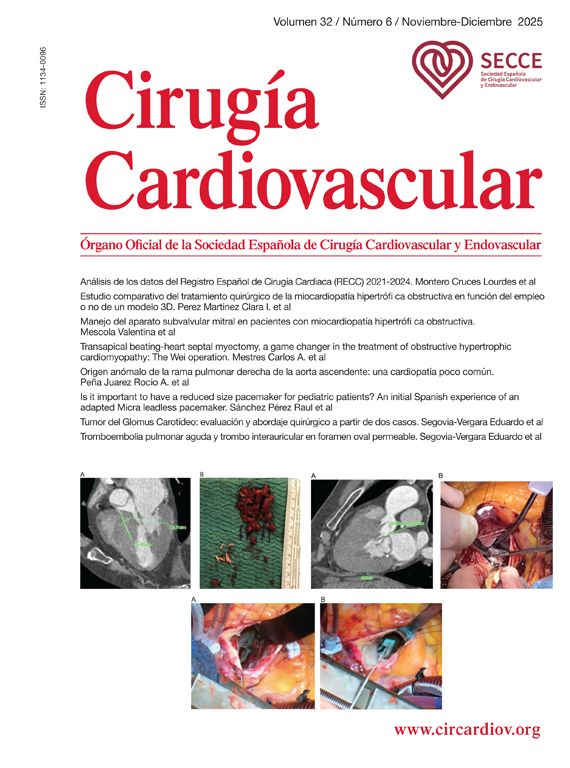

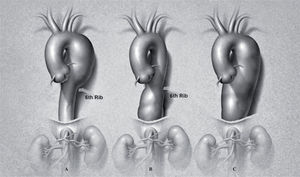

Aortic aneurysms are the 13th leading cause of death in the United States. The prevalence of aortic aneurysms appears to be increasing secondary to heightened awareness, improvements in imaging, and an aging population1. The incidence of thoracic aortic aneurysms (TAA) is 5.9 new cases/100,000 person-years2. The mean age at diagnosis ranges between 59-69 years, with a male-to-female ratio of 2:1-4:13. Natural history studies suggest that, after diagnosis, 74% of thoracic aneurysms rupture at a median interval of 2 years (range 1 months to 16 years)2. Patients with thoracic aneurysms often have significant comorbidities including hypertension, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and congestive heart failure3. Descending thoracic aortic aneurysms are classified into three types (Fig. 1): extent A (left subclavian artery to 6th rib), extent B (6th rib to diaphragm) and extent C (left subclavian artery to diaphragm)4.

