The liver is the second-largest organ in the human body. In adults, it constitutes approximately 2 % of total body weight [1]. The liver is fundamental for diverse physiological processes, such as protein and amino acid metabolism, detoxification, the metabolism of drugs and xenobiotics, the storage of glucose in the form of glycogen, and the elimination of endogenous and exogenous compounds [2–3]. The liver has an important and interesting regenerative capacity, allowing it to recover its normal mass and function in response to any type of acute or chronic damage [4,5]. Liver diseases are a major global health challenge affecting millions of people [6,7]. After injury, the liver usually recovers its original function, architecture, and histological organization through the proliferation and remodeling of its viable cells, whereas chronic injury caused by multiple insults, including pathogens, alcohol abuse, and metabolic disorders, results in the production of fibrotic tissue characterized by excessive production of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and inflammation, compromising the structural integrity of the organ and leading to severe liver damage conditions such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer (HCC) [8,9].

Conditions such as hepatitis, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), fibrosis, cirrhosis, and even HCC can lead to liver failure [9,10]. The pathological complexity of these diseases results in diverse molecular responses, which are mediated by various signaling pathways that are activated to regulate the progression of the lesion and reverse damage [11]; however, on many occasions, this response is aberrantly activated, leading to further damage, such as in the case of the Hh pathway, which is our object of study [9,10].

The Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway was first described regarding the embryonic development of Drosophila melanogaster [12,13]. This signaling is crucial for embryonic development, as it regulates several critical cell fate decisions, including proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, and migration [14], and its inhibition leads to craniofacial malformations [15,16]. In adults, it participates in tissue homeostasis through its effects on hepatic progenitor cells (HPCs), wound healing, and organ regeneration [17,18]. Furthermore, its aberrant activation in adults is related to the pathogenesis of several diseases, such as MASLD, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and the progression of distinct types of cancer, including HCC [19–22]. Additionally, some reports of Hh activity in the presence of hepatitis viruses exist [23–25].

Three Hh homologs have been identified in mammals: Sonic hedgehog (Shh), Desert hedgehog (Dhh), and Indian hedgehog (Ihh). These ligands initiate the activation of this pathway by binding to its main receptor, Patched (Ptc). This binding activates the coreceptor known as Smoothened (Smo), resulting in intracellular signal propagation, terminating the nuclear translocation of the transcription factor Glioma (Gli), an important regulator of target genes [26,27]. In the absence of a ligand, the coreceptor is inhibited, preventing its translocation to the primary cilium and preventing downstream activation of the Hh pathway [28,29]. In the presence of Hh ligands, the coreceptor is released from the intracellular vesicles into the primary cilium, causing downstream activation of the Hh pathway; the transcription factor subsequently translocates to the nucleus, leading to the transcription of target genes involved in various cellular processes controlled by this mechanism [30,31].

In healthy adult livers, Hh pathway activity is low due to low ligand expression and high expression of negative pathway regulators. However, in patients with various types of acute and chronic liver injury, the Hh pathway is differentially and dramatically reactivated. In patients with liver fibrosis resulting from chronic liver damage and ECM accumulation, hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) are known to respond to activation of the Hh pathway, leading to their activation and consequently to increased ECM production [32,33].

Additionally, in patients with mechanical damage caused by partial hepatectomy (pH), activation of the Hh pathway significantly favors the liver regeneration process. This was demonstrated by inhibiting this pathway with cyclopamine in hepatectomized mice, which showed deficient liver regeneration compared with that in nontreated animals [4]. Moreover, the damage caused by a parasite such as Entamoeba histolytica decreases when an inhibitor of this signaling pathway is administered, contributing to the process of organ regeneration [34]. Although the liver has important regenerative capacity, defective regenerative responses can occur, replacing the liver parenchyma with scar tissue and leading to fibrosis and cirrhosis that can progress to HCC. In this context, the Hh pathway may play a pivotal role in the liver repair process, suggesting that the Hh pathway is a putative therapeutic target for the treatment of liver diseases [27].

Regarding cancer development, dysregulation of the Hh pathway has been suggested to play a key role in cell proliferation and differentiation, leading to tumorigenesis in a wide variety of tissues [35,36]. The Hh pathway is aberrantly activated by ligand overexpression, loss of receptor function, or transcription factor dysregulation [37]. This abnormal activation is implicated in various tumor behaviors, such as progression, drug resistance, and metastasis [38,39]. The first evidence of Hh-dependent tumors was described in patients with Gorlin syndrome caused by a mutation in the receptor gene, which is the main gene involved in cancer development [17,40].

Owing to the clinical implications related to the aberrant activation of the Hh pathway, a search for inhibitors of natural and synthetic origin that can be used as therapeutic alternatives has been conducted. Smo, a central Hh regulator, has been the main target for inhibitor development [41]. Among the most studied inhibitors of the Hh pathway related to various biological processes is cyclopamine, a natural alkaloid present in the plant Veratrum californicum; this alkaloid was first described as an inhibitor of the Hh pathway due to the presence of craniofacial deformities in newborn sheep, and its inhibitory effect is due to the binding of cyclopamine to Smo [42]. Other inhibitors that have been described are vismodegib, sonidegib, glasdegib, patidegib, and itraconazole, which are currently used clinically as alternative treatments for several types of cancer [37,43].

The objective of this review is to present the general aspects of the Hh pathway and the scientific reports available to date on its participation in several liver diseases.

2Hh signaling pathway overviewThe Hh signaling pathway has diverse biological effects and important functions related to embryonic development. Similarly, in adults, it is involved in wound healing, regeneration, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and the development of different types of cancer. The Hh pathway is a cascade that comprises several components, including ligands, receptors, and a transcription factor, which are responsible for Hh activation (Table 1).

Constituent molecules of Hh, and main characteristics.

The Hh ligands are localized in different organs such as the central nervous system, lungs, liver, ovarian and testis cells, and bones [26].

The receptor Ptc, comprising twelve transmembrane domains, has a transmembrane structural domain composed of a sterol-sensing domain and two extracellular domains [44]. Humans have two Ptc proteins (Ptc1 and Ptc2). Ptc1, which is the principal receptor of the Hh pathway, significantly inhibits the coreceptor Smo, and is expressed mainly in mesenchymal cells. While the expression of Ptc2 is different from that of Ptc1 and has a lower ability to inhibit Smo in the absence of a ligand, analysis of its distribution across tissues indicates that it is differentially expressed in the skin and testis, conferring diverse functions [26,45]. However, further studies of Ptc2 are needed to elucidate its involvement in this pathway. Smo has seven transmembrane domains, similar in structure to G protein-coupled receptors, and an extracellular cysteine-rich domain essential for its proper function [46].

The transcription factor Gli acts as a transcriptional activator of target genes by directly binding to their promoters through its zinc finger structural domains [27,45]. In vertebrates, there are three members of this transcription factor family (Gli1, Gli2, and Gli3). Gli1 is the exclusive transcriptional activator of the Hh pathway, whereas Gli2 and Gli3 can act as activators and repressors. These proteins can be phosphorylated and proteolytically processed, preventing Gli1 from translocating to the nucleus in its full form and inhibiting the transcription of target genes [47,48].

On the other hand, in the liver, the nonparenchymal cells, including HSCs, natural killer T cells, and cholangiocytes, are known to produce Hh ligands in the setting of liver injury. The Hh-responsive cells in the liver include progenitor cells, HSCs, and biliary epithelial cells, whereas normal adult hepatocytes are nonresponsive to Hh ligands [49]. Hepatocytes are generally considered to lack primary cilia, which are canonical structures required for Hh signaling. Nevertheless, several studies indicate that Hh signaling in hepatocytes may occur through non-canonical mechanisms [50]. In this context, activation does not rely on the primary cilium but rather involves direct modulation of intracellular signaling cascades, which can regulate cell survival, metabolism, and stress responses [51,52]. In addition, hepatocytes may also respond indirectly to the paracrine Hh pathway produced by neighboring nonparenchymal cells, which do possess primary cilia. These cells release soluble mediators downstream of Hh activation that can, in turn, modulate hepatocyte proliferation, survival, and metabolic adaptation [14,49]

