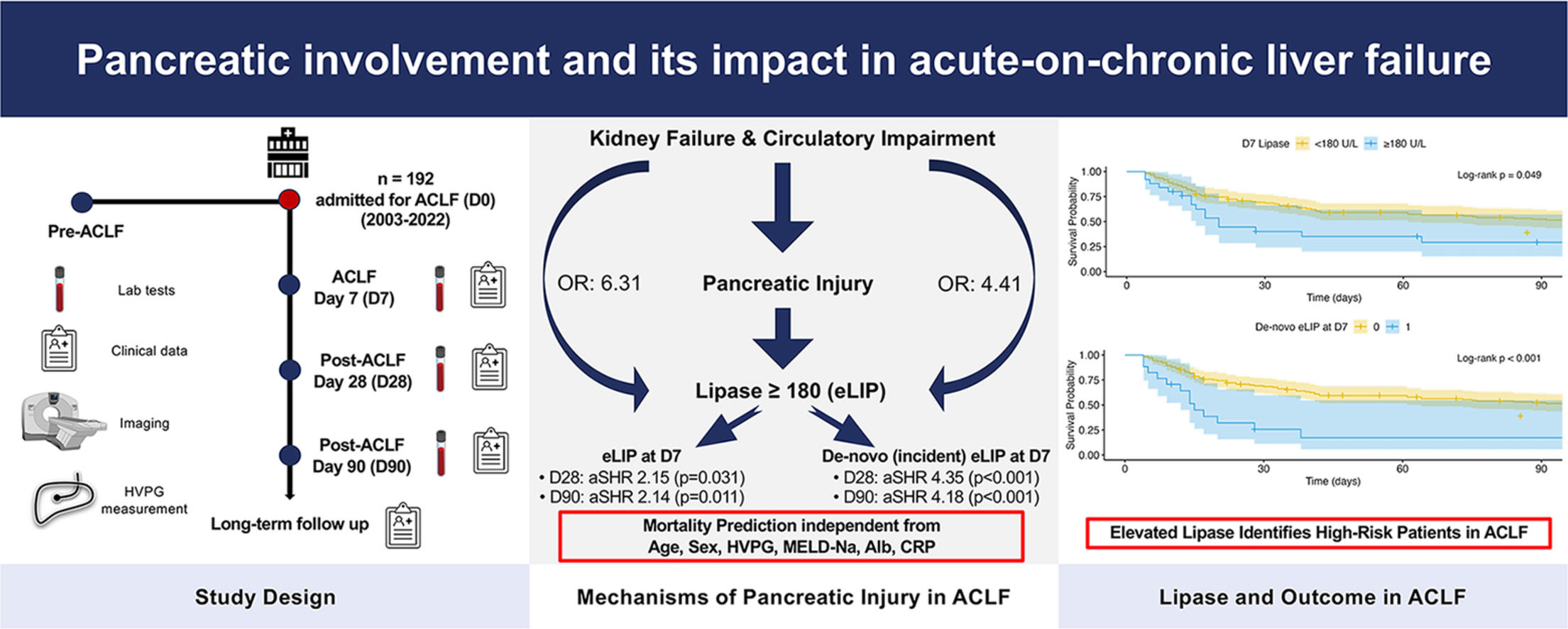

Acute pancreatitis in the context of acute liver failure (ALF) was first documented in 1973 [1]. Over the following decades, several studies have reported on patients with ALF developing pancreatic injury – ranging from pancreatic enzyme elevations to clinical pancreatitis – underscoring a notable link between ALF and pancreatic injury [2–5]. More recently, elevated pancreatic enzymes, particularly hyperlipasemia, was reported in up to 20 % of patients with liver failure, serving as key indicator of pancreatic involvement in this setting [6]. Compared to ALF, studies on the role of pancreatic damage in acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) are scarce. ACLF is a distinct syndrome arising from acute decompensation (AD) in patients with cirrhosis, characterized by (extrahepatic) organ failure and high short-term mortality [7]. Systemic inflammation, immune dysregulation, and other precipitants such as bacterial infections or severe alcoholic hepatitis are well-recognized drivers of ACLF [7,8]. These hallmarks and accompanying factors – particularly hemodynamic compromise, metabolic derangements and alcohol abuse[9] – are also known risk factors for pancreatic injury, yet clinical data of pancreatic involvement in ACLF remain limited.