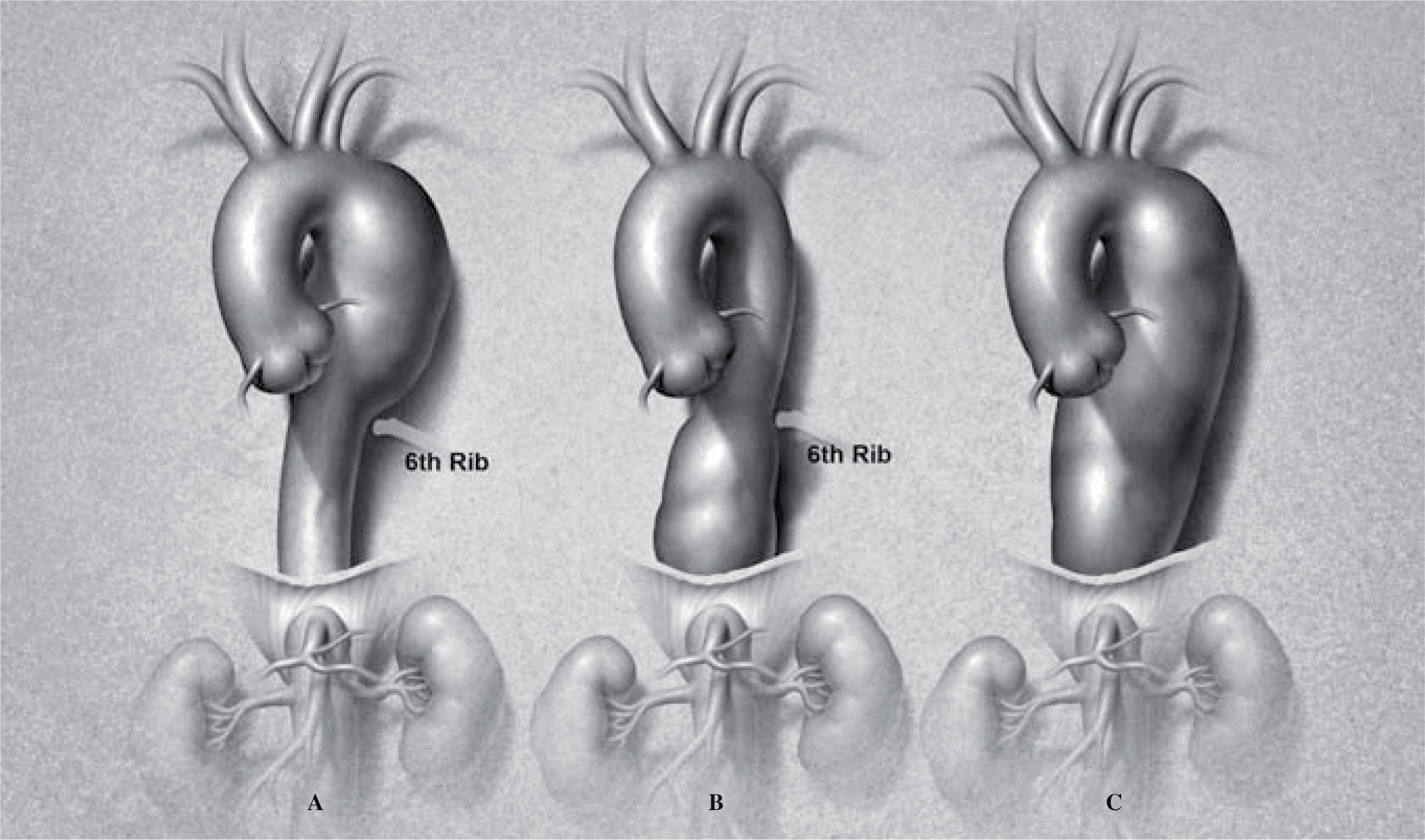

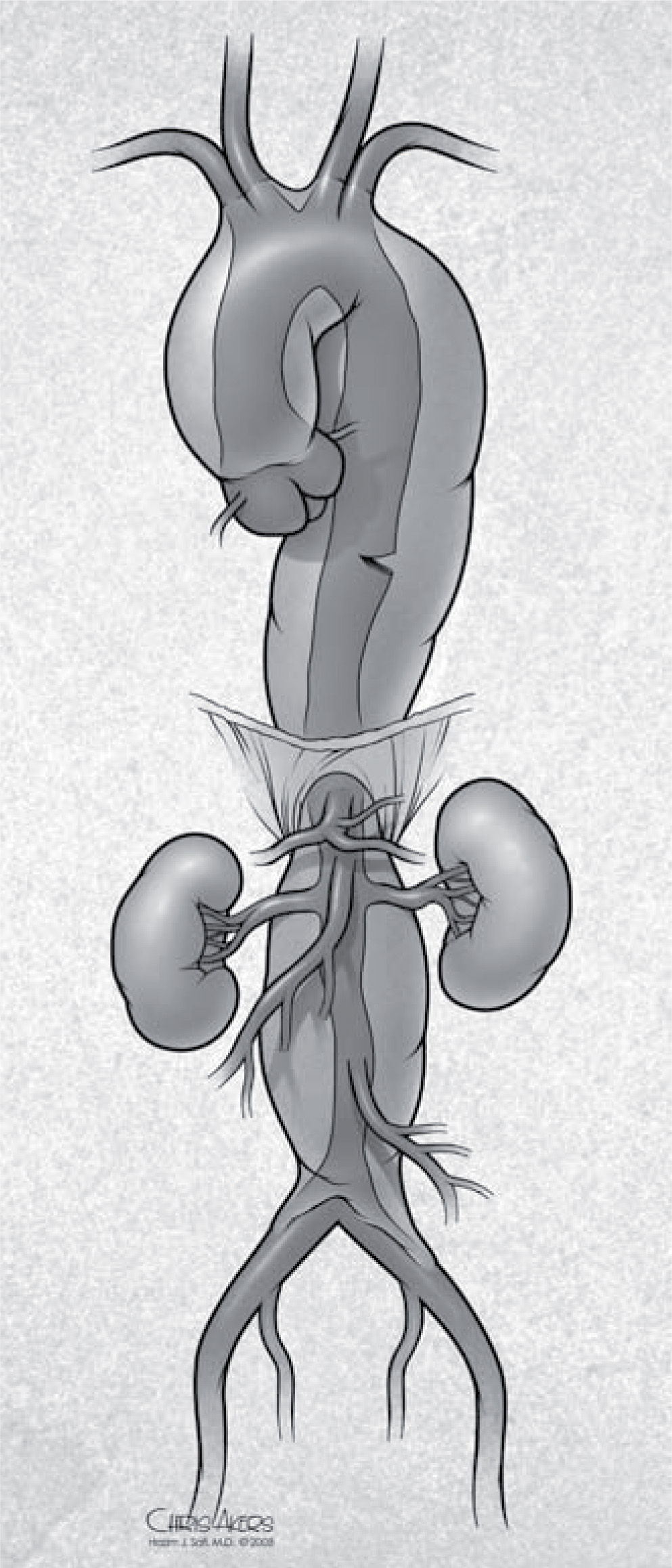

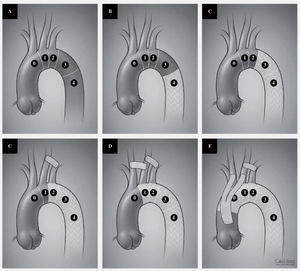

Since the 1950’s, open surgical repair using a prosthetic graft has been the main treatment for patients with TAA. Open surgery involves thoracotomy, aortic cross-clamping, and major blood loss with potentially significant impacts on the heart, lung, kidneys, brain and the spinal cord. As a result, this approach is associated with significant morbidity and mortality with variable results in different centers5–8. Thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR), first developed in 1990’s, has been adopted as a minimally invasive alternative for treatment of TAA9. The first thoracic device was approved in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 200510. Two additional devices were later approved11,12. In all three pivotal trials, endovascular repair compared favorably to the traditional open repair for management of degenerative aneurysms. Published experience with TEVAR is rapidly accumulating. More complex aneurysms extending to the aortic arch vessels are now commonly treated with endovascular repair (Fig. 2). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies found that TEVAR, compared to open surgery, may reduce early death, paraplegia, renal insufficiency, transfusions, reoperation for bleeding, cardiac complications, pneumonia, and length of stay13. The aim of this review is to address some of the reported complications after this procedure. These include: mortality, stroke, spinal cord ischemia, retrograde dissection, device malfunction, access complications, endoleak, and migration.

A: distribution of landing zones for TEVAR. Zone 0: repair involving the innominate artery. Zone 1: involving the left carotid artery. Zone 2: involving the left subclavian artery. Zone 3: involving the proximal third of the descending thoracic aorta. Zone 4: involving the distal two thirds of the descending thoraci aorta. B and C: placement of a device in zone 3 or 4 without any revascularization. D: coverage of the left subclavian artery with a left carotid subclavian bypass. E: coverage of the left carotid and subclavian arteries with a carotid-carotid and carotid subclavian bypass. F: complete arch coverage with ascending aorta to innominate and left carotid bypass as well as a left carotid subclavian bypass.

According to a systematic review and meta-analysis which included 42 non-randomized studies (38 comparative, 4 registries) involving 5,888 patients, the cumulative 30-day risk of mortality was 5.8% for TEVAR compared to 13.9% for open repair (p < 0.00001)13. The cumulative all-cause mortality at 1, 2, and 3 years did not differ significantly between the two groups. Although TEVAR patients were significantly older, other baseline characteristics including coronary artery disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension and renal insufficiency were not significantly different between the two groups.

StrokeAlthough TEVAR has a pattern of complications that are unique to endovascular procedures, perioperative stroke has a similar rate in both open and endovascular interventions (6.2 vs. 5%)13. Stroke is among the most feared and devastating complications of endovascular and open repairs of the thoracic aorta. Perioperative stroke after TEVAR may be related to systemic factors (hypotension, hypertension, anticoagulation), intracranial causes (hemorrhage, edema, CSF drainage) or emboli (air, atheroma, thrombus)14.

Embolization may be related to the use and advancement of wires, catheters, and devices into a diseased atheromatous aortic arch, with dislodgement of atherosclerotic plaque to the brain. As a result, patients with a significant atherosclerotic burden and those with aneurysms close to the aortic arch are inherently at higher risk. In a 2007 review of 171 patients undergoing TEVAR, Gutsche, et al. reported a 5.8% incidence of stroke15. Severe atheromatous aortic disease (> 5mm protrusion into aortic lumen), found in 7 of 8 perioperative stroke patients, was strongly associated with stroke (p=0.0016). Combining a history of prior stroke with extent A coverage carried a 60% stroke incidence, while extent C resulted in a 15% incidence. After reviewing these data, 3 risk factors for perioperative stroke were identified: a) a history of preoperative stroke; b) CT grade IV atheroma (> 5mm) in the aortic arch or proximal descending aorta, and c) extent A or C coverage.