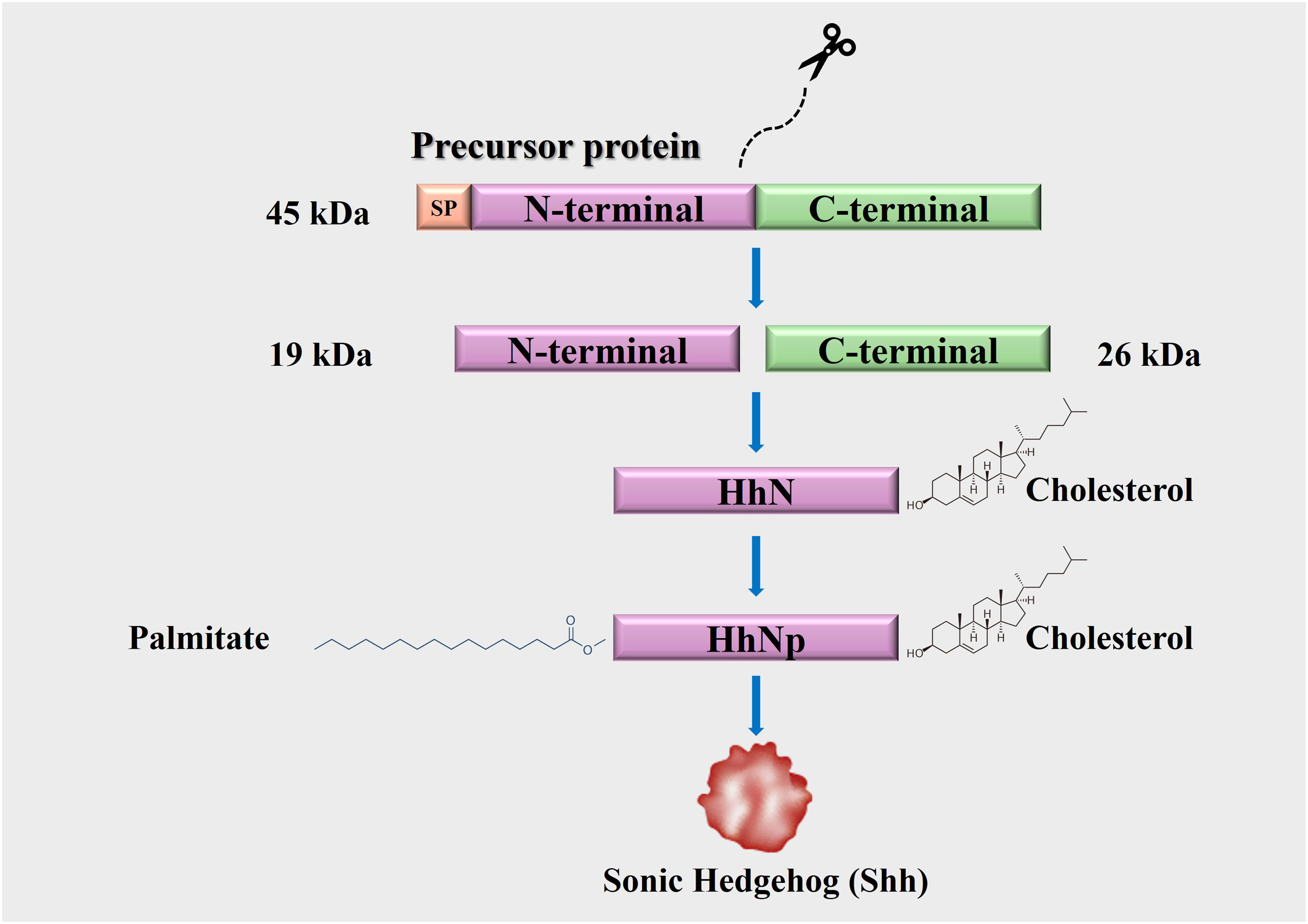

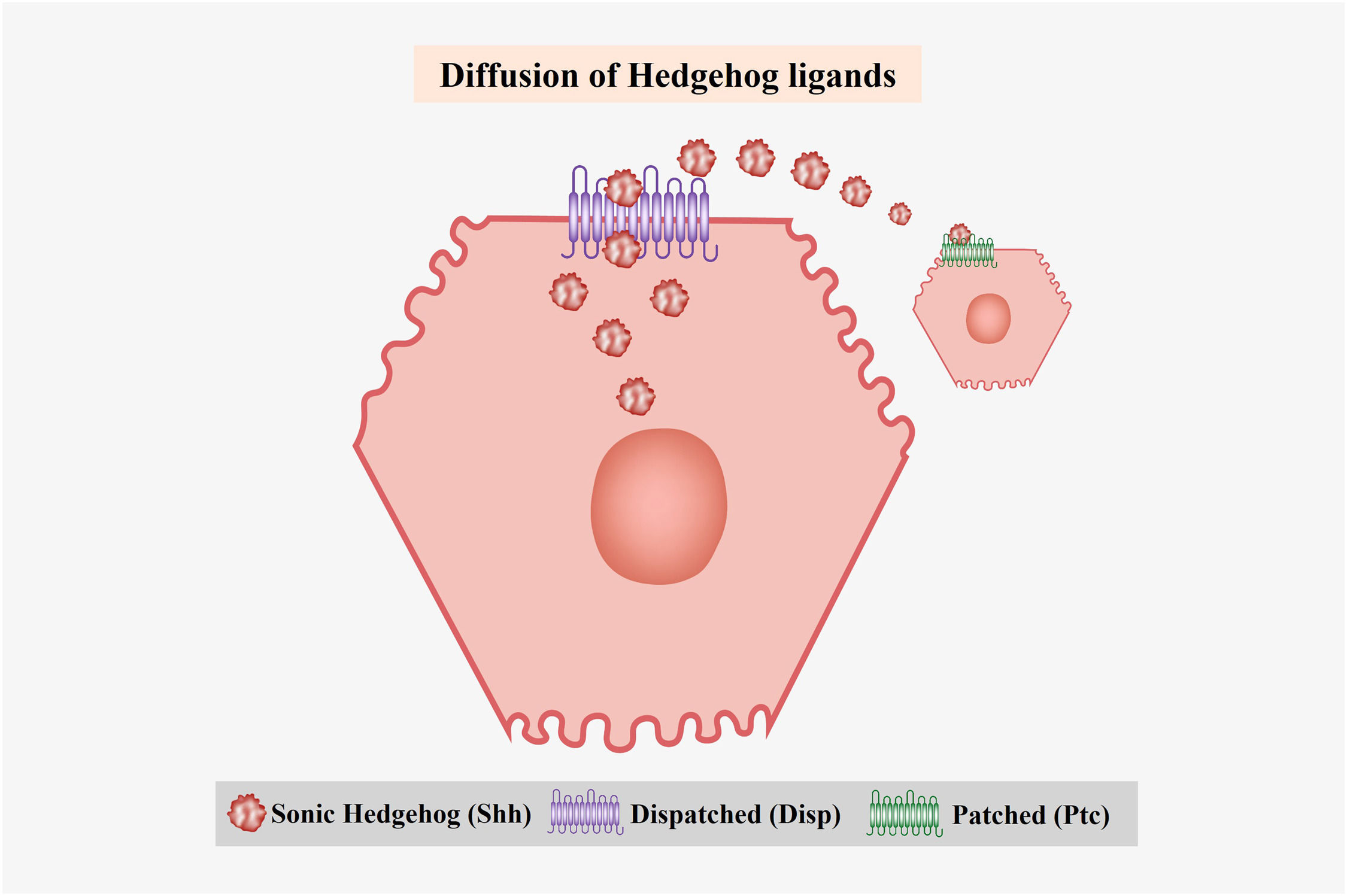

3Hh protein synthesis and processingHh ligands are synthesized as 45 kDa precursor proteins that undergo autocatalytic cleavage and posttranslational modifications. They consist of an endoplasmic reticulum-targeting signal peptide (SP), an N-terminal domain, and a C-terminal self-processing domain with autoproteolytic activity and cholesterol transferase, which undergo a process of intramolecular hydrolysis catalyzed by their C-terminal portion, forming two peptide fragments (N-terminal and C-terminal) [26,27]. The 26 kDa C-terminal peptide lacks biological activity, whereas the 19 kDa N-terminal fragment (HhN) possesses biological activity [53]. Subsequently, a cholesterol molecule covalently binds to the C-terminus of HhN, generating a processed fragment (HhNp) to finally acquire a palmitic acid molecule at its N-terminus through covalent binding, facilitating the secretion of Hh proteins into the extracellular space [53] (Fig. 1). This secretion is carried out by Dispatched (Disp), a protein with twelve transmembrane domains and a sterol-sensing domain responsible for interacting with the Hh ligands, allowing for their liberation [14,26] (Fig. 2).

Hedgehog (Hh) protein synthesis and processing. The Hh ligands are synthesized as 45 kDa precursor proteins. Their C-terminal domains have autoproteolytic activity. This generates two fragments (N-terminus and C-terminus). Only the N-terminal fragment has biological activity and undergoes posttranslational modifications (cholesterol and palmitate) that facilitate its secretion to the extracellular medium.

Diffusion of Hedgehog (Hh) ligands. The Hh ligands are diffused to the extracellular medium through Dispatched (Disp), a protein with twelve transmembrane domains. Once the ligands are released, they are recognized by their main receptor Ptc, which causes the activation of the signaling pathway.

The proteins related to the Hh pathway accumulate in the primary cilium, an organelle present in all cell types, whose central structure is an axoneme projected toward the cell surface. Its membrane forms a continuous structure with the plasma membrane and possesses many receptors and ion channels [54]. This signaling pathway can canonically be activated by binding the Hh ligand to its receptor, and it can also be activated in a noncanonical manner.

Noncanonical signaling is classified into Ptc-dependent and Smo-dependent but independent of Gli [55]. The noncanonical activation of the Ptc-dependent pathway is related to apoptosis and cell cycle regulation through the interaction of this receptor with cyclin B1 and caspase-3; this response is blocked once Hh ligands are present. Smo-dependent, noncanonical activation is involved in actin cytoskeleton rearrangement, metabolic reprogramming, and calcium release; Smo can interact with several molecules involved in these processes since it belongs to the GPCR superfamily [47,55].

