Under normal conditions, there is a small volume of fluid in the pleural space as a result of the balance between its inflow from the pleural capillaries and its drainage through the lymphatics. Pleural effusion (PE) will occur when this balance is disturbed. The initial step in its study is to determine whether PE it is a transudate or an exudate. The first is caused by an alteration in the hydrostatic or oncotic pressure of both the pleural capillaries and the pleural space, without any structural damage to the pleura and with a simple differential diagnosis. In the second, there will be an alteration in fluid flow (increased inflow due to increased permeability of the pleural capillaries or decreased reabsorption due to blocked lymphatic drainage) with damage to the pleural surfaces. Diagnosis is more difficult and more complex biochemical determinations are often used to determine the etiology. A careful clinical history and physical examination together with a good knowledge of the movement of pleural fluid and the information provided by its analysis, obtained by thoracentesis, a simple and safe technique, would allow the family physicians to establish the presumptive diagnosis of the etiology of pleural effusion in about 95% of cases. In this review we provide guidelines as to which specific markers may be useful in the diagnosis of pleural effusion in the Primary Care setting.

En condiciones normales, existe un pequeño volumen de líquido en el espacio pleural como resultado del equilibrio entre su entrada por los capilares pleurales y su drenaje a través de los linfáticos. El derrame pleural (PE) se produce cuando se altera este equilibrio. El paso inicial en su estudio es determinar si el PE es un trasudado o un exudado. El primero se produce por una alteración de la presión hidrostática u oncótica tanto de los capilares pleurales como del espacio pleural, sin que exista daño estructural de la pleura y con un diagnóstico diferencial sencillo. En la segunda, habrá una alteración del flujo de fluidos (aumento de la afluencia por aumento de la permeabilidad de los capilares pleurales o disminución de la reabsorción por obstrucción del drenaje linfático) con daño de las superficies pleurales. El diagnóstico es más difícil y a menudo se utilizan determinaciones bioquímicas más complejas para determinar la etiología. Una historia clínica y una exploración física cuidadosas, junto con un buen conocimiento del movimiento del líquido pleural y la información que proporciona su análisis, obtenido mediante toracocentesis, una técnica sencilla y segura, permitirían a los médicos de familia establecer el diagnóstico presuntivo de la etiología del derrame pleural en aproximadamente el 95% de los casos. En esta revisión aportamos pautas sobre qué marcadores específicos pueden ser útiles en el diagnóstico del derrame pleural en el ámbito de la atención primaria.

Pleural effusion (PE) is a common occurrence in clinical practice with a prevalence of over 400 cases/100,000 inhabitants.1 It is estimated that 1.5 million pleural effusions are diagnosed annually in the United States.2 This means that most physicians, including Family and Community Medicine specialists, will have to manage PE cases throughout their careers, so it is necessary for them to acquire a basic knowledge of pleural fluid analysis (PFA) to at least have an adequate approach to its management.3

More than 60 recognized causes can lead to PE, including local pleural processes, underlying lung, systemic, and multi-organ dysfunction, and drug-induced disease.4 However, in a series of more than 3000 patients who underwent consecutive diagnostic thoracentesis, more than 75% were due to only four etiologies: heart failure, pneumonia, neoplasia and tuberculosis.5

