Artificial intelligence (AI) and computer vision (CV) are increasingly applied in vascular surgery for preoperative mapping and intraoperative flow/perfusion assessment, with potential to enhance safety and efficiency. However, the extent of their clinical validation and generalizability remains unclear. To synthesize current evidence on AI/CV applications in vascular surgery, focusing on quantitative clinical and technical outcomes, and to identify methodological gaps hindering widespread adoption. A narrative review was conducted by PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus and complemented with ELICIT, Web of Science, and IEEE Xplore searches. Eligible studies (last 5 years, English/Spanish) included narrative/systematic reviews, clinical trials, observational, and experimental studies with clinical evaluation. Applications considered were preoperative vascular mapping, intraoperative flow/perfusion assessment, and anastomosis assistance/verification. Data extracted included study design, CV/AI technique, sample size, outcomes (diagnostic accuracy, time reduction, radiation/contrast use, complication rates), and performance metrics. Ten studies met inclusion criteria: 7 addressed preoperative mapping, 5 intraoperative flow/perfusion, and 4 anastomosis assistance (some covering multiple domains). Reported benefits included reductions in radiation exposure (up to 48%), contrast use (up to 38%), and operative time (up to 10%), as well as high diagnostic accuracy (median AUROC 0.88) and real-time guidance capabilities. Limitations included predominance of retrospective, single-center designs, scarce external validation (<5% of studies), reliance on single data modalities, and suboptimal adherence to reporting standards. Artificial intelligence and computer vision tools show promise in improving procedural efficiency and safety in vascular surgery, but robust multicenter, prospectively validated studies are needed to confirm their clinical value and enable broad implementation.

La inteligencia artificial (IA) y la visión por computador (VC) se aplican cada vez más en cirugía vascular para el mapeo preoperatorio y la evaluación intraoperatoria del flujo/perfusión, con potencial para mejorar la seguridad, la eficiencia y finalmente la atención del paciente. Sin embargo, el grado de validación clínica y la generalización de estas herramientas siguen sin estar claros. El objetivo del estudio fue sintetizar la evidencia actual sobre aplicaciones de IA/VC en cirugía vascular, enfocándose en resultados clínicos y técnicos cuantitativos, e identificar brechas metodológicas que limitan su adopción generalizada. Se realizó una revisión narrativa mediante búsquedas en PubMed/MEDLINE y Scopus, complementadas con ELICIT, Web of Science e IEEE Xplore. Se incluyeron estudios elegibles (últimos 5 años, en inglés o español) revisiones narrativas/sistemáticas, ensayos clínicos, estudios observacionales y experimentales con evaluación clínica. Las aplicaciones consideradas fueron mapeo vascular preoperatorio, evaluación intraoperatoria del flujo/perfusión y asistencia/verificación de anastomosis. Se extrajeron datos sobre diseño del estudio, técnica de IA/VC, tamaño de muestra, desenlaces (exactitud diagnóstica, reducción de tiempo, uso de radiación/contraste, tasas de complicaciones) y métricas de desempeño. Diez estudios cumplieron criterios de inclusión: 7 abordaron mapeo preoperatorio, 5 evaluación intraoperatoria del flujo/perfusión y 4 asistencia en anastomosis (algunos cubrieron múltiples dominios). Los beneficios reportados incluyeron reducciones en exposición a radiación (hasta 48%), uso de contraste (hasta 38%) y tiempo operatorio (hasta 10%), así como alta exactitud diagnóstica (AUROC mediano 0,88) y capacidades de guía en tiempo real. Las limitaciones incluyeron predominio de diseños retrospectivos y unicéntricos, escasa validación externa (<5% de los estudios), dependencia de modalidades únicas de datos y adherencia subóptima a los estándares de reporte. Las herramientas de IA/VC muestran potencial para mejorar la eficiencia y la seguridad de los procedimientos en cirugía vascular; no obstante, se requieren estudios multicéntricos y robustos con validación prospectiva para confirmar su valor clínico y posibilitar una implementación amplia.

Accurate intraoperative flow and perfusion assessment is critical in vascular surgery, where many procedures involve high-risk patients with complex comorbidities.1 Current standard methods for vessel planning and intraoperative guidance—such as fluoroscopy and conventional angiography—are associated with substantial ionizing radiation exposure and contrast media use.2 Additionally, these techniques can be time-consuming and subjective, particularly during preoperative mapping of complex vascular anatomies such as perforator vessels,3 and may be affected by anatomical deformation during procedures, which can compromise image registration accuracy.4

