Controlling bacterial and viral growth in surfaces is crucial in combating infectious diseases. Therefore, the development of glazes with bactericidal and viricidal effects for ceramic tiles appears highly advantageous. These glazes would facilitate personal and public hygiene due to the widespread use of ceramic tiles in the construction industry and urban planning (homes, hospitals, etc.).

Biocidal glazes have been developed from a silver containing frit. This frit has been formulated by substitution of a fraction of alkaline oxides for silver and obtained by melting and quenching the melt. Its composition allows the incorporation of the silver into the vitreous network. Silver-containing glazes for wall tiles and floor tiles had been obtained from the frit, but a fraction of the silver was present as metallic silver particles. The inhibitor effect of the glazes against bacteria (Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus) and virus (TEGV) was verified according to ISO 22196:2011/JIS Z 2081/2010 and ISO 21702:2019 standards respectively.

The production of biocidal tiles was successfully scaled up while preserving their biocidal efficacy (mean results of 99.9%, 99.7% and 94.6% against E. coli, S. aureus and TEGV respectively). However, variability increased due to the lower reproducibility of the thermal cycles in industrial roller kilns. In addition, the silver content in the surface of the glaze was maintained after accelerated aging tests, pointing to a good durability of these properties.

El control del crecimiento vírico y bacteriano sobre superficies es crucial para combatir enfermedades infecciosas. Por tanto, el desarrollo de vidriados cerámicos con propiedades viricidas y bactericidas resulta de especial interés. Dichos vidriados facilitarían la higiene personal y pública dado el amplio uso de las baldosas cerámicas en la construcción (viviendas, hospitales, etc.).

Se han desarrollado vidriados biocidas a partir de una frita con plata, formulada sustituyendo una fracción de los alcalinos por plata. La frita se ha sintetizado por fusión y enfriamiento súbito del fundido, empleándose para obtener vidriados en baldosas de pavimento y revestimiento, si bien una fracción de la plata se hallaba en forma de partículas metálicas. El efecto inhibidor de los vidriados frente al crecimiento de bacterias (E. coli y S. aureus) y virus (TEGV) se ha evaluado según las normas ISO 22196:2011/JIS Z 2081/2010 y ISO 21702:2019, respectivamente.

La obtención de las baldosas cerámicas se escaló a una planta industrial manteniendo la actividad biocida (valores medios de 99.9%, 99.7% and 94.6% frente a E. coli,S. aureus y TEGV respectivamente). Sin embargo, la variabilidad aumentó debido a la menor reproducibilidad de los ciclos térmicos en los hornos industriales de rodillos. Además, se verificó que el contenido en plata en la superficie del vidriado se mantenía tras ensayos acelerados de envejecimiento, lo que implica una buena durabilidad de dicho efecto.

Bacteria and viruses rank among the most significant global health challenges today [1]. These microscopic pathogens pose a severe threat to human health, with some even being potentially lethal [1]. While bacteria are unicellular organisms capable of independent growth and reproduction, viruses are much simpler and require host cells to replicate their genetic material [1].

The recent COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease-2019) pandemic, which emerged in China in December 2019, has had an unprecedented global impact. Caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus (hereafter referred to as coronavirus), this pandemic has reached every country, resulting in over 775 million reported cases of SARS-CoV-2 respiratory illness worldwide [2]. Consequently, public awareness has grown significantly regarding infection spread, hygiene, cleanliness [3–5], and how we conduct our daily lives, including work and social interactions.

The rapid spread of COVID-19, caused by the airborne or surface-borne transmission of the virus through respiratory droplets, exemplifies the dangers of such pathogens [3]. To combat these threats, global health organizations emphasize frequent disinfection of high-touch surfaces within buildings [1,6,7]. While cleaning agents like ethanol, bleach, hydrogen peroxide, and specialized disinfectants are effective [1,6,7], frequent use can be impractical due to logistical difficulties, material wear, or resource limitations [3].

