Frailty is associated with an increased morbidity and mortality among patients with cirrhosis. However, no specific treatment strategy has been formally recommended for these patients. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a strategy based on exercise and nutritional intervention improving frailty in cirrhotic patients listed for transplantation.

Patients and MethodsPatients with increased Liver Frailty Index (LFI) (≥3.2) were randomized to a control group (standard exercise and nutritional counseling) or intervention group (guided by physical therapist and dietitian) for 12 weeks, LFI was measured, and patients were classified as frail or prefrail. The change in LFI was assessed at the end of study.

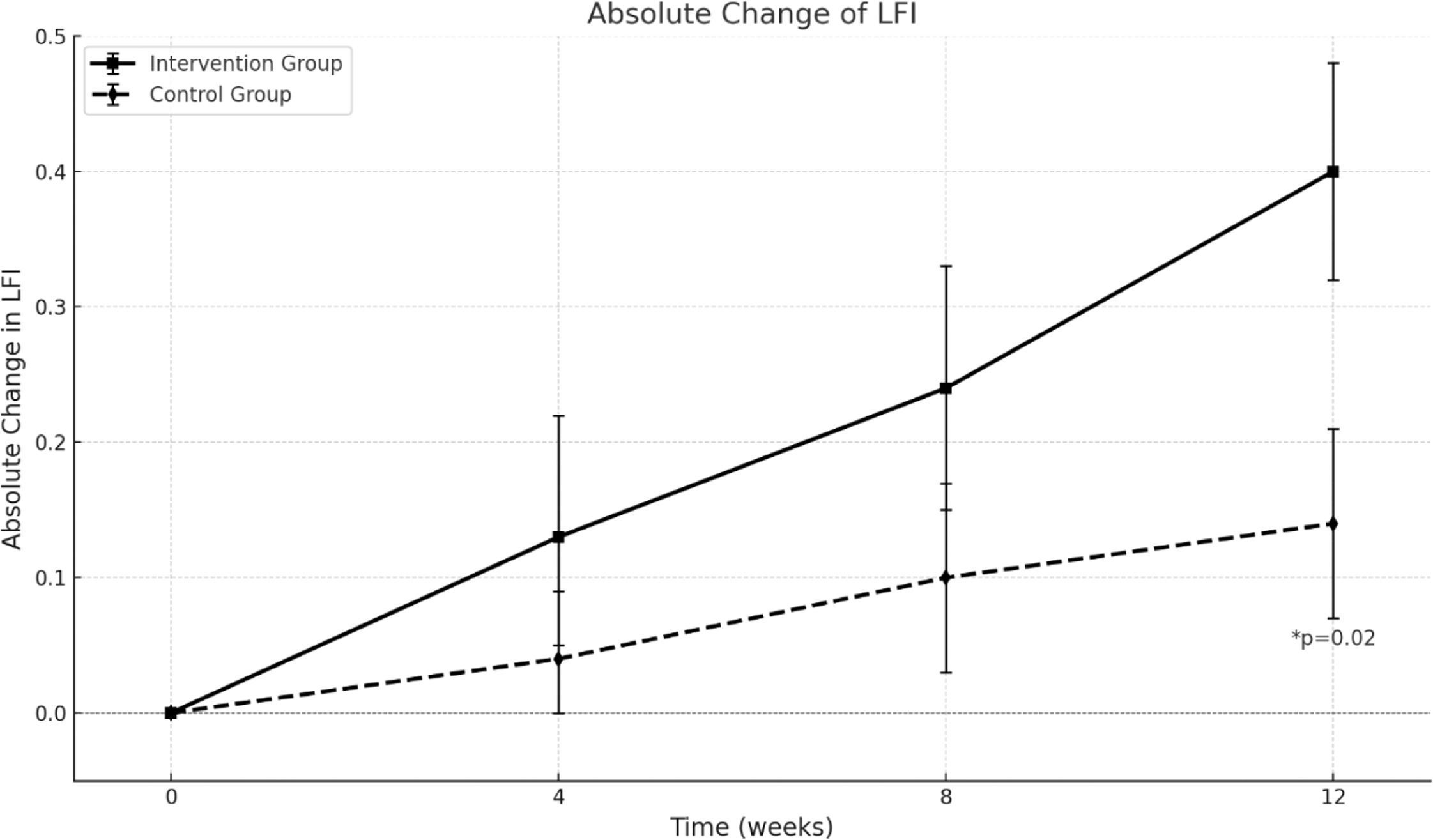

ResultsSixty-six patients were included (34 to the control group and 32 to the intervention group), age 59.3 ± 8.8, male 51.5 %, main etiologies: MASLD (40.9 %), ALD (15.2 %), MetALD (6.1 %), PBC (6.1 %), autoimmune hepatitis (4.5 %), MELD Na 17.2 ± 5, Child Pugh A/B/C 13.6 %/57.6 %/28.8 %, Na 137±3 mEq/L, creatinine 0.8 ± 0.3 mg/dL, bilirubin 3.3 ± 3 mg/dL, INR 1.5 ± 0.4, albumin 3.3 ± 0.5 g/dL, LFI 4.23 ± 0.5, frail/prefrail (%) 34.8/65.2. There was a significant improvement in LFI at the end of the study in the intervention group (ΔLFI 0.4 vs ΔLFI 0.14, p = 0.02). Notably, we found a significant reduction in the proportion of frail patients in the intervention group vs control group (28.1 % vs 8.8 %, p = 0.02) at the end of the study.

ConclusionsThis randomized controlled trial conducted in patients listed for liver transplantation demonstrates that a dual intervention can effectively reduce frailty in this population.

Cirrhosis significantly impairs quality of life, affecting over 120 million people worldwide causing about two million deaths annually and ranking as the 15th leading cause of disability-adjusted life years. [1].

