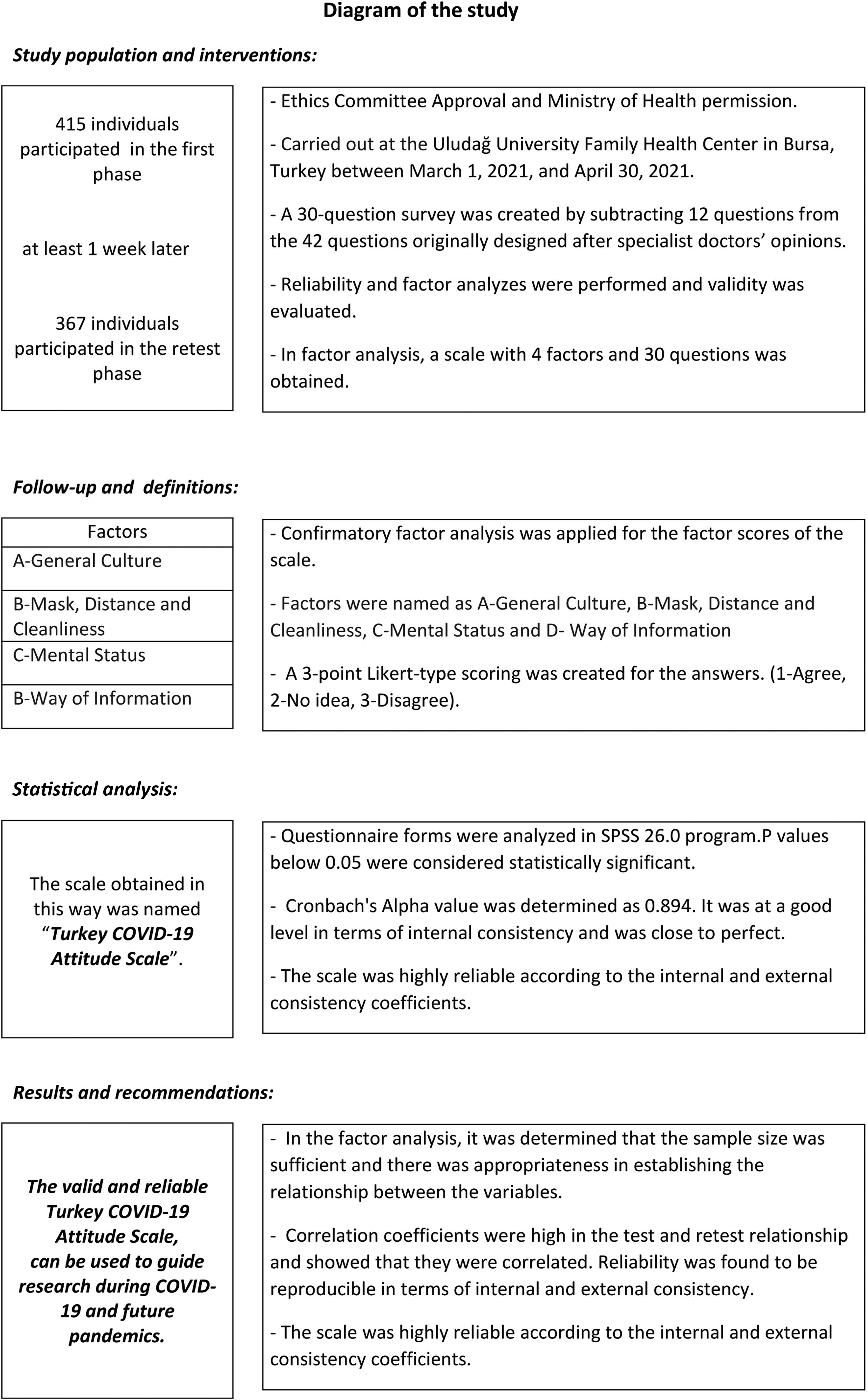

To evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of individuals about COVID-19 and to develop a valid and reliable scale that can measure these items about COVID-19 and other similar pandemic processes.

DesignMethodological scale study with a quantitative approach.

SiteCarried out at the Uludağ University Family Health Center in Bursa, Turkey.

Participants415 individuals in the first phase and 367 in the retest phase.

InterventionsCarried out between March 1, 2021, and April 30, 2021.

Main measurementsReliability and factor analyses were performed and validity was evaluated. In factor analysis, a scale with 4 factors and 30 questions was obtained. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was applied to the factor scores of the scale. Factors were named A-General Culture, B-Mask, Distance and Cleanliness, C-Mental Status, and D-Way of Information. A 3-point Likert-type scoring system was created for the responses.

