Most common indications for liver transplantation.

TRADITIONAL INDICATIONS

Cirrhosis with:

- -

Decompensation (variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, or ascites)

- -

MELD score ≥ 15

- -

Hepatopulmonary syndrome or portopulmonary hypertension

Hepatocellular carcinoma:

- -

Within transplant criteria (e.g., Milan or expanded criteria)

Acute liver failure:

- -

Within transplant criteria (e.g., King College or other)

Inborn metabolic conditions:

- -

Cystic fibrosis with concomitant lung and liver disease

- -

Primary hyperoxaluria type I with significant renal insufficiency

- -

Familial amyloid polyneuropathy

Impaired quality of life:

- -

Persistent and intractable pruritus

- -

Recurrent cholangitis

- -

Polycystic liver disease with severe symptoms

Unresectable benign liver tumors:

- -

With severe complications, symptoms, or malignancy potential (e.g., adenomatosis, hepatic polycystosis, regenerative nodular hyperplasia, Caroli's disease, hepatic lymphangiomatosis, others)

Other hepatic malignancies:

- -

Fibrolamellar carcinoma

- -

Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure:

- -

Without contraindications

Severe alcohol-associated hepatitis:

- -

Not responding to corticoids (or contraindicated) with favorable predictors for post-transplant sobriety

EXPANDED INDICATIONS

Hepatic Metastases from Neuroendocrine Tumors:

- -

Within MILAN NETML

Hepatic Metastases from Colorectal Cancer:

- -

Very selected cases, ideally in the context of clinical trial

Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma:

- -

Very selected cases, ideally in the context of clinical trial

Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma:

- -

Early-stage, unresectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, preceded by neoadjuvant therapy

Most common contraindications for liver transplantation.

Malignancies

- -

Active extrahepatic malignancy

- -

Hepatocellular carcinoma metastatic or AFP > 1,000

- -

Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma outside transplantability criterias

Decompensated disease

- -

Severe cardiopulmonary disease

- -

Uncontrolled sepsis

- -

Active drug abuse

- -

Persistent non-compliance or lack of social support

- -

Technical and/or anatomic barriers to liver transplantation

- -

Irreversible brain injury (in acute liver failure)

- -

ACLF: More than three organ failures according to the CLIF-C organ failure score and/or CLIF-C ACLF score >64

A delayed referral of potential LT candidates represents an important barrier to successful outcomes. Adequate training of physicians to refer early potential candidates to LT could address this limitation. Elevated healthcare costs and restricted medical coverage in many health systems also negatively impact the optimal management of cirrhosis and other related liver diseases [8]. The gap between the need for organs and their availability is widening, as evidenced by waiting list mortality rates that range between 10 % and 50 % across Latin American centers [4,6,9]. Low donation rate is further exacerbated by legislative issues and logistical challenges in converting potential donors into actual donors, including a shortage of intensive care unit beds [1,10].

In this context, the Special Interest Group (SIG) on LT from the Latin American Association for the Study of the Liver (ALEH) aimed to provide guidance in pre- and post-LT management. This guidance is focused on hepatologists, gastroenterologists, internal medicine specialists, surgeons and other healthcare providers involved in the management of LT. This guidance addresses the most relevant areas for perioperative management, including referral criteria, assessment of candidates, and management of patients on the waiting list in Latin America.

2MethodsA scientific board of experts (VM, JM, SG, AV, JP, RZ) from the SIG on LT from ALEH identified clinically relevant questions in three main areas: (a) main referral criteria for LT; (b) the pre-LT evaluation process; and (c) allocation and management of waitlisted patients. Each topic was assigned to a small group of 2 to 4 clinicians with expertise in hepatology and LT, from 14 Latin American countries.

To develop updated evidence-based recommendations, each group searched the literature from January 1990 to December 2024, using PubMed (MEDLINE), Embase, Google Scholar, and LILACS. The search was limited to publications in English and Spanish. The terms "liver transplantation"; "liver transplant indications"; "liver transplant evaluation"; "acute liver failure"; "acute-on-chronic liver failure"; "liver transplant waiting list"; and other relevant items in different combinations helped to identify relevant literature. Reference lists from relevant articles were manually reviewed, and additional key articles were included based on expert recommendations.

Data were also obtained from a web-based survey designed by the scientific board to assess current preoperative LT practices across Latin America. The survey was created using Google Forms and distributed to the SIG on LT members between January and May 2023. Twenty LT centers across 14 countries responded, all but one performing LT (Supplementary Table 1). Results regarding expanding LT indications and contraindications are presented in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

The scientific board reviewed all submissions and recommendations from the working groups. The final recommendations were individually assessed and refined through multiple review rounds until consensus was reached.

3Main referral criteria for LTEarly recognition of LT candidates and timely referral to transplant centers may decrease frailty, perioperative complications, and mortality [11]. In the following paragraphs, we will discuss traditional and novel criteria to consider LT (Box 1).

3.1Decompensated cirrhosisPatients with compensated cirrhosis have an estimated one-year survival rate greater than 90 %, making the prognosis without transplantation favorable. However, once complications develop, such as ascites, variceal bleeding, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatorenal syndrome, or hepatic encephalopathy (HE), survival and quality of life notably decrease at one year. These decompensated patients should be promptly referred for transplant evaluation [12]. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score (and its iterations) is a valuable tool to assess disease severity in cirrhosis. A MELD score ≥ 15 indicates a higher risk of mortality from cirrhosis compared to post-transplant outcomes, warranting evaluation for LT [13–18].

Recommendation:

- •

LT evaluation should be considered in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and/or MELD score ≥15, regardless of the etiology.