Artificial intelligence (AI) and computer vision (CV) have emerged as transformative technologies in surgery, offering the ability to analyze large datasets, enhance diagnostic accuracy, and improve workflow efficiency.1 In vascular surgery, AI-assisted fusion imaging and augmented reality have demonstrated notable clinical benefits, including significant reductions in radiation exposure (up to 48%) and contrast use (up to 38%) during complex aneurysm repair,5–7 high diagnostic accuracy in vessel planning (median AUROC 0.88),1 and qualitative workflow improvements without increasing complication rates.8 Despite these promising applications, translation into routine clinical practice remains limited.1 Critical appraisal of the literature reveals pervasive methodological shortcomings: 94.8% of reviewed studies present a high risk of bias, often due to inadequate reporting of missing data, lack of model calibration, and failure to address overfitting.1 Most are retrospective, single-center studies, with few prospectively tested models and a complete absence of randomized controlled trials.1,6 External validation is rare (<5% of studies), undermining generalizability.1 Additional barriers include reliance on single data modalities rather than multimodal data fusion, insufficient demographic reporting (<20% of studies), variability in software accuracy by vessel size,3 and low model transparency with limited methodological detail and lack of open-source code.1

Given these significant evidence gaps and the nascent stage of robust clinical validation, a comprehensive narrative review is warranted. This article synthesizes current evidence on AI and CV applications in preoperative vascular mapping and intraoperative flow/perfusion assessment, critically examines methodological limitations, and outlines priorities for future research to support safe, effective, and widely applicable clinical integration.

MethodsThis narrative review was conducted in accordance with the Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA), aiming to maximize the quality score (12/12 points). All six SANRA domains—justification of the article's importance, statement of concrete aims, literature search, referencing, scientific reasoning, and appropriate presentation of data—were addressed.

Brief technical overviewIncluded studies used AI/CV techniques such as CNN/U-Net/ResNet-type models for classification/segmentation, 2D/3D CTA–fluoroscopy fusion with rigid/deformable registration, cloud-based intelligent surgical overlays, and lightweight models (MobileNetV2) for intraoperative prediction. Operational definitions are provided in Appendix A, and applications/metrics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Summary of included studies on computer vision (CV) and artificial intelligence (AI) applications in vascular surgery.

| Author (year) | Study design | Application domain | CV/AI technique | Key quantitative outcomes | Performance metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al.1 | Systematic review | Preoperative mapping | Neural networks (CNN) | Not reported | Median AUROC=0.88 (range 0.61–1.00) |

| Patel et al.6 | Retrospective cohort | Preoperative mapping, Intraoperative flow, Anastomosis | AI surgical overlay | Significant reduction in radiation, contrast, operative time (raw values not provided) | Comparative metrics in Table 2 |

| Patel et al.5 | Retrospective cohort | Intraoperative flow | AI intelligent maps | Radiation: −48% (3755–1955mGy, P=.004); Contrast: −38% (199–123mL, P<.0001); Operative time: −10% (284–255min, P=.294) | Not reported |

| Wegner et al.9 | Retrospective cohort | Preoperative mapping | Deep learning (ARVA) | Median error: 2.4mm (pre), 1.6mm (post) | 89% accuracy |

| Rusinovich et al.10 | Retrospective multicenter cohort | Intraoperative flow | MobileNetV2, TensorFlow.js | Correlation coefficient: 0.7 vs 0.14 for IM GLASS | 95% validation accuracy, 93% test accuracy |

| Panuccio et al.2 | Prospective cohort | Preoperative mapping, Intraoperative flow | Automated fusion imaging | 92% usability, 0mm median registration error | Automated success: 56%; manual assistance required: 80% of cases; median registration error 0mm; applicability 92% |

| Mavioso et al.3 | Observational pilot | Preoperative mapping | Vessel centreline extraction | ∼2h/case reduction | Better for vessels>1.5mm (P=2e−3), worse for <1.5mm (P=6e−4) |

| Bailey et al.7 | Retrospective cohort | Preoperative mapping, Intraoperative flow, Anastomosis | Cloud-based fusion imaging | Contrast: −21% (105–83mL, P=.005); Operative time: −9% (204.4–186min, P=.278) | Not reported |

| Li et al.8 | Model development | Anastomosis assistance | Deep learning | Not reported | IoU=0.43±0.29; F1=0.53±0.32; Accuracy=0.97±0.002 |

| Eves et al.4 | Scoping review | Preoperative mapping, Anastomosis | Augmented reality | Qualitative improvements only | Not reported |

AI/CV=artificial intelligence/computer vision; AUROC=area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; IoU=intersection over union; EVAR=endovascular aneurysm repair; ARVA=augmented reality vessel analysis; RCT=randomized controlled trial; 2D/3D=two-dimensional/three-dimensional. This table summarizes study design, application domain, CV/AI techniques, key quantitative outcomes, performance metrics, and reported limitations for each included study. Data were extracted from full-text articles retrieved through the defined search strategy.