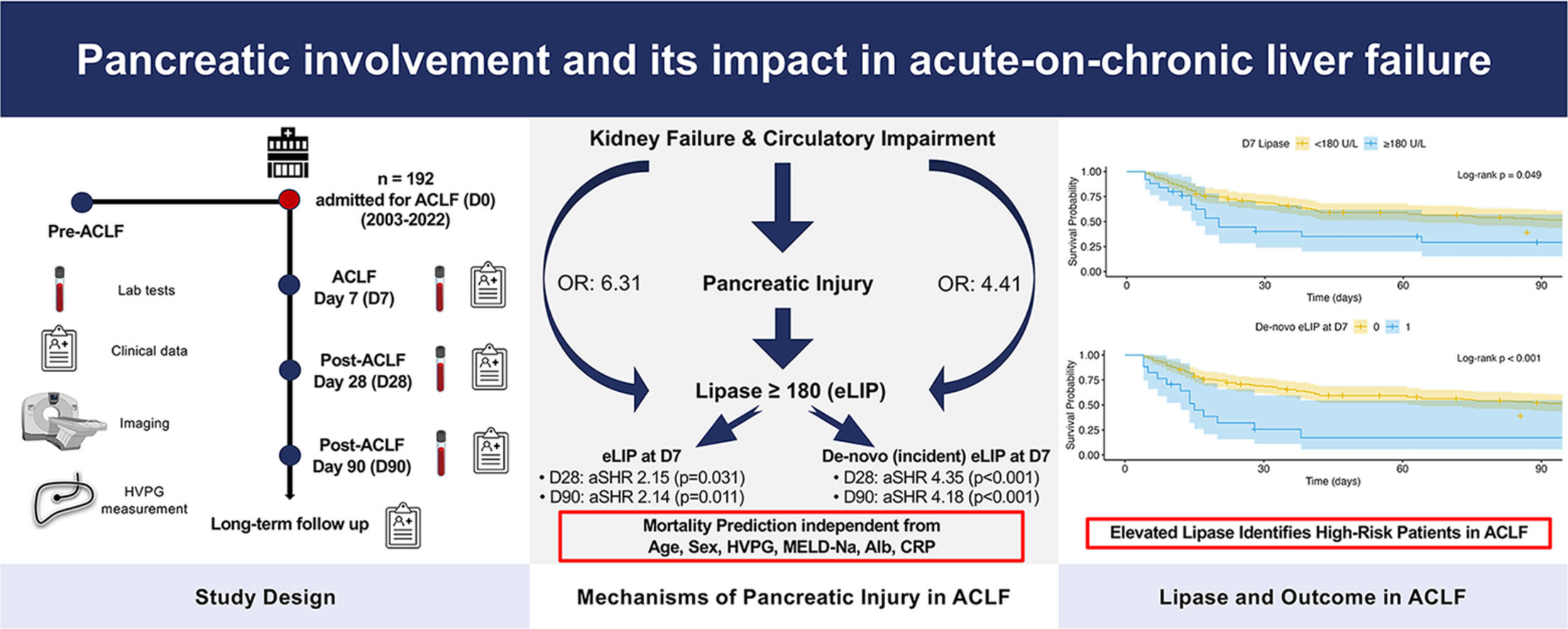

This study aimed to address these gaps of understanding the clinical relevance of pancreatic injury in ACLF by analyzing the prevalence of elevated pancreatic enzymes and its impact on clinical outcomes in ACLF. Furthermore, the associations between pancreatic enzyme elevations and different clinical phenotypes of ACLF were analyzed to provide a foundation for future research into its pathophysiology and therapeutic implications.

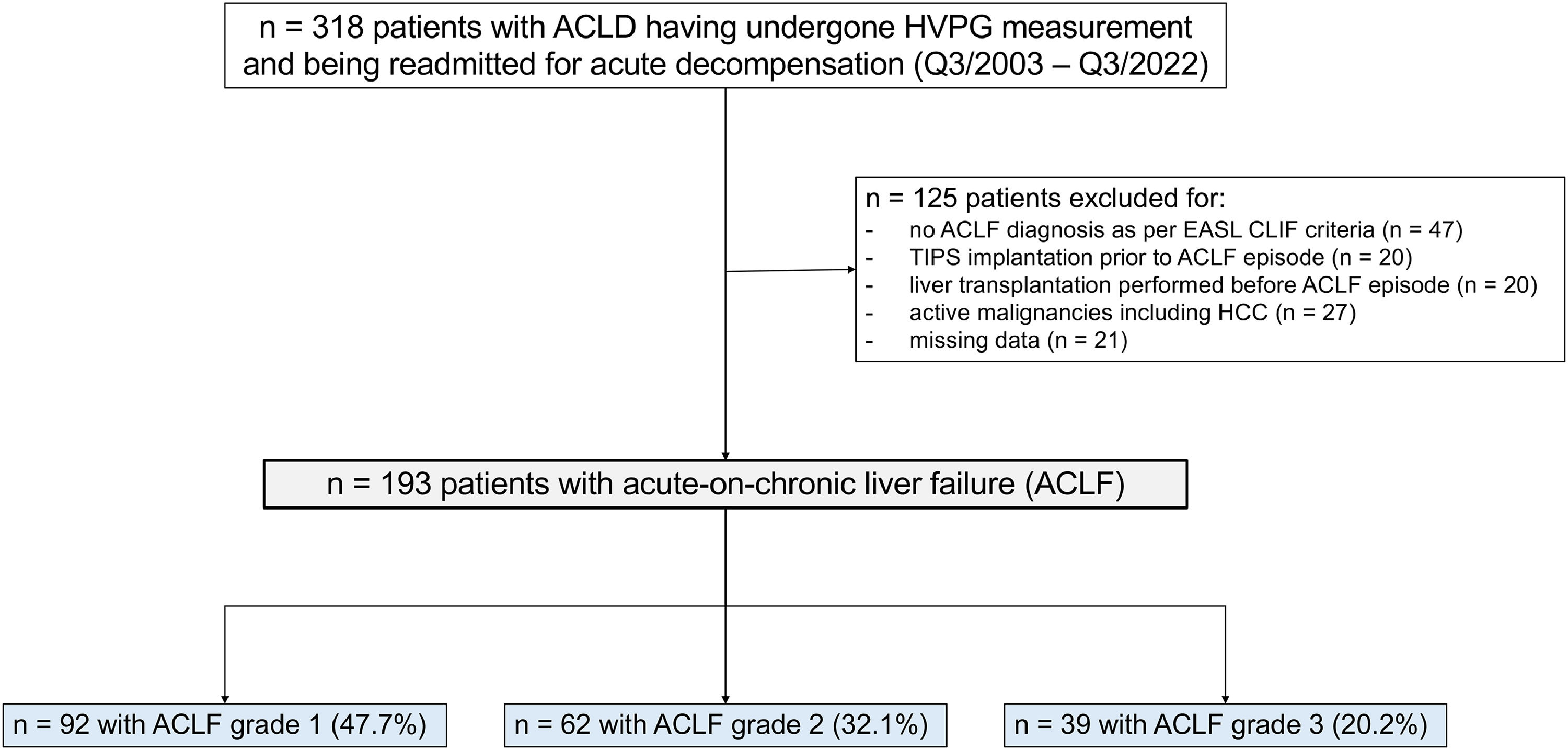

2Patients and methods2.1Patient selection and study designThis retrospective, single-center study included consecutive patients with advanced chronic liver disease (ACLD), defined as hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) ≥6 mmHg, liver stiffness (LSM) ≥10 kPa, or F3/F4 fibrosis on histology, who underwent hepatic vein catheterization and were admitted to the Vienna General Hospital between November 2003 and November 2022 fulfilling the European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure (EASL-CLIF) diagnostic criteria for ACLF[10]. Exclusion criteria included: (i) orthotopic liver transplantation (LT); (ii) transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement; (iii) a diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) prior to ACLF diagnosis. In addition, patients with missing data on serum lipase or (alpha-)amylase at ACLF diagnosis and on day 7 after diagnosis were excluded.

Clinical, laboratory, hepatic hemodynamic, transient elastography and radiologic parameters were collected from patients' medical records, as available, at the following timepoints: at the last visit between 1 and 12 months prior to ACLF diagnosis (pre-ACLF), at ACLF diagnosis (D0) and at days 7 (D7), 28 (D28), and 90 (D90) after ACLF diagnosis. Narrow intervals for each timepoint were defined as follows: data for D0 were collected from 2 days before to 2 days after diagnosis, D7 from 4 to 10 days, D28 from 21 to 35 days, and D90 from 60 to 120 days post-diagnosis.

The upper limit of normal (ULN) for pancreatic lipase and alpha-amylase was set at 60 U/L. Elevations of these enzymes ≥3 times the ULN (i.e. ≥180 U/L) are referred to as elevated lipase (eLIP) or elevated alpha-amylase (eAMY), respectively.

