This study analyzes the structural and electrochemical properties of praseodymium- and gadolinium-doped ceria (CPGO) samples formed by the sintering reaction of Pr2NiO4+δ (PNO) and Ce0.9Gd0.1O2−δ (GDC). X-ray powder diffraction analysis confirmed a single-phase cubic CPGO structure as a primary phase. The cationic compositions were determined using energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) in a scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM), while core-loss electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS) was used to determine the valence of Ce and Pr. The compatibility between thermal expansion coefficients validated their integration with electrolytes at the typical Solid Oxide Cell (SOC) operation temperatures. Oxygen chemical diffusion and surface exchange coefficients were investigated using the electrical conductivity relaxation (ECR) method at intervals of partial oxygen pressures between 0.10 and 0.21atm and 600°C and 800°C. Finally, the samples were tested in symmetrical cells by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) between 700°C and 850°C. A polarization resistance of 0.17Ωcm2 at 850°C was obtained for CPGO air electrodes formed by sintering a mixture of 80% by weight of GDC and 20% by weight of PNO. These findings confirm that PNO–GDC mixtures forming CPGO oxides are excellent candidates for SOC applications.

En este estudio se analizan las propiedades estructurales y electroquímicas de composites formados por la reacción de sinterización de Pr2NiO4+δ (PNO) y Ce0.9Gd0.1O2-δ (GDC). Los refinamientos de Rietveld de los patrones de difracción de rayos X confirmaron una estructura cúbica monofásica de ceria dopada con praseodimio y gadolinio (CPGO) como fase primaria. Las composiciones catiónicas de CPGO se determinaron mediante espectroscopia de dispersión de energía (EDS) en un microscopio electrónico de transmisión de barrido (STEM), mientras que se utilizó espectroscopia de pérdida de energía de electrones (EELS) para determinar la valencia de Ce y Pr. La compatibilidad entre coeficientes de expansión térmica validó la integración de los electrodos con electrolitos a las temperaturas de operación típicas de las pilas de óxido sólido (SOC). Los coeficientes de difusión química de oxígeno y de intercambio superficial se determinaron mediante relajación de la conductividad eléctrica (ECR). Finalmente, se caracterizaron celdas simétricas mediante espectroscopia de impedancia electroquímica (EIS), obteniendo una baja resistencia de polarización de 0.17Ωcm2 a 850°C para electrodos de aire compuestos por 80% de GDC y 20% de PNO en peso. Estos hallazgos confirman que los electrodos de CPGO son excelentes candidatos para aplicaciones SOC.

Ruddlesden–Popper (RP) lanthanide nickelate materials are of current interest for their potential application as air/oxygen electrodes in solid oxide fuel cells (SOFC) and solid oxide electrolysis cells (SOEC), oxygen pumps, oxygen sensors and catalytically active membranes for membrane reactors, as they present mixed electronic and ionic conductivities [1]. These innumerable applications are possible due to their high surface exchange (kex) and chemical diffusion (Dchem) coefficients being comparable with that of other solid oxide cells (SOC) materials, like perovskites and double perovskites [2,3]. Among the lanthanide nickelates, Pr2NiO4+δ (PNO) demonstrates the highest rate of surface exchange activity in comparison with manganite or cobaltite-based materials [4], also displaying the highest oxygen diffusivity among the nickelates in literature [5].

The most prominent issue with nickelate-based electrodes is their reactivity with standard electrolyte materials, which induces the formation of insulating phases that increase the polarization resistance (Rpol) [6]. Even so, several studies have demonstrated that nickelates are among the most promising oxygen electrodes for electrolysis applications [7,8]. With the particular use of ceria-based electrolytes, high-resistivity phases are not formed, and the cell performance can achieve stability over time [9]. The air electrode/electrolyte compatibility has been studied for gadolinium-doped ceria (GDC), yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ), and lanthanum–strontium–gallium manganite (LSGM), revealing that YSZ and GDC are highly reactive with PNO at 900°C for over 24h, while reactivity is not as evident in LSGM for up to 72h at 1000°C [10]. In the presence of GDC, PNO decomposition into PrOx and Pr4Ni3O10−δ without further formation of NiO occurs at 800°C [11], as well as the formation of cubic fluorite Pr- and Gd-doped ceria phases (CPGO) [12]. These composites were electrochemically tested on oxygen electrodes fabricated from PNO and GDC mixtures on single-microtubular cell configurations [12]. This configuration was also characterized for 150h of combined reversible SOFC/SOEC operation without degradation of the air electrode [13]. Similarly, ceria and PNO mixtures have been used as diffusive layers to repel the formation of insulating phases in planar cells [14]. Even with interdiffusion, the degradation rate of the PNO–GDC system is low in the long term [15], while featuring more suitability than YSZ and SSZ at intermediate temperatures [16] due to the lower densification of the ceria that can prevent the agglomeration of particles. It has also been demonstrated that CPGO interlayers diminish the nickelate decomposition and boost the SOFC power density [17].