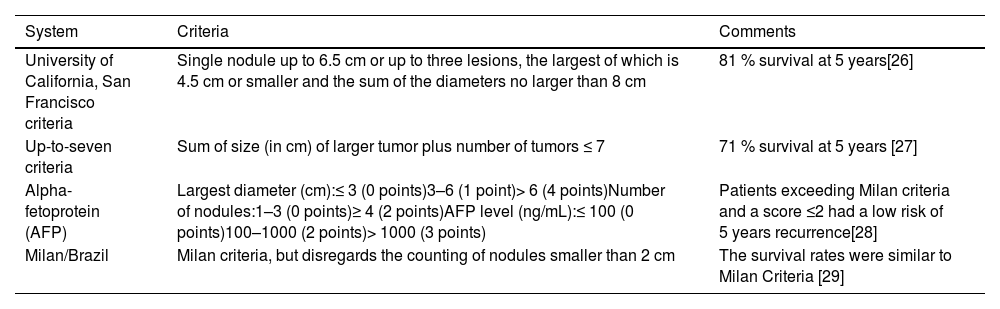

Patients with cirrhosis are at increased risk for HCC, for which should be actively screened every six months with abdominal ultrasound [19] and eventual alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) testing [20]. Early detection will allow access to potentially curative treatments (i.e., surgical resection, LT, and/or locoregional therapies). Diagnosis is made through an abdominal dynamic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) without requiring histopathological confirmation in this population [19,20]. The Milan criteria are the most recognized criteria for LT in patients with HCC, which include a single tumor less than 5 cm or up to 3 tumors each less than 3 cm, without extrahepatic disease [21]. Patients fulfilling these criteria had a four-year post-transplant survival rate of 85 %, with a recurrence rate lesser than 10–15 %, which is comparable to that in patients transplanted for cirrhosis without HCC [21]. However, it may restrict access to LT for some patients who may benefit from the procedure, so additional systems and the possibility of locoregional treatment to reduce tumor burden (downstaging) to Milan or other criteria should also be considered [17,22,23]. Patients with AFP > 1,000 should not be considered for LT except in those with a significant sustained and persistent decline in AFP levels after locoregional therapies [23,24]. In the survey, most countries (93 %) grant supplementary MELD score points to patients with HCC and nine accept expanded criteria for LT [25] (Table 1) (Supplementary Table 2) [26–29].

Expanded criteria for liver transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) use in Latin American countries.

| System | Criteria | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| University of California, San Francisco criteria | Single nodule up to 6.5 cm or up to three lesions, the largest of which is 4.5 cm or smaller and the sum of the diameters no larger than 8 cm | 81 % survival at 5 years[26] |

| Up-to-seven criteria | Sum of size (in cm) of larger tumor plus number of tumors ≤ 7 | 71 % survival at 5 years [27] |

| Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) | Largest diameter (cm):≤ 3 (0 points)3–6 (1 point)> 6 (4 points)Number of nodules:1–3 (0 points)≥ 4 (2 points)AFP level (ng/mL):≤ 100 (0 points)100–1000 (2 points)> 1000 (3 points) | Patients exceeding Milan criteria and a score ≤2 had a low risk of 5 years recurrence[28] |

| Milan/Brazil | Milan criteria, but disregards the counting of nodules smaller than 2 cm | The survival rates were similar to Milan Criteria [29] |

Recommendation:

- •

LT should be considered for patients with HCC within transplant criteria (e.g., Milan or expanded) or when successful downstaging is achieved after locoregional treatment.

ALF, also known as fulminant liver failure, is an uncommon syndrome characterized by a rapid deterioration of liver function in a previously healthy individual, manifested by jaundice, coagulopathy (international normalized ratio [INR] >1.5) and HE, occurring within 26 weeks. Based on the time to onset of HE, ALF is classified as hyperacute (within 7 days), acute (8–28 days) or subacute (>5 weeks). Patients with hyperacute ALF generally have better overall survival and transplant-free-survival than those with subacute ALF [30–33]. The most common etiology of ALF varies across the globe [31,32]. In Latin America, the most common causes of ALF include drug-induced liver injury (DILI), indeterminate, autoimmune hepatitis, and acute viral hepatitis, while acetaminophen is less frequent than in other regions (Table 2) [34–38].

Epidemiological characteristics of patients with acute liver failure in Latin America.

| Variables | Argentina | Brazil | Chile | Perú | Uruguay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 154 | 325 | 168 | 33 | 33 |

| No. of centers | 6 | 12 | 2 | Survey | 1 |

| Authors, et alReference | Mendizabal M[34] | Santos G [35] | Zapata R[36] | Padilla M [37] | Mainardi V [38] |

| Etiology | |||||

| Acetaminophen | 0 % | 1 % | 7.7 % | – | 0 % |

| 1DILI (non-acetaminophen) | 10.4 % | 26 % | 19.5 % | 12.1 % | 6 % |

| Hepatitis A | 2 % | 4 % | 7.7 % | 15.1 % | 3 % |

| Hepatitis B | 30 % | 8 % | 5 % | – | 24.2 % |

| Hepatitis E | – | – | – | – | – |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 26 % | 18 % | 20.8 % | – | 18 % |

| Pregnancy related | 0 % | 1 % | 6.5 % | – | – |

| Wilson's Disease | 0 % | 6 % | 1.7 % | – | 15 % |

| HILI | – | 0.6 % | – | 12.2 % | – |

| Indeterminate | 26 % | 34 % | 25.6 % | 60.6 % | 21 % |

| Other causes | 5.6 % | 1.4 % | 5.5 % | – | 12.8 % |

| Women | 95 % | NA | 75 % | 57 % | 64 % |

| Mean Age (years) | 45 | NA | 39 | NA | 43 |

| LT rate | 53 % | NA | 25.5 % | 12.1 % | 21 % |

| Death without LT | 21 % | NA | 38.6 % | 63.6 % | 30.3 % |

| Improves without LT | 25 % | NA | 35.7 % | 24.3 % | 36 % |

Abbreviations: DILI: Drug-induced liver injury; HILI: Herbal induced liver injury; LT: Liver Transplant; NA: Not available.

If left untreated, ALF can progress to multiorgan failure and death. Emergency LT often serves as the definitive treatment. Early consultation with the nearest LT center is crucial to ensure timely and safe transfer, even before the onset of HE [39,40]. Delayed referrals significantly increase mortality risk, as demonstrated in a recent study from Uruguay [38]. Immediate diagnostic workup should focus on identifying the etiology, assessing severity, determining prognosis and excluding contraindications for LT [30,33,41–43].

Several prognostic models have been developed to identify candidates for LT with ALF (Table 3). The King’s College criteria are among the most widely used, with good specificity but limited sensitivity [41,44]. The MELD score, particularly scores over 30, has demonstrated superior accuracy in predicting mortality, especially in non-acetaminophen-related ALF, and is commonly used in LATAM studies [45]. Determining when a patient is too ill for LT is another relevant aspect. In ALF, the unique absolute contraindication is irreversible brain injury, while other relative contraindications include refractory vasoplegic shock, uncontrolled acute respiratory distress syndrome, severe hemorrhagic pancreatitis, and extensive small bowel ischemia [30]. The decision to proceed with LT should be individualized by an interdisciplinary team, including a hepatologist, transplant surgeon, and intensive care specialist, as ALF is highly dynamic, with rapid changes in patient condition during the waiting period. Living-donor liver transplantation (LDLT) can be an option to shorten the time to transplantation [17].