ResultsCronbach's alpha value was 0.894. In factor modeling, 3 of the confirmatory factor analysis fit indices were good and 4 of them were acceptable, so our model was found to be appropriate. The scale was highly reliable, according to internal and external consistency coefficients. The scale was named the Turkey COVID-19 Attitude Scale. p values<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

ConclusionsThe valid and reliable Turkey COVID-19 Attitude Scale, which we developed to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of individuals about COVID-19, can be used to guide research during COVID-19 and future pandemics.

Evaluar los conocimientos, actitudes y comportamientos de los individuos sobre la COVID-19 y desarrollar una escala válida y confiable para medir estos ítems sobre la COVID-19 y otros procesos pandémicos similares.

DiseñoEstudio de escala metodológica con enfoque cuantitativo.

EmplazamientoCentro de Salud Familiar de la Universidad de Uludağ, en Bursa, Turquía.

Participantes415 individuos en la primera fase y 367 en la fase de retest.

IntervencionesRealizadas entre el 1 de marzo de 2021 y el 30 de abril de 2021.

Mediciones principalesAnálisis de confiabilidad y factoriales para evaluar la validez. Se obtuvo una escala con cuatro factores y 30 preguntas. Se aplicó el análisis factorial confirmatorio (AFC) a las puntuaciones de la escala. Los factores se denominaron A-Cultura general, B-Máscara, distancia y limpieza, C-Estado mental y D-Vía de información. Para las respuestas se creó un sistema de puntuación tipo Likert de tres puntos.

ResultadosEl valor alfa de Cronbach fue de 0,894. Tres de los índices de ajuste del análisis factorial confirmatorio fueron buenos y cuatro de ellos aceptables, por lo que se consideró el modelo como apropiado. La escala resultó altamente confiable, según los coeficientes de consistencia interna y externa. Se denominó Escala de Actitud de Turquía COVID-19. Los valores de p < 0,05 se consideraron estadísticamente significativos.

ConclusionesLa Escala de Actitud de Turquía COVID-19 válida y confiable, desarrollada para evaluar el conocimiento, las actitudes y los comportamientos de las personas sobre COVID-19, se puede utilizar para guiar la investigación durante COVID-19 y futuras pandemias.

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pandemic to be an international public health emergency in 2020.1 The influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in 2009 was also an important public health issue and provided important experience for managing future pandemics. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown the importance of obtaining information about new diseases, making decisions in the face of deficiencies and difficulties, providing an attitude, and taking action.2 Individual knowledge and attitude are as important as social measures in epidemic management.3,4

To increase attitudes and behaviors among the public, health officials and policymakers should promote belief in knowledge and effectiveness. Future interventions and policies should be developed in a person-centered approach to COVID-19 and targeting vulnerable subgroups.5 Despite the increase in COVID-19 cases, providing adequate information with educational interventions can reduce negative attitudes. Correlations between knowledge, attitudes and practices are important in preventing infection.6–12

A systematic review of the general population showed that the components of knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) towards COVID-19 were at an acceptable level. Using an integrated international system can help to better evaluate these components and compare them across countries.13

The current pandemic highlights the importance of education level in the formation of adequate knowledge, attitudes, and practices, and the importance of providing valid, effective, efficient and continuous information to the public through appropriate channels to increase understanding of COVID-19 measures.14–16

The aim of this study was to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of individuals about COVID-19 and to develop a valid and reliable scale that can guide measurement in COVID-19 and other pandemics.

MethodsStudy design and settingIn this study, 415 individuals who applied to Bursa Uludağ University Family Health Center completed a questionnaire between March 1, 2021, and April 30, 2021. In the retest phase, 367 participants completed the questionnaire. The opinions of 10 specialist doctors were obtained to determined the validity of the 42 items on the questionnaire, in terms of content and scope, prior to participants completing the questionnaire. Based on their feedback, 12 questions were excluded from the question pool because the content validity ratio (CVR) remained below the lower limit of 0.62. The content validity ratio of the remaining questions was 0.91. Reliability and factor analyses for the questions were performed, and their validity was evaluated. In factor analysis, a scale with 4 factors and 30 questions was obtained. Factor analysis was used to determine the factor scores of the scale. Factors were named A-General Culture, B-Mask, Distance and Cleanliness, C-Mental Status, and D-Way of Information. A 3-point Likert-type scoring system was created for the responses (1-Agree, 2-No idea, 3-Disagree). Participants were asked about sociodemographic information in the questionnaire, and they were asked to mark the fit option under the attitude statements.