2.2Diagnostic criteria of ACLFThe diagnosis of ACLF was based on the EASL-CLIF criteria[10]. Patients with single kidney failure or a single organ failure combined with either renal dysfunction (serum creatinine ≥ 1.5 mg/dL) or West Haven grade 1–2 hepatic encephalopathy were classified as ACLF grade-1. Patients with two organ failures were categorized as ACLF grade-2, while those with three or more organ failures were classified as ACLF grade-3.

2.3HVPG measurement and LSMHVPG measurements were performed under fasting conditions following standardized guidelines [11]. After local anesthesia, central venous access was achieved through the internal jugular vein, and a hepatic vein was cannulated to record free and wedged hepatic venous pressures, each measured at least three times. HVPG was calculated as the difference between wedged and free pressures, with the final value representing the mean of these triplicate readings. Liver stiffness was assessed using vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE) with a FibroScan® device (Echosens, Paris, France) in accordance with established protocols [12,13].

2.4Assessment of routine laboratory parametersRoutine laboratory tests and biomarker analyses were performed by the ISO-certified Department of Laboratory Medicine at the Medical University of Vienna, using commercially approved methods for clinical use and blood sample analysis.

2.5Determination of pancreatic lipase and alpha-amylase levelsPancreatic lipase concentrations were determined using an enzymatic kinetic assay, whereas alpha‐amylase was measured using an enzymatic colorimetric method. Importantly, the analytical methods for both enzymes remained unchanged throughout the entire study period.

2.6Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were conducted using R 4.4.0 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR), depending on the distribution, which was assessed using normality plots, Q-Q plots and the Shapiro-Wilk test. One-way ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare parametric and non-normally distributed data, respectively. Post hoc analyses were performed using Tukey’s test for ANOVA and Dunn’s test for Kruskal-Wallis results to account for multiple pairwise comparisons. Correlations between continuous variables were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s chi-squared test with Yates’ continuity correction or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

Follow-up duration was estimated using the reverse Kaplan-Meier method[14]. Prognostic impact of pancreatic enzyme elevations was assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression models. Multivariable models were adjusted for established prognostic variables (age, sex, HVPG, albumin, C-reactive protein: CRP, Model for End-stage Liver Disease: MELD-Na) at D0 and D7. Models incorporating D7 values were conducted as landmark analysis with follow-up re-defined to begin at D7 naturally incorporating only patients alive at that time point. Additional models were fitted incorporating the CLIF-C-ACLF score[15] and adjusted only for sex and HVPG to avoid overfitting. Univariable logistic regression models were used to cross-sectionally identify factors associated with elevated lipase levels at ACLF diagnosis or D7. Survival was further analyzed via Kaplan-Meier survival models, with group comparisons performed using the log-rank test with post-hoc pairwise comparisons being adjusted for multiple testing using the Bonferroni correction, where applicable.

Cox proportional hazards and Kaplan-Meier survival models were conducted by utilizing the ‘survival’-package (v3.7–0)[16].

2.7Ethical aspectsThis study adhered to the principles outlined in the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its subsequent amendments and approved by the local ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EK1008/2011 and EK 1262/2017). The requirement for written informed consent was waived by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna due to the retrospective study design.