The CPGO phase formed by the PNO–GDC interaction is analogous to the Ce1−xPrxO2−δ (PDC) lanthanide-ceria system, known for its high oxygen availability [18,19] and high electrical conductivity [20,21]. Increasing the praseodymium content in PDC also increases the oxygen vacancy concentration and the total conductivity of the material [22]. This effect benefits SOC air electrodes, where a mixed oxide with a composition near x=1 (single-phase) is the most favorable composition for an active layer. However, many authors have reported a high thermal and chemical expansion for these oxides [14,23], although, for x<0.2, the thermal and chemical expansions seem to be more suitable for SOFC operation [24].

This article reflects on the structural and electrochemical characterization of CPGO compositions formed by sintering reactions of PNO and GDC. These mixtures have demonstrated good compatibility with YSZ electrolytes, confirming their interest as air electrodes for SOCs [12]. However, previous studies do not delve into the structural, kinetic, and electrochemical of these oxides in air electrode applications for SOC. This study intends to compare the behavior of these properties between doped ceria and PNO electrodes. For this purpose, we have selected different PNO and GDC mixed oxide compositions obtained by sintering at 1450°C. The ratio compositions were chosen to verify the limits of interdiffusion of praseodymium into the ceria lattice and the possible influence of the secondary phases on the electrochemical performance of PNO–GDC electrodes. The basis for selecting the same sintering temperature for composites with different PNO content is to ensure the high density of the samples, particularly in ceria. The structural studies of the air electrodes include X-ray diffraction (XRD) and dilatometry experiments, focusing on the effect of cation interdiffusion at high-temperature sintering and thermal expansion at usual SOC operation temperatures. Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) and electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS) are performed to determine the elemental composition of the CPGO phases and to track possible Ce and Pr valence changes. We also focus on the electrochemical performance via the electrical conductivity relaxation method (ECR), measuring the kex and Dchem coefficients, as the time domain analysis of the ECR response is based on the “ideal” behavior of the diffusion process. This approach is applied to the system, previously obtaining the changes in the driving force from a resulting oxygen flux [25]. Finally, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analyses are conducted in symmetrical cells to validate their SOC electrode performance.

ExperimentalSample preparationThe samples are prepared from commercial ceramic powders Pr2NiO4+δ (Marion Technologies) and Ce0.90Gd0.10O1.95 (GDC10-M, Fuelcell Materials), mixed with polyvinyl alcohol in an agate mortar at a ratio of 0.15ml per gram of the powder mixture, until a uniform compound was visible and then inserted into a latex sheath to form cylindric samples. The bars are then uniaxially pressed at 2000bar and sintered at 1450°C for 2h at a rate of 5°Cmin−1. The samples were structurally and microstructurally evaluated in three different PNO–GDC compositions: 20% GDC+80% PNO by weight (C20), 80% GDC+20% by weight (C80), and 100% PNO for comparison. The approximate dimensions of the samples were about 7.0×2.5 (length×diameter in mm2). For the electrochemical studies, symmetrical cells were also prepared using >98% dense GDC pellets as electrolytes, with a diameter of ∼18mm and thickness of ∼1.2mm. In this configuration, thick and dense GDC electrolytes ensure that no electronic leakage is taking place at high temperatures. Electrode slurries (terpineol-based) of PNO and C80 compositions were fabricated and then deposited on both sides of GDC pellets, and subsequently sintered at 1100°C for 2h in air.

X-ray diffraction and dilatometry testsXRD patterns of the milled powders were collected using Cu-Kα radiation in a D-Max Rigaku instrument. XRD powder analysis was performed using the FullProf Suite [26] for phase quantification and lattice parameter determination. Dilatometry tests under air were performed on the prepared air electrodes at a rate of 2°Cmin−1 from RT to 1450°C using a thermomechanical dilatometer analyzer (Setaram, SETSYS 200).

The XRD analysis is performed with crystal structure files retrieved in the CIF format from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) database from FIZ Karlsruhe [27]. The structure information is converted to PCR format to process the XRD datasets with the LeBail and Rietveld methods using the Fullprof software [26]. With the LeBail method, the main crystalline phases and lattice parameters are identified by the search-match process of extracting the 2θ positions of the measured peaks and comparing them to the peak positions of all known phase structural models stored in a database. This procedure is followed by a Rietveld refinement to obtain the phase quantification of, where phases with peak positions matching the observed ones are added to the refinement project. The final Rietveld refinement parameters are provided in the Supplementary Information (ESI) document in Section S.2.