Ceramic materials, including tiles, toilets, sinks, windows, and countertops, are prevalent in both private and public spaces (homes, hospitals, schools, factories) [6]. In fact, global ceramic tile production reached a staggering 16,762 million square meters in 2022 [8], highlighting their widespread use in construction

Ceramic tiles are non-metallic, inorganic materials formed through cold-pressing and shaped before acquiring their final properties through high-temperature firing (above 1100°C) [9]. They are widely used as floor and wall coverings, as well as for other building elements [9]. The production process involves a mixture of clays, frits, and other raw materials like feldspars, quartz, and inorganic oxides [9]. Tile surfaces are often glazed to create a smooth, aesthetically pleasing, and highly functional surface. Decorative techniques such as inkjet technology further enhance their visual appeal [10]. While ceramic tiles offer several advantages, such as high mechanical and wear resistance, and ease of cleaning with chemical agents due to their inherent chemical resistance [10], they also have some drawbacks. These include significant weight, particularly in larger formats, vulnerability to impacts, higher cost compared to some alternative materials, and difficulty of replacing once installed. It is important to note that despite their ease of cleaning, ceramic tiles themselves do not possess inherent biocidal activity. Consequently, in warm and humid environments, pathogens can readily grow and multiply on tile surfaces [1,6].

The ceramic industry continually seeks to enhance the appeal, aesthetics, and technical performance of traditional tiles by exploring novel glaze functionalities. These advancements include antibacterial [1,11–15], anti-pollutant, self-cleaning [14,16,17], moisture regulation [18], electrical [19], and thermal insulation properties [20–22]. In terms of antimicrobial functionality, research has focused on the bactericidal capacity of the glaze layer [16,23–25]. This is achieved either by applying an antibacterial coating to the finished tile surface or by incorporating the antibacterial agent directly into the glaze before firing. Several commercially available products with proven antibacterial treatments demonstrate the industry's commitment to creating hygienic environments [11–13]. However, conclusive evidence of viricidal efficacy remains elusive, both in research and commercially available products [1,2,6,23,26].

Various chemical agents, such as silver and copper nanoparticles, Ag+ or Cu+ cations, and oxides like Ag2O, TiO2, and ZnO, are known to exhibit varying degrees of antimicrobial effectiveness [1,2,6,23,26]. Reinosa et al. [1] provide a comprehensive overview of the latest solutions and mechanisms employed in the development of antimicrobial tiles. These mechanisms can be broadly categorized as utilizing nanoparticles, ions, photocatalytic effects, or physicochemical effects (temperature, roughness).

In the field of ceramics, silver and titanium compounds are popular choices for their antibacterial properties. Silver is a potent biocide, and its effectiveness stems from the release of silver ions (Ag+). Silver has been incorporated into ceramic surfaces by an ion-exchange method after firing the tile [27], but the biocide activity was measured qualitatively, not by a standardized method. This ion-exchange method is expensive and requires a more complex process to obtain the biocidal tile. A simpler option is the incorporation of silver into the glaze composition through conveniently formulated frits. The use of titanium dioxide (TiO2) requires a different approach. Due to its photocatalytic properties, only the anatase phase of TiO2 is effective. Unfortunately, this phase transforms into rutile at lower temperatures than the firing tiles ones (around 900°C) [15]. Consequently, TiO2 coatings must be applied after the firing of the tile and fixed at a moderate temperature (600–850°C). This additional thermal treatment lengthens the production process.

On the other hand, incorporating either silver or titanium compounds into ceramic glazes presents a challenge. These additions can alter the final properties of the glaze, potentially introducing undesirable colours and increasing production costs. Therefore, significant research is still needed to optimize the balance between maximizing the biocidal effect, minimizing cost and production drawbacks, and ultimately transferring these advancements to the development of viricidal glazes.

This article focuses on conferring biocidal activity to ceramic wall and floor tiles doping with silver the glazed surface through silver-containing frits, without modifying the standard tile processing. The research aims to achieve the following advancements: (i) develop practical biocidal frit suitable for ceramic tile production, (ii) verify the biocidal functionality (killing both bacteria and viruses) of the glazed surfaces, (iii) scale-up the process to industrial level.