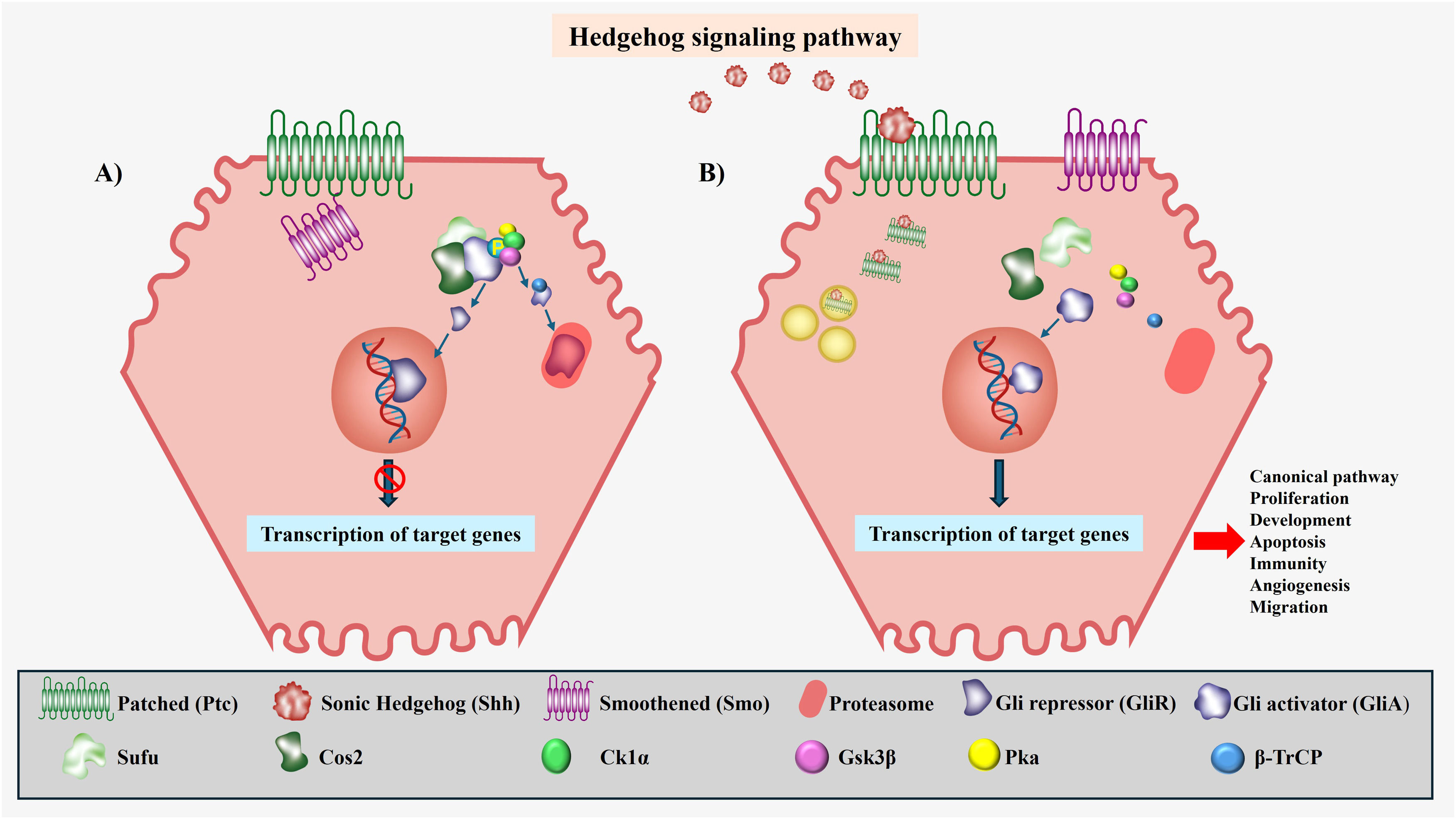

The canonical Hh pathway involves two transmembrane proteins in the receptor cell, Ptc and Smo. In the absence of a ligand, the Ptc receptor is localized to the base of the primary cilia, where it negatively modulates Smo activity [20,28]. Under these conditions, Gli is retained in the cytoplasm by the signaling microtubule-binding complex that includes suppressor of fusion and Costal 2; this complex promotes the phosphorylation of the complete form of Gli by three serine‒threonine kinase proteins (protein kinase, glycogen synthase kinase-3β, and casein kinase-1α), giving rise to two fragments: a Gli fragment with repressor activity (GliR) corresponding to its N-terminus, which translocates to the nucleus, suppressing the transcription of target genes; and a fragment corresponding to its C-terminus, which is recognized by E3 ubiquitin ligase β-transducin repeat-containing protein for subsequent proteasomal degradation [27,56] (Fig. 3A).

The Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway. A) Pathway Off. When the signaling pathway is inactive, there is no production of Hh ligands; therefore, Ptc can inhibit Smo. This negative modulation of Smo translates to the retention of Gli in the cytoplasm by the complex formed by SuFu and Cos2, promoting the phosphorylation of Gli by Ck1α, Gsk3β, and Pka, generating two fragments, one corresponding to the N-terminal end known as the repressor fragment (GliR) of the target genes and another fragment corresponding to the C-terminal end that β-TrCp recognizes for its subsequent degradation in the proteosome. B) Pathway On. When the signaling pathway is active, there is production of Hh ligands, the ligands binding with Ptc, causing the internalization of ligand‒receptor complex for degradation in the lysosome. Once ligand‒receptor binding has occurred, Smo is released to the primary cilium, where it activates the pathway, preventing the phosphorylation of Gli to enable translocation to the nucleus in its complete form or in a form known as activating fragment (GliA), to give way to the subsequent transcription of target genes.

In the presence of a ligand, the first step in the signaling process is the binding of Hh to Ptc, causing activation of the pathway and, simultaneously, internalization of the Hh-Ptc complex by endocytosis and its subsequent lysosomal degradation [20]. Once the Hh-Ptc complex is formed, Smo is released through intracellular vesicles that move to the primary cilium, resulting in the inhibition of Gli phosphorylation and proteolysis, allowing its translocation to the nucleus in its complete and activating form (GliA), thereby inducing the transcriptional activation of target genes [26] (Fig. 3B). As a result of the complex transcriptional behavior of Hh, the activation of target genes can vary depending on the tissue or cell type in which pathway activity takes place. These target genes include pathway-specific molecules such as Ptc and Gli, which are involved in development, apoptosis, proliferation, immunity, angiogenesis, and migration [26,30,44].

5Hh signaling in liver development and homeostasisDuring liver development, proteins related to the Hh pathway are expressed in the endoderm of the ventral intestine, from which the liver and other organs originate. The expression disappears once the liver bud is formed. The role of this pathway in liver development was investigated in a mouse embryo model. The Hh pathway is reportedly active in the early stages of development and decreases as this organ forms. The isolation of hepatoblasts reveals that Hh is expressed in these cells, as confirmed by RT‒PCR, suggesting that activation of the pathway during liver development targets hepatoblasts. This pathway stimulates the proliferation of Shh ligand-producing hepatoblasts; once these cells differentiate into hepatocytes, Hh expression decreases dramatically [57].

In HPCs, Hh activation enhances proliferation, ensuring a sufficient pool of bipotential hepatoblasts capable of differentiating into hepatocytes or cholangiocytes. Hh is also considered to be expressed in this cell type during embryogenesis and is conserved until the adult stage, where it is activated to reverse or aggravate the response to injury [10,58]. Furthermore, the Hh pathway has been shown to participate in yolk sac angiogenesis, which has been demonstrated in Smo-deficient embryos that do not form blood vessels [59] and has been proposed to regulate vascular endothelial growth factor expression in mouse embryos [60].

In the adult liver, the Hh pathway is typically suppressed but can be reactivated in response to injury, metabolic stress, or inflammation. This pathway influences HSCs, cholangiocytes, HPCs, and immune responses, playing a key role in tissue repair, metabolic adaptation, and liver regeneration. Quiescent HSCs store vitamin A, but upon liver injury, they become activated and produce ECM components [61]. Hh signaling drives HSC activation, contributing to liver regeneration; however, chronic activation promotes fibrosis [62]. Additionally, Hh regulates cholangiocyte proliferation and bile secretion, thereby playing a role in cholestatic diseases and biliary fibrosis [63]. In HPCs, Hh signaling supports tissue repair by stimulating cell proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis [64]. Recent studies have also suggested that Hh influences lipid metabolism and glucose regulation, contributing to MASLD and insulin resistance when dysregulated, and that it plays an important role as a proangiogenic agent in patients with pathological conditions [65].

6Implications of the Hh pathway in liver diseasesOver the years, liver disease has become one of the leading causes of death worldwide [7]. Faced with diverse chemical, mechanical, and pathological affronts that cause cellular damage, the liver generates a persistent regenerative response that promotes molecular signals responsible for the recovery of the hepatic parenchyma [14,27,53]. However, chronic progressive liver injury induces repetitive tissue damage, resulting in a defective regenerative response, as evidenced by the presence of an inflammatory process and defective remodeling of the ECM, which can eventually lead to fibrosis and cirrhosis that can progress to HCC [14,27].

Recent studies have highlighted the pivotal role of the Hh pathway in these processes, as it is involved in the regulation of liver repair, fibrosis progression, and carcinogenesis. Activation of the Hh pathway has been shown to modulate HSC behavior, promoting transdifferentiation into myofibroblasts, which contributes to excessive ECM deposition and fibrogenesis [33].