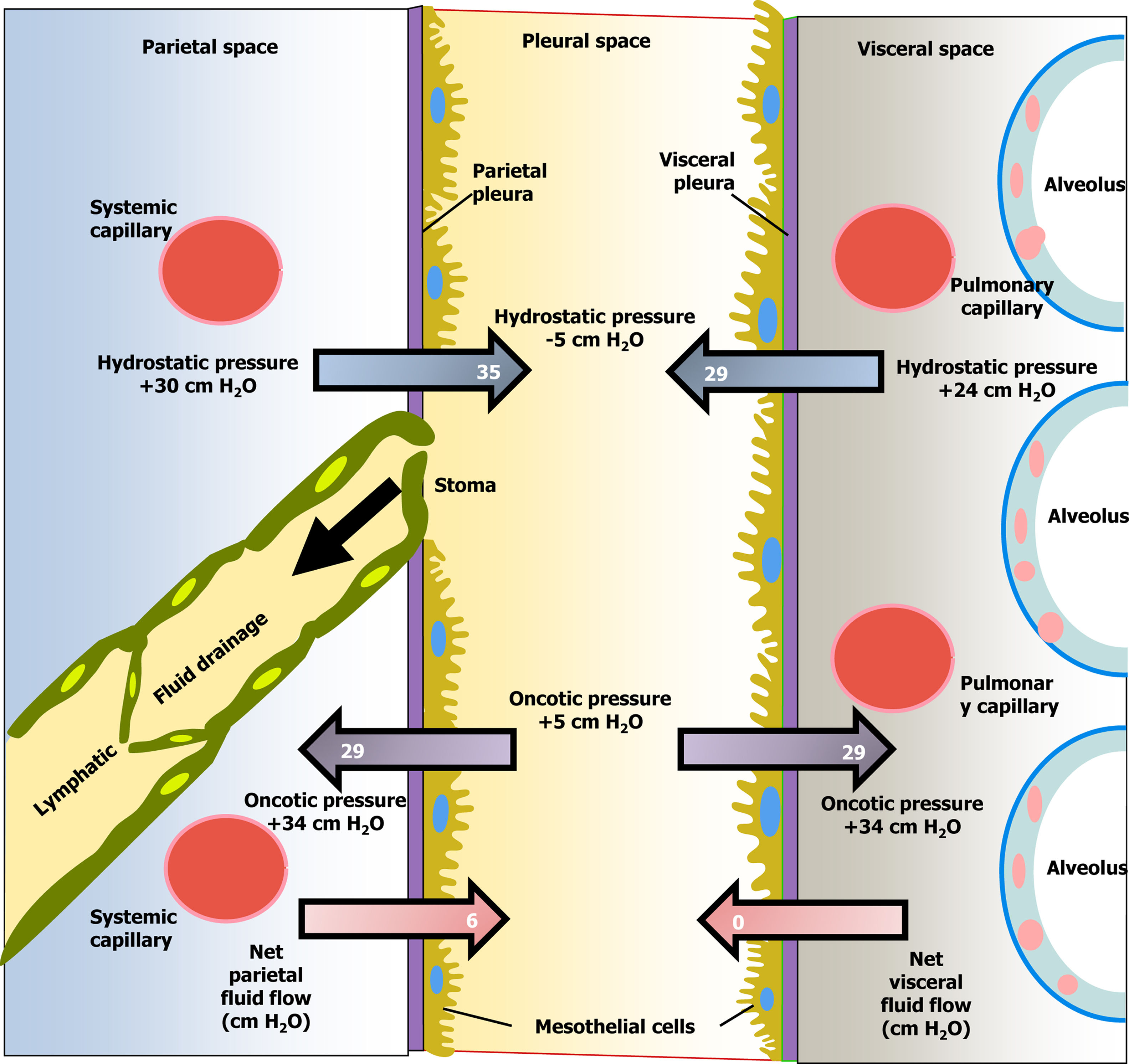

Pleural fluid movementPE is the accumulation of fluid in the pleural space as a result of an imbalance between its formation and absorption by the pleura (Fig. 1).3 There are two main reasons why pleural fluid (PF) accumulates in the pleural space: the first is because there is a change in the hydrostatic/oncotic pressures between the pleural capillaries and the pleural space, while the pleural surfaces remain intact [increased capillary hydrostatic pressure (heart failure), decreased plasma oncotic pressure (hypoalbuminemia), or decreased intrapleural hydrostatic pressure (pulmonary atelectasis)]. This group would include pleural transudates. The second major cause is when there is a flow disturbance. In these cases, the disease causing the PE affects the pleural surfaces, increasing the permeability of the pleural capillaries and allowing a greater outflow of both fluid and solutes into the pleural space (pneumonia, neoplasms, etc.). Other situations, such as obstruction of the lymphatic flow, through which the PF drains (neoplasia), or rupture of the thoracic duct (chylothorax), could also produce PE. This second group consists of exudates. Finally, fluid could also reach the pleural space from the abdomen through diaphragmatic defects (by pressure gradient). In this case, the fluid would be either a transudate or an exudate, depending on its origin in the abdomen.

Diagram of the movement of pleural fluid in the pleural space under normal conditions.

Thoracentesis is a simple and safe technique that, in experienced hands, will be instrumental in determining the etiology of PE.4 Following thoracentesis and the information provided by a detailed clinical history and physical examination, it is estimated that a definitive, or presumptive, diagnosis should be reached in about 95% of cases.6 The most common complications following thoracentesis are pneumothorax (which rarely occurs, necessitating chest drainage) and vagal reaction. In experienced hands, a pneumothorax rate of 0.025% has been reported7 and is usually not necessary to perform a chest X-ray after the procedure, unless the patient's clinical symptoms after the puncture recommend it.8 A vagal reaction can occur in situations of anxiety, pain, or the sight of blood. In these cases, it would be advisable to administer atropine before beginning the test. If a vagal reaction occurs, the procedure should be terminated, the patient placed in the Trendelemburg position, and their vital signs monitored. Recovery usually occurs within 15min.

