The basis of advance health care directives (AHCD) is the respect and promotion of personal freedom. The content of this law, due to its sensitivity and importance, should beg a question to organisations and doctors: Do we have the challenge to develop an active role from the field of primary care? I believe we have.

Let´s look at some of the evidence.

The concept of advance directives is more than just legal considerations and is, in the health environment, an advanced expression of the freedom of choice of people which determines the freedom to accept or reject certain medical treatments according to the life circumstances and personal values.

Social progress seen as favourable by the population within the framework of well-being fosters the freedom of choice in doctor-patient shared decisions, overcoming the paternalistic attitudes of doctors, as well as the perceptions of the state as supreme guardian of the interests of individuals.1 As mentioned in the study, 36 289 people in Spain have filled in their AD document. Without a doubt it is an interesting path, but experts like the late David Thomasma stated that "The living will is only effective within a close clinical relationship" (DM, May 25, 2001). All an integral process of participation within the framework of advance decision planning, which the authors of the study point out.

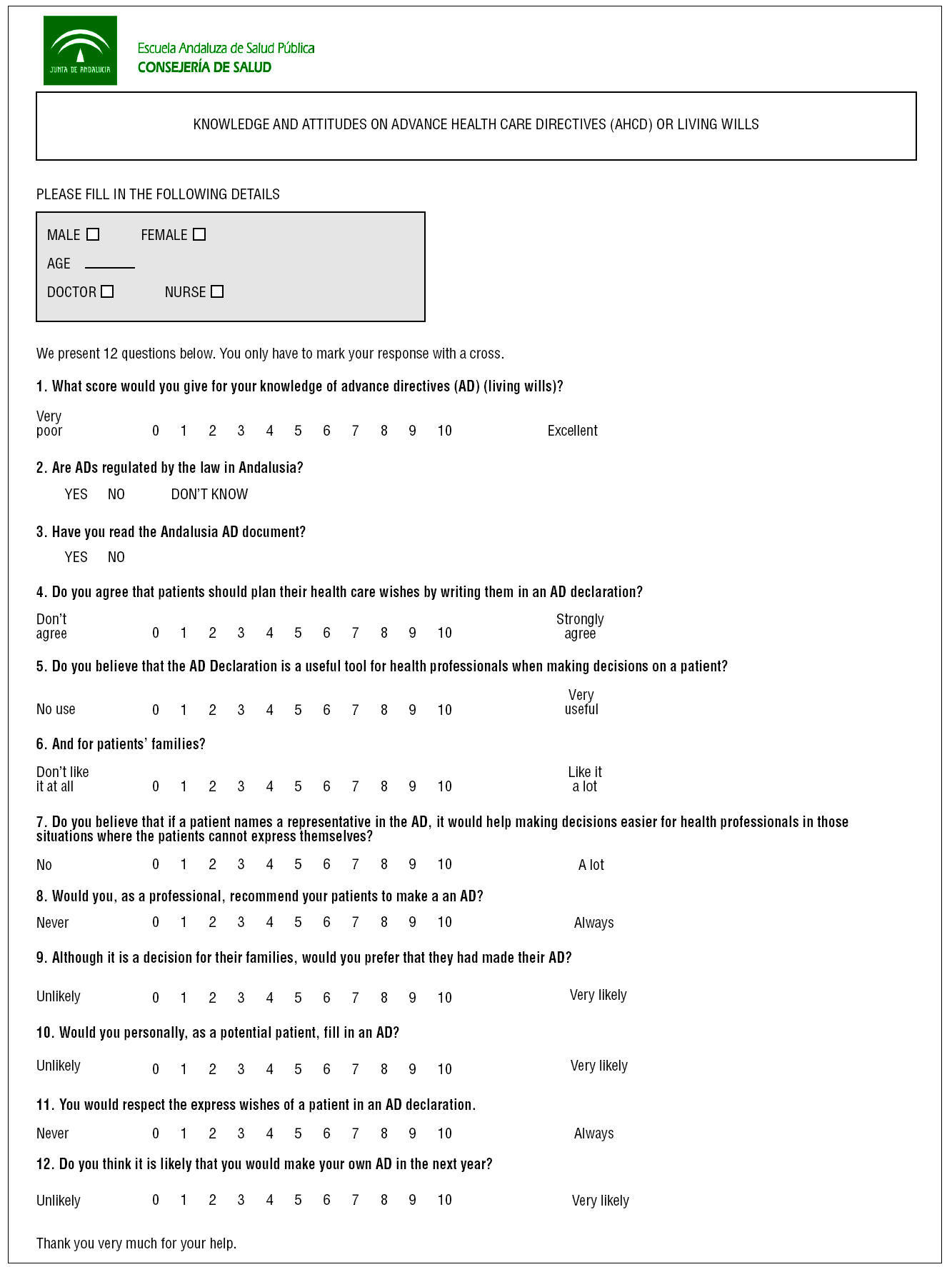

Therefore, to examine the knowledge and attitudes doctors and health professionals to establish the improvements necessary to guarantee the use of this right of the people, should be a prime objective as a first step to planning concrete strategies in our health centres.

For the people, to be faced with death is an important maturing process which helps to make doctor-patient communication more effective.

When? At any time, everyone chooses their own.

Paraphrasing Jean de la Bruyère: "Death comes but only once but it is felt all throughout life."

Relevance of the Study

It could not be more useful to consider the media and social impact of the voluntary deaths of Sampedro, Jorge León, Madelein Z, and the case of Inmaculada Echevarría. A digital search introducing these names finds sufficient titles, opinions, and expert analyses, by professional bodies, associations for the chronically ill, citizens associations, ethics committees, legal advisory councils, ministries and ministers, which on the whole could be considered as the best evidence available so that the doctors may become acquainted with it in their practices, where the right of the patient to limit the therapeutic effort is legal and ethically correct.

The communication media have saturated society with public, real, practical, and useful knowledge, of the laws that enable the principle of autonomy to be developed in health care practice.

The social debate that arose from the case of Inmaculada Echevarría on the right to a dignified death goes towards "normalising" the effective palliative solutions that limit the therapeutic effort respecting the will of the people.

Thus it would be easier to make decisions that respect the previous instructions and that doctors and the population "are felt to be" within the current laws and good clinical practice.

