Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the destruction of myelin in the brain and spinal cord due to loss of immune tolerance to myelin. This leads to the development of multifocal zones of inflammation with infiltrations of T-lymphocytes and macrophages accompanied by increased oxidative stress that contributes importantly to its pathogenesis [1]. Recurrent episodes of demyelination and axonal injury are primarily mediated by CD4-positive T-helper cells with a pro-inflammatory Th1 phenotype, macrophages, and soluble mediators of inflammation, pointing to complex deterioration of immune system effectors in the development of MS.

Bilirubin, the end product of the heme catabolic pathway in the intravascular compartment, has long been considered only a hallmark of an underlying liver or hemolytic disease with potentially toxic properties when critically elevated [2]. It is also well recognized that serum bilirubin is affected by various biological factors, including nutrition and other lifestyle factors, sex, age, concomitant medication that may interfere with bilirubin metabolism or impair liver function [3], which complicate the interpretation of bilirubin data in the population studies.

However, data from the last two decades convincingly proved that mild elevation of bilirubin exerts pleiotropic beneficial activities towards various pathologic conditions including cardiovascular [4] or cancer diseases [5].

Apart from powerful reactive oxygen species (ROS)-scavenging activities, bilirubin potently affects functions of the immune system acting as a strong immunosuppressive agent on almost all effectors of both adaptive and innate immune response [6].

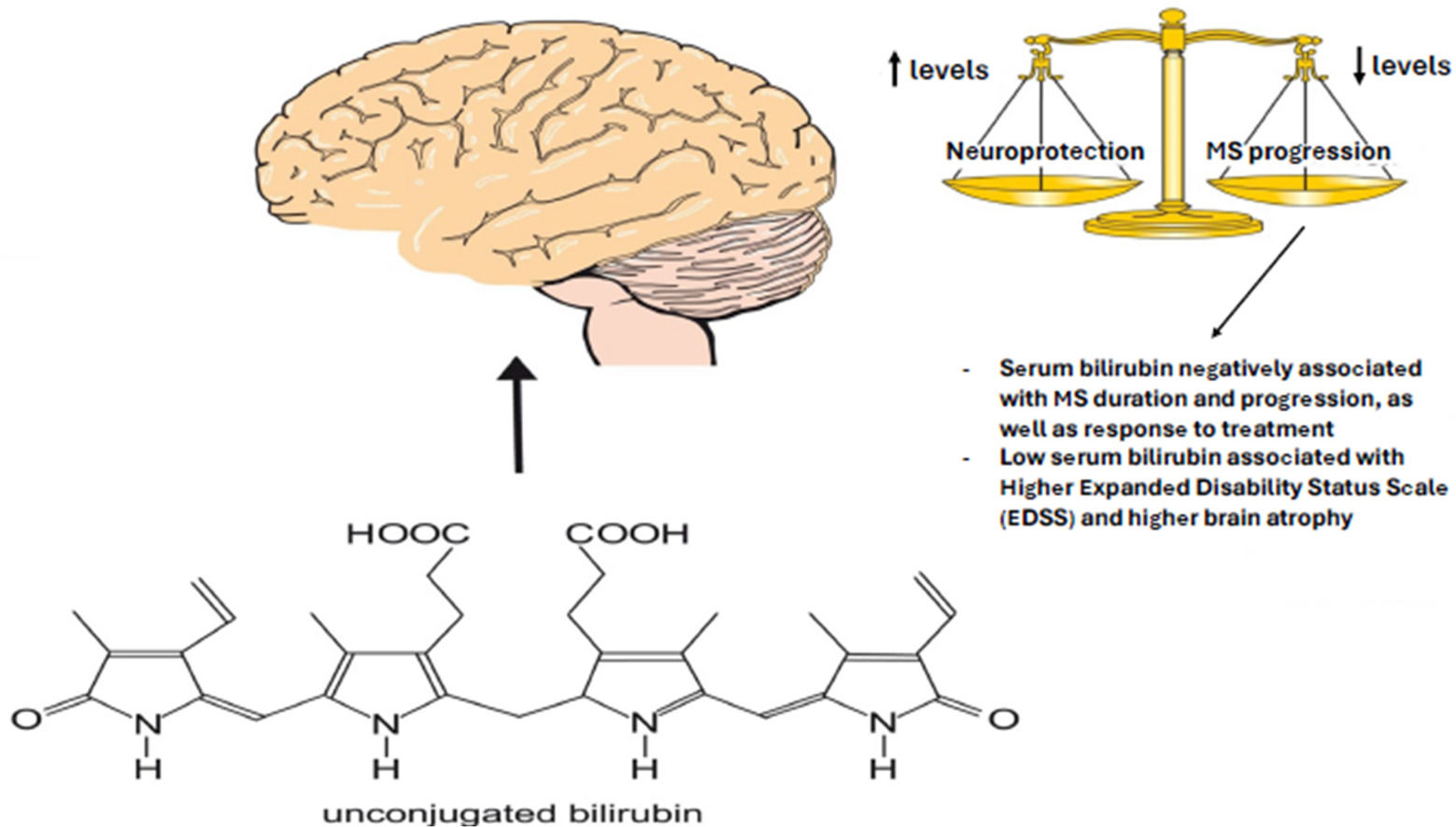

The possible roles of bilirubin in neurodegenerative diseases have been subject of recent extensive reviews demonstrating, based on reported studies, that bilirubin exerts wide protective activities against a variety of these diseases [7–10].

