Chronic viral hepatitis remains a major global public health challenge. The WHO launched the Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis in 2016, emphasizing health equity. Digital learning offers a promising solution to barriers in achieving hepatitis elimination. This study describes a digital learning initiative to strengthen primary care capacity for viral hepatitis management in the Philippines.

Materials and MethodsThe initiative utilized asynchronous computer-based training (CBT) on the HepLearn platform and synchronous telementoring via HepTalks. The CBT was developed collaboratively with the Department of Health, WHO, Hepatology Society of the Philippines, and University of the Philippines Manila. The course addressed essential hepatitis B and C topics. Telementoring paired primary care physicians with specialists from the Hepatology Society of the Philippines using Zoom for interactive case discussions. Eight one-hour sessions were conducted, each starting with expert-led didactic lectures followed by case discussions.

ResultsEvaluation included quantitative and qualitative methods: surveys, pre- and post-test assessments, and feedback forms. Among 189 enrollees, 111 (58.7 %) completed HepLearn. Mean pre-test score was 2.63 ± 0.29, rising to 7.09 ± 1.90 post-test (p<0.001), demonstrating significant knowledge gain. Participant feedback indicated high satisfaction (72 % to 98 %) with course content. Thirteen physicians participated in HepTalks. Confidence in viral hepatitis care increased significantly, with 67 % expressing strong agreement that the sessions helped them provide better care.

ConclusionsThis integrated eLearning approach demonstrates potential for scalable digital education to enhance hepatitis care in primary and remote communities. eLearning should be a strategy for eliminating viral hepatitis by 2030.

Chronic viral hepatitis remains a significant global public health concern, with an estimated 296 million cases of chronic hepatitis B and 71.1 million cases of chronic hepatitis C worldwide [1,2]. The disease sequelae of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma account for more than 1 million global deaths each year. Furthermore, viral hepatitis mortality is expected to surpass those from HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria by 2040. In the Philippines, the Department of Health reports that approximately 10 million individuals are living with chronic hepatitis B, while an estimated 439,000 have chronic hepatitis C [3,4].

In response to this pressing public health problem, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis in 2016 [5]. The strategy called for a 90% reduction in new infections and a 65% reduction in deaths by 2030, ultimately eliminating viral hepatitis as a global public health threat. It emphasized the importance of global health equity and advocated for the use of innovative approaches and technology to achieve effective elimination [5]. Primary care practitioners are recognized as crucial stakeholders in this strategy, as they are responsible for delivering care, particularly to the hard-to-reach and marginalized populations [6].

To achieve the goal of hepatitis elimination, it is essential to develop effective, scalable, and culturally sensitive strategies that address healthcare inequities. Digital learning, in particular, eLearning initiatives offers promising solutions to these challenges by equipping primary care providers with the necessary knowledge and skills for disease management unhindered by distance or time [7]. These initiatives facilitate the remote transfer of expertise from specialists to primary care providers through the use of digital technologies such as web online learning platforms and online video conferences [7]. As a result, access to specialist knowledge is improved in remote regions, while culturally sensitive care is ensured through the involvement of primary care providers [8].

A 2024 systematic review analyzing 44 studies confirmed that asynchronous, synchronous, blended, and self-directed eLearning methodologies effectively support continuous professional development among healthcare professionals [9]. Digital learning initiatives have proven effective for training primary care providers in viral hepatitis management. Project ECHO exemplifies this approach through its telemedicine-based hub-and-spoke model, where academic centers disseminate knowledge on Hepatitis C management to primary care practitioners in New Mexico [10,11]. Primary care providers trained via Project ECHO achieved equivalent sustained virological response rates compared to specialist-managed patients at academic medical centers [12]. Additionally, Project ECHO-trained providers demonstrated superior reach to marginalized populations, including intravenous drug users and indigenous communities, relative to tertiary care facilities [13]. This digital learning framework also mitigated urban-rural disparities in direct-acting antiviral utilization [14].

These findings from Project ECHO and other similar studies underscore the critical role of eLearning modalities in global hepatitis elimination strategies and healthcare equity initiatives [7,10,11,15,16]. A recent multicountry survey of 11 hepatitis B and C telementoring programs validated the Project ECHO model’s efficacy across diverse healthcare settings, emphasizing collaborative learning as a fundamental strength [16]. These data demonstrate the capacity of telementoring to enhance viral hepatitis management across high-income and low- and middle-income countries, advancing global elimination objectives [17].

In this paper, we present the pilot implementation of two eLearning initiatives, the HepLearn computer-based training (CBT) platform and the HepTalks telementoring program, designed to strengthen the capacity of public primary care providers in managing viral hepatitis in the Philippines. These interventions aim to improve provider knowledge, build clinical confidence, and enhance access to specialist guidance through digital technologies. Their relevance is especially pronounced in the Philippine setting, an archipelago where geographic barriers often limit timely access to hepatitis care. By leveraging flexible and scalable digital tools, this pilot demonstrates how eLearning initiatives can bridge the gap between specialist and primary care, contributing to more equitable and effective hepatitis service delivery at the primary care level.

2Materials and Methods2.1Site of implementationThe eLearning initiative was implemented in the Department of Health primary care public health facilities in Central Luzon Region (Region III) and Calabarzon Region (Region IVA) in the Philippines.