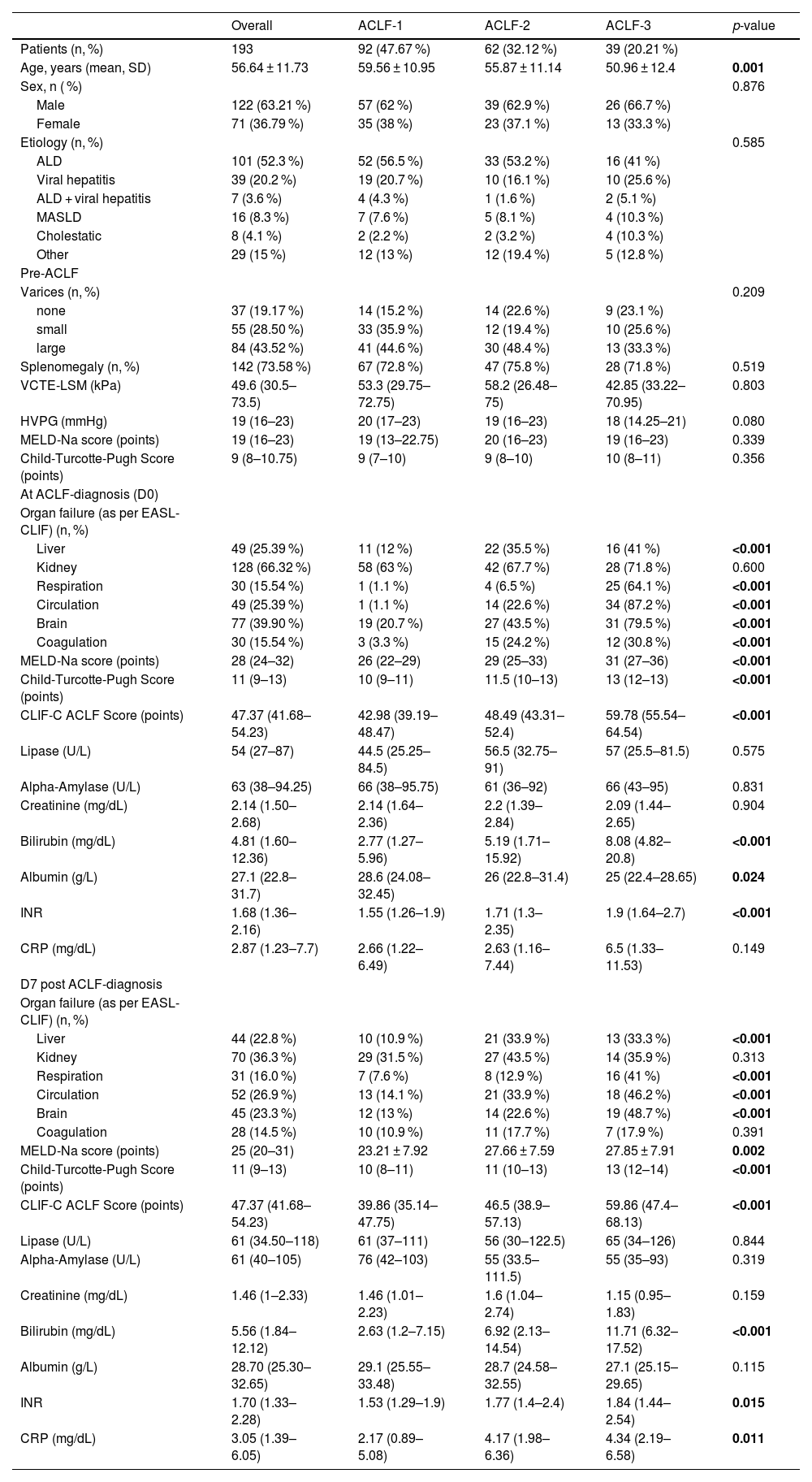

3Results3.1Basic characteristics of the study cohortIn total, 193 patients with a first episode of ACLF admitted to Vienna General Hospital, of whom 92 (47.7 %) had ACLF-1, 62 (32.1 %) ACLF-2, and 39 (20.2 %) ACLF-3, were included in this study. Patients were mostly male (n = 122, 63.2 %) with a mean age of 56.64 ± 11.73 years. The predominant etiology of underlying ACLD was alcohol related liver disease (ALD) (n = 101, 52.3 %) followed by viral hepatitis (n = 39, 20.2 %). Median CLIF-C ACLF, MELD-Na and Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP-) scores upon admission were 47 (42–54), 28 (24–32) and 11 (9–13), respectively. The most common organ failure was kidney failure, affecting 128 patients (66.3 %), followed by brain failure in 77 patients (39.9 %). Liver and circulatory failure were each present in 49 patients (25.4 %), while respiratory and coagulation failure occurred in 30 patients (15.5 %) each. A comprehensive summary of clinical characteristics and laboratory parameters is provided in Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

Data expressed as n ( %), mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (IQR). Between ACLF grades, continuous variables were analyzed using either one-way ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis tests. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. P-values in bold indicate statistical significance.

Abbreviations: ALD, Alcohol-related liver disease; HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; INR, international normalized ratio; MASLD, Metabolic dysfunction- associated steatotic liver disease; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; VCTE-LSM, vibration-controlled transient elastography liver stiffness measurement.

On D0, pancreatic lipase and alpha-amylase levels exceeded the ULN in 84 patients (43.5 %) and 97 patients (50.2 %), respectively, with no significant differences across ACLF grades (p = 0.664 and p = 0.898). Moreover, eLIP was observed in 17 patients (8.8 %) with eAMY present in 14 patients (7.3 %), similarly showing no significant variation between ACLF grades (eLIP and eAMY: p = 0.843 and p = 0.767). Clinical and/or radiologic signs of de novo pancreatitis were observed in only two patients with eLIP at D0 and in one additional patient with lipase levels below the ULN.

On D7, eLIP and eAMY were observed in 25 (15.7 %) and 14 patients (8.8 %), respectively.

At D0, median levels lipase levels were 54.0 U/L (IQR: 27.0–87.0), comparable to pre-ACLF levels (54.0 U/L [36.0–82.0], p = 0.999), increasing insignificantly by D7 (61.0 U/L [34.5–118.0], p = 0.307), before declining significantly by D90 (46.0 U/L [26.8–66.0], p = 0.029). Alpha-amylase levels demonstrated stability throughout the course of ACLF, with no significant changes observed between time points of pre-ACLF until D90 (Supplementary Figure 1).

Notably, pancreatic enzyme elevations were not more pronounced in ALD-related ACLF compared with non-ALD etiologies (Supplementary Table 3). Fig. 1