The first report on the possible negative association between serum bilirubin concentrations and MS was published in 2011 in a small Chinese study [11]. Serum bilirubin was also lower in both patients with a clinically isolated syndrome as well as relapsing-remitting phenotype [12]. In this study, a relationship between an increased disease burden, and disease duration with reduced serum bilirubin concentrations was clearly demonstrated [12]. Consistent with these observations, a large data-mining study in almost 5,000 Caucasian and African-American MS patients also revealed a negative association between serum bilirubin concentrations and MS [13]. The low prevalence of MS in subjects with benign hyperbilirubinemia (Gilbert´s syndrome) was reported in a conference paper in 2015 by Iranian authors [14].

A similar negative association of serum bilirubin concentrations was also reported in patients with neuromyelitis optica (NMO also known as Devic disease, a severe autoimmune astrocytopathy) [15] and patients with optic neuritis due to demyelinating disease such as MS or NMO [15].

Since previously reported clinical studies did not evaluate the relationship of serum bilirubin with comprehensive clinical and radiological correlates of MS patients, the objective of the present study was to analyze serum bilirubin concentrations and TA tandem repeat variants of the UGT1A1 promoter gene (responsible for the manifestation of Gilbert´s syndrome in the Caucasian population [2,16]) in a large cohort of MS patients with multiple determinations of serum bilirubin concentrations. Furthermore, we investigated the role of bilirubin metabolism in neurodegeneration in MS patients.

2Patients and methods2.1Study populations2.1.1PatientsIn the study a cohort of 4,679 eligible patients with 60,527 determinations of serum bilirubin were recruited. Inclusion criteria included age over 18 years, diagnosis of MS according to the 2017 McDonald criteria [17], normal activities of all liver function enzymes, and available assessment of neurological disability by Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) within 3 months before or after the determination of serum bilirubin. In total, 1,983 patients (with 32,107 determinations of serum bilirubin) did not meet the inclusion criteria, and thus the final analysis was carried out in 2,696 consecutively enrolled patients with MS from January 2005 to December 2019 in the MS Centre of the Department of Neurology of the General University Hospital in Prague with regular follow-up at this Centre. A great proportion of the patients (n=1,141 (42.3 %) had at least 10 determinations of serum bilirubin during their follow-up. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that was performed within 3 months before or after the determination of serum bilirubin and at least one month after high-dose steroids was available in most patients (n=1,699; 4,424 MRI visits).

2.1.2ControlsA total of 2,621 individuals (1,250 men and 1,371 women, aged 25-64 years) from the general population of the Czech Republic were used to compare the bilirubin concentration data obtained from the MS patient group. This general population subset was derived from the cross-sectional Czech post-MONICA study conducted between 2015 and 2018, consisting of subjects randomly selected from the Czech general population [18].

2.2Laboratory analysesDeterminations of serum biochemical parameters were performed on automatic analyzer (Cobas R8000 Modular analyzer, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). To determine the prevalence of phenotypic GS (based on the upper limits of physiological bilirubin concentration and liver enzyme activities), the following values were used: bilirubin >17 μmol/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) >0.78 μkat/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) >0.72 μkat/L, and γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) >0.84 μkat/L.

2.3MRI acquisition and analysisAll MRI scans of the examined patients were performed in the Department of Radiology of the General University Hospital in Prague using the same protocol on the same scanner (1.5 T Gyroscan; Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) that did not undergo any major hardware upgrades during the study. The MRI protocol included fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and T1-weighted 3-dimensional turbo field echo (T1-WI/TFE 3D) sequences. Brain volume was measured using ScanView software developed in-house for semi-automated measurement of lesion volume, brain volume, and brain parenchymal fraction (BPF) using a segmentation-based approach. Brain volumes were normalized with respect to total intracranial volume (ICV). Normalized brain volumes were calculated as follows: BPF=brain volume/ICV. The volume of T2 lesion was measured from the FLAIR sequence.

ScanView has been validated for both accuracy and reproducibility in multiple studies and has demonstrated high concordance with established volumetric tools such as SIENA, FreeSurfer, and Jim [19,20]. Specifically, cross-sectional measures such as whole brain and lesion volumes showed strong correlations, while longitudinal assessments of brain volume change also demonstrated robust agreement. The estimated measurement error for brain volume loss using ScanView is approximately 0.3 %, which is within acceptable limits for both clinical and research settings. Due to the semiautomated nature of the processing pipeline, inter-rater variability is expected to be minimal. A sensitivity analysis of gray matter segmentation revealed a negligible effect on gray matter volume estimates. While ScanView exhibited slightly higher intra-individual variability in longitudinal whole-brain volume measurements compared to SIENA, its overall accuracy remained comparable to that of established techniques. A detailed description of the MRI acquisition protocol, together with the ScanView technique, and its comparison with other established volumetric software were described elsewhere [19,20].

The time between the biochemical analysis of serum bilirubin and the MRI visit did not exceed 3 months. The time between 2 consecutive MRI scans was at least 10 months (arbitrary cut-off established based on clinical practice) to increase the signal to noise ratio of the brain volumetric measures.

2.4DNA analysisThe DNA analysis of the (TA)n UGT1A1 gene promoter variants was carried out on a subset of the MS patient group (n=342, M:F ratio=0.45) and compared to the data of the Czech general population from the Czech post-MONICA study (see above). The UGT1A1 gene promoter variants (dbSNP rs3064744) were analyzed by multicolored capillary electrophoresis as previously described [21–23].

2.5Statistical methodsData are expressed as mean ± SD, or median and IQ ranges when data were not normally distributed. The cohort data was compared using the Student´s t-test or the Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test, depending on the data normality. Percentage counts were compared using the chi-square test. ANOVA on Ranks with Dunn’s post hoc testing was used to compare variables among individual groups of patients.