The most significant manifestations of cirrhosis are primarily related to the development of liver failure, complications arising from portal hypertension and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [2,3]. Although several tools are available to predict the prognosis of patients with cirrhosis, they are not able to accurately predict prognosis in some patients [4,5]. Consequently, frailty has been recognized as a distinct manifestation of cirrhosis, and significant efforts have been made to clarify its pathogenesis, definition, prognostic implications, and potential treatments [6].

Frailty is a multidimensional syndrome initially identified in the geriatric population, characterized by reduced physiological reserve and increased vulnerability to health stressors, which are independently associated with adverse outcomes [7]. In patients with cirrhosis its prevalence ranges from 18 %−43 % depending on the severity of liver disease, comorbidities and the diagnostic tool used [8]. Various tools have been developed to assess frailty, with the Liver Frailty Index (LFI) being extensively validated in this population. A LFI ≥3.2 is considered abnormal, categorizing patients as pre-frail with scores between 3.2 and 4.4, and frail if the score is ≥4.5 [9]. In a recent study, Wang et al. demonstrated that frailty (defined as an LFI score ≥4.5) was associated with an increased risk of mortality (HR 2.45; 95 % CI, 1.14–5.29) and hospitalization (HR 2.32; 95 % CI, 1.13–4.79), even among patients with compensated cirrhosis [10]. In a large multicenter study, an LFI score ≥4.5 was associated with an 82 % increased risk of waitlist mortality among patients listed for liver transplantation (LT), independent of the MELD-Na score, presence of ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy [11]. During time on the LT waitlist, approximately 50 % of candidates may experience worsening in their LFI score. Notably, an increase in LFI of ≥0.1 over 3 months has been linked to a twofold increase in the risk of waitlist mortality [12].

The main drivers of physical frailty are malnutrition, immobility, and sarcopenia, with additional influences from mental health, comorbidities, aging, cognitive decline, and socioeconomic or environmental factors [13].

Jamali et al. reviewed 11 randomized trials (358 participants) on nutritional and physical interventions for frailty. While results varied, several studies reported improved physical fitness, muscle strength, and quality of life [14,15] However, the effectiveness of combined interventions remains scarcely explored.

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of a simultaneous strategy based on a nutritional intervention and physical exercise in cirrhotic patients, as assessed by the Liver Frailty Index.

2Patients and Methods2.1PatientsPatients listed for liver transplantation at the Liver Transplant Unit (Hospital Clínico UCChristus) and evaluated as outpatients were recruited. Inclusion criteria were: 1) cirrhosis diagnosed via imaging or biopsy, 2) LFI ≥3.2 (pre-frail or frail), 3) ability to follow instructions, and 4) signed informed consent.

Exclusion criteria included: 1) hepatic encephalopathy grade 3 or 4, 2) prior liver transplantation, 3) inability to walk, 4) severe extrahepatic conditions limiting mobility (e.g., neurologic, neuromuscular, or skeletal disorders), 5) severe cardiac, renal, or pulmonary disease, 6) planned living donor liver transplantation within 12 weeks, 7) hospitalization within the previous 30 days and 8) hepatocellular carcinoma exceeding Milan Criteria.

2.2Study designRecruited patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to one of two arms:

a. Control Group: Patients followed standard recommendations, including unsupervised physical exercise or walking at least three times weekly. Compensated patients were advised to achieve 5.000 steps/day if possible. Nutritional guidelines included seven meals daily (including a late snack), incorporating meat, poultry, fish, and vegetables. Carbohydrates were adjusted for diabetes, and salt and water intake were restricted following hepatologist instructions.

b. Intervention Group: Patients were instructed to perform supervised physical therapy sessions, performing moderate-intensity exercise (50–60 % heart rate reserve or a Borg rating of perceived exertion of 5–6/10 for beta-blocked patients) 2–3 times weekly. Sessions included 20–30 min of aerobic activity and muscle strengthening for the upper and lower extremities. Home-based exercises were recommended if patients could not attend scheduled sessions which were registered for the investigators. A dietitian from the liver transplant program evaluated each patient every four weeks. All diets included seven daily meals (with a late snack) and 1.2–1.5 g protein/kg/day. Dietary caloric intake was tailored as follows:

- a.

Compensated cirrhosis: 30 kcal/kg/day

- b.

Decompensated/malnourished: 35–40 kcal/kg/day

- c.

Obese patients: 25–30 kcal/kg/day

One of the main differences among both groups was the periodic evaluation by a dietitian and a physical therapist to guide patients, clarify doubts, adjust available meals to match the recommendations and to ensure that the instructions were properly followed.

For a more detailed description of the physical and the nutritional indications for each group see supplementary material 1 and 2 respectively.

2.3Study design and outcomesThe 12-week study involved patient evaluations at baseline and every four weeks until completion. Besides, patients were called every two weeks to reinforce compliance. At each visit, LFI, gait speed (reduced if ≤0.8 m/s), and anthropometric measures were assessed. Quality of life, using the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), was evaluated at baseline and the final visit.

2.4Randomization and enrollmentPatients were randomized using a generated list of numbers by an independent, blind investigator who was not involved in treatment assignment or evaluations. Enrollment was conducted by the principal investigator.

2.5Data collectionAdditional variables registered included liver function tests, creatinine, serum sodium and potassium, albumin, blood count, Child-Pugh score, MELD-Na, and the presence of hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, hepatocellular carcinoma, diabetes, hypertension, and liver disease etiology.

The primary outcome of the study was a statistically significant change in LFI (delta LFI) after 12 weeks of follow-up compared to baseline.

The secondary outcome was a significant reduction in the proportion of frail patients in the intervention group compared to the control group defined as a LFI ≤3.2 at the end of the study among those classified as frail at baseline.

