Hepatic arterioportal fistula (HAPF) is an abnormal communication between the hepatic arterial and venous systems. Intrahepatic HAPFs may be congenital, or, more frequently, acquired. The latter being possibly spontaneous, mainly associated with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), liver benign neoplasms or liver vascular malformations, or caused by a local trauma (blunt trauma, liver biopsy, liver surgery, and transhepatic drainage or shunt); a non negligeable proportion are idiopathic [1]. Technological progress and the increasing number of performed radiological exams helped to increase HAPFs detection rate [2]. In HAPFs, arterial blood flows from the hepatic artery system directly into the portal tract, thus possibly leading to portal hypertension (PH). Clinical presentation is largely dependent on the size, location and volume of the fistula, and it may range from asymptomatic to impairment of liver function and clinical features of PH (ascites and gastrointestinal bleeding) [1]. Intrahepatic color speckling with mosaic pattern combined with dilated portal vein with arterial waveforms is the most typical Doppler-ultrasound (US) sign of a HAPF [3]. Asymptomatic HAPFs should be kept on follow-up, while symptomatic cases should be actively addressed. Endovascular embolization [1] has emerged as the therapeutic gold-standard.

2Patients and MethodsWe report the first case of a post-biopsy HAPF causing PH in a patient affected from non-advanced primary biliary cholangitis (PBC). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient included in the study, and the study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the institution's human research committee.

In November 2023, a 26-years-old female presented at our Center for Autoimmune Liver Diseases as an outpatient for a second opinion regarding her biliopathy. In 2017 she was diagnosed with PBC in another Center through a US-assisted right-lobe liver biopsy, showing the pathognomonic features of vanishing of septal bile duct and presence of lymphocytic cholangitis, portal and periportal microgranulomas. No fibrotic septa were revealed, configuring a fibrosis stage 0 sec. Nakanuma-Hitamatsu. At diagnosis, liver stiffness measured through FibroScan® excluded an advanced fibrotic disease (stiffness 7.7 kPa, IQR 1.3, 18 %); furthermore, no radiological signs of PH were revealed at abdominal US. No other comorbidities were reported in the patient’s medical history. The patient was treated with 15 mg/Kg ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA).

In October 2023, the patient reported a single episode of melena; at laboratory examinations, pancytopenia with severe anemia was revealed [hemoglobin – Hb 6 g/dL, white blood cells (WBC) 2860/mm3, platelets (PLT) 128.000/mm3]; serum transaminase levels were normal, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) were stably at twice/three times the upper limit of normal (ULN); prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times were normal. Liver stiffness worsened reaching 11.9 kPa, IQR 1.5, 11 %. She was thus referred to our center: the esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGDS) revealed the presence of high-risk blue varices with red marks and mild congestive antral gastropathy.

Serology for HBV, HCV, HIV CMV, EBV and Parvovirus was negative. The autoimmune antibodies panel revealed a positivity for anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASMA) and anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMA) AMA-M2 and AMA M23E. Levels of immunoglobulins (IgG) were elevated, while IgMs and IgAs levels were normal.