Different criteria for liver transplantation in individuals with acute liver failure.

Abbreviations: MELD: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; INR: international normalized ratio; HE: Hepatic encephalopathy; ALFSG: Acute Liver Failure Study Group.

Recommendations:

- ●

Early consultation to a LT center should be done in patients with severe acute liver injury (prothrombin time < 50 % or INR > 1.5), even before HE appears, to guide diagnostic work up and to determine optimal timing referral.

- ●

LT candidacy should be determined by an interdisciplinary team.

- ●

LT for ALF patients constitutes an emergency category.

LT for unresectable hepatic metastases from NET should be considered a curative treatment. The best survival outcomes are seen in highly selected patients who meet the Milan criteria for neuroendocrine liver metastasis (Milan NETLM). These criteria include: a) well-differentiated (G1) or moderately differentiated (G2) tumor histology, b) primary tumor drainage via the portal system, c) less than 50 % occupation of the hepatic parenchyma, d) complete resection of the primary tumor and any extrahepatic lesions with stable disease or a good response to treatment for at least 6 months, and e) age under 60 years (relative criterion). Additionally, a Ki67 proliferation index < 10 % is characteristic of well-differentiated tumors, which is favorable in supporting the decision for LT [46,47].

3.5Hepatic metastases from colorectal cancerTechnological advances in imaging, allowing better assessment for extrahepatic disease, along with highly effective chemotherapy treatments, have made it possible to consider LT in very selected patients with isolated, unresectable colorectal metastases which are responsive to chemotherapy. In the SECA-I study, a 5-year survival rate of 60 % was reported, and it identified four clinical factors associated with significantly worse post-transplant survival: tumor diameter > 5.5 cm, carcinoembryonic antigen > 80 mcg/L, time between resection of the primary tumor and LT < 2 years, and progression of metastatic disease during chemotherapy [48]. These elements were incorporated into the Oslo score, which allows stratifying patients based on the number of risk factors (0-4). Furthermore, in a subsequent study (SECA-II), a 5-year survival of 83 % was observed in patients who had shown at least a 10 % response on imaging to chemotherapy and had a diagnosis-to-transplant time of over 1 year [49]. In the TransMet trial, selected patients with permanently unresectable colorectal liver metastases, LT plus chemotherapy with organ allocation priority significantly improved survival versus chemotherapy alone [50]. Evaluation of these patients should be conducted individually by a specialized, multidisciplinary team, and in the setting of clinical trials [23,24].

3.6Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA)The standard treatment for iCCA is surgical resection [51,52]. The benefit of LT in case of unresectability is limited due to the lack of prospective studies. In selected patients (those with cirrhosis, a single lesion smaller than 2 cm, and no vascular invasion), a 5-year survival rate of 65 % after LT has been observed [53]. Consequently, some recent guidelines suggest considering LT in iCCA, ideally within the setting of clinical trials [23,24].

3.7Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (pCCA)Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by LT for selected patients with early-stage (mass < 3 cm in radial diameter and no metastasis), unresectable pCCA is associated with 5-year survival rates of 69 % [54], and has become a standard indication for LT in United States and Europe, with waiting list prioritization similar to patients with HCC [23,24,55].

Recommendations:

- ●

LT should be considered for patients with unresectable NET metastases meeting Milan NETLM criteria.

- ●

LT may be considered in very select patients with unresectable colorectal liver metastases responsive to chemotherapy, evaluated by a specialized interdisciplinary team and ideally within clinical trials.

- ●

In unresectable pCCA, LT should be considered for selected patients with early-stage, preceded by neoadjuvant therapy.

- ●

In unresectable iCCA, LT may be considered in selected patients, ideally within clinical trials.

ACLF represents a severe form of decompensated cirrhosis, characterized by failure in one or more major organ systems (liver, kidneys, brain, coagulation, circulation, respiration) and systemic inflammation, often triggered by acute precipitants. It carries a 28-day mortality rate of 20 % or higher [56,57]. In Western countries, including Latin America, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and Chronic Liver Failure Consortium (CLIF-C) definition is widely accepted [58], although alternative criteria, such as those from Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) [59] and North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease (NACSELD) [60], also exist (Table 4) [61].

Definitions, prevalence, and mortality of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) according to the three main consortiums.

| Characteristics | EASL-CLIF Consortium [58] | NACSELD-ACLF [60] | APASL ACLF Research Consortium [59] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | 31–45 %* | 10–23 %⁎⁎ | 15–65 %⁎⁎⁎ |

| Main Study Cohort | 1,343 patients28 liver units (8 countries)Europe | 2,675 patients14 centersUnited States and Canada | 5,228 patients43 centers (15 countries)Asia-Pacific region |

| Cirrhosis diagnosis | Only applies to patients with cirrhosis | Patients with chronic liver disease, whether cirrhotic or not | |

| Primary driver of acute injury | Non-liver causes (Infection, alcoholic hepatitis, gastrointestinal bleeding, 40 % without an identifiable precipitating event) | Liver causes (alcohol, acute viral hepatitis, drug-induced liver injury, autoimmune) | |

| Failure definition | - Liver: Bilirubin >6 mg/dL- Renal: creatinine >2 mg/dL or use of renal replacement therapy- Coagulation: INR >2.5 or platelet count <20 10˄9/L- Brain: 3 or 4 West-Haven grade of encephalopathy.- Circulation: need for pressor support or terlipressin use.- Respiratory: PaO/FiO2 >100 to <200 or SpO2/FiO2 >89 to <214 | - Liver: not defined- Renal: need for renal replacement therapy.- Brain:3 or 4 West-Haven grade of encephalopathy- Circulation: need for pressor support or a mean arterial pressure (MAP) <60 mm Hg.- Respiratory: need for BIPAP or mechanical ventilation. | - Liver: bilirubin >5 mg/dL and- Coagulation: INR >1.5 or prothrombin activity <40 %; also complicated with the development of clinical ascites and/or- Brain: encephalopathy.- Kidney: Creatinine nor defined- Circulatory: not defined- Respiratory: not defined |

| Diagnosis of ACLF | Any of the following:- Kidney failure-Creatinine ranging from 1.5 to 1.9 mg/dL and/or mild grade 1 or 2 hepatic encephalopathy; plus another failure.- Presence of 2 or more failures | - Presence of ≥ 2 organ failures | - Liver failure plus AARC score model >5 |