Another secondary outcome was an improvement on LFI ≥0.3 points as it was deemed clinically significant based on existing literature. Variables associated with LFI improvement were analyzed, and multivariate analysis was conducted to identify independent predictors.

Importantly, the evaluators and adjudicators were blinded to the group assignments of the patients.

2.6Adherence assessmentAdherence to the protocol was assessed employing an in-house questionnaire asking patients to rate their compliance with dietary and physical therapy instructions separately, using the following options: 1. Always, 2. Most of the time, 3. A good part of the time, 4. Sometimes, 5. A few times, 6. Almost never, 7. Never. Patients who reported following instructions at least “A good part of the time” were classified as having satisfactory adherence (see supplementary material 3).

Additionally, patients were asked to report the number of physical therapy sessions they completed during the 12-week follow-up period.

A dietary recall was conducted in each group to assess adherence to the initial nutritional recommendations.

2.7Sample size and statistical analysisBased on prior studies, the LFI in each group was assumed to follow a normal distribution with a standard deviation of 0.6. To detect a true mean difference of 0.5 points in LFI between the intervention and control groups, with 90 % power and a Type I error of 0.05, a sample size of 31 patients per group was required.

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using the Student's t-test. Categorical variables were analyzed with the chi-square test. A multivariate logistic regression model (binary logistic regression) identified variables independently associated with an LFI improvement of ≥0.3 points and frailty reversal, defined as an LFI <3.2 at the end of study. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp.).

2.8Ethical statementWritten informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study adhered to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (ID 220,111,001). All data were anonymized.

The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06149026).

3ResultsPatients were recruited between June 2022 and December 2023. A total of 92 patients were evaluated, but 12 were excluded due to being classified as robust, undergoing transplantation, hospitalization shortly after enrollment and before the start of study, loss to follow-up, or death. Ultimately, 34 patients were assigned to the control group and 32 to the intervention group (Fig. 1).

Of the recruited patients, 51 % were male, with a mean age of 59±8.8 years, a mean BMI of 28.0 ± 5, and a mean Liver Frailty Index (LFI) of 4.23±0.57. The primary etiologies were Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD, 40.9 %), alcoholic liver disease (ALD, 15.2 %), Metabolic and Alcoholic Liver Disease (MetALD, 6.1 %), autoimmune hepatitis (AIH, 4.5 %), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC, 6.1 %), and overlap syndrome (AIH/CBP, 6.1 %).