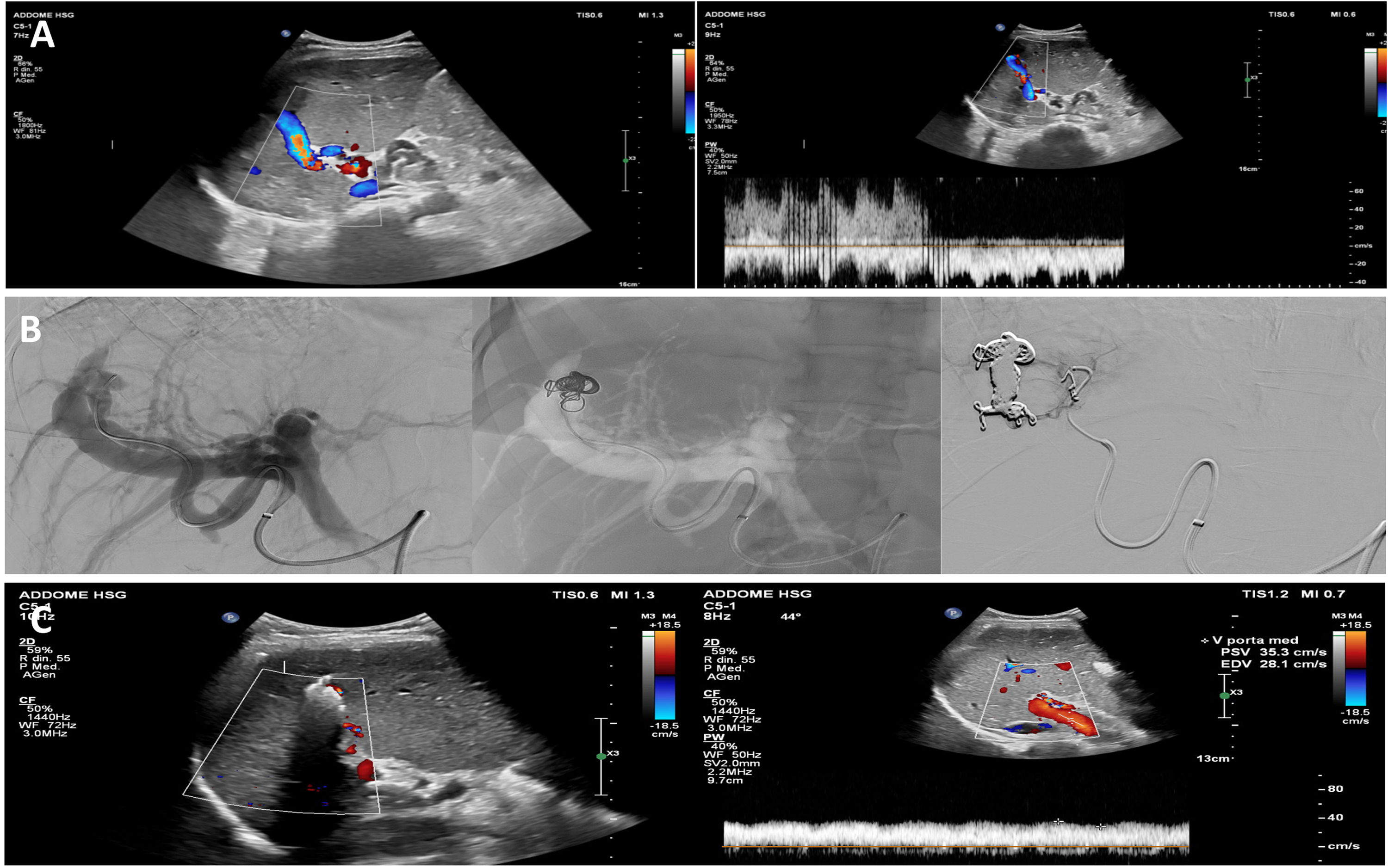

Abdominal contrast-enhanced (CE) computed tomography (CT) showed moderate hepatosplenomegaly with smooth and regular liver margins; an hyperenhanced vascular lesion in the context of the sixth segment was detected and the porto-splenic axis was dilated (portal and splenic vein of 12 mm and 14 mm, respectively) with an early and prolonged enhancement during arterial phase; these findings were diagnostic for a liver fistula. Numerous periportal, periesophageal and spleno-renal collateral circles were detected, in the absence of splanchnic veins thrombosis and ascites. Hepatic Doppler-US confirmed a high-flow HAPF between the right hepatic artery and right portal vein, causing arterialization and reversal of portal flow (Fig. 1, panel A).

A) Doppler-US appearance of a turbulent high-flow vascular lesion in the context of the right hepatic lobe with evidence of periportal liver hilar collaterals and reversal of portal blood flow. B) Angiography appearance of selective spring steel coils embolization of the fistula. C) US appearance of the spring steel coils embolization of HAPF, with no Doppler-US residual blood flow.