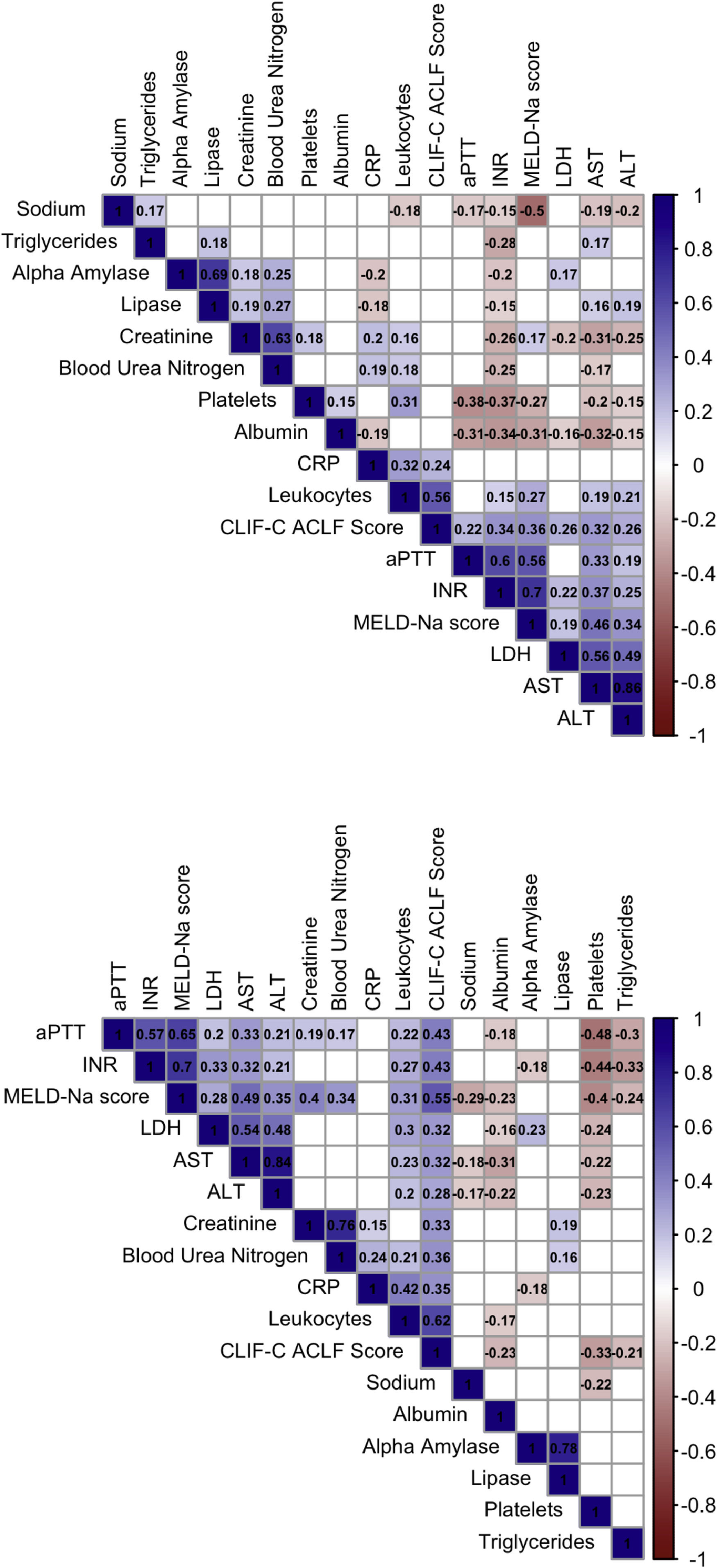

3.3Correlation analysis of pancreatic enzymes at ACLF diagnosisOn D0, Lipase and alpha-amylase were strongly correlated (Spearman’s rho (ρ): 0.687, p < 0.001). Moreover, lipase correlated with blood urea nitrogen (ρ = 0.275, p < 0.001), creatinine (ρ = 0.189, p = 0.009), ALT (ρ = 0.189, p = 0.009), AST (ρ = 0.158, p = 0.031) and triglycerides (ρ = 0.182, p = 0.019), with alpha-amylase showing similar correlations. Both enzymes correlated negatively with CRP (lipase: ρ = −0.181, p = 0.012; alpha-amylase: ρ = −0.195, p = 0.009). Neither lipase nor alpha-amylase levels were significantly associated with liver function, as indicated by the MELD-Na score at D0 or D7 (Fig. 2).

Correlation matrices of pancreatic enzymes, clinical scores and other laboratory biomarkers at D0 and D7.

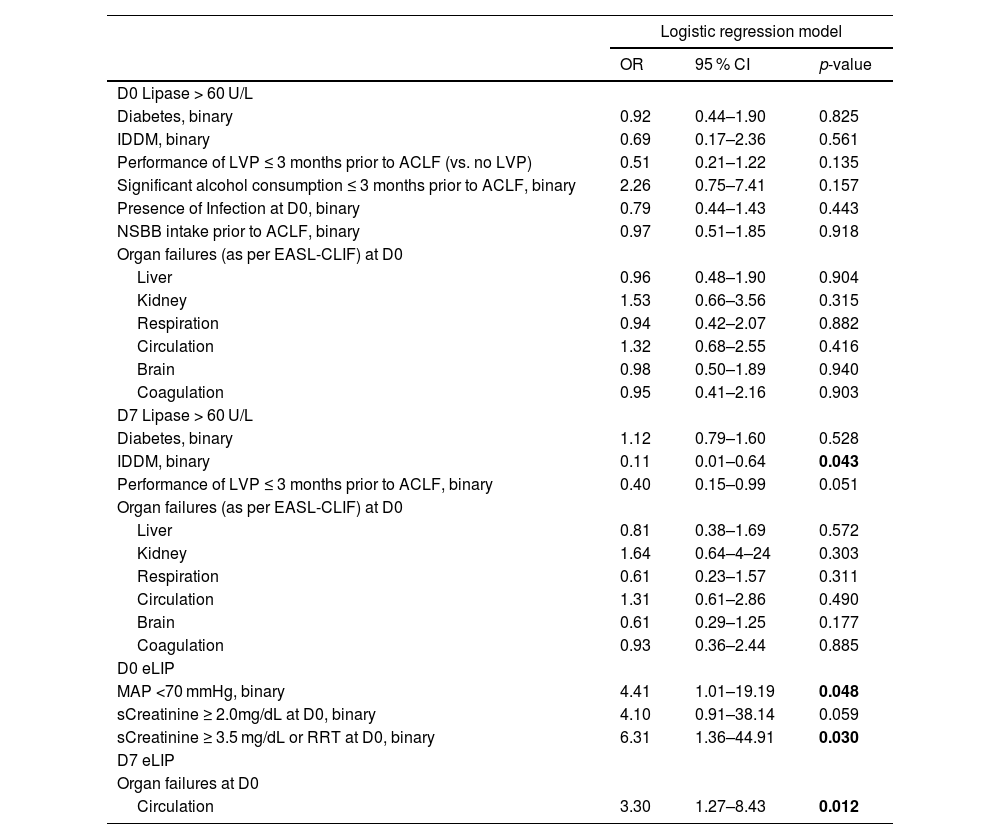

At D0, severe kidney failure was associated with eLIP (OR [vs. no kidney dysfunction] = 6.31, 95 % CI: 1.36–44.91, p = 0.030). Moreover, eLIP at D0 was linked to circulatory dysfunction (mean arterial pressure [MAP] <70 mmHg) (OR [vs no circulatory dysfunction] = 4.41, 95 % CI: 1.01–19.19, p = 0.048). Longitudinally, among patients with circulatory failure at D0, 10 of 34 (29.4 %) showed eLIP at D7, compared to 15 of 125 (12.0 %) without circulatory failure (χ2=4.87, p = 0.027). This association remained significant also in logistic regression modeling (OR [vs no circulatory dysfunction] = 3.30, 95 % CI: 1.27–8.43, p = 0.012). Notably, hyperlipasemia was not associated with non-kidney or non-circulatory organ failures, presence of infection at D0, or precipitating factors such as significant alcohol consumption (≥60 g/day within 3 months prior to ACLF diagnosis) or nonselective beta-blocker use prior to the ACLF episode.

3.5Impact of pancreatic enzymes on ACLF mortality at D28 (and D90)During a median follow-up of 70.2 (7.1–71.9) months, 14 patients (7.2 %) underwent TIPS implantation, 20 patients (10.4 %) received LT, and 157 patients (81.3 %) died. Short-term mortality was significant, with 77 patients (39.9 %) dying by D28 and 104 (53.9 %) by D90.