In a 2007 prospective multicenter report from the European Collaborators on Stent/Graft Techniques for Aortic Aneurysm Repair (EUROSTAR) registry on 606 patients with endovascular repair of thoracic aorta pathologies (aneurysm, dissection, traumatic injury, anastomotic pseudoaneurysm and infectious/non specified), Buth, et al. found a 3.1% incidence of stroke16. Using multivariate regression analysis, female sex and duration of procedure > 160min were associated with an increased risk for stroke. This is likely related to lengthy manipulation of catheter, wires and devices within the aortic arch. Figure 3 demonstrates a completion angiogram from a patient on our service with an extent C aneurysm. A total of 5 devices were placed through an extremely tortuous anatomy. The patient suffered a perioperative left hemispheric stroke.

In a 2007 review of 153 patients, Khoynezhad, et al. reported a stroke rate of 4.3%17. Using univariate analysis, they found that obesity (body mass index > 30kg/m2), vascular thrombosis, embolization and significant blood loss carried a statistically significant risk for perioperative stroke.

Feezor, et al. reported on the risk factors for perioperative stroke during TEVAR18. The study included 196 patients treated with TEVAR with an incidence of 4.6%. Seven (78%) of these patients had coverage of zones 0-2, while only 2 (22%) had coverage of zones 3-4; all patients with coverage of zones 0 or 1 had an elective arch revascularization performed. Five out of these nine patients (55.6%) had documented intraoperative hypotension (systolic BP < 80mmHg). Six patients (66.7%) had posterior circulation strokes, all of them with zones 0-2 coverage, and only one of them underwent a carotid-subclavian bypass. Since January 2006, all the patients considered for LSA coverage underwent preoperative CTA or MRA of the head and neck for evaluation of the posterior cerebral circulation. Those patients with a dominant left vertebral artery or incomplete circle of Willis underwent a prophylactic carotid-subclavian bypass. The patients who underwent TEVAR before the institution of this policy had a stroke rate of 6.4%, which decreased to 2.3% after a preoperative imaging protocol was instituted (p=0.03). The authors concluded that stroke after TEVAR was multifactorial and appeared to be related to the coverage of the LSA and intraoperative hypotension. They recommended the elective revascularization of the LSA (carotid-subclavian bypass) in the setting of a dominant left vertebral artery or an incomplete circle of Willis.

Spinal cord ischemiaThe incidence of paraplegia/paraparesis after TEVAR is 3.4%, compared to 8.2% for open repair (p < 0.0001)13. The incidence of permanent paraplegia is also significantly different between the two modalities (1.4 vs. 4.9%; p=0.001). Spinal cord ischemia has been related to several risk factors, including aortic aneurysmal disease, extent of aortic repair or coverage19, previous abdominal aortic aneurysm repair20, compromised hypogastric artery inflow17, and left subclavian artery coverage16. Several diagnostic and therapeutic adjunctive methods have been used, including cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage, to reduce the arterial-CSF gradient21. On our service, all patients undergoing elective TEVAR for a descending thoracic aortic aneurysm receive a CSF drainage catheter intraoperatively. Due to our large thoracoabdominal experience, we have been able to carry out this protocol with a low (1.5%) complication rate22. The catheter is clamped and removed on postoperative day one if the patient remains neurologically intact. In patients who develop postoperative SCI, we drain the CSF to maintain a pressure < 10mmHg, transfuse to a target hemoglobin of 12gm/dl, and maintain a relatively high mean arterial pressure.

The EUROSTAR registry reported a SCI incidence of 2.5%16. The use of 3 or more stent grafts (correlating with the length of coverage) was significant in patients experiencing SCI (paraplegia-paraparesis) with 53 vs. 19% in the control group (p=0.009). Coverage and occlusion of the T10 level intercostal arteries was also more frequent in patients with SCI than in those without neurological symptoms (40 vs. 18%). LSA coverage was also found to be an important risk factor for neurological complications. LSA was covered in 159 patients, of whom 40 had a revascularization procedure (transposition or bypass). The group without LSA revascularization experienced a 40% incidence of paraplegia-paraparesis vs. 19% in the revascularized group. The rate of combined neurologic complications (paraplegia or stroke) was 8.4% in the group without LSA revascularization compared to a 0% rate in the revascularized group. Multivariate regression analysis showed independent correlation of SCI with the number of stent grafts used (> 3), coverage of the LSA, renal function impairment and simultaneous abdominal aortic repair. The authors recommended routine, prophylactic revascularization of the LSA in patients who required coverage of this vessel by the endograft at the proximal landing zone.

In a review of 153 patients, Khoynezhad, et al. report a 4.3% incidence. The most significant risk factors in this study for developing SCI were: aortic aneurysm, the need for an iliac conduit, and an occluded or excluded hypogastric artery17.

Complications involving the left subclavian artery coverageIn a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of neurological complications following TEVAR, all series reporting TEVAR without left subclavian artery (LSA) coverage were compared with LSA coverage with and without revascularization23. Compared with patients without LSA coverage, the risk of CVA was increased both in patients with LSA coverage alone (4.7 vs. 2.7; p=0.005) and in those with LSA coverage after revascularization (4.1 vs. 2.6%; p=0.02). The risk of SCI was also increased in patients requiring LSA coverage (2.8 vs. 2.3%; p=0.005) but not for LSA coverage after revascularization (0.8 vs. 2.7%; p=0.35). The authors concluded that the risk of neurologic complications is increased after coverage of the LSA during TEVAR. Preemptive revascularization offers no protection against CVA, perhaps indicating a heterogeneous etiology. Revascularization may reduce the risk of SCI, although limited data temper this conclusion.

Based on all available evidence, the current recommendations from the Society for Vascular Surgery Practice Guideline are as follows14:

- –

Recommendation 1: in patients who need elective TEVAR where achievement of a proximal seal necessitates coverage of the left subclavian artery, we suggest routine preoperative revascularization, despite the very low-quality evidence (grade 2, level C).

- –

Recommendation 2: in selected patients who have an anatomy that compromises perfusion to critical organs, routine preoperative LSA revascularization is strongly recommended, despite the very low-quality evidence (grade 1, level C).

- –

Recommendation 3: in patients who need urgent TEVAR for life-threatening acute aortic syndromes where achievement of a proximal seal necessitates coverage of the left subclavian artery, we suggest that revascularization should be individualized and addressed expectantly on the basis of anatomy, urgency, and availability of surgical expertise (grade 2, level C).