We interpreted the vascular alteration as a post-liver biopsy HAPF, based on the localization of the HAPF and its absence at pre-biopsy abdominal US, the early stage and the stability of PBC, and the absence of radiological signs of cirrhosis. We attributed to HAPF’s high flow the most remarkable proportion of PH, therefore the patient was started with non-selective beta-blocker (Carvedilol 6.25 mg bid) and referred to the Interventional Radiology Department for HAPF embolization (Fig. 1, panel B): controlled-release spring steel coils (one 12 mm x 60 mm Ruby coil, two 60 mm and 45 mm Packing coils, one 18 mm x 40 mm Concerto coil, and one 3mm Concerto coil) and 1:2 Glubran + Lipiodol solution were placed in the fistula. No residual HAPF was observed at last arteriography.

2.1Ethical statementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient included in the study, and the study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the institution's human research committee.

3ResultsOne-week abdominal CE-CT scan confirmed HAPF obliteration, and re-evaluation EGDS showed significant improvement: blue low-risk esophageal varices with no red marks and mild congestive antral gastropathy were revealed. Given the clinical stability, the patient was discharged with the indication to continue the carvedilol treatment.

At one-month follow-up, liver Doppler-US confirmed the absence of blood flow in the treated HAPF, a normodirected hepatopetal flow in the main portal trunk (Fig. 1, panel C) and a reduced splenomegaly (bipolar splenic diameter 16 cm). Laboratory examinations showed a regression of pancytopenia and a mild improvement of liver function tests (Hb 12.1 g/dL, WBC 5120/mm3, PLT 140.000/mm3, ALT 77 U/L, AST 60 U/L, ALP 177 U/L, GGT 104 U/L, Bilirubin 0.99 mg/dL). Carvedilol has been discontinued and the patient was kept on clinical, biochemical, and radiological follow-up. We reserved for future follow-up visits the possibility of an upgrade to II-line therapeutic strategy for PBC in case liver function laboratory examinations failed to normalize.

4DiscussionWe performed a systematic research in PubMed, Medline and Embase databases for case reports and case series using the terms ‘hepatic arterioportal fistula’, ‘post-biopsy hepatic fistula’, and ‘hepatic fistula AND PBC’, and evaluated those with an English written abstract available [1,2,4–9] (Table 1).

PubMed, Medline and Embase published cases of HAPFs.

| Study | Year of publication | Study type | Number of reported cases | HAPF etiology | Clinical manifestation (yes/no) | Embolizing technique and agents | Technical success* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 2022 | Retrospective | 97 | - HCC 80 %- Cirrhosis 10 %- Congenital 2 %- Liver trauma 1 %- Unclear 2 % | Yes (100 %) | Endovascular:- PVA- lipiodol + gelatin sponge- spring steel coils (proportion non specified) | Yes in 100 % of the cases (81 % with effective clinical closure) |

| 24 | 2004 | Retrospective | 97 | HCC (100 %) | NA (not all of them but no proportion specified) | Endovascular:- 64 ethanol- 33 gelfoam | Yes in 100 % of the cases (higher complete occlusion rate, lower recanalization rate and better survival in the ethanol group) |

| 32 | 2012 | Case series | 4 | - 2 iatrogenic(1 post biliary drainage, 1 post-biopsy)- 2 post-traumatic(1 after car accident, 1 after blunt trauma) | Yes (100 %) | Endovascular:- 1 NBCA Glue- 3 spring steel coils | Yes in 100 % of the cases |

| 45 | 2023 | Case report | 1 | Congenital | Yes | Direct trans-hepatic US guided coils placement | Yes |

| 56 | 2023 | Case report | 1 | Not specifically reported (congenital?) | Yes | Endovascular spring steel coils placement | Yes |

| 67 | 2022 | Case report | 1 | Post-traumatic | Yes | Endovascular coated stent placement | Yes |

| 78 | 2023 | Case report | 1 | Spontaneous (EHPVO-related) | Yes | Combined endovascular coils placement and surgical splenorenal shunt creation | Yes |

| 89 | 2018 | Case report | 1 | Post-traumatic | Yes | Endovascular coils embolization | Yes |