2.2Design of interventionThis study employed a mixed-methods educational intervention design combining asynchronous computer-based training with synchronous telementoring to enhance viral hepatitis management knowledge among healthcare practitioners.

2.3Computer-based training/HepLearn PlatformA computer-based training (CBT) platform for viral hepatitis was developed in collaboration with the Department of Health (DOH), the World Health Organization (WHO), the Hepatology Society of the Philippines (HSP), and the University of the Philippines Manila. These organizations provided the structure and content of the CBT following the interim national guidelines on viral hepatitis management [18–20].

The CBT was conducted through the Moodle learning platform provided by the University Information Management Systems Office of the University of the Philippines Manila. This was branded as the HepLearn platform. This learning platform enables access to the course material by the enrolled healthcare practitioners remotely and at their own pace. The participants must go through each topic sequentially and answer pre- and post-test to progress through the course. They can save their progress and come back at a later time to continue/complete the course.

The course was divided into 4 topics, namely: Course Introduction, Chronic Hepatitis B, Chronic Hepatitis C, and Health Promotion and Communication (Supplementary Table 1). The course content was delivered by faculty with affiliations with the Department of Health, World Health Organization, Hepatology Society of the Philippines, and STD-AIDS Cooperative Central Laboratory.

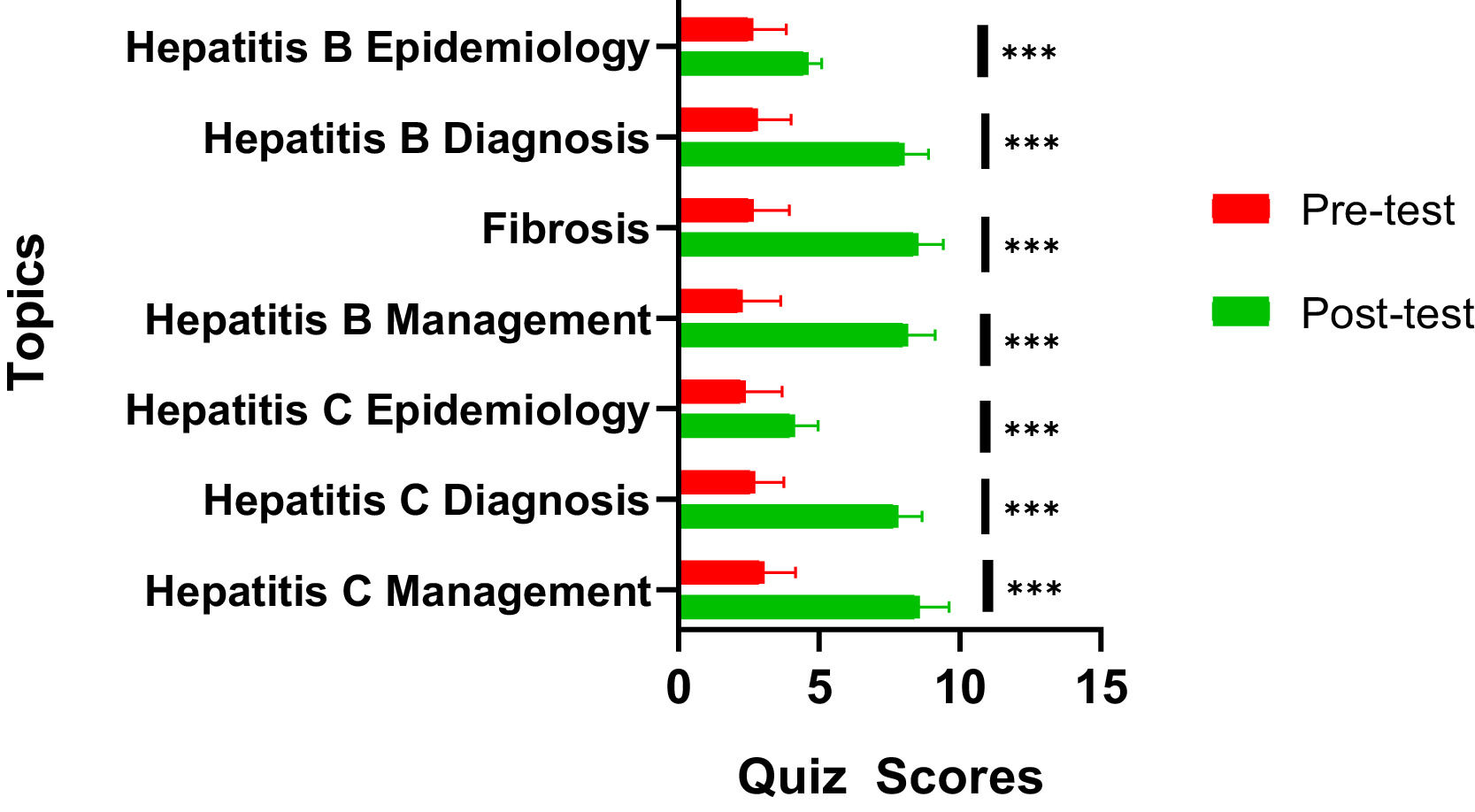

Pre- and post-test on key topics on the epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of Hepatitis B and C as well as fibrosis assessment were conducted to measure the baseline knowledge of the participants and the change in their knowledge upon completion of each topic.