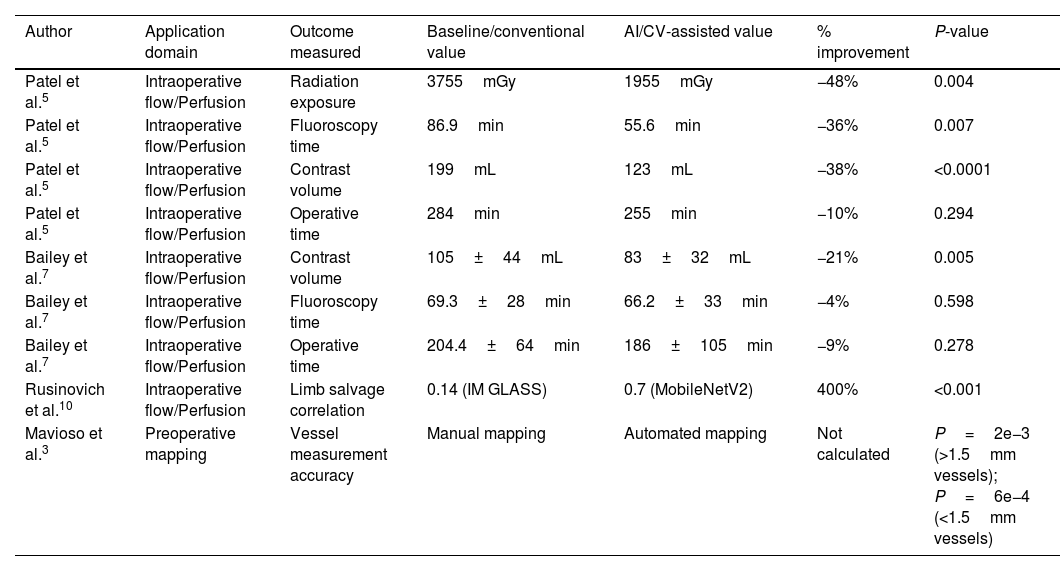

Comparative outcomes of AI/CV-assisted versus conventional methods in vascular surgery.

| Author | Application domain | Outcome measured | Baseline/conventional value | AI/CV-assisted value | % improvement | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patel et al.5 | Intraoperative flow/Perfusion | Radiation exposure | 3755mGy | 1955mGy | −48% | 0.004 |

| Patel et al.5 | Intraoperative flow/Perfusion | Fluoroscopy time | 86.9min | 55.6min | −36% | 0.007 |

| Patel et al.5 | Intraoperative flow/Perfusion | Contrast volume | 199mL | 123mL | −38% | <0.0001 |

| Patel et al.5 | Intraoperative flow/Perfusion | Operative time | 284min | 255min | −10% | 0.294 |

| Bailey et al.7 | Intraoperative flow/Perfusion | Contrast volume | 105±44mL | 83±32mL | −21% | 0.005 |

| Bailey et al.7 | Intraoperative flow/Perfusion | Fluoroscopy time | 69.3±28min | 66.2±33min | −4% | 0.598 |

| Bailey et al.7 | Intraoperative flow/Perfusion | Operative time | 204.4±64min | 186±105min | −9% | 0.278 |

| Rusinovich et al.10 | Intraoperative flow/Perfusion | Limb salvage correlation | 0.14 (IM GLASS) | 0.7 (MobileNetV2) | 400% | <0.001 |

| Mavioso et al.3 | Preoperative mapping | Vessel measurement accuracy | Manual mapping | Automated mapping | Not calculated | P=2e−3 (>1.5mm vessels); P=6e−4 (<1.5mm vessels) |

AI/CV=artificial intelligence/computer vision; EVAR=endovascular aneurysm repair. Values for AI/CV-assisted methods are compared with baseline/conventional approaches for each reported outcome. Percentage improvement and statistical significance (P-value) are provided when available. Outcomes include radiation exposure (mGy), fluoroscopy time (minutes), contrast volume (mL), operative time (minutes), and accuracy metrics. Data reflect results as reported in the included studies; no additional statistical analyses were performed.

A comprehensive search was performed in the Semantic Scholar corpus via the ELICIT platform, which indexes over 126 million academic papers, complemented by targeted searches in PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, and IEEE Xplore. The search was restricted to studies published in the last 5 years (up to [insert month/year]) in English or Spanish. The search query combined controlled vocabulary (MeSH) and free-text terms: “computer vision”, “artificial intelligence”, “vascular surgery”, “preoperative mapping”, “intraoperative flow assessment”, “perfusion assessment”, and “anastomosis verification”. Equivalent terms were adapted for the other databases. Reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews were also screened to identify additional eligible records.

Eligibility criteriaInclusion:

- •

Human studies in vascular surgery using computer vision/artificial intelligence for preoperative mapping or intraoperative flow/perfusion assessment.

- •

Original research (prospective, retrospective), systematic reviews, narrative reviews, technical notes, and clinically relevant conference proceedings.

- •

English or Spanish language.

- •

Published in the last five years.

Exclusion:

- •

Animal or purely in vitro studies without clinical translation.

- •

Reports lacking methodological detail on the AI/CV application.

- •

Case reports without technical validation.

- •

Purely technical or algorithm development papers without clinical evaluation.

- •

Studies without full-text availability or with insufficient methodological detail.

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts for relevance, followed by full-text assessment. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. For each included study, the following variables were extracted:

- •

Authors, year, country.

- •

Study design and sample size.

- •

Application domain (preoperative, intraoperative).

- •

Technical specifications (imaging modality, acquisition parameters, AI/CV model, dataset size, training/validation method, performance metrics).

- •

Clinical outcomes (accuracy, sensitivity/specificity, time saved, radiation/contrast reduction, complication rates). Data extraction.