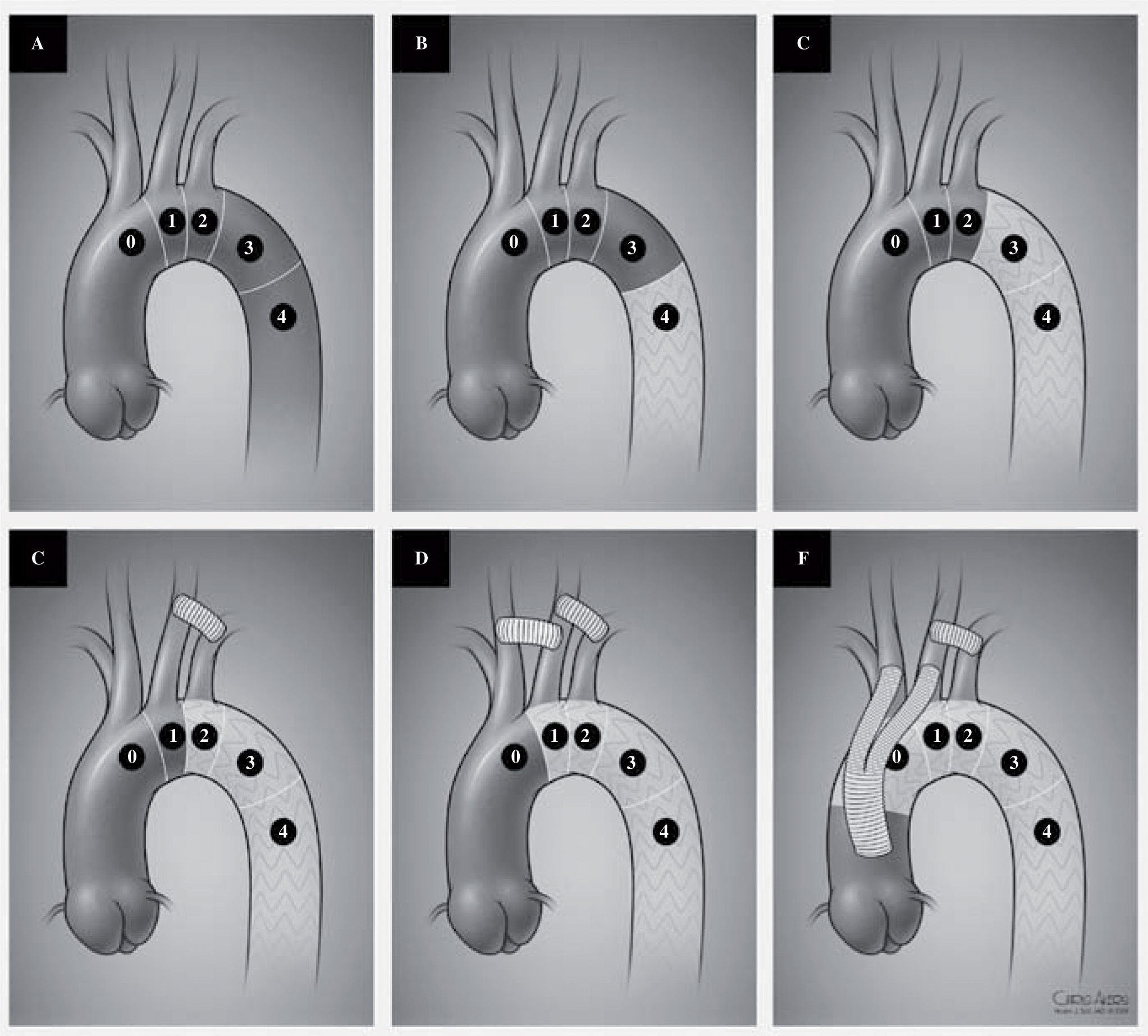

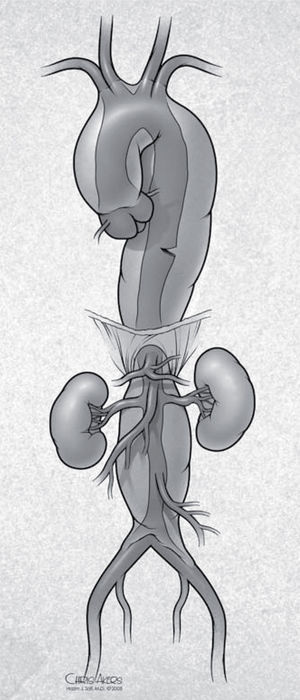

Retrograde type A aortic dissection (RAAD) is a rare and lethal complication of TEVAR procedures. It is defined as an intimal tear distal to the transverse arch with retrograde extension into the ascending aorta (Fig. 4). The risk for RAAD after TEVAR has been reported between 1.9 to as high as 6.8% in single-center series24–26. In these studies, RAAD has been related to several factors, including: a) the TEVAR procedure itself (trauma caused by manipulation of wires/sheaths and stent graft balloon dilatation, large bore stent graft delivery system); b) device properties (semi-rigidity and proximal bare spring, excessive radial force due to oversizing > 20%); c) aortic wall friability (acute/chronic aortic dissection), and d) connective tissue diseases (Marfan syndrome, Ehler Danlos syndrome).

Eggebrecht, et al.27 analyzed the 13-year experience from the European Registry on Endovascular Aortic Repair Complications, reporting an RAAD incidence of 1.33% (63/4,750 cases). Of these, 48 patients (48/3,714 cases) had complete data sets for the analysis. Thirty-nine of the 48 patients (81%) underwent TEVAR for aortic dissection (acute 54%, chronic 27%). TEVAR was performed as an emergency in 16 (33%) patients and electively in 32 (67%). Four patients (8%) had Marfan syndrome. Forty patients (83%) had a proximal bare spring stent graft placed. RAAD occurred during the TEVAR procedure in 7 patients (15%), before the procedure during the index hospitalization in 10 (21%), and after discharge during follow-up in 31 (65%) patients. In 22 patients (46%), RAAD occurred within 30 days after the procedure and beyond 3 months in 15 patients (31%), with a median of 35 days (range 0-1,050 days). Among the cohort, 58% of the patients experienced symptoms (chest pain or syncope), 19% had sudden death, and 25% were asymptomatic. Management consisted of emergency surgical repair in 25 patients (64%) and elective surgery in 5 patients (13%). Nine patients (23%) were treated medically with anti-impulse therapy. Overall mortality was 42% (20/48 patients). Causes included the stent graft (60%), manipulation of guide wires and sheaths (15%), and progression of underlying aortic disease (15%). The majority of the RAAD cases were reportedly associated with the use of proximal bare spring stent grafts, with direct evidence of device-related injury at surgery or autopsy in half of the patients.

Dong, et al.28 reported a 2.5% (11 patients) incidence of RAAD in a series of 443 patients treated with TEVAR for type B dissection (acute 25%, chronic 75%). The stent grafts were landed in zones 2 (2 patients) and 3 (9 patients). RAAD developed intraoperatively in 2 patients and postoperatively in the rest (2 h to 36 months). Clinical manifestations included syncope, hypotension, dyspnea, hypoxemia, chest pain and sudden death. Three patients had Marfan syndrome. The site of new entry was identified at the tip of the proximal bare spring in 9 patients (81.1%) and within the area of anchorage in 1 patient by intraoperative angiogram, CT or open surgery. Three patients died perioperatively (27.3%). Authors concluded that RAAD is not a rare complication after endovascular repair of type B aortic dissection. Predisposing factors may include aortic wall fragility, disease progression, and stent graft-related causes.