2.4Telementoring/HepTalksThe telementoring program served as the synchronous aspect of the learning platform for the healthcare practitioners. The concept of the telementoring sessions was based on the hub-and-spoke model where the specialists (hepatologists in this case) represented the hub and the primary care physicians represented the spokes [21]. Telementoring sessions create virtual communities of learners by bringing together healthcare providers and subject matter experts using videoconference technology, brief lecture presentations, and case-based learning, fostering an “all learn, all teach” approach. The approach allowed the application of what had been learned in the CBT platform to real-life cases and situations.

The one-hour telementoring sessions were conducted via the Zoom video conferencing platform. It was available only to those who had completed the CBT. Schedules for the telementoring sessions were released in advance, as healthcare practitioners had varying degrees of availability to attend. A regular schedule was implemented to establish routine attendance from the healthcare practitioners. Hepatitis specialists were invited to act as moderators of the telementoring sessions to strengthen hepatitis-related concepts during the session. Each session began with a 15-minute didactic presentation by the specialists. This was followed by case presentations where the specialist and primary care providers discussed a case(s) and formulated a management plan for the case(s) based on the CBT and adapted to standard practice and local experience. The program included eight telementoring sessions, with each session covering a different topic related to viral hepatitis management. The sessions were conducted every other week for a total of 4 months (Supplementary Table 2). A graduation ceremony was held at the end of the eight sessions, and certificates were awarded to those who completed the program. Continuing education credits were provided to the participants, however these units were granted retroactively.

2.5Evaluation toolsA survey was conducted to evaluate the participants’ perceptions of both the CBT/HepLearn and telementoring/HepTalks. (Supplementary Table 3) The survey instruments were specifically developed for this study, adapted from existing eLearning evaluation frameworks to suit the context of viral hepatitis training in the Philippine primary care setting. The participants were asked to evaluate the course content and course faculty and to rate the overall usefulness of the program. Both closed- and open-ended questions were utilized in the survey. Qualitative feedback from open-ended questions was analyzed using basic content analysis to identify common themes and patterns in participant responses.

2.6Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed using complete case analysis, including only participants who completed the full course and all assessments. Missing data from non-completers were not imputed. The collected data were processed, graphed, and statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). Means and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables while frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. To compare pre- and post-test scores, the Wilcoxon test was utilized with p-value < 0.05 being considered significant. Spearman's R was used for correlation analysis, with p-value of < 0.05, being considered significant.

2.7Ethics approvalThis research was approved by the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (Code: UPMREB 2020-152-01).