Additionally, the Hh pathway interacts with key inflammatory mediators, influencing immune cell recruitment and perpetuating chronic liver inflammation. In MASLD and MASH, the Hh pathway plays crucial roles in hepatocyte injury, lipid metabolism dysregulation, and fibrosis development. Furthermore, evidence has suggested that aberrant activation of the Hh pathway in cirrhotic livers creates a microenvironment that favors HCC initiation and progression by enhancing angiogenesis, epithelial‒mesenchymal transition (EMT), and cancer stem cell expansion [48]. Understanding the precise mechanisms underlying these interactions may provide novel therapeutic opportunities for liver disease management.

6.1The role of the Hh pathway in liver regenerationLiver regeneration is a highly specialized process governed by a tightly regulated molecular network involving cytokines, growth factors, and signaling pathways responsible for liver tissue repair [66]. Under normal conditions, the architecture and mass of the liver are restored through compensatory hyperplasia and hypertrophy after pH; however, under pathological conditions, these molecular mechanisms can become dysregulated, leading to impaired regeneration [67,68]. To better understand this process, several experimental models have been developed. Liver injury can be induced by chemical or mechanical means, with pH being the most studied rodent model. In this procedure, two-thirds of the liver is removed, triggering a compensatory response in which the remaining lobes enlarge to restore the original organ mass through a series of molecular signals [69,70].

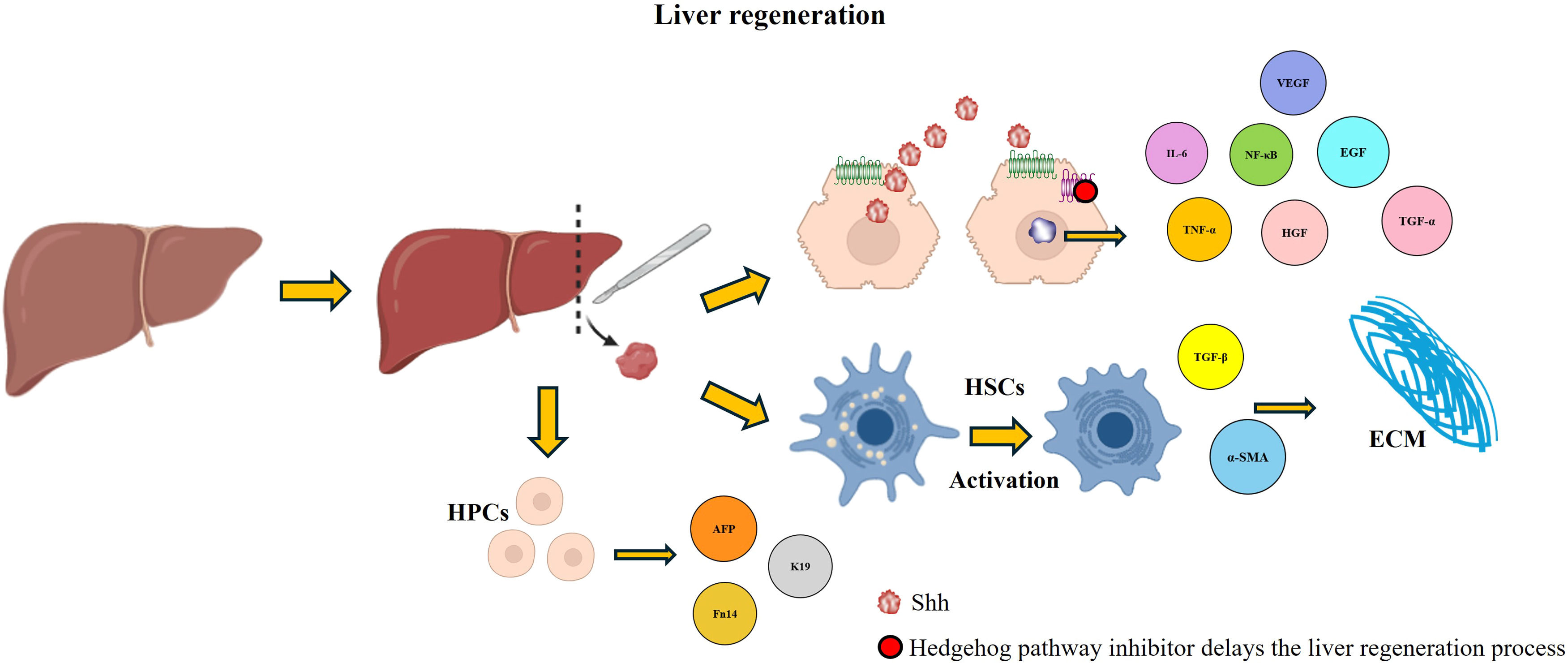

Recent research has underscored the pivotal involvement of the Hh pathway in liver regeneration (Fig. 4). Under chronic liver injury conditions, the production of Shh ligands is upregulated, driving the expansion of HPCs, recruitment of inflammatory cells, fibrogenesis, and vascular remodeling [14,18,21]. During hepatic damage, injured hepatocytes, HSCs, and immune cells secrete the ligand Shh, which subsequently induces chemokine expression in biliary epithelial cells [71]. Once activated, the Hh pathway can stimulate a variety of cell types to produce chemokines and other chemoattractants, further amplifying regenerative and fibrotic responses [72].

Hedgehog (Hh) activation in liver regeneration. The activation of the Hh pathway favors the process of liver regeneration; different molecules that play crucial roles in this process are expressed, which are affected when an inhibitor of the pathway is administered, delaying liver regeneration.

While some studies have suggested that liver regeneration depends only on hepatocyte replication, recent research has indicated that HPCs also play a significant role, particularly after pH [73]. HPCs are bipotential cells capable of differentiating into hepatocytes or cholangiocytes. Studies have shown that Hh signaling increases HPC proliferation, as demonstrated by increased expression of markers such as AFP, K19, and Fn14, which ensures an adequate cellular reserve for regeneration after injury [14,21]. Notably, inhibiting the Hh pathway after pH in mice drastically reduces HPCs accumulation, suppresses hepatocyte and cholangiocyte proliferation, disrupts ECM remodeling, inhibits cell proliferation by affecting cyclin D and Cdk2 expression, and alters the cell cycle by inducing cyclin B accumulation, which indicates the failure of cells to successfully complete mitosis and exit the cell cycle [4,74]. These alterations eventually delay liver regeneration, leading to fatal outcomes. Another study showed that Smo blockade inhibits hepatic fibrosis and the accumulation of HSCs and prevents the accumulation of HPCs [32].

Additionally, chorionic plate-derived mesenchymal stem cells (CP-MSCs) are known to be involved in the regeneration process. In model rats treated with a hepatotoxicant (carbon tetrachloride), increased production of Hh ligands (Shh and Ihh) was observed in intoxicated animals. In a group of animals that received a CP-MSC transplant in addition to the hepatotoxicant, the production of Hh ligands was lower [75]. These findings suggest that these cells regulate the expression of Hh ligands, decreasing the probability of damage progressing to a fibrotic process and favoring the process of hepatic regeneration [75].

Similarly, the role of the Hh pathway in a model of hepatic regeneration in experimental amebiasis has been described [34]. Metronidazole was administered to hamsters previously inoculated with virulent E. histolytica, which produced amebic liver abscesses. In addition, cyclopamine, an inhibitor of the Hh signaling pathway, was administered. The Hh pathway was shown to be active during damage, which had not previously been shown [34]. It has also been reported that the administration of signaling pathway inhibitors results in organ alterations including a significant increase in lesion size, increased inflammatory responses and ECM production, and a significant decrease in Shh expression. The reported results demonstrate that the Hh pathway plays a key role in the process of liver regeneration following pathogenic damage [34].

6.2The Hh pathway in the progression of MASLDMASLD is a metabolic disorder associated with lipid accumulation in the liver. This disease can cause different types of liver damage that, over time, could lead to serious problems such as cirrhosis or even HCC [76]. Genetic, epigenetic, dietary, and environmental factors play essential roles in their progression [77]. At present, it is considered the most common chronic liver disease [77]. It can be improved by modifying one’s eating habits and exercising. This condition can progress to MASH when the liver can no longer metabolize free fatty acids, thus generating highly damaging lipid species and consequently activating lipotoxic pathways that worsen the injury to a chronic state of hepatic inflammation that subsequently triggers the activation of HSCs, exacerbating the production of ECM and eventually leading to the development of liver fibrosis [9,78].

MASH involves the ballooning and inflammation of hepatocytes. Patients with MASH have significant alterations in inflammatory and immune signaling pathways, increased ROS production, and endoplasmic reticulum stress [79]. At present, there is no specific treatment to reverse this disease; however, multiple studies have been conducted that target various molecules that play a role in the development of the disease [79,80].