All analyses were performed with the alpha set to 0.05. Some statistical analyses were calculated using SigmaPlot v.14.5 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA), whereas the others were performed using the R (version 4.0.3) software (http://www.R-project.org). In some analyses, non-normally distributed variables were log transformed. Variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to examine multicollinearity among independent variables in one model. To avoid multicollinearity, separate models with the duration of the age, and with the disease as independent variables were used in the analyses. The vast majority of patients contributed with multiple time points, therefore, we used linear mixed models allowing to analyze repeated measures data (lmerTest package; version v3.1-3).

The association between serum bilirubin concentrations and demographic, clinical, and imaging measures was first investigated using the non-parametric Spearman’s correlation or Mann-Whitney tests. In the second step, linear mixed models were used to investigate serum bilirubin as a predictor (analyzed as independent [log x] transformed variable) of neurological disability evaluated by EDSS (analyzed as a dependent [log x+1] transformed variable). Furthermore, predictors of serum bilirubin concentration (analyzed as dependent [log x] transformed variable) were analyzed using a similar model.

Then we investigated whether serum bilirubin concentration, its absolute or relative change (all analyzed as independent variables) predict MRI measures such as T2 lesion volume, absolute change in T2 volume, BPF, relative change in BPF, and relative change in whole brain volume (all analyzed here as dependent variables). In models with log transformed dependent measures (bilirubin and T2 lesion volume measures, and EDSS) estimates for independent variables were back transformed to the original scale and represent multiplicative effects (multiplicative Beta [Bmult]) on the geometric mean of independent variables.

Furthermore, we analyzed whether different genotypes of the promoter gene UGT1A1 (TA)n are associated with differences in clinical or radiological disease activity. For these purposes, we used linear mixed models with disease activity measures as dependent variables and genotype as a categorical independent variable ((TA)6/6, (TA)6/7 and (TA)7/7).

All the mixed models were adjusted for sex, disease duration or age, relapse rate ([log x+1] transformed variable), EDSS ([log x+1] transformed variable), years from baseline visit and disease modifying treatment (DMT) status (3 categories: no DMT; low efficacy DMT [glatiramer-acetate, dimethyl fumarate and interferons] and moderately high to high efficacy DMT [fingolimod and natalizumab]) at visit. Benjamini-Hochberg procedure with p < 0.05 was used to control the false discovery rate.

2.6Ethics approval and consent to participateThe study was approved by the General University Hospital Ethics Committee (Study approval Nos. 1701/12 S-IV and 39/11). The protocol for the Czech post-MONICA study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine and Thomayer Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic (Study approval No. G 14-08-04). All participants provided their informed consent. The whole study was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983. All participants provided their informed consent.

3Results3.1Basic characteristics of study subjectsThe study was carried out in 2,696 MS patients (708 men and 1,988 women, M:F ratio=0.36) with 28,501 measures of serum bilirubin concentrations. The median age of the patients was 37.1 years, the median duration of the disease was 6.8 years, the median duration of follow-up was 7.2 years, and the median EDSS was 2.5 (for a detailed description, see Tab. 1).

Serum bilirubin concentrations in MS patients compared to the Czech general population.

Serum bilirubin concentrations expressed as median and IQ range. Significant results are given in bold.

DMT, disease modifying treatment; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; MS, multiple sclerosis; NA, not applicable.

*Comparison between respective MS and control groups, significant differences in particular results are given in bold.

**Low efficacy DMT: glatiramer-acetate, dimethyl fumarate, and interferons. High or moderately high efficacy DMT: fingolimod and natalizumab.

Serum bilirubin concentrations in the patients with MS at the first laboratory check-up were significantly lower compared to the general population (8.3 vs. 9.6 μmol/L) in both men (10.2 vs. 11.3 μmol/L) and women (7.7 vs. 8.3 μmol/L, P<0.001 for all comparisons, Tab. 1), and these differences were even higher when serum bilirubin concentrations used for comparison with the general population were from the last laboratory check-up after more than 7 years of follow-up (7.7 vs. 9.6 μmol/L) in both men (9.4 vs. 11.3 μmol/L) and women (7.3 vs. 8.3 μmol/L, P<0.001 for all comparisons, Tab. 1).

This was due to the fact that serum bilirubin concentrations decreased significantly during the duration and progression of the disease (8.3 vs. 7.7 μmol/L at the first and last check-ups of bilirubin concentration, P<0.001). The same pattern of serum bilirubin decrease was observed for both men and women with MS (10.2 vs. 9.4 μmol/L at the first and last bilirubin concentration checks in men, P<0.001), whereas in women serum bilirubin concentrations 7.7 vs. 7.3 μmol/L at the first and last bilirubin concentration checks (P<0.001).

Hyperbilirubinemia >17 µmol/L (a phenotypic sign of Gilbert´s syndrome) in MS patients was much less frequent compared to the general population (all population: 8.2 vs. 12.5 %, P<0.001; men: 14.2 vs. 18.2 %, P<0.05; women: 6.1 vs. 7.2 %, NS, Tab. 1).

3.3The role of factors modifying serum bilirubin concentrations in patients with MS3.3.1Serum bilirubin concentrations in patients with MS according to UGT1A1 genotypeThe frequencies of individual UGT1A1 (TA)n/n genotypes did not differ between MS patients and the control population in the overall population or when analyzed separately for men and women (P > 0.05, Tab. 2). Compared to the control population, serum bilirubin concentrations tended to be lower in most UGT1A1 genotype categories of patients with MS (Tab. 2). As expected, the presence of the TA7 allele was associated with higher serum bilirubin concentrations, both in men and women, and both in the control and MS populations (Tab. 2). However, the genotypes of the UGT1A1 (TA)n promoter gene were not associated with clinical or radiological disease activity (Tab. 2). Tab. 2a

Association between serum bilirubin concentrations and UGT1A1 genotypes in MS patients and in the general population, and the disease activity of MS patients according to the UGT1A1 promoter gene genotypes.