EDS-STEM and EELSFor the quantitative compositional analysis of the samples, energy dispersive spectroscopy in a scanning transmission electron microscope (EDS-STEM) was performed with an Ultim Max detector (Oxford Instruments) installed in an aberration-probe-corrected STEM (Titan from Thermo Fisher Scientific) operated at 300kV. Energy dispersive spectra were collected in 0.20eV/channel bins. The Cliff–Lorimer method for thin specimens [28] was applied using experimental profiles to ensure maximum fitting accuracy. INCA software from Oxford Instruments was employed for fitting, as the newest Oxford Instruments Aztec software does not include the option of defining our experimental profiles. The Cliff–Lorimer KGdCe, KPrCe and KNiPr sensitivity factors were obtained from GDC, PDC, and PNO powder reference samples (Fig. S.1 in ESI). The cation ratio of these samples was determined by the Inductive Coupled Plasma (ICP) technique. The experimental peak profiles were obtained from Ce, Pr, Gd, and Ni oxides. In this analysis, the selected experimental profile peaks for fitting were Ce-L, Pr-L, Gd-L, and Cu-K. These peaks were used to improve the quantification accuracy because of the overlapping of Gd-Lα1 (6.058keV) and Ce-Lγ1 (6.052keV) lines, and the low levels of Gd and Pr atomic content in C20 and C80, respectively (the fitted spectra is shown in Fig. S.1 of the ESI). Thin TEM specimens were prepared by depositing acetone powder suspensions onto holey carbon Cu grids, except for NiO and Gd2O3 profile samples, in which Au grids were employed as Ni-K and Gd-L are too close to the Cu-K lines. Time acquisition was selected to obtain a quantification error (produced by the statistical counting fluctuations) lower than 1%. The experimental errors were estimated using a two-sigma criterion (95% confidence level).

Electron energy-loss spectra (EELS) were acquired in the same STEM as EDS using a Tridiem spectrometer (Gatan) to determine the variations of the oxidation state of Ce and Pr in the CPGO phase. For this purpose, Ce and Pr core-loss spectrum ranges were recorded for the same particles (CPGO and PNO) where the EDS-STEM analysis was performed. The collection semi-angle employed was 51.3mrad with a convergence semi-angle of 24.8mrad. The data were acquired with an energy dispersion of 0.20eV per channel. The spectra obtained were analyzed using the Gatan® Digital Micrograph (DM) software. The core-loss peak intensity error is calculated according to Egerton [29], where the background is sampled only on the low-energy side of the ionization edges and is extrapolated to higher energies.

Electrical characterizationElectrical conductivity relaxation (ECR) measurements were performed by the four-probe technique using a Zahner Zennium galvanostat/potentiostat by obtaining voltage values over time with a current fixed at 10mA. The temperature was measured with a thermocouple near the sample (within 2mm). The cylindrical samples were placed into a Probostat test cell (NorECs) and inserted vertically into a tubular furnace. The temperature dependence of the oxygen transport properties was measured by changing the temperature stepwise from 800 to 600°C. All the experiments were performed by changing pO2 ranges from 0.21 to 0.10atm. The total flux stream was fixed at 83mlmin−1. ECR parameter fitting in this study was analyzed using the MATLAB toolbox ECRTOOLS [30], under a modified cylindrical geometry model.

Symmetrical cells were characterized by EIS to verify the electrochemical performance of the electrodes in air. The air electrode layers were sintered (at 1100°C for 2.0h) on GDC pellets with up/down ramps of 2°Cmin−1. The measurements were performed without current load using 20mV of AC sinusoidal amplitude and a frequency range from 100kHz to 100mHz using a Zahner Zennium electrochemical station. The symmetrical cell configurations are described by the scheme of Fig. 1. In this study, we employ three different air electrode configurations: PNO_CELL (using only PNO as electrodes), C80_CELL (using C80 as air electrodes), and PNO–C80_CELL (a double-layered electrode with a configuration PNO/C80/GDC/C80/PNO), as described in Fig. 1. The electrical contacts are constructed using annealed gold wires of 0.25mm in diameter and covered with gold paint to improve the electrical contact with the sample surface.

Results and discussionCompositional, structural, and microstructural analysisSample compositionThe phase composition of the samples is presented in Table 1. The PNO sample contained about 5% by weight of secondary phases: NiO and Pr4Si3O12. This silicate phase, likely formed during the processing of the raw powder from the supplier, has also been observed in the analog neodymium nickelate (NNO [31]). NiO is likely produced from the nickelate decomposition over 700°C and its effect on the electrical conductivity is almost negligible because of the low content.

Samples used in this study. The phase ratios and lattice parameters were obtained from the XRD analysis, while the CPGO elemental compositions were determined by EDS-STEM.