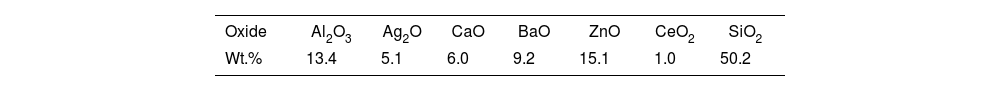

Material and methodsThe biocidal frit (reference F1) was prepared from a mixture of a commercial frit for transparent glazes, silver nitrate and other ceramic raw materials, including kaolinite and zinc oxide. After various experiments substituting a fraction of alkaline oxides by silver, a composition was obtained which represents a compromise between the silver content of the frit and the similarity between the appearances after a thermal cycle for tiles of the glaze obtained from it with the one of a standard transparent frit (Table 1).

To synthesize the frit, the raw materials were weighed, mixed, and loaded into an alumina crucible. The crucible was then thermally treated in an electric furnace (BLF1800, Carbolite Furnaces, UK), at 1500°C with a soaking time of 30min and the melt was quenched by pouring it over water. Following quenching, the frit was characterized by field-emission environmental scanning electron microscope (FEG-ESEM, Quanta 200 FEG, FEI Company, USA) and EDX (Pathfinder UltraDry EDS detector, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) to detect non-melted particles and assess the amount of silver incorporated into the vitreous lattice.

The industrial trials were performed with frit F1 produced in a pilot-scale furnace in a frit factory (VERNIS S.L., Spain).

Preparation of biocidal glazesThe preparation process for the glazing slip from F1 frit was the same for both wall tiles and floor (porcelain stoneware) tiles. To obtain a stable slip 0.3wt.% sodium tripolyphosphate (Quimialmel, Spain) and an equal amount of carboxymethylcellulose (Optapix C21G, Zschimmer & Schwarz, Germany) were added. The water content was adjusted to obtain a density of 1.4gcm−3. Finally, the mixture was ball milled in alumina jars for 15min at 230rpm.

160g of slip by square meter was deposited by airless application onto the tile surfaces. After drying, the wall tile test pieces were fired in an electric laboratory furnace (Pirometrol S.A., Spain) at a maximum temperature of 1130°C with a 6-min soaking time. While floor tile ones were fired at 1200°C with a 2-min soaking time.

The industrial scale glazes were obtained from the F1 frit synthesized at pilot scale. The slips were prepared at pilot scale and the deposition condition over the tiles reproduced the ones at laboratory scale. The tiles were fired in industrial roller kilns. The wall tiles were fired at a maximum temperature of 1130°C with a thermal cycle of 38min, while the floor tiles were fired at a maximum temperature of 1200°C with a thermal cycle of 43min.

Characterisation of biocidal glazesThe microstructure of the obtained glazes was characterized using FEG-ESEM and the proportion of silver in the surface was measured by EDX.

The antibacterial properties of coatings were evaluated following the standard method ISO 22196:2011/JIS Z 2081/2010 for measuring antibacterial activity on plastics and other non-porous surfaces. This standard involves inoculating Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus bacteria (as models for Gram-negative and Gram-positive respectively) on previously cleaned surfaces to assess the inhibition of microbial growth and the bactericidal effects of the glazed surfaces. The efficiency of the glazed surface against bacteria is evaluated as a percentage and validated as antimicrobial if the percentage ≥99%.

The virucidal properties of the glazes were evaluated according to the standard method ISO 21702:2019, “Measurement of antiviral activity on plastics and other non-porous surfaces.” This standard allows the use of generic viruses (e.g., poliovirus), EN 14476 viruses (e.g., Vaccinia virus), and human coronavirus strain 229E. However, the results must be interpreted cautiously due to the varying sensitivities of different virus families to antivirals. In this study, transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) was chosen for evaluation on the different surfaces. It is important to note that a limitation of the ISO 21702 standard is the lack of a defined criterion for considering a product to be effective. Therefore, for this study, an efficacy of ≥90% was established as indicative of good virucidal performance.