BPF, brain parenchymal fraction; DMT, disease modifying treatment; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; MS, multiple sclerosis; NA, not applicable.

Unless otherwise indicated, data stated as median and IQ range.

Analysis of disease activity in MS patients was performed in a subset of 188 patients with 548 timepoints, in whom complete data (including MRI measures) were available.

+Includes 7 subjects with genotype (TA)5/6

++includes 1 subject with genotype (TA)6/8

+++includes 1 subject with genotype (TA)7/8.

#P < 0.01 compared to respective control group, significant results are given in bold.

*Calculated from all available measures during follow-up.

**Number and proportion of blood measurements.

***Number and proportion of blood measurements on treatment with: No immunomodulatory treatment, Low efficacy DMT: glatiramer-acetate, dimethyl fumarate and interferons; and High or moderately high efficacy DMT: fingolimod and natalizumab at baseline or at the last visit.

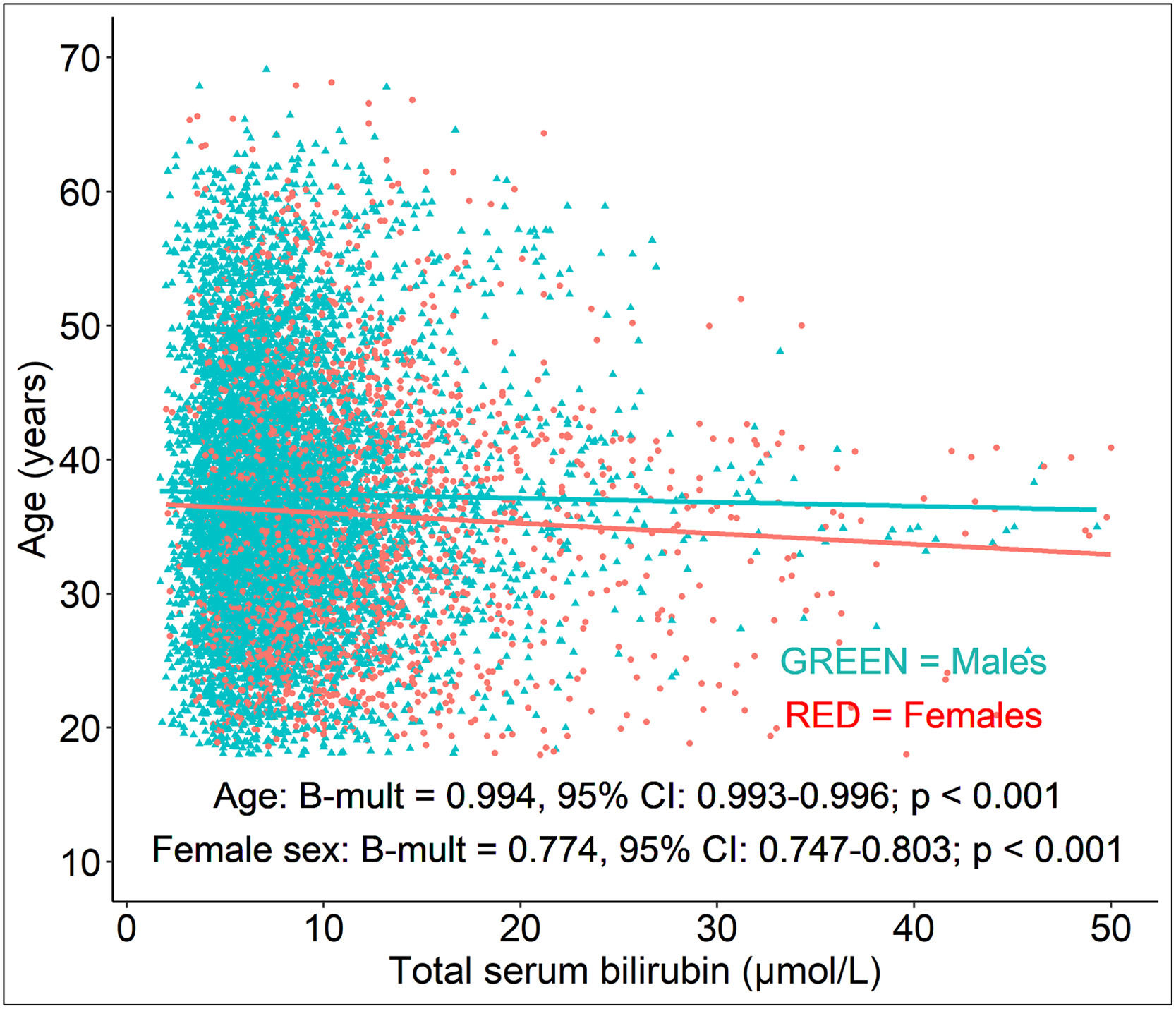

As shown above, a significant decrease in serum bilirubin concentration with longer disease duration and higher age was observed in our MS patients. An increase in the duration of the disease by 1 year was associated with a 0.8 % decrease (Bmult=0.992; 95 % CI: 0.991-0.994; P<0.001, Tab. 3) in serum bilirubin concentration. Similarly, an increase in age by 1 year was associated with a 0.6 % decrease (Bmult=0.994; 95 % CI: 0.993-0.996; P<0.001) in serum bilirubin concentration (Tab. 3, Fig. 1). All the models investigating the effect of disease duration and age on serum bilirubin concentrations were adjusted for sex, disability, relapsing activity and DMT status (Tab. 3).