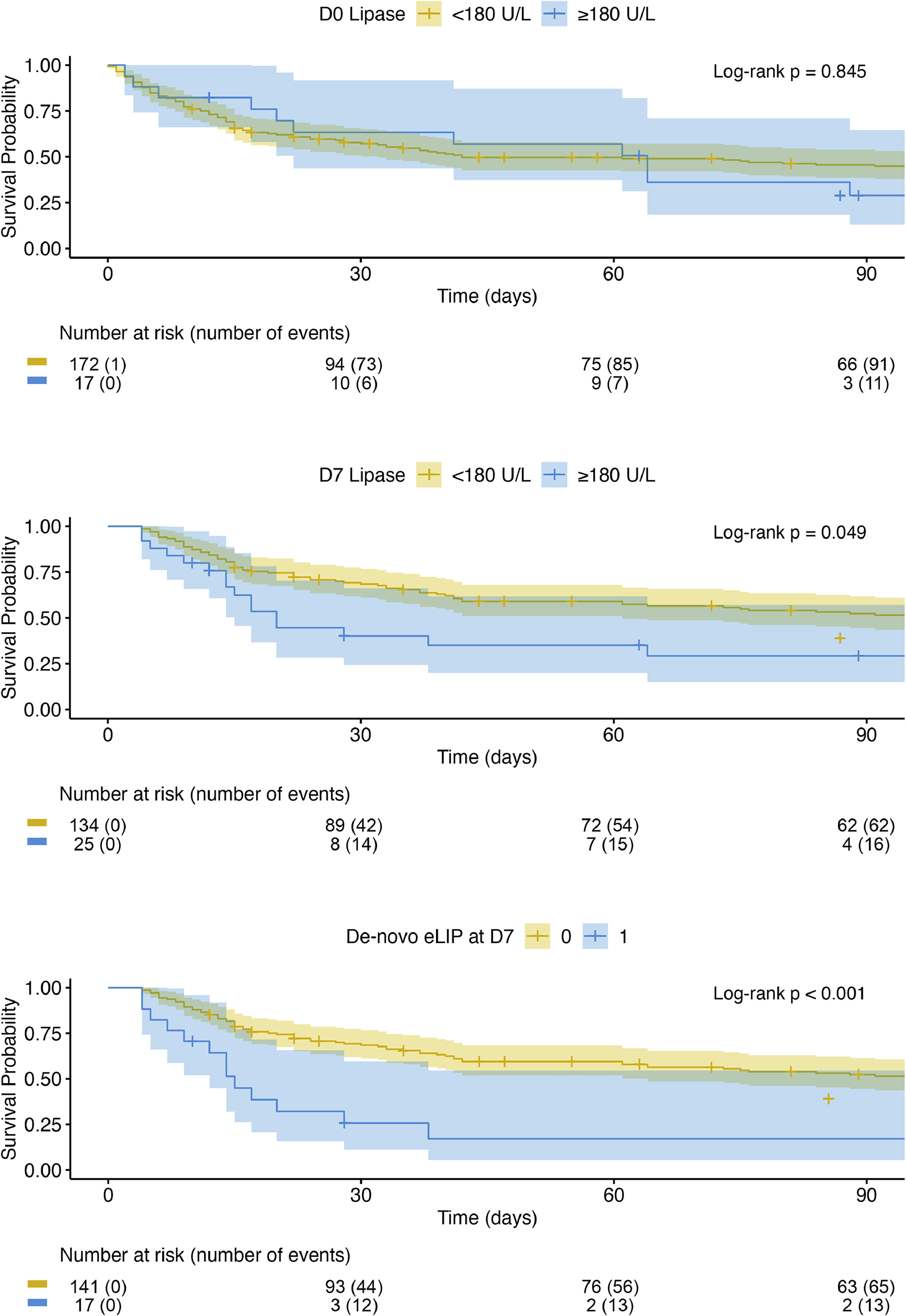

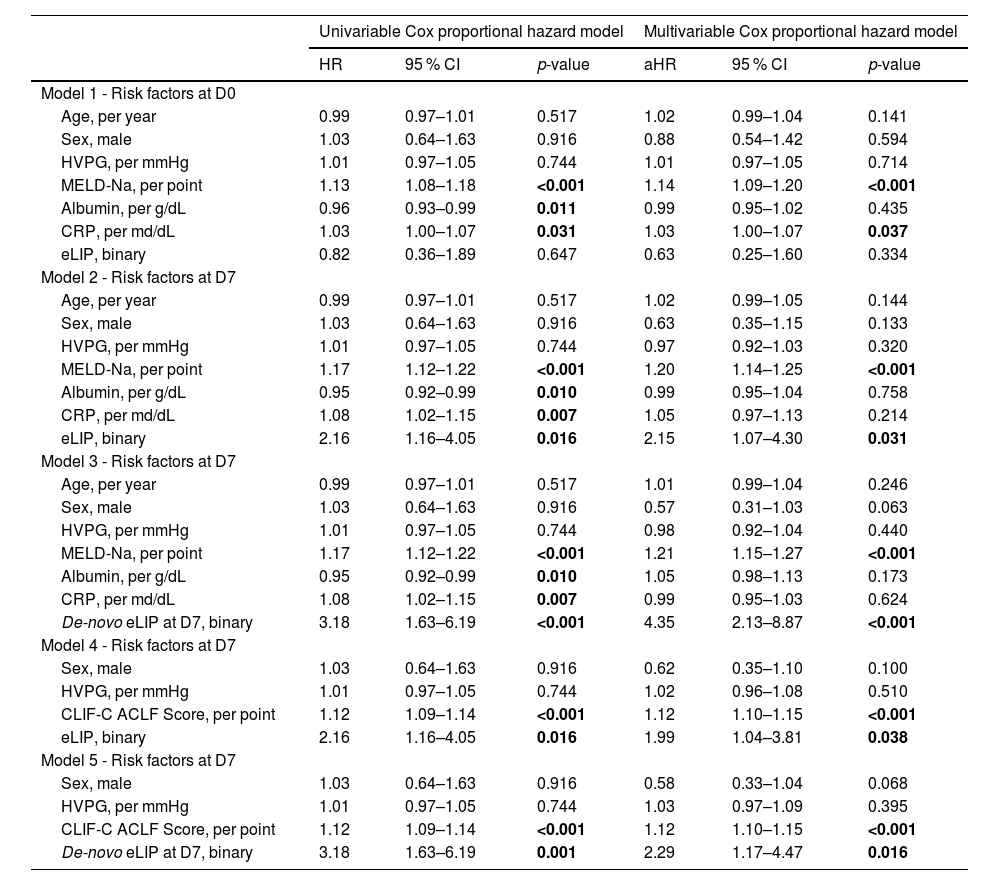

On D0, neither lipase nor alpha-amylase levels, nor their binary classifications exceeding the ULN or meeting the criteria for eLIP or eAMY, were identified as independent risk factors for D28 mortality (for all p > 0.05). By D7, however, eLIP emerged as a significant predictor for D28 mortality in both univariable and multivariable analyses (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]: 2.15, 95 % CI: 1.07–4.30, p = 0.031) (Table 2). This remained the case when adjusting for the CLIF-C ACLF score at D7 (aHR: 1.99, 95 % CI: 1.04–3.81, p = 0.038). Moreover, lipase increasing from <180 U/L at D0 to ≥180 U/L by D7 (de-novo eLIP at D7) was independently associated with a higher risk of D28 mortality, even after adjusting for progression of liver insufficiency reflected by an increase of the MELD-Na score during the same period (aHR: 2.80, 95 % CI: 1.35–5.82, p = 0.006) or the CLIF-C ACLF score at D7 (aHR: 2.29, 95 % CI: 1.17–4.47, p = 0.016). However, after adjusting for progression of the CLIF-C ACLF score, significance was lost (aHR: 1.89, 95 % CI: 0.96–3.73, p = 0.066) (Supplementary Table 1). Table 3

Risk factors for D28 mortality.