Thoracentesis should be performed under ultrasound guidance to increase diagnosis yield and to minimize risks. In most patients, no pre-testing is required prior to the technique, and no premedication is necessary, but if there is a risk of vagal reaction, 1mg of atropine can be injected intramuscularly or subcutaneously 30min before the test. If the needle is inserted just above the upper edge of the lower rib, the risk of injury to the vasculonervous bundle is significantly reduced. After cleaning with povidone iodine (or with chlorhexidine) and anesthetizing the area locally with lidocaine or 1–2% mepivacaine, a 21–22G needle connected to a three-way stopcock and a 50mL syringe is introduced. These instruments, together with minimal dressing material, are sufficient to withdraw the fluid gradually and send it to the laboratory for analysis.9 The main contraindication to the test is the risk of bleeding. There is usually no problem if the platelet count is higher than 50,000/μL. In anticoagulated patients, or those at potential risk of bleeding, thoracentesis is still safe if small bore needles are used. Puncture of infected areas of skin, or extensive burns, should also be avoided.7 Therapeutic thoracentesis is indicated for patients with chronic, recurrent pleural effusion (PE) who have a short life expectancy, generally no longer than a month, with the goal of relieving dyspnea. This is the case with neoplastic PEs, or those due to heart or liver failure that are refractory to treatment.4 The technique is similar to that of conventional thoracentesis but uses a longer needle (5.5cm) that acts as a guide for the 14–18G catheter. It is not recommended to remove more than 1–1.5L within 24h to avoid ‘ex vacuo’ pulmonary edema.9 The procedure can be performed at the health center or even in the patient's room. In both settings, the assistance of a nurse is required.

Samples should be collected in bottles for microbiology (8–10mL), biochemistry (5mL) and cytology (50mL would be desirable).4 If infection is suspected, some of the fluid should be sent in blood culture bottles to microbiology and some should be drawn into a heparinized syringe, which should then be capped, so as not to expose it to ambient air, and the pH can be determined. If the fluid is frank pus, its pH should not be analyzed as it could obstruct the gas analyzer.10 Samples should be sent at room temperature as soon as possible (under the same conditions as a blood specimen), but if a delay is anticipated, they can be refrigerated at 4°C for up to 14 days without deterioration in the diagnostic yield of malignancy.4

Thoracic ultrasound (TU) is a harmless, transportable, low-cost test with a relatively short learning curve that allows real-time imaging.11 Its role is to identify PE (location, depth, loculation and septa) and to guide diagnostic procedures such as thoracentesis, but also percutaneous pleural biopsy or thoracic drainage.12 In a meta-analysis of 12 studies with 1554 patients, TU had significantly higher sensitivity and specificity for detecting PE than simple radiography (94% and 98%, respectively, vs. 51% and 91%, respectively)13 and can also detect smaller volumes of PF than plain radiography.14

Pleural fluid analysisAppearance and odourA clear, transparent or straw-coloured fluid suggests a transudate, but a paucicellular exudate cannot be excluded. If the PE is hematic and there is no history of trauma, the differential diagnosis would be benign asbestosis, Dressler's syndrome, pulmonary infarction or neoplasia. A hemothorax is usually due to penetrating trauma or an invasive procedure and the hematocrit of the fluid will be ≥50% of that of the blood. Milky fluid may correspond to a chylothorax, pseudochylothorax or empyema. On centrifugation, the supernatant becomes clear in the latter and remains milky in the former.15 Other features and odours are listed in Fig. 2.

Transudates and exudatesPEs are classified into two main groups: transudates and exudates. In the former, the fluid contains few solutes16,17 (Fig. 2), the diagnosis is usually clinical and further diagnostic tests are usually not necessary. In exudates, increased capillary permeability, or obstruction of lymphatic drainage, will result in higher PF concentrations of proteins and other solutes [e.g. lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)] than in transudates; the differential diagnosis is broader (Fig. 2) and further diagnostic testing is usually necessary.