- •

CV/AI technique used (e.g., deep learning architecture, fusion imaging, augmented reality).

- •

Model performance metrics (validation/test accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, AUC, IoU, F1 score).

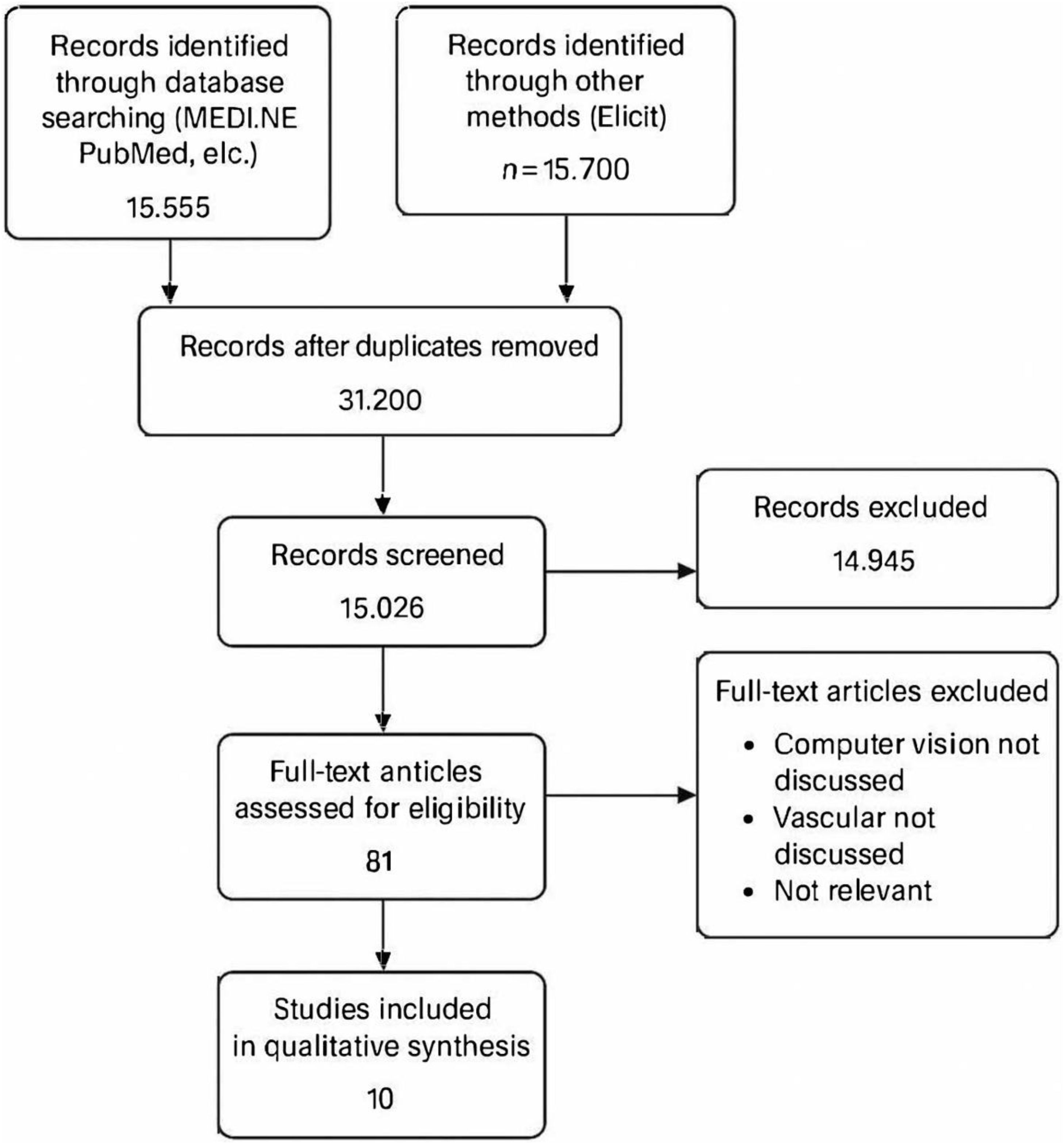

A comprehensive search was performed across PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, and complemented with Elicit, which indexes over 126 million academic papers. The combined search initially retrieved 31,200 records. After applying inclusion criteria (English/Spanish language, last 5 years, human studies evaluating computer vision/AI in vascular surgery), 15,026 records were screened. Following title/abstract screening and full-text evaluation, 81 records were assessed for eligibility. After removal duplicates between database and Elicit searches, 10 studies were included in the final qualitative synthesis, illustrated in Fig. 1, PRISMA flow diagram.

Screening was independently performed by two reviewers, with discrepancies resolved by consensus. Exclusion criteria comprised animal/in vitro studies, purely technical algorithm development without clinical evaluation, case reports lacking methodological validation, and papers without accessible full text.