Uni- and multivariable Cox proportional hazard models were used to evaluate predictors of D28 mortality. Each model incorporated a single of the assessed risk factors (“interchangeable variates”) alongside indicated fixed covariates. The results are presented as HRs or aHRs, along with 95 % CIs and p values. P-values in bold indicate statistical significance.

Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted HR; CRP, C-reactive protein; eLIP, elevated lipase levels ≥3x ULN; HR, hazard ratio; HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; MELD: model for end-stage liver disease; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Factors associated with elevated D0 and D7 lipase levels.

Logistic regression model results identifying risk factors for elevated lipase levels at D0 and D7. Risk factors analyzed for lipase >60 U/L at D0 were also evaluated for D7 as well as for eLIP at D0 and D7, respectively. However, only significant associations for eLIP are presented, while non-significant results are not shown. Odds ratios for organ failures are shown in reference to absence of respective organ dysfunction. P-values in bold indicate statistical significance.

Abbreviations: ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure; IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; LVP, large volume paracentesis; MAP, mean arterial pressure; NIDDM, non-IDDM, RRT, renal replacement therapy.

These results were also comparable when assessing D90 mortality. However, de-novo eLIP at D7 remained a significant risk factor even after adjusting for an increase in CLIF-C ACLF score (aHR = 2.23, 95 % CI: 1.20–4.15, p = 0.011) (Supplementary Table 2).

3.6SurvivalIn line with the above findings, survival rates did not differ based on the presence of eLIP at D0 (log-rank p = 0.625). However, patients with eLIP at D7 exhibited significantly lower survival (D28 survival: eLIP 40.1 % vs. no eLIP 69.2 %; D90: eLIP 29.2 % vs. no eLIP 52.4 %; p = 0.013). Furthermore, patients developing de-novo eLIP at D7 had especially low survival (D28: de-novo eLIP: 25.7 % vs. no eLIP at D7: 69.2 %, D90: 17.1 % vs. 52.2 %; p < 0.001) (Fig. 3), comparable to those with worsening CLIF-C ACLF score (p = 0.740). 12/17 (70.6 %) patients with de-novo eLIP at D7 demonstrated a progression of the CLIF-C ACLF score from D0 to D7.

ACLF-related mortality was comparable between ALD-related ACLF and those with non-ALD etiologies (log-rank p = 0.225; Supplementary Figure 2).

4DiscussionWhile pancreatic enzyme abnormalities have been extensively studied in ALF, data on their significance in ACLF are limited. This study provides first insights into pancreatic enzyme levels, specifically on the prevalence, dynamics and prognostic impact of elevated (alpha-)amylase and lipase levels in a large cohort of 193 ACLF patients. Additionally, a comprehensive analysis of lipase elevations was performed to elucidate potential pathophysiological mechanisms contributing to pancreatic involvement in ACLF.

Pancreatic enzyme elevations were frequent in our cohort of ACLF patients; however, overt pancreatitis was rare with only three patients (1.6 %) showing corresponding clinical or radiologic features, indicating that most enzyme elevations occurred independently of pancreatitis. Patients presenting with circulatory impairment (MAP <70 mmHg) at D0 showed a 4.4-fold higher risk of lipase levels exceeding 3x ULN (eLIP), while those with grade 3 kidney failure (as per EASL-CLIF criteria) had a 6.3-fold higher risk. Furthermore, circulatory failure at D0 was also associated with eLIP at D7, supporting the notion that pancreatic injury may follow episodes of impaired perfusion. In line with these findings, lipase and alpha-amylase levels both positively correlated with serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, and transaminases (AST and ALT) while CRP levels were negatively correlated with lipase and alpha-amylase, possibly suggesting that pancreatic enzyme release in ACLF occurs largely independent of systemic inflammation.

In such cases where lipase elevation occurs without characteristic abdominal pain or imaging findings, the concept of non-pancreatic hyperlipasemia (NPHL) has been proposed. Here, it is suggested that serum lipase elevations are not primarily driven by pancreatitis but rather result from inflammation of adjacent abdominal organs, impaired renal lipase clearance, and/or reduced hepatic metabolism [17,18]. Prior studies have examined the clinical course of NPHL in relation to acute pancreatitis: Da et al. [19]. identified decompensated cirrhosis (25.5 %) and renal failure (15.7 %) as the most common etiologies of NPHL. More recently, Feher et al. [20]. observed acute kidney failure (33.2 %) and sepsis (27.7 %) as the most frequent conditions in patients with NPHL, whereas liver disease accounted for only 3.5 % of cases. Another study by Pezilli et al. [21]. showed prevalence of pancreatic hyperenzymemia in patients with septic shock, despite the absence of clinical or morphological features of acute pancreatitis.

Aligning with these observations, ACLF fits well within the spectrum of NPHL-associated conditions characterized by hypotension and multiorgan dysfunction, such as sepsis, decompensated cirrhosis and renal failure. Consistently, our results suggest that hyperlipasemia in ACLF also primarily reflects NPHL, possibly arising from circulatory failure-induced hypoperfusion, microcirculatory and kidney dysfunction. Moreover, impaired function of the kidneys, which are especially vulnerable to reduced blood flow, might possibly further contribute to elevated lipase levels through reduced excretion [22,23]. Although hepatic dysfunction has previously been implicated in hyperlipasemia in other settings via reduced metabolism or macro-lipase formation[24], our data do not indicate a significant role of impaired liver function in driving pancreatic injury in ACLF. In fact, no parameters of hepatic synthesis or liver failure exhibited a correlation with hyperlipasemia that would suggest a direct hepatic contribution.

Prognostically, eLIP at D7 emerged as an independent risk factor for D28 mortality in patients with ACLF, also after adjustment for liver function (MELD-Na score) or ACLF severity (CLIF-C ACLF score) at D7. However, when progression of the CLIF-C ACLF score from D0 to D7 was adjusted for, this association was attenuated, indicating that rising lipase levels largely parallel overall disease worsening rather than drive it. In line with this, 70.6 % patients with new onset (i.e., incident) eLIP at D7 also showed an increase in the CLIF-C ACLF score. However, incident eLIP at D7 remained a significant risk factor for predicting D90 mortality, even after adjusting for progression of the CLIF-C ACLF score, underlining its potential prognostic relevance beyond the resolution of ACLF.