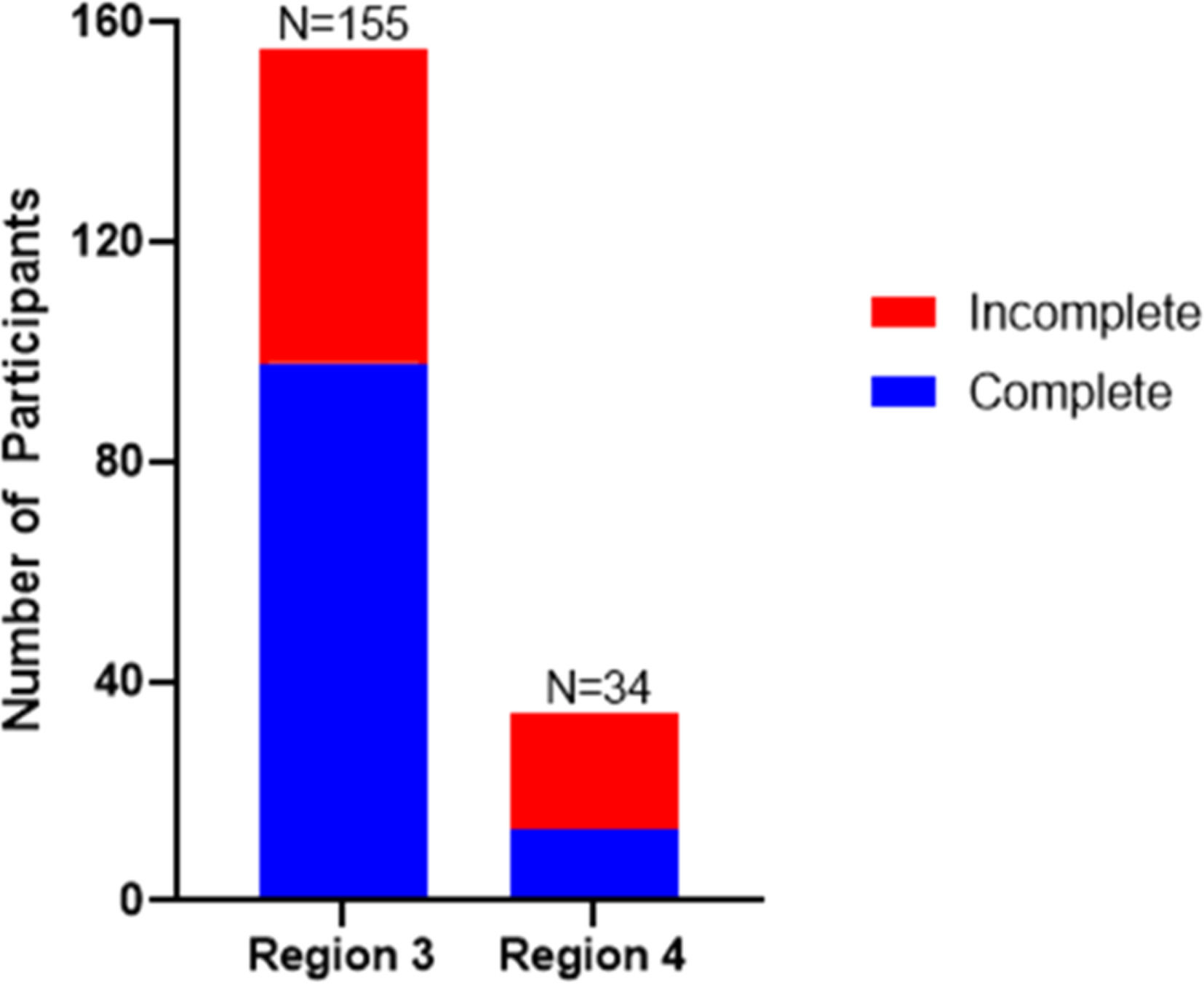

3Results3.1Computer-based Training/HepLearnA total of 189 participants from Regions III and IVA in the Philippines took part in the CBT/HepLearn platform. Of these, 98 participants from Region III successfully completed the module, while 57 were unable to finish. Meanwhile, in Region IV A, 13 participants completed the module, while 21 were unable to finish it (Fig. 1).

Non-completion of the CBT was due to a combination of contextual and structural challenges. Firstly, the training was an additional task on top of their already demanding workload at the public health centers. Although there was an official directive from the regional administrative headquarters requiring participation in the training, there was insufficient enforcement from the facility administration to ensure completion of the training program. This lack of strong enforcement may have influenced how participants prioritized the training among their other responsibilities. Additionally, limited access to reliable internet connectivity and suitable digital devices further hindered consistent participation and completion.

Fig. 2a shows that 74% of participants rated the course content as outstanding, 23% as above average, and only 3% as average. In addition, the majority of participants (73%) gave an outstanding rating to the course faculty, while 25% considered them above average, and only 2% rated them as average.

Individual ratings for each faculty member indicated high levels of satisfaction from the participants (Fig. 2b). The majority of participants (64% to 80%) gave an outstanding rating for individual faculty, while 18% to 30% gave an above-average rating. Only 1–4% gave an average rating for each faculty member.

The participants experienced several technical difficulties while accessing the HepLearn module (Fig. 3). The most significant issue was poor internet connection (31%). Moreover, 3.7% of participants experienced audio problems, 6.3% had problems navigating the site interface, while 15% were confused with the registration process.

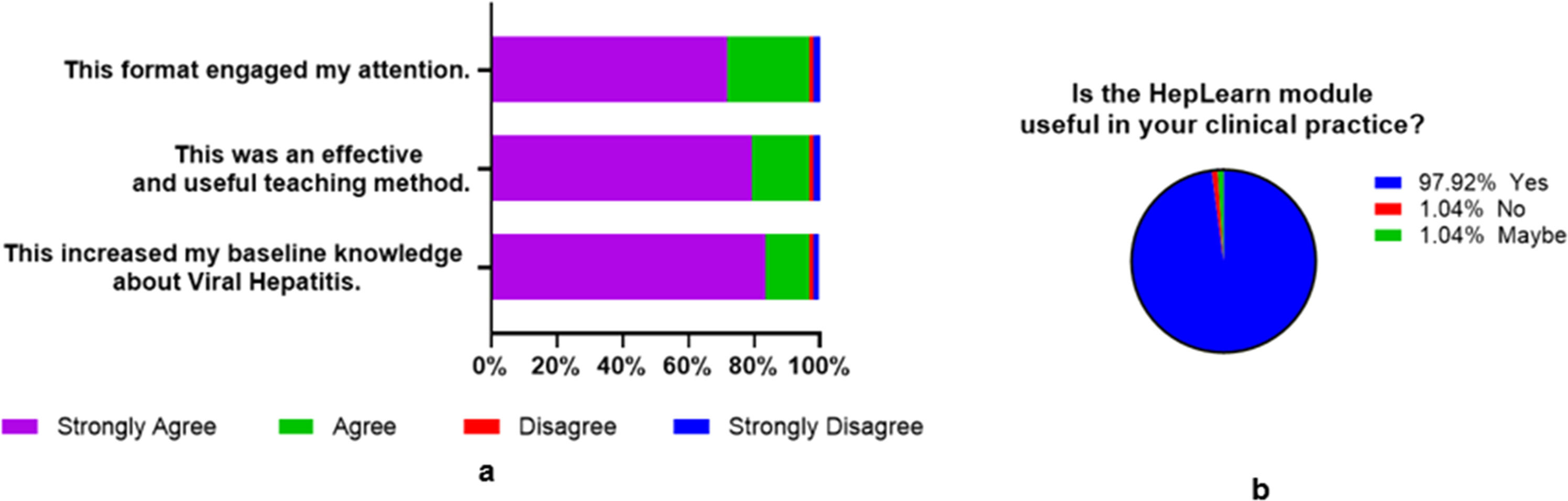

The evaluation of the participants showed that they considered the HepLearn module as an effective learning tool (Fig. 4). A large majority of the participants 72% strongly agreed, while 25% agreed that the learning format successfully engaged their attention. Additionally, 79% strongly agreed and 18% agreed that the module was an effective and useful teaching method. A significant majority, 83.3%, strongly agreed and 13.5% agreed, that the module increased their baseline knowledge of hepatitis. Furthermore, 98% of the participants found the module to be useful in their clinical practice (Fig. 4).