Device malfunctionIn relation to the abdominal aorta, the complexity of device delivery and deployment in the thoracic aorta is related to several factors including larger hemodynamic forces, more tortuous anatomy, and larger devices delivered over a relatively longer distance. In a comprehensive summary of failure modes of aortic endografts, Lee discusses their prevention and management29. Intraoperative factors include inability to advance the delivery system, unintended device movement and maldeployment30. Device infolding is likely related to oversizing and/or lack of apposition to the inner curvature of the aortic arch. This has been reported in the literature and can usually be salvaged with endovascular techniques. Additional endografts and bare stents can be placed to increase the radial force31,32. Finally, all endografts are subject to material failure. These include metal fractures and fabric tears. This further highlights the need for long-term surveillance imaging of all endovascular aortic repairs.

Access complicationsVascular complications have been reported in 13% of patients undergoing TEVAR13. These complications include arterial thrombosis, occlusion, dissection, or rupture (“iliac on a stick”), hematoma, pseudoaneurysm, arteriovenous fistula, retroperitoneal bleeding, embolism, and wound infection. Some vascular disease is inherently present in many patients undergoing TEVAR. Attention to proper surgical and endovascular techniques is paramount. Liberal use of iliac conduits in patients with borderline anatomy cannot be overemphasized. This further underlines the necessity of performing these procedures in an operating room by a team that is well versed in open and endovascular bail-out techniques to address these complications.

EndoleakEndoleak remains one of the principal reasons for endovascular repair failure. It is defined as persistent blood flow outside the endograft and within the aneurysm sac, and it is classified in four types33:

- I

a) inadequate seal at proximal end of endograft, and b) inadequate seal at distal end of endograft.

- II

flow from vessel without attachment site connection (intercostals, LSA, bronchial arteries).

- III

a) flow from module disconnection, and b) flow from fabric disruption.

- IV

flow from porous fabric (> 30 days after graft placement).

There is paucity of information on the true incidence of endoleaks outside of the few clinical trials. The overall incidence of endoleaks from a meta-analysis of reported studies is 12.1%13. This, however, may be an overestimate, as many studies do not report endoleaks. The results of the three published US trials are summarized below:

- –

Makaroun, et al., in the WL Gore TAG pivotal trial34, compared 5-year results of TEVAR with the TAG device (n=191) to surgical controls (n=94). Endoleak occurred in 10.6% of patients at some point during the 5-year follow-up. Most endoleaks were thought to be type I. Three patients required five endovascular reinterventions for endoleaks. These additional procedures took place from 45-1,525 days after the original repairs.

- –

Fairman, et al., in the VALOR Trial12, reported the results of TEVAR using the Medtronic Vascular Talent Thoracic Stent Graft System (Medtronic Vascular, Santa Rosa, CA). Among the 195 patients enrolled, the incidence of endoleak at 1 month follow-up was 25.9% (type I: 4%; type II: 15.5%; type III: 1.7%; type IV: 0%). Fourteen procedures were performed to resolve the endoleak. At the 12-month follow-up, the incidence of endoleak was 12.2% (types I: 4.9%; type II: 4.9%; type III and IV: 0%).

- –

Matsumura, et al. reported the results of TEVAR in the Zenith TX2 (William Cook, Europe) trial11. The outcomes of 160 TEVAR patients using the Zenith TX2 graft were compared to 70 patients treated with open surgery. The incidence of endoleak at predischarge, 30 days, 6 and 12 months were 13, 4.8, 2.6, and 3.9%, respectively. Most of the endoleaks were type II. Most type I and III endoleaks were addressed in the first year with endovascular reintervention, and none required conversion. Overall, 4.4% of patients underwent secondary procedures through 12 months of follow-up.

Morales, et al.35, in a retrospective review of 200 TEVAR patients for the etiology and outcomes of endoleaks at the Cleveland Clinic, found a 19.5% (39/200) incidence of endoleaks in follow-up (mean of 30 months). These were classified as primary or secondary depending on whether they were noted or not in the first post-implantation CT. Fourteen patients developed a type I endoleak (11 primary and 3 secondary), seven developed a type III (5 primary and 2 secondary); these were treated with a secondary endovascular intervention or conservatively. Sixteen patients developed a type II endoleak (13 primary and 3 secondary), thought to arise from the intercostal arteries, patent covered LSA, celiac and bronchial arteries. Glue embolization was performed in three patients with covered LSA endoleak, the rest were treated conservatively. The factors associated with endoleaks were presence of a carotid-LSA bypass (p=0.0001), and longer aortic coverage by the stent graft (p=0.005). Authors concluded that conservative treatment is adequate for type II endoleaks, while most type I and III endoleaks require a secondary intervention.

MigrationMigration is defined as a > 10mm movement of the endograft relative to anatomical landmarks, or any migration leading to symptoms or requiring therapy33. Similar to the data on endoleak, there is a paucity of information outside clinical trials on device migration.

In the Gore TAG trial, migration occurred in one patient (incidence of 0.7%)34. This patient underwent an open arch aneurysm repair for endoleak and migration at 5 months. The authors linked this to poor proximal neck anatomy. In the Medtronic VALOR trial, four stent graft migrations were reported in 12 months (incidence 2.1%)12. Two migrations involved the proximal end of the graft moving distally, and two involved the distal end of the graft moving proximally. One of these patients reportedly required an additional intervention related to the migration. In the Cook TX2 trial, migration was reported in 2.8% of patients at 12 months follow-up. There were two cases of caudal migration of the proximal graft and one case of cranial migration of the distal graft. These cases were not associated with endoleak or increase in aneurysm diameter. None of the patients required a secondary intervention11.

ConclusionThoracic endovascular repair is an excellent alternative to open surgery in properly selected patients with descending thoracic aortic aneurysms. The accumulated evidence shows that TEVAR can reduce mortality, paraplegia, and overall complications compared with open surgery. The long-term survival, durability and cost effectiveness of TEVAR remains to be determined. Appropriate recognition and management of TEVAR complications can improve long-term outcome of these patients.

IntroducciónLos aneurismas de la aorta son la decimotercera causa de muerte en EE.UU. Su prevalencia parece incrementarse por un conocimiento difundido, mejoras en las técnicas de imagen, y edad avanzada de la población1. La incidencia de aneurismas torácicos (AAT) es de 5,9 nuevos casos/100.000 personas/año2. La edad media en el momento del diagnóstico es de 59-69 años, con una razón de género masculino 2:1-4:13. La historia natural sugiere que, tras el diagnóstico, el 74% de los AAT se rompen en un intervalo mediano de 2 años (1 mes - 16 años)2. Los pacientes con AAT tienen otras comorbilidades como: hipertensión, enfermedad coronaria, enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica e insuficiencia cardíaca3. Los AAT descendentes se clasifican en tres tipos (Fig. 1): extensión A (subclavia izquierda a 6.a costilla, extensión B (6.a costilla a diafragma) y extensión C (subclavia a diafragma)4.