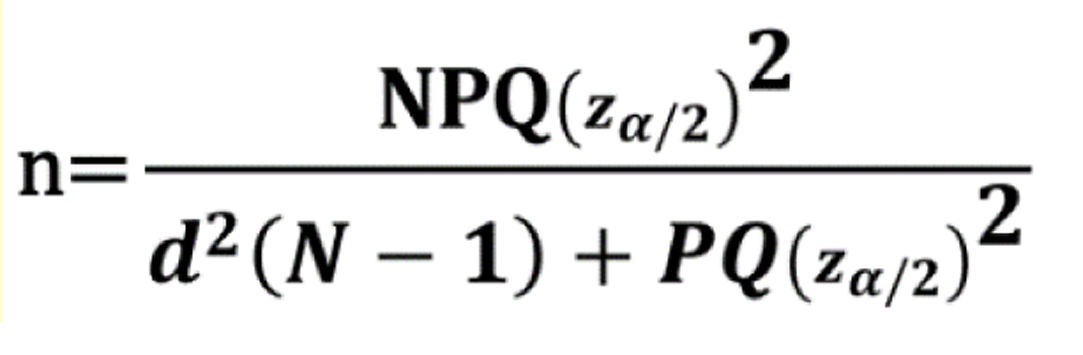

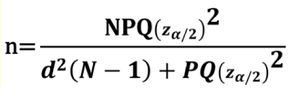

Number of samplesThe number of population for this study was 518382, and it was calculated as a total of 415 people, using P=0.5 to maximize the number of samples to be taken, at 95% confidence level, with a sampling error of 5%, 400 people+15 people as spares. Sample Calculation was done using the following formula.

n: Number of Samples

N: Number of Population

d: Effect Size (calculated with a 5% margin of error)

P: probability of occurrence of X event (0.5 taken for maximum number of samples)

Q: Probability of not seeing event X (1−P)

Zα/2: Standard normal distribution value

Randomization and sample size calculation (Fig. 1).17

Sequence numbers were assigned to patients registered in our Family Health Unit who met the study criteria. Then, random numbers will be generated between 1 and **ni (i. Number of people who meet the inclusion criteria registered in the family health center) by using the (RAND*(b−a)+a) function in excel. Randomization was achieved by taking the patients with row numbers opposite to these generated numbers into the study.

In terms of sample size calculation, individuals who applied to our Family Health Center during the study period, were literate, and had no cognitive adjustment or vision problems were included in the study

EthicsThe study received approval from the Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health (Ref. 2021-02-16T16-37-09), and the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Bursa, Uludağ University, Faculty of Medicine (Ref. 2011-KAEK-26), following the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysisSPSS 26.0 and AMOS 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, United States) programs were used in the analysis of the variables. Spearman's rho test was used to examine the correlations of the variables with each other. In the question pool created for the validity of the research, the opinions of 10 experts for 42 questions were taken and the questions were eliminated according to the content validity indices, and content validity was performed. The smallest content validity index was 0.62 and questions below this rate were not included in the study. 5 questions were excluded because they were below the minimum coverage validity of 0.62. The content validity index of the final questions is 0.91. Afterwards, 50 questionnaires were applied for the pilot study. According to the results of the analysis obtained, 7 questions with low reliability were removed and the study was continued with 30 questions. Re-test for reproducibility from reliability analyzes, Cronbach's Alpha coefficient for consistency and item factor correlations were calculated. Explanatory Factor analyzes were applied for factor constructions. Confirmatory factor analysis from structural equation modeling was applied to confirm the factor structures obtained, and model validity was determined by fit indices. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean (standard deviation), and Median (Minimum/Maximum) and in the tables, while categorical variables were shown as n (%). The variables were analyzed at 95% confidence level, and a p value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

ResultsIn the first stage of the study, 415 people completed the questionnaire; 367 people participated in the retest stage which occurred at least 1 week later. Question 27 was the reverse question. The average scoring of the test questions varied between 2.20 and a maximum of 2.93 (Table 1).

Test questions and scoring.

| No | Questions | Disagree | No idea | Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 point | 2 points | 3 points | ||

| 1 | COVID-19 stands for Coronavirus disease 2019 | |||

| 2 | COVID-19 is caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus | |||

| 3 | The SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 was first identified in 2019 in Wuhan, China | |||

| 4 | SARS-CoV-2 virus is transmitted from person to person | |||

| 5 | COVID-19 can occur in all age groups | |||

| 6 | The main symptoms of COVID-19 are fever, cough, difficulty breathing, chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat, loss of taste and smell | |||

| 7 | COVID-19 causes pneumonia in some patients | |||

| 8 | COVID-19 causes no symptoms or signs in some people | |||

| 9 | Those who have COVID-19 without symptoms can also transmit the virus to other people | |||

| 10 | COVID-19 may have a more severe course in people with diseases such as diabetes, obesity, asthma, heart disease, cancer | |||

| 11 | Symptoms often begin after 4-5 days in a person infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, but can last up to 14 days | |||

| 12 | SARS-CoV-2 virus may show mutation (change) | |||

| 13 | People who have had COVID-19 can be tested to see if they have developed antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 virus | |||

| 14 | Social distancing, mask use, and washing hands with soap and water are very important in protection from COVID-19 | |||