Finally, the durability of the biocidal capacity of the glaze surfaces was estimated. Firstly, using the resistance to cracking test as a simulation of an accelerated aging of the glaze and to determine if silver could be extracted in humid environments. The samples were introduced into an autoclave and exposed to harsh conditions of temperature (160°C) and pressure (500kPa) in the presence of water vapor for a period of 4h, following the standard UNE-EN-ISO 10545-11:1997, “Determination of crack resistance of glazed tiles.” After drying the samples, EDX microanalysis was performed on their surfaces to evaluate the remaining silver proportion. Secondly, measuring the amount of acid-soluble silver on the surfaces. In this case, 25cm2 of the surface of the tile samples was placed in direct contact with 15mL of acetic acid solution for 24h, following the UNE-EN 12902 standard, “Determination of the acid soluble material.” Then, the amount of silver leached from the surface was measured using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES, spectrophotometer 5100, Agilent Technologies, USA). Considering that silver is the biocidal agent, if the extracted proportion of silver is very low, the remaining in the glaze could maintain the inhibitory behaviour of the glaze along time.

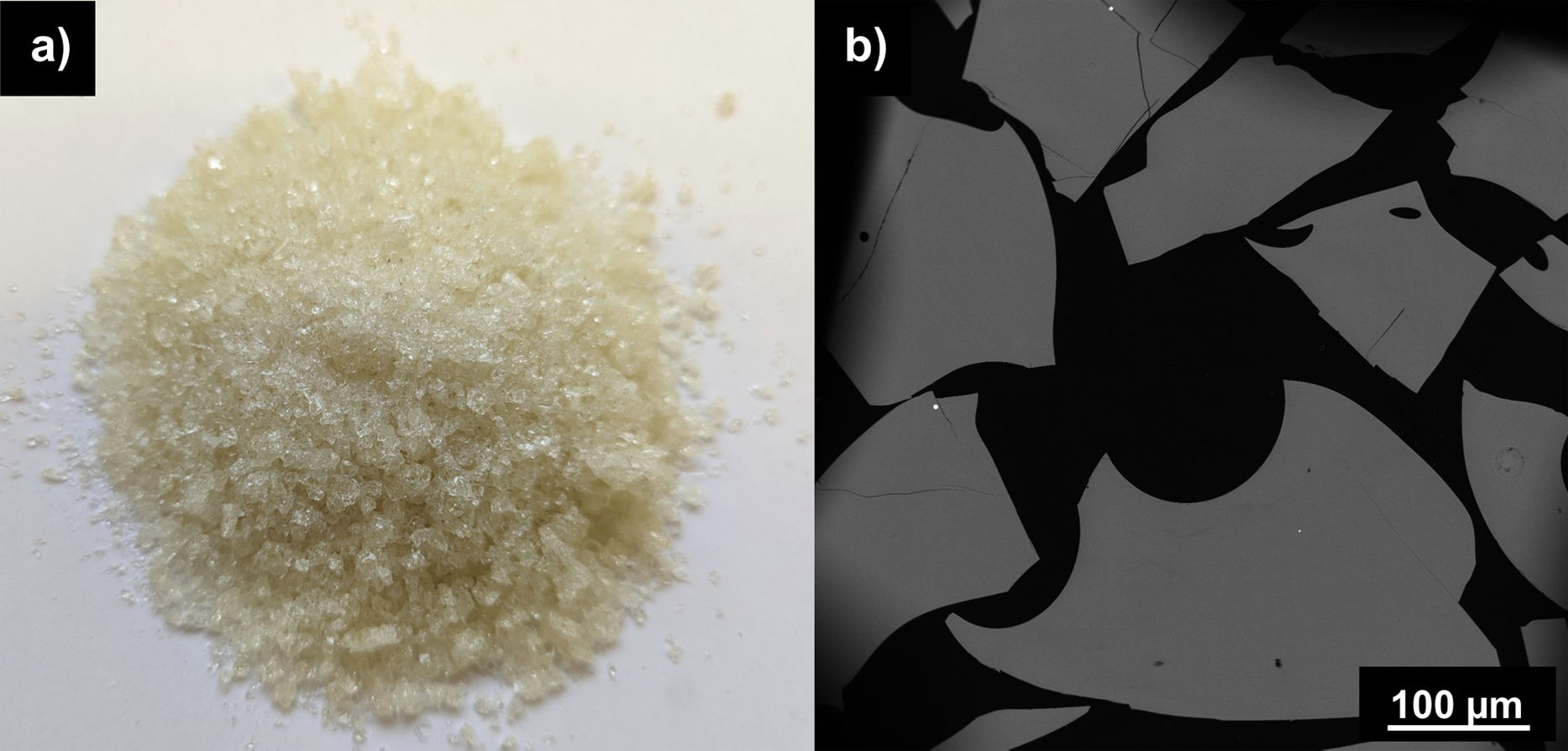

Results and discussionFrit synthesis and characterizationFrit F1 exhibited a homogeneous glassy appearance (Fig. 1a). However, SEM examination of polished sections (Fig. 1b) revealed a few isolated metallic silver particles less than 4μm in size within some frit grains. These particles likely resulted from either incomplete mixing of the raw materials or from an amount of silver locally exceeding its solubility in the vitreous network. EDX analysis of the homogeneous glass detected a 10% silver loss compared to the nominal content of the composition, which can correspond to the metallic particles. Despite this fact, frit F1 was considered a promising candidate to be used as a raw material for a biocidal glaze.

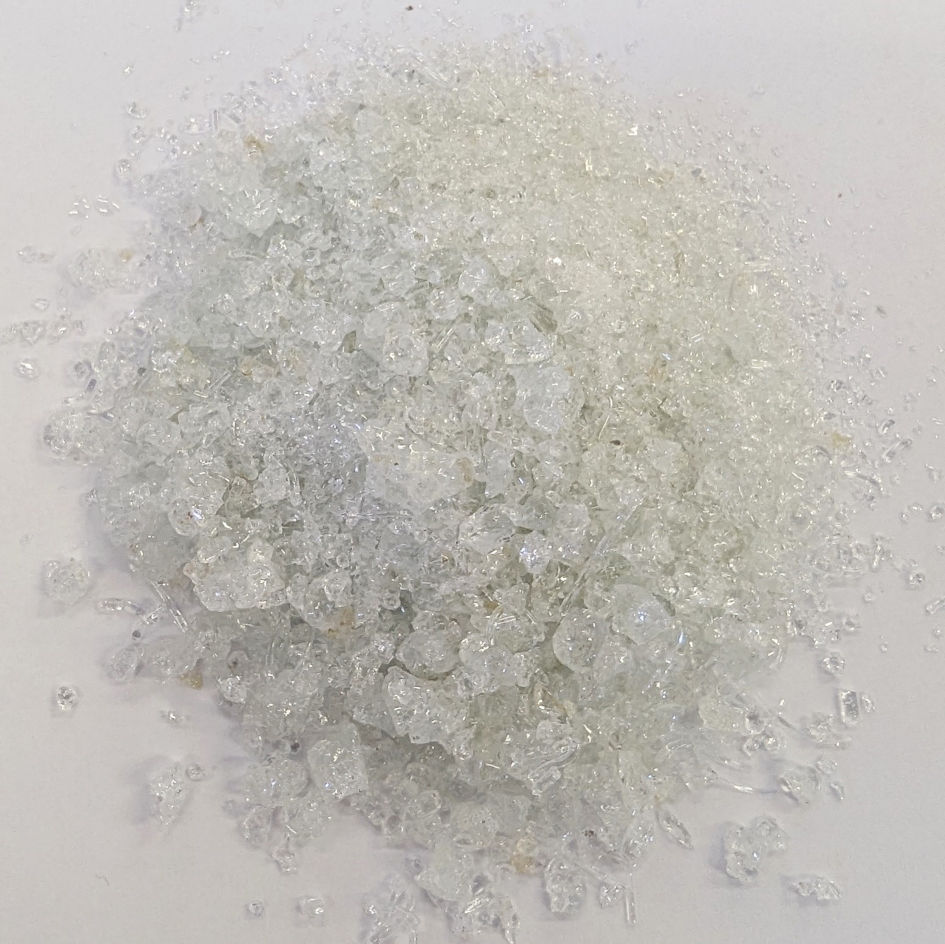

The pilot-scale frit F1 showed an uncoloured appearance with respect to the laboratory counterpart (Fig. 2), which could be related with the atmosphere during the melting of the frit, considering that the pilot scale furnace was heated by natural gas combustion, while the laboratory furnace was electrically heated. This fact can provoke a change in oxidation state of some impurities, as iron, present in the raw materials.