Desde la década de 1950, la reparación quirúrgica abierta ha sido el tratamiento principal de los AAT. Ello implica toracotomía, oclusión aórtica y pérdida de sangre con impacto potencial sobre corazón, pulmón, riñón, cerebro y médula espinal. Este abordaje se asocia con morbimortalidad significativa y resultados variables en diferentes centros5–8. La reparación endovascular torácica (TEVAR) se desarrolló en la década de 1990 para los AAT9, y la Food and Drug Administration (FDA) aprobó el primer dispositivo en 200510, con la aprobación ulterior de dos más11,12. En los tres ensayos, TEVAR se comparó favorablemente con la reparación abierta en aneurismas degenerativos. En la actualidad se tratan con TEVAR aneurismas más complejos (Fig. 2). Un metaanálisis reciente confirmó que TEVAR, en comparación con la cirugía abierta, puede reducir la tasa de muerte, paraplejía, insuficiencia renal, transfusiones, reoperación por hemorragia, complicaciones cardíacas, neumonía y estancia hospitalaria13. Esta revisión quiere hacer hincapié en las complicaciones del procedimiento, es decir, mortalidad, accidente cerebrovascular, isquemia medular, disección retrógrada, disfunción del material, complicaciones del acceso, endofugas y migración.

ComplicacionesMortalidadEn un metaanálisis de 42 estudios no aleatorizados (38 comparativos, 4 registros) con 5.888 pacientes, el riesgo de mortalidad a 30 días fue 5,8% para TEVAR comparado con 13,9% para la cirugía abierta (p < 0,00001)13. La mortalidad acumulada de cualquier causa a 1, 2 y 3 años no tuvo diferencias estadísticas entre grupos. Si bien los pacientes TEVAR fueron significativamente de edad más avanzada, las otras características basales no difirieron entre los grupos.

Accidente vascular cerebralSi bien TEVAR tiene un patrón de complicaciones único entre los procedimientos endovasculares, el accidente vascular cerebral (AVC) tiene una frecuencia similar a la de la cirugía abierta (6,2 vs 5%)13>. El AVC es la complicación más temida y devastadora, y puede estar relacionada con factores sistémicos (hipotensión, hipertensión, anticoagulación), causas intracraneales (hemorragia, edema, drenaje de líquido cefalorraquídeo [LCR]) o embolias (aire, ateroma, trombo)14.

La embolización puede relacionarse con las guías, catéteres y dispositivos en una aorta y arco ateromatosos, con dislocamiento de placas que se dirijan al cerebro. Los pacientes con ateromatosis generalizada y con aneurismas cercanos al arco tienen un riesgo superior. En una revisión de 2007 de 171 pacientes tratados con TEVAR, Gutsche, et al. comunicaron una incidencia de infarto cerebral de 5,8%15. La ateromatosis aórtica grave (protrusión > 5mm en la aorta) se encontró en siete de ocho pacientes infartados, y se asoció claramente con AVC (p=0,016). La historia de AVC y extensión tipo A tenía una incidencia de AVC del 60%, mientras que en la extensión tipo C era del 15%. Tras la revisión de estos datos, se identificaron tres factores para infarto cerebral perioperatorio: a) historia preoperatoria de infarto cerebral; b) ateroma grado IV (> 5mm) en el arco o aorta torácica descendente (ATD), y c) extensión A o recubrimiento C.

En un estudio prospectivo multicéntrico de 2007, el registro EUROSTAR, con 606 pacientes tratados para reparación de la aorta torácica por diversas enfermedades, Bluth, et al. encontraron una incidencia de 3,1%16. Un análisis de regresión multivariado demostró que el género femenino y la duración del procedimiento superior a 160min se asociaron con un riesgo incrementado, lo que se relaciona con la manipulación de guías, catéteres y dispositivos en el arco aórtico. La figura 3 demuestra una angiografía de un paciente nuestro con aneurisma de extensión C. Se colocaron cinco dispositivos en una anatomía tortuosa y el paciente presentó infarto hemisférico izquierdo.

En una revisión de 2007 sobre 153 pacientes, Khoynezhad, et al. comunicaron una incidencia de 4,3%17. El análisis univariado identificó que la obesidad (índice de masa corporal [IMC] > 30), trombosis vascular, embolia y pérdida de sangre tenían un riesgo estadísticamente significativo de AVC.

Feezor, et al. comunicaron sobre los factores de riesgo para AVC perioperatorio en TEVAR18. Incluyeron 196 pacientes con TEVAR con una incidencia de 4,6%. Siete (78%) de ellos tenían recubrimiento de zonas 0-2, mientras que sólo dos (22%), recubrimiento de zonas 3-4: todos los pacientes con recubrimiento de zonas 0-1 fueron sometidos a revascularización electiva del arco. Cinco de estos nueve pacientes (55,6%) tuvieron hipotensión intraoperatoria documentada (tensión arterial sistólica [TAS] < 80mmHg). Seis pacientes (66,7%) tuvieron infartos de circulación posterior, todos con recubrimiento de zonas 0-2, y en sólo uno se realizó derivación carotidosubclavia. Desde enero de 2006, todos los pacientes propuestos para recubrimiento de subclavia izquierda fueron sometidos a angiotomografía o angiorresonancia de cabeza y cuello para evaluar la circulación cerebral posterior. Los pacientes con vertebral izquierda dominante o círculo de Willis incompleto se sometieron a derivación carotidosubclavia. Los pacientes con TEVAR antes de esta política tuvieron una tasa de infarto cerebral de 6,4% que disminuyó a 2,3% (p=0,03) tras este protocolo. Los autores concluyeron que TEVAR es multifactorial y que parecía relacionado con el recubrimiento subclavio e hipotensión, por lo que recomendaron la derivación carotidosubclavia profiláctica en estos pacientes.