| 15 | It is necessary to be at least 1.5-2 meters away for social (-physical) distance to provide protection from COVID-19 | |||

| 16 | When using a mask, the mouth and nose must be covered to protect against COVID-19 | |||

| 17 | To prevent COVID-19, the face, eyes, mouth and nose should not be touched without proper washing of hands | |||

| 18 | If I have come into contact with a person who is positive for COVID-19, I apply to the health institution by following the mask, distance, and hygiene rules | |||

| 19 | Vaccination is very important in preventing COVID-19 | |||

| 20 | People who have been vaccinated for protection from COVID-19 should also continue to follow the rules of social distancing, use of masks, and washing hands with soap and water | |||

| 21 | I feel stressed due to COVID-19 | |||

| 22 | I am having trouble sleeping due to COVID-19 | |||

| 23 | I have been away from my family, friends and social circle due to COVID-19 | |||

| 24 | I obtained my information about COVID-19 from written and visual media | |||

| 25 | I got my information about COVID-19 by researching it on the internet | |||

| 26 | I obtained my knowledge about COVID-19 by researching scientific medical literature | |||

| 27 | I have never researched COVID-19, I am informed by what I hear from my environment | |||

| 28 | I follow all the rules, including mask, distance, hygiene, to protect from COVID-19 | |||