| Grades of ACLF | Grade 1: single kidney failure; or single failure of the liver, coagulation, circulation, or respiration with creatinine 1.5-1.9 mg/dL and/or grade 1 or 2 hepatic encephalopathy; or single cerebral failure with creatinine 1.5 - 1.9 mg/dLGrade 2: 2 organ failuresGrade 3: ≥ 3 organ failures | Patients are stratified according to the number of organ failures (0.4) | Liver failure gradingsystem’ based on 5 variables; namely, serum bilirubin, INR,serum lactate, serum creatinine, and HE grad (AARC model)The result of the score defines ACLF grade:-Grade 1:5–7,-Grade 2: 8–10-Grade 3: 11–15 |

| Mortality at 28 days | 33 % | 28 % | 42 % |

| Mortality at 90 days | 51 % | 40 % | 56–68 % |

| Mortality in most severe ACLF grades | 80 % at 28 days in patients with grade 3 ACLF | 77 % at 30 days in patients with four organ failure | 86 % at 28 days in patients with grade 3 ACLF |

| Prognostic accuracy predicting 30-day mortality (AUROC) | 0.83 (95 % CI: 0.79–0.91) | 0.85 (95 % CI: non available) | 0.78 (95 % CI: 0.71- 0.82) |

| Models to predict mortality | Chronic Liver Failure Consortium Organ Failure (CLIF-OF)www.efclif.com | North American Consortium for End-Stage Liver Disease (NACLSELD)www.nacseld.org | APASL ACLF Research Consortium (AARC)www.aclf.in |

Estimated over patients with a first episode of acute liver deterioration due to an acute insult directed to the liver.

Abbreviations: EASL-CLIF: European Association for the Study of the Liver - Chronic Liver Failure; NACSELD-ACLF: North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver- acute-on-chronic liver failure; APASL ACLF:Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver- acute-on-chronic liver failure; PaO2: partial pressure of arterial oxygen; FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; SpO2: peripheral oxygen saturation; INR: international normalized ratio; AUROC: Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic; CI: Confidence interval.

Approximately one-third of Latin American patients admitted for acute cirrhosis decompensation meet ACLF criteria. Among these, half are categorized as grade 1, with the remainder distributed between grades 2 and 3 [62,63]. Another Latin American prospective study (ACLARA) identified alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD), chronic viral hepatitis, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), and immune disorders as common underlying etiologies, with infections, alcohol-associated hepatitis, and gastrointestinal bleeding as frequent precipitants. Native American ancestry and active alcohol use may increase the likelihood of ACLF diagnosis among Hispanic individuals [64].

LT remains the sole curative treatment for ACLF. Around 15–20 % of patients with cirrhosis present ACLF at listing, while one-third develop it while awaiting for LT [60,65,66]. Despite higher perioperative risks and potentially reduced survival after LT, LT significantly improves survival in individuals with ACLF grades 2 or 3, with a reported 1-year post-transplant survival rate exceeding 80 % [65,67–71]. However, retrospective studies highlight biases, and ACLF patients face increased risks of surgical complications, infections, longer intensive care unit (ICU) stays, and readmissions, underscoring the importance of careful candidate selection [67,72].

Patients with ACLF often have high MELD or MELD sodium (MELD-Na) scores, expediting LT access. However, approximately 65 % of ACLF patients exhibit MELD-Na scores below 30 despite high mortality risk [65], revealing limitations in current allocation systems [73]. Prognosis models like CLIF-C and NACSELD scores have been shown to accurately predict short-term survival (Table 4) [74,75]. Societies like EASL recommend prioritizing ACLF grade 3 patients in pilot programs, but further research is needed to refine allocation methods [76].

Identifying candidates too ill for LT remains a challenge. Factors such as lactate > 4 mmol/L, renal replacement therapy, and infections with multidrug-resistant organisms were linked to post-LT mortality in a retrospective European study [68]. Severe frailty, persistent sepsis or uncontrolled infection, pan-drug resistant bacterial infections, respiratory insufficiency (PaO2/FiO2 <150), severe circulatory failure (norepinephrine > 1 mcg/kg/min), lactate levels > 9 mmol/L, and persistent clinical deterioration should be considered contraindications to LT according expert consensus [77]. The novel SALT-M score incorporates factors like age, body mass index (BMI), diabetes, and organ failure to better predict 1-year post-LT mortality and hospital stay length [78]. Patients with more than three organ failures according to the CLIF-C organ failure score or CLIF-C ACLF score > 64 should not be listed until improvement according to EASL guidelines [23]. Prospective data from large multicenter studies like CHANCE (NCT04613921), led by the CLIF-C, are expected to guide future strategies.

Timing of LT is also crucial, and the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) data suggest optimal LT within 7 days of listing [79], minimizing ICU-related complications like muscle weakness and infections [80]. Considering the narrow timeframe, especially in ACLF grade 3, some experts suggest considering extended donor criteria and LDLT in highly experienced centers [76].

3.9Severe alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH)Severe AH (defined by severity scores MELD ≥ 21 [81]) unresponsive to steroid treatment (day 4 or 7 Lille score > 0.45), is associated with a mortality of up to 50 % at 6 months [82]. Consequently, severe AH has emerged as a novel indication for early LT, especially in those fulfilling the following criteria: first episode of liver decompensation, excellent psychosocial status, and a commitment to post-LT abstinence and rehabilitation, as it has demonstrated substantial survival benefits [83–85]. In addition, a recent proposal suggests avoiding steroids in patients with “catastrophic” severe AH (defined as: MELD-Na ≥35 and/or Maddrey’s discriminant function ≥ 100) and advocating for immediate LT referral as first-line therapy in selected patients [86].

Candidates for LT with severe AH require a detailed multidisciplinary psychosocial assessment, to decrease the risk of heavy drinking after LT and optimize post-LT survival [87]. Several predictive scores for sustained alcohol abstinence exist, each with its pros and cons for clinical practice. The QuickTrans study proposed a scoring algorithm to select candidates for early LT, which included somatic criteria (severe comorbidities and prior liver decompensation), global evaluation by an addiction specialist (assessment of psychiatric disease, family support), evaluation by the liver team (patient motivation, medical adherence, insight, support system, alcohol problems in relatives, questions asked by relatives), and a subjective evaluation of the candidate’s adaptability [88].

Recommendations:

- ●

Patients with ACLF 2-3 should be assessed for LT.

- ●

LT futility in patients with ACLF-3 should be evaluated daily by an interdisciplinary team, considering independent predictors of post-LT mortality.

- ●

Patients with ALCF-3 who are candidates for transplantation may be considered for prioritization on the waiting list.

- ●

Patients with severe AH should undergo a thorough evaluation by an interdisciplinary team (including an addiction specialist) to evaluate early LT candidacy.