| Sample | Nominal composition (% by weight) | Density after sintering | Phases identified (% by weight) | Lattice parameters (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNO | PNO | >99% | 95% PNO (primary phase) | 5.3966(6); 5.4474(8); 12.4332(12) |

| 2% NiO | – | |||

| 3% Pr4Si3O12 | – | |||

| C20 | 20% GDC80% PNO | >98% | 38% Ce0.301±0.006Pr0.672±0.006Gd0.028±0.006O2−δ | 5.4013(5) |

| 27% PrOx | 5.4577(7) | |||

| 9% PNO | 5.3913(9); 5.4439(5); 12.4395(7) | |||

| 25% NiO | – | |||

| C80 | 80% GDC20% PNO | >95% | 97% Ce0.747±0.004Pr0.162±0.004Gd0.092±0.004O2−δ (primary phase) | 5.4134(3) |

| 3% NiO | – | |||

The C20 sample presented mainly two fluorite phases corresponding to CPGO and PrOx. The coexistence of these phases has been previously reported [20,32]. The interest in the PNO-rich ceria composition is derived from the previously reported good performance in single SOC as a barrier layer for PNO air electrodes [12]. In addition to the fluorite phases, unreacted PNO and NiO are also present in C20. Fig. S.3 of the ESI shows isolated PNO particles of around 100μm by diameter, which probably accounts for the high non-homogeneity of the sample as the nickelate is not fully decomposed. On the other hand, the C80 phase is composed almost entirely of a single fluorite phase (around 97% by weight). The presence of this phase indicates that a chemical diffusion of Pr into the ceria lattice is taking place [12,19]. Also, there is no unreacted PNO phase in the C80 sample. The NiO phase found in this sample is about 3wt% and we did not observe any reactivity of the ceria by any of the methods described in this work. The reported limit of solubility of NiO in the ceria is about 10 to 12mol% according to Barrio et al. [33]. As the Ni content in the sample is low, we could assume that the remaining Ni was dissolved into the fluorite ceria structure.

Other studies with higher NiO content mixed with the ceria (50mol%) only reported a yield of 3mol% of total Ni-content dissolved in the tetragonal solid solution in our case, according to the Rietveld refinement results [34].

According to McCullough [32], the secondary phases in Ce–Pr–O systems tend to disappear as the Pr content diminishes under 65% by weight. Also, under operating conditions, the coexistence of CPGO and GDC has been previously outlined [11].

The X-ray powder diffractogram of C80 is shown in Fig. 2. The parameters obtained from the Rietveld refinement are given in Table S.2 of the ESI. The weight composition obtained was 97.14% CPGO and 2.86% NiO, with no evidence for the presence of the PrOx phase, according to the best fit (χ2=1.87).

Elemental composition of the CPGO phaseCation interdiffusion into the ceria lattice is determined by quantification of the CPGO phase by EDS-STEM, as reported in Table 1. For the quantifications, particles of the CPGO phase contained in the C80 sample (18 grains of 150nm of diameter on average) and C20 (15 grains of 135nm of diameter on average) were analyzed. Selected particle microstructures and X-ray spectra are shown in Fig. S.2 of the ESI. The C20 Pr content (67% by atom) approaches the reported limits of solubility of Pr into ceria at around 70% by atom similar to PDC [20]. On the contrary, the Ce-Pr ratio of the CPGO phase in C80 was 4.6 with about 9% of Gd by atom.

Ce and Pr oxidation statesThe oxidation states of Ce and Pr in CPGO were identified by EELS-STEM analysis of single-phase grains. We employed this analysis on four particles of 100nm of diameter on average, in both C80 and C20, comparing the intensity ratios of the characteristic M4 and M5 EELS edges of Ce and Pr after background subtraction using a power-law model. These lines represent the 3d3/2→4f5/2(M4) and 3d5/2→4f7/2(M5) electronic transitions [35] and the peak intensity ratio points out the oxidation state [36]. Briefly, a significant presence of the 3+ valence state is reflected in the increase of the intensity of the M5 peak (and consequently in the M5/M4 ratio) with respect to 4+ valence state.

The M5/M4 peak intensity ratio from GDC (Ce4+) and PNO (mostly Pr3+) reference samples are compared with the values obtained for CPGO in C20 and C80 in Fig. 3. The obtained Ce M5/M4 peak intensity ratio reference for Ce4+ was 0.88±0.06, in good agreement with previous experiments [37], while for CPGO it was 0.79±0.03 in both PNO–GDC air electrodes. The Ce M4,5 peaks in C20, C80, and GDC have the same intensity relationship showing a tendency for the Ce4+ oxidation state. Other authors also found Ce4+ in PDC solid solutions under oxidation conditions using EELS [38] and X-ray absorption near-edge spectra (XANES) [39] experiments. The calculated Pr M5/M4 ratio is 1.25±0.07 for C20 and 1.25±0.20 for C80. Although the relative error in C80 is high, both values are compatible with the one obtained for Pr4+ (M5/M4∼1.28) [35]. These results confirm the expected Pr4+ valence for Pr-doped ceria, as reported in many works [20,32]. This is a good indicator of a possible formation of a high entropy oxide as it favors the incorporation of the dopant into the host lattice, a product of a similar cation size in the dopant and host cation at the same oxidation state. Similarly, EELS M5/M4 ratio analyses consistently match the results obtained for the CPGO lattice parameter predictions with the presence of Ce4+ and Pr4+. Schaube et al. [40] highlighted the importance of point defects for oxygen surface reaction kinetics on doped ceria by PIE experiments. They mentioned that at a higher temperature, the Pr3+ incorporated into the ceria tends to approximate the total Pr content; however, at increasing pO2, the Pr3+ content diminishes. Other authors mentioned that the Pr oxidation state at the surface of PDC deviated significantly from that of the bulk [41,42]Fig. 4.