| 29 | I take vitamin supplements to protect myself from COVID-19 | |||

| 30 | I take herbal supplements to protect myself from COVID-19 |

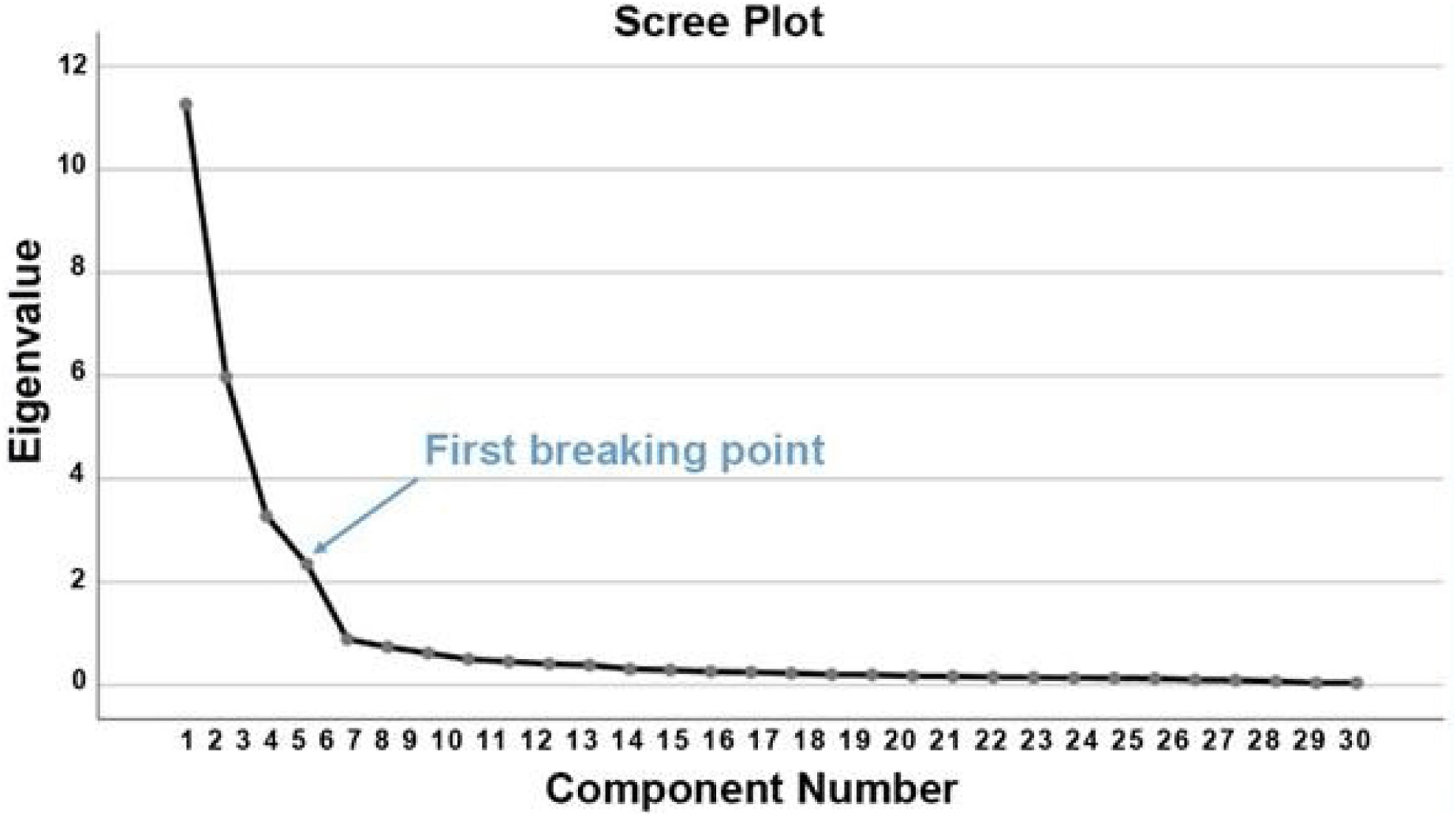

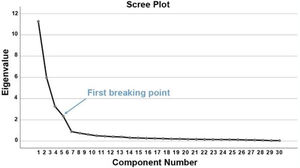

In the factor analysis, it was determined that the sample size was sufficient and that there was a suitability in providing the relationship between the variables. After factor subtraction, the existing 4 factors explain approximately 76% of the variance (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Explained variance and eigenvalues of factors.

| Item | Initial | Extraction (variance explained when subtracted) | Components | Eigenvalues | % of explained variance | Cumulative % of total variance explained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 1 | 0.628 | 1 | 11.265 | 37.551/34.130* | 37.551/34.130* |

| Item 2 | 1 | 0.569 | 2 | 5.971 | 19.902/20.639* | 57.453/54.769* |

| Item 3 | 1 | 0.655 | 3 | 3.276 | 10.920/11.755* | 68.373/66.525* |

| Item 4 | 1 | 0.709 | 4 | 2.344 | 7.813/9.662* | 76.187/76.187* |

| Item 5 | 1 | 0.810 | 5 | 0.891 | 2.969 | 79.155 |

| Item 6 | 1 | 0.840 | 6 | 0.739 | 2.464 | 81.619 |

| Item 7 | 1 | 0.752 | 7 | 0.618 | 2.059 | 83.679 |

| Item 8 | 1 | 0.677 | 8 | 0.500 | 1.668 | 85.346 |

| Item 9 | 1 | 0.879 | 9 | 0.453 | 1.509 | 86.855 |

| Item 10 | 1 | 0.817 | 10 | 0.408 | 1.359 | 88.215 |

| Item 11 | 1 | 0.871 | 11 | 0.387 | 1.290 | 89.505 |

| Item 12 | 1 | 0.873 | 12 | 0.310 | 1.035 | 90.540 |

| Item 13 | 1 | 0.772 | 13 | 0.291 | 0.971 | 91.511 |

| Item 14 | 1 | 0.852 | 14 | 0.262 | 0.872 | 92.383 |

| Item 15 | 1 | 0.862 | 15 | 0.250 | 0.835 | 93.218 |

| Item 16 | 1 | 0.851 | 16 | 0.228 | 0.761 | 93.979 |

| Item 17 | 1 | 0.955 | 17 | 0.202 | 0.675 | 94.654 |

| Item 18 | 1 | 0.911 | 18 | 0.199 | 0.663 | 95.317 |

| Item 19 | 1 | 0.816 | 19 | 0.176 | 0.586 | 95.903 |

| Item 20 | 1 | 0.851 | 20 | 0.168 | 0.560 | 96.464 |

| Item 21 | 1 | 0.622 | 21 | 0.155 | 0.517 | 96.981 |

| Item 22 | 1 | 0.720 | 22 | 0.147 | 0.491 | 97.472 |

| Item 23 | 1 | 0.521 | 23 | 0.141 | 0.468 | 97.940 |

| Item 24 | 1 | 0.665 | 24 | 0.135 | 0.451 | 98.392 |

| Item 25 | 1 | 0.826 | 25 | 0.127 | 0.423 | 98.814 |

| Item 26 | 1 | 0.443 | 26 | 0.103 | 0.344 | 99.158 |

| Item 27 | 1 | 0.689 | 27 | 0.093 | 0.311 | 99.469 |

| Item 28 | 1 | 0.870 | 28 | 0.073 | 0.244 | 99.713 |

| Item 29 | 1 | 0.798 | 29 | 0.044 | 0.145 | 99.858 |

| Item 30 | 1 | 0.753 | 30 | 0.042 | 0.142 | 100.000 |

| KMO and Bartlett's Test: | 0.933 | |||||

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity | p<0.001 | |||||

Extraction method: principal component analysis.

In the factor analysis, the correlation coefficients were determined to be suitable for the factors. Since the first break was at the fourth point in the factor loads, SPSS and scree plots, 4 factors were decided (Table 3).