The process of LT assessment involves the confirmation of the non-reversibility of the patient's liver disease and the absence of alternative treatments that could significantly impact the prognosis, an evaluation of comorbidities and psychosocial issues, and exclusion of contraindications (Box 2). This requires a multidisciplinary approach, led by the hepatologist and involving specialists who are part of the transplant process, such as surgeons and anesthesiologists, as well as supporting specialists like cardiologists, infectious disease experts, nutritionists, social workers, and physiatrists, among others (Table 5) [14–16].

The liver transplant evaluation.

Abbreviations: CT: computed tomography; MR: magnetic resonance; HPV: Human Papillomavirus; PSA: Prostate-Specific Antigen

Specialist liver transplant nurses are key members of the multidisciplinary team involved in pre-transplant evaluation. They lead the coordination of assessments and contribute to patient education and continuity of care. Specific competencies such as clinical knowledge, communication skills, attitude, and motivation are essential to providing comprehensive and safe care for liver transplant patients [89].

The pathway for LT candidate evaluation is described in Fig. 2.

The changing etiology of liver disease, with a predominance of MASLD over hepatitis C, has led to an increasing number of older patients being evaluated for transplantation. Older candidates (65–70 or > 70 years) often present with more comorbidities, higher waitlist mortality, and increased post-transplant morbidity and mortality [90]. However, if carefully selected, the benefits of transplantation can be comparable to those for younger patients. Key factors in the selection process for older candidates include cardiovascular health, functional status, and malignancy risk [91]. However, in some Latin American countries, age limits are set (e.g., 65, 70, or 75 years) due to differences in life expectancy between younger and older recipients in the setting of a population-based transplant benefit policy[25](Supplementary Table 3).

Recommendation:

- ●

Older recipient age is not a contraindication to LT in the absence of significant comorbidities

The increase in the number of MASLD LT candidates has also led to a rise in the number of obese persons being assessed. Obese persons face reduced access to LT, with an increased risk of dropout and mortality in waiting list [92,93]. Perioperative complications are notably higher among obese persons, including biliary and vascular complications, wound infections and dehiscence, overall infections, and extended hospital stays [92,94]. Although there is no universally accepted BMI threshold, a BMI > 40 kg/m² is generally considered a relative contraindication to LT due to increased perioperative risks and reduced graft and patient survival [15]. In Latin America, nearly half of LT centers apply this cutoff when evaluating transplant eligibility [25]. (Supplementary Table 3). Managing obesity and MASLD effectively requires a multidisciplinary, synergistic approach involving hepatologists, dietitians, endocrinologists, psychologists, endoscopists, and surgeons to implement preventive and therapeutic interventions. Defining a center-specific BMI thresholds should take into account local experience, surgical expertise, and access to perioperative support.

Recommendations:

- ●

A BMI > 40 kg/m² is a relative contraindication to LT

- ●

Obese patients require a multidisciplinary approach by an obesity team to achieve the best long-term outcomes.

Chronic liver disease often leads to malnutrition, sarcopenia and progressive functional decline, which can significantly impact transplant success and survival rates [14,96]. Screening for malnutrition and counseling by a dietitian, include correcting misconceptions about restriction of protein and addressing the possible need for enteral or even parenteral feeding prior to LT [15].

Assessment of muscle mass by anthropometric measures, have limitations in patients with cirrhosis due to fluid retention, and also has the inability to distinguish different body compartments, which is particularly relevant in sarcopenic obesity [96]. Nevertheless, a BMI < 18.5 has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality [14,15] and is considered a relative contraindication for transplantation in 11 % of Latin American centers [25] (Supplementary Table 3). Skeletal muscle index by CT analysis is the most consistent and reproducible method to quantify muscle mass in patients with cirrhosis. Because of the risks of exposure to radiation, it is not recommended for its sole purpose, but should be considered when a CT is part of the evaluation in patients in whom assessment of frailty is not feasible (e.g. very acute ill hospitalized patients) [96].

Frailty should be assessed with a standardized tool, and is particularly useful in the ambulatory setting [96]. The Liver Fragility Index (LFI), uses simple tests such as grip strength, chair stands, and balance testing to predict mortality risk [97] and is widely used in Latin American centers. Frail LT recipients (defined by an LFI ≥ 4.5) exhibit higher pre-transplant and post-transplant mortality and greater healthcare utilization [98]. However, transplantation provides a survival benefit across all LFI values, with no identified threshold where post-transplant mortality exceeds pre-transplant mortality [99].

Malnutrition, sarcopenia and frailty should be addressed by targeted interventions [96]. Prehabilitation, which includes physical training, psychological support, and nutritional interventions, has been shown to enhance survival outcomes and decrease health care utilization [100,101]. Osteoporosis is another common complication in patients with end-stage liver disease. Therefore, bone densitometry should be included in the transplant evaluation, along with the assessment of vitamin D and calcium levels, and treatment should be initiated as needed [14,15,17].

Recommendations:

- ●

Candidates should be assessed for malnutrition, frailty and/or sarcopenia, and osteoporosis, with specific prehabilitation interventions provided as necessary, and reassessment periodically.

With the increasing age and prevalence of MASLD among LT recipients, cardiovascular diseases have become a leading cause of morbidity and mortality after LT [102,103]. The aims of cardiovascular assessment are identifying and managing risk factors, and excluding those candidates with significant contraindications like severe coronary artery disease, heart failure, or severe portopulmonary hypertension [104]. All LT candidates should undergo an electrocardiogram (EKG) and transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) [15,23]. Individuals with risk factors for coronary artery disease should undergo additional tests such as cardiopulmonary exercise tests or coronary angiography [15]. Dobutamine stress echocardiography (DSE) shows limited diagnostic accuracy for detecting coronary artery disease (CAD) compared to the gold standard of coronary angiography and offers suboptimal preoperative risk stratification in LT candidates [105–107]. As a result, non-invasive modalities with greater precision are increasingly recommended in recent guidelines. Coronary artery calcium scoring (CACs) has demonstrated superior screening performance, with a positive predictive value (PPV) of 80 % vs. 56 % for DSE [108]. A CACs > 400 Hounsfield Units predicts the need for revascularization and early complications after LT [109]. Cardiac MRI, an operator-independent technique with high reproducibility, allows comprehensive evaluation of cardiac structure, function, and ischemia in a single exam. Finally coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) can detect significant coronary lesions, though its low specificity remains a known limitation—largely dependent on the pre-test probability of CAD, and not specific to LT candidates [110].