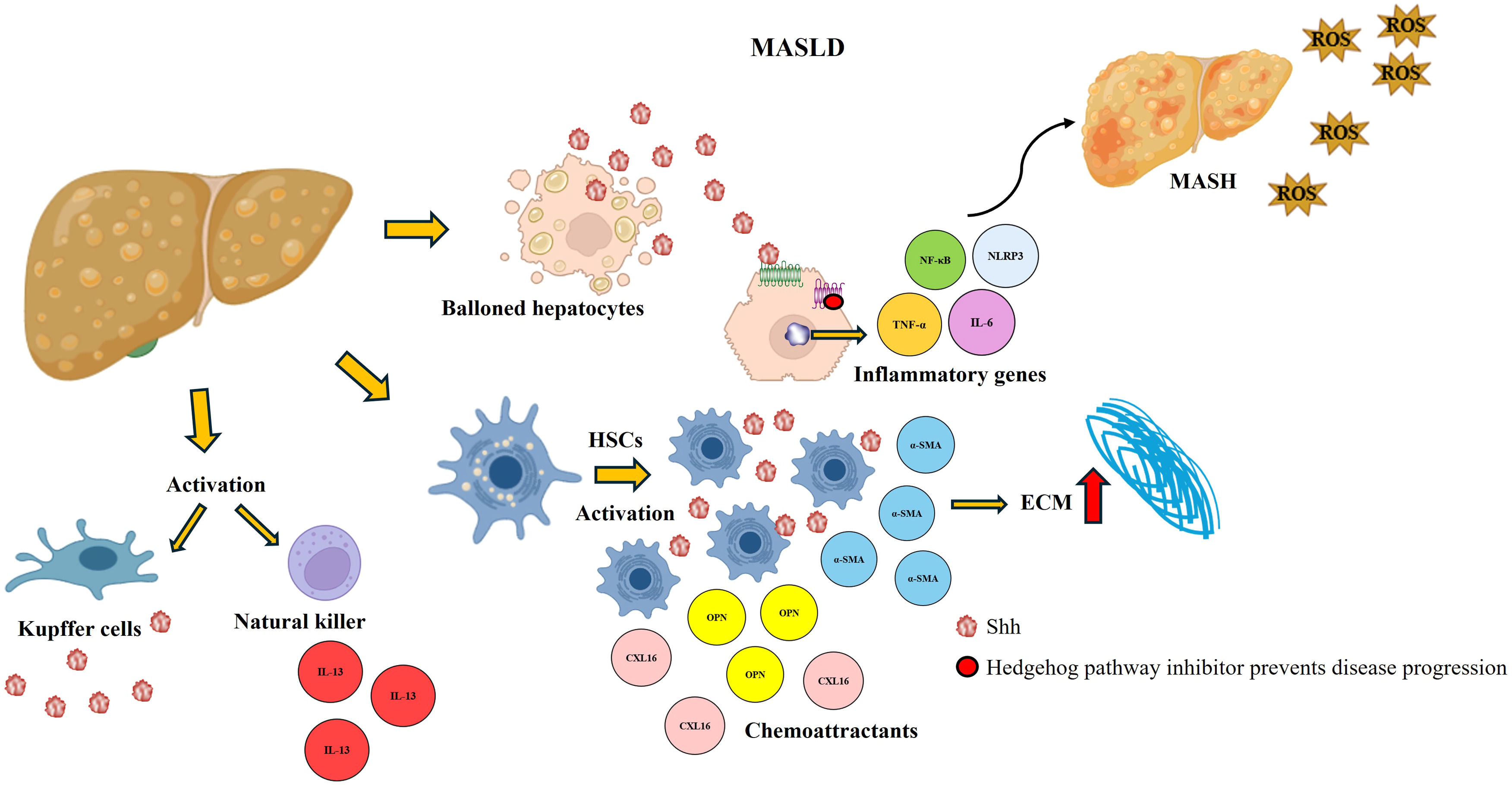

Under normal conditions, the expression of Hh ligands in the liver is detectable at very low levels. However, the Hh pathway is activated and expressed proportionally to the intensity and duration of a hepatic insult [18] (Fig. 5). In MASLD, lipid accumulation in hepatocytes induces cellular stress and triggers the release of Hh ligands [21,81]. These ligands interact with neighboring liver cells, including Kupffer cells, HSCs, and endothelial cells, leading to a cascade of events that exacerbate liver damage [12,82]. Ballooned hepatocytes are known to be crucial indicators of MASH. In a study performed using samples from patients with MASH, an increase in the production of Shh ligands was observed; these ligands activate natural killer cells, which secrete Hh ligands and profibrogenic cytokines such as interleukin-13, that promote disease progression. Interestingly, ballooned hepatocytes are surrounded by Gli-expressing stromal cells [83,84].

Hedgehog (Hh) activation in MASLD. The Hh pathway is overactivated in patients with the metabolic disorder, which causes the activation of ECM-producing HSCs and is accompanied by the expression of molecules that favor the damage and allow its progression to more severe forms, such as MASH. The Shh ligand interacts with Kupffer cells and activates natural killer cells, promoting increased damage. When an Hh inhibitor is administered, there is a decrease in the expression of these molecules, damage is reduced, and progression to more severe forms is prevented.

In animal models, activation of the Hh pathway has been shown to induce expression of genes by HSCs, leading to fibrosis; activation of HSCs is responsible for the secretion of Hh ligands and the release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemoattractants such as osteopontin and the chemokine ligand with CXC motif 16. Notably, these effects are significantly attenuated by an Hh pathway inhibitor [27]. Hh pathway activity is correlated with the degree of portal inflammation, whereas the stage of fibrosis is correlated with the number of Gli-expressing cells [82,85]. In addition, activation of the Hh pathway is involved in metabolic dysregulation, as it regulates lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity, thereby worsening hepatic lipid deposition [86,87].

6.3The Hh pathway in liver fibrosisLiver fibrosis is a major contributor to mortality, as it disrupts both the architecture and function of the liver and, indirectly, other organs. Under physiological conditions, fibrosis serves as a reparative mechanism aimed at preserving injured tissue. However, when this process becomes chronically activated, irreversible structural changes that drive the progression toward end-stage liver disease occur [78]. Fibrosis may result from a variety of chronic liver conditions, including obesity, viral hepatitis, excessive alcohol intake, fat accumulation, or autoimmune disorders [88]. During fibrogenesis, the hepatic parenchyma undergoes extensive remodeling marked by excessive deposition of ECM by HSCs activated by transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling, along with impaired ECM degradation [8,89]. Prolonged activation of this process culminates in cirrhosis, a condition characterized by profound alterations in liver architecture. This includes hepatocyte necrosis, degeneration, the replacement of functional tissue with fibrotic scarring, the formation of regenerative nodules, angiogenesis, and the progressive loss of liver function—ultimately increasing the risk of liver failure and death [90].

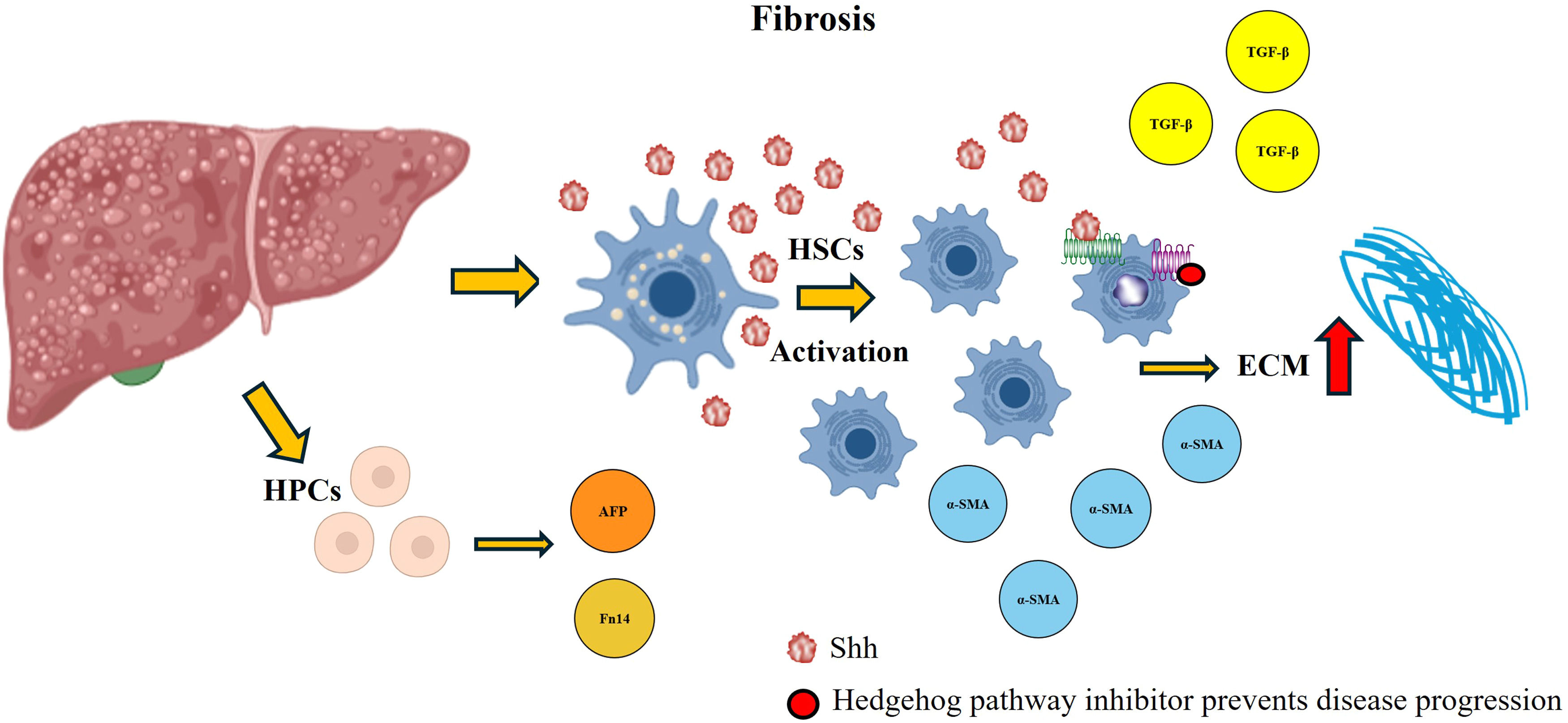

Several signaling pathways are involved in the modulation of appropriate molecular responses to tissue damage. However, aberrant activation of these pathways can induce dysregulation of these processes, promoting pathological mechanisms that amplify damage [11], as has been observed in the Hh pathway (Fig. 6).