Multivariable analysis of the association of serum bilirubin concentrations of MS patients as dependent variable with clinical and demographical measures.

Bmult, multiplicative beta; CI, confidence interval; DMT, disease modifying treatment; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; MS, multiple sclerosis.

Analysis performed on 2,481 patients with 23,680 timepoints, in whom serum bilirubin concentrations could be paired with EDSS. Neurological disability was assessed by EDSS.

Estimates were back transformed to the original scale and therefore represent multiplicative effects on the geometric mean of independent variables.

†Low efficacy DMT: glatiramer-acetate, dimethyl fumarate and interferons; High or moderately high efficacy DMT: fingolimod and natalizumab

††log [x+1] transformed variable.

*p<0.05, after Benjamini-Hochberg correction.

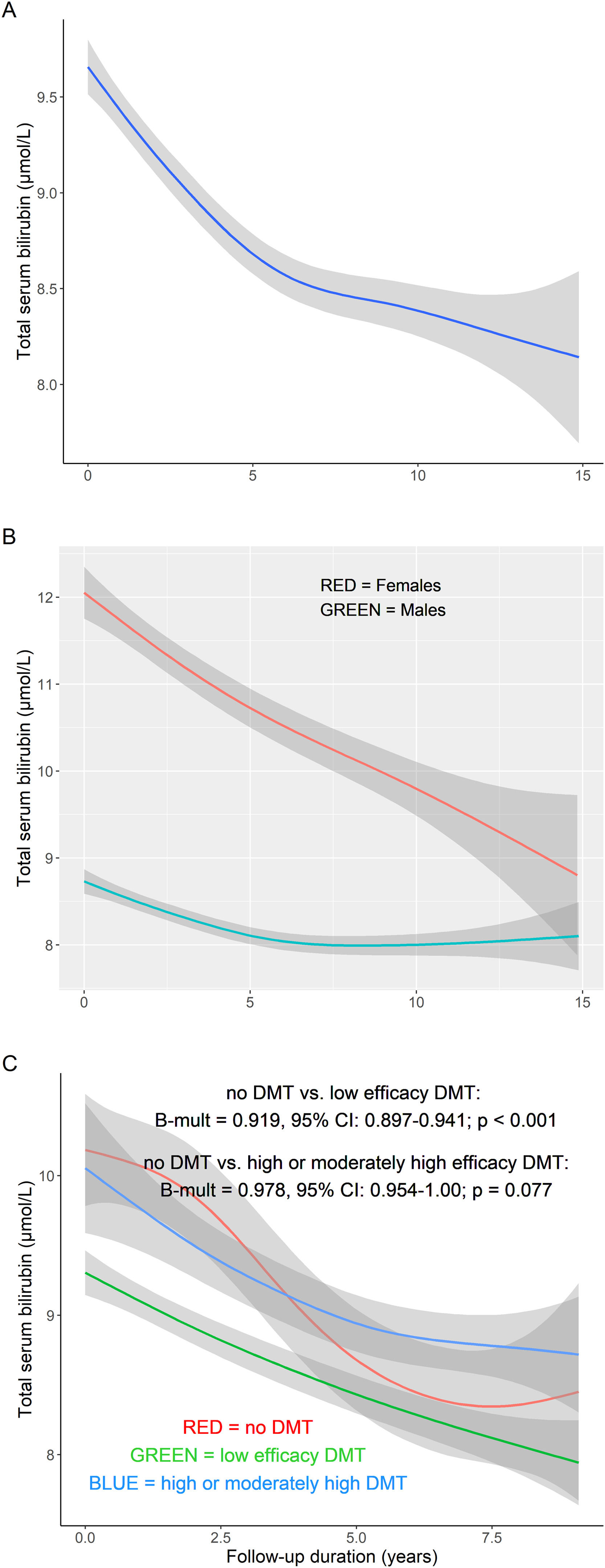

Compared to males, female MS patients had lower serum bilirubin concentrations by 23 % (Bmult=0.770; 95 % CI: 0.743-0.799; P<0.001) (Tab. 3). A greater decrease in serum bilirubin concentrations was observed in male MS patients during follow-up (interaction sex vs. follow-up duration; B = -0.005; 95 % CI: -0.009, -0.002; P<0.001) (Fig. 2a-b). As expected, smoking in MS patients was associated with lower serum bilirubin concentrations compared with never-smokers (*Bmult=0.87; 95 % CI: 0.82-0.93, P<0.001).