The CAD-LT score is a clinical risk tool developed to assess cardiovascular risk in LT candidates. Originally proposed by Rachwan RJ et al., the score was derived from a large cohort of LT candidates who underwent invasive coronary angiography, aiming to identify clinical predictors of significant CAD. It demonstrated good discriminatory capacity and allowed for stratification into low, intermediate, and high-risk categories [111]. A modified version of the CAD-LT score, proposed by Pagano G et al., simplified the original tool while maintaining its predictive accuracy. This version was validated in an independent cohort and offers a practical, low-cost option for detecting patients at risk of significant CAD. While these scores do not replace imaging-based evaluations such as CCTA, they may serve as valuable screening tools, particularly in resource-limited settings, to avoid unnecessary invasive testing in low-risk patients. However, further prospective studies and external validation are needed before routine adoption into clinical guidelines [110].

Cardiac revascularization should be considered in LT candidates with significant coronary artery stenosis prior to transplant. Regular risk assessments, including repeat EKGs and echocardiograms, are advised for waitlisted LT candidates. Evaluations should also address non-ischemic conditions like valvular heart disease, arrhythmias, and pulmonary hypertension, which could impact transplant eligibility [102–104,109].

To evaluate the pulmonary function, lung function tests and a chest X-ray are recommended in all candidates to LT. When hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS) or portopulmonary hypertension (POPH) are suspected, further investigations should be performed (Table 6) [14,15,17,112–114].

Portopulmonary hypertension and hepatopulmonary syndrome.

| Condition | Definition | Suspicion | Confirmatory | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POPH | MPAP >20 mmHg, PVR≥ 3 WU and PAWP≤15 mmHg, in the presence of portal hypertension and excluding other causes [105]. | TTE with a SPAP ≥38 mm Hg and/or dilatation of the right heart cavities [24], or TRV > 2.8 m/s or other signs of pulmonary hypertension[105] | Right heart catheterization | Moderate (MPAP ≥35 mmHg) and severe (MPAP ≥45 mmHg) POPH are predictors of increased mortality post-LT. LT can be considered for POPH patients responding to vasodilator therapy with MPAP < 35 mmHg and PVR < 5 WU, or mPAP 35-45 mmHg and PVR <3 WU. MPAP >45 mmHg despite vasodilator treatment is an absolute contraindication to LT[24,105]. |

| HPS | Hypoxemia due to dilated intrapulmonary vasculature and shunts in the presence of portal hypertension and excluding other causes[106]. | SPO2 <96 % at sea level | Contrast-enhanced TTE: delayed presence of microbubbles in the left heart after intravenous injection (3 or more cardiac cycles after being seen in the right heart)[106] | LT can reverse HPS in most patients, although those with severe HPS (PaO2 <45 mmHg) face higher perioperative mortality[107] |

Abbreviations: POPH: Portopulmonary hypertension; MPAP: mean pulmonary artery pressure; PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance; WU: Woods units; PAWP: pulmonary arterial wedge pressure; TTE: transthoracic echocardiography; SPAP: systolic pulmonary artery pressure; TRV: peak tricuspid regurgitant velocity; LT: liver transplant; HPS: Hepatopulmonary syndrome; SPO2: Peripheral oxygen saturation.

Recommendations:

- ●

Cardiovascular evaluation by a multidisciplinary team, including a cardiologist and an anesthesiologist, should include EKG and TTE.

- ●

Further evaluation of CAD with non-invasive imaging or invasive coronary angiography should be guided by clinical risk stratification tools, such as the CAD-LT score or its modified version.

- ●

If signs of pulmonary hypertension are detected at TTE, a right heart catheterization is indicated to evaluate POPH.

- ●

Respiratory assessment with pulse oximetry, lung function tests and a chest X-ray are recommended

- ●

If SPO2 <96 % at sea level, a contrast echocardiography with bubble study must be done to evaluate HPS.

Evaluating renal dysfunction in patients with end-stage liver disease requires an accurate calculation of the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and the determination of the precise etiology, as these factors impact prognosis both with and without LT [15]. End-stage kidney disease (ESKD) following LT is associated with high morbidity and mortality, which can be mitigated by performing a simultaneous liver-kidney (SLK) transplant in select cases [115]. In 2017, The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network updated the eligibility criteria for SLK transplantation policy (Table 7) [116]. Previous histological criteria from renal biopsies and portal vein gradient criteria were not included due to practical limitations. On the other hand, in case of patients with kidney transplantation indication and a compensated cirrhosis with clinically significant portal hypertension, a SLK transplant must be performed [23].

Simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation criteria by OPTN 2017.

Abbreviations: eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Recommendation:

- ●

Renal impairment should be thoroughly evaluated in conjunction with a transplantation nephrologist to determine the need for a SLK transplant.

Ultrasonography with doppler and dynamic contrast-enhanced CT or MR must be performed to assess liver morphology and the vascularity, in order to detect abnormalities which may pose technical difficulties or even contraindicate LT, as well to accurately diagnose and stage patients with intrahepatic malignancy in order to confirm transplant candidacy [15,17,18,117]. In patients with renal dysfunction, the timing and modality of contrast-enhanced studies should be carefully considered to minimize nephrotoxic risk [118]. Thanks to the advances in surgical techniques, portal vein thrombosis no longer constitutes a contraindication to LT. Persisting diffuse splanchnic vein thrombosis may preclude LT, except in case that anastomosis of the graft portal vein onto the left recipient renal vein (when spontaneous spleno-renal shunts are present), or on the superior mesenteric vein via a jump graft, if feasible [23,119,120].

Recommendation:

- ●

Recipient anatomical evaluation requires ultrasonography doppler and dynamic contrast-enhanced CT or MR.

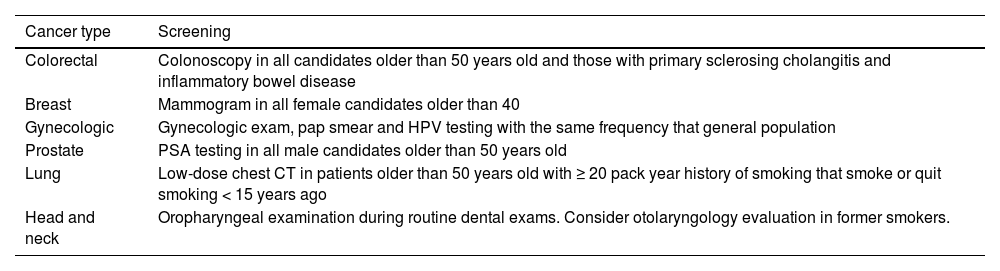

All LT candidates should undergo malignancy screening appropriate to their age, gender, and risk factors [14,15,121] (Table 8). For LT candidates with a history of malignancy, it is crucial that the cancer treatment has been curative and that sufficient time has elapsed to exclude recurrence. The required time interval before transplantation varies based on the type of malignancy [122].