Synthesis of evidenceGiven the heterogeneity in interventions, outcome measures, and study designs, a qualitative synthesis was conducted. Studies were grouped by application domain, and findings were narratively summarized to highlight technological advances, clinical outcomes, and evidence gaps. Quantitative data were presented in summary tables (Table 1) and, where possible, aggregated as medians or ranges without additional statistical pooling. We synthesized the comparative results between AI/CV-assisted and conventional approaches in vascular surgery (Table 2). Across most comparisons, AI/CV was associated with improvements in operative efficiency (∼5–10% reductions in operative time), lower resource utilization (reductions in radiation exposure up to 48% and contrast use up to 38%), and high diagnostic performance (median AUROC ∼0.85–0.90), without a clear increase in perioperative complications. However, effect sizes were heterogeneous and derived mostly from single-center retrospective series with limited external validation, so the overall certainty of the evidence is moderate-to-low. The table details, by study and technique, the primary outcomes and performance metrics.3,5,7,10

Main body- 1.

Preoperative applications

Artificial intelligence (AI) and computer vision (CV) are increasingly explored for preoperative vascular mapping, aiming to enhance precision and efficiency beyond conventional subjective evaluations.1,3 These applications primarily focus on diagnosis, image segmentation, and vessel planning.1 For perforator mapping in microsurgical reconstruction, a semi-automatic methodology utilizing CV techniques has been evaluated to reduce mapping time and subjectivity.9 This approach combines vessel centerline extraction and local characterization algorithms to identify perforators from computed tomography angiography (CTA) scans.3 Quantitative outcomes demonstrated that while software caliber estimates were worse for vessels smaller than 1.5mm (P=6e−4), they were better for those larger than 1.5mm (P=2e−3) when compared to intraoperative measurements.9 Although a statistically significant vertical localization error (P=0.02) was observed (average absolute error 3.2±2.4mm), this was deemed clinically irrelevant due to its small magnitude.3 A key strength was the reduction in analysis time by approximately 2h per case.3 However, a limitation is that this semi-automatic method still requires user input and relies on the availability of expert-annotated datasets for future machine learning advancements.3

In the context of aortic diameter assessment and planning for complex endovascular aortic repair (EVAR), deep learning models, specifically Augmented Reality Vessel Analysis, have shown promise.9 This technology achieved 89% accuracy in aortic wall identification with a median measurement error of 2.4mm pre-analysis and 1.6mm post-analysis.9 For broader vessel planning and diagnostic accuracy, AI-assisted fusion imaging has demonstrated high performance. A systematic review found that AI models used for diagnosis and segmentation in vascular surgery had a median Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) of 0.88 (range 0.61–1.00), with 79.5% of studies reporting an AUROC≥0.80.1 This suggests excellent predictive ability within the research setting.1 Fully automated fusion imaging engines have also been assessed for preoperative planning in endovascular aortic repair, creating mesh models of the aorta from preinterventional CT scans.2 One prototype was found applicable in 92% of cases, demonstrating a median automatic registration error of 0mm (interquartile range, 0–5mm).2 While promising for simplifying workflow, full automation was only achieved in 12% of cases, with manual intervention required in 80% (e.g., for centerline correction in 48% or mesh model fitting issues in 44%).2 The presence of vessel kinking was identified as a factor hindering complete mesh model generation.2

Comparing these findings, while semi-automatic and automated tools show significant time-saving potential and high diagnostic accuracy in specific tasks like perforator mapping and aortic assessment,3,9 the variability in software accuracy depending on vessel size9 and the frequent need for manual corrections2 highlight current limitations in achieving fully autonomous preoperative planning across all anatomical complexities. Nevertheless, the general trend indicates improved diagnostic capabilities and potential for reduced subjectivity in planning.2–4

- 2.

Intraoperative applications

The integration of AI and CV tools for intraoperative guidance and flow/perfusion assessment is driven by the need to enhance patient and operator safety by reducing radiation exposure and contrast agent use, particularly in complex vascular procedures.5–7 These technologies aim to provide real-time, augmented visualization that improves procedural efficiency and accuracy. AI-assisted surgical overlay/intelligent maps are a key application for complex aneurysm repair, including pararenal, juxtarenal, and thoracoabdominal aneurysms, as well as fenestrated EVAR.5–7 These cloud-based platforms generate patient-specific 3D maps from preoperative CT scans, which are then superimposed with real-time fluoroscopic Images 6. This allows for easier identification, cannulation, and stent placement of visceral vessels, especially with real-time adjustments for anatomical deformation caused by patient posture or device insertion.5 Quantitative outcomes reported by Patel et al.5 for complex aneurysm repair using AI-assisted maps demonstrated:

- •

Radiation exposure reduced by 48% (from 3755mGy to 1955mGy; P=.004).5

- •

Fluoroscopy time reduced by 36% (from 86.9min to 55.6min; P=.007).5

- •

Contrast use reduced by 38% (from 199mL to 123mL; P<.0001).5

- •

Operative time decreased by 10% (from 284min to 255min), though this was not statistically significant (P=.294) in univariate analysis.5 However, in adjusted linear regression models, Patel et al. (2023) reported a statistically significant decrease in operating room time, contrast used, radiation exposure, and fluoroscopy time for the AI group.