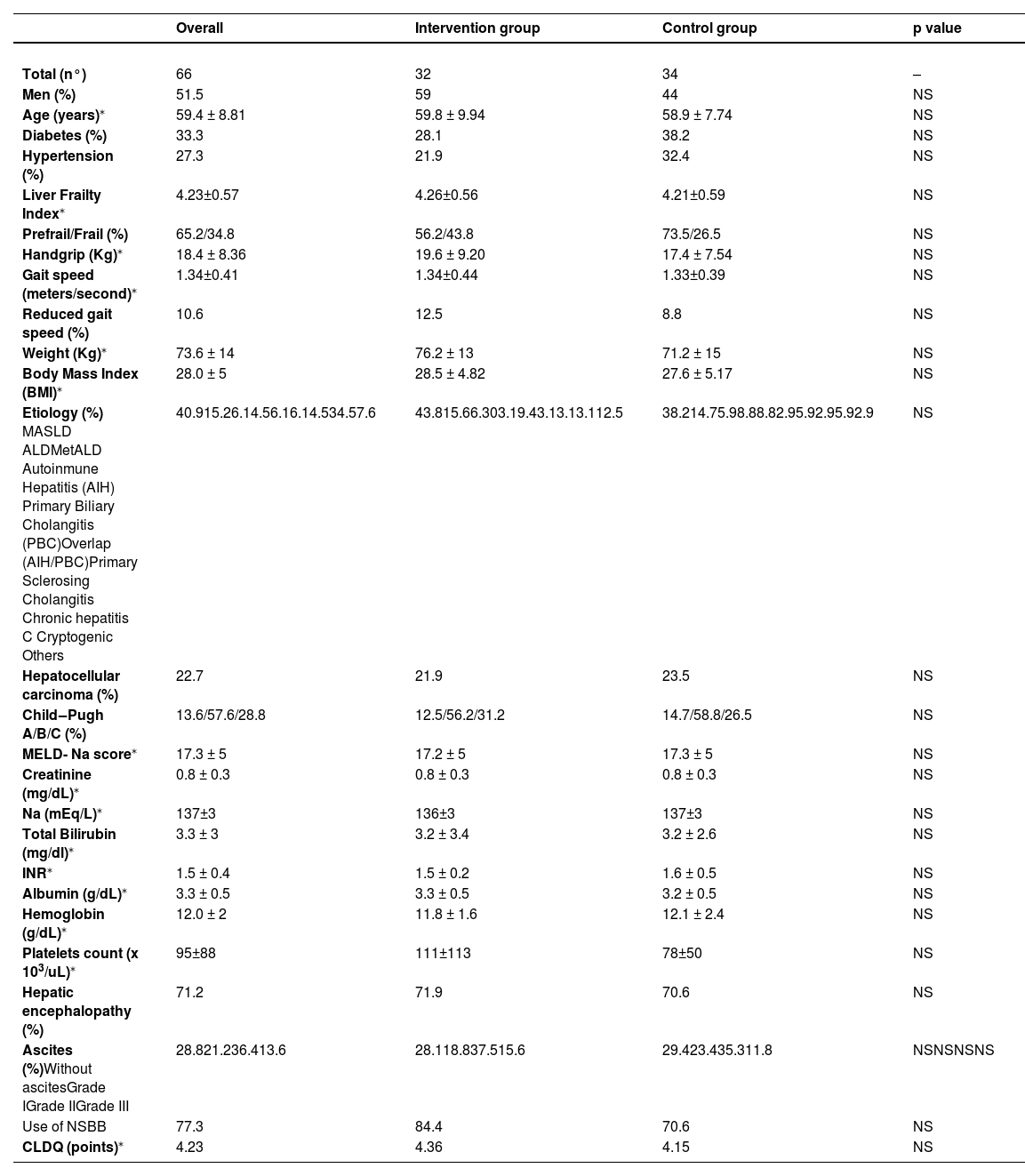

The mean MELD-Na score was 17.3 ± 5, with Child‒Pugh A/B/C classifications of 13.6 %, 57.6 %, and 28.8 %, respectively. Quality of life, as assessed by the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), was similar in both groups (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics of patients.

| Overall | Intervention group | Control group | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n°) | 66 | 32 | 34 | – |

| Men (%) | 51.5 | 59 | 44 | NS |

| Age (years)⁎ | 59.4 ± 8.81 | 59.8 ± 9.94 | 58.9 ± 7.74 | NS |

| Diabetes (%) | 33.3 | 28.1 | 38.2 | NS |

| Hypertension (%) | 27.3 | 21.9 | 32.4 | NS |

| Liver Frailty Index⁎ | 4.23±0.57 | 4.26±0.56 | 4.21±0.59 | NS |

| Prefrail/Frail (%) | 65.2/34.8 | 56.2/43.8 | 73.5/26.5 | NS |

| Handgrip (Kg)⁎ | 18.4 ± 8.36 | 19.6 ± 9.20 | 17.4 ± 7.54 | NS |

| Gait speed (meters/second)⁎ | 1.34±0.41 | 1.34±0.44 | 1.33±0.39 | NS |

| Reduced gait speed (%) | 10.6 | 12.5 | 8.8 | NS |

| Weight (Kg)⁎ | 73.6 ± 14 | 76.2 ± 13 | 71.2 ± 15 | NS |

| Body Mass Index (BMI)⁎ | 28.0 ± 5 | 28.5 ± 4.82 | 27.6 ± 5.17 | NS |

| Etiology (%) MASLD ALDMetALD Autoinmune Hepatitis (AIH) Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC)Overlap (AIH/PBC)Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis Chronic hepatitis C Cryptogenic Others | 40.915.26.14.56.16.14.534.57.6 | 43.815.66.303.19.43.13.13.112.5 | 38.214.75.98.88.82.95.92.95.92.9 | NS |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (%) | 22.7 | 21.9 | 23.5 | NS |

| Child‒Pugh A/B/C (%) | 13.6/57.6/28.8 | 12.5/56.2/31.2 | 14.7/58.8/26.5 | NS |

| MELD- Na score⁎ | 17.3 ± 5 | 17.2 ± 5 | 17.3 ± 5 | NS |

| Creatinine (mg/dL)⁎ | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | NS |

| Na (mEq/L)⁎ | 137±3 | 136±3 | 137±3 | NS |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dl)⁎ | 3.3 ± 3 | 3.2 ± 3.4 | 3.2 ± 2.6 | NS |

| INR⁎ | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | NS |

| Albumin (g/dL)⁎ | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | NS |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL)⁎ | 12.0 ± 2 | 11.8 ± 1.6 | 12.1 ± 2.4 | NS |

| Platelets count (x 103/uL)⁎ | 95±88 | 111±113 | 78±50 | NS |

| Hepatic encephalopathy (%) | 71.2 | 71.9 | 70.6 | NS |

| Ascites (%)Without ascitesGrade IGrade IIGrade III | 28.821.236.413.6 | 28.118.837.515.6 | 29.423.435.311.8 | NSNSNSNS |

| Use of NSBB | 77.3 | 84.4 | 70.6 | NS |

| CLDQ (points)⁎ | 4.23 | 4.36 | 4.15 | NS |

All patients in the intervention group completed the physical therapy sessions as long they were adjusted following the protocol (see supplementary material).

Reminders to maximize compliance with the protocol were conducted every 4 weeks in 100 % of the patients in both groups.

3.1Results: Liver frailty index (LFI) and frailty reversalAt the study's conclusion, the LFI was 4.05±0.52 in the control group and 3.89±0.63 in the intervention group, demonstrating a progressive improvement in ΔLFI in the intervention group. This change became statistically significant at week 12, with ΔLFI of 0.40±0.08 in the intervention group versus 0.14±0.07 in the control group (p = 0.02). Thus, the intervention group achieved the clinically significant 0.3-point improvement in LFI (Fig. 2).

By the end of the study, the distribution of frail, pre-frail, and robust patients in the intervention versus control groups was 15.6 % vs. 23.5 %, 68.8 % vs. 73.5 %, and 6.2 % vs. 2.9 %, respectively. There was a significant reduction in the proportion of frail patients in the intervention group compared to the control group (28.1 % vs. 8.8 %, p = 0.02, Fig. 3).