The participants’ increased knowledge on viral hepatitis was evident in their quiz scores (Fig. 5). The overall average pre-test score was 2.63 ± 0.29 while the overall average post-test score was 7.09 ± 1.90. Moreover, participants’ session scores showed significant improvement between the pre- and post-test scores (p < 0.001).

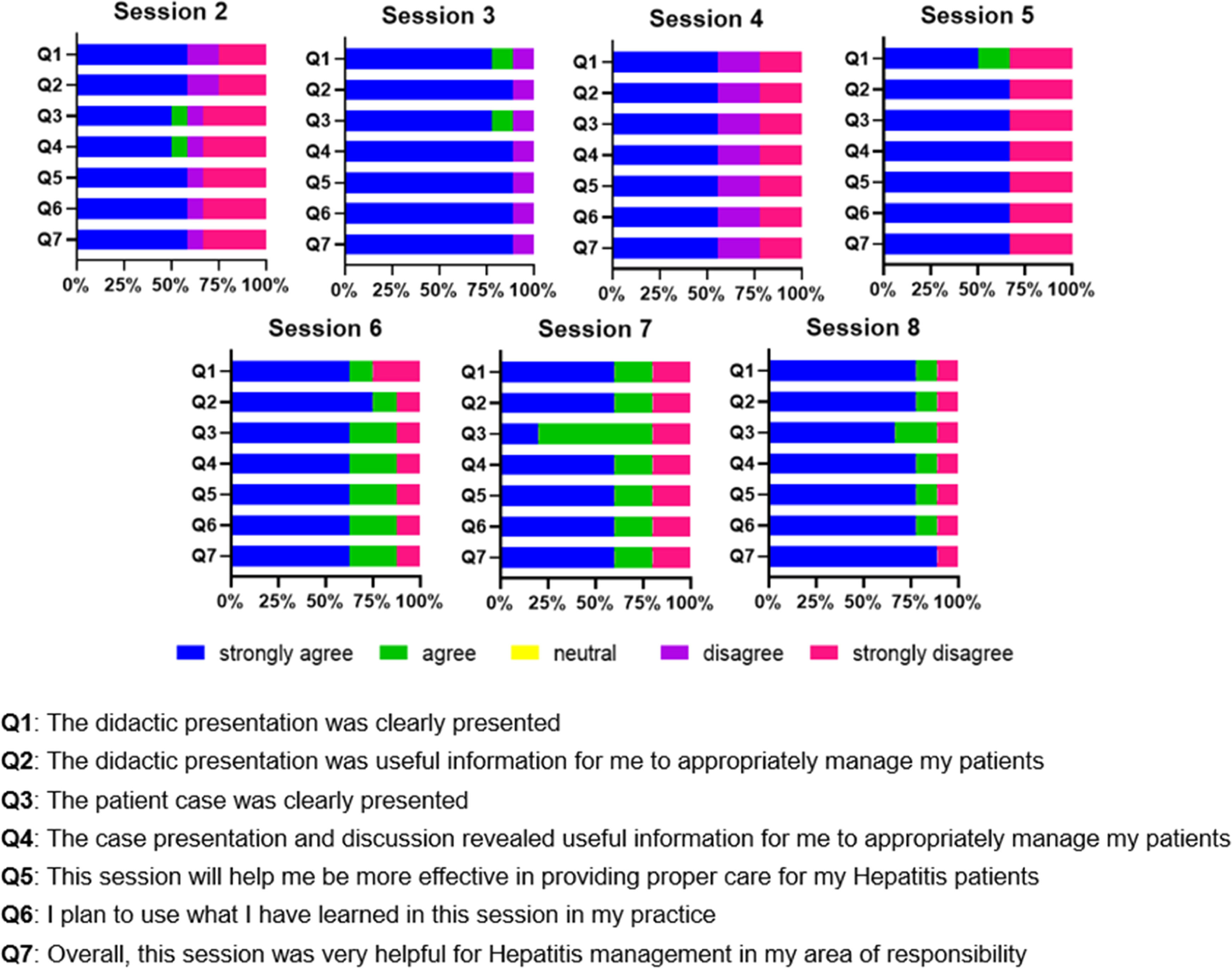

3.2Telementoring/HepTalksThere were 13 physicians who participated in the telementoring sessions. The participants came from different localities in the Central Luzon Region (Region III) (Supplementary Fig. 1). The participants gave an overall positive evaluation of the telementoring sessions (Fig. 6). The majority (63%) strongly agreed that the didactic presentations were clear. Similarly, 69% of the participants strongly agreed that the didactic presentations were helpful in managing patients. Regarding the case presentations, 57% of the participants strongly agreed that the cases were clearly presented, while 66% strongly agreed that the cases were useful in managing patients. Moreover, 67% of the participants strongly agreed that the sessions would help them to provide better care for hepatitis patients, and the same percentage strongly agreed that they would apply what they learned in their practice. Finally, 69% of the participants strongly agreed that overall, the sessions were helpful in managing hepatitis in their geographic area of practice.

