Community nursing, distinct from hospital-based practice, is increasingly recognized by the WHO as central to health promotion and disease management. However, global workforce shortages are acute and projected to require nine million more nurses by 2030. Chronic and infectious diseases, ranging from respiratory illnesses to diabetes and HIV/AIDS, coupled with population ageing and technological advances, amplify demand for community nurses, particularly in low- and middle-income settings such as Peru. Despite this need, hiring patterns still favor clinical over community roles, and empirical data on how the public perceives community nurses are scarce. Evidence suggests that patients appreciate the autonomy and problem-solving skills of community nurses. In contrast, nurses themselves acknowledge strong ties with families, yet feel constrained by a health model that prioritizes care delivery over prevention.1 Addressing this knowledge gap is crucial; understanding the sociodemographic factors that influence perceptions of community nursing can inform strategies to enhance the effectiveness of these professionals and promote healthier behaviors in diverse populations.

This study adopted a cross-sectional observational design in the southern region of Peru and recruited 405 adults through non-probability sampling. Participants completed the REFCO questionnaire, which assesses community perceptions of nurses’ roles. This instrument is divided into two dimensions (Field trip and Education). The final scoring scale categorizes the role of the community nurse into inadequate (≤18 points) and adequate (≥18 points).2 The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and multivariate models, with binary logistic regression employed to examine factors independently associated with residents’ perceptions of community-nursing roles.

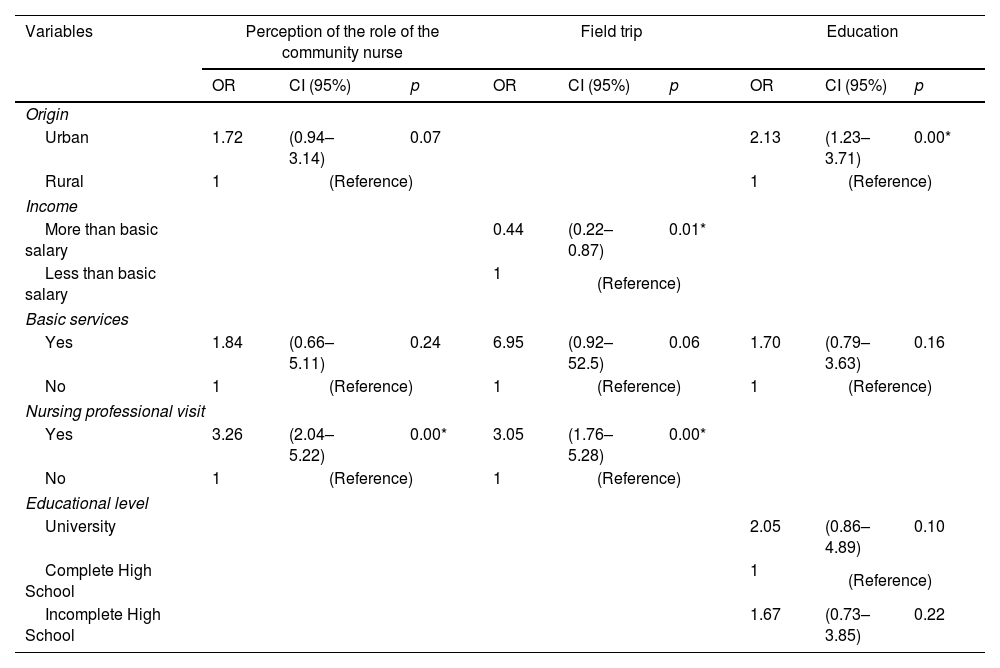

The results revealed that the median age of respondents was 39 years; 60% were women, and 65% lived in urban areas. The multivariate analysis showed that people who had received at least one home visit from a nurse were more likely to perceive the community nurse's overall role as adequate (OR=3.26; 95% CI: 2.04–5.22). In the Field trip dimension, receiving a home visit was associated with a better perception (OR=3.05; 95% CI: 1.76–5.28), whereas having a monthly income below the minimum wage was associated with a lower perception (OR=0.44; 95% CI: 0.22–0.87). In the Education dimension, residing in an urban area increased the likelihood of a positive perception (OR=2.13; 95% CI: 1.23–3.71). We did not find significant associations for other variables such as sex, age, or education level (Table 1).

Multivariate analysis of the general characteristics according to the perception of the role of the community nurse.

| Variables | Perception of the role of the community nurse | Field trip | Education | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI (95%) | p | OR | CI (95%) | p | OR | CI (95%) | p | |

| Origin | |||||||||

| Urban | 1.72 | (0.94–3.14) | 0.07 | 2.13 | (1.23–3.71) | 0.00* | |||

| Rural | 1 | (Reference) | 1 | (Reference) | |||||

| Income | |||||||||

| More than basic salary | 0.44 | (0.22–0.87) | 0.01* | ||||||

| Less than basic salary | 1 | (Reference) | |||||||

| Basic services | |||||||||

| Yes | 1.84 | (0.66–5.11) | 0.24 | 6.95 | (0.92–52.5) | 0.06 | 1.70 | (0.79–3.63) | 0.16 |

| No | 1 | (Reference) | 1 | (Reference) | 1 | (Reference) | |||

| Nursing professional visit | |||||||||

| Yes | 3.26 | (2.04–5.22) | 0.00* | 3.05 | (1.76–5.28) | 0.00* | |||

| No | 1 | (Reference) | 1 | (Reference) | |||||

| Educational level | |||||||||

| University | 2.05 | (0.86–4.89) | 0.10 | ||||||

| Complete High School | 1 | (Reference) | |||||||

| Incomplete High School | 1.67 | (0.73–3.85) | 0.22 | ||||||

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence intervals.

Understanding how communities view the role of nurses is essential because positive perceptions support effective health promotion, disease prevention, and recovery. In this study, residents who had at least one home visit from a nurse were over three times more likely to rate the community-nursing role as adequate. Direct outreach builds trust and enables tailored advice, but its impact is context-dependent. A study in Ghana reported that villagers were dissatisfied with home visits because minor ailments were inadequately addressed, and logistical challenges limited services.3 Such discrepancies suggest that community members’ education, the quality of nursing care, supervision, incentives, and accessibility all shape perceptions. Socio-economic factors further influence views: respondents earning below the basic salary who received home visits were more positive about nurses’ field trips, echoing research from low-income settings where community health-worker programs improved chronic-disease management and patient satisfaction.4,5 Urban residents perceived the educational role of nurses more favorably, perhaps due to better access to information and resources. Nurse-led education programs have been shown to reduce hospitalizations, enhance patient confidence, and support self-care.6

In conclusion, these findings underscore that while home visits and education are valued components of community nursing, perceptions vary with income, setting, and service quality. Strategies to strengthen community nursing should therefore address training, resource allocation, and socio-economic barriers to maximize their impact.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThe study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the Universidad Peruana Unión (No. 021-134-2022). All subjects gave their informed consent to participate in the study. All procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000).

FundingUniversidad Peruana Unión (UPeU) supported this study.

Declaration of competing interestsThe authors have declared no competing interests.