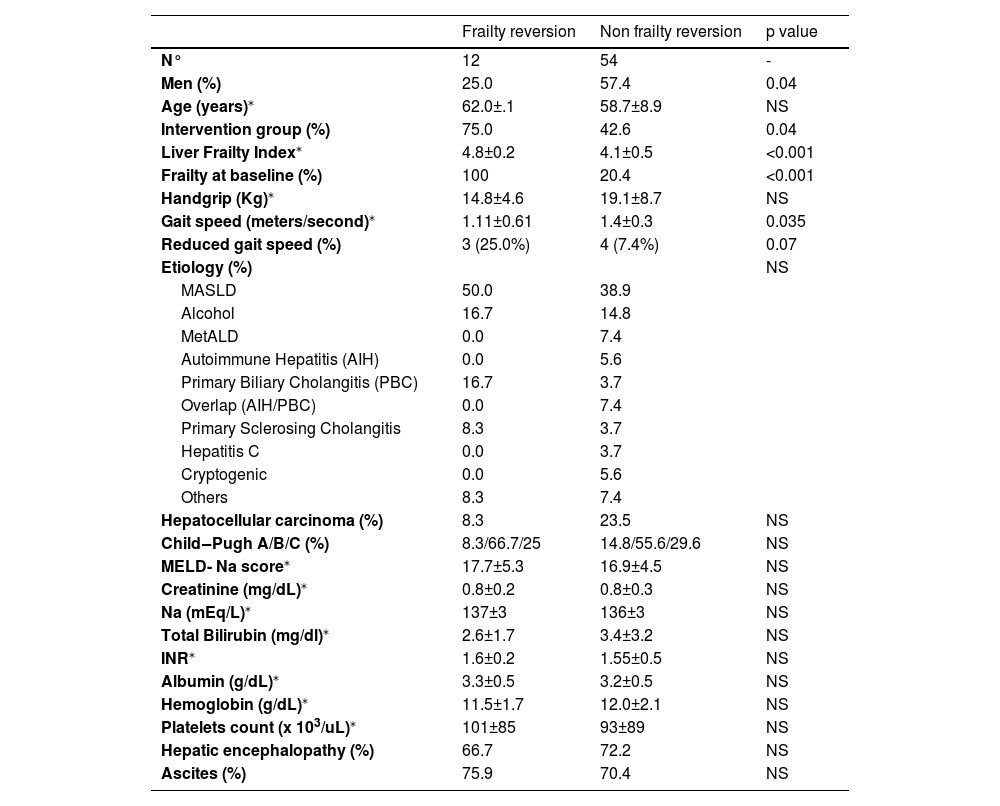

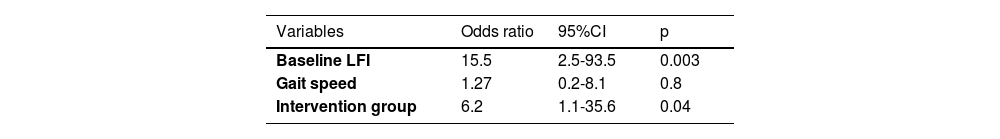

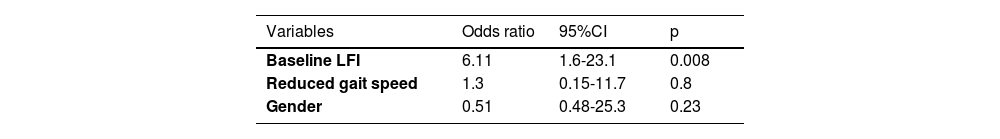

3.2Factors associated with frailty reversalBaseline LFI, male gender, and reduced gait speed were associated with frailty reversal (Table 2). Independent predictors of frailty reversal included baseline LFI (OR 15.5, p = 0.003) and assignment to the intervention group (OR 6.2, p = 0.04; Table 3).

Baseline characteristics of patients who experimented frailty reversion vs those without frailty reversion at the end of study.

| Frailty reversion | Non frailty reversion | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N° | 12 | 54 | - |

| Men (%) | 25.0 | 57.4 | 0.04 |

| Age (years)⁎ | 62.0±.1 | 58.7±8.9 | NS |

| Intervention group (%) | 75.0 | 42.6 | 0.04 |

| Liver Frailty Index⁎ | 4.8±0.2 | 4.1±0.5 | <0.001 |

| Frailty at baseline (%) | 100 | 20.4 | <0.001 |

| Handgrip (Kg)⁎ | 14.8±4.6 | 19.1±8.7 | NS |

| Gait speed (meters/second)⁎ | 1.11±0.61 | 1.4±0.3 | 0.035 |

| Reduced gait speed (%) | 3 (25.0%) | 4 (7.4%) | 0.07 |

| Etiology (%) | NS | ||

| MASLD | 50.0 | 38.9 | |

| Alcohol | 16.7 | 14.8 | |

| MetALD | 0.0 | 7.4 | |

| Autoimmune Hepatitis (AIH) | 0.0 | 5.6 | |

| Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC) | 16.7 | 3.7 | |

| Overlap (AIH/PBC) | 0.0 | 7.4 | |

| Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis | 8.3 | 3.7 | |

| Hepatitis C | 0.0 | 3.7 | |

| Cryptogenic | 0.0 | 5.6 | |

| Others | 8.3 | 7.4 | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (%) | 8.3 | 23.5 | NS |

| Child‒Pugh A/B/C (%) | 8.3/66.7/25 | 14.8/55.6/29.6 | NS |

| MELD- Na score⁎ | 17.7±5.3 | 16.9±4.5 | NS |

| Creatinine (mg/dL)⁎ | 0.8±0.2 | 0.8±0.3 | NS |

| Na (mEq/L)⁎ | 137±3 | 136±3 | NS |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dl)⁎ | 2.6±1.7 | 3.4±3.2 | NS |

| INR⁎ | 1.6±0.2 | 1.55±0.5 | NS |

| Albumin (g/dL)⁎ | 3.3±0.5 | 3.2±0.5 | NS |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL)⁎ | 11.5±1.7 | 12.0±2.1 | NS |