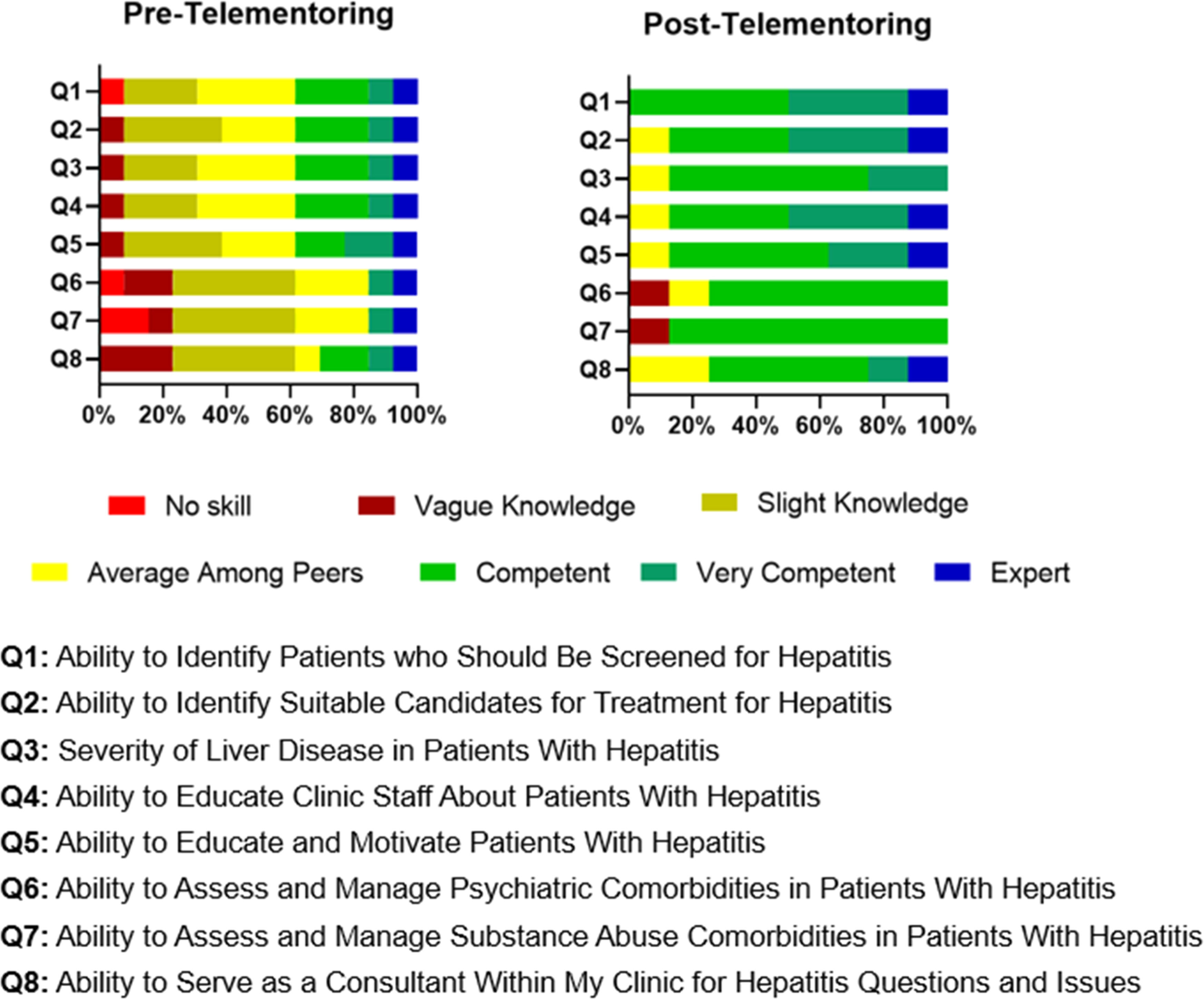

Self-assessment by the telementoring participants showed improvements in their knowledge and skills on viral hepatitis management (Fig. 7). At the start of the telementoring sessions, a majority of the participants reported having little to “no skills”, or being only “average among their peers”, in managing viral hepatitis. However, following the program, the post-telementoring survey revealed that most participants now consider themselves to be “competent”, and in some cases even “expert”, in their ability to manage viral hepatitis. These results suggest that the telementoring program was effective in transferring knowledge and skills to primary care providers, thus improving their capacity and confidence to manage chronic viral hepatitis cases.