Light's criteria are used to differentiate between the two types of effusions. A transudate is considered to be a transudate if: the PF protein/serum ratio ≤0.5; the PF LDH/serum ratio is ≤0.6 and the LDH in PF is ≤2/3 of the upper normal limit in blood.18 It is sufficient if only one of the criteria is not met for the fluid to be considered an exudate. In the article by Light et al., 97.9% of transudates were correctly classified whereas, currently, 25% of transudates are misclassified as exudates.19 These discrepancies could be explained by the fact that in the original series almost all thoracenteses were performed before diuretic treatment was started (a rare occurrence nowadays) and because diuretics are now more potent than those available at the time. These drugs, by increasing diuresis, increase the concentrations of various solutes in the pleural fluid sufficiently to meet the biochemical characteristics of exudate. In these situations, it is very practical to use PF cholesterol values to make this differentiation, as no blood sample needs to be obtained simultaneously. Values above 55mg/dL would be in favor of exudate.20 However, it has not been possible to demonstrate superiority of one test over the other.21

Nucleated cellsThe behaviour of the cellular components of the PF can help to focus the differential diagnosis of a PE.16 Transudates usually do not exceed 1000cells/μL, mostly lymphocytes; if it exceeds 10,000cells/μL, the PE is usually due to pleural infection, acute pancreatitis, liver abscess, pulmonary infarction or systemic lupus erythematosus. A count greater than 50,000cells/μL may only be seen in complicated infectious PE and empyema.

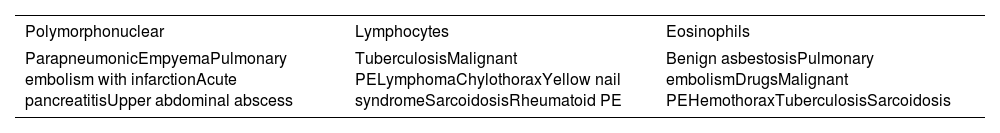

The predominant nucleated cell type in PF is also relevant.22 When neutrophil is the predominant cell (≥50% of the cell count) the cause of PE is an acute inflammatory disease (pneumonia, pancreatitis, subphrenic abscess or pulmonary embolism), as pleural aggression attracts this cell to the pleural space. When acute pleural damage ceases, mononuclear cells (predominantly lymphocytes ≥50%) become the predominant population, as in neoplastic diseases or tuberculosis. An eosinophilic PE (≥10%) should be studied like any PE as eosinophils are not an indicator of benignity (Table 1). The presence of macrophages in the PE is common, but their diagnostic value is limited.22

Etiology of pleural exudates according to their cellular predominance.

| Polymorphonuclear | Lymphocytes | Eosinophils |

|---|---|---|

| ParapneumonicEmpyemaPulmonary embolism with infarctionAcute pancreatitisUpper abdominal abscess | TuberculosisMalignant PELymphomaChylothoraxYellow nail syndromeSarcoidosisRheumatoid PE | Benign asbestosisPulmonary embolismDrugsMalignant PEHemothoraxTuberculosisSarcoidosis |

PE, pleural effusion.

Cardiac myocytes, in response to increased pressure and distension of the cardiac chambers, secrete natriuretic hormones such as N-terminal fragment of pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), easily measurable in both blood and PF. A value of this marker above 1300pg/mL has a diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for PE secondary to heart failure of 93% and 89.9% respectively.23 Its main usefulness lies in the fact that, in the presence of normal NT-proBNP values, heart failure can be excluded as a cause of undiagnosed unilateral PE.

Pleural pH should be measured on a blood gas analyzer, ensuring that the sample is collected anaerobically, and analyzed within an hour of collection, avoiding factors such as ambient air, anaesthetic (lidocaine), or heparin from the syringe altering the results. Low pH values (<7.30) are due to increased metabolic activity in the PF and suggest aetiologies such as pleural infection, rheumatoid PE or advanced neoplasia. In the setting of suspected pleural infection, a pH <7.20 suggests a complicated infectious PE and indicates that chest drainage will most likely be necessary to resolve the effusion24 (Table 2). Low PF glucose values (<60mg/dL) may be related to those of pH and, in the setting of infection, indicate the need for chest drainage to resolve the PE24 (Table 2).

