Introduction

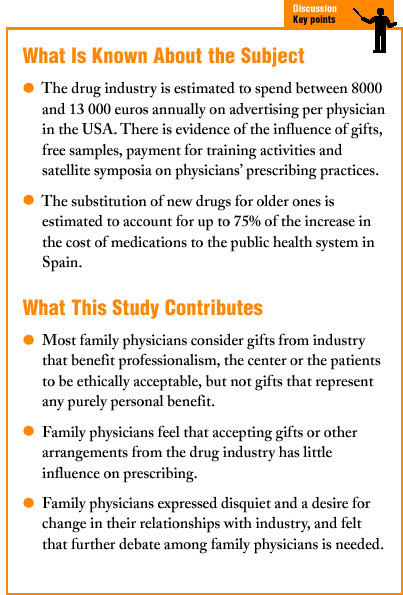

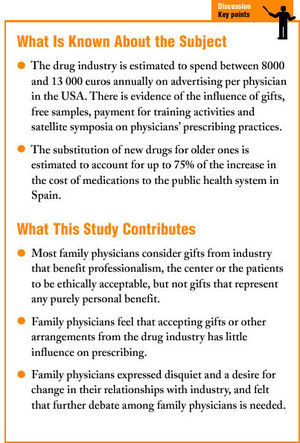

Few topics in medicine generate as much controversy as the relationship between practitioners of medicine and the drug industry. Pharmaceutical companies spend approximately 39% of their budget on marketing efforts, an amount that has direct repercussions on the price of their products1 It is estimated that in the USA, the drug industry spends between 8000 and 13 000 euros annually on advertising per physician2,3 Moreover, the substitution of newer drugs for familiar, safe products is estimated to account for as much as 75% of the increase in the cost of medications to the public health care system in Spain4

Drug prescribing should be based on available scientific criteria and on ethical principals of nonmalfeasance (doing no harm), benefit, fairness and independence. Scientific evidence is the main criterion available to guarantee nonmalfeasance, benefit and fairness. Appropriate prescribing should seek to achieve maximal effectiveness, minimum risk to the patient, minimal cost, and respect for the patient´s choice. Despite these considerations, the most readily available source of drug information to the family physician is currently the drug industry itself. The economic resources spent by the industry on advertising its products in the lay press, mail campaigns, advertising in journals and other media, and on direct inducements aimed at professionals, explains part of their influence on prescribing practices.

A number of studies have analyzed physicians' perceptions of the relationships established with drug companies and the ethical problems that can arise from these relations; however, none of these studies was done in Spain5-16 In 2003 the Ethics Group of the Catalonian Society of Family and Community Medicine (SCMFiC) published a document that offered some reflections, from an ethical standpoint, on primary care physicians' relationship with the drug industry17 The present study was carried out to document the opinions of members of the SCMFiC regarding individual relations with the drug industry, considerations on the ethics of accepting gifts or other arrangements from industry, and views on the possible influence of these arrangements on prescribing practices.

Material and Methods

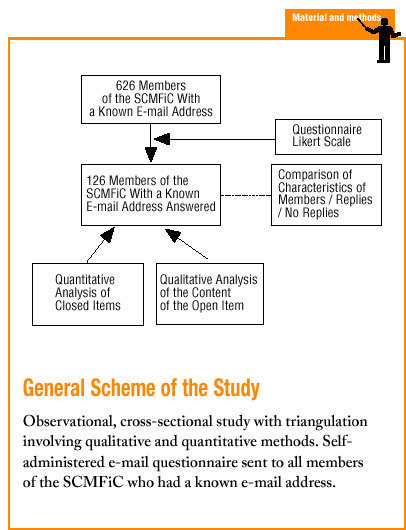

A cross-sectional, observational study was designed with triangulation, involving quantitative and qualitative methods. The results were enhanced by the way in which these three approaches complemented each other.

During the month of June 2002 all members of the SCMFiC with a known e-mail address were sent a questionnaire by e-mail regarding relationships with the drug industry. Of the 2521 members, 626 had a known e-mail address. Considering the usual rate of response for this type of postal or e-mail survey, we hoped to receive at least 95 responses, a number which would have allowed us to estimate 50% agreement with "acceptance of financial support from industry for training" with an alpha error of 0.05, a beta error of 0.20 and a precision of 0.10. Because the subject of the survey was considered sensitive, we did not resend the questionnaire or use telephone reminders to encourage participants to complete and return it. We also considered it inappropriate to use incentives for participation. A pilot study was done previously in a subgroup of SCMFiC members.

The questionnaire (annex available as supplementary material on line) asked participants to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement on a Likert scale with the ethicality of accepting different types of gifts offered by industry, and their perceptions of how these gifts influenced their prescribing practices. An open-ended item was included to solicit the participants´ views about the topic in general.