Pre-liver transplant cancer screening recommendations.

Abbreviations: HPV: Human papillomavirus; PSA: Prostate-Specific Antigen; CT: Computed tomography

Recommendations:

- ●

All LT candidates should undergo age, gender, and personal risk-appropriate screening for malignancies.

- ●

In LT candidates with a past history of malignancy, an appropriate time interval to the transplant is mandatory, depending on the type of cancer and the risk of recurrence evaluated by an oncologist.

The goals of pre-transplant infectious disease screening are to identify conditions that would contraindicate transplantation, treat any active infections, assess infection risks, address immunizations, and implement strategies to prevent and manage post-transplant infections (Table 9) [123,124]. Since the advent of antiretrovirals, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) no longer constitutes a contraindication for LT, since LT persons living with HIV had comparable long-term outcomes with those HIV-negative patients [125,126]. Eligibility criteria are: CD4 count over 100 cells/mm³, suppressed or expected suppression of HIV RNA, stable antiretroviral regimen and absence of active opportunistic infection or neoplasm [125,127,128]. Surprisingly, some Latin American centers still consider HIV a contraindication for LT [25] (Supplementary Table 3).

Infectious disease evaluation.

Abbreviations: MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VRE: vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus; CRE: carbapenem‐resistant Enterobactereciae; PPD: Purified protein derivative; IGRA: Interferon gamma release assay; CMV: Cytomegalovirus; EBV: Epstein Barr virus; HAV: hepatitis A virus; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; MMR: measles, mumps, rubella; VZV: varicella zoster virus; HSV: herpes simplex virus; HHV: human herpesvirus; LT: liver transplant; HPV: Human papillomavirus; RSV: Respiratory Syncytial virus.

Recommendations:

- ●

LT candidates should be screened for specific viral, bacterial and parasitic infections.

- ●

Active or uncontrolled infection in the potential recipient should delay transplant until infection resolves or is controlled.

- ●

Vaccination should be encouraged in LT candidates, including hepatitis A and B, pneumococcal, influenza, SARS-COV2 and tetanus.

Key components of the psychosocial evaluation that impact in recipient adherence and consequent in transplant outcomes include assessing social networks, psychiatric illness, and addictions. Psychosocial interventions, coordination of referrals to addiction services, relapse prevention therapy, and practical support from social workers (e.g., housing, transportation) are essential for improving outcomes [129]. In case of HE, neuropsychological testing, CT brain scan or MR and electroencephalography could help to exclude other causes of brain dysfunction if they are suspected [117].

Active drug abuse is generally considered a contraindication for LT. Some Latin American programs exclude patients with active marijuana use [25] (Supplementary Table 3), though this remains controversial. Recent studies have shown no significant difference in post-transplant outcomes, such as mortality, between marijuana users and non-users [124,130,131]. Cigarette smoking is associated with adverse outcomes post-LT, including cardiovascular mortality, hepatic artery thrombosis, and malignancies. Thus, smoking cessation is a prerequisite for listing for LT [14,15]. Active alcohol use has been considered a contraindication to LT. The majority of Latin American centers surveyed require three to six months of abstinence in chronic ALD [25], possibly leading to spontaneous recovery and reducing the risk of alcohol relapse if LT becomes necessary [11,12]. However, this criterion remains controversial since the 6-month mortality in decompensated ALD is extremely high. Therefore, a more centered person approach is recommended, with the application of different scoring systems to assess adequate candidacy [23].

Recommendations:

- ●

Social, psychological, and psychiatric evaluations should be performed to identify potential risk factors for non-adherence after LT and to implement active interventions if such factors are detected.

- ●

Active drug abuse is a contraindication for LT

The current liver allocation system is primarily based on the principle of medical urgency, prioritizing liver candidates at the highest risk of waitlist mortality. The MELD score, developed in 2001, predicts 90-day mortality for candidates on the waitlist [132]. Subsequently, multiple studies demonstrated the impact of hyponatremia in patients with cirrhosis, leading to the incorporation of sodium levels into the model in 2016, creating the MELD-Na [133,134]. Even though MELD-Na remains a useful predictor of waitlist mortality for LT candidates, it has limitations. These include gender disparity in access to LT, the role of creatinine as a surrogate for renal function in cirrhotic patients, among others [135]. To address some of these issues, alternative scores have emerged over the years, such as MELD 3.0 and GEMA-Na [136,137]. While these have been validated in other populations, no published studies in Latin America have yet validated their use. Other factors, including blood type compatibility, distance from the donor hospital, and waiting time, may also impact a candidate's position on the liver offer match run and should be considered. In our region, according to survey data, 3 countries continue to use the MELD score, 9 use MELD-Na [25], and Uruguay recently incorporated MELD 3.0.

Effectively managing waitlisted patients is essential to prevent delisting due to clinical deterioration and to optimize their pre-transplant condition, which has a favorable impact on post-LT outcomes [138].

5.1Patients with elevated MELD scoreWaitlisted patients with MELD scores above 35 face mortality rates exceeding 50 % at 3 months. The key challenge in this cohort is determining the optimal window for transplantation and identifying contraindications in cases of extreme severity [138]. This is particularly important for patients with ALF and ACLF, where the support in the ICU and the rapid identification and treatment of complications is essential.

5.1.1Cerebral edemaA cornerstone in patients with ALF is the management of cerebral edema that induces elevation of intracranial pressure (ICP). ICP should be monitored through non-invasive methods: middle cerebral artery Doppler and measurement of the optic nerve sheath [30], while invasive monitoring should be reserved only in patients at high risk of intracranial hypertension (ICH) due to the risk of hemorrhagic complications [139]. ICH must be treated according to neurocritical guidelines, with the objective of maintaining the ICP < 20 mmHg and cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP = MAP–ICP pressure) >70 mmHg. Monitoring plasma ammonia levels and treatment of hyperammonemia is crucial, since it correlates with HE severity, ICH and cerebral herniation [140]. Insufficient evidence supports the use of lactulose or rifaximin for HE prevention or treatment [33]. The early use of continuous renal replacement therapy to treat hyperammonemia was associated with increased overall and transplant free survival [43,141].

5.2Intermediate and low MELD scoresPatients with intermediate and low MELD scores [18–25] face extended wait times, increasing the risk of acute liver decompensation. To prevent delisting, requesting additional allocation points based on time on the list and decompensation type may be a viable strategy [138]. In Latin America, additional points were awarded for mortality risks not captured by MELD, including refractory ascites, HPS, and overt encephalopathy, as well as HCC and others neoplasia.