| Platelets count (x 103/uL)⁎ | 101±85 | 93±89 | NS |

| Hepatic encephalopathy (%) | 66.7 | 72.2 | NS |

| Ascites (%) | 75.9 | 70.4 | NS |

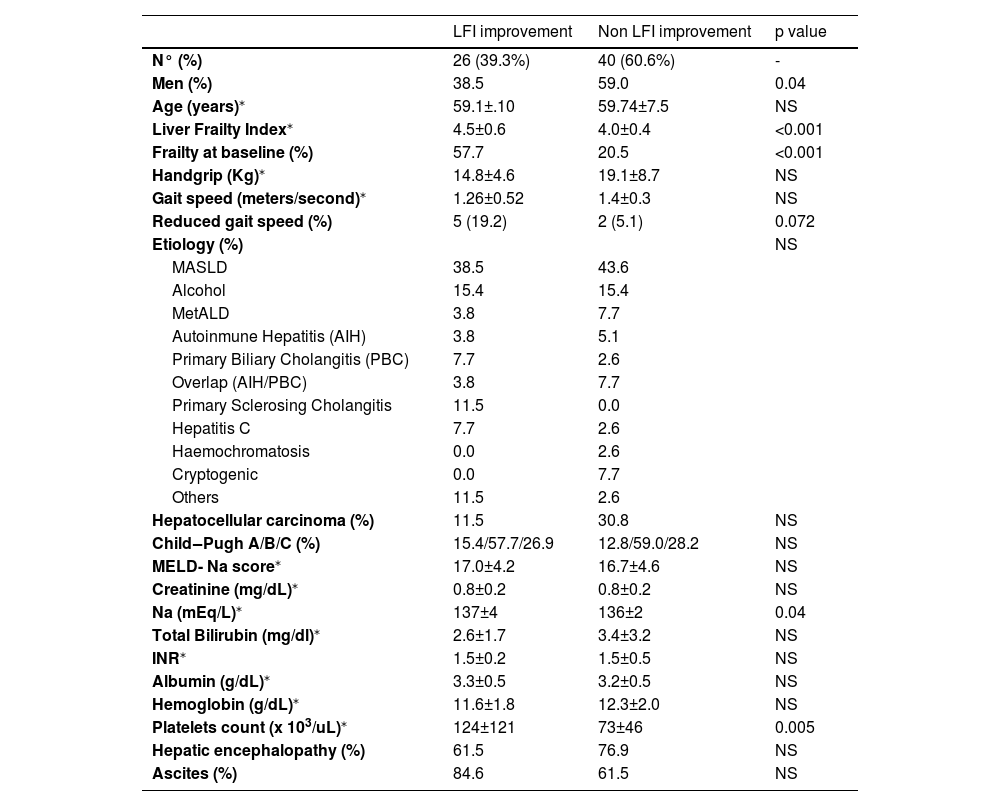

Based on the criteria outlined in the methods section, 39.3 % of patients achieved an LFI improvement of ≥0.3 points. Improvement was more frequent in the intervention group compared to the control group (48.4 % vs. 32.4 %, p=NS). Factors associated with LFI improvement included male gender, reduced gait speed, and baseline LFI (Table 4). Baseline LFI was the only independent predictor of LFI improvement (OR 6.11, p = 0.008; Table 5).

Variables associated to LFI improvement.

| LFI improvement | Non LFI improvement | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N° (%) | 26 (39.3%) | 40 (60.6%) | - |

| Men (%) | 38.5 | 59.0 | 0.04 |

| Age (years)⁎ | 59.1±.10 | 59.74±7.5 | NS |

| Liver Frailty Index⁎ | 4.5±0.6 | 4.0±0.4 | <0.001 |

| Frailty at baseline (%) | 57.7 | 20.5 | <0.001 |

| Handgrip (Kg)⁎ | 14.8±4.6 | 19.1±8.7 | NS |

| Gait speed (meters/second)⁎ | 1.26±0.52 | 1.4±0.3 | NS |

| Reduced gait speed (%) | 5 (19.2) | 2 (5.1) | 0.072 |

| Etiology (%) | NS | ||

| MASLD | 38.5 | 43.6 | |

| Alcohol | 15.4 | 15.4 | |

| MetALD | 3.8 | 7.7 | |

| Autoinmune Hepatitis (AIH) | 3.8 | 5.1 | |

| Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC) | 7.7 | 2.6 | |

| Overlap (AIH/PBC) | 3.8 | 7.7 | |

| Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis | 11.5 | 0.0 | |

| Hepatitis C | 7.7 | 2.6 | |

| Haemochromatosis | 0.0 | 2.6 | |

| Cryptogenic | 0.0 | 7.7 | |

| Others | 11.5 | 2.6 | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (%) | 11.5 | 30.8 | NS |

| Child‒Pugh A/B/C (%) | 15.4/57.7/26.9 | 12.8/59.0/28.2 | NS |

| MELD- Na score⁎ | 17.0±4.2 | 16.7±4.6 | NS |

| Creatinine (mg/dL)⁎ | 0.8±0.2 | 0.8±0.2 | NS |

| Na (mEq/L)⁎ | 137±4 | 136±2 | 0.04 |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dl)⁎ | 2.6±1.7 | 3.4±3.2 | NS |

| INR⁎ | 1.5±0.2 | 1.5±0.5 | NS |

| Albumin (g/dL)⁎ | 3.3±0.5 | 3.2±0.5 | NS |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL)⁎ | 11.6±1.8 | 12.3±2.0 | NS |

| Platelets count (x 103/uL)⁎ | 124±121 | 73±46 | 0.005 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy (%) | 61.5 | 76.9 | NS |

| Ascites (%) | 84.6 | 61.5 | NS |

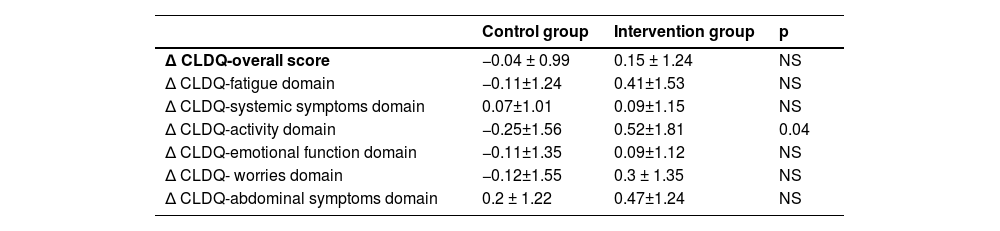

Quality of life, assessed via the CLDQ, showed significant improvement in the activity domain within the intervention group by the study's end (p = 0.04; table 6).