In PNO reference samples, the Pr M5/M4 peak intensity values obtained for as-received and sintered PNO were 1.55±0.10 and 1.52±0.07, respectively. These values indicate a mixed 3+/4+ valence for Pr according to the expected values in the literature for the Pr M5/M4 ratio [43,44].

As sample C20 presents a high degree of inhomogeneity, it has been discarded from further structural and electrochemical studies. This phase is presented in this section only to determine the solubility limits of PNO in the doped ceria and its structural and microstructural properties in comparison to PNO and C80. The interest in a more stable CPGO phase formation led this analysis toward a focus on the C80 sample, for all the subsequent characterizations.

Lattice parameterTable 1 presents the lattice parameters for samples PNO and C80. The lattice parameters of the nickelate phase reported are consistent with literature values [12]. C80 presents a similar pattern between the lattice parameter and the Pr content in CPGO, according to Kim's empirical method [45] and previous CPGO experiments [23]. The lattice parameters of CPGO follow a linear function of Vegard's rule as CPGO has a fluorite-type cubic crystal structure, and the ionic radii of Pr4+ and Ce4+ are similar. From our calculations, the average Pr oxidation state is 3.94 in C80 (16.2±0.4% Pr by atom), which is in good agreement with the EELS estimations. The obtained experimental value in C80 (a=5.4134Å for 16.2±0.6% Pr by atom) is also compatible with the recorded by Cheng et al. [23] (a=5.4146Å for 15% of Pr by atom). Cheng et al. [23] investigated the lattice parameters evolution with the composition of dopants (Pr, Gd), obtaining theoretical parameters in good agreement with the experimental ones. While Kim's method adjusts well with our experimental data for C80, the data from Cheng et al. does not follow this kind of linearity because the Gd content is a constant (10% by atom).

Thermal expansion coefficientThe thermal expansion coefficient (TEC) of C80 was measured from RT to 1450°C (Fig. S.4a in ESI) using the method of differences [46] for a first-order phase transition (refer to ESI section S.2). In this temperature range, the mean TEC for C80 was 14.1×10−6K−1, slightly higher than for YSZ and GDC electrolytes ∼12×10−6K−1[47]. However, the coefficients rose to about 18.1×10−6K−1 and 19.1×10−6K−1 for C80 at 700°C (Fig. S.5 in ESI). Similar changes were noticed by several authors [14,22,48]. These reports suggest a phase transition and could explain the transition temperatures at 650°C (Fig. S.4a). Chockalingam et al. [14] noted this transition of CPGO in Ce0.75Pr0.20Gd0.05O2−δ, a similar composition to C80. Chiba et al. [22] also observed the same transition at 450°C for Ce0.3Pr0.7O2−δ and at ∼550°C for Ce0.8Pr0.2O2−δ This may be related to the ceria temperature of reduction at the surface (around 420°C) and in bulk (around 720°C) [49]. The intermediate state is caused by a thermodynamic factor (equilibrium concentration of oxygen vacancies driven by temperature and oxygen pressure) and a kinetic factor (oxygen diffusion rates in the crystal and ordering of vacancies). The increase in the slope of the curves at high temperatures may be due to the loss of lattice oxygen [14]. Doping praseodymium into ceria induces significant chemical expansion [14,50] that affects the thermomechanical stability of the material. Cheng et al. [23]. found an increase of TEC with the Pr concentration due to a chemical expansion, especially when trying to match the electronic conductivity in the range of ionic conductivity, where more than 12.5% of Pr by atom is needed.

Finally, the change of slope of TEC for C80 in the 650–700°C range of Fig. S.5 is probably related to PNO decomposition, which starts at 700°C [51], expelling PrOx at 800°C [52] that is later incorporated into the cubic ceria fluorite structure producing a lattice expansion and forming the new CPGO phase. This is exemplified by the contraction velocity calculations from dilatometry tests in both PNO–GDC samples, where a peak is observed at around 1100°C (Fig. S.4b in ESI).

Determination of surface exchange and chemical diffusion coefficientsThe kex and Dchem values for lanthanide nickelates at different temperatures are extracted from several sources [5,53–59] and shown as a comparison to the C80 and PNO electrodes in Fig. 4a and b. ECR fitting examples can be found in Fig. S.8. In general, the coefficients are in good agreement with lanthanide nickelates [5,54,60] and doped ceria [40,58,61,62]. The kex coefficient is directly associated with electrocatalytic activity and oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) rate. On the other hand, Dchem is not significantly influenced by the morphology of particles, being more affected by ionic conductivity. The most likely mechanism of diffusion is influenced by apical and interstitial oxygen.