Factor loadings, eigenvalues and variance explained.

| Component | Component matrixa | Rotated component matrixb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor loadings | Factor loadings | Eigenvalues of factors | Variance explained by factors | |

| Factor 1 | 11.265 | 34.130 | ||

| Item 1 | 0.774 | 0.780 | ||

| Item 2 | 0.747 | 0.715 | ||

| Item 3 | 0.801 | 0.778 | ||

| Item 4 | 0.824 | 0.822 | ||

| Item 5 | 0.885 | 0.880 | ||

| Item 6 | 0.886 | 0.907 | ||

| Item 7 | 0.846 | 0.853 | ||

| Item 8 | 0.812 | 0.792 | ||

| Item 9 | 0.923 | 0.918 | ||

| Item 10 | 0.886 | 0.888 | ||

| Item 11 | 0.909 | 0.918 | ||

| Item 12 | 0.925 | 0.904 | ||

| Item 13 | 0.862 | 0.856 | ||

| Item 19 | 0.920 | 0.953 | ||

| Factor 2 | 5.971 | 20.64 | ||

| Item 14 | 0.882 | 0.883 | ||

| Item 15 | 0.894 | 0.921 | ||

| Item 16 | 0.899 | 0.927 | ||

| Item 17 | 0.888 | 0.919 | ||

| Item 18 | 0.938 | 0.974 | ||

| Item 20 | 0.891 | 0.922 | ||

| Item 28 | 0.851 | 0.903 | ||

| Factor 3 | 3.276 | 11.76 | ||

| Item 21 | 0.883 | 0.927 | ||

| Item 22 | 0.761 | 0.786 | ||

| Item 23 | 0.825 | 0.847 | ||

| Item 29 | 0.566 | 0.634 | ||

| Item 30 | 0.779 | 0.825 | ||

| Factor 4 | 2.344 | 9.66 | ||

| Item 24 | 0.666 | 0.706 | ||

| Item 25 | 0.871 | 0.893 | ||

| Item 26 | 0.831 | 0.864 | ||

| Item 27 | 0.773 | 0.812 | ||

Extraction method: principal component analysis.

The Cronbach's alpha value was determined to be 0.894. It was at a good level in terms of internal consistency and was close to perfect (Table 4).

Cronbach's alpha values of the factors.

| General | Split – half Cronbach's alpha | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Cronbach's alpha when items are deleted | Total item correlation | Cronbach's alpha value of factors | Part 1–Part 2 |

| Factor 1 | 0.974 | 0.936–0.964 | ||

| Item 1 | 0.762 | 0.974 | ||

| Item 2 | 0.720 | 0.975 | ||

| Item 3 | 0.782 | 0.973 | ||

| Item 4 | 0.815 | 0.973 | ||

| Item 5 | 0.879 | 0.972 | ||

| Item 6 | 0.892 | 0.971 | ||

| Item 7 | 0.840 | 0.972 | ||

| Item 8 | 0.792 | 0.973 | ||

| Item 9 | 0.920 | 0.971 | ||

| Item 10 | 0.877 | 0.972 | ||

| Item 11 | 0.913 | 0.971 | ||

| Item 12 | 0.921 | 0.971 | ||

| Item 13 | 0.858 | 0.972 | ||

| Item 19 | 0.883 | 0.972 | ||

| Factor 2 | 0.976 | 0.960–0.946 | ||

| Item 14 | 0.895 | 0.974 | ||

| Item 15 | 0.901 | 0.973 | ||

| Item 16 | 0.893 | 0.974 | ||

| Item 17 | 0.966 | 0.969 | ||

| Item 18 | 0.936 | 0.971 | ||

| Item 20 | 0.893 | 0.974 | ||

| Item 28 | 0.906 | 0.973 | ||

| Factor 3 | 0.881 | 0.837–0.849 | ||

| Item 21 | 0.661 | 0.868 | ||

| Item 22 | 0.751 | 0.848 | ||

| Item 23 | 0.584 | 0.885 | ||

| Item 29 | 0.824 | 0.828 | ||

| Item 30 | 0.781 | 0.839 | ||

| Factor 4 | 0.818 | 0.820–0.774 | ||

| Item 24 | 0.606 | 0.843 | ||

| Item 25 | 0.763 | 0.765 | ||

| Item 26 | 0.476 | 0.838 | ||

| Item 27 | 0.649 | 0.816 | ||

| General | 0.894 | 0.955–0.813 | 0.894 | 0.955–0.813 |

Reliability test.

The factor coefficient, which is one of the related questions for Factor 1, ranges from 0.150 to 0.065 (Table 5).