Triangulation was used to analyze the responses: a quantitative approach for closed items, and a qualitative approach for text content produced in response to the open-ended item. Textual data were analyzed with the Atlas-ti program, which segmented texts into 27 codes that emerged from the discourse.

The survey formed part of ongoing research by the Ethics Group of the SCMFiC,17 and priority was given to dissemination of the questionnaire to as many members as possible rather than to achieving a representative sample. Because of the interest of the results, we decided to prepare a manuscript for publication. Before the manuscript was submitted, we requested authorization from all participants.

Results

Quantitative Results

Of the 626 questionnaires sent, responses were received from a total of 162 members (25.9%), and of this number, 49 persons responded to the open-ended item. We excluded 25 questionnaires as incomplete. Therefore the quantitative results reported here reflect data from 137 questionnaires, and the qualitative results reflect text-based responses from 49 participants. As shown in Table 1, mean age of the members who responded to the survey was 39.6 years (34.92 years for all members) and 45.3% were men (29.5% for all members).

Detailed results are presented in Tables 2 and 3. The types of gifts and arrangements that the largest percentage of family physicians considered ethically acceptable were publicity items (82.5%), free drug samples (78.1%) and payment of registration fees for congresses or workshops (74.3%). In contrast, only 3 physicians considered it ethical to accept direct economic compensation in exchange for prescribing a certain number of packages of a drug (2.2%). An intermediate percentage of persons considered it ethical to accept a free dinner (40.1%) or a weekend trip to a pleasant destination (20.6%).

With regard to the possible influence of different types of gifts and other arrangements, we note that the highest percentages of respondents indicated that prescribing was likely to be influenced by direct economic compensation in exchange for prescribing a given product (38.3%), followed by payment of travel expenses (35.8%) and the donation of material for the center (35%). The type of gift the lowest percentage of participants judged likely to influence prescribing was publicity items (10.9%).

Qualitative Results

Ethical considerations of family physicians regarding their relationship with the drug industry. In general, informants considered their relationship with industry to be ethically acceptable when the results were beneficial and had favorable repercussions on professionalism, the center and their patients, but not when the physician obtained any purely personal benefit from the relationship. Nonetheless, even when the aim was to benefit professionalism, the center or the patients, the relationship was not considered ethical if the prescribing physician committed to prescribing certain products and changed his or her prescribing practices. Table 4 lists some of the comments participants offered in response to this item.

Although many professionals have particular conceptions as to what is ethical and what is unethical in their relationship with industry, it was noteworthy that several participants maintained a relationship they did not like and that led to conflicts, and sought arguments to justify their ambiguous position (R28 and R35 in Table 4).

Further indications of ambivalence toward these relationships were the annoyance and suppressed rage reflected in some responses, and the fact that some participants perceived certain items to call into question current relationships between family physicians and the drug industry while failing to raise similar questions about the attitudes of other collectives and institutions. Examples of this view are shown in table 4, R21 and R36.

These findings lead us to think that there is unease and a desire for change among the collective of family physicians regarding their relationship with industry. These attitudes crystallized in a call for more debate on this issue. Some participants expressed a wish for this debate to examine the issue realistically (Table 4, R32, R34, and R11).

Opinion regarding industry involvement in training. Most comments in response to the open-ended item made reference to industry participation in training for family physicians. The number of responses and the intensity of emotion they reflected showed that this was the topic professionals were most concerned about. Our informants felt that training is necessary but the high cost of training activities makes them unaffordable unless they are sponsored. For this reason, and because of the lack of other sources of financing, many felt that industry participation in training activities was appropriate (Table 5, R18).

Many informants accepted industry participation in training, but wished things were different and felt that costs should come down, or that other entities should assume responsibility for sponsoring training events (Table 5, R37).

Many opinions reflected the view that health service firms had ceased to organize training activities for their professional staff. These responses reflected the belief that if the health service firms assumed responsibility for training, this might change the relationship with industry (Table 5, R03 and R02).

A few informants questioned the need for industry involvement in training, and mentioned the need for quality surveillance for training activities, suggesting that quality was not guaranteed when training was left in the hands of industry (Table 5, R17).

Opinion regarding leisure-time activities and gifts offered by the drug industry, and regarding economic compensation in exchange for prescriptions. Some persons did not consider it ethical to accept gifts, and distinguished clearly in terms of ethicality between accepting gifts and accepting financial support for training events. Others considered ethicality to depend on the value and type of gift and the degree of the prescriber's commitment to the industry. Table 6 lists some of the responses regarding this issue.

Some informants noted that accepting gifts allowed family physicians to accord themselves the status they felt they deserved but lacked (Table 6, R37).