Hedgehog (Hh) activation in fibrosis. During the development of fibrosis, the Hh pathway is overexpressed, which favors the activation of HSCs and an increase in ECM production. In addition, this pathway favors the production of profibrogenic cytokines that participate in the damage process and allow the accumulation of HPCs. By administering a signaling pathway inhibitor, the abundance of these molecules decreases, the damage decreases, and the progression to more severe forms is stopped.

As mentioned above, HSCs play a key role in the development of fibrosis. These cells express Shh ligands and respond to this signaling pathway to initiate ECM production and the regulation of angiogenesis. Once activated by Hh ligands, HSCs can induce the synthesis of matrix molecules, metalloproteinases, and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases, which favor ECM accumulation [33]. During fibrogenesis, various cytokines and growth factors induce Shh ligand secretion by HSCs, which enhances ECM accumulation [33]. Once activated, these cells accumulate in the lesion site, promoting the overexpression of genes involved in fibrosis [8]. Moreover, the production of Hh ligands not only favors the proliferation and survival of HSCs but also stimulates the accumulation of HPCs [32]. These cells play an essential role in liver regeneration when hepatocytic autonomous replication mechanisms are compromised, contributing to tissue repair through their proliferation and differentiation [57,91]. Recent studies have shown that the administration of Hh pathway inhibitors effectively attenuates fibrosis and the activation of HSCs and HPCs [92,93].

6.4The Hh pathway in viral infectionsViruses are considered obligatory intracellular parasites since they require a cell to replicate. These microorganisms can infect several organisms, from bacteria to humans [94]. The liver is a key organ for blood filtration, making it particularly susceptible to blood-borne viruses that can lead to hepatic infections [36,95]. These viral infections can directly affect the liver, causing inflammation and liver damage with a risk of progressing to chronic diseases such as cirrhosis or HCC [96].

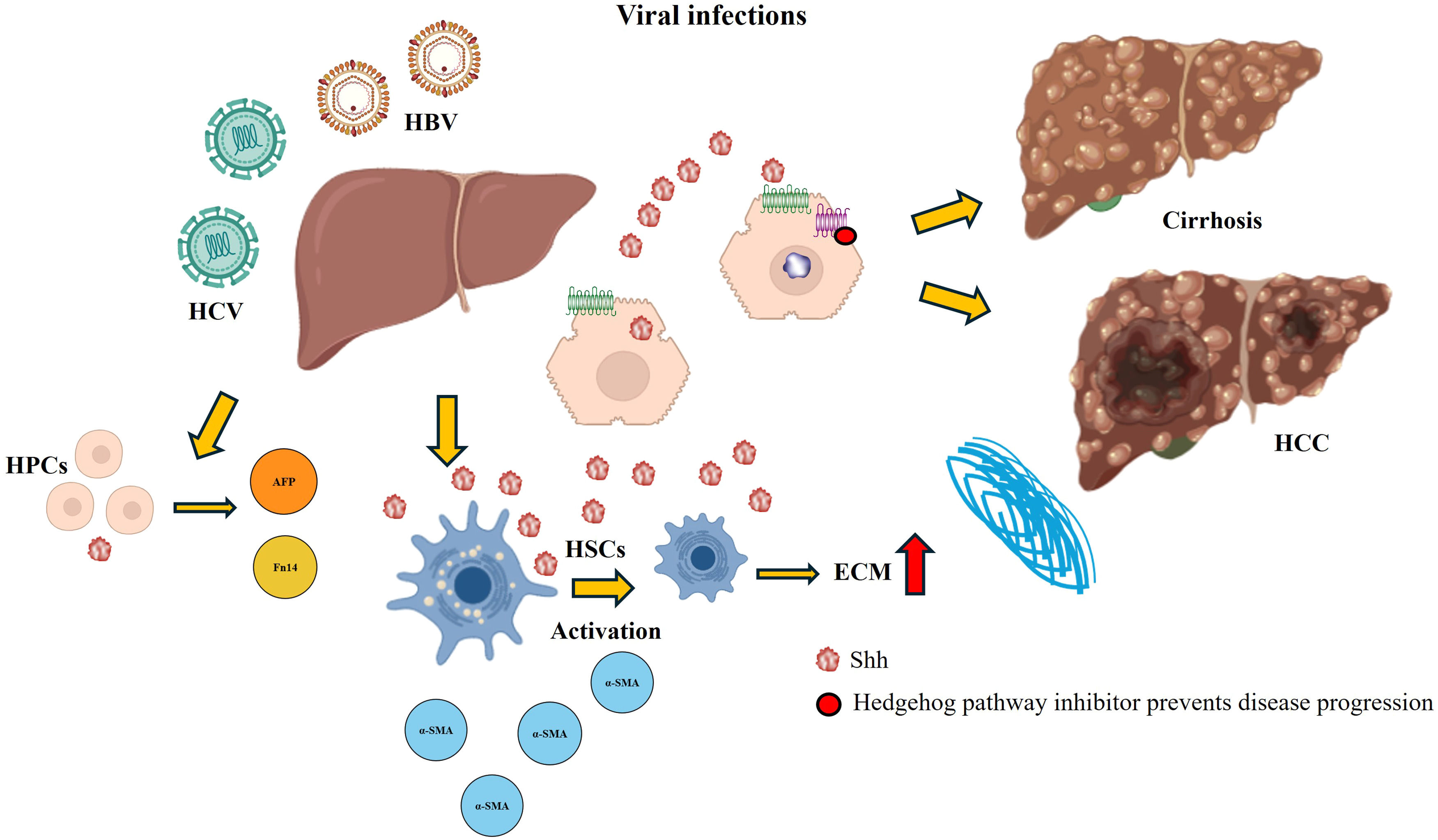

It is now known that the Hh pathway is a target through which pathogens can control the infected environment and evade the immune response. An interesting aspect of the Hh pathway in patients with viral infections is its potential role in immune evasion. In some patients, viruses can hijack Hh signaling to modulate immune responses and enhance their persistence within the host [25,97]. Hepatitis, especially hepatitis B and C, is considered an important cause of cirrhosis and HCC [23]. A study of patients with viral hepatitis reported that there was an increase in Shh ligand expression in all the samples analyzed, which in turn resulted in the expansion of cells that respond to the pathway, including activated HSCs, endothelial cells and HPCs. Additionally, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in a hepatocyte cell culture stimulated the production of Hh ligands [23] (Fig. 7). Conversely, the treatment of cultured hepatocytes with the complete hepatitis B virus (HBV) replicon and serum-treated cultures from HCV patients activate signaling pathways and thus profibrotic effects [24].

Hedgehog (Hh) activation in viral infections. The overexpression of the Hh pathway in viral infections is associated mainly with excessive ECM production caused by the activation of HSCs and the accumulation of HPCs, leading to the progression of the disease (cirrhosis and HCC). Administration of a Hh pathway inhibitor decreases damage and prevents progression to more severe forms of the disease.

Cholangiocytes are epithelial cells that line bile ducts and play crucial roles in bile composition and transport. Additionally, they contribute to liver repair by promoting the accumulation of inflammatory and myofibroblastic cells [98,99]. When exposed to harmful conditions, cholangiocytes secrete proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines that regulate their proliferation, apoptosis, and senescence, potentially leading to irreversible pathologies [100,101]. Chronic damage to these cells results in cholangiopathies, a group of diseases characterized by bile duct disruption that can progress to chronic cholestasis, inflammation, fibrosis, and cirrhosis, ultimately leading to end-stage liver disease [98,100].