Post-biopsy HAPF was firstly described by Preger in 1967 [10] as an iatrogenic abnormal direct communication between the peripheric hepatic arterial and portal venous systems which occurs in proximity and along with the biliary tract traumatized during liver biopsy. According to an old Swedish series [11], HAPFs can be detected in up to 50 % of the cases during the first week after liver biopsy, while their prevalence decreases to 10 % of the cases after two weeks from the procedure. Okuda et al., confirmed this trend demonstrating that only 5 % of the patients undergoing liver biopsy show a vascular fistula at one-month follow-up angiography [12]. Overall, post-biopsy HAPFs represent less than 1 % of all liver vascular fistulas. To the best of our knowledge, no cases of hepatic fistulas have ever been described in PBC, and moreover no post-liver-biopsy for PBC diagnosis HAPFs have ever been reported.

Only a minority of permanent fistulas are symptomatic, and the presentation depends on etiology, size, and flow through the shunt. Haemobilia and manifestations of PH are the most common signs, while unusual manifestation can be mesenteric vascular congestion with consequent abdominal pain and/or diarrhea. Long-term persistence may lead to hepatoportal sclerosis and portal fibrosis [2].

With reference to our case, we attributed most of the clinical manifestations of PH to the detected high-flow post-biopsy HAPF although PBC may present clinically significant PH even at early-histologic-disease stages [13] which is a rare scenario, usually accompanied by typical histologic lesions and lack of response to UDCA treatment [14].

Diagnostic and follow-up gold standard imaging technique is represented by the digital subtraction angiography but, as highlighted in our case report, Doppler-US, abdominal CE-CT scan or CE-Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are usually characterized by a high diagnostic accuracy [1].

The only scenario in which the treatment of the fistula is urgent is in case of haemobilia, otherwise therapeutic management can be electively planned. To help choose the best therapeutic strategy, Guzman et al. proposed a simple classification of HAPFs based on their location, etiology, and flow magnitude. Guzman’s type I HAPFs are usually peripheral and asymptomatic, and they represent the most common HAPFs type after liver biopsy; endovascular embolization is suggested in case of symptomatic or persistent fistula at follow-up. Larger central acquired fistulas are classified as type II HAPFs; they manifest with signs of PH and therefore their embolization is mandatory; surgery is indicated in case of unfeasibility or failure of endovascular treatment, or in case of concomitant need of etiology treatment (es. trauma or HCC resection). Lastly, type III HAPFs are represented by congenital fistulas: these cases should be addressed after a multidisciplinary discussion, involving mainly interventional radiologists, vascular and hepatobiliary surgeons and hepatologists [15]. Endovascular embolization nowadays represents the therapeutic standard of care, and it can be performed with various embolic agents. Currently, most comparative studies among embolizing agents have been performed in HCC-related liver fistulas [4] and yet no consensus but, being long-term resistant agents, spring steel coils are usually applied to high-flow HAPFs, while liquid embolic agents are used in case of multiple small shunts in the same vascular lesion [2]. In any case, therapeutic intervention is the more effective the more it achieves selective fistula closure with preservation of the adjacent normal vasculature.

5ConclusionsIn conclusion, we report the first case of a high-flow post-biopsy HAPF in PBC causing clinically significant PH and PH-related bleeding. Selective embolization of the fistula using both steel coils and liquid embolizing agents has shown to reduce PH and its related complications safely and effectively. We cannot exclude that the clinical manifestations of PH could not have been related also to the PBC itself but, given the temporal correlation with the liver biopsy, the rarity of PH in early-stage PBC, and the improvement of these same PH-related signs after the HAPF embolization, we can affirm that prioritizing the treatment of the fistula has proven impact in the therapeutic management of the patient. A second biopsy, distal to the treated HAPF area, would have been useful to document the the PBC-related quote of PH. Further reports regarding more numerous series are needed to better understand the clinical course of these scenarios and thus to better standardize their management.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributionsG.C. data curation; investigation; writing. I.P. conceptualization; supervision; review and editing.

None.