Similar benefits were reported for fenestrated EVAR using cloud-based fusion imaging (Cydar EV Intelligent Maps).7 This study observed:

- •

Statistically significant decrease in iodinated contrast volume by 21%** (from 104.7mL to 83.8mL; P=.005).7

- •

Statistically significant decrease in patient radiation exposure (dose-area product) by 40% (from 1,049,841mGy/cm2 to 630,990mGy/cm2; P<.001).7

- •

Non-significant trends toward shorter fluoroscopy times (4% reduction) and operative times (9% reduction).7

Crucially, no significant difference in 30-day postoperative complications, endoleak, reintervention, or all-cause mortality was found with the use of AI technology in these studies, suggesting improved safety metrics without increasing adverse events.5–7 This supports the notion that AI-assisted guidance can streamline workflow without compromising patient safety.8

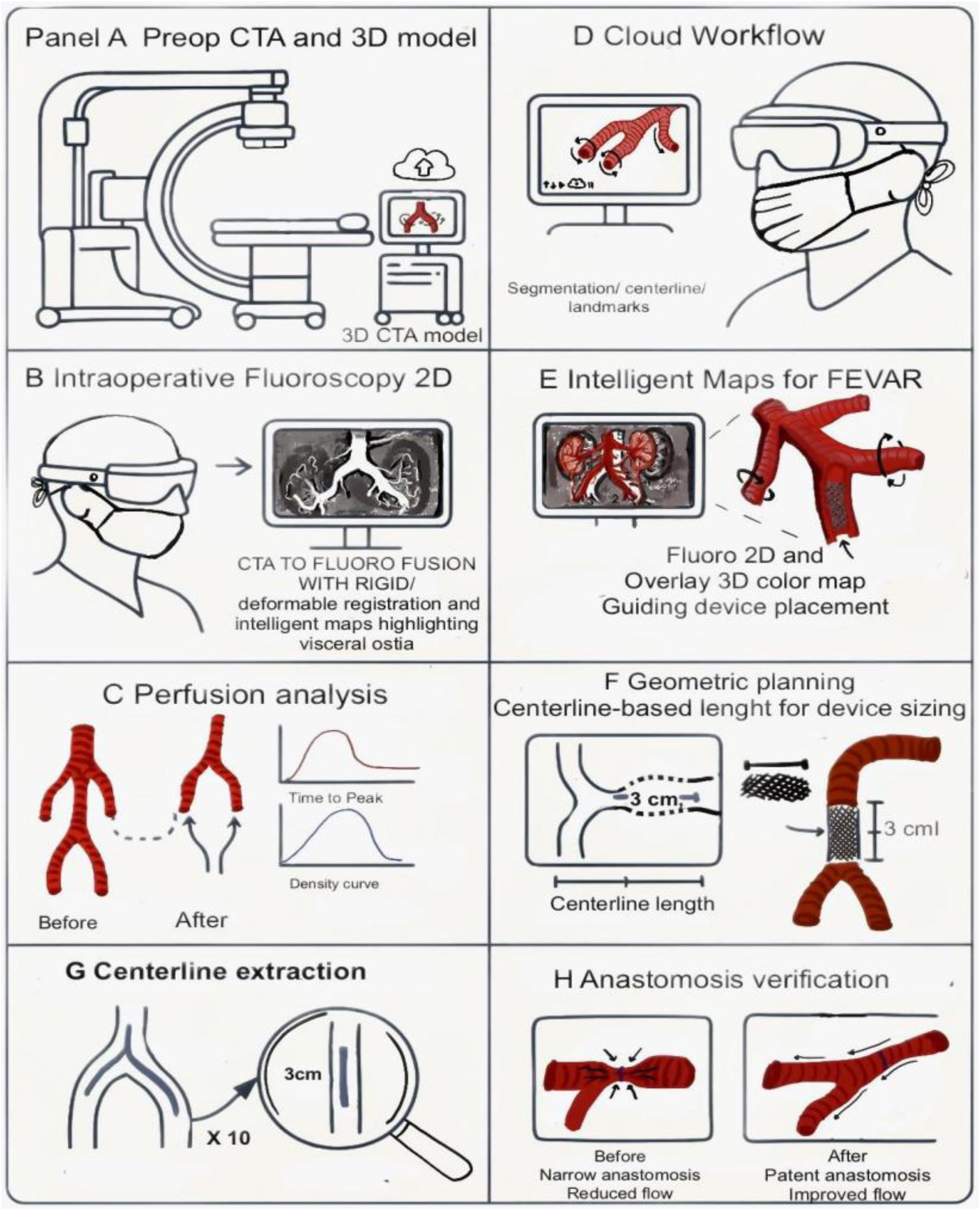

Another intraoperative application involves automated fusion imaging engines that match preinterventional CT with intraoperative fluoroscopic angiography.2 This 2D/3D registration technique, utilizing both vessel and bone landmarks, was found to have a median error of 0mm and required minimal additional radiation exposure (0.1–0.6% of the total procedure).2 The technology aims to simplify workflow and reduce user-related errors, being applicable in most cases (92%), though it still frequently required manual assistance (80%) for full functionality.2 For limb salvage prediction in peripheral arterial disease, a deep learning model (MobileNetV2 with transfer learning) achieved 95% validation accuracy and 93% test accuracy, significantly outperforming traditional methods.10 This highlights the potential of AI in real-time outcome prediction during complex interventions. AI-assisted fusion and intelligent maps superimpose a preoperative CTA model onto live fluoroscopy, with rigid/deformable registration for anatomical changes. Fig. 2 depicts the CTA-to-fluoro fusion workflow and intelligent overlays highlighting visceral ostia and device guidance.