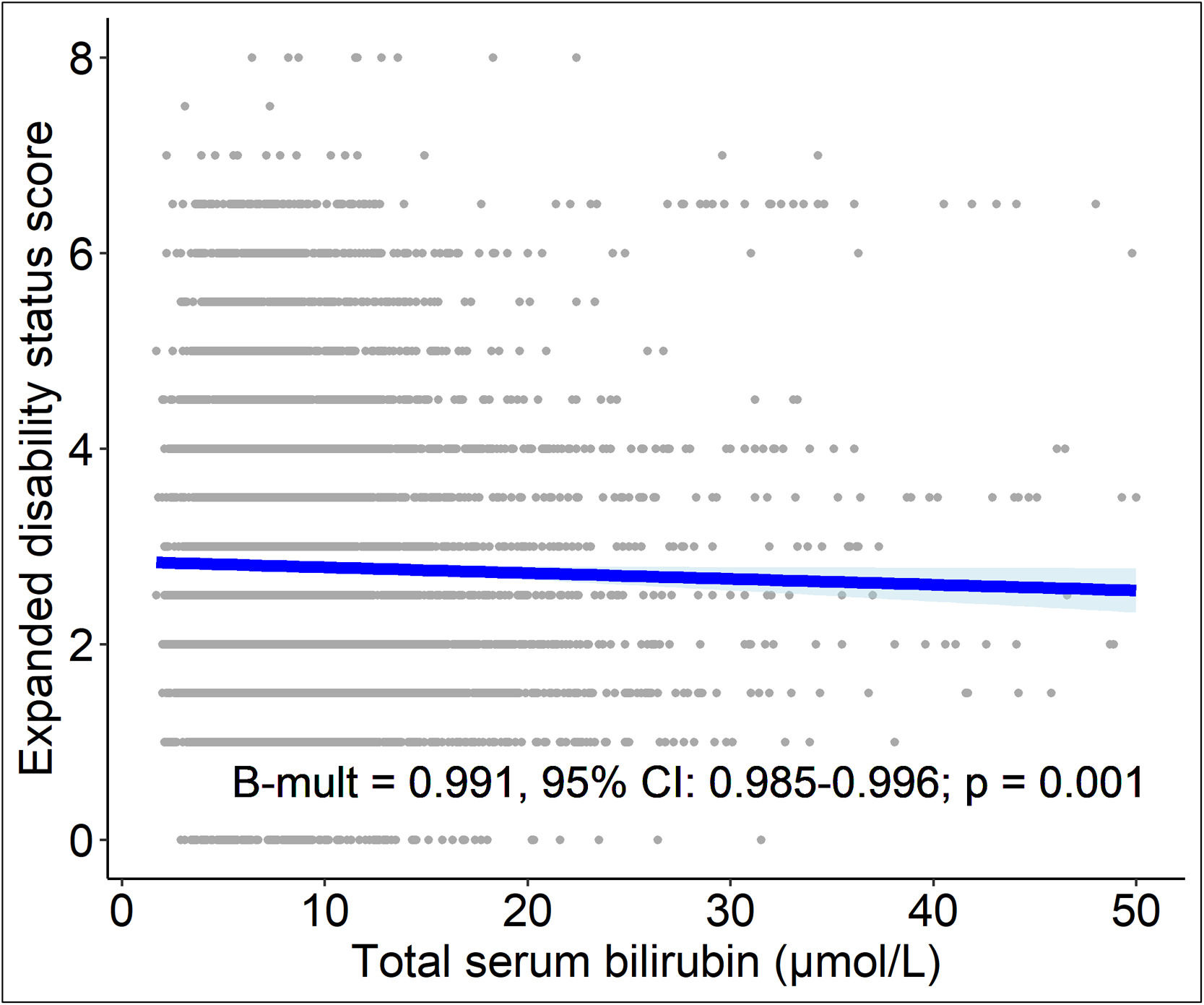

3.3.4Relationship between serum bilirubin concentrations, neurological disability and treatment response of MS patientsHigher serum bilirubin concentrations were associated with lower EDSS. Ten percent higher serum bilirubin concentration was associated with 9 % decrease of EDSS (Bmult=0.991; 95 % CI: 0.985-0.996; P=0.001, Suppl. Tab. 1 and Fig. 3).

Patients without DMT had higher serum bilirubin concentrations compared to patients treated with low efficacy DMT (Bmult=0.919; 95 % CI: 0.897-0.941; P<0.001) but not with high or moderately high efficacy DMT (P=0.077) (Tab. 3 and Suppl. Tab. 1). Patients without DMT had a greater decrease in serum bilirubin concentrations during the study compared to patients treated with high or moderately high efficacy DMT (interaction DMT status vs. follow-up duration; B=0.006; 95 % CI: 0.003-0.010; P<0.001) (Fig. 2c).