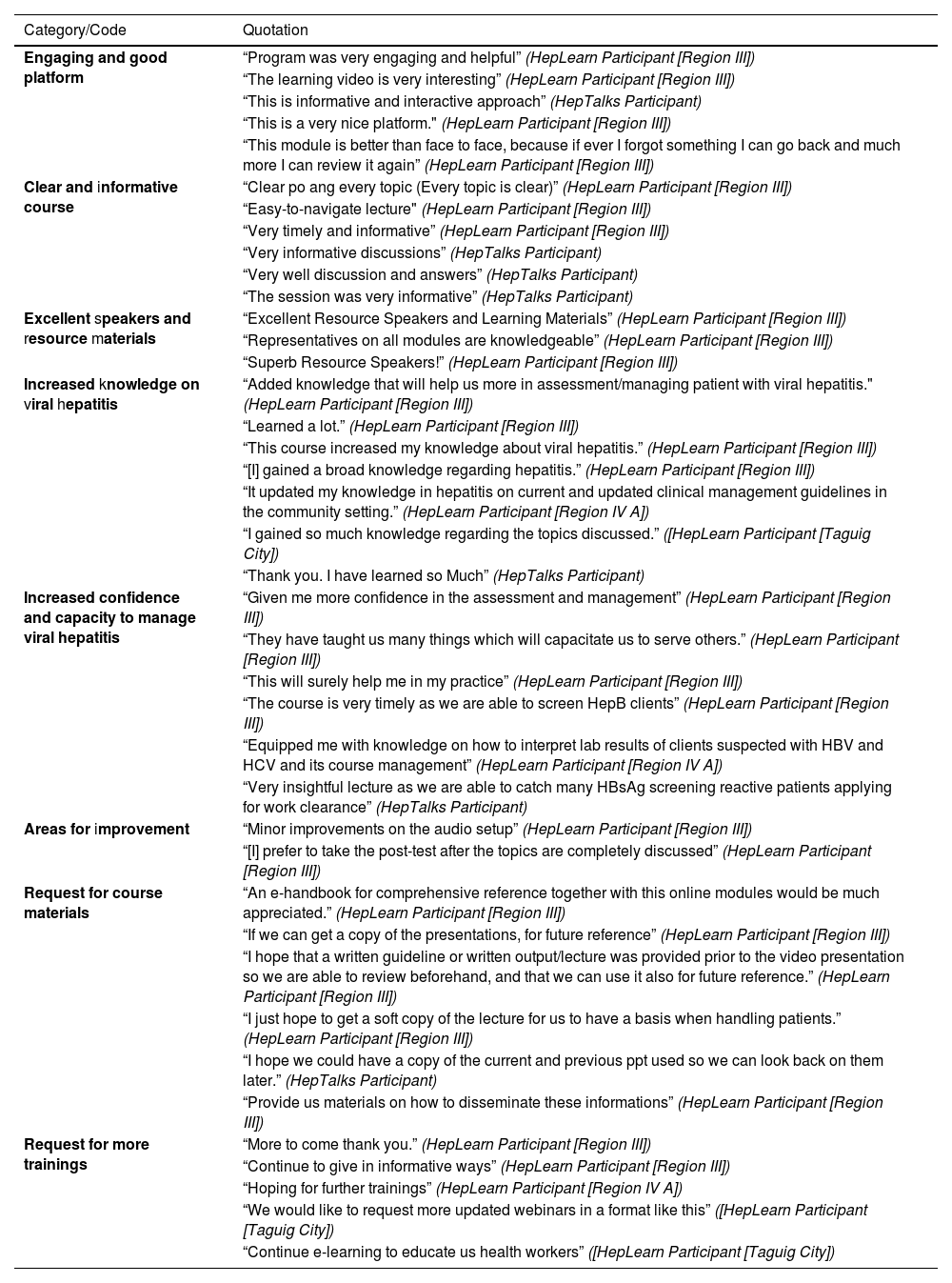

3.3eLearning feedback and commentsThe eLearning study received positive feedback from participants, as indicated in Table 1. Several participants praised the engaging nature of the platform and its effectiveness in delivering learning. One participant from Region III stated, “This module is better than face-to-face, because if ever I forgot something I can go back and much more I can review it again.” Others commended the course content for its clarity and informativeness, with a participant [from Region III] describing the lectures as “easy-to-navigate lecture.” The speakers, lecturers, and resource materials were also commended as exemplified by one comment: “Excellent Resource Speakers and Learning Materials.”

Quotations from the feedback and comments of the HepLearn and HepTalks participants.

Participants also shared that the eLearning course significantly enhanced their knowledge of hepatitis and increased their confidence in managing viral hepatitis. A participant from Region IV A attested, “It updated my knowledge in hepatitis on current and updated clinical management guidelines in the community setting”. Similarly, in the HepTalks session, a participant remarked after a talk on employment and Hepatitis B, “Very insightful lecture as we are able to catch many HBsAg screening reactive patients applying for work clearance.”

While feedback overall was positive, participants provided suggestions for improvement, particularly in the technical aspects of the course. A participant from Region III noted the need for minor audio setup improvements, and another participant in the HepLearn session expressed a preference for taking the post-test after a complete discussion of the topics.

Participants also expressed a desire for access to course materials. One participant in the HepLearn session commented, “I just hope to get a soft copy of the lecture for us to have a basis when handling patients.” This sentiment was echoed by another participant who requested, “I hope that a written guideline or written output/lecture was provided before the video presentation so we are able to review beforehand and that we can use it also for future reference.”

Additionally, several participants expressed their enthusiasm for more training sessions, particularly in the current eLearning format. A participant in the HepLearn session stated, “Continue e-learning to educate us health workers”. Another participant shared a similar sentiment, requesting, “We would like to request more updated webinars in a format like this.”

4DiscussionThis study describes the implementation of a pilot eLearning initiative comprising a computer-based training and telementoring program for viral hepatitis care in public primary care settings. Overall, the training curriculum and telementoring program were well-received by the participants, as indicated by survey results. The program format engaged participants' attention and increased their knowledge of hepatitis management. In addition, participants demonstrated improved technical knowledge, as evidenced by their pre- and post-test scores.

The improved technical knowledge of the participants for viral hepatitis management attests to the utility of eLearning as a mode of transferring knowledge to assist primary care providers in patient management. Several countries have successfully implemented their own computer-based learning initiatives for various diseases [22–25]. For instance, Project ECHO which was originally developed in New Mexico, was successful in improving the management of Hepatitis C in their country. The study increased knowledge of participants and improved access to health care in remote locations [23].