These findings might suggest that pancreatic injury, as reflected by rising lipase levels, may serve in the short-term primarily as a marker of worsening systemic illness in ACLF, paralleling overall disease trajectory rather than being a direct driver of disease progression, which aligns with the concept of NPHL. However, persistent associations after adjustment for ACLF severity or progression of eLIP at D7 and de-novo eLIP at D7 with D90 mortality, respectively, indicate that pancreatic injury sustained during ACLF might have a lasting impact on survival beyond the acute phase of ACLF. Thus, lipase levels could provide additional prognostic information beyond established ACLF severity scores, especially when assessing longer-term outcomes. Practically, eLIP at D7 appears to identify a subgroup of patients at particularly high risk of death and could therefore be used as a simple bedside test to recognize those possibly requiring intensified monitoring, early escalation of organ support and timely evaluation for liver transplantation.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. The retrospective and single-center design may limit the generalizability of our findings. The post-hoc application of the EASL-CLIF criteria for ACLF diagnosis and grading may also be influenced by incomplete documentation inherent to retrospective data. Furthermore, retrospective data collection could lead to an underestimation of the true incidence of clinically overt pancreatitis, as the absence of documentation of pancreatitis symptoms or lack of radiological procedures done in critically ill ACLF patients is plausible. Nevertheless, data collection was conducted rigorously, and our findings align closely with previous studies on ACLF characteristics as well as NPHL, supporting the robustness of our results. Finally, the analysis of pancreatic enzyme dynamics included all available parameters at specified time points, potentially introducing immortal time bias, as later time points inherently reflect only surviving patients. Future prospective studies – with standardized imaging protocols and comprehensive biomarker panels – are warranted to validate the prognostic significance of pancreatic enzyme dynamics and to elucidate whether interventions aimed at mitigating pancreatic injury might favorably influence outcomes in ACLF.

5ConclusionsIn summary, this study is the first to investigate pancreatic involvement in ACLF, showing that while overt clinical pancreatitis is rare, dynamic elevations of pancreatic enzymes – particularly lipase – act as biomarkers of worsening systemic illness and are independently associated with higher ACLF-related mortality. These enzyme changes likely stem from a combination of hemodynamic instability, which may trigger pancreatic injury, and impaired renal clearance. Clinically, patients who develop lipase levels ≥180 U/L during the first week of ACLF seem to be at a particularly high risk of mortality and could benefit from intensified monitoring and timely clinical interventions such as escalation of organ support and evaluation for liver transplantation. Lipase may therefore be used as an easy bedside test to identify high-risk patients, and its incorporation into existing risk scores could more accurately reflect dynamics in disease course and may improve outcome prediction in ACLF.

FundingNo financial support specific to this study was received. Some authors (BS, BSH, PS, TR) were co-supported by the Austrian Federal Ministry for Digital and Economic Affairs, the National Foundation for Research, Technology and Development, the Christian Doppler Research Association, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Some authors (GK, BS, BSH, LB, ND, PS, MT, MM, TR) were supported by the Clinical Research Group MOTION, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria - a project funded by the Clinical Research Groups Program of the Ludwig Boltzmann Gesellschaft (Grant Nr: LBG_KFG_22_32) with funds from the Fonds Zukunft Österreich.

Author contributionsGeorg Kramer: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Vlad Taru: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Benedikt Simbrunner: Conceptualization, Data curation, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Lorenz Balcar: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Nina Dominik: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Benedikt Silvester Hofer: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Lukas Hartl: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Mathias Jachs: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Georg Semmler: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Christian Sebesta: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Paul Thöne: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Marlene Hintersteininger: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Mathias Schneeweiss-Gleixner: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Philipp Schwabl: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Michael Trauner: Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Mattias Mandorfer: Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Thomas Reiberger: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Data availabilityThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

G.K. has nothing to disclose. B.S. received travel support from AbbVie, Gilead, and Falk. B.S.H. received travel support from Ipsen. C.S. has nothing to disclose. G.S. received travel support from Amgen. N.D. has nothing to disclose. L.B. has nothing to disclose. L.H. received Travel support from Abbvie. M.H. has nothing to disclose. M.J. has served as speaker and consultant for, and has received unrestricted research grants from Gilead Sciences Inc. M.S.G. has nothing to disclose. P.T. has nothing to disclose. V.T. is funded by the Christian-Doppler Research Association and Boehringer Ingelheim RCV GmbH & Co KG (CD10271603); Romanian Ministry of Education (HG 118/2023) and the Romanian Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitalization (PNRR/2022/C9/MCID/I8). P.S. received consulting fees from PharmaIN and travel support from Falk Pharma. M.T. received speaker fees from Agomab, BMS, Chemomab, Falk Foundation, Gilead, Intercept, Ipsen, Jannsen, Madrigal, Mirum, MSD, and Roche; he advised for AbbVie, Albireo, BiomX, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cymabay, Falk Pharma GmbH, Genfit, Gilead, Hightide, Intercept, Ipsen, Janssen, Mirum, MSD, Novartis, Phenex, Pliant, Rectify, Regulus, Siemens, and Shire. He further received travel support from AbbVie, Falk, Gilead, Intercept, and Jannsen and research grants from Albireo, Alnylam, Cymabay, Falk, Gilead, Intercept, MSD, Takeda and UltraGenyx. He is also a co-inventor of patents on the medical use of norUDCA filed by the Medical Universities of Graz and Vienna. M.M. served as a speaker and/or consultant and/or advisory board member for AbbVie, Collective Acumen, Echosens, Falk, Gilead, Ipsen, Takeda, and W. L. Gore & Associates and received travel support from AbbVie and Gilead as well as grants/research support from Echosens. T.R. received grant support from Abbvie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, Intercept/Advanz Pharma, MSD, Myr Pharmaceuticals, Philips Healthcare, Pliant, Siemens and W. L. Gore & Associates; speaking/writing honoraria from Abbvie, Echosens, Gilead, GSK, Intercept/Advanz Pharma, Pfizer, Roche, MSD, Siemens, W. L. Gore & Associates; consulting/advisory board fee from Abbvie, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, Intercept/Advanz Pharma, MSD, Resolution Therapeutics, Siemens; and travel support from Abbvie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dr. Falk Pharma, Gilead, and Roche.

The financial co-support by the Austrian Federal Ministry for Digital and Economic Affairs, the National Foundation for Research, Technology and Development, the Christian Doppler Research Association, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Clinical Research Groups Program of the Ludwig Boltzmann Gesellschaft is gratefully acknowledged.