Change of CLDQ score at the end of study. Overall score and each domain are detailed. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

No significant differences were observed in the frequency of satisfactory compliance to physical therapy recommendations between the intervention and control groups (68.6 % vs. 79.2 %, p = 0.1). Patients in the control group completed a similar number of exercise sessions as those in the intervention group (31±8.6 vs 36±6.1, p = 0.2). However, compliance with the nutritional intervention was significantly lower in the control group compared to the intervention group (57.1 % vs. 73.4 %, p = 0.049).

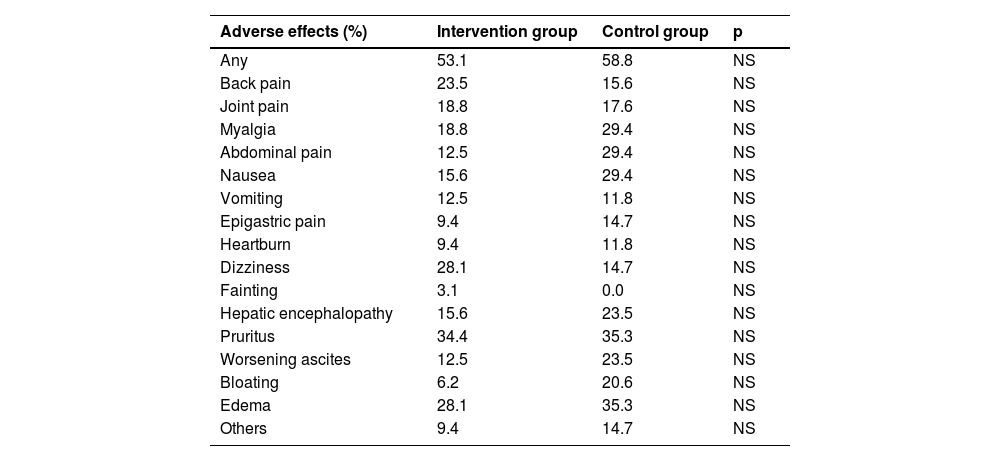

No differences in the frequency of adverse effects on each arm were found. These are detailed in table 7.

Adverse effects.

Frailty, a concept that originated in geriatrics, signifies increased vulnerability to stressors and is consistently linked to adverse outcomes. In a recent 4-year prospective cohort study of cirrhotic patients, frailty independently predicted worse prognosis, regardless of MELD-Na, hepatocellular carcinoma, or hepatic encephalopathy [16].

In cirrhotic patients, several mechanisms have been associated with their development such as increased intestinal permeability, which promotes bacterial translocation and systemic inflammation [17,18]. These factors are commonly observed in listed patients as those included in our study. However, there is no consistent evidence on how exercise and nutrition influence these factors, if at all.

Hepatic metabolic dysfunction drives a hypercatabolic state, severe anorexia, and early satiety due to ascites and cirrhosis complications. Non-hepatic contributors to frailty include age-related muscle loss (1 % annually until 70, then 1.5–2.5 %) and comorbidities like diabetes, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and kidney diseases. Alcohol intake and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease further exacerbate liver and muscle toxicity in listed patients [13].

Importantly, pre-transplant physical frailty was shown to be significantly associated with post-transplant mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 2.1; 95 % CI 1.4–3.3) [11]. After LT, frailty increases healthcare utilization and independently predicts ICU stays ≥4 days, hospital stays ≥12 days, and non-home discharge post-transplant [10]. Finally, frailty before LT has been associated with worse health related quality of life 1 year after LT (mainly related to the physical component of healthcare questionnaires). [11] Even in the setting of very short waiting time in the list frailty evaluated by LFI was associated to a higher chance of early and late post-transplant complications as well as significative longer in hospital stay [19].

Frailty can be assessed using various tools, including handgrip strength, body composition analysis, the Karnofsky Performance Scale, the Fried Frailty Phenotype (FFP), and gait speed, among others. Our group has shown that FFP is a very good predictor of long-term survival. Interestingly, gait speed ≤0.8 m per second predicts survival effectively and can be easily measured with minimal training for medical personnel [16]. The Liver Frailty Index is a widely validated test specifically designed for patients with cirrhosis. It involves specifying gender, measuring handgrip strength, conducting a balance test, and timing five chair stands, all of which require minimal time to complete. This objective tool is easily implementable in outpatient clinical settings [6].

Given frailty's clinical impact, available diagnostic tools, and the need to optimize liver graft use, prehabilitation is recommended to enhance patient condition pre-transplantation and improve outcomes. However, no specific interventions are currently recommended for patients with cirrhosis.

Some studies show that exercise improves key components of physical frailty (functional/aerobic capacity, sarcopenia) and quality of life in chronic liver disease and after liver transplantation without significant adverse effects related to this type of interventions [20,21]. Adherence to physical training appears to improve prognosis. Li et al. conducted an ambispective study of 517 patients, finding that a median LFI improvement of 0.3 correlated with better survival. Notably, compliance with physical therapy was independently linked to increased survival (HR= 0.54 [0.31–0.94]). [22]

Jamali et al. published a systematic review including eleven randomized controlled trials (358 participants). Interventions ranged from 8 to 14 weeks and included different types of exercises. Nine studies showed statistically significant improvements in at least 1 physical fitness variable. Ten studies showed statistically significant improvements in at least 1 muscular fitness variable. Six studies showed statistically significant improvements in at least 1 quality-of-life variable [14,15].