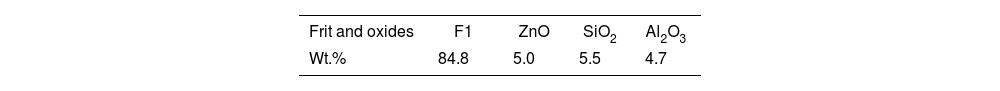

Laboratory-scale glazes synthesis and characterizationA matt type of ceramic glaze was developed for application on wall and floor tiles (reference E1, composition detailed in Table 2). A slip containing E1 was prepared and sprayed over the wall and floor tile supports and fired with their adequate thermal schedule.

The glazes exhibited whitish colour, without yellow shade, which points to a stable solution of silver in the glassy phase (Fig. 3a and b). Otherwise, the silver could have precipitated as silver nanoparticles that confer a characteristic yellow colour to the glaze [28]. However, some variations in surface roughness were observed, likely due to the firing cycle. The wall tile coating displayed a slightly rough texture (Fig. 3a), coherent with the lower maximum temperature of its firing cycle, while the floor tile coating had a smoother finish (Fig. 3b).

The microstructure of the coatings was typical of matt ceramic glazes, characterized by a surface covered by crystals and a reduced fraction of vitreous phase (Fig. 3c and d). Firing cycle differences resulted in larger crystals in the floor tile glaze (Fig. 3d). Additionally, the surfaces displayed randomly scattered metallic silver spheres of some microns of diameter (white spots in Fig. 3c and d), which probably come from the silver particles detected on the frit and were not the result of a nucleation and growth process, which probably would have modified the colour by the generation of some proportion of silver nanoparticles.

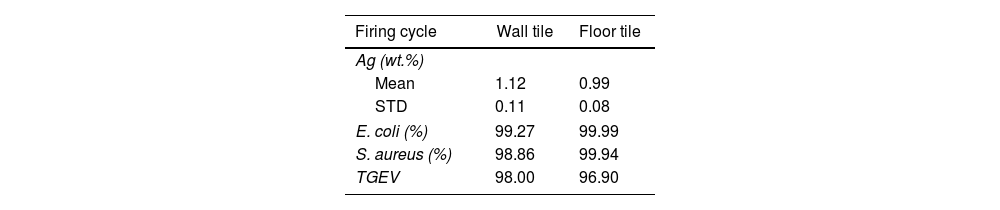

The biocidal results (bactericidal and virucidal efficacy) of the wall tile and floor tile glazes were summarized in Table 3, along with their surface silver content determined by EDX analysis. The thermal cycle affects the amount of residual silver on the glaze surface, as it slightly diminishes in the glaze fired at 1200°C, which could be interpreted considering that the grown crystals of bigger size partially cover the glassy phase that contains the silver. On the other hand, both glazes demonstrate very good bactericidal and virucidal efficacy. Wall tile glaze exhibits an efficacy of >98.8% against bacteria and >98.0% against viruses. While floor tile glaze shows superior efficacy against bacteria (99.9%), its virucidal efficacy is slightly lower (>96.9%). The antibacterial activity was like the one reported by Russo et al, but obtained adding silver nitrate to enamels for metallic surfaces fired a much lower temperature (850°C) [23]. Kim et al. obtained glazed ceramic tiles with similar antibacterial activity introducing metallic copper to the glaze [25], but this additive changes the colour of the surface. However, these works did not give data about the activity against viruses.

Industrial-scale wall tile glazes synthesis and characterizationThe pilot scale F1 frit was used to prepare E1 glaze, which was applied onto wall tiles. Three batches were prepared to assess reproducibility. The appearance of the samples was like the laboratory ones. The tiles maintain a white colour and matte surface and there are no significant changes in microstructure from one batch to another (Fig. 4).