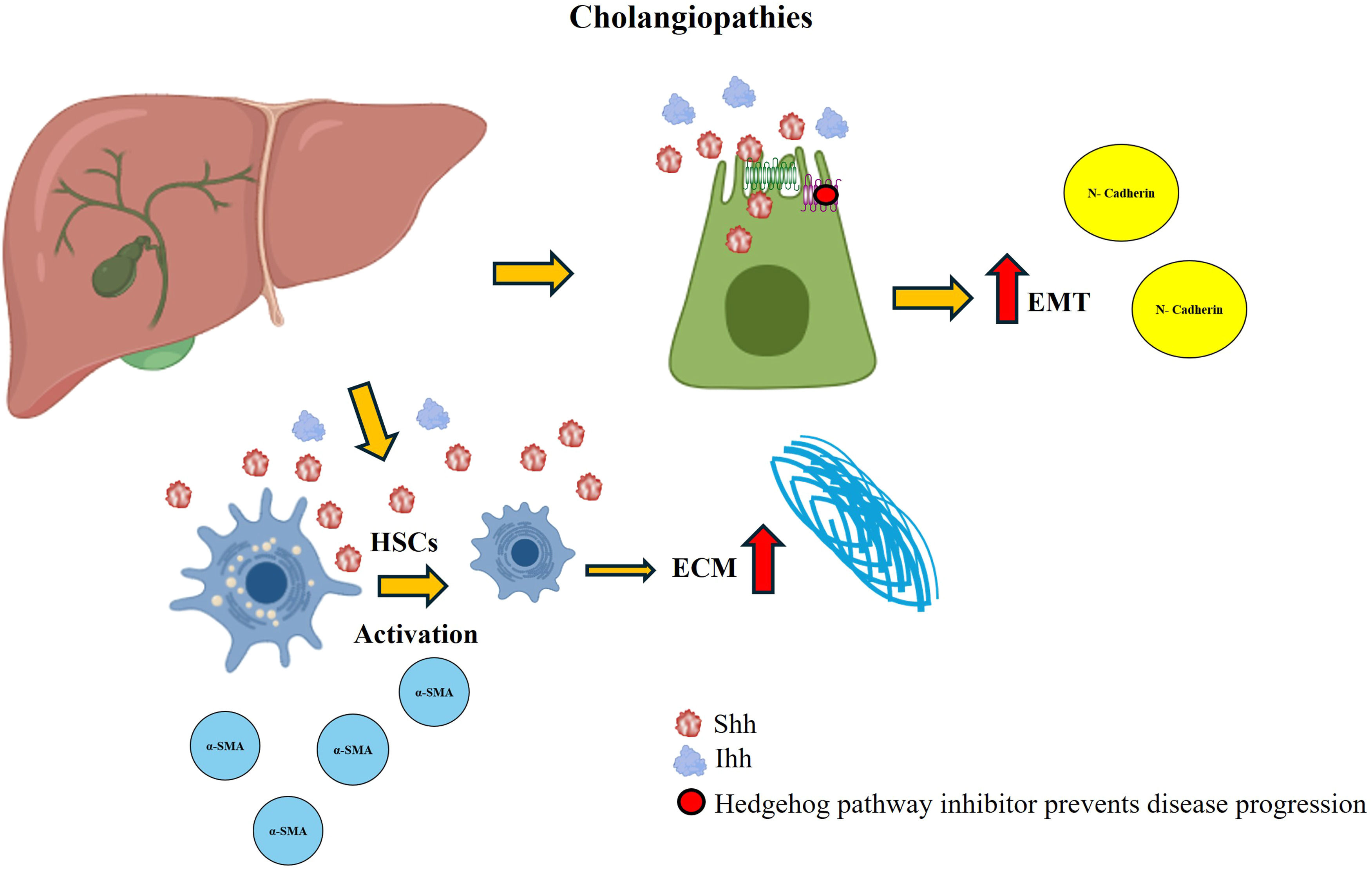

In a rat model of reversible biliary obstruction, the Hh pathway was reported to participate in liver remodeling. The Hh pathway is activated during obstruction and remains in this state even weeks after obstruction removal. As the hepatic architecture recovers, ligand and transcription factor expression decreases [71]. In addition, the administration of platelet-derived growth factor-BB to cholangiocyte cultures increased the expression of Shh ligands [71]. Conversely, the Hh pathway has been shown to play an essential role in EMT in samples from patients with chronic biliary injury and in primary cultures of cholangiocytes isolated from rats that underwent bile duct ligation. EMT was observed in Hh-expressing cholangiocytes, and the release of ligation resulted in decreased Hh activity, EMT, and biliary fibrosis (Fig. 8). In a coculture of cholangiocytes with activated HSCs, EMT promotion and cellular migration occur, an effect that neutralizing antibodies can block [102]. Another study model is based on samples from patients with primary biliary cirrhosis in which the expression of molecular components of the Hh pathway (Ihh, Ptc, and Gli) has been detected in portal areas and fibroblastic stromal cells. These findings suggest that activation of the Hh pathway is a key factor in the development of human liver disease [103].

Hedgehog (Hh) activation in cholangiopathies. During the development of cholangiopathies, Shh and Ihh ligands are produced, which favor the activation of HSCs and the irregular production of the ECM. In addition, this activation promotes EMT. These effects are decreased when a pathway inhibitor is administered.

The Hh pathway is essential for proper embryonic development; however, its dysregulation has been linked to the adult onset of several types of cancers [26]. Aberrant activation of this pathway contributes to tumor initiation and maintenance in patients with malignancies such as basal cell carcinoma, medulloblastoma, small cell lung cancer, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma, in which the highly activated Hh pathway is sufficient to promote both tumorigenesis and cell survival [104]. In the liver, abnormal Hh pathway activity has been associated with the development of hepatoblastoma, HCC, and cholangiocarcinoma [105].

There are three fundamental means by which the Hh pathway can be activated in cancer: autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine mechanisms. The autocrine mechanisms are attributed to ligand-independent activation, typically caused by mutations that inactivate negative modulators of the pathway, leading to their constitutive activation [106,107]. The paracrine mechanisms refer to ligand-dependent activation, in which cancer cells produce and secrete Shh ligands, thereby stimulating adjacent cells [106]. The endocrine mechanism is also ligand-dependent but involves the activation of stromal cells in response to ligand production by cancer cells. Additionally, a reverse paracrine mechanism in which stromal cells produce Shh ligands that, in turn, activate cancer cells has been identified [106,107].

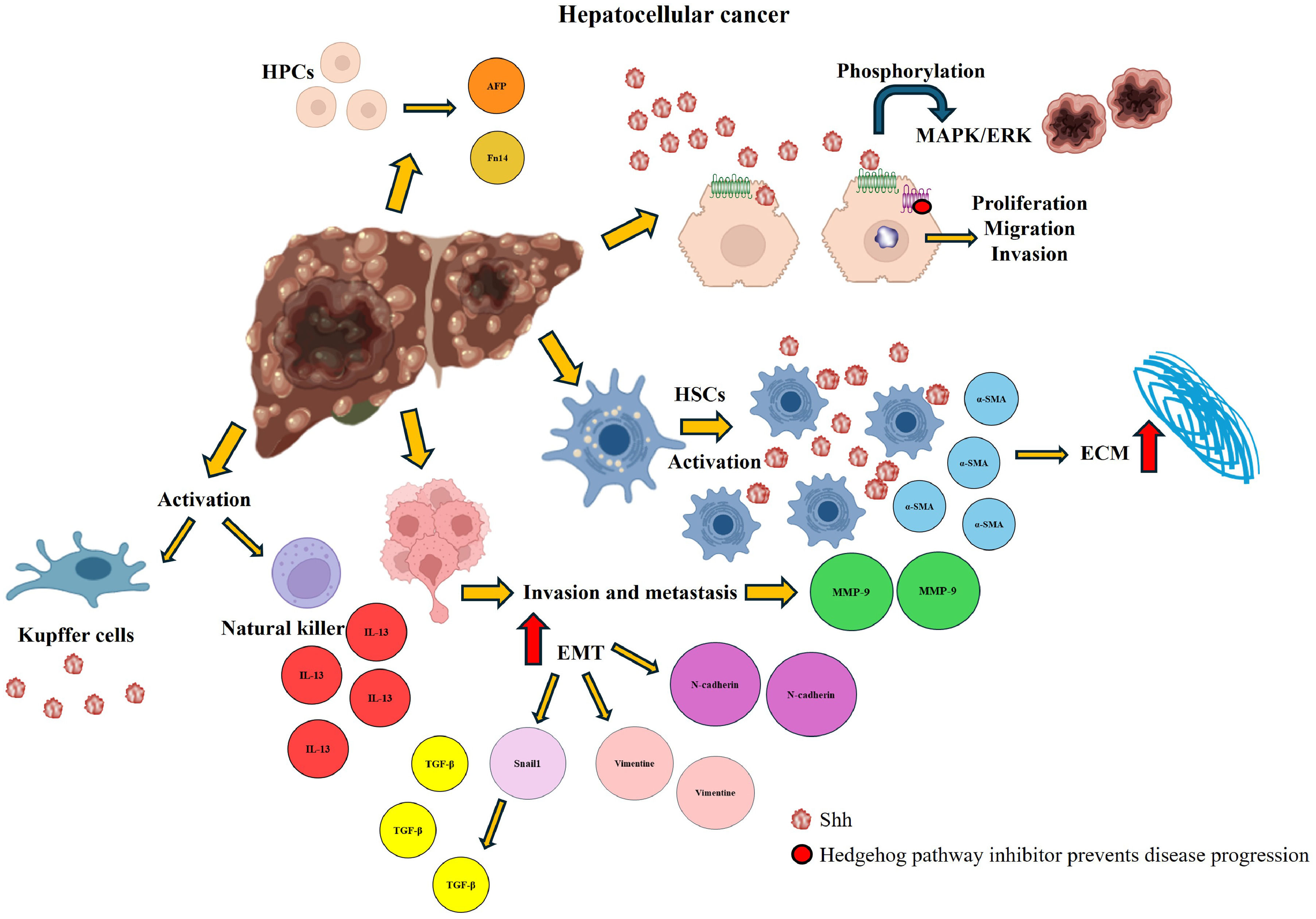

In the liver, aberrant Hh pathway activation is frequently observed in patients with HCC, where it promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [108]. This dysregulated activation is driven primarily by mutations in key components of the pathway [109]. HCC is one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality worldwide, arising from various etiological factors that induce molecular and cellular alterations in the liver [110]. Its development is considered a multistep process in which chronic inflammation, necrosis, cellular regeneration, and fibrosis play pivotal roles [111]. Treatment options for HCC are highly dependent on tumor stage and hepatic function. Surgical resection and liver transplantation are the most effective strategies for early-stage HCC, whereas systemic therapy is recommended for advanced-stage HCC [110,111].