These studies focused on physical training interventions without incorporating specific nutritional guidelines, such as kcal/kg/day, protein intake, or a structured meal schedule including a late-night snack. This omission may negatively impact on the effectiveness of the interventions.

Two recent studies highlighted the role of nutrition in frail cirrhotic patients. Lel Meena et al. randomized 100 patients to standard care or intensive dietitian-supported home-based nutritional therapy, with a 6-month follow-up. LFI improvement was greater in the intervention group (0.8 vs. 0.4; P < 0.001), and hospitalization rates were lower (19 [38 %] vs. 29 [58 %]; P = 0.04). [23] Iramolpiwat et al. randomized 54 patients to BCAA supplementation or standard nutrition. At 16 weeks, the BCAA group showed greater LFI improvement (−0.36 ± 0.3 vs. −0.15 ± 0.28; P = 0.01), higher serum albumin (+0.26 ± 0.27 vs. +0.06 ± 0.3 g/dl; P = 0.01), and a higher frailty reversal rate (36 % vs. 0 %; P < 0.001). Additionally, the BCAA group had significant improvements in the physical component score of the SF-36 questionnaire [24]. Therefore, nutritional interventions appear justified for frail patients with cirrhosis.

Given the evidence, combining physical training with nutritional intervention may improve outcomes following predictable stressors like surgery, infections, bleeding, and liver transplantation. This rationale guided the design of our trial.

We demonstrated that a dual intervention significantly improved LFI in a short period, a critical finding given the unpredictable availability of liver grafts and the limited time before transplantation or death in patients with higher MELD-Na scores. Frequent patients contact (every two weeks) enhanced adherence to the trial, with most reporting satisfactory compliance to physical recommendations, showing no significant differences between the intervention (68.8 %) and control (79.4 %) groups (p = 0.1). The intervention group received more specific and regularly supervised physical recommendations (dietitian evaluated patients every four weeks in the intervention group), likely avoiding protocol deviations providing an advantage over the control group. This is particularly important given that some patients may report adherence to exercise but fail to strictly follow the prescribed recommendations. Nutritional compliance was lower in the control group, which is unsurprising as the intervention group received periodic guidance to reinforce recommendations, prevent deviations, and tailor food options to individual needs.

We observed a significant reduction in the proportion of frail patients in the intervention group compared to control group (−28.1 % vs. −8.8 %; P = 0.02), making the trial's primary outcome clinically meaningful as it reflects a phenotypic change. While several variables were associated with reduced frailty, only baseline LFI and assignment to the intervention group were independent predictors, highlighting the intervention's effectiveness and the importance of targeting sicker patients.

Given that small LFI changes (≥0.3) are linked to mortality [22], we assessed this in our cohort and found that 39.3 % of patients showed LFI improvement. Factors associated with improvement included male gender, reduced gait speed, and baseline LFI.

Baseline LFI's independent association with frailty reversal suggests that intervention is essential for the frailest patients. While future studies are needed to confirm this, our findings clearly demonstrate that the strategy employed in the intervention arm significantly facilitated frailty reversal. Importantly, consistent with other studies, the CLDQ results showed a significant improvement in the intervention group, particularly in the physical activity domain. On the other hand, the intervention appears to be safe considering the side effects in both arms.

Importantly, most patients in both groups achieved satisfactory compliance with the physical intervention. At least part of this achievement is the result of frequent calls as detailed in methods section. This is notable, as compliance is linked to better outcomes and may partially explain the trial's positive results. The breakdown of the compliance for physical and nutritional intervention on each group can be seen in supplementary material 4)

Our study has some limitations. First, while it is a positive trial, experience with specific dual interventions is limited, and multicenter studies in diverse populations are needed. Additionally, its impact on medium- and long-term prognosis remains unexplored. Second, the study population comprised highly motivated liver transplantation candidates; evaluating non-listed patients would provide broader insights. Third, the findings may not apply to all cirrhotic patients, as we excluded those with severe encephalopathy (unable to follow instructions), hepatocellular carcinoma beyond Milan criteria (due to incurable and debilitating disease), or severe extrahepatic mobility limitations (preventing LFI assessment or participation in interventions). Patients with recent hospitalization were also excluded, as their condition may not reflect baseline health due to immobility or undernutrition. Fourth, patients were frequently contacted and periodically evaluated for the dietitian and physical therapist. Most probably, this strategy is not easy to apply at every center.

Finally, bioelectrical impedance was not measured due to the high prevalence of ascites and edema in our patient cohort. However, most listed patients at our center were screened at some point.

Nevertheless, we believe that our study adds important information to the field, considering that it tested a very specific strategy that can be replicated (see supplementary material).

We think that a significant strength of this trial is that it tested a combined strategy based on the positive results of previous studies that evaluated nutritional and physical interventions separately. We thought that the combination of both strategies is rational and possibly has an additive or even synergistic effect over the patient’s status.

5ConclusionsWe conclude that a dual strategy of physical and nutritional interventions improves LFI and significantly reduces frailty in patients with cirrhosis listed for liver transplantation.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributionsAll authors fulfilled the ICMJE criteria for authorship and contributed to the following aspects: CB, DR and RC: design of the original protocol draft. AG, SV and SC: designed of the strategies employed in the study groups. CG, IT, NL and NK: performed the measurements and the follow up contact. CB: statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. No data is being shared in the present submission

None.

This study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT06149026).