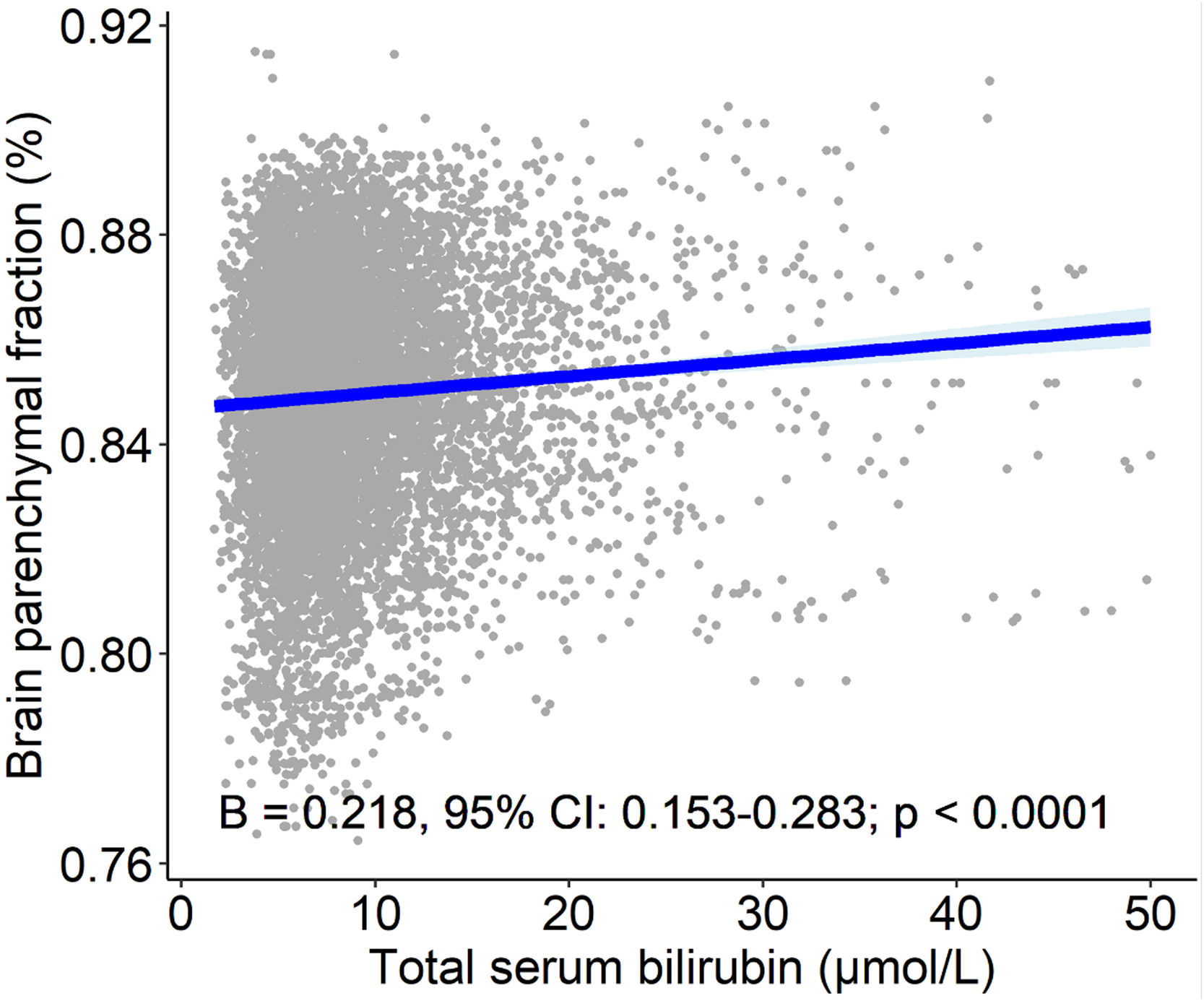

3.3.5Relationship between serum bilirubin concentrations and brain MRI measures of patients with MSHigher serum bilirubin concentration was associated with higher normalized brain volume as assessed by BPF. Ten percent higher serum bilirubin was associated with a 2.1 % (B=0.218; 95 % CI: 0.153-0.283; P<0.001, Tab. 4, Fig. 4) increase in BPF, and 100 % higher serum bilirubin was associated with an increase in BPF of more than 15 %. Relative and absolute changes in serum bilirubin concentrations were also positively correlated with percentage volume changes of BPF. Except for a weak negative association between the absolute change in serum bilirubin concentrations and the absolute increase in the T2 lesion volume, no significant associations were found between the burden of the lesion and bilirubin concentrations (Tab. 4).

Association between serum bilirubin concentrations and MRI findings in MS patients.

B, beta coefficient (estimates); Bmult, multiplicative beta; CI, confidence interval; BPF, brain parenchymal fraction.

Analysis performed on 1,699 patients with 4,424 timepoints.

Estimates were back transformed to the original scale and therefore represent multiplicative effects on the geometric mean of independent variables.

†log [x+1] transformed variable.

††log [x+20] transformed variable.

*p<0.05 after Benjamini-Hochberg correction.

Recent clinical research has convincingly proved the protective effects of serum bilirubin concentrations on the risk and development of various diseases of civilization, including neurological and neuropsychiatric diseases [2,7–10,21,24,25]. In fact, negative associations between bilirubin and MS have been reported in recent clinical studies[11–14]. Similar associations have also been reported for NMO [15] and optic neuritis [15]. The incidence rates of MS, optic neuritis, and NMO are higher among women [26], who have significantly lower serum bilirubin concentrations, as observed in both MS patients in our (Tab. 1) and other studies [11–13] as well as in general population [18,24]. Furthermore, bilirubin concentrations also correlate with the prevalence of migraine that is known to be twice as frequent in MS patients [27]. In fact, a negative association between serum bilirubin and migraine was reported in two recent Chinese studies [28,29], most likely due to bilirubin inhibitory effects against neurogenic inflammation accompanying migraine development.

Our study confirmed previous findings of significantly lower serum bilirubin concentrations in MS patients, as well as a lower prevalence of Gilbert´s syndrome, compared to the control group, which was randomly selected from the same population. Interestingly, the frequencies of the UGT1A1 promotor gene variants were comparable in the MS and control populations, indicating that, rather than genetic predisposition, bilirubin consumption during increased oxidative stress accompanying MS is responsible for the observed low serum bilirubin concentrations in MS patients.

In addition, our study revealed that serum bilirubin is negatively associated with disease duration and progression, EDSS, as well as response to treatment. In fact, there was a less progressive decrease in serum bilirubin during follow-up in patients receiving high or moderately high efficacy treatment compared to patients without therapy or treated with low efficacy DMT suggesting curing effect of the former type of treatment. Lower serum bilirubin was also associated with female sex, higher age, and smoking, as in previous reports (for a review see [3]). According to a large NHANES study, each ten-year increase in age is associated with a 0.3 μM decrease in serum bilirubin concentrations only in men [30]. However, a much more significant decrease in serum bilirubin was observed with increasing age in MS patients, both men and women. Although our patients were significantly younger compared to controls (Tab. 1), it needs to be stressed that no serum bilirubin/age dependency was observed in our Czech post-MONICA control cohort, either in overall, male or female populations (data not shown).

Importantly, lower serum bilirubin concentrations were associated with greater disability and brain atrophy of patients with MS.