Despite the positive feedback from participants, a large number of them were unable to complete the learning module. Future implementation of eLearning initiatives should include an effort to engage those who did not complete and systematically determine reasons for non-completion. Previous research identified several barriers to the completion of eLearning modalities. The main barriers reported in the literature included the lack of time and scheduling difficulties for healthcare professionals due to their heavy workloads and busy schedules [26,27]. In many low and middle-income countries, shortage of healthcare personnel is a daily reality with heavy workloads especially in the public health sector [28–30]. These barriers can be overcome by providing incentives including but not limited to providing protected time for completion of eLearning modules, and providing continuing education credits [26,31]. While we provided continuing education credits, it was not offered concurrently with the course and may have affected the completion rates. Moving forward, the provision of concurrent continuing education credits with the start of the course should be implemented.

One of the major issues that was encountered during the eLearning initiative was the poor internet connection. According to the Internet Society Foundation, the Philippines ranks 1st in South East Asia, and 7th worldwide in terms of internet poverty (an index measuring quality, quantity and affordability of internet access in a country) [32]. The country records median download speeds of 71.85 Mbps, which ranks 63rd in the world [33]. Several studies evaluating electronic learning modalities in the Philippines ranging from secondary education to medical education, have consistently identified poor internet connection as a barrier to learning [34–38]. Coordination among government agencies, especially between the Department of Health and the Department of Information and Communications Technology, to enhance internet access across the country, especially in healthcare facilities, should be part of any eLearning program implementation.

From the analysis of the qualitative data of the survey, the eLearning initiatives were not only effective but highly appreciated. In fact, in their evaluations, many of the participants have requested additional trainings and updates and for the telementoring program participants, they expressed anxiety that the pilot study was ending. The comments for more training and updates on knowledge highlight the unmet needs in viral hepatitis care in the primary setting. Future models of care for viral hepatitis care in the primary setting should include eLearning initiatives as a key strategy in their implementation.

Future plans for the study team include the submission of the CBT/HepLearn module to the DOH Academy for its inclusion in its course offerings. This will allow expanded access to and ensure the sustainability of the viral hepatitis eLearning initiative. Moreover, the process of multisectoral collaboration in developing and implementing the CBT/HepLearn and telementoring/HepTalks in viral hepatitis care in the primary care setting can serve as the template for the development of similar eLearning initiatives in other disease conditions of public health concern.

4.1Limitations and strengthsThere are a few limitations to the study. As this was a pilot implementation study and was time-limited, service delivery and clinical outcomes such as the number of patients treated, linked to care, retained in care, and controlled or cured from viral hepatitis were not assessed, as these outcomes require a longer observation time for impact to be apparent. The lack of comprehensive baseline data collection from non-completers of the course prevented formal comparison between completers and non-completers, which may introduce selection bias in our results. Participants who completed the program may have been more motivated or had better resources than those who did not complete it. Additionally, the small sample size for HepTalks limit the generalizability of the results. The study also did not incorporate an analysis of the cost-effectiveness of the eLearning initiatives. eLearning initiatives have been shown to be cost effective in viral hepatitis management by the Project ECHO Group [39]. However, a study to analyze cost-effectiveness localized to the Philippines, will be important to convince policymakers to allocate resources to eLearning initiatives. Another limitation is that the eLearning participation was the lack of strong implementation of an administrative directive. This led to deprioritization of the training amid the routine workload of health workers. This, combined with challenges in digital infrastructure, constrained engagement and completion rates.

Despite these limitations, the study had several key strengths (1) successful implementation across two diverse regions demonstrating scalability, (2) feasibility of digital delivery in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with limited resources, (3) collaborative approach involving multiple stakeholders, and (4) practical applicability to real-world primary care settings. The study demonstrated acceptability of the eLearning initiatives. This, in addition to the significant improvement in provider knowledge and clinical confidence in viral hepatitis care highlight the strong potential of the strategy. Future implementation research should focus on evaluating health system and patient-level outcomes, assessing cost-effectiveness in the local context, and exploring mechanisms to institutionalize participation, such as through stronger administrative policies or incentives. This would strengthen the evidence base and support scaling the intervention across other regions in the Philippines.

5ConclusionsThe use of eLearning is a key strategy for the global goal of eliminating viral hepatitis in 2030. There are very few specialists available in low and middle-income countries such as the Philippines that the only way to elimination of viral hepatitis is through building capacity for its screening, diagnosis, and management in the primary care setting. eLearning not only improves access to care where care is needed but also increases the quality and safety of care, brings efficiency to healthcare systems, enhances information flow, and reduces the stigma associated with the disease. With the rapid proliferation of AI technology use in all aspects of health, the incorporation of AI in eLearning initiatives can also be explored in future studies.

FundingThis study was partly supported by a grant from Gilead Sciences Inc. Gilead Sciences Inc. has had no input into the writing of this manuscript.

Availability of data and materialsThe study data could be made available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Author contributionsJO, GH - Data curation, conceptualization. JO, GH, EO - Formal analysis. JO, GH - Funding acquisition. All - Investigation. JO, GH - Methodology. JO, GH, JS - Project admnistration, Resources. JM - Software. JO, GH - Supervision, Validation, Visualization. JO, GH, EO - Writing-original draft. ALL - Writing-review & editing.

None.