Table 2 summarizes the apparent activation energies for kex and Dchem. The activation energy of PNO's coefficients agrees with the SIMS data [5] in the 700–800°C range. As seen in Table 2, PNO's activation energies of kex (0.38eV) and Dchem (0.88eV) in the 700–800°C range do not differ significantly from Boehm et al. [5] (0.41 and 0.71eV, respectively). However, below 700°C energy decreases which could be influenced by the ECR method. In ECR, the measurements can be in surface, diffusion, or mixed control regimes [30]. Fittings to relaxation data with a lower than 3% standard error mean a re-equilibration in a mixed regime in oxygen kinetic coefficients. The surface-controlled regime, where the estimation of Dchem has higher uncertainty, is usually found at low temperatures, while diffusion control can be seen at higher temperatures. This means that kex values have a higher error at temperatures higher than 650°C as they enter the diffusion regime. A higher error in activation energies was observed in the oxygen surface for PNO-rich samples.

Activation energy values for oxygen surface exchange and diffusion processes in Ln2NiO4±δ (Ln=La, Pr, Nd) and Ce0.9Gd0.1O2−δ mixed oxides at selected temperature ranges and pO2=0.21atm.

| Oxide | ΔT, °C | Activation energy (eV) | Method | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion | Exchange | ||||

| LNO | 450–800 | 0.62 | 1.29 | SIMS | Kilner et al. [65] |

| 600–800 | n/a | 1.35 | PIE | Bouwmeester et al. [56] | |

| PNO | 520–800 | 0.71 | 0.41 | SIMS | Boehm et al. [5] |

| 550–700 | 1.05 | 1.46 | PIE, ECR | Saher et al. [59] | |

| 550–750 | 0.91 | 1.44 | PIE, ECR | Sadykov et al. [58] | |

| 700–800 | 0.88±0.33 | 0.38±0.25 | ECR | This work | |

| 600–800 | 0.40±0.16 | 0.29±0.06 | ECR | This work | |

| C80 | 700–800 | 1.00±0.08 | 0.61±0.06 | ECR | This work |

| NNO | 520–800 | 1.07 | 0.78 | SIMS | Boehm et al. [5] |

Ciucci et al. [30] highlighted the mass transport analogy of Biot number and sensitivity to investigate the measurability of the oxygen diffusion coefficients. In this model, the ECR method considers that the parameters governing the sensitivity are linked to the Biot number, the diffusion and reaction timescales. For a small Biot number, the ECR experiment is sensitive only to oxygen surface exchange, while for a large Biot number only the oxygen diffusion is identifiable. We calculated this relation for the values obtained (Fig. S.9 in the ESI), showing that most of the calculations for kex and Dchem are within the mixed oxygen chemical diffusion and surface exchange control regime. However, the PNO-rich samples approach the oxygen chemical diffusion control regime.

In C80, under similar conditions, the reported activation energy of GDC in the Dchem process is 1.1eV, while for kex is 1.0eV below 650°C [63,64]. The same authors suggested a change in activation energies over 650°C at 2.4eV, which is higher than the 0.61eV obtained in our calculations between 700 and 800°C.

Electrochemical characterizationsElectrical conductivityThe electrical conductivity of C80 maintains values up to σ=0.13Scm−1 at 800°C, while in PNO the electrical conductivity is σ=93.19Scm−1 at 800°C, as shown in Figs. S.6 and S.7 of the ESI. Those values are consistently within the same range as those reported in the literature for PNO [5], PDC [22,66], and CPGO [14,22]. PNO conductivity is substantially higher than the ceria compounds due to the presence of conductive PrNiO3 perovskite layers in the RP structure.

The C80 sample also presents a higher conductivity than GDC, likely driven by a Pr-impurity that narrows the gap between conduction and valence bands. In literature, diverse GDC electrical conductivity values are reported at 800°C ranging from 5×10−4 to 2×10−2Scm−1[67,68], while for PDC, there seems to be an increase of electrical conductivity proportional to the Pr content [69]. For C80, it is important to consider that Pr doping facilitates electronic transition by the formation of an impurity band in between the O-2p valence band and the Ce-4f conduction band [70,71]. Minor dopant additions do not influence ceria-based compounds’ total and ionic conductivity. The contribution of the electron/hole conductivity to the total conductivity increases with temperature, with a significantly lower activation energy for ionic conduction (0.7–0.8eV) than for p-type electronic transport (1.1–1.7eV) [70]. The activation energy calculated for electronic conductivity in C80 was 1.40eV. As a comparison, the activation energy for electronic conductivity of low Pr content CPGO phases is 1.10eV [67].