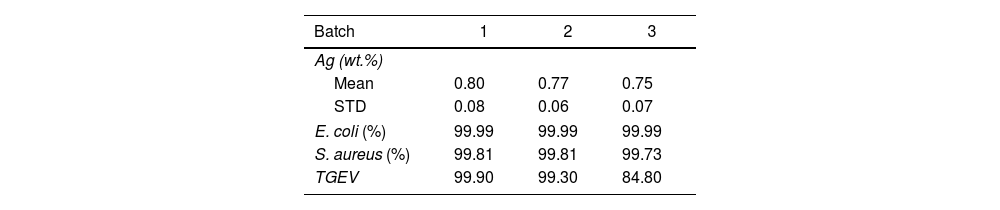

The industrial-scale wall tiles with E1 glaze possesses a lower content of silver with respect to the laboratory-scale ones, that could be a consequence of the differences in the thermal treatment. However, the biocidal activity against bacteria and viruses was maintained (Table 4). Activity against E. coli and S. aureus bacteria had average values of 99.99% and 99.78% respectively. Furthermore, the virucidal activity (TGEV) is also noteworthy, with a value of 94.69%. Therefore, these data indicate the transfer of the bioactive wall tiles from lab-scale to industrial scale is possible and the reproducibility of the process is good. However, the dispersion of the results of virucidal activity, points to a higher sensitivity of this function against the process variables.

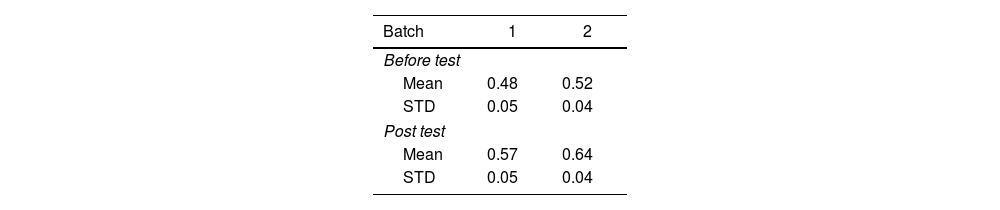

Some samples of industrial-scale wall tiles were subjected to a cracking test and the results were positive, as the samples did not present cracks in the glaze after the assay. However, there were differences in the microstructure before and after the cracking test (Fig. 5). A slight increase in the number of microcracks was observed, which can be attributed to the extreme temperature and pressure test conditions. The EDX analysis of the surface before and after the test showed no significant variations in the silver content despite the contact with high pressure water vapour (Table 5), meaning that silver is not extracted by water.

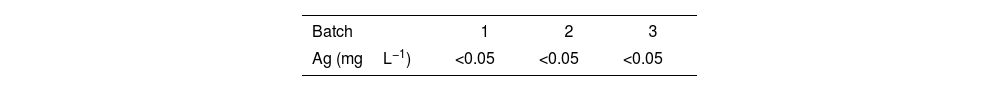

The acetic acid leaching tests showed that the amount of silver extracted from the glaze was under the detection limit of the assay (Table 6). Consequently, there is no evidence of silver solubility upon acid attack. However, the glaze has some interaction with the acid, because microporosity appears after acetic acid attack, as shows the changes in microstructure of the surface (Fig. 6).

Results had shown that silver is stable in the wall tile glaze obtained from frit F1, as it is not extracted by steam or acetic acid. Consequently, good durability of the biocidal activity for the wall tiles could be expected.

Industrial-scale floor tile glazes synthesis and characterizationE1 glaze was applied over floor tiles and, after firing, develops a white coating that is free of surface defects and exhibits a satin or slightly shiny appearance. This contrasts with the appearance of the tile surface when E1 glaze is used in wall tiles (Fig. 4) and is a consequence of the differences in firing schedules for floor and wall tiles. However, E1 glaze has a lower gloss than the standard of the market for a matte. Consequently, E1 glaze was modified by replacing 30wt.% of F1 frit with nepheline to reduce production costs and to achieve a shinier surface, resulting in the E2 glaze. This change in composition results in floor tile surfaces (E2) with an enhanced gloss due to its role as a flux at elevated temperatures, which increases the formation of the glassy phase.

The microstructure of the two glazes showed the differences in their composition (Fig. 7). The E1 glaze surface contains a higher proportion of crystals, while the E2 glaze surface showed a higher proportion of glassy areas.