There are many reasons for the observed association of altered bilirubin metabolism in MS patients. However, it must be noted that the following arguments are based on indirect, often experimental evidence, and that true mechanistic studies on the role of bilirubin in MS have not been performed so far and are highly sought-after.

It is generally recognized that due to the increased metabolic and oxygen demands of the brain, oxidative stress is one of the key players in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Among the free radical producers, NADPH-oxidase (NOX) is a major contributor to oxidative stress in these disorders, including MS [31]. Bilirubin has been reported in many studies to improve the redox status of the human body [32], to protect against radical-induced alterations in the permeability of the blood-brain barrier, thus preventing the invasion of inflammatory cells into the CNS. In fact, bilirubin inhibited the development of acute and chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model of MS [33].

One of the critical signaling pathways implicated in the pathogenesis of MS is the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)-mediated pathway which is aberrant in a variety of autoimmune diseases including MS, but also Alzheimer´s disease. Interestingly, both bilirubin and biliverdin are AhR activators [34] known to modulate IL17-producing T-helper cells (Th17), regulatory T cells (Tregs), as well as B cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells [35]. In an experimental model of EAE, AhR signaling in Treg cells was shown to increase their activity and ameliorate disease progression [36]. It is also interesting to note that Th17 cells have upregulated apolipoprotein D (apoD), a marker of pro-inflammatory status in many autoimmune and neurodegenerative diseases including MS [37]. Bilirubin is believed to be a potent binder for apoD [38], and although not investigated so far, it is tempting to speculate whether the less efficient interaction of bilirubin with apoD in MS patients who have lower systemic bilirubin concentrations may contribute to the progression of MS.

Macrophages are the other important players in the pathogenesis of MS [39]. Important regulators of the metabolic and inflammatory phenotype of macrophages are peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) [40]. In fact, the expression of PPARγ protein is decreased in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of MS patients, and the inflammation-induced reduction in PPARγ expression promotes myelin-induced foam cell formation in macrophages in MS patients [41] and, at the same time, decreases insulin sensitivity and increases neuroinflammation [42]. On the other hand, bilirubin increases PPARγ expression in an experimental mouse model of diet-induced obesity [43]. Furthermore, bilirubin was reported to influence the expression of Fc receptors in macrophages in EAE [44].

Another important mechanism by which bilirubin can exert its possible protective action may lie in its metabolic action. As an example, the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway dysregulation has been reported in various neurodegenerative diseases including MS [45]. It is also known that metformin, an antidiabetic drug, attenuates inflammatory responses by activating AMPK via suppression of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) as documented in a cuprizone-induced demyelination mouse model of MS [46]. Similarly, liraglutide, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonist restored phosphorylation of AMPK in EAE mice resulting in an anti-inflammatory and anti-demyelination effect [47]. In fact, the same effect on AMPK phosphorylation was observed in subjects with Gilbert´s syndrome [48]. Activation of AMPK pathway, via suppression of mTOR signaling, has been reported to impair Th17 cell differentiation playing an important role in MS pathogenesis (see also above) [49].

Our study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective, observational, and non-interventional longitudinal study evaluating associations that does not allow to find causality between serum bilirubin levels and analyzed variables. Second, the cohorts analyzed were of Czech origin, so the results may limit applicability to other ethnic groups with different bilirubin metabolism, variability of UGT1A1 genotypes, gene-environment interactions, or MS prevalence. Finally, due to the study design, factors that could modulate bilirubin metabolism, such as diet or other comorbidities, were not analyzed.

5ConclusionsMS patients have markedly lower serum bilirubin concentrations, most likely due to its consumption during the increased oxidative stress that accompanies this disease since the frequencies of UGT1A1 promotor gene variants were comparable in the MS and control populations. Lower serum bilirubin concentrations were more pronounced in women, with a higher age and duration of the disease, and smoking. The UGT1A1 genotypes appear to play only a marginal role. Lower serum bilirubin concentrations were associated with increased disability and brain atrophy in MS patients. The decrease in serum bilirubin with time was less in patients receiving high or moderately high efficacy treatment compared to patients without or treated with low-efficacy DMT. Collectively, these data indicate the possible protective roles of bilirubin in the pathogenesis and progression of MS. The lack of association between lower serum concentrations and relapsing activity or lesion burden suggests a dominant effect of bilirubin on neurodegeneration rather than inflammatory activity in MS. Taking into account the current relatively unsuccessful search for treatments targeting the neurodegenerative part of MS, but also other neurodegenerative diseases, it appears that modulation of serum bilirubin may affect the progression of these diseases. However, it should be noted that our observational study does not provide any mechanistic proofs or exclude a possible reverse causality. Therefore, mechanistic studies are needed to confirm our data and look for possible causal consequences.

Availability of dataThe datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors contributionsConcept and design: LV, TU, PK; care of MS patients: TU, PK, DH, EH; control cohort studies: JW, RC, DH, ML; imaging studies: LŠ, MV, JK; laboratory analyses: JW, ML; writing of article: LV, TU, PK; all authors read and agreed with the final Ms.

FundingThis work was supported by grant projects NU22-04-00193 and MH CZ-DRO-VFN64165 from the Czech Ministry of Health, project Cooperatio LF1, research area Neuroscience from the Czech Ministry of Education, projects National Institute for Research of Metabolic and Cardiovascular Diseases (Programme EXCELES, ID Project No. LX22NPO5104), National Institute for Neurological Research (Programme EXCELES, ID project no. LX22NPO5107) funded by the European Union–Next Generation EU. The funders had no role in the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Uncited references[50]

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.