2D/3D fusion and intelligent maps for fEVAR: workflow and examples. (A) Preoperative CTA segmentation and 3D model. (B) Live intraoperative fluoroscopy (2D). (C) Perfusion analysis before/after with time–density curves. (D) Cloud workflow for segmentation, centerline, and landmarks. (E) Intelligent overlay highlighting visceral ostia and guiding device placement. (F) Geometric planning: centerline-based length (L) and landing-zone height (H). (G) Centerline extraction with local diameter (D). (H) Anastomosis verification (patency and flow). Abbreviations: CTA, computed tomographic angiography; 2D/3D, two-dimensional/three-dimensional; TTP, time-to-peak; EVAR, endovascular aneurysm repair; fEVAR, fenestrated endovascular aneurysm repair. Figure designed and illustrated by the authors in Procreate.

Overall, the reported benefits across studies consistently include significant reductions in radiation exposure and contrast media use, alongside non-significant (or statistically significant in adjusted models) improvements in operative times.5–7 The ability of AI tools to provide real-time guidance and adjust for anatomical deformations is a significant strength,6,7 enhancing procedural efficiency and safety without an increase in complication rates.6 However, the persistent need for manual intervention in some automated systems2 and the variability in statistical significance for operative time reduction indicate areas for continued development and more robust evidence.

- 3.

Evidence gaps and barriers

Despite the promising advancements of AI and CV in vascular surgery, their widespread clinical translation is hindered by significant evidence gaps and methodological shortcomings prevalent in the current literature.1

Heterogeneity in Study Designs and High Risk of Bias: A major barrier is the overwhelmingly high risk of bias in nearly all studies (94.8% of 212 reviewed).1,5,10 This is primarily attributed to inadequate reporting of missing data, lack of model calibration, and failure to account for overfitting.1 The predominant study design is retrospective and single-center, with only a handful of prospectively tested models (five studies) and a complete absence of randomized controlled trials.1,5,10 This inherent lack of high-level evidence limits the ability to establish causality and robustly assess clinical impact.

Lack of external validation: A critical limitation for generalizability is the conspicuous absence of external validation of AI/CV models, performed in less than 5% of studies.1,5,10 This means that models developed on specific datasets may not perform reliably across different patient populations, institutions, or imaging equipment, severely limiting their applicability in diverse clinical settings.1 The varying accuracy of software by vessel size3 and issues with image registration accuracy due to anatomical deformation2,7 further underscore the need for rigorous external validation across diverse anatomical variations and procedural scenarios.

Limited and fragmented datasets: Many studies fail to fully leverage the potential of AI by relying on single data modalities (e.g., imaging alone or structured clinical data alone), instead of multimodal data fusion.2,5,10 There is also often insufficient detail on demographic reporting and inclusion/exclusion criteria (less than 20% of studies), raising concerns about potential biases and hindering the understanding of model applicability to diverse patient cohorts.1 The common use of retrospective, single-center data further limits external validity.9,10

Variability in Software Accuracy and Technical Limitations: While high technical accuracy is reported for specific tasks like segmentation and prediction,9,10 automated tools may still require manual correction,2,9 suggesting that hybrid workflows are still necessary. Challenges with image registration accuracy due to anatomical deformation during procedures8 and the need for robust deformable registration algorithms or real-time 3D scanners persist.8 The reliance on vertebral body identification for image linking can be a limitation in cases of severe osteoporosis or spinal hardware.6

Poor adherence to reporting standards and model transparency: The adherence to standardized reporting guidelines, such as TRIPOD and PROBAST, is suboptimal (41.4%).1,9,10 This results in a lack of transparency regarding methodological details and a general absence of shared source codes, impeding reproducibility and hindering further development and clinical adoption.1,7–10 Without adequate reporting on how AI models can be used by readers (less than one in four studies), their clinical applicability remains limited.1 These pervasive methodological limitations, coupled with fragmented reporting, indicate that despite the high predictive potential demonstrated in research settings, the field is still in a nascent stage of robust clinical validation.1

- 4.