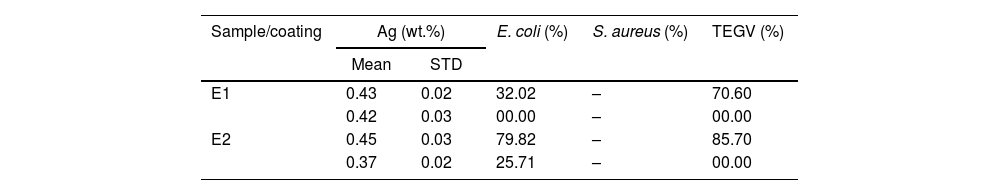

The silver content of different batches of the floor tiles glazed with E1 showed lower values than the laboratory ones (Table 7). These results must be attributed to the differences between the industrial and laboratory thermal cycles. Probably the industrial cycle includes more time at temperatures high enough to allow silver diffusion through the thickness of the glaze coating, and the amount remaining on the surface decreases. The silver content of E2 glazes is lower as it contains a reduced proportion of F1 frit.

The biocidal test results of the floor tiles glazed with E1 and E2 with E. coli and TGEV were low and inconsistent (Table 7), so tests with S. aureus were not performed. Furthermore, it can be observed that there is low reproducibility in the results obtained from coatings of different batches, pointing to other factors, in addition to the proportion of silver on glaze surface, that influences the biocidal activity in floor glazes.

The analysis of the relationship between the biocidal activity and silver content in the surface of the different tiles obtained along the study shows an approximate sigmoidal trend (Fig. 8), that point to a minimal content of 0.8% of silver in surface to obtain a good activity. Lower contents of silver generate surfaces with lower biocidal activity and more influenced by other factors, probably related with the local distribution of silver in the surface microstructure. However, this is an open question for future research to obtain a good biocidal activity with the minimal content of silver.

ConclusionsA silver-containing frit has been developed from an industrial tile frit which allow the silver to be incorporated into the glaze of the tiles to confer biocidal activity to the decorative tile surface. The production of biocidal glazes has been carried out using a standard procedure of ceramic tile manufacturing industry (wet milling, airless deposition and firing), and favours the scale up of the product. The frit allows the obtention of glazes for wall and floor tiles (firing temperatures of 1130°C and 1200°C respectively), with comparable appearance with industrial standards.

Biocidal tests on silver containing glazes determined that at laboratory scale excellent bactericidal and virucidal results are achieved in the two types of tiles. Thus, the surface coatings can inhibit the growth of E. coli and S. aureus bacteria with results of more than 98.80% and TEGV virus with a 96.00%.

The silver content of the surface seems to be the main factor responsible for the biocidal activity, because an approximately sigmoidal-type relationship has been found between the inhibition of microorganisms’ growth and the silver content on the glaze surface.

The scale up of the glazes to industrial scale showed that high biocidal activity was only reproduced for the wall tile, probably due to the lower firing temperature which allows the silver to remain on the surface. Thus, a feasible, effective and reproducible technology was established for biocidal wall tile with mean results of 99.9% and 99.7% on E. coli y S. aureus bacteria and 94.6% on TEGV. On floor tile, the silver content on the surface was not high enough to obtain a good biocidal effect. Further studies are still needed to adjust the glaze characteristics to maintain enough silver on surface after the industrial floor tile thermal cycle. In addition, the industrial roller kilns introduce higher variability in the results than the laboratory ones.

The simulation of the durability of biocidal activity in industrial wall tiles indicates that the silver content of the glaze is nearly maintained after steam and acid attacks. Consequently, a long permanence of the biocidal activity is expected. However, it should be noted that the microstructure of the coatings may be slightly modified along the tests.

CRediT authorship contribution statementVíctor Carnicer: Investigation, Visualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft.

Adriana Belda: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation.

Sergio Mestre: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

M.D. Palacios: Methodology, Investigation, Validation.

FundingThis research was funded by the SINVIR project (INNEST/2021/19) granted by AVI (Agencia Valenciana de la Innovació).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors thank Mª Carmen Segura (Vernis, S.A.) for the preparation and supply of industrial samples, and Rosa Pérez and Sales Ibiza (AIDIMME) for their technical assistance in the antibacterial and antivirucidal assays.