Managing conditions such as prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding, ascites and encephalopathy is crucial, alongside regular HCC screening. In cases of refractory ascites, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) may be considered in carefully selected patients by a multidisciplinary team including a hepatologist, surgeon, and radiologist, taking into account local expertise and resources [142]. In case of portal vein thrombosis detected, anticoagulation must be initiated, and in the absence of recanalization after at least 3 months or in the presence of a chronic thrombosis, a TIPS could be considered as a bridge to LT [20]. Anemia management in LT candidates is essential to avoid blood transfusions, which increase risks of alloimmunization and post-LT mortality. Implementing a Patient Blood Management (PBM) protocol optimizes hemoglobin levels and minimizes transfusion-related complications [143].

Treatment of the underlying cause of the liver disease must be contemplated according to the waiting times list and possibilities of function recovery (e.g., hepatitis C, autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson's disease) [138]. For HCC patients, bridging therapies to reduce the risk of drop out due to tumor progression is specially suggested when the expected waiting time is six months or longer. It includes radiofrequency ablation, surgical resection, transarterial chemoembolization, and radioembolization, tailored to HCC type and progression [22,144]. In the survey, HCC progression was a frequent cause of dropout in one-fifth of the centers.

5.2.1Malnutrition, sarcopenia, and frailtyTo mitigate the impact of malnutrition, sarcopenia and frailty on WL mortality, a prehabilitation approach by a multidisciplinary team, that should include a dietician and a physical therapist, must be implemented [23,96,100]. Caloric needs should be assessed through calorimetry or calculated via BMI, with enteral nutrition considered if targets aren't met. Protein intake should be set at 1.2–1.5 g/kg/day. A late evening snack to minimize fasting, and identify and treat factors that contribute to malnutrition such as poor dentition, HE and/or ascites are crucial [96]. Physical activity plans must be tailored to each patient's functional status, focusing on a mix of aerobic and resistance exercises, alongside initial balance and flexibility training for those with significant sarcopenia [100,145].

5.2.2ObesityThe approach to weight loss for obese patients waiting for LT should be stepwise, beginning with lifestyle modifications, emphasis on improving nutritional status and muscle mass by calorie reduction (500–1000 Kcal/day), prioritize protein (1.2–1.5/kg/day) and limit simple carbohydrates, and physical activity. Pharmacologic management of obesity with orlistat, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, and glucagon-like peptide-1 analogs in the perioperative LT period has been proposed, however, little data exist regarding the use of these medications in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Regarding surgical management, although there is no clear consensus on the use of bariatric surgery in the perioperative period, preliminary data suggest that bariatric surgery, when performed before (for those with compensated cirrhosis) or during transplantation (for those with decompensated cirrhosis), can reduce BMI and associated comorbidities, potentially avoiding complications linked with post-transplant surgery [17,23,146].

Recommendations:

- ●

ALF patients should receive intensive care, with close monitoring of ICP and ICH management.

- ●

Supplementary MELD points should be considered for patients when MELD score does not reflect the mortality risk.

- ●

Treatment of the underlying cause of the liver disease should be taken into consideration.

- ●

Patients with HCC must be considered for bridging therapies according to the waiting times list.

- ●

Frailty and obesity should be addressed by a multidisciplinary team through nutritional interventions and physical training.

A percentage of LT candidates will be declined due to contraindications, and others will die on the waiting list. Early palliative care intervention can significantly improve quality of life by alleviating symptoms and enhancing mood, while reducing aggressive treatments and hospitalizations [16,147]. However, palliative care services are often underutilized [148] and delayed [149]. Assessment of palliative care needs as part of the evaluation and waiting list management processes represents an important area for improvement.

7ConclusionsLatin America has made significant progress in LT despite the socio-economic barriers faced by many countries in the region. Over the past decades, the number of LT performed has increased steadily, and survival rates are comparable to those in developed countries, reflecting the quality of care and expertise that has been cultivated across the continent. LT has proven to be a transformative treatment, offering long-term survival and improved quality of life for patients with end-stage liver disease. To sustain this progress, efforts should focus on enhancing access to LT, refining clinical protocols, and investing in healthcare infrastructure. Collaborative support is crucial for countries without LT programs to develop and implement these services. By addressing barriers and fostering regional collaboration, Latin America is well-positioned to continue advancing LT and improving outcomes for all patients.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT in order to improve grammar, check spelling and enhance language clarity. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributionsConceptualization: Victoria Mainardi, Josefina Pages, Josemaria Menendez, Rodrigo Zapata, Alejandra Villamil, and Solange Gerona. Web-based Survey Creation: Victoria Mainardi, Josefina Pages, Josemaria Menendez, Alejandra Villamil, and Rodrigo Zapata.

Web-based Survey Participants: Victoria Mainardi, Josemaria Menendez, Josefina Pages, Alejandra Villamil, Rodrigo Zapata, Manuel Mendizabal, Sergio Lopez, Adriana Varon, Alfeu de Medeiros Fleck Jr., Jhon Abad Gonzalez, Juan Carlos Restrepo, Liana Codes, Paulo Lisboa Bittencourt, Norma Marlene Pérez Figueroa, Graciela Castro-Narro, Débora Raquel B. Terrabuio, Mário Guimarães Pessoa, Marcos Girala, Leonardo Lucca Schiavon, Edgard Aguilera, Kenia Valenzuela Aguilera, and Marcia Samada. Chapter Writing: Victoria Mainardi, Josefina Pages, Josemaria Menendez, Alejandra Villamil, Rodrigo Zapata, Luis Antonio Díaz, Sebastian Marciano, Fernando Cairo, Martin Padilla-Machaca, Laura Tenorio, Alvaro Urzua, Lucia Navarro, Nicolas Dominguez, Jorge Martinez, and Pablo Coste. Original Draft Preparation: Victoria Mainardi, and Josefina Pages. Reviewing: All authors. Editing: Victoria Mainardi, Josefina Pages, Josemaria Menendez, Rodrigo Zapata, Luis Antonio Díaz, Sebastian Marciano, Manuel Mendizabal, Solange Gerona, and Alejandra Villamil. Supervision: Victoria Mainardi, Josefina Pages, and Alejandra Villamil.

Editorial noteThe journal acknowledges the valuable contributions of the peer reviewers involved in the evaluation of this manuscript. With consent, we thank Dr. Giulia Pagano, PhD, for his review.

None.