Future directions

To bridge the identified evidence gaps and accelerate the safe and effective integration of AI and CV into vascular surgical practice, several research priorities are crucial. Development of multicenter, expert-annotated datasets: The current reliance on retrospective, single-center data with limited demographic details severely restricts external validity and generalizability.1,5,9,10 Future research must prioritize the creation of large, multicenter, prospective datasets that incorporate diverse patient populations, anatomical variations, and disease pathologies.1,10 These datasets should be expert-annotated to ensure high-quality ground truth for model training and validation. Leveraging existing registries like the Vascular Quality Initiative could facilitate this.1 Furthermore, future studies should consider training AI models on multiple data types, including structured clinical data, laboratory results, and unstructured imaging data and clinical notes, to potentially increase predictive power, as suggested by successful examples.1

Prospective and externally validated trials: The most significant evidence gap is the absence of randomized controlled trials and the paucity of external validation.1,9,10 Future studies must move beyond retrospective analyses to conduct prospective trials assessing the impact of AI/CV tools on clinically relevant outcomes, such as complication rates, long-term patient survival, and cost-effectiveness.1,4 Rigorous external validation across different clinical settings, patient cohorts, and imaging systems is paramount to demonstrate generalizability and foster clinical trust.1 Exemplary studies that have successfully performed external validation should serve as a guide for future methodological rigor.1

Integration into real-time operative platforms and addressing technical limitations: While current AI tools offer benefits like real-time guidance and reduced radiation,6 challenges such as anatomical deformation during procedures and the need for manual corrections persist.2–4 Future efforts should focus on developing more robust deformable registration algorithms and integrating real-time 3D scanning capabilities to maintain accuracy despite anatomical changes.4 Improvements in hardware, such as lighter and more capable head-mounted displays, are also needed to enhance user comfort and expand application scope.4 The aim is to achieve fully automated tools that are seamless and minimize user intervention, eventually shortening analysis time to seconds.9

Adherence to standardized reporting (e.g., TRIPOD) and risk-of-bias tools (e.g., PROBAST) should be prioritized to improve transparency, reproducibility, and clinical applicability.1 Sharing de-identified data and code will facilitate external validation and multicenter replication.1

None of the included studies reported direct acquisition or maintenance costs for AI/CV platforms; however, they consistently documented resource-use reductions that have clear economic implications. In complex aortic repair, AI-assisted intelligent maps and cloud-based fusion imaging were associated with lower radiation exposure (up to −48%) and shorter fluoroscopy time (−36%), as well as reduced iodinated contrast use (up to −38%) and non-significant trends toward shorter operative time (≈4–10%). These efficiency gains suggest potential downstream savings in consumables, imaging time, and staff exposure, even though formal cost-effectiveness analyses were not reported in the included literature. Additionally, automated 2D/3D fusion engines added minimal extra radiation (≈0.1–0.6% of total procedural dose), supporting their safety and operational efficiency.2,5,7

Professional/organizational cost of adoption. The literature consistently shows that current AI/CV tools still require human expertise and additional workflow steps, which translate into professional/organizational cost rather than direct monetary figures. For example, automated 2D/3D fusion engines often need manual corrections (centerline adjustment, mesh fitting) in a large share of cases despite low registration error, indicating that trained operators must remain in the loop and allocate time for verification.2 Intraoperative use can also be affected by anatomical deformation, which demands familiarity with deformable registration concepts and vigilant intraoperative QA to maintain accuracy.4,8 More broadly, the predominance of single-center, retrospective designs and scarce external validation reported across vascular AI/CV studies implies that local teams will need to invest professional effort in site-specific verification, protocol development, and staff training before routine use.1 Finally, suboptimal reporting/transparency noted in the field (e.g., incomplete method details, limited sharing of code/data) adds a burden of clinical governance (documentation, reproducibility checks, compliance with reporting standards) when integrating these tools into practice.1 These tools complement—not replace—clinicians: multidisciplinary teams (surgeons, interventional radiologists, anesthesiologists) work alongside clinical/biomedical engineering and IT support; medical decision-making remains the responsibility of the clinical team.2,4

Implementation settings. Preoperative segmentation and 2D/3D fusion preparation naturally align with Radiology services. Hybrid operating rooms are the primary setting for intraoperative overlays and fusion guidance during EVAR/fEVAR. Outpatient planning clinics benefit from semi-automatic mapping and centerline-based measurements to streamline device sizing and case discussion.1–4

ConclusionsAI and computer vision applications in vascular surgery demonstrate measurable benefits in preoperative planning and intraoperative guidance, including reductions in radiation exposure, contrast use, and procedure time, alongside high diagnostic accuracy in selected tasks. However, these promising results are predominantly derived from retrospective, single-center studies with limited external validation and heterogeneous methodologies. The field remains in an early stage of clinical translation, and widespread adoption will depend on the development of multicenter, expert-annotated datasets, rigorous prospective validation, integration into real-time operative platforms, and adherence to standardized reporting. Addressing these priorities will be essential to move from promising prototypes to clinically validated, widely adopted AI/CV tools that improve patient outcomes and surgical efficiency.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Ethical considerationsThis article is a narrative review and did not involve direct research with human participants or animals; therefore, institutional review board approval and informed consent were not required. All data were extracted from previously published studies that had undergone their respective ethical review processes. No patient-level or identifiable data were collected, analyzed, or shared. Literature retrieval was complemented with Elicit (an AI-assisted search tool), used solely to broaden the search space; all records identified via Elicit were independently screened and verified by the authors for relevance, accuracy, and quality prior to inclusion. This statement is provided in addition to the journal's standard Ethical Disclosures document.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.