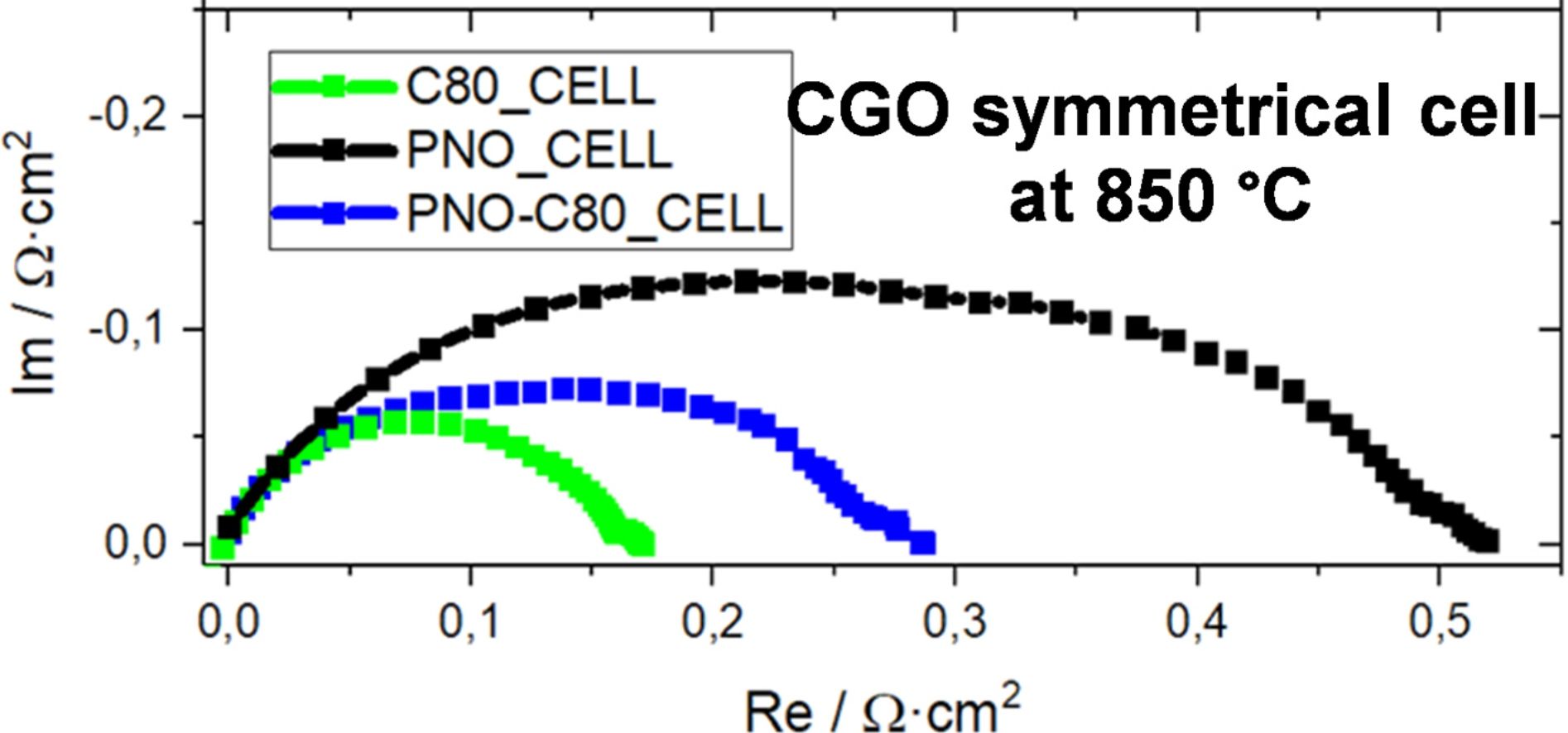

EIS measurements on symmetrical cellsFinally, EIS measurements of the PNO cell and the C80 cell (refer to Fig. 1 for the cell configurations) were carried out and the results are compared in Fig. 5a. Similarly, these cells are compared with the PNO-C80 cell to evaluate the performance of C80 as a barrier active layer. The symmetrical cells were evaluated by a distribution of relaxation times (DRT) to assess the changes of either PNO or the doped ceria composition on the electrode microstructure, and the mechanisms that contribute to the deconvoluted peaks of the Rpol in Fig. S.10 and Table S.3. At 850°C, the Rpol value of PNO cell (0.53Ωcm2) is three times higher than in C80 cell (0.17Ωcm2).

(a) Nyquist plot of C80 compared to PNO and double-layered electrodes at 850°C. (b) Equivalent circuit configuration used in the DRT model. (c) Temperature dependences of Rpol in the temperature range of 700–850°C of PNO and C80. (d) Distribution function of Relaxation Times at 850°C of C80, PNO, and C80/PNO.

According to the existing literature [72] for similar electrodes, the processes from the DRT data could be identified as follows: electron transfer between the electrode and current collector (P1), oxygen ion transfer across the electrodes and the electrolyte interface (P2), oxygen surface exchange (P3), and oxygen diffusion (P4).