Coefficients of factor scores.

| Component score coefficient matrix | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | ||||

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | |

| Item 1 | 0.082 | −0.002 | 0.000 | −0.029 |

| Item 2 | 0.065 | −0.002 | 0.017 | 0.013 |

| Item 3 | 0.075 | 0.001 | 0.019 | −0.010 |

| Item 4 | 0.082 | −0.009 | −0.001 | −0.004 |

| Item 5 | 0.089 | −0.003 | −0.009 | −0.006 |

| Item 6 | 0.097 | −0.009 | −0.007 | −0.034 |

| Item 7 | 0.088 | −0.005 | −0.016 | −0.012 |

| Item 8 | 0.077 | 0.003 | −0.021 | 0.015 |

| Item 9 | 0.094 | 0.002 | −0.013 | −0.013 |

| Item 10 | 0.092 | −0.001 | −0.012 | −0.019 |

| Item 11 | 0.095 | −0.009 | −0.015 | −0.011 |

| Item 12 | 0.088 | 0.001 | 0.006 | −0.004 |

| Item 13 | 0.085 | −0.008 | −0.001 | −0.001 |

| Item 19 | 0.150 | −0.015 | 0.002 | 0.007 |

| Item 14 | −0.010 | 0.088 | −0.012 | 0.002 |

| Item 15 | −0.009 | 0.152 | −0.010 | −0.005 |

| Item 16 | −0.012 | 0.150 | −0.002 | 0.007 |

| Item 17 | −0.012 | 0.159 | 0.010 | −0.001 |

| Item 18 | −0.009 | 0.156 | 0.000 | −0.009 |

| Item 20 | −0.008 | 0.152 | 0.005 | −0.019 |

| Item 28 | −0.003 | 0.151 | 0.003 | −0.016 |

| Item 21 | −0.025 | 0.003 | 0.232 | −0.002 |

| Item 22 | −0.028 | −0.007 | 0.253 | −0.013 |

| Item 23 | −0.013 | 0.005 | 0.205 | −0.001 |

| Item 29 | −0.030 | 0.000 | 0.266 | −0.013 |

| Item 30 | −0.024 | 0.002 | 0.255 | −0.010 |

| Item 24 | −0.062 | −0.015 | 0.005 | 0.326 |

| Item 25 | −0.062 | −0.020 | −0.002 | 0.359 |

| Item 26 | −0.030 | 0.003 | −0.014 | 0.242 |

| Item 27 | −0.053 | −0.011 | −0.025 | 0.328 |

Extraction method: principal component analysis. Rotation method: equamax with Kaiser normalization.

Correlation coefficients were high in the test and retest relationships, indicating that they were correlated. The results showed that reliability was reproducible in terms of internal and external consistency (Table 6).

Test and retest correlation coefficients.

| (n=367) | r | p |

|---|---|---|

| Question 1 & Retest – Question 1 | 0.967 | <0.001 |

| Question 2 & Retest – Question 2 | 0.975 | <0.001 |

| Question 3 & Retest – Question 3 | 0.965 | <0.001 |

| Question 4 & Retest – Question 4 | 0.968 | <0.001 |

| Question 5 & Retest – Question 5 | 0.909 | <0.001 |

| Question 6 & Retest – Question 6 | 0.923 | <0.001 |

| Question 7 & Retest – Question 7 | 0.941 | <0.001 |

| Question 8 & Retest – Question 8 | 0.919 | <0.001 |

| Question 9 & Retest – Question 9 | 0.928 | <0.001 |

| Question 10 & Retest – Question 10 | 0.930 | <0.001 |

| Question 11 & Retest – Question 11 | 0.927 | <0.001 |

| Question 12 & Retest – Question 12 | 0.910 | <0.001 |

| Question 13 & Retest – Question 13 | 0.938 | <0.001 |

| Question 14 & Retest – Question 14 | 0.881 | <0.001 |

| Question 15 & Retest – Question 15 | 0.877 | <0.001 |

| Question 16 & Retest – Question 16 | 0.884 | <0.001 |

| Question 17 & Retest – Question 17 | 0.867 | <0.001 |

| Question 18 & Retest – Question 18 | 0.874 | <0.001 |

| Question 19 & Retest – Question 19 | 0.932 | <0.001 |

| Question 20 & Retest – Question 20 | 0.877 | <0.001 |

| Question 21 & Retest – Question 21 | 0.954 | <0.001 |

| Question 22 & Retest – Question 22 | 0.978 | <0.001 |

| Question 23 & Retest – Question 23 | 0.954 | <0.001 |

| Question 24 & Retest – Question 24 | 0.977 | <0.001 |

| Question 25 & Retest – Question 25 | 0.960 | <0.001 |

| Question 26 & Retest – Question 26 | 0.966 | <0.001 |

| Question 27 & Retest – Question 27 | 0.960 | <0.001 |

| Question 28 & Retest – Question 28 | 0.872 | <0.001 |

| Question 29 & Retest – Question 29 | 0.971 | <0.001 |

| Question 30 & Retest – Question 30 | 0.987 | <0.001 |

Paired samples correlations.

r: correlation coefficient.

In confirmatory factor analysis, Factor 1 ranged between 0.80 and 0.98, Factor 2 between 0.89 and 0.95, Factor 3 between 0.63 and 0.83, and Factor 4 between 0.75 and 0.92. In factor-equalization modeling, our model was found to be appropriate since 3 of the confirmatory fit indices were good and 4 of them were acceptable (Table 7).