La incidencia de paraplejía/paraparesia después de TEVAR es 3,4 frente a 8,2% de la reparación abierta (p < 0,0001)13. La incidencia de paraplejía permanente es también diferente entre modalidades (1,4 vs 4,9%; p=0,001). La isquemia medular se relaciona con diversos factores como aneurisma de aorta abdominal (AAA), extensión del recubrimiento aórtico19, reparación previa de AAA20, flujo comprometido de la arteria hipogástrica17 y recubrimiento de la subclavia izquierda16. Se han utilizado ciertos métodos adjuntos como el LCR para reducir el gradiente arterial-LCR21. En nuestro servicio, a todos los pacientes sometidos a TEVAR electivo por aneurisma de aorta torácica descendente (AAT) se les coloca un catéter de drenaje de LCR. Por nuestra amplia experiencia toracoabdominal, hemos podido realizar este protocolo con una baja tasa de complicación (1,5%)22. El catéter se ocluye y se retira en el primer día postoperatorio si no hay sintomatología neurológica. En los pacientes con isquemia medular postoperatoria, drenamos LCR para mantener una presión inferior a 10mmHg, se transfunden hasta una hemoglobina de 12 g/dl y se mantiene una presión arterial media alta.

El registro EUROSTAR comunicó una tasa de isquemia medular de 2,5%16. El uso de tres o más stents (correlacionado con la extensión del recubrimiento) fue significativo en pacientes que presentaron isquemia medular, 53 frente a 19% en el grupo control (p=0,009). El recubrimiento y oclusión de intercostales a nivel T10 fue más frecuente en pacientes con isquemia medular (40 vs 18%). El recubrimiento de la subclavia izquierda fue un factor importante de riesgo de complicaciones neurológicas. Se recubrió en 159 pacientes, de los 40 recibieron una transposición o derivación. Cuando no hubo revascularización, la incidencia de isquemia medular fue 40 frente a 19%. La tasa combinada de eventos neurológicos (paraplejía + AVC) fue 8,4 frente a 0% en el grupo revascularizado. El análisis multivariado de regresión mostró una correlación independiente de isquemia medular con el número de stents (> 3) utilizados, recubrimiento de la subclavia, insuficiencia renal y reparación simultánea de aneurisma abdominal. Los autores recomendaron revascularización rutinaria profiláctica de la subclavia en pacientes que requerían oclusión intencionada por la endoprótesis en la zona proximal de anclaje.

En una revisión de 153 pacientes, Khoynezhad, et al. comunicaron una incidencia de 4,3%. Los factores de riesgo más significativos para isquemia medular fueron: aneurisma aórtico, necesidad de conducto ilíaco y arteria hipogástrica excluida.

Complicaciones que involucran el recubrimiento de la arteria subclavia izquierdaEn un reciente metaanálisis de las complicaciones neurológicas después de TEVAR, en todas las series con TEVAR sin recubrimiento de subclavia se compararon las recubiertas con y sin revascularización23. El riesgo de AVC aumentó en los pacientes con sólo recubrimiento (4,7 vs 2,7%; p=0,005) y en los que tenían recubrimiento después de la revascularización (4,1 vs 2,6%; p=0,02). El riesgo de isquemia medular fue superior en pacientes que requirieron recubrimiento (2,8 vs 2,3%; p=0,005) pero no para recubrimiento después de la revascularización (0,8 vs 2,7%; p=0,35). Los autores concluyeron que el riesgo de complicaciones neurológicas está aumentado después del recubrimiento de subclavia durante TEVAR. La revascularización profiláctica no ofrecía protección contra AVC, quizás indicando una etiología heterogénea. La revascularización podría reducir el riesgo de isquemia medular, si bien los datos disponibles son escasos.

Basadas en la evidencia disponible, las recomendaciones actuales de la Society for Vascular Surgery Practice Guideline son las siguientes14:

- –

Recomendación 1: en pacientes que necesitan TEVAR electivo donde el sello proximal necesita de recubrimiento subclavio, sugerimos la revascularización preoperatoria rutinaria a pesar de la evidencia de muy baja calidad (grado 2, nivel C).

- –

Recomendación 2: en pacientes seleccionados con anatomía que compromete la perfusión de órganos críticos, se recomienda la revascularización subclavia preoperatoria rutinaria a pesar de evidencia de baja calidad (grado 1, nivel C).

- –

Recomendación 3: en pacientes que requieren TEVAR urgente por síndrome aórtico agudo de alto riesgo vital, cuando el sello distal necesita recubrimiento subclavio, sugerimos revascularización individualizada y conducta expectante en función de la anatomía, urgencia y disponibilidad de experiencia quirúrgica (grado 2, nivel C).

La disección tipo A retrógrada (TAR) es una complicación rara y letal de TEVAR. Se define como un defecto de la íntima distal al arco con extensión retrógrada en la aorta ascendente (Fig. 4). El riesgo de TAR después de TEVAR está entre 1,9-6,8% en series institucionales24–26. En estos estudios la TAR se ha relacionado con diversos factores como: a) el procedimiento TEVAR en sí mismo (trauma por manipulación de guías/alambres y dilatación de balón, sistemas de liberación de gran calibre); b) propiedades de los dispositivos (semirrigidez, fuerza radial excesiva debido a sobredilatación > 20%); c) friabilidad de la pared de la aorta (disección aguda/crónica), y d) enfermedades del tejido conectivo (Marfan, Ehlers-Danlos).

Eggebrecht, et al.27 analizaron la experiencia de 13 años del European Registry on Endovascular Aortic Repair Complications comunicando una incidencia de TAR del 1,33% (63/4.750 casos). De éstos, 48 pacientes (48/3.714 casos) tenían información completa. Treinta y nueve de 48 (81%) recibieron TEVAR por disección de aorta (aguda 54%, crónica 27%), TEVAR fue urgente en 16 (33%) y electiva en 32 (67%). Cuatro pacientes (8%) tenían síndrome de Marfan. Cuarenta pacientes (83%) tenían un stent proximal no recubierto. TAR ocurrió durante TEVAR en siete pacientes (15%), antes del procedimiento en el ingreso en 10 (21%), y después del alta en 31 (65%). En 22 (46%), TAR ocurrió en 30 días después del procedimiento y después de 3 meses en 15 (31%), con una mediana de 35 días (0-1050 días). En el grupo, el 58% tuvo síntomas (dolor torácico o síncope), 19% muerte súbita y 25% estaban asintomáticos. El manejo consistió en intervención urgente en 25 (64%) y electiva en cinco (13%). Nueve pacientes (23%) fueron tratados médicamente con terapia antiimpulso. La mortalidad global fue 42% (20/48). Las causas incluyeron el propio stent (60%), manipulación de guías y vainas (15%), y progresión de la enfermedad aórtica (15%). La mayoría de casos de TAR se asociaron con stents no recubiertos con evidencia de lesión relacionada con el dispositivo en la mitad de los pacientes en el estudio post mortem.