Participants considered economic compensation in exchange for a commitment to prescribe the company's products as bribery, and as ethically unacceptable. Some professionals had received offers of this type but had declined them (Table 6, R44).

Opinion of family physicians regarding the influence of the type of relationship with the drug industry on prescribing. Several colleagues were convinced that the relationship with industry influenced prescribing. Their concern over this issue led them to reject all offers of gifts or other arrangements from pharmaceutical firms (Table 7).

Other participants, in contrast, believed themselves to be uninfluenced by their relationship with industry and even by the acceptance of gifts. If they admitted to being influenced by gifts, they felt it was appropriate to give something to the drug firm in return (Table 7, R18 and R29).

Some felt that the influence could be avoided if the professional's attitude toward the drug industry was clear-cut. Among the strategies they noted to avoid influence were 1) making the bounds of their commitment clear before accepting financial support; 2) diversifying the sources of financial support among different drug companies; and 3) refusing individual negotiations in favor of institution-based negotiations (Table 7, R38 and R02).

Discussion

The ethicality of physicians' relationships with industry is a highly current topic that causes concern among members of the SCMFiC and creates dissonance between professionals' opinions and the scientific evidence.

One important limitation of this study is concerned with external validity. The results of this study are not representative of all members of the SCMFiC, but nonetheless are important, we feel, because they reflect the opinions of one sector of the membership. In addition, the findings provide some knowledge of physicians' attitudes, a subject that has previously remained unstudied among family physicians in Spain.

The selection bias caused by surveying only those members with a known e-mail address and by the low response rate led to overrepresentation of older family physicians and men (Table 1), and probably of members who belong to working groups and who are among the more active members of the society. Overrepresentation of these members is important, especially if we recall that a Canadian study found that it was younger residents who considered it ethical to accept gifts from industry.12 However, we feel that the most important limitation of our study is the low response rate, despite the fact that this survey attained the highest response rate of all SCMFiC e-mail surveys to date.

Self-administered questionnaires distributed by e-mail have a number of well-known advantages (low cost and availability to larger numbers of respondents), but their main drawback is their low response rate compared to other types of survey18,19. An analysis of the selection bias and nonresponse bias in our study suggests that our participants were mainly those professionals whose awareness of the issue and motivation to respond were greatest. Our results therefore reflect the views of professionals who have spent some time reflecting upon their relationships with industry.

A majority of informants considered it ethical to accept publicity items, free drug samples and financial support for training. In contrast, most considered it unethical to accept a free dinner, an expense-paid trip, or direct economic compensation in return for prescribing a certain drug. Nonetheless, a nonnegligible percentage of participants considered it ethical to accept these latter types of gifts, despite the fact that they are illegal. In this connection current Spanish law regarding prescription drugs expressly prohibits health professionals involved in prescribing from accepting any direct or indirect offer of any incentive, reward or gift from persons with any direct or indirect interest in the production, manufacture and sale of drugs20. Our qualitative findings reveal that the discrepancies between attitudes and practices arise mainly from the belief that it is ethical to accept gifts that benefit professionalism, the center or the patients, but not gifts that involve any personal benefit to the physician.

Perhaps the most noteworthy of our findings is that despite evidence to the contrary, the percentage of members who believed that accepting gifts or other arrangements influenced their prescribing practices was low.21 The highest percentage of persons who considered gifts to influence their prescribing associated this influence with direct payment in exchange for prescribing a certain product, payment of travel expenses, material donated to the workplace, and financial support for training. Interestingly, few participants felt that accepting a free dinner influenced their prescribing practices. In this connection, earlier studies showed conclusively that the gifts that influence prescribing most strongly are donations of free samples, continuing medical education events paid for by industry, and financial support for trips to conferences and meetings.14,21 Other studies have also reported that physicians underestimate the influence of industry on prescribing. A Canadian study found that of 200 authors who participated in the writing of clinical practice guidelines, 87% admitted to financial ties with the drug industry, and 93% stated that these ties did not affect their recommendations in the guidelines. However, they felt that such ties did influence their colleagues.16 Patients, in contrast, perceived relationships with the drug industry to have a clear influence on prescriptions written by their physician: 70% felt that gifts influenced prescribing, and 64% felt that these gifts increased the cost of medication22. Patients felt it was acceptable for drug sales representatives to give physicians free samples, but not to pay for a meal, cover travel expenses, or give them infant formulas for their children.

Two further elements stood out in our analysis of the comments in response to the open-ended questionnaire item. Several respondents called for efforts to stimulate debate regarding the relationships between family physicians and the drug industry, and urged colleagues to initiate such a debate. In addition, participants noted the unease and ambivalence among members of this collective with regard to their relationships with the drug industry.