Confirmatory factor analysis fit indeces.

| Index | Good fit | Acceptable | Application | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X2/df | Chi-square/degrees of freedom value | <3 | 3<(X2/df)<5 | 3.302 | Acceptable |

| RMSEA | Root mean square error of approximation | <0.05 | <0.08 | 0.057 | Acceptable |

| CFI | Comparative fit index | >0.95 | >0.90 | 0.998 | Good fit |

| NFI | Fix indeces | >0.95 | >0.90 | 0.998 | Good fit |

| NNFI (TLI) | Non-normed fix indeces (Tucker-Lewis index) | >0.95 | >0.90 | 0.789 | No fit |

| IFI | Incremental fit index | >0.95 | >0.90 | 0.998 | Good fit |

| GFI | Goodness of fit index | >0.90 | >0.85 | 0.849 | Acceptable |

| AGFI | Adjusted goodness of fit index | >0.90 | >0.85 | 0.854 | Acceptable |

Health education programs are recommended because of the alarmingly high levels of insufficient information, negative distorted attitudes, and malpractice related to the COVID-19 pandemic in a survey study.18 One study stated that the possibility of control decreases with the increase of transmission of COVID-19 prior to symptoms beginning. It is stated that models are needed to reflect updated transmission characteristics and more specific definitions of epidemic control.19 As states that in these studies, deficiencies in knowledge, education, attitude, behavior, and detecting mistakes are not sufficient in pandemics or other serious situations. These results highlight the importance of scale development in our study. In extraordinary situations such as pandemics, in addition to identifying the situation and problem, there is a need for attitude and behavioral awareness. Our results revealed that positive guidance was provided to individuals to improve attitudes and behaviors in COVID-19 and similar pandemics.

Many adults with comorbid conditions did not have critical knowledge of COVID-19 and did not change their routines or plans despite their concerns. This inequality suggests that more public health efforts may be needed to mobilize the most vulnerable communities.20 More research is needed to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and to evaluate the effectiveness of the measures taken. Responsiveness is crucial to discourage negative health-seeking behaviors and to encourage positive preventive and therapeutic practices for fear of increased mortality.21 In a study in China, participants had good knowledge, positive attitude, and active practice about COVID-19, but the results recommended strengthening nationwide promotion and focus on the uneducated population.22

Situations accompanied by chronic diseases, vulnerable populations, and nationwide decisions suggest the need for a real and reliable identification of the problem, as in these studies. The need for effective scales in these studies also supports the necessity of our study.

Lack of knowledge of appropriate control methods can exacerbate racial and ethnic disparities. Additional research is needed to identify reliable sources of information and disseminate accurate prevention and treatment information.23

It is important to note that additional research is needed after this study, and that methods with a specific scope and content are recommended in research.

Today, younger and healthier populations are affected more than ever before. In the absence of any specific therapeutic agent, such as coronavirus infections, the most effective individual preventative measure is knowledge. This is a time to introspect and learn from our mistakes. Countries need to act urgently in this and similar situations.24

To our knowledge, this scale is the only scale developed regarding knowledge, attitudes and behaviors about COVID-19 in Turkey and in the world. The scale questions in our study will set an example in terms of providing a systematic approach to the problem in COVID-19 and similar pandemics by raising awareness on both physicians and individuals on a scientific basis. The scale will guide the researches during the COVID-19 process and in similar pandemics that may develop thereafter.

Strengths and limitationsTo our knowledge, this scale is the first scale developed regarding knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding COVID-19 in Turkey and in the world. The scale will guide researches during the COVID-19 process and in probable future pandemics. This fact will positively contribute to the well-being and health status of people all around the World. Besides these strengths, our study has a limitation of including participants from only one country, namely Turkey. For that reason, it should be developed for other countries by taking into account the health conditions of them, before it can be used as a worldwide scale.

ConclusionThe valid and reliable Turkey COVID-19 Attitude Scale, which we developed to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes and behaviors of individuals about COVID-19, will guide research in the COVID-19 process and future pandemics.

- •

Since the beginning of the pandemic, studies have been carried out on the information, attitudes and behaviors of individuals and societies against Covid-19. However, the pandemic is not over yet and even tends to increase due to variants.

- •

This scale is the only scale developed regarding knowledge, attitudes and behaviors about COVID-19 in Turkey and in the world. The scale will guide the researches during the COVID-19 process and in similar pandemics that may develop thereafter.

OG, CE conceived, designed, and completed statistical analysis & editing of manuscript.

OG, CE completed data collection and manuscript writing.

OG completed review and final approval of manuscript.

DisclaimerNone.

Source of fundingNone.

Conflict of interestNone.

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.