Dong, et al.28 comunicaron una incidencia de TAR de 2,5% (11 pacientes) en una serie de 443 pacientes tratados con TEVAR por disección tipo B (aguda 25%, crónica 75%). Las endoprótesis se liberaron en las zonas 2 (2 pacientes) y 3 (9 pacientes). TAR se desarrolló durante el procedimiento en dos pacientes y después en el resto (2 h - 36 meses). Las manifestaciones clínicas incluyeron: síncope, disnea, hipoxia, dolor torácico y muerte súbita. Tres pacientes tenían síndrome de Marfan. El lugar de entrada se identificó en el extremo proximal del stent en nueve pacientes (81,1%), y en el área de anclaje en uno mediante angiografía intraoperatoria, tomografía o en cirugía abierta. Tres pacientes fallecieron (27,3%). Los autores concluyeron que TAR no es una complicación rara después de TEVAR por disección tipo B. Los factores predisponentes podrían ser: fragilidad de la pared aórtica, progresión de la enfermedad y causas relacionadas con el dispositivo.

Disfunción del dispositivoEn relación con la aorta abdominal, la complejidad de la liberación en la aorta torácica se relaciona con diversos factores como fuerzas hemodinámicas superiores, anatomía más tortuosa y dispositivos de mayor tamaño liberados en una distancia relativamente larga. En una revisión de los modos de fallo de las endoprótesis aórticas, Lee discutió su prevención y manejo29. Los factores intraoperatorios incluyen la incapacidad de avanzar el sistema de liberación, movimientos no intencionados y mala liberación30. La invaginación del dispositivo puede relacionarse con la sobredimensión y/o falta de aposición sobre la curvatura interna del arco. Esto puede solucionarse mediante técnica endovascular. Dispositivos adicionales pueden implantarse para aumentar la fuerza radial31,32. Finalmente, todas las endoprótesis están sometidas a fallo del material incluyendo fracturas del metal y defectos en el tejido, lo que confirma la necesidad de control permanente de las endoprótesis.

Complicaciones del accesoSe ha comunicado una tasa del 13% de complicaciones vasculares en pacientes TEVAR13. Éstas incluyen: trombosis arterial, oclusión, disección o ruptura, hematoma, falso aneurisma, fístula arteriovenosa, hemorragia retroperitoneal, embolia e infección de la herida. Un cierto grado de enfermedad vascular está presente en muchos pacientes TEVAR. La atención a una técnica quirúrgica y endovascular apropiada es crítica. El uso libre de conductos ilíacos en pacientes con anatomía marginal debe considerarse. Ello apoya necesariamente que estos procedimientos se realicen en un quirófano por un equipo familiarizado con las técnicas abiertas y endovasculares de rescate.

EndofugaLa endofuga sigue siendo una de las principales razones del fallo de la reparación endovascular. Se define como el flujo persistente fuera de la endoprótesis y dentro del saco aneurismático, y se clasifica en cuatro tipos33:

- I

a) sello inadecuado en el extremo proximal de la endoprótesis, y b) sello inadecuado en el extremo distal.

- II

flujo a partir de un vaso sin conexión a la zona de conexión (intercostales, subclavia izquierda, arterias bronquiales).

- III

a) flujo a partir de desconexión del módulo, y b) flujo desde una ruptura del tejido.

- IV

flujo a partir del tejido poroso (> 30 días del implante).

Existe escasa información sobre la incidencia real de endofuga más allá de los ensayos clínicos. La incidencia global de endofuga en un metaanálisis es del 12,1%13. Esto podría ser una sobrestimación, ya que muchos estudios no comunican endofuga. Los resultados de tres estudios norteamericanos publicados se resumen así:

- –

Makaroun, et al., en el ensayo WL Gore TAG34, compararon los resultados de TEVAR a 5 años con el sistema TAG (n=191) frente a controles quirúrgicos (n=94). Aparecieron endofugas en 10,6% durante un seguimiento de 5 años. La mayoría fueron tipo I. Tres pacientes requirieron cinco intervenciones endovasculares por endofugas. Estos procedimientos adicionales se realizaron entre 45-1.525 días tras la reparación.

- –

Fairman, et al., en el ensayo VALOR12, comunicaron los resultados de TEVAR con el sistema Talent Medtronic (Medtronic Vascular, Santa Rosa, CA, USA). Entre los 195 pacientes incluidos, la incidencia de endofuga al mes fue del 25,9% (tipo I: 4%; tipo II: 15,5%; tipo III: 1,7%; tipo IV: 0%). Se realizaron 14 procedimientos por la fuga. A los 12 meses, la incidencia de endofuga fue 12,2% (tipo I: 4,9%; tipo II: 4,9%, tipos III y IV: 0%).

- –

Morales, et al.35, en una revisión retrospectiva de 200 TEVAR en cuanto a etiología y resultados de las endofugas en la Cleveland Clinic, encontraron una incidencia de 19,5% (39/200) en el seguimiento (media 30 meses). Se clasificaron en primarias o secundarias según se encontraran o no en la primera tomografía de postimplante. Catorce pacientes desarrollaron una endofuga tipo I (11 primaria y 3 secundaria), siete una tipo III (5 primaria, 2 secundaria); éstas fueron tratadas con intervención endovascular o de forma conservadora. Dieciséis pacientes tuvieron una endofuga tipo II (13 primaria, 3 secundaria) a partir de arterias intercostales, subclavia recubierta permeable, arteria celíaca o bronquiales. Se realizó embolización en tres casos con endofuga en subclavias recubiertas. Los factores asociados con endofugas fueron las derivaciones carotidosubclavias (p=0,0001) y recubrimiento aórtico largo por la endoprótesis (p=0,005). Los autores concluyeron que el tratamiento conservador es adecuado en las endofugas tipo II, mientras que la mayoría de las tipo I y III requieren reintervención.

La migración se define como un desplazamiento de más de 10mm de la endoprótesis en relación con las marcas anatómicas, o cualquier migración que conduzca a síntomas o requiera tratamiento33. Como en las endofugas, existe escasa información fuera de los ensayos clínicos.

En el ensayo Gore TAG, apareció migración en un paciente (0,7%)34. Este paciente recibió reparación abierta de un aneurisma de arco por endofuga y migración a los 5 meses. Los autores lo relacionaron con anatomía desfavorable del cuello. En el ensayo Medtronic VALOR se comunicaron cuatro migraciones en 12 meses (2,1%)12. Dos migraciones afectaban al extremo proximal, que se desplazó distalmente, y dos el extremo distal, que se desplazó proximalmente. Uno de los pacientes requirió reintervención. En el ensayo Cook TX2, la migración fue del 2,8% a los 12 meses. Hubo dos casos no asociados con endofuga o aumento del tamaño del aneurisma. Ninguno requirió una reintervención11.

ConclusiónLa reparación endovascular torácica es una alternativa excelente a la cirugía abierta en pacientes con aneurismas de aorta torácica descendente adecuadamente seleccionados. La evidencia acumulada muestra que TEVAR puede reducir la mortalidad, paraplejía y la tasa global de complicaciones con respecto a la cirugía abierta. La supervivencia, durabilidad y coste-eficiencia de TEVAR queda por determinar. El reconocimiento y manejo apropiados podría mejorar los resultados alejados de estos pacientes.