DRT peak deconvolution results shown in Fig. 5c, describe how the composition or temperature affects the P1 peak in the 104 and 105 Hz frequency range. Such a high-frequency mechanism is typically associated with interfacial effects in the electrode [73]. The performance of peaks P1 and P2 is similar for C80_CELL and PNO-C80_CELL, however, the compensation effect of the reduction of peaks at lower frequencies suggests an important increase of the effective electrochemically active sites at the electrode/electrolyte interface at 800°C when using the single C80 layer. In the C80 cell at 850°C, P1 is higher, and this process is thermally driven in the order of PNO-C80>C80, possibly influenced by the ceria phase reduction. P2 peaks were generally lower in PNO and PNO-C80 cells, suggesting higher activation than in C80 cell. Also, the double-layered symmetrical cells (PNO-C80) presented a similar behavior with a slight Rpol increase over single-layer cells, indicating that the PNO current collector layer does not affect the performance significantly. However, some effects are observed in Fig. 5c, where DRT peaks between 102 and 105Hz show an improvement of the PNO air electrode when including a barrier layer of C80 in the electrolyte interface. When it comes to the single air electrode layer in C80_CELL, the peaks are considerably diminished below the 104Hz range. In the C80 and PNO-C80 cells, peaks lower than 1Hz did not appear likely due to the extension of the triple phase boundary area for electrochemical oxygen reduction reaction [74], which reduces the gas diffusion polarization resistance.

Comparing the cells below 800°C (Fig. S.10 in the ESI), the processes that affect the Rpol in the frequency range of 103Hz in C80 cell were rate-determining in peak P3, while for the PNO-C80 cell the most limiting process was P4. It was observed that the PNO layer has a detrimental effect on the oxygen surface exchange product of a lack of oxygen dissociation in the air electrode [75]. It is concluded that the polarization resistance values calculated at below 103Hz dominated the total resistances of the cell and hindered the ionic diffusion of the electrochemical reaction. Below 102Hz and 800°C, oxygen diffusion becomes the dominant peak in terms of contribution to the Rpol. The activation energy of the Rpol calculated for PNO-C80 cell (106.0±3.8kJmol−1) is in line with the calculated for PNO cell (103.9±8.3kJmol−1), which is an indication of a major influence of the PNO layer in the active electrochemical zone of the double-layered electrodes. The activation energy of Rpol in the PNO_CELL cell, although higher than our calculations for kex and Dchem, is compatible with other authors’ reported values in Table 2.

On the other hand, as observed in Section 3.2, the C80 sample significantly improved its oxygen surface exchange at 800°C. This was observed in the reduction of peak P3 at this temperature, which is almost eliminated in the C80 cell at 850°C. Similarly, the oxygen diffusion, as evidenced by P4 peaks at each temperature, is diminished for the C80 cell. The rate-limiting mechanism of this electrode appears in peak P2, where O2− surface exchange and ionic transfer at the electrolyte interface dominate.

In general, even though a significant reduction of the Rpol is obtained using PNO–GDC electrodes, further analyses in single SOCs are required under standard SOFC/SOEC operation to validate those findings.

ConclusionsPNO–GDC air electrodes were structurally and electrochemically characterized for their prospect as air electrodes for SOC applications. XRD analysis confirmed a single-phase CPGO formed in C80, whereas coexisting CPGO and PrOx phases were identified in C20. Moreover, the surface exchange and chemical diffusion coefficients showed some of the highest values among doped ceria. The surface exchange measured by the kex values was 2.23×10−6cms−1 at 800°C for C80. Similarly, the chemical diffusion coefficient Dchem in C80 was 7.61×10−8cm2s−1 at the same temperature. The results indicate that PNO–GDC thermal expansion coefficients of 14.1×10−6K−1 are more suitable in the 500–700°C range with standard electrolyte materials, such as YSZ and GDC, and PNO oxygen electrodes. In any case, CPGO-based air electrodes showed an enhanced electrochemical performance over the C80/PNO double-layer air electrode, where we found Rpol values as low as 0.17Ωcm2 at 850°C using a composition of C80 for the oxygen electrode, about three times less than in pure PNO electrodes. Given these findings, PNO–GDC mixtures are confirmed as excellent candidates as oxygen electrodes for SOFC/SOEC applications.

Authors’ contributionsM.A. Morales-Zapata: writing-original draft, validation, formal analysis, visualization, conceptualization, and investigation; A. Larrea: writing-review & editing, supervision, resources, funding acquisition and conceptualization; M.A. Laguna-Bercero: writing-review & editing, supervision, resources, data curation, funding acquisition and conceptualization.

Conflicts of interestThere are no conflicts to declare.

This research has received funding from grants PID2022-137626OB-C31, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 FEDER, UE and grant DGA T02-23R, funded by Gobierno de Aragón. Furthermore, the use of Servicio General de Apoyo a la Investigación (SAI, University of Zaragoza) and the Advanced Microscopy Laboratory (LMA) are also acknowledged. This research was also supported by MCIN with funding from NextGenerationEU (PRTR-C17.I1) within the Planes Complementarios con CCAA (Area of Green Hydrogen and Energy) and it has been carried out in the CSIC Interdisciplinary Thematic Platform (PTI+) Transición Energética Sostenible+(PTI− TRANSENER+).