The People

People are not reluctant to talk about death and, in my experience--"community forum" (70 people) and focal group activity--, demonstrated, naturally, that they would like to express their advanced directives to the doctors, and their main concern is to receive effective palliative care.2

The ethical and legal dilemmas are also a daily reality in primary care, care in the terminal stages and care in the dying process, when the patient and family have decided that it happens at home, increasingly places the doctors in difficult situations. To collect, at the appropriate time, someone´s AD as one more page in the clinical history in our daily routine would make subsequent clinical decisions much easier, both for professionals and families.

The Professionals

The qualitative results of an investigation with 209 health professionals from 16 health centres3 were able to conclude that the rejection attitudes were very uncommon, and a clear majority of professionals were in favour of

using a living will in the clinical history as one work tool more.

However, difficulties are often pointed out when personally confronted with patients to talk about the subject of death and, therefore, to obtain an AD.

This could explain the contradiction found in the study between the theoretical willingness and the real possibilities of complying with an advance directive document by the professionals.

The expression of an AD must be based on a prospective and confident doctor patient relationship, it would be an implicit agreement, contained in conversations, effective communication, with periodic follow-up and recorded in the clinical history, more than a document, which could also be effective, when it is thus decided the patient is well informed.

The professionals, besides having knowledge on AD, should inform the patients, perhaps prioritising by risk, on their favourable attitude to personalise certain aspects, according to clinical situations, in the contents of the advance directive document.

The Response to the Initial Tentative Question

Primary care should actively participate in spreading awareness of these rights, fostering in the clinics, "that every citizen who wishes it, and at a time they consider appropriate, may express their feelings, their concerns, their will, on the medical care they would like to receive, or not receive, at the end of their life."

Just like a record in the clinical history and/or an advance directive document, each citizen decides, no more no less.

Material para internet

Key Points

• The social evolution felt by the citizens is overcoming the paternalistic attitudes of health care professionals, as well as the conceptions of the state as supreme guardian of the interests of the individual.

• The bases of advance directives are the respect and promotion of the freedom of the person. Do we accept the challenge to play an active role from primary care?

• "That every citizen who wishes it, and at a time they consider appropriate, may express their feelings, their concerns, their will, on the medical care they would like to receive, or not receive, at the end of their life."