Other useful biochemical determinations in pleural fluid.

| Parameter | Cut point | Diagnostic utility |

|---|---|---|

| Adenosine deaminase | >35U/L | Consider tuberculosis |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen | >50ng/mL | Consider pleural metastases |

| Cholesterol | >55mg/dL>250mg/dL | ExudateConsider pseudochylothorax |

| N-terminal fragment of pro-brain natriuretic peptide | ≥1300pg/mL | Consider heart failure |

| Glucose | ≤60mg/dL | Consider pleural infection (probable need for chest drainage), rheumatoid PE, or advanced neoplasia |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | ≥1000UI/L | Consider pleural infection (probable need for chest drainage) |

| pH | <7.20 | Consider pleural infection (probable need for chest drainage), rheumatoid PE, or advanced neoplasia |

| C-reactive protein | >45mg/L>100mg/L | Consider pleural infectionConsider complicated pleural infection |

| Total proteins | ≥5g/dL≥7g/dL | Consider the possibility of tuberculosisConsider Waldeström macroglobulinemia, multiple myeloma, or pseudochylothorax |

| Triglycerides | ≥110mg/dL | Chylothorax |

PE, pleural effusion.

C-reactive protein is elevated in pleural infections and also differentiates uncomplicated from complicated infections (>100mg/L)24,25 (Table 2). Its specificity increases if associated with a predominance of polymorphonuclear cells in the PF, or a pH <7.20.26

Adenosine deaminase is localized in different cell types, including lymphocytes and neutrophils, and is particularly elevated in tuberculous PEs, in which it has a high diagnostic yield.27 Approximately 70% of empyemas and 10% of malignant PEs (50% in the case of lymphomas) exhibit high levels of ADA.28 When ADA concentrations are extremely high (>250U/L), empyema or lymphoma is suspected.

If malignant PE is suspected, certain biomarkers may be useful. Cytology is positive in almost 70% of malignant PEs (and more in adenocarcinomas). The classical markers (carcinoembryonic antigen, cancer antigen 125, cancer antigen 15-3, cancer antigen 19-9) have a high specificity (85–96%) and a low sensitivity (25–55%), which is why it is recommended to determine them simultaneously.15 If the morphological differentiation of the cells is complex, immunohistochemistry can help differentiate between metastases from adenocarcinoma, mesothelioma, lymphoma or leukaemia.

A PF total protein ≥7g/dL requires ruling out Waldeström's macroglobulinaemia,29 multiple myeloma or pseudochylothorax. An LDH concentration ≥1000IU/L is found in rheumatoid PE30 and in the fibrinopurulent and organizative phases of pleural infections, indicating the need for chest drainage to resolve the effusion.24 Amylase measurement is not justified, unless pancreatic disease (acute pancreatitis, pleuropancreatic fistula) or esophageal rupture (PF/serum amylase >1)31 is suspected. In the presence of a milky PF, triglycerides >110mg/dL confirm chylothorax.32 PF cholesterol >250mg/dL is diagnostic of pseudochylothorax.

Application in Primary CarePrimary Care constitutes the cornerstone of care for chronic patients.33,34 The fact that the population is increasingly aging, with a consequent rise in chronic illnesses, means that more and more people with such diseases – oncological or advanced degenerative conditions – are becoming strong candidates for developing a PE. In this context of patients with oncological or advanced degenerative conditions, it is highly likely that in the coming years, minimally invasive, simple, and safe techniques and procedures will be incorporated into the portfolio of Primary Care services and home support teams, and will be performed in health centers and even in patients’ own homes. Thus, the introduction of TU in Primary Care12,35 opens the door for thoracentesis to undoubtedly become one of these procedures, this would avoid inconvenience to patients and reduce costs, as neither they nor their families would have to travel to the hospital. Although there is currently limited evidence in this regard, Primary Care support teams have performed therapeutic thoracentesis for palliative purposes in patients’ homes, and their conclusion is that these procedures are useful, safe, and not overly complex.36,37 Broader and more robust experiences than those currently available with palliative thoracentesis in the Primary Care setting will be necessary before its implementation in this healthcare context. In addition, further studies will be needed to demonstrate the technical and competency feasibility of new indications for thoracentesis in Primary Care.

ConclusionsThe cost-effectiveness of diagnostic thoracentesis will be significantly increased if, in addition to a detailed history and physical examination, a good knowledge of the pathophysiology of PE and information provided by PFA is used to correctly to interpret its results (Fig. 3).

Diagnostic algorithm of pleural effusion. ADA, adenosine deaminase; CRP, C-reactive protein; CT, computed tomography; HF, heart failure; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NT-proBNP, N-terminal fragment of pro-brain natriuretic peptide; PF/S, pleural fluid/serum ratio; VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery.

All authors have contributed equally to this manuscript.

Ethical considerationsThis narrative review did not involve human participants, animals, or identifiable personal data, and therefore did not require ethical approval. No funding was received for the preparation of this manuscript.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.