Hh ligands are produced primarily by damaged hepatocytes, activated HSCs, endothelial cells, and immune cells [27]. The presence of Shh ligands in HCC patient samples has been correlated with tumor progression, as expression of key components of this pathway is consistently detected in tumor tissues [112]. Specifically, expression of the Shh ligand has been identified in both the tumor niche and adjacent tissue, whereas Gli1 and Ptc are exclusively expressed in the tumor microenvironment but not in surrounding liver tissue [108,113]. Additionally, the Hh pathway has been shown to influence MAPK/ERK phosphorylation, thereby promoting tumor formation [108]. The Hh pathway is also involved in HCC invasion and metastasis, primarily through the upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) expression. The inhibition of MMP-9 expression has been linked to a decrease in cell migration and invasion, as well as a reduction in ERK1/2 protein expression [114] (Fig. 9).

Hedgehog (Hh) activation in hepatocellular carcinoma. The overexpression of the Hh pathway in HCC is associated with the activation of ECM production via activation of HSCs. It favors the accumulation of HPCs, cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, as well as increases the expression of markers involved in EMT. In addition, other signaling pathways involved in tumor development are activated. Administration of a pathway inhibitor reverses the damage and prevents its progression.

A defining characteristic of various cancers is EMT, a process that enhances cell motility, disrupts intracellular communication, and facilitates metastasis by enabling cancer cells to detach from the primary tumor [115]. Recent evidence indicates that the Hh pathway contributes to monocyte infiltration in the HCC. In a transwell migration assay, GLI1—the downstream transcriptional effector of the Hh pathway in HCC cells—was shown to enhance the migration of THP-1 monocytes. Among the cytokines regulated by Hh signaling in HCC cells, CCL20 emerged as a key mediator, acting through its receptor CCR6 on THP-1 cells to promote their migration [116].

In patients with HCC, the expression of Gli1, the key transcription factor of the Hh pathway, is strongly correlated with EMT, intrahepatic metastasis, and portal venous invasion. Gli1 expression is significantly upregulated in tumor tissues, a phenomenon attributed to the aberrant production of Shh ligands by cancer cells [112]. Hh pathway activation also plays a crucial role in HSC activation, leading to the transformation of HSCs into myofibroblast-like cells [106]. Moreover, Gli1 directly modulates EMT by upregulating the expression of snail family transcriptional repressor 1, an essential EMT regulator, and functions as an effector of the TGF-β signaling pathway [115]. Another key protein associated with the Hh pathway is Jagged canonical Notch ligand 2 (Jagged2), which has been implicated in multiple malignancies and neoplasms [117,118]. Both Jagged2 and Gli1 are overexpressed in HCC, contributing to tumor invasion and metastasis [119].

7Inhibitors of the Hh pathwayInappropriate activation of the Hh pathway has been associated with various diseases, which has led to the study of multiple inhibitors that could be used as potential therapeutic agents [26]. The most widely used inhibitor across various experimental studies is cyclopamine, which is derived from the plant V. californicum.

In the middle of the 20th century, in Idaho, USA, sheep were born with severe craniofacial defects from mothers who grazed V. californicum during drought periods. Owing to the urgency of the situation, the conditions of the environment in which these ewes developed were evaluated, and it was discovered that the consumption of this plant caused fetuses to experience craniofacial malformations from the first 14 days of gestation [42,119]. Subsequently, several analyses of the metabolites present in the plant were performed, and it was demonstrated that cyclopamine, a natural steroidal alkaloid, was the main cause of cyclopia and holoprosencephalic fetuses in cattle via blockage of the Hh signaling pathway through its binding to the Smo coreceptor [120].

This alkaloid has strong binding potential to the transmembrane domain of Smo, preventing its conformational change, which inhibits the activation of the signaling cascade [120,121]. Its teratogenic and toxic effects were reported in studies in which in vitro and in vivo tests were performed. In vivo tests showed that a dose of 160 mg/kg cyclopamine causes severe facial defects, including cleft lip and cleft palate in mouse embryos, anomalies that mimic congenital defects in humans, whereas at a dose of 10–50 mg/kg, the Hh pathway is optimally inhibited without causing alterations in the animals [41].

Currently, several synthetic inhibitors targeting the Hh pathway at the level of Smo—including vismodegib, sonidegib, patidegib, and itraconazole—have been developed and approved for the treatment of various cancers in countries such as the United States, Switzerland, and Australia. The clinical use of these agents has been associated with manageable side effects, most commonly muscle spasms, taste disturbances, and alopecia, without causing severe adverse reactions [62,122]. In contrast, cyclopamine, a naturally derived Hh pathway inhibitor, has been studied only in experimental animal models because of its poor oral bioavailability. At high doses, cyclopamine can induce various adverse effects, including weight loss, dehydration, and teratogenic abnormalities [47,123].

Vismodegib was the first drug in this group to become commercially available (January 2012) for the treatment of metastatic or advanced basal cell carcinoma; this drug inhibits Smo by negatively regulating Gli gene expression, leading to tumor suppression [43,124]. Sonidegib, an inhibitor of the same protein, was the second drug to be approved and has been used as a treatment for patients with basal cell carcinoma; it blocks activation of the Hh pathway and causes tumor suppression [43,124]. Itraconazole, an antifungal drug, was recently identified as an anticancer chemotherapeutic that inhibits angiogenesis and the Hh pathway by preventing the translocation of Smo to primary cilia [17,43,125].

8Clinical evidence, biomarkers, and therapeutic strategiesRecent translational and clinical studies increasingly implicate Hh signaling in the pathogenesis of human liver diseases, highlighting its potential both as a biomarker and as a therapeutic target. In MASLD, a cohort study involving 90 patients demonstrated that hepatic activation of the Hh pathway—assessed by immunohistochemistry for Hh ligand–expressing and responsive cells—was significantly correlated with fibrosis stage, hepatocellular ballooning, portal inflammation, and other histological markers of disease severity. Furthermore, clinical features commonly associated with metabolic syndrome, including age, body mass index, waist circumference, insulin resistance, and hypertension, were also linked to increased Hh activity [85]. Similarly, in HCC, a cohort of 1360 patients revealed elevated expression of Shh protein and mRNA, findings that were associated with poorer prognosis and suggested that this pathway may represent a promising therapeutic target in HCC [112]. More recently, circulating Ihh has been proposed as a mechanism-based, non-invasive biomarker for MASH, as serum levels were significantly elevated in patients with steatohepatitis and fibrosis compared with those with simple steatosis. Supporting this observation, animal studies showed that hepatocyte-specific silencing of TAZ reduced both hepatic fibrosis and circulating Ihh levels, reinforcing its potential clinical utility [126].

Pharmacological inhibition of the Hh pathway has also shown encouraging results in clinical trials, although its application in liver disease remains limited. Vismodegib (GDC-0449), an orally available Smo inhibitor, has demonstrated the greatest clinical progress to date. Initial studies in patients with basal cell carcinoma and medulloblastoma established both significant efficacy and a favorable safety profile [127]. Alongside vismodegib, sonidegib, another Smo inhibitor, is also approved for basal cell carcinoma and has demonstrated antitumor activity in other malignancies. Clinical trials in advanced basal cell carcinoma reported objective response rates of approximately 30–40 %, with evidence of Hh pathway suppression confirmed by decreased GLI expression in tumor tissues [128]. Nevertheless, the translation of Hh inhibition into fibrotic and metabolic liver diseases is still in its early stages. For instance, a phase II trial evaluating vismodegib in combination with chemotherapy for metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma demonstrated acceptable safety and some clinical responses but did not significantly improve progression-free survival compared with chemotherapy alone, underscoring the challenges of applying Hh inhibition in contexts where the pathway is not the primary oncogenic driver [129].

Preclinical evidence further supports this therapeutic rationale. In experimental models of MASH and liver fibrosis, pharmacological inhibition of Smo consistently demonstrated antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects, thereby providing a strong foundation for future clinical studies of Hh pathway modulation in chronic liver disease [130]. However, despite these promising insights, substantial gaps remain. One of the main challenges lies in patient stratification, as Hh activation levels vary by etiology and disease stage; thus, identifying subgroups with high pathway activity may be critical for maximizing therapeutic benefit. In addition, the long-term safety and tolerability of Hh inhibitors in patients with chronic liver disease remain uncertain, given their established side-effect profiles. Addressing these issues will be essential for advancing Hh-targeted strategies from experimental models into routine clinical practice.

9ConclusionsThe Hh pathway plays a fundamental role in liver development, homeostasis, and regeneration by regulating progenitor cell differentiation, bile duct and vascular formation, and metabolic balance. While the physiological activity of this pathway supports liver integrity, its dysregulation is strongly linked to fibrosis, cholestatic disorders, metabolic dysfunction, and hepatocellular carcinoma. This dual role makes Hh signaling an attractive therapeutic target. The identification of new modulators, particularly natural compounds from plants, fungi, or microorganisms, offers promising and potentially safe alternatives for early intervention, as they may restore the balance between regeneration and fibrogenesis without disrupting liver homeostasis. Furthermore, increasing evidence supports the role of Hh signaling in liver cancer progression, underlining its potential as both a diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target. However, additional studies are required to better clarify its molecular interactions and optimize the development of effective therapies, which are especially relevant given the growing global burden of chronic liver diseases.

CRediT authorship contribution statementKarla Jocelyn Ortega-Carballo: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Eduardo Enrique Vargas-Pozada: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